For those of you who forgot the gameplay of hangman: the challenge is to guess a word. You can pick a letter, one at a time. If the word contains the chosen letter, it is indicated at the correct location(s). If the word does not contain the letter, you loose a turn and get one step closer to hanging. To win, you need to find the word before you die hanging. In our version, we will let the user choose a dictionary (English or Dutch), and we keep track of users and his high-scores.

4.1. A first custom widget

We first discuss the HangmanWidget, which is a custom widget that encapsulates the game itself: it allows a user to play one or more games. It does not deal with updating the user’s score, instead it indicates score update events to other widget(s) using a signal.

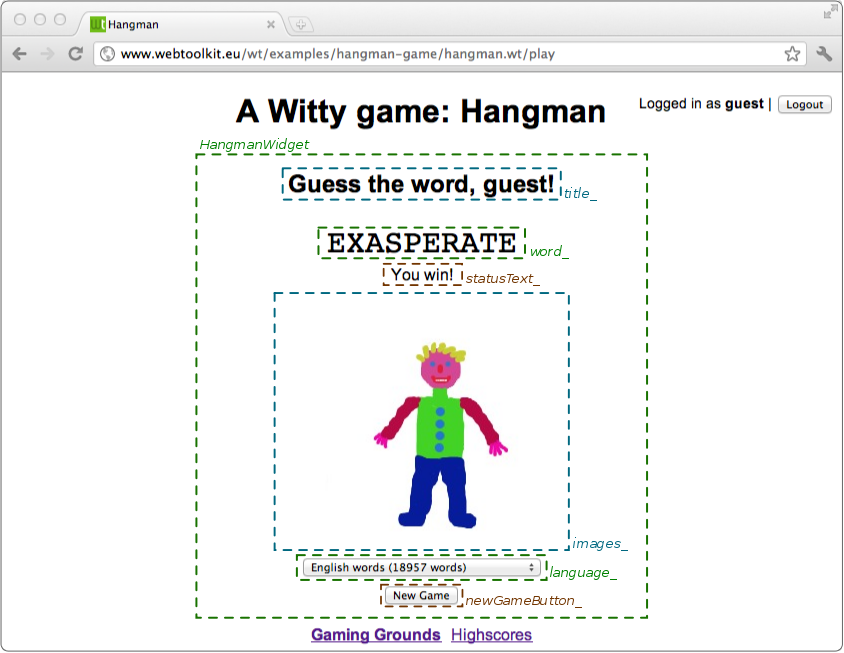

The following screenshot shows how the widget is composed of different widgets:

The HangmanWidget combines widgets provided by the library

(WText: title_, statusText_,

WComboBox: language_), and three

custom widgets (WordWidget: word_, ImagesWidget: images_ and

LettersWidget: letters). As you will see, custom widgets are

instantiated and used in pretty much the same way as library widgets,

including reacting to events generated by these widgets.

With this information, we can implement the class definition.

HangmanWidget declaration

class HangmanWidget : public Wt::WContainerWidget

{

public:

HangmanWidget(const std::string &name);

Wt::Signal<int>& scoreUpdated() { return scoreUpdated_; }

private:

Wt::WText *title_;

WordWidget *word_;

ImagesWidget *images_;

LettersWidget *letters_;

Wt::WText *statusText_;

Wt::WComboBox *language_;

Wt::WPushButton *newGameButton_;

Wt::Signal<int> scoreUpdated_;

std::string name_;

int badGuesses_;

void registerGuess(char c);

void newGame();

};This widget is implemented as a specialized

WContainerWidget. This is a

typical choice for widgets that combine other widgets in a simple

layout. We declare one public method scoreUpdated(), which provides access

to the signal that will be used to indicate changes to the user’s

score as he plays through games. A

Signal<int> used here, indicates that an

integer value will be passed as event information, and will reflect

the score update itself (positive when the user wins, or negative when

the user loses). Any function or object method with a signature

compatible with the signal may be connected to it and will receive the

score update.

The private section of the class declaration holds references to the contained widgets, and state related to the game.

The constructor implementation shows some resemblance with the hello world application we discussed earlier: widgets are instantiated and event signals are bound. There are some novelties however.

