This year at NeurIPS, there was a workshop on Creativity & Generative AI.

Alongside Jillian Arnold, Kelly McKernan, and Ted Chiang (talk notes here), I was invited to give a talk and share my perspective on generative AI with the machine learning research community.

I chose to talk about the parallels between AlphaGo’s impact on professional Go, how that connects with what I’ve been seeing in my corner of the art world today (photography and entertainment art industry), and some musings on life, art, and meaning.

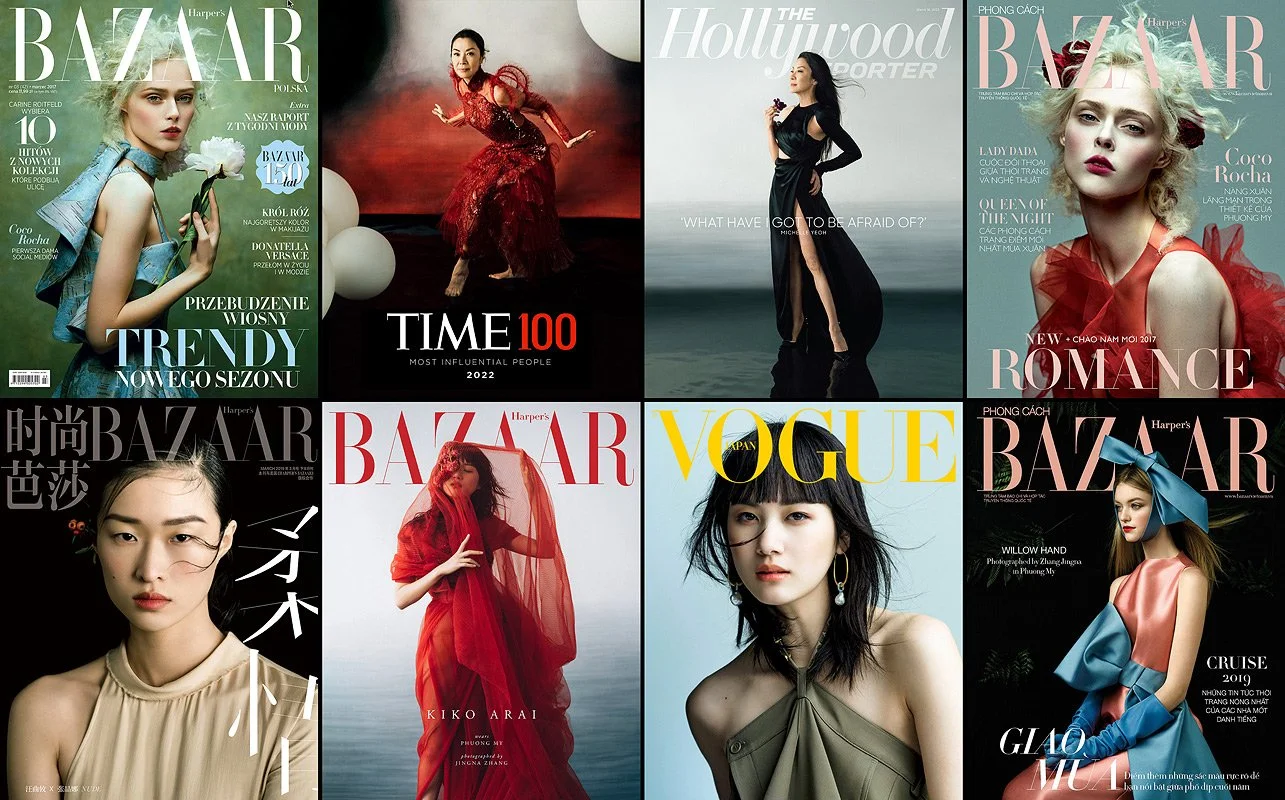

Background: Art & Competition

I’ve been a fashion and fine art photographer for nearly 20 years. My growing up was shaped by fascinations with computer science and micromouse at school, six years on Singapore’s national shooting team, and founding an esports team in StarCraft 2.

