A complex number comes in pairs: $a + bi$, where $a$ and $b$ are real numbers and $i$ is the square root of negative one.

The magnitude is

$$|z| = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}$$Given the magnitude and an angle $\theta$, you can reconstruct the number:

$$z = |z|(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)$$These numbers are two-dimensional, like fractions — defined by two pieces of information. They live on a plane: the horizontal axis for the real part, the vertical axis for the imaginary. Every complex number is a point; every point is a complex number.

Multiply a complex number by a real scalar — say, $7 \times (2 + 3i) = 14 + 21i$ — and the magnitude changes. The number stretches or shrinks along its direction.

But put $i$ in the exponent, and something else happens:

- Raise a number to the power of $i$, and it rotates.

- $i$ itself rotates $\frac{\pi}{2}$.

- Multiply by $i$ twice — that's $i^2 = -1$ — and you've rotated a full $\pi$.

- Three times, $\frac{3\pi}{2}$.

- Four times, back to where you started: a complete circle.

It doesn't have to be $i \times i$; it can be $e^{i\pi}$ or $3^{2i}$. For some mysterious reason, when $i$ appears in the exponent, the number rotates.

This is what the textbooks teach. This is what earns students high marks.

And yet: why does the exponent rotate? Who decided $\sqrt{-1}$ belongs on a vertical axis? What does the exponential function — the function of growth and decay — have to do with circles?

This wasn't one genius with a complete vision. It was a relay race across three centuries.

The race begins in 1572, when an Italian mathematician named Rafael Bombelli defined the arithmetic rules that make $i$ behave the way it does. He built the engine.

In 1748, Leonhard Euler fed that engine into his infinite series — what we now call the Taylor expansion of $e^x$ — and discovered that growth and oscillation were the same thing in disguise.

And between 1799 and 1831, three men — a Norwegian surveyor, a Parisian bookkeeper, and the prince of mathematicians — finally drew the picture. They gave $i$ a home.

The progression was: arithmetic rules, then analytic connection, then geometric meaning.

To understand why imaginary exponents rotate, we have to trace this path from the beginning.

1572: The Engine

Before Bombelli, mathematicians had stumbled upon $\sqrt{-1}$ while solving cubic equations, and they were scared of it. Gerolamo Cardano, who published the general solution to the cubic in 1545, called these quantities "sophistic" and "as subtle as they are useless." They seemed to break mathematics.

Bombelli was the one who said: What if we stop treating these as errors, and start treating them as numbers with their own rules?

