Thomas Keller is fidgeting on the bench next to mine in the empty courtyard of the French Laundry. There’s a slight quaver in the chef’s voice, and he tells me he is nervous. This is not something he is accustomed to doing, he says — asking a critic to leave.

He’s sure I’m a nice person, he tells me, but he doesn’t know my intentions, and he doesn’t want me in his restaurant.

I had pulled into Yountville 45 minutes earlier to visit the favorite child in the Keller family of restaurants. My party of four was held outside the charming stone building nursing sparkling wine while we waited for our table, and though the sun had mostly faded, I’d kept on my extra-large, celeb-off-duty sunglasses.

To ensure something resembling an ordinary diner’s experience, some of my restaurant critic peers wear disguises. I am not an anonymous critic. When I assumed this role a little over a year ago, I chose to publish an updated headshot rather than try in vain to scrub my photos online. But I use aliases to make reservations so a restaurant can’t prepare for my visit in advance. Sometimes, to delay being identified as long as possible, I’ll arrive in an N95 mask or these sunglasses.

Article continues below this ad

The captain refilling our wine introduces himself as Patrick. Tonight, I am Margaret.

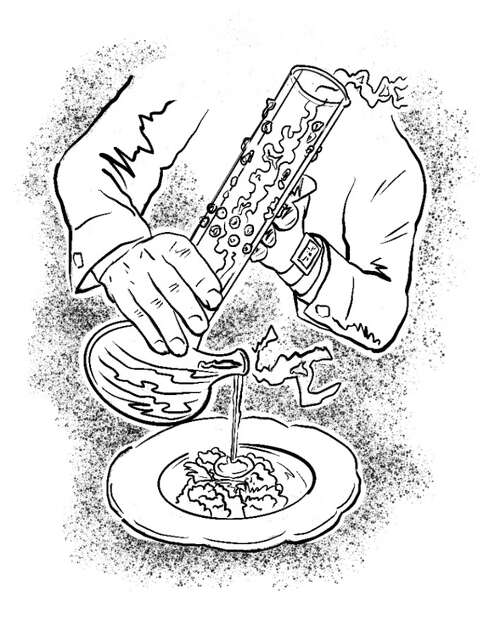

Thirty minutes after our reservation time, we are ushered through the restaurant’s iconic blue door and up a narrow staircase to an intimate room with three tables. The opening salvo of truffle vichyssoise is served, and then a general manager walks up to the table and directs me to follow him.

“If I’m not back in 10, send a search party,” I say breezily to my dining companions. We laugh. I don’t bring a jacket.

The manager leads me to a bench in the courtyard by the kitchen, under the branches of a sprawling tree.

Article continues below this ad

I wait but a few moments, and then before me is Thomas Keller, lanky in his chef’s whites.

“Thomas,” he says.

“MacKenzie,” I reply, shaking his hand.

“I thought you said your name was Margaret,” he says with a sardonic edge.

Left: Sean O’Hara stokes the fire in a wood-burning oven at the French Laundry in Yountville in 2017. Right: Laura Cunningham, co-founder of Thomas Keller Restaurant Group, and French Laundry chef Thomas Keller speaking while French Laundry chef de cuisine Ara Jo plates dishes in the kitchen.

Gabrielle Lurie/S.F. Chronicle and Aya Brackett/New York TimesTop: Sean O’Hara stokes the fire in a wood-burning oven at the French Laundry in Yountville in 2017. Above: Laura Cunningham, co-founder of Thomas Keller Restaurant Group, and French Laundry chef Thomas Keller speaking while French Laundry chef de cuisine Ara Jo plates dishes in the kitchen.

Gabrielle Lurie/S.F. Chronicle and Aya Brackett/New York Times

An exterior view of the French Laundry, seen in 2017.

Stephen Lam/S.F. ChronicleKeller does not know what I want from him, he says, or what I am doing at his restaurant. I’m not here to write a review, I tell him honestly. My predecessor, Soleil Ho, weighed in 2½ years ago, and it’s not customary to reassess so soon after. But I eat at restaurants I’m not planning on reviewing all the time, and my credibility demands that I visit one of the most celebrated and enduringly popular restaurants in the country — helmed by one of the most powerful chefs in the world.

Article continues below this ad

Thirty-one years after Keller took over this two-story former saloon in Napa Valley, the lore of the French Laundry is as deep as its wine cellar. Look no further than Keller’s recently released episode of “Chef’s Table: Legends.” I’ll give you the condensed version here; for the full experience, imagine B-roll of Keller hoisting an American flag over his culinary garden or zipping around Napa Valley in a sporty vintage BMW as you read.

