yager.io ¶

Available as a blog post or jupyter notebook on Github.

I'm starting a new job at an AI lab soon, working on engineering for RL systems, and I want to do a bit of hands-on NN work to get a sense for what a notebook research workflow might look like, since I imagine a bunch of my coworkers will be using workflows like this.

I've recently been working on some music production plugins, so I have music on my mind. Let's figure out how to train a model to emulate various audio effects, like distortion effects or reverbs. Maybe you have some incredible-sounding guitar pedal that you want a digital simulation of. Can you automatically create such a simulation using machine learning?

I've not read much neural network literature at this point. Basically everything I know about NNs is just from discussions with my friend who works on neural compression codecs. I'll probably do some stupid stuff here, call things by the wrong name, etc., but I find it's often more educational to go in blind and try to figure things out yourself. I'm also only vaguely familiar with pytorch; my mental model is that it's a DAGgy expression evaluator with autodiff. Hopefully that's enough to do something useful here.

I figure an architecture that might work pretty well is to have the previous m input samples, $[i_n, i_{n+1}, ..., i_{n+m-1}, i_{n+m}]$, and the previous m-1 output samples, $[o_n, o_{n+1}, ..., o_{n+m-1}]$, and train the network to generate the next output sample, $o_{n+m}$

[ m prev inputs

| m-1 prev outputs]

|

v

.-------.

| The |

| Model |

'-------'

|

v

[next output]

This architecture seems good to me because:

- It's easy to generate examples of input data where we can train the model 1 sample at a time

- It gives the model enough context to (theoretically) recover information like "what is the current phase of this oscillator"

As for how to actually represent the audio, some initial thoughts:

- You could just pass in and extract straight up $[-1,1]$ float audio into/out of the model

- The model will have to grow hardware to implement a threshold detector ADC or something, which seems kind of wasteful

- This fails to accurately capture entropy density in human audio perception. A signal with peak amplitude 0.01 is often just as clear to humans as a signal with peak amplitude 1.0. Which brings us to a possible improvement

- Pre- and post-process the audio with some sort of compander, like a $\mu$-law

- This will probably help the model maintain perceptual accuracy across wide volume ranges

- Encode a binary representation of the audio. This feels to me like it will probably be difficult for the model to reason about

- Use some sort of one-hot encoding for the amplitude, probably in combination with a companding algorithm. This might be too expensive on the input side (since we have a lot of inputs), but could work well on the output side. We could have 256 different outputs for 8-bit audio, for example

- We could also possibly allow the network to output a continuous "residual" value for adding additional accuracy on top of the one-hot value

For now, let's just try the first thing and see how it goes. I expect it will work OK for well-normalized (loud) audio and poorly for quiet audio.

As for our loss function: probably some sort of perceptual similarity metric would be best, followe by a super simple perceptual-ish metric like squared error in $\mu$-law space. However, to start with, let's just do linear mean squared error. Should be OK for loud audio.

Issue 2: Feedback Error Instability¶

Initially I trained the model like

training_data = ... # Generate lots of mathematically exact example input/output pairs model = train(training_data, epoch_count = 100)

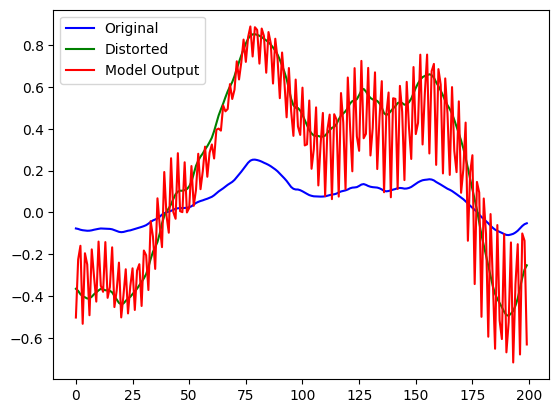

which often worked, but some fraction of the time, the model would grow to exhibit eventual oscillatory instability. It would tightly track the correct value for a while (perhaps a few thousand samples), but would eventually start to oscillate about the correct value like this:

Given that the validation loss during training looked so good, the most plausible theory I could think of here was that the model was growing a (not-strictly-necessary) dependency on the feedback pathway. E.g. it may have been relying on in[t-1] - out[t-1]. During training, these two values would have been generated by our tanh distortion algorithm, not by the model, and so it would have had an exact mechanical relationship that the model could perhaps take advantage of.

However, during inference, all of the out values are generated by the model itself, not by our tanh distortion function. So, if the model makes a slight error in predicting an output value, this error will get cycled back into the model during the next inference step, and the error could compound or oscillate as we see here.

To fix this, we need to teach the model that the $[o_n, o_{n+1}, ..., o_{n+m-1}]$ buffer of previous output values we're feeding it is not totally trustworthy; since these values are generated by the model during inference, they will have some error.

The simple fix I came up with was to inject some noise into the feedback pathway during training. The noise in the feedback pathway simulates the error that the model introduces. To perform well, the model needs to learn to treat the feedback audio as only approximate, which makes it robust against feedback error. This worked great, totally eliminating the dynamic instability.