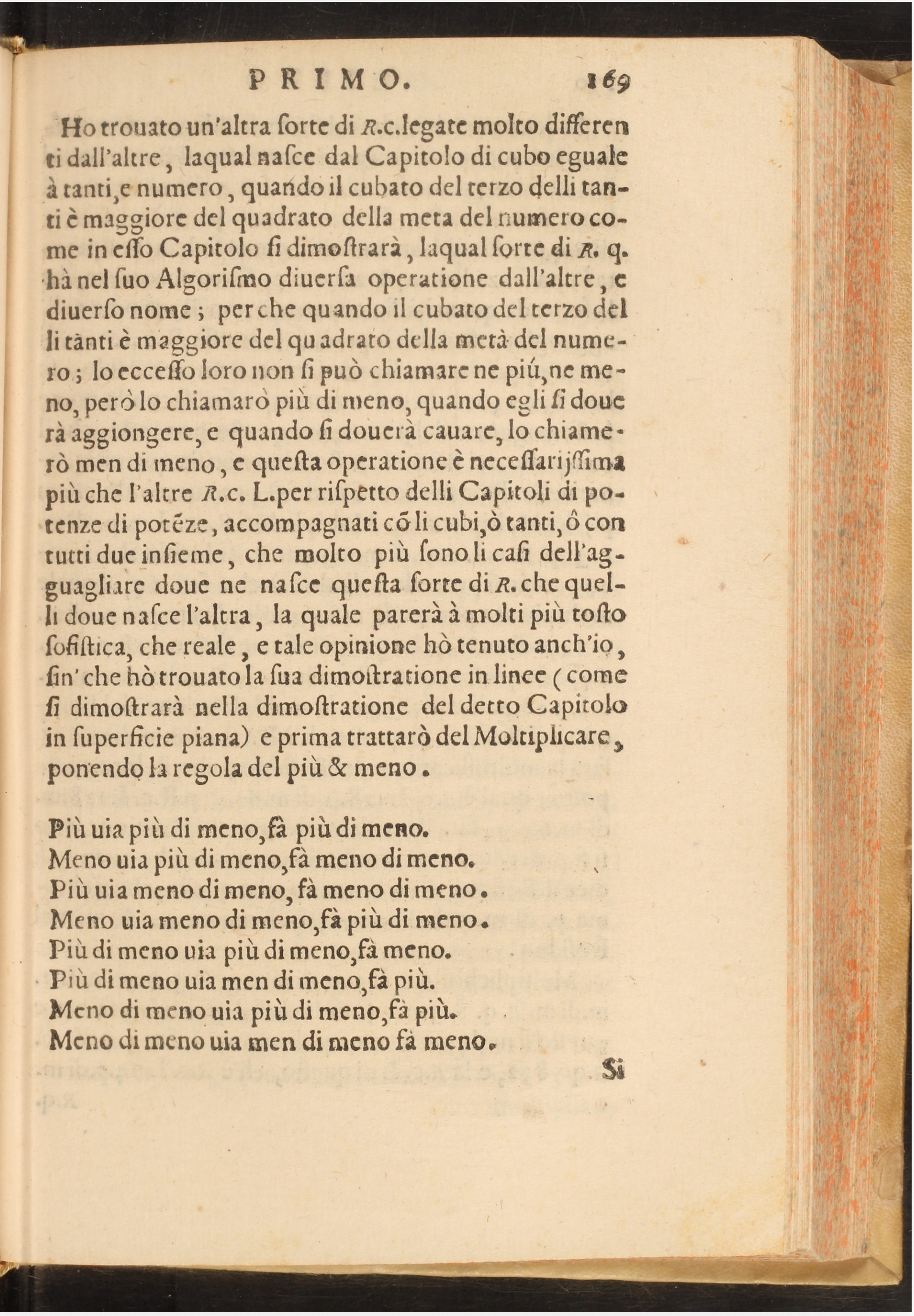

The Discovery: Page 169

In his 1572 masterpiece, L'Algebra, we find the exact moment this engine was switched on. On Page 169, Bombelli writes a hesitation, an apology to the reader:

Courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology

"la quale parerà à molti più tosto sofistica, che reale..."

(...which will seem to many more 'sophistic' [fake/tricky] than real...)

He knew it looked crazy. But he proceeded anyway, defining the multiplication rules in a list that reads almost like a poem. He didn't use the symbol $i$ yet; instead, he used:

- più di meno ("plus of minus") for $+i$

- meno di meno ("minus of minus") for $-i$

Here is the translation of the table he wrote on that page:

Più via più di meno, fa più di meno.

($+1 \times i = i$) — Scaling

Meno via più di meno, fa meno di meno.

($-1 \times i = -i$) — Scaling

Più di meno via più di meno, fa meno.

($i \times i = -1$) — The Rotation!

Più di meno via men di meno, fa più.