After working at various Michelin-starred restaurants in France, Keller returned to New York in the late ’80s and opened a fine dining restaurant for the boom times. The market tanked, and Keller decamped for a job at a hotel restaurant in Los Angeles, from which he was fired a year later. In the “Chef’s Table” formula, this was his rock bottom, the moment when he realized something had to change. He bought the French Laundry, a rustic farm-to-table pioneer, and remade it in his own image. Three years later came Ruth Reichl’s 1997 New York Times review, which anointed the French Laundry “the most exciting place to eat in the United States.”

Keller enjoyed nearly two decades of accolades, both for the French Laundry and for Per Se, which he opened in Manhattan in 2004 and which quickly became New York’s most exclusive restaurant, frequented by the strata of diners who own islands. When the Michelin Guide came to the United States, each received three stars. Keller was everywhere — winning awards for his coffee-table cookbooks, selling his own line of Limoges porcelain, consulting for Pixar’s “Ratatouille.” For mere mortals, dinner at the French Laundry became a bucket list item, an anniversary splurge worth staying in a relationship for.

General manager Michael Minnillo speaks with Thomas Keller in the kitchen at the French Laundry in 2017.

Gabrielle Lurie/S.F. Chronicle

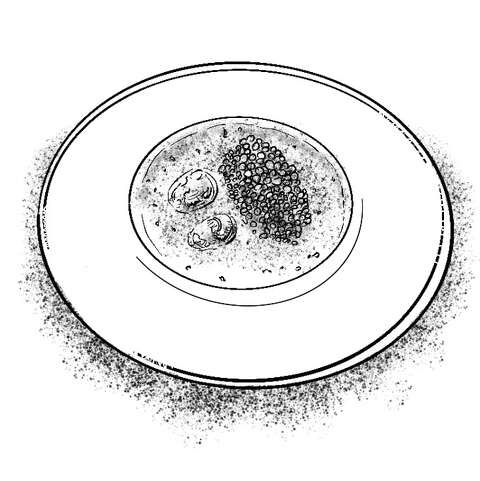

Left: Servers check the classic oysters and pearls dish prior to serving in 2017. Right: A quote is displayed inside the kitchen.

Stephen Lam/Special to the S.F. ChronicleTop: Servers check the classic oysters and pearls dish prior to serving in 2017. Above: A quote is displayed inside the kitchen.

Stephen Lam/Special to the S.F. Chronicle

Chefs work inside the kitchen at the French Laundry in 2017.

Gabrielle Lurie/S.F. ChronicleThen, in 2016, a bomb dropped: a scathing review of Per Se by New York Times critic Pete Wells. An alphabetical list of adjectives that appeared: “dismal,” “gluey,” “grainy,” “mangled,” “rubbery,” “swampy,” “terrible.” But of all the barbs, the one heard ’round the world was a line describing a mushroom soup “as murky and appealing as bong water.”

Article continues below this ad

Keller appeared to take the review in stride, writing in a public apology, “When we fall short, we work even harder.” He even seemed to have a sense of humor about it. In 2019, when Keller recognized Ho at the French Laundry, he sent over a glass bong — “the kind you use to smoke drugs,” Ho wrote — filled with mushroom soup.

The French Laundry made the Chronicle’s list of the Top 100 restaurants in the Bay Area that year. But after two more visits, Ho decreed it no longer worth the splurge in a 2022 review. A Norwegian king crab galette had “the pasty hybrid texture of a cheap fish ball and a Starbucks egg bite.” The desserts, once exhilarating, were “beige, repetitive and one-note.” The restaurant does not appear on the Chronicle’s 2025 Top 100 list, which I co-wrote with my colleague Cesar Hernandez.

But tonight, the criticism that is fresh in Keller’s mind is the Times’ double-barrel review of Per Se and the French Laundry, which ran in November on the occasion of their respective 20th and 30th anniversaries. Melissa Clark, filling in as a critic after Wells’ departure, described Keller’s restaurants as “stuck in a bubble of complacency” and “tediously, if inconsistently, fine.” While Clark once found Keller’s culinary sense of humor fresh, a de-stuffification of the hallowed halls of fine dining, his dishes now read as tired. “Mr. Keller’s food is no longer exceptional in a dining landscape that he is largely responsible for creating,” she wrote.

Now Keller wants to talk about her with me, but her name escapes him.

“Melissa?” I volunteer.

Article continues below this ad

“She lied,” Keller tells me, with visible pique. “She lied until the very last minute.”