I grew up loving art while pursuing an Olympic dream, and because Go represented both artistic beauty and competition—it was an existence that uniquely blended both worlds.

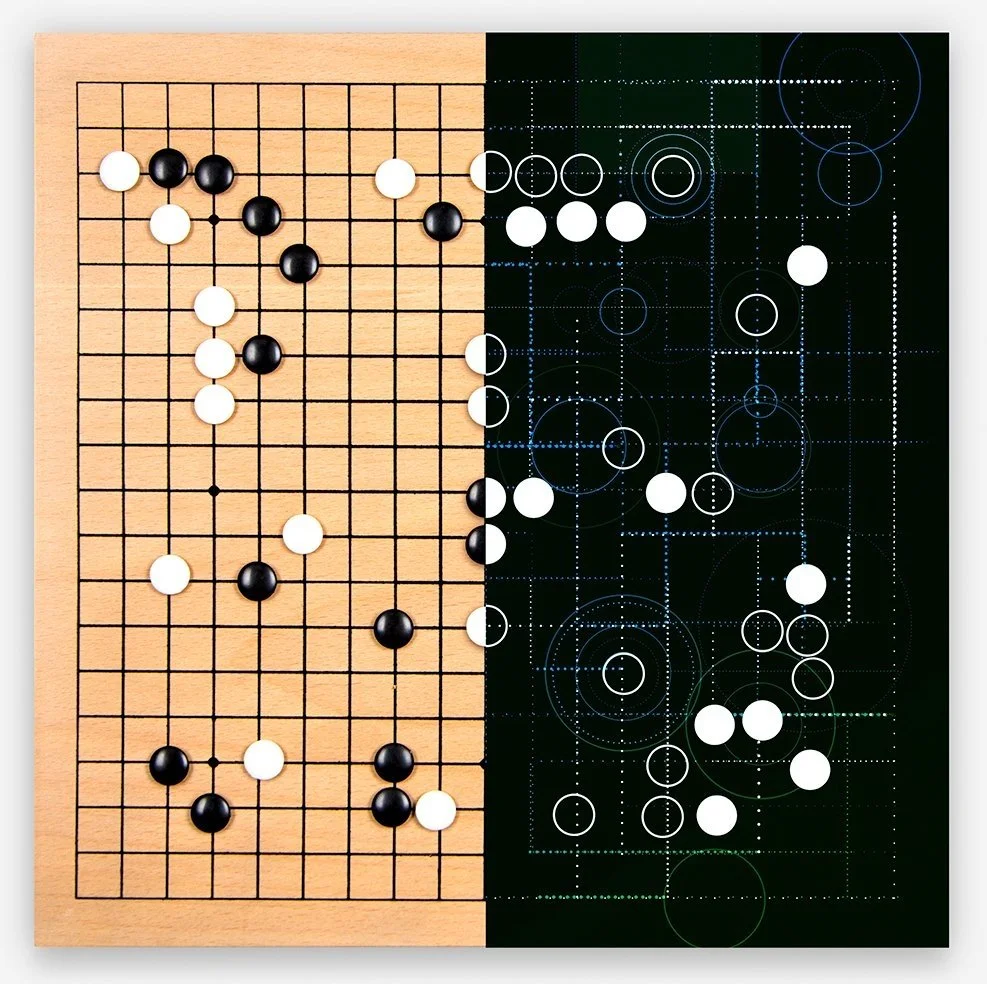

The World of Go

Image: Go Seigen Memorial Exhibition

Go is an ancient strategy board game played with black and white stones. I loved the sound of a stone placed on board, the simplicity of its rules, the elegance of its design, and how a player's style was an expression of who they were, their moves like brushstrokes in a painting.

I played Go on and off over the years, spent some time living with professional players, and through photography, covered major world tournaments like the Ing Cup.