($i \times -i = 1$) — Completing the Cycle

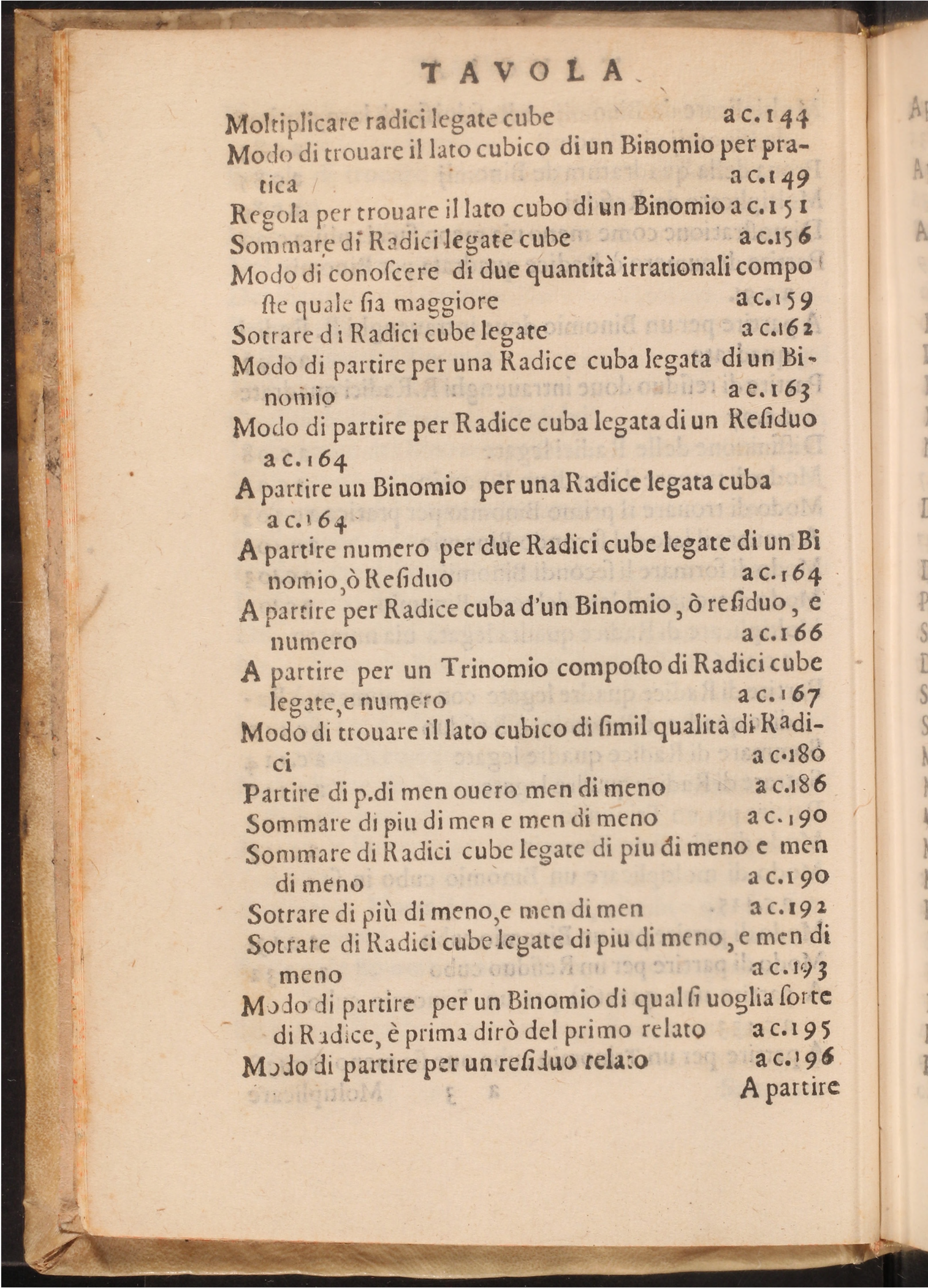

The Context: The Jungle of Roots

To understand the magnitude of Bombelli's achievement, we must look at the environment he was working in. He wasn't just solving one simple equation; he was building an infrastructure to handle an entire class of algebraic monsters.

A Table of Contents entry from this book reveals he was teaching readers how to perform calculations with "linked roots" (nested radicals like $\sqrt[3]{2+\sqrt{-121}}$). Look at the entries for division:

Courtesy of The Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology

"A partire per un Trinomio compoſto di Radici cube legate, e numero"

(To divide by a Trinomial composed of linked cubic roots and a number)

He even has entries for summing "linked cubic roots of plus of minus" (Radici cube legate di più di meno). To survive in this jungle, he needed a robust arithmetic engine. The multiplication cycle ($i \times i = -1$) was his machete.

The Proof: Slaying the Cubic

Now we can watch him use this engine to slay the specific monster that started it all: the cubic equation.

$$x^3 = 15x + 4$$Cardano's formula gave an answer involving the square root of a negative:

$$x = \sqrt[3]{2 + 11i} + \sqrt[3]{2 - 11i}$$This looked impossible. Yet Bombelli knew that $x=4$ was a valid answer ($4^3 = 64$ and $15(4)+4 = 64$). He guessed that the cube roots were themselves complex numbers. He set $\sqrt[3]{2 + 11i} = (a + bi)$.

By applying the rules from Page 169—specifically that Più di meno via più di meno, fa meno ($i^2 = -1$)—he was able to expand the cube:

$$(a + bi)^3 = a^3 + 3a^2(bi) + 3a(bi)^2 + (bi)^3$$ $$= a^3 + 3a^2bi - 3ab^2 - b^3i$$ $$= (a^3 - 3ab^2) + (3a^2b - b^3)i$$He matched the real part to 2 and the imaginary part to 11. Solving this system, he found that $a=2$ and $b=1$. This meant:

$$\sqrt[3]{2 + 11i} = 2 + i$$ $$\sqrt[3]{2 - 11i} = 2 - i$$And then, the magic trick. When he added them together to find $x$, the imaginary parts canceled out perfectly:

$$x = (2 + i) + (2 - i) = 4$$This is why Page 169 exists. Without those multiplication rules, Bombelli couldn't show that the "impossible" math led to the correct real answer. The engine was built because the cubic demanded it.

1748: The Growth Machine

For 176 years, the engine sat there. Mathematicians used it — these "imaginary" numbers kept appearing in calculations, kept giving correct answers — but nobody believed they were real. They were homeless: useful but philosophically embarrassing.

Then came Euler.

1. The Setup: The "DNA" of Functions

Leonhard Euler was the master of infinite series. He realized that functions like $e^x$, $\sin(x)$, and $\cos(x)$ weren't just curves on a graph; they were infinite sums of polynomials. He viewed this as their true "DNA."

He had three definitions sitting on his desk. Two of them came from Isaac Newton, who had discovered decades earlier that the geometry of circles could be written as algebra:

Newton's Cosine Series ($\cos x$):

$$\cos x = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \frac{x^6}{6!} + \dots$$Notice: It uses only even powers ($0, 2, 4\dots$) and the signs alternate.

Newton's Sine Series ($\sin x$):

$$\sin x = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + \dots$$Notice: It uses only odd powers ($1, 3, 5\dots$) and the signs alternate.

But the third definition was Euler's own pride and joy. He had defined the number $e$ (the base of natural logarithms) and its exponential growth series:

Euler's Growth Machine ($e^x$):

$$e^x = 1 + x + \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} + \dots$$Notice: It uses every power, and all signs are positive.

