The idea that more free speech also fosters more democracy has failed because of social media. Regulating them can help, but what we really need is radical transparency.

Lesen Sie diesen Text auf Deutsch.

Freedom of expression; pluralism; holding truth to power; a common respect for the virtues of accuracy and objectivity; the belief that, in a marketplace of ideas, the best information eventually rises to the top: These were the foundational ideas that used to define a democratic information space, and they stand in stark contrast to the dictatorial model, with its censorship and secret police. They were ideals I imbibed growing up: My parents were Soviet dissidents arrested by the KGB in 1978 for distributing censored literature, like Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, that told the truth about the Soviet system of penal colonies. At night, they would listen to banned Western radio stations through the fog of Soviet jamming, desperate for more information – for the heteroglossia of opinion that was a sign of true democracy.

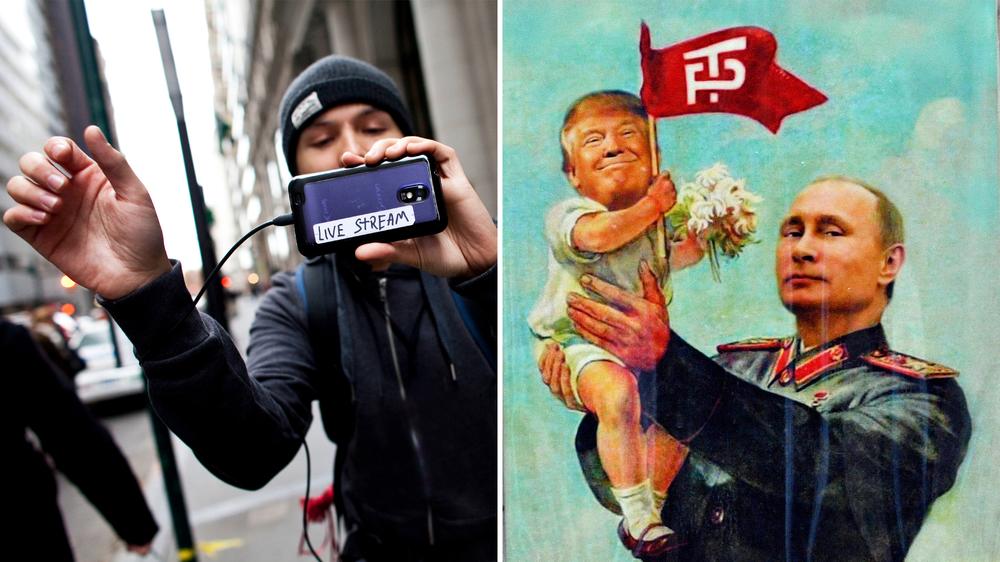

But today, those formulas have been turned upside down. Freedom of expression is used as an excuse to flood people with so much digitally powered disinformation that it has become impossible to tell truth from lies, and it’s far from clear whether the "marketplace of ideas" metaphor holds true any longer, or whether accurate information will rise to the top. We have seen pluralism tip into polarisation so extreme, and partisan groups living in realities so different, that it has become impossible to agree on a common set of facts, making democratic debate impossible. We are seeing a whole generation of politicians who no longer seem to be frightened of the truth and who are happy to throw up a big middle finger to factual discourse. And these trends are as prevalent in democracies as they are in dictatorships, blurring the line between the two.

So, what went wrong? How can we fashion a democratic information space for the future? One that guarantees a full, free and fair debate? One where democracies can make decisions based on evidence-based deliberation?

Consider the Philippines. As my parents were enjoying the pleasures of the KGB in the 1970s, the Philippines was ruled by Colonel Ferdinand Marcos, a U.S.-backed military dictator, who used the army to impose censorship and to indulge in horrific forms of torture, leaving victims’ skulls stuffed with their underpants by the side of the road, so as better to intimidate passers-by. The Marcos regime fell in 1986, when millions poured out into the streets to demand an end to censorship and torture. Today, the Philippines has some of the highest use of social media in the world. Twentieth century-style censorship would be nearly impossible to impose here. But the new president, Rodrigo Duterte, is not only rehabilitating Marcos’ reputation, he has also found new ways of inflicting old oppression.

Glenda Gloria, an editor at the independent news website Rappler, remembers the Marcos years. In the 1980s, she was a student journalist covering the regime’s torture of opposition figures. Her boyfriend was arrested for running a small independent printing press and had electrodes attached to his genitals.