Takeaways

- A new video by Vancouver-based documentarians About Here explains why the United States and Canada have the fewest elevators among rich countries: elevators here cost three to four times more.

- Because elevators make taller buildings pleasant to live in, this is a big barrier to building more walkable, accessible, transit-rich, and age-friendly cities.

- Allowing smaller elevators is a key incremental step, but the deeper problem is that our needlessly unique technical standards lock us out of the world’s common elevator market.

Phones that refuse standard chargers. Half-strength sunscreen. Ounces. All symptoms of the American tendency to pretend the rest of the world hasn’t already settled on a better way to do things.

Now, add another symptom: The fact that you’ve probably never lived in a building with an elevator.

The United States has the fewest elevators in the rich world, with Canada only a bit ahead. That’s true even after you adjust for our lower shares of multifamily housing—while also being part of the reason for our lower shares of multifamily housing. The fundamental issue? Elevators in these two countries cost three to four times more to build and to operate than in other rich countries.

The result is that unlike in Spain, Austria, Taiwan, or Australia, Americans and Canadians almost never see a residential building with fewer than 50 homes that has an elevator. This restricts elevators, along with the convenience, age-friendliness, and accessibility they bring, to the biggest buildings and the biggest cities.

It’s been this way for decades, but nobody has been talking about it. Until now.

Inspired by a groundbreaking 2024 report on this subject by the Center for Building in North America, Sightline Institute teamed up with one of Cascadia’s finest YouTubers, Uytae Lee of Vancouver-based About Here, to investigate why, as he puts it, “North America kind of sucks at elevators.”

How we locked ourselves out of the global elevator market

As in his other videos about how to make cities better, Lee packs a lot into 14 minutes.

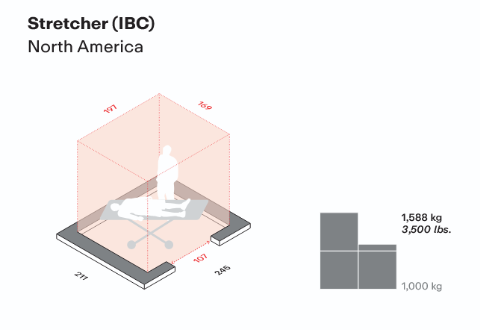

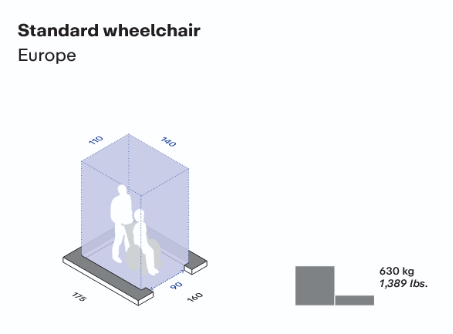

Some of the issue, as he says, is just size. Inch by inch, elevator shafts in the United States and Canada have become 85 percent bigger than the global baseline required to fit at least two people, one of them in a wheelchair:

But a bigger share of the problem is that, as with the metric system, the US and its code-writing institutions have been using their own unique set of technical standards for no particular reason except habit. Canadian institutions have, as usual, tagged along with their more populous neighbor. This has continued even as almost every other country in the world has gradually “harmonized” its elevator rules to the similarly reliable but differently calculated standards in Europe.

It’s not really our fault that it played out this way. But it’s stranded us on a technological island.

The United States and Canada—the countries that first popularized passenger elevators by inventing the skyscraper—now represent less than 5 percent of the world’s new elevator and escalator installations. Few companies bother to play in such a small market with such a big barrier to entry. This, in turn, keeps our prices high, our elevator buildings scarce, and our market small.

Join the 15,000+ readers who get Sightline Institute’s latest research.

Get our latest research and news summaries straight to your inbox.

Almost finished! We need to confirm your email address. To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you.

←

Almost finished! We need to confirm your email address. To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you. In the meantime, here are other newsletters you may be interested in:

How to get more elevators in our cities and towns

North America’s problem isn’t only that its elevators are expensive. It’s also that they’re so expensive that they make multifamily buildings expensive. This makes an especially big difference on smaller parcels, where the only direction to go is up, and in smaller cities, where markets rarely support buildings of 50 or more homes.

So, unlike their peers around the world, most North Americans have just learned to live without.

In a six-story building, a US elevator and its future operations add something like $310,000 to the upfront cost of a building—roughly the same as an entire extra home that everybody in the building must collectively pay for. (That’s $175,000 for the elevator, shaft, and machinery; $40,000 for hoistway opening protections; and $95,000 for the present value of $7,500 per year in future operating and maintenance costs.) If most people aren’t willing to pay that much, the builder has to forgo the elevator. And because so few people want to live on the fifth or sixth stories of a building without an elevator, that can send the financial math for the entire building into collapse.

The math gets especially harsh for the smallest buildings, fewer than 25 homes or so, because America’s high elevator costs must be shared among so few households.

So, what can a city, state, or province do to change this?

One step would be to allow smaller elevators in smaller buildings—specifically, in the sort of buildings that aren’t currently getting any elevators at all. It’d make sense to use the same standards various states and cities have been adopting for sunlight suites: small-lot apartment buildings of up to six stories and 24 homes.

Another step would be to join the international elevator market by harmonizing regional or local codes to the international standard, just as most other countries have. Washington legislators came close to doing this in 2025, but understandably balked at the cost of the code work and training required. (Larger states, or maybe those sharing a border with a country that has already harmonized, might weigh those transition costs differently.)

As a half-measure, a government body might formally state its support for national code bodies to finally harmonize with the global system. Though many people see this as inevitable, nothing will happen without effort.

Individuals and institutions can help, too. Late last year, a group of accessibility and housing organizations started assembling as the “National Coalition for Elevator Reform” by joining a policy statement about the need for more elevators in the United States. It’s currently collecting logos and signatures. (Sightline’s is one.)

If this effort succeeds, it’ll require a lot of people to hear and share the story Lee tells in the video above. Maybe you’d like to be one of the first.