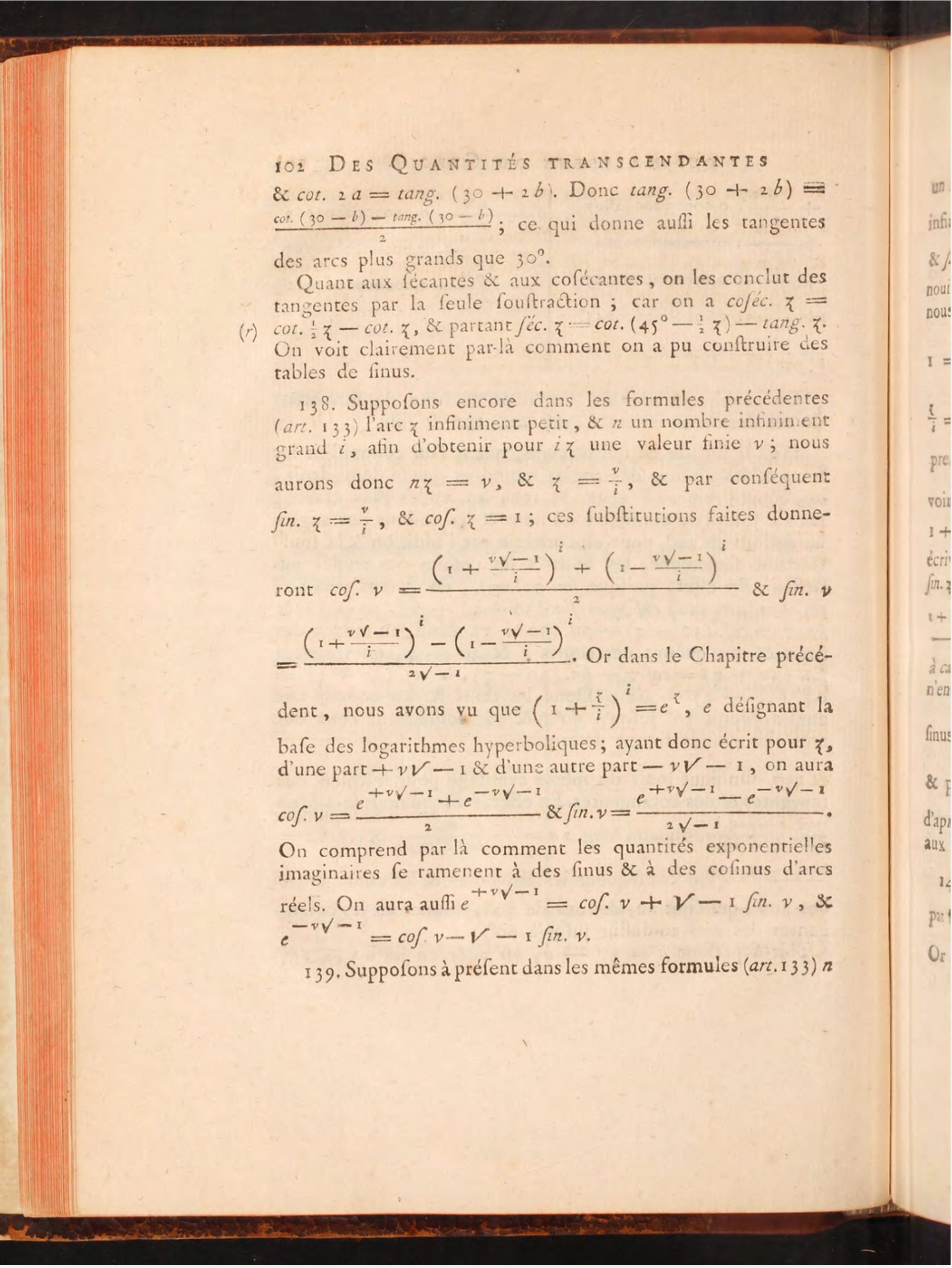

2. The Source: Page 102

In his landmark Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748), Euler performed the alchemy that connected these worlds. We can see the result on Page 102 of this French translation:

Look at the bottom of the page. There it is, in his own hand:

$$e^{+v\sqrt{-1}} = \cos v + \sqrt{-1}\sin v$$He writes out $\sqrt{-1}$ every single time — awkward, but unmistakable. The connection between exponential and trigonometric functions, forced by pure algebra.

3. The "Crunching" (The Alchemy)

How did he get there? Euler asked a fearless question: "What happens if I plug $(ix)$ into my Growth Machine?"

He wasn't trying to draw a circle. He was just manipulating symbols. Let's follow his steps:

$$e^{ix} = 1 + (ix) + \frac{(ix)^2}{2!} + \frac{(ix)^3}{3!} + \frac{(ix)^4}{4!} + \frac{(ix)^5}{5!} + \dots$$Now apply Bombelli's engine — the cycle that $i^2 = -1$, $i^3 = -i$, $i^4 = 1$:

$$e^{ix} = 1 + ix - \frac{x^2}{2!} - \frac{ix^3}{3!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} + \frac{ix^5}{5!} - \dots$$4. The Separation (The Discovery)

Euler looked at this jumbled mess and realized he could sort the terms into two piles: those without $i$ and those with $i$.