HangmanWidget constructor

using namespace Wt;

HangmanWidget::HangmanWidget(const std::string &name)

: name_(name),

badGuesses_(0)

{

setContentAlignment(AlignmentFlag::Center);

title_ = addNew<WText>(tr("hangman.readyToPlay"));

word_ = addNew<WordWidget>();

statusText_ = addNew<WText>();

images_ = addNew<ImagesWidget>(MaxGuesses);

letters_ = addNew<LettersWidget>();

letters_->letterPushed().connect(this, &HangmanWidget::registerGuess);

language_ = addNew<WComboBox>();

language_->addItem(tr("hangman.englishWords").arg(18957));

language_->addItem(tr("hangman.dutchWords").arg(1688));

addNew<WBreak>();

newGameButton_ = addNew<WPushButton>(tr("hangman.newGame"));

newGameButton_->clicked().connect(this, &HangmanWidget::newGame);

letters_->hide();

}Wt supports different techniques to layout widgets that may be combined (see also the sidebar): namely widgets with CSS layout, HTML templates with CSS layout, or layout managers. Here, we chose to use the first approach, since we simply want to put everything vertically centered.

The LetterWidget exposes a signal that indicates that the user chose

a letter. We connect a private method registerGuess() to it, which

implements the game logic of dealing with a letter pick. Notice how

this event handling for a custom widget is no different from reacting

to an event from a push button, making that widget as much reusable as

the widgets provided by the library (assuming you are in the business

of hangman games).

To support internationalization, we use the tr("key") function

(which is actually a method of WWidget

which calls

WString::tr(),

to look up a (localized) string given a key. This happens in a message

resource bundle (see

WMessageResourceBundle),

which contains locale-specific values for these strings. Values may be

substituted in these strings using a "{x}" notation and the

arg()

method of WString, as used for example for the

"hangman.englishWords" string which has as actual English value

"English words (\{1\} words)".

For completeness, we show below the rest of the HangmanWidget implementation.

HangmanWidget: game logic implementation

void HangmanWidget::newGame()

{

WString title(tr("hangman.guessTheWord"));

title_->setText(title.arg(name_));

language_->hide();

newGameButton_->hide();

Dictionary dictionary = (Dictionary) language_->currentIndex();

word_->init(RandomWord(dictionary));

letters_->reset();

badGuesses_ = 0;

images_->showImage(badGuesses_);

statusText_->setText("");

}

void HangmanWidget::registerGuess(char c)

{

if (badGuesses_ < MaxGuesses) {

bool correct = word_->guess(c);

if (!correct) {

++badGuesses_;

images_->showImage(badGuesses_);

}

}

if (badGuesses_ == MaxGuesses) {

WString status = tr("hangman.youHang");

statusText_->setText(status.arg(word_->word()));

letters_->hide();

language_->show();

newGameButton_->show();

scoreUpdated_.emit(-10);

} else if (word_->won()) {

statusText_->setText(tr("hangman.youWin"));

images_->showImage(ImagesWidget::HURRAY);

letters_->hide();

language_->show();

newGameButton_->show();

scoreUpdated_.emit(20 - badGuesses_);

}

}4.2. Unleashing (some of) Wt’s power

Until now, we introduced a rather unique way to develop web

applications, and a powerful building block for reuse: the

widget. The next widget in the Hangman game that we will tackle, is

one we’ve already used just earlier: the ImagesWidget. It

illustrates an important aspect of the library that highly enhances

the user experience for users with an Ajax session (which should be

the majority of your users). One of the most appealing features of

popular web applications like Google’s Gmail and Google Maps is an

excellent response time. Google may have spent quite some effort in

developing client-side JavaScript and Ajax code to achieve this. With

little effort – indeed almost automatically – you can get similar

responsiveness using Wt, and indeed the library will be using similar

techniques to achieve this. A nice bonus of using Wt is that the

application will still function correctly when Ajax or JavaScript

support is not available. The ImagesWidget class, which we’ll

discuss next, contains some of these techniques. Hidden widgets are

prefetched by the browser, ready to be displayed when

show()

is called.

ImagesWidget: implementation

ImagesWidget::ImagesWidget(int maxGuesses)

{

for (int i = 0; i <= maxGuesses; ++i) {

std::string fname = "icons/hangman";

fname += std::to_string(i) + ".jpg";

WImage *theImage = addNew<WImage>(fname);

images_.push_back(theImage);

theImage->hide();

}

WImage *hurray = addNew<WImage>("icons/hangmanhurray.jpg");

hurray->hide();

images_.push_back(hurray);

image_ = 0;

showImage(maxGuesses);

}

void ImagesWidget::showImage(int index)

{

image(image_)->hide();

image_ = index;

image(image_)->show();

}

WImage *ImagesWidget::image(int index) const

{

return index == HURRAY ? images_.back() : images_[index];

}In the constructor, we meet one more basic widget from the library:

WImage, which unsurprisingly corresponds

to an image in HTML. The code shows how widgets corresponding to each

state of the hangman example are created and added to our

ImagesWidget, which specializes a WContainerWidget. Each image is

also hidden – we’ll want to show only one at a time, and this is

implemented in the showImage() function.

