📅 Last updated: September 15, 2025

☕ Welcome to The Coder Cafe! Today, we will talk about performance in the context of latency and user experience. Get cozy, grab a coffee, and let’s begin!

Have you ever clicked away from a website because it took too long to load? Of course, you did, and you're not alone. In our fast-paced digital world, users expect instant access to information and services. Latency—the time it takes for our device to communicate with a server and get a response—can make all the difference between whether users stay or leave. Let's explore how latency impacts user experience and what we can do to mitigate it.

When we talk about latency in the context of user experience, we're not speaking about seconds but milliseconds. Research shows that users perceive a website as slower or less efficient for every addition of 100 ms latency.

For a service deployed online, like websites or applications, making a strong first impression is critical. Google's research showed that users form an impression of your website's speed within the first two seconds of interaction. If the first impression feels slow, users are more likely to leave, and many may never come back. For instance, 53% of users will abandon a mobile website if it takes longer than 3 seconds to load.

Speed doesn’t just affect impressions; it impacts business performance, too. For example:

Amazon reported that a 100-millisecond increase when loading their website results in a drop of 1% in sales.

Google reported that a 500-millisecond increase to return search results resulted in a drop of 20% of the traffic.

There are three main strategies to reduce latency from the perspective of a user:

Make it faster

Anticipate user actions

Give the illusion of speed

Let’s break down these strategies:

The most straightforward approach is to make server responses faster.

We can achieve this through different techniques, such as optimizing a critical code path in our code, adding caching, making a database faster, or using CDNs. Yet, it isn’t the scope of this issue to cover all the techniques, as it would require a much longer discussion, as you can imagine. Let’s instead focus on the two other solutions.

We can also anticipate when users are likely to need certain content and load it ahead of time. Therefore, we can reduce the latency from the perspective of the users (called the perceived latency).

Without anticipation: The user requests content, and only then does the website or app start loading it:

With anticipation: The system preloads some content before the user even requests it:

A couple of real-world examples:

Netflix preloads parts of a video while the user is still browsing the content library, ensuring that a video starts almost instantly.

Facebook preloads parts of pages when users hover over links, reducing the latency for users.

Gmail begins loading an account in the background as soon as the user types their username, and even before they enter their password.

Instagram begins uploading photos in the background while the user is still writing the caption, before they tap the upload button.

Sometimes, we can’t make things faster, yet we can make it feel faster.

One illustration of this technique is exponential progress bars, where the rate of progress decelerates exponentially over time. Such progress bars give the users the impression that a task is almost done. For example, the following bar shows a rate of progress close to 90% while, in fact, the task was only completed at 50%:

In the case of a progress bar showing the real progress, users would be less willing to wait “just a bit more” for their task to complete:

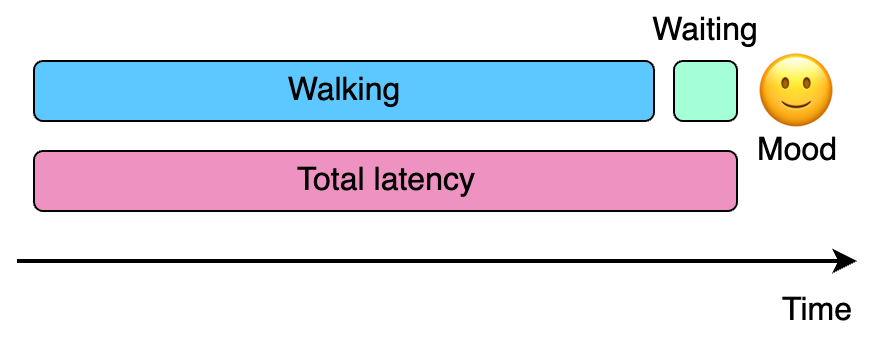

Another example of giving the illusion of speed comes from airports, and I find this one genuinely astonishing.

The Houston airport faced a high ratio of complaints from people saying they were waiting for their luggage for too long. As this time to deliver the luggage was incompressible, they decided to go with another option: making the airplanes land further away from the terminal.

When passengers walk for one minute to reach the carousel and then wait nine minutes for their bags, they feel more frustrated by the waiting time than when they had to walk for eight minutes but only wait two minutes.

Before:

After:

This approach worked because occupied time (here, walking) feels shorter than unoccupied time (here, standing at the carousel). And complaints dropped to near zero.

How can we apply this idea to software?

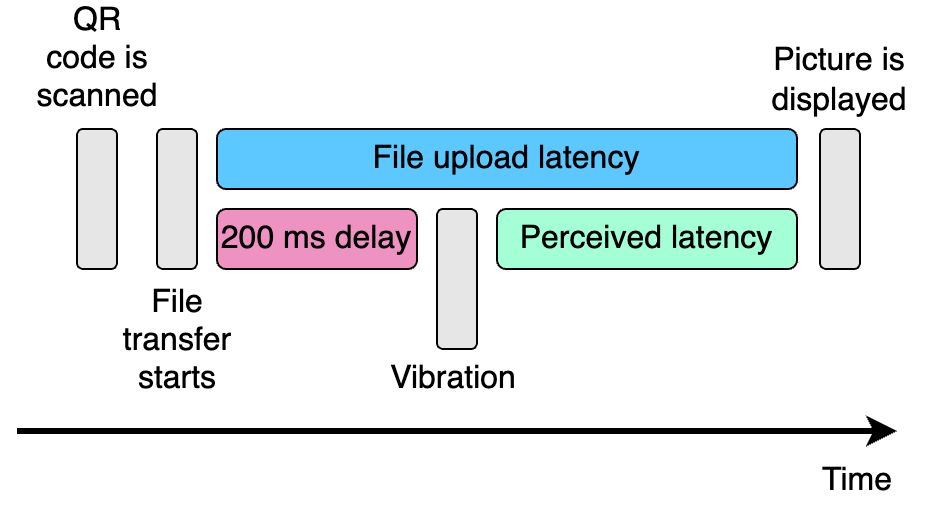

The Cool Maze application provides a nice illustration of this example. Cool Maze lets users easily share content, such as photos, from their phones to another device. For example, if we want to transfer a picture from a photo to a computer:

On a computer, the user opens the Cool Maze website (coolmaze.io), which displays a QR code:

Using the Cool Maze mobile app, the user selects a file to share and scans the QR code using their phone’s camera.

Once the QR code is scanned, the app vibrates to confirm, and the file is uploaded to the website, where it is instantly displayed:

Roughly speaking, the workflow is the following:

The latency to upload a file can’t be reduced, and there’s no way to anticipate any action, as the gatekeeping to start the upload is to scan the QR code. Yet, what Valentin Deleplace, the author of Cool Maze, ended up doing is to add a 200 ms delay before the vibration:

During this brief 200 ms delay, the file is already being uploaded in the background. By the time the phone vibrates, part of the work has already been done, making it feel faster to the user.

I genuinely love this example, and it perfectly illustrates this section. When we can’t optimize our solution anymore and cannot anticipate a user action, remember that giving the illusion of speed can become an option.

Remember that when it comes to latency, making things fast isn’t nice to have; it’s a critical feature. Working on the solutions described—1. make it faster, 2. anticipate, or 3. give the illusion of speed—is essential for building a smooth and satisfying user experience.

❤️ If you enjoyed this post, please hit the like button.

💬 What did you think about the examples described? Let’s discuss it in the comments.