Pile 1 (No $i$):

$$1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \dots$$Euler looks at his notes: "Wait, that is exactly Newton's series for Cosine!"

Pile 2 (The $i$ terms):

$$i(x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \dots)$$Euler looks at his notes: "And that is exactly Newton's series for Sine!"

5. The Conclusion

So, purely by trusting the algebra of infinite series, Euler proved:

$$e^{ix} = \text{Pile 1} + \text{Pile 2}$$ $$e^{ix} = \cos(x) + i\sin(x)$$The algebra forced this conclusion. Euler didn't need geometry to see it was true. The cyclic nature of $i$ — the engine Bombelli built — acts as a filter. When you feed $i$ into the exponential function, its four-step cycle breaks the Growth Machine apart, separating the even terms into Cosine and the odd terms into Sine.

The algebra screamed it. The geometric interpretation — the circle — was just the inevitable shadow cast by this algebraic reality.

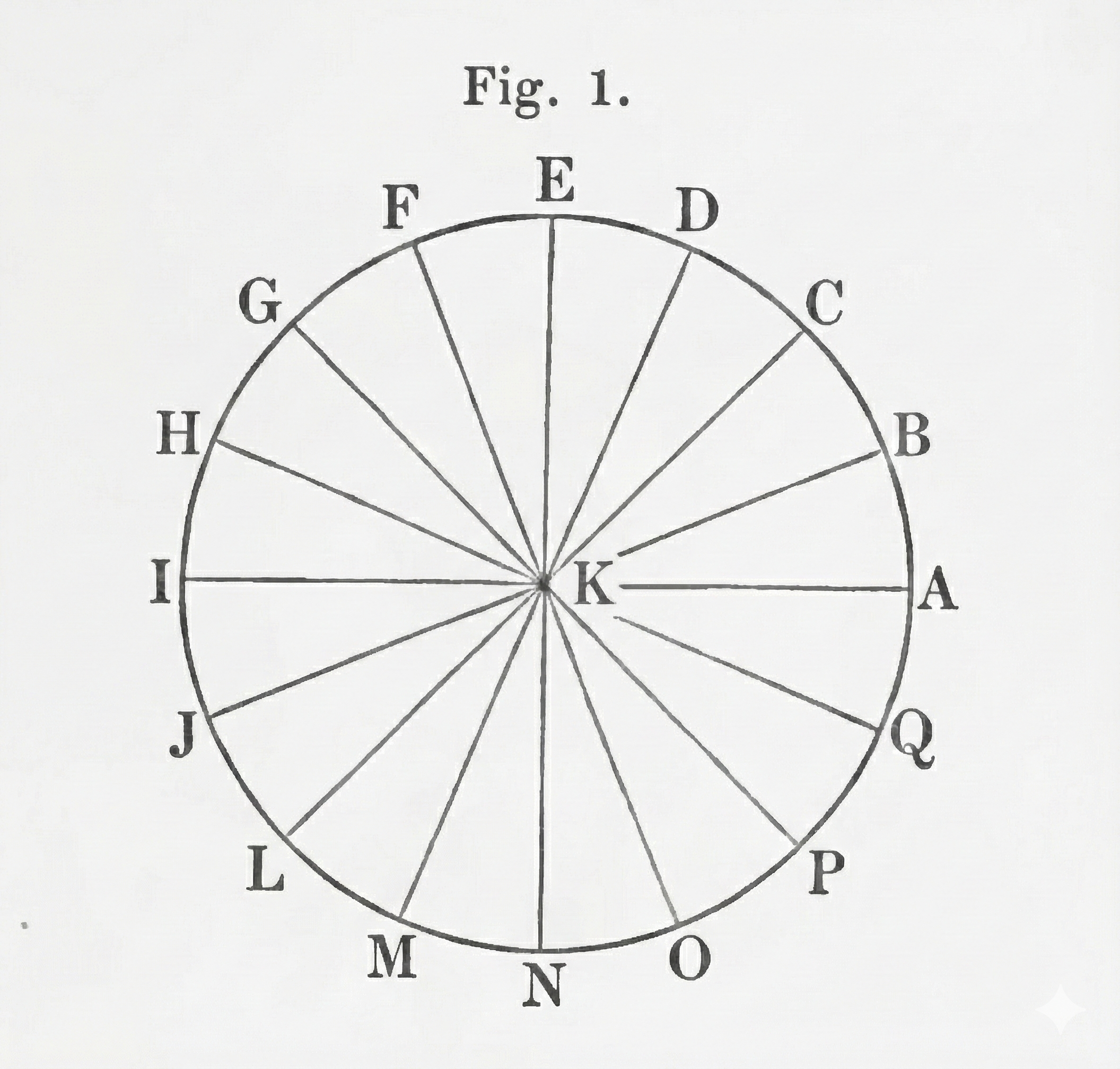

6. The Second Fruit: Dividing the Circle

Euler’s formula didn’t just connect exponential growth to circular motion. It also revealed how the circle divides.