But why do we create these images only to hide them? A valid alternative could be to simply create the WImage that we want to show and delete the previous, or even better, to simply manipulate the image to point to another URL? The difference has to do with the response time, at least when Ajax is available. The library first renders and transfers information of visible widgets to the web browser. When the visible part of web page is rendered, in the background, the remaining hidden widgets are rendered and inserted in the DOM tree. Web browsers will also preload the images referenced by these hidden widgets. As a consequence, when the user clicks on a letter button and we need to update the hangman image, we simply hide and show the correct image widget, and this no longer requires a new image to be loaded. An alternative implementation would have caused the browser to fetch the new image, making the application appear sluggish. Using hidden widgets is thus a simple and effective way to preload contents in the browser and improve the responsiveness of your application. Important to remember is that these hidden widgets do not compromise the application load time, since visible widgets are transferred first. A clear win-win situation thus.

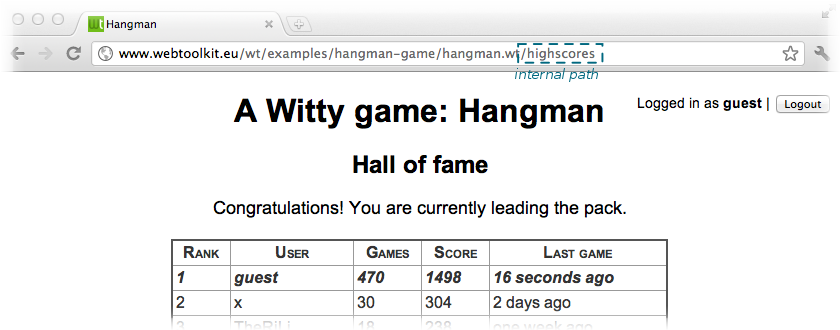

4.3. Internal paths

Ignoring the login screen for a moment, then our application has two

main windows: the game itself and the high scores. These are

implemented by the HangmanWidget which we discussed earlier, and a

HighscoreWidget (which we will not be discussing in this

tutorial). Both are contained by a

WStackedWidget, which is a

container widget which shows only one of its contained children at a

time (and which, in all honesty we should have used to implement the

ImagesWidget, were it not that we wanted to explain a bit more about

preloading of contents). Unless we do something about it, a Wt

application presents itself as a single URL, and is thus a single-page

web application. This is not necessarily bad, but, it may be better to

support multiple URLs which allows a user to navigate within your

application, bookmark particular “pages”, or put links to them. It

also is instrumental to unlock the contents within your application to

search engine robots. Wt provides you with a way to manage URLs which

are subpaths of the application URL, which are called “internal

paths”.

Internal paths are best used in combination with anchors (provided by

another basic widget, WAnchor). An

anchor can point either to external URLs, to private application

resources (which we’ll not discuss

but are useful for dynamic non-HTML contents), or to internal

paths. When such an anchor is activated, this changes the

application’s URL (as one could expect), and the

internalPathChanged()

signal is emitted. Thus, to respond to an internal path change, we

connect an event handler to this signal.

This is the implementation of the method that we connected:

HangmanGame: internal path handling

void HangmanGame::handleInternalPath(const std::string &internalPath)

{

if (session_.login().loggedIn()) {

if (internalPath == "/play")

showGame();

else if (internalPath == "/highscores")

showHighScores();

else

WApplication::instance()->setInternalPath("/play", true);

}

}Thus, if a user is logged in, we show the game when the path is

"/play" and the high scores when the path is "/highscores". For

good form, we redirect all other paths to "/play" (which will end up

triggering the same function again). In our game we make

authentication (whether a user is currently logged in) orthogonal to

the internal paths: in this way a user may arrive at the game using

any internal path, log in, and automatically proceed with the function

for that internal path. You may imagine that this is what you want in

a complex application: the login function should not prevent the user

from directly going to a certain “page” within your application.

We did not discuss other parts of the hangman game example

application: namely how user scores are stored, and the authentication

system. Database access is implemented using a Wt::Dbo, which is a

C++ ORM that comes with Wt. This tutorial

introduces the database layer. The authentication module, Wt::Auth,

as used in this example, is introduced here.