The path to mastery wasn’t easy. To become a professional player, children often left home at the age of 6-7 to study at Go academies in big cities.

I had a friend who at the age of 11 or 12—in order to play in the finals of an important tournament—was not told by the adults when his mother passed away. He never got to say goodbye.

Go is beautiful to me, but it is not without sacrifice. People dedicate their whole lives to the art, and for many years, it was seen as the pinnacle of games to solve in AI, and players and fans alike loved it for its mystery, and how it remained unsolved.

AlphaGo

Lee Sedol, Ing Cup 2008 / Photo: Jingna Zhang

In 2016, DeepMind created AlphaGo, an AI that defeated Lee Sedol—one of the world’s best Go players.

This was a landmark moment because up till then, most researchers thought that such a feat was still years away—even AlphaGo’s own team thought the same when interviewed in the AlphaGo documentary.

Lee Sedol’s loss was a marvel of achievement in AI, and a devastating loss for the Go world.

After the event, I sat for days contemplating what this meant for human creativity, and our pursuit of art and purpose.

From Go to Art

A year before AlphaGo, I ran into Yann LeCun at a conference and asked him about the possibility of training an AI in the style of my work. The gist of his answer was that it wasn’t a question of if, but when. While many professional artists had experimented with GANs by then, most people—just like those in Go—thought that today’s generative AI models would still be a fiction of the far future.

After AlphaGo, I began to look at AI development and research through a new lens.

I was trying to build an artist platform around that time and ended up attending a business program, going to tech and founder conferences, and connecting with people in machine learning to learn more about recommendation systems. This opened my eyes to AI developments that could impact creative industries, and I began to think with some certainty, that the timeline for AI in art would shorten, and come much sooner than imagined, maybe in five years.

Six years later, DALL-E 2 arrived in 2022. At the time I took to describing it as “the creator’s AlphaGo moment” to artist friends. Because even though it didn’t arrive perfected, you could see that the technology was fundamentally different from what came before.

Photography & Copyright

Michelle Yeoh by Jingna Zhang / TIME 100 / THR

People get into art for a variety of reasons, and a lot of it is for passion and self-expression. Many of us start off with little next to nothing. In photography, we would often shoot for magazines for very little pay, or sometimes even for free or out of pocket if we lived in competitive cities like New York.

People who have a salaried job or gig work typically receive payment in return for the work they do. As a freelancer and solo creator, there are no salaries or benefits—putting our work out there is part of the work—so that we can sell and license our art later.

We accept the risks of less or no upfront pay because in return, we can own the copyright to what we create. Knowing that I can sell and license the work later is a big part of what made photography a possible career path for me. The framework of copyright provided me the protection I needed for an income—and it’s how I make a living and get paid for my work.

Left: Jeff Dieschburg; Right: Original photograph by Jingna Zhang

Two years ago, I found out that a man in Luxembourg took one of my photos, mirrored it for a painting, and entered it into an art biennale. It won an award, was offered for sale for thousands of euros, and when he was found out, he claimed it was his right to use my work because he found it online.

After hearing that he hired a lawyer first, I sought legal counsel to protect myself, and we went to court when the art biennale said they couldn’t tell if the work was copyright infringement or not. (I won the case)

It felt like we had reached a saturation point where many people thought just like this guy did, and I hoped that by fighting this, I could create an example for smaller artists, both to provide them with a reference, and a story to defend themselves from people who might try to argue the same points.

Most people understand that you can’t take a Game of Thrones poster or picture of Taylor Swift and make money off them. But somehow, selectively, people seem to forget this fact when it comes to names they don’t know.

It’s been a constant battle for creatives online to get our rights respected, and as this case unfolded, generative AI began making its way into our world.

After AlphaGo—Life, Art, and Meaning

In 2020, a professional Go player took his own life due to depression. He was known to have disliked using AI for practice, and was said to have hated the idea of following moves determined as the best by AI.

