Present-day Concrete Cross. Courtesy of Google Maps. A few years ago, NPR Morning Edition released a story about spy satellites that caught my attention during a morning commute to work. Reporter Danny Hajek covered a story about mysterious 60-foot-long (18-meter-long) concrete crosses found in the Arizona desert titled, “Decades-Old Mystery Put to Rest: Why Are There X’s in the Desert?” The NPR story details how two adventurers, Chuck Penson and Pez Owen, spotted mysterious crosses while flying cross-country in Owen’s Cessna. The crosses spotted by Penson and Owen were just a handful of targets laid out over a 16-by-16-mile (26-by-26-kilometer) grid across the desert near Casa Grande, Arizona. Wondering what the crosses were for, the pair reached out to the US Army Corps of Engineers, since one of the bronze positioning markers at the center of one crosses stated “Army Map Service” with a date of 1966. According to the story, the US Army Corps of Engineers response made the connection between the concrete crosses and the CORONA program. [1] I’ve got a filing cabinet in my basement filled with declassified NRO documents relating to CORONA (and a few other programs), and I had never heard this tale of concrete crosses in the desert within a CORONA context. The rest of the article hit a Cold War armchair historian’s sweet spot: parents who worked on secret programs they couldn’t talk about, what the CORONA satellite program did for US military planners and intelligence analysts, and the pride of surviving the threat of nuclear war. Admittedly, the tale was captivating: two adventurers venturing upon a “secret” that was hidden out in the open desert for decades. However, once I heard the word “CORONA” mentioned, I knew something was amiss. As a space history researcher and frequent Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requestor, I’ve got a filing cabinet in my basement filled with declassified National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) documents relating to CORONA (and a few other programs), and I had never heard this tale of concrete crosses in the desert within a CORONA context. [2]  Design of a Casa Grande Aerial Target. What was CORONA?CORONA was the program name for a series of photographic intelligence satellites that provided coverage of the Soviet Union, China, and other areas from its first successful flight in 1960 until its retirement in 1972. Intelligence analysts used satellite imagery for a variety of analytical purposes, ranging from monitoring Soviet strategic force development and deployment to estimating the size of grain production in Communist countries. The program’s major accomplishment early in its history was photographing all Soviet medium-range, intermediate-range, and intercontinental ballistic missile sites during the early 1960s, proving that there indeed was a “missile gap” but it was wholly in favor of the American side. [3]  CORONA mission profile. (credit: NRO) Dr. Kevin Ruffner’s coverage of the program in his 1995 monograph “CORONA: America’s First Satellite Program,” gives a comparison table of CORONA cameras, as well an excellent explanation for a layperson:

Source: Ruffner, CIA 1995 The first photo provided by the CORONA system was of the Mys Shmidta airfield in August 1960 (Image 4). The image had an estimated ground resolved distance around 40 feet (12 meters) and the runway is barely discernable as a small, straight, light-colored strip, with the parking apron as a nearby light-colored rectangle. [5]  Mys Shmidta airfield, 1960. North is toward upper-left of photograph. (credit: NRO) Questioning the story’s ingredientsI could not come up with a satisfactory answer why the government would build a fixed optical range with such large targets specifically for CORONA in a post-1966 timeframe and not mention it in documentation anywhere. One website states the targets were calibration targets for CORONA from 1966 until 1972. The targets were supposedly abandoned due to shifting caused by subsidence from nearby ground water pumping. [6] Even Wikipedia has a page about these “Corona Satellite Calibration Targets.” Keen observers will note that while NRO references are listed at the bottom, no specific document is identified with information on either Casa Grande or the concrete cross dimensions. [7] As someone who knows a little about CORONA, I wondered about why the programmatic specifics didn’t match up with the concrete cross myth… er… “story.” I had even more questions to mull over:

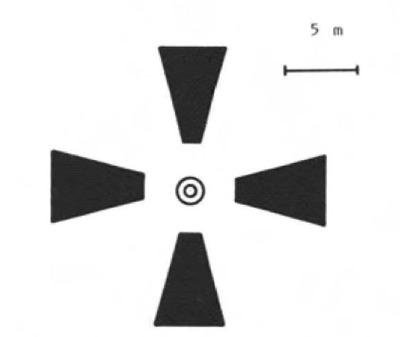

I received a banal response after emailing the webmaster of BornTourist.com and questioning some of the “facts” listed on their Corona Calibration Target page:

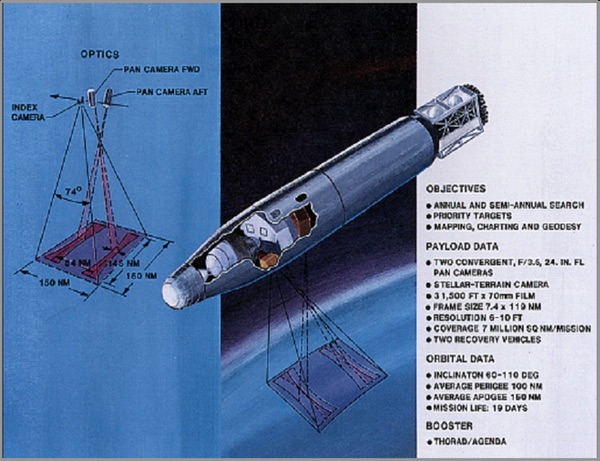

Overlay of Concrete Cross locations near Casa Grande, Arizona. Courtesy of Google Maps. A seemingly plausible explanation, right? The problem is that, regardless of the physics of aerial photography, there is no mention of Casa Grande within the NRO collections on CORONA. None. There was mention of an optical target range but it wasn’t fixed and was nowhere near Casa Grande, Arizona (more on that in a future article). I could not come up with a satisfactory answer why the government would build a fixed optical range with such large targets specifically for CORONA in a post-1966 timeframe and not mention it in documentation anywhere. The webmaster did indicate, however, his sourcing for the webpage: “…Local newspapers and interviews [were] the main source of information to link the Corona project to the targets.” The bitter taste of misinformationI re-read the NPR story online (and spin-off articles from local Arizona newspapers) and came away believing the tale was chock full of hasty generalizations and a flawed logic linking the concrete crosses to the nation’s first photographic satellite program:

What disturbed me the most was there was no mention of contacting the CIA or NRO or reviewing the declassified document collection on CORONA by either the adventurers or the reporters writing the story. When Executive Order 12951 declassified the CORONA satellite program on February 22, 1995, the amount of available information increased from scant mention via press releases to thousands of pages and actual imagery. [10] To handle this deluge of declassified information, the NRO instituted a public reading room at their Chantilly, Virginia, headquarters; due to a dearth of in-person visitors, a web-based portal now provides the information to the public. At the time of the story’s publication, Hajek or subsequent reporters could have used any number of released mission reports from the early CORONA missions to check their hypothesis. If specific missions were not already available, the reporter could have requested documentation using FOIA as I have done many times. I emailed the pair of adventurers about the establishment of linkage between the crosses and CORONA:

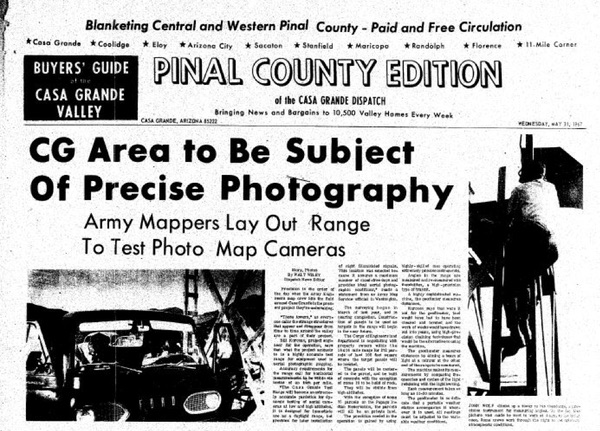

Interestingly enough, the Arizona adventurers did accidentally find a clue to the (documented) calibration network for the National Reconnaissance Program satellites: “We did find another interesting marker on the grounds of Fort Huachuca, southeast of Tucson. It looks kind of like a test pattern of vertical and horizontal bars of various lengths.”  Tri-Bar Array at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Courtesy of The Center for Land Use Interpretation. A fallen recipeBelieving that an optical range of this size and complexity could not stay hidden, I changed my research approach and looked in a very unlikely place: a public newspaper archive. I found what I believe to be the answer on the front page of the Casa Grande Dispatch (Pinal County Edition), dated May 31, 1967: “CG [Casa Grande] Area to be Subject of Precise Photography.” [12]  Casa Grande Dispatch, May 31, 1967. Courtesy of NewspaperArchive.com The idea that the Casa Grande range was developed for the CORONA program is asinine when looking at the timelines of range construction, stories about the range’s purpose twice posted on the front page of a local newspaper, the government photogrammetry description, and the technical aspects of what the satellites required for calibration. Walt Wiley’s front-page story tells of a US Army Corps of Engineers effort to create “…an extremely accurate yardstick for dynamic testing of aerial cameras at low and high altitudes.” A follow-up article on October 8, 1968, provides estimated costs and timelines, and a curious statement by Roger Lewis, an aide to Arizona Representative Morris Udall: “I was told the markers would be used for photography testing for aircraft at low or extremely high altitude.” The next sentence is conjecture on the part of Lewis: “[Lewis] added that it was his impression that ‘high altitude’ aircraft would also include satellites.” Lewis’ reason or agenda behind this statement of conjecture is unknown. [13] And to hammer home the linkage to aerial photogrammetry, I found this description from John O. Phillips the Chief of the Geodesy Division, Coast and Geodetic Survey, circa 1966:

The idea of announcing a super-accurate photogrammetry range for reconnaissance satellites in a public document and newspaper front page (twice!)—easily available to the Soviets—during its construction phase is one of the worst examples of operational security ever… not to mention extremely unlikely. Myth busted (?) but not deadAs of 1968, information concerning satellites performing photographic intelligence remained classified, but a widely suspected “open secret.” On October 1, 1978, President Jimmy Carter spoke at the Kennedy Space Center, acknowledging the US government’s use of “spy” satellites for the first time:

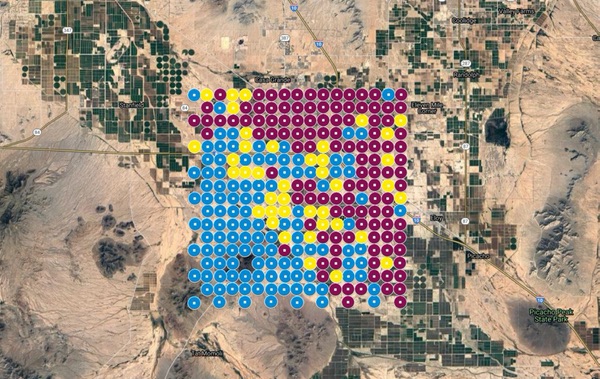

The idea that the Casa Grande range was developed for the CORONA program is asinine when looking at the timelines of range construction, stories about the range’s purpose twice posted on the front page of a local newspaper, the government photogrammetry description, and the technical aspects of what the National Reconnaissance Program photographic satellites required for calibration. The use of satellites for reconnaissance and surveillance ostensibly remained close hold until the declassification of the NRO in 1992 and the release of CORONA programmatic information in 1995. In the decades after the 1995 declassification (and prior to the NPR story), the NRO and CIA declassified numerous Photographic Evaluation Team (PET) Reports for CORONA and GAMBIT missions. [15] Inside each report is a list of mobile and fixed targets used for photographic evaluation. While a few sites are listed inside Arizona—near Fort Huachuca and Luke Air Force Base—they are comprised of the tri-bar optical test pattern used by the US government since the early 1950s, not 60-foot-wide concrete crosses. Note the date on the caption: 1966, which matches the time period of the Army Map Service bronze markers on the crosses.  Typical Mobile Target Array in 1966. (credit: NRO) While the facts presented here argue against the interpolated “logic” of the CORONA/concrete cross connection, the allure of the story continues. Numerous online forums have perpetuated the story; at least one group of academicians have used the crosses as a springboard for award-winning artistic and creative analysis, and a major publication (National Geographic) included the crosses in an article about security and surveillance. [17] With this type of viral momentum, this story likely won’t die, but will continue to be a false example of “derring-do” during the Cold War. What else perpetuates misinformation more than an air of mystery, selective information analysis, incomplete information, and a feeling of being in the know? Sounds like the perfect recipe for a CORONA conspiracy theory. [18] References

Joseph T. Page II is a freelance writer located in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the US Government. He can be reached for comments or criticisms at josephtpageii.com. Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam. Home |

|