I had heard whispers about Clark’s visit to the French Laundry, the details of which were not included in her review. Keller wouldn’t leave her alone, food world insiders murmured, and he made sure to inform her that his new chef de cuisine was a woman — a first for the French Laundry under Keller.

Clark, a cookbook author and recipe developer who appears in New York Times videos, is a recognizable figure, with her glossy red hair and angular jaw. When she dined at Per Se, she was spotted. So for Yountville, she donned a blond wig and aviators and assumed the cover story of a yoga instructor named Emma. When Keller approached her in the courtyard, he asked whether he knew her from New York. Clark, who later confirmed the details of this story to me but declined to comment on the record, believed Keller was not certain of her identity and decided to stick to her role. No, she replied, he must be mistaken. She lived in Santa Monica.

After a lengthy tour of the grounds, Clark’s party finally sat down, and it was then that she realized Keller and his team had seen through the wig. Servers began to toy with her. Where did she like to hang out in Santa Monica? What were her favorite restaurants in Los Angeles?

The first course arrived. Her companions received soup in espresso cups, but for Clark? She got the bong.

Keller’s publicist, Pierre Rougier, told the Chronicle in an email after my visit that “it was insulting, an awkward charade, and odd that (Clark) remained in disguise.” Past critics, he said, were recognized over the years, and when “greeted by name, they acknowledged it and went about their job.”

The day after Clark’s piece ran, Keller clapped back on Instagram, posting a quote by the pompous, pointy-headed critic from “Ratatouille: ” “The bitter truth we critics must face is that, in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is more meaningful than our criticism designating it so.”

Through the kitchen windows I can see Keller’s brigade, heads down, preparing the food I thought I was here to eat. He gestures toward them. The young chefs working for him don’t deserve to have their work slighted, he tells me. He personally does not care about the reviews, he insists, but his staff? It gets to them. And for that reason, even though he doesn’t know me, even though he’s sure I’m a nice person, he does not want me here.

Mortifyingly, I want to cry. I can feel tears welling along my lower lashes. Partially this is because Keller’s vulnerability is arresting, like hearing your dad tell you he’s scared. But, straight-A student that I am, I’m also unaccustomed to being reprimanded, and this feels unfair. I have never met Keller before. I haven’t written a single word about him, positive or negative. Very much wishing I still had those sunglasses on, I tell him I’ll respect his decision if ultimately he wants me to leave, but first, may I tell him a bit about myself?

The French Laundry, I say, is quite meaningful to me. When my parents came to New York for my college graduation, they offered to take me to a celebratory dinner. Instead, I suggested we wait until I was back in the Bay Area and go to the French Laundry.

I had worked as a server throughout college and took it seriously, a student among professionals who departed for Danny Meyer restaurants and the recently opened Per Se. Only the best of us could work for Keller, and I wanted to experience his famed hospitality, back at the mother ship.

I remember what I wore that evening. I remember my delight at the salmon tartare cornets, the oysters and pearls, the coffee and doughnuts, all of which I’d pored over in the French Laundry cookbook. Eating those seminal dishes was like meeting a movie star; they were everything I had hoped for, if somewhat smaller in person.

We took photos. My dad feigned a heart attack for the camera when the bill arrived while I looked on, grinning. I took the menu and that old-timey clothespin affixed to the napkins back to New York. Both moved with me to seven apartments, rattling around in a box with concert ticket stubs and old love letters.

I tell Keller that I come from a restaurant family. My mother’s parents opened Henry’s Hunan on Kearny Street in San Francisco in 1974, and my cousins carry on their legacy today. Like Keller, my grandparents served a good meal to an open-minded critic on a charmed day, and that review changed their lives. How strange it is to now be on the other side, to hear this famous man’s voice catch as he tries to find a polite way to ask me to leave.

I feel the Napa Valley spring chill through my silk shirt, despite the heat lamp over my shoulder. A server brings us glasses of water, and I am grateful.

Keller asks me whether I know of his friend Michel Richard. After winning over Los Angeles with Citrus in the ’80s and Washington, D.C., with Citronelle in the ’90s, Richard trained his sights on New York. In 2013, he opened Villard Michel Richard. The New York Times savaged him, Keller tells me, and two years later, Richard was dead. Keller promises that when the time comes to pen his memoir, he will write about how that review led to the death of a good man.

Keller mourns an earlier era when, in his words, critics and chefs were on the same team. He references Michael Bauer, the Chronicle’s restaurant critic from 1986 to 2018, and describes him as a friend. (I reached out to Bauer to see what he thought of this characterization. “I have nothing but respect and admiration for what he’s achieved,” he wrote by email. “At this point if he wants to call me a friend I’m honored.”)