In the entertainment art industry, we lost an artist to similar struggles as AI began taking the stage at various studios before the layoffs started hitting the news.

In a tribute interview with teammates and top players, Fan Tingyu, a 9dan pro said, “There are times when it’s inevitable to feel like Go has become boring, like it no longer held the colors it once did. … Now, when you spend a lot of time coming up with a new move … all it takes is for AI’s evaluation to give a low rating, and showing exactly how many ways it can counter you—and you will feel like the value of creativity itself has diminished.”

Go has continued on after AlphaGo. People use it for learning, practice, and game reviews with AI tutors, but these upsides did not come without a cost.

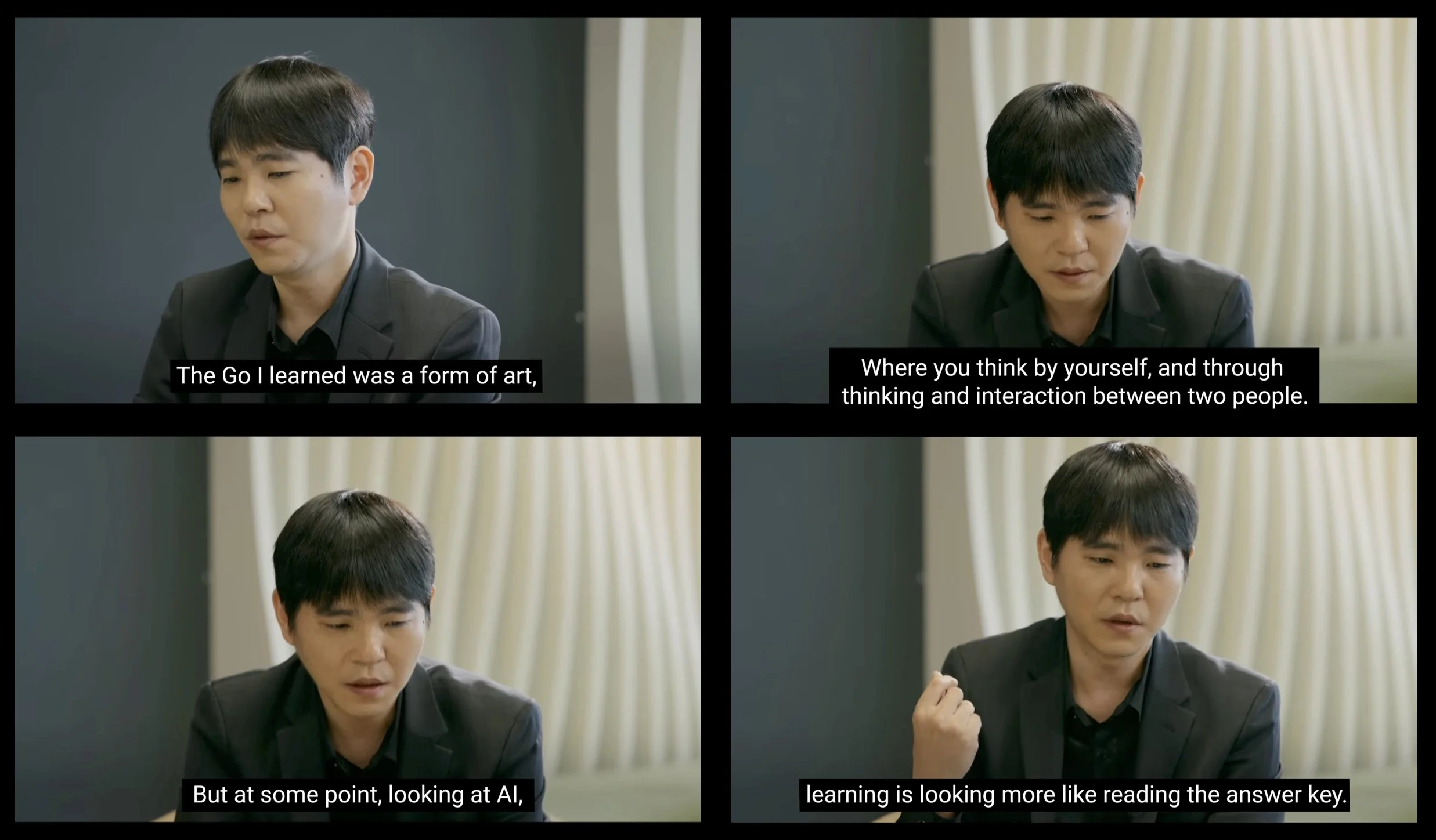

In 2019, Lee Sedol retired, he couldn’t defeat AI.

In an interview with Google this year, he said:

“The Go I learned was a form of art … But at some point, looking at AI, learning is more like reading the answer key.”

When asked if he would be a professional Go player again if he could go back in time—he said no.

This was someone who gave his life to Go. Someone so impactful that the world of Go shaped itself to his games. For him to say that he wouldn’t be a pro again—it was heartbreaking.

AI didn’t just defeat Lee Sedol in technical ability, it defeated his spirit. It changed his relationship with what he saw as a form of art, and made him regret pursuing the path he had chosen in life.

The fact that humanity has been fully surpassed in this domain—as much as we can learn from it—has not come without cost.

As the race towards more capable AI continues, we need to contend with what it means for humanity as we automate away more and more of art creation and meaning.

When you replace expression and purpose so that we can be more optimized by following the best paths determined by AIs—what becomes of the human experiences we cherish?

Art, Unlike Go—

Professional Go continues to exist, remaining a human-only spectator sport. But this is not the same case with art.

For artists, gen Al is not just a technical demo like AlphaGo was—these are entire replacement machines, designed by taking the very work we have made, without our consent, to replace the life and work that artists have built throughout our lives.

For many of us who do art, these are not just a simple picture on the internet—our work is our identity, a life we have dedicated to our craft and our dreams—and it feels like it's now being fed through a grinder, without any regard for what we feel, and what will happen to us.