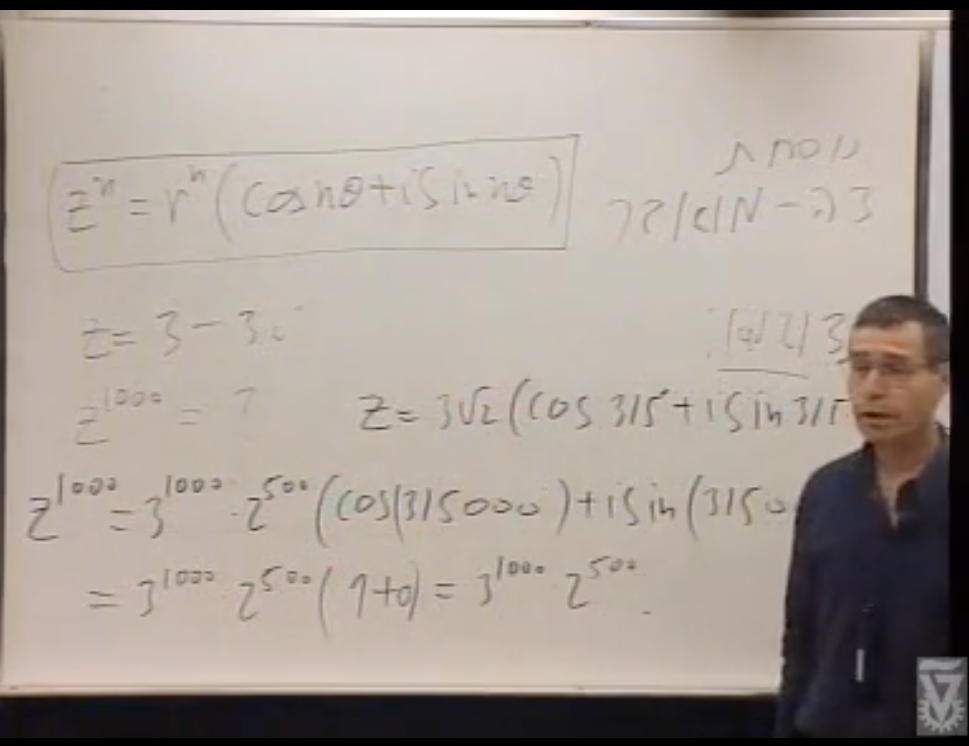

Consider the equation $z^n = 1$. In the real numbers, this is messy ($x^3=1$ has one solution, $x^4=1$ has two). But Euler’s machine offers a constructive solution. It asks: "Which angles, when you rotate by them $n$ times, return you to the start?"

The answer flows directly from the exponent:

$$\zeta_k = e^{i \frac{2\pi k}{n}}$$For $k=0, 1, \dots, n-1$, these are points perfectly spaced around the unit circle. Euler didn't need to "find" these roots; he built them. The Roots of Unity are the direct offspring of his Growth Machine.

Bombelli’s original cycle — $1, i, -1, -i, 1$ — was precisely this logic applied to the case $n=4$. He had discovered the pattern without knowing it was part of an infinite family.

And since a polynomial of degree $n$ can have at most $n$ roots — a basic fact of algebra — these constructed roots must be all of them.

Euler could even prove, using pure series algebra, that these $n$ numbers sum to exactly zero:

$$1 + \zeta + \zeta^2 + \dots + \zeta^{n-1} = \frac{1 - \zeta^n}{1 - \zeta} = \frac{1 - 1}{1 - \zeta} = 0$$Long before the geometric plane was drawn, Euler knew that these numbers formed a perfect, balanced system. He had the symmetry; he was just waiting for the picture.

1799–1831: The Picture

For fifty years after Euler's formula, mathematicians had the equation without the picture.

They could compute $e^{i\pi} = -1$. They knew it was true. But they didn't see it as rotation.

Then, at the turn of the nineteenth century, three men — working largely independently — finally drew the plane.

Caspar Wessel (1799) was a Norwegian surveyor. His job was to calculate coordinates, directions, distances. He realized that if real numbers are a horizontal line, then these "impossible" numbers could be the space off the line — a vertical axis. Multiplication by $i$ wasn't mysterious; it was a quarter-turn.

Jean-Robert Argand (1806) was a Parisian bookkeeper with no formal mathematical training. In 1806, Argand self-published a small pamphlet, within, he drew what no one had dared to draw before: he took the number line (where KA is $+1$ and KI is $-1$) and placed the imaginary numbers perpendicular to it.

Argand reasoned that if multiplying by $-1$ is a 180° turn (from A to I), then multiplying by $\sqrt{-1}$ must be a 90° turn (from A to E). The "homeless" number finally had an address.

The "Dirty Secret"

There is a common whisper among mathematicians that the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra has a "hidden dirty secret."

The accusation goes like this: The theorem promises something about Algebra (polynomials), but it uses tools from Analysis (limits, continuity, smooth curves) to keep that promise. Purists claim this is a betrayal—that to prove the root exists, we had to leave the world of symbols and smuggle in concepts from the world of physics and motion.