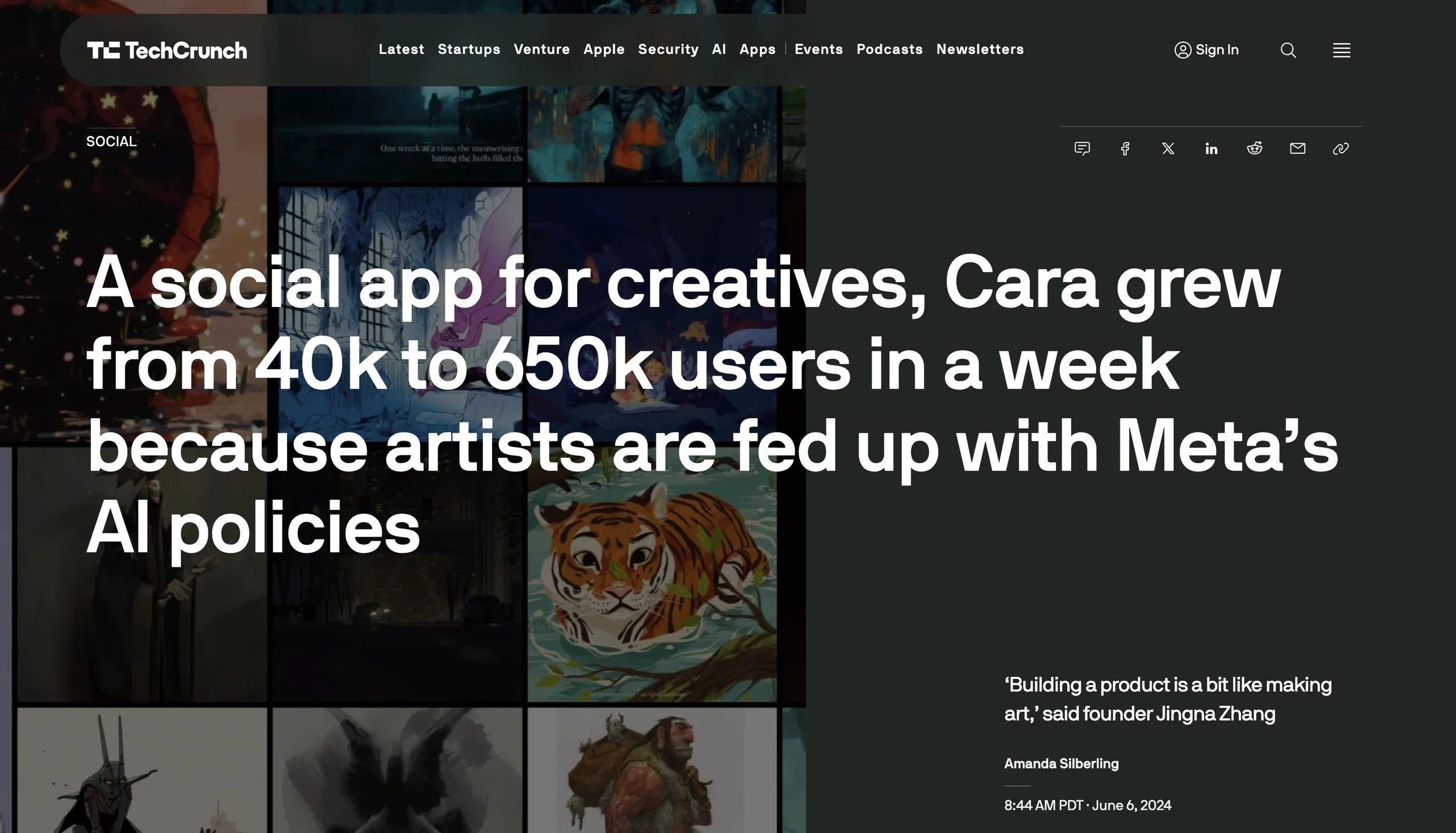

Taking Action

I created Cara in 2022 so there would exist a platform where people could easily find human artists. Despite it being a volunteer-built and community-supported platform, we’ve grown to over a million users in beta, validating that people feel a real need for human connection in art and digital spaces.

At art conventions, we constantly hear people share that Cara had a significant, meaningful impact on their lives—and they wanted to know if there were more people building tools that could help protect their work. I thought that NeurIPS would be a perfect place to share this question.

Before coming to the conference, I wrote a recommendation letter for a PhD applicant, and his statement of purpose really resonated with me:

"I am fortunate that my two-year exploration in AI research gave me the privilege to witness the entire process of how the rise of Generative AI divided the world into two groups: advantaged groups that gain a lot from AI, and disadvantaged groups that undergo a loss out of AI.

Attention comes to the former who masters, manipulates, and mobilizes AI, but always neglects the latter as the superseded and forced recipient of AI. Having witnessed this division, I am determined to invest myself in aligning and auditing Generative AI to prevent its misuse and help disadvantaged groups in this new AI era."

— Chumeng Liang, developer of Mist

I understand the pursuit of capabilities research is exhilarating, but research to support creative communities affected by generative AI remain vastly underexplored, and that should change.

I’m sharing these stories not to make a case against progress, but to ask for more thoughtful development, and to please consider the human impact of what you are working on today.

-

At the end of the conference, I met a number of people who expressed interest in helping with Cara or were looking for ideas on building tools that can help artists impacted by gen Al.

If you're in academia or research and interested in working on these problems, I'm happy to chat about best practices and info on gathering artists’ requests and feedback.

I appreciate the opportunity that NeurIPS and the creativity & generative Al workshop gave to artists to share our stories this year, and I hope more conferences will follow in these footsteps. Thank you.

-

Related posts:

If you enjoy my writings, consider supporting with a coffee to keep Cara running so I’ll have more time to essay! 😊