But this view misses the deeper history: it ignores the fact that Analysis itself had to pass a rigorous test before it could be trusted. To understand what Gauss truly accomplished, we must look at how mathematics itself evolved in the decades after his proof.

The Re-Engineering of DNA

For centuries, concepts like "the infinite" (calculus) and "the imaginary" (complex numbers) were viewed as dangerous, almost radioactive. They were useful, but unstable. If you handled infinitesimal zeros or square roots of negatives without care, logic decayed into nonsense.

They couldn't become citizens of mathematics until their "DNA" was re-engineered. And the tool that stabilized them was Algebra. We can trace this process through two distinct chronicles:

Chronicle 1: The Limit

- The Radioactive Phase (Newton/Leibniz): They talked about "fluxions" and "infinitesimals." Things that were simultaneously zero and not-zero. It was useful, but it was "amorphous lingo." It felt like magic.

- The Genetic Engineering (Cauchy/Weierstrass): They stripped out the "motion" and the "infinitesimally small."

- The New DNA: $\epsilon$ and $\delta$.

- The Chromosomes: Inequalities ($<$), absolute values ($|x|$), and logical quantifiers ($\forall, \exists$).

- The Result: The limit became purely Algebraic. You could now prove things about calculus using only arithmetic and inequalities. The radioactivity was gone. It was safe to build skyscrapers on it.

Chronicle 2: The Imaginary

- The Radioactive Phase (Cardano/Bombelli): They treated $\sqrt{-1}$ as a "mental torture." It was a ghost that appeared in the middle of a calculation and had to vanish by the end, or the answer was invalid. It was dangerous to touch.

- The Genetic Engineering (Euler/Hamilton):

- Euler's Re-coding: He separated the genes. "Here are the Real terms (Cosine), here are the Imaginary terms (Sine)." He showed they obey the standard Laws of Exponents ($e^{a+b} = e^a e^b$).

- Hamilton's Final Fix: Later, Hamilton defined complex numbers simply as ordered pairs of real numbers $(a, b)$ with a specific multiplication rule. No mystery, no "imaginary" element. Just pairs of numbers and algebraic rules.

- The Result: Complex numbers became just... algebra. The "impossible" $\sqrt{-1}$ was just the operation $(0,1) \times (0,1) = (-1, 0)$.

The Oil Well

This unification goes even deeper. Look at how Richard Dedekind defined "Real" numbers in the 1870s:

- He defined a Real number (like $\sqrt{2}$) as a cut in the Rational number line—splitting all fractions into two sets: those whose square is less than 2, and those whose square is greater.

- He built the "Oil Well" (the deep numbers) entirely out of the "Surface Soil" (the fractions).

- Conclusion: The Reals are not a separate species; they are structurally built from Rationals. It’s all one country.

Imagine living in a country and discovering a vast oil well beneath your feet. You haven't left your territory; you've just realized your territory extends downwards, deep below the surface. The oil well belongs to the country because it is measured by the country's own rulers.

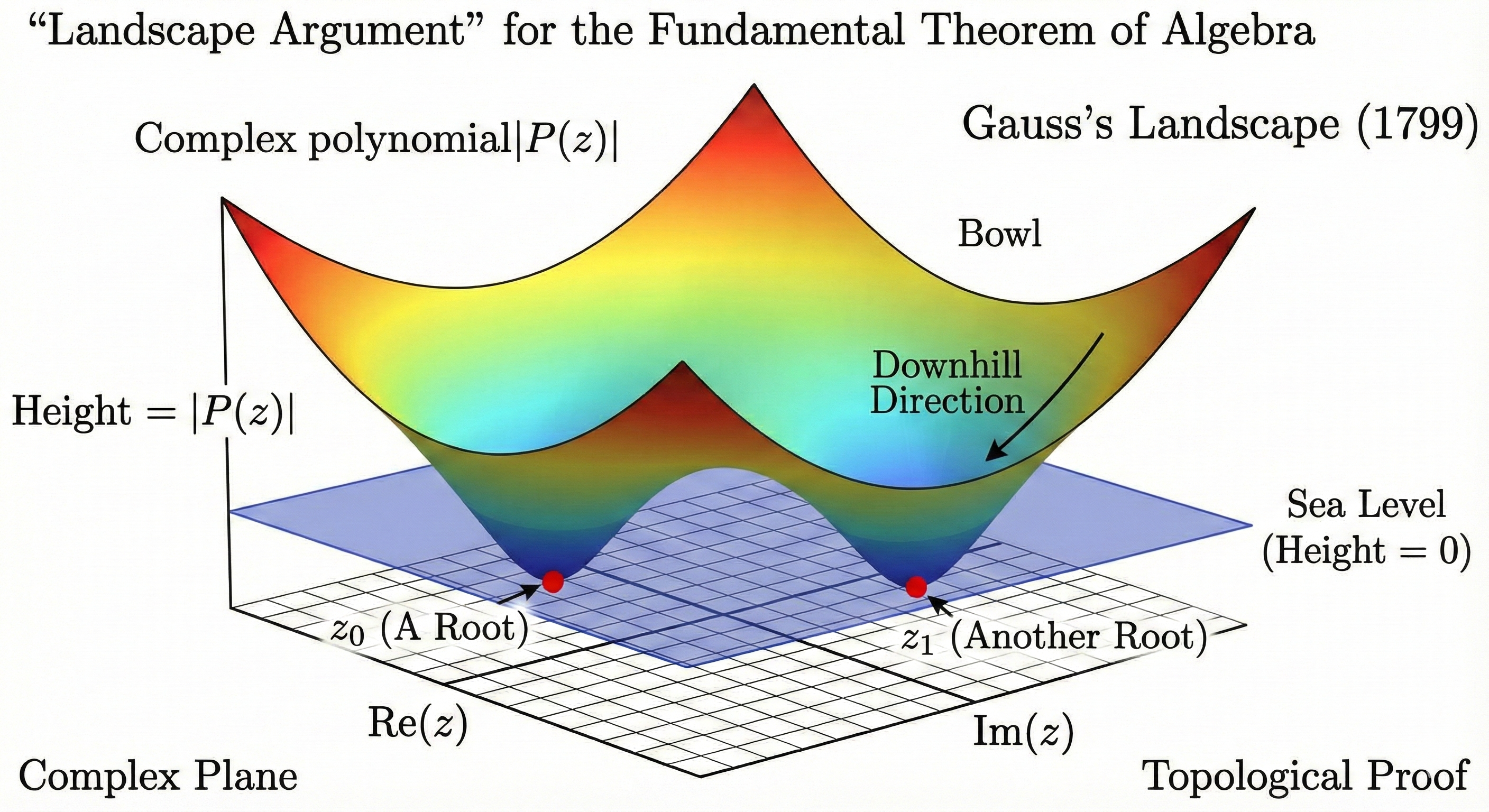

This brings us back to Gauss. His argument works like this: view the magnitude $|P(z)|$ as the height of a landscape. Far from the origin, the height rises to infinity (a bowl), so there must be a lowest point. Gauss showed that at any point above sea level, you can always step downhill. The only way to have a true minimum is if the height is zero—a root.

The Landscape Argument isn't a cheat. It is the realization that the algebraic equation creates the landscape. The symbols $P(z)$ contain the geometric DNA that forces the surface to be smooth, continuous, and bowl-shaped.

When Gauss proved the theorem, he wasn't patching a hole in algebra. He was showing that if you follow the algebraic code to its ultimate conclusion, it builds a structure that must, by necessity of its own geometry, touch the ground.

Euler built the perfect roots. Gauss proved the landscape they live in. Together, they revealed that Algebra and Analysis aren't separate worlds. They are just different depths of the same map.

What It All Means

Start with a number on the real line. Multiply by $-1$, and you flip it: a rotation of $\pi$, a half-turn.

Now ask: is there a number that, multiplied twice, gives $-1$? A "half-flip"?

If flipping is $\pi$, then half a flip is $\frac{\pi}{2}$. The square root of $-1$ isn't a mystery — it's a quarter-turn. It has to live off the line, perpendicular to it.

The cycle Bombelli defined — $1, i, -1, -i, 1$ — is the same as the cycle of quarter-turns around a circle. He encoded rotation 176 years before anyone drew the picture.

Euler's formula says that $e^{i\theta}$ traces the unit circle as $\theta$ varies. Plug in $\theta = \pi$:

$$e^{i\pi} = \cos(\pi) + i\sin(\pi) = -1 + 0i = -1$$The growth constant, the imaginary unit, the ratio of circumference to diameter, and negative unity — bound together because the exponential, when fed imaginary numbers, is circular motion.

Why does $e$ produce circles? Because its Taylor series contains both sine and cosine, interleaved and hidden. The cyclic powers of $i$ act as a filter, separating what was always there.

Three centuries. Three stages.

1572: Bombelli defines the arithmetic. He builds the engine without knowing what it will power.

1748: Euler connects the engine to the Growth Machine. The algebra reveals that exponential and trigonometric functions are the same object, seen from different angles.

1799–1831: Wessel, Argand, and Gauss draw the plane. The homeless number finds a home.

Arithmetic rules. Analytic connection. Geometric meaning.

And a number that turned sideways, and changed everything.

Sources

Argand, Jean-Robert. Essai sur une manière de représenter les quantités imaginaires dans les constructions géométriques. Paris, 1806. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/essaisurunemani00argauoft

Bombelli, Rafael. L'algebra: opera di Rafael Bombelli da Bologna. Bologna: Giovanni Rossi, 1572. Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology. https://catalog.lindahall.org/discovery/delivery/01LINDAHALL_INST:LHL/1287366550005961

Euler, Leonhard. Introduction a l'analyse infinitésimale. Translated by J. B. Labey. Paris: Barrois, 1796. Originally published as Introductio in analysin infinitorum, Lausanne, 1748. Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology. https://catalog.lindahall.org/discovery/delivery/01LINDAHALL_INST:LHL/1287124950005961

This article was written with the assistance of Gemini 3 and Claude Opus 4.5.