As a young chef, Keller says, he would rush to the newsstand at midnight, eager to read what the Times’ critic had to say. No longer. He gets it, he says. Newspapers must drum up controversy. What other reason could the Times have for hyperlinking to Wells’ eight-year-old review every time Per Se is mentioned in an article?

Keller then brings up Ho’s review of La Calenda, his Mexican restaurant that closed at the end of last year. It was one of Ho’s first reviews for the Chronicle and was exceedingly positive. But what Keller remembers is the headline — that La Calenda is “cultural appropriation done right.” He twists Ho’s favorable review into a slight. What does that even mean, he asks, saying that culinary cultural appropriation doesn’t exist in America, a nation of immigrants. In a melting pot, cultural appropriation isn’t a thing.

After 30 minutes in the courtyard, Keller decides it’s time to wrap up. OK, he says, that’s enough, let me walk you back inside. He tells me that he’ll feed me a little something before I go. I ask for clarity; if he still does not want me at his restaurant, I would rather get a jump on the long drive home. No, no, he says, that would be rude.

As he escorts me to the door, I detect a shift. The nerves are gone. He’s decided to cook for me, and he’s now telling his origin story, one you can hear on “Chef’s Table” or his episode of “The Bear” or his MasterClass or his ads for Hestan cookware.

As a young cook, he worked under a French chef, Roland Henin, at a beach club in Rhode Island. One day, Henin asked, “Thomas, do you know why cooks cook?” Keller’s hand is firmly gripping my elbow, urging me forward a few steps, then stopping me whenever he has a particularly important point to make, as he does now. “To nurture people.”

As I walk back into the restaurant and ascend the stairs to my table, I am cold and hungry, my mind is racing, and my body is vibrating. A man whose books and cookware I own, whose restaurants I revered as a young person in hospitality, has let me know that, despite my new big job, I am a guest in his house, and he will decide how my evening will progress.

In his email to the Chronicle, Keller’s publicist said the chef found our conversation “thoughtful and engaging, and MacKenzie did as well.”

I return to my table rattled. My dining companions have asked after my whereabouts twice; the staff told them Chef and I were having a “heart-to-heart.” There has been no additional food. Our reservation was for 7:45, and now it’s past 9 p.m. I whisper to my companions that I think we’re getting a grilled cheese sandwich and being sent on our way.

A server informs us that Chef Keller would like to cook for us, and a sommelier says he’s been asked to select our wines. Keller ends up sending an entire tasting menu. We make the best of it. There are the cornets, the oysters and pearls, the “mac and cheese.” We get exactly the type of special treatment I had been hoping to avoid by calling myself Margaret. He makes truffles rain — “apology truffles,” one of my dining companions remarks — and sends out a magnificent bottle of 2011 Ridge Zinfandel.

Between courses, a waiter sets our table with fresh silverware, and I notice my butter knife is placed the wrong way, blade out. My brain reels with paranoia. What does it mean? At a place like the French Laundry, such mistakes are not made.

It sounds silly now. It’s not like I thought Keller was going to fill my pockets with pie weights and drop me in the Napa River, and I presume that Clark didn’t think her mushroom soup was poisoned with anything other than rancor. But at a restaurant of this ilk, you pay for the privilege of submitting yourself wholly to Chef’s genius and his staff’s omniscient hospitality. You give yourself over to culinary surprise and delight. But what if that chef has decided you’re the enemy? If I had been in Clark’s position, I might have dug in as well, just to hold onto a shred of agency.

At 10:30 p.m., before the meat courses have even arrived, Keller whisks us away for a tour of the property, showing off his geothermal system (very cool), his china collection (massive) and his trophy case of plates signed by celebrities, including Woody Allen (hmm). Back in the courtyard, he motions to a stately tree to the right of the blue door, its branches growing up and around the second-story deck, intertwined with the restaurant. “She’s in the autumn or maybe even winter of her life,” Keller tells us with a wistful note in his voice. He had been trying to figure out what to do when she dies. What replacement tree could ever be as magnificent as this one?

He’s alighted on a solution. Keller is having a replica made by the people who do fake trees for Disneyland and Las Vegas. When the tree dies, the duplicate will arrive, and it will be as if nothing has changed.

We retake our seats for duck, beef and cheese courses and so, so much dessert. Finally, at 12:30 a.m., our server hands over a check presenter. “Dinner is compliments of Chef Keller,” the bill reads, with a big fat zero perching on the “total” line. It’s the ultimate display of power, Keller’s refunding of our prepayment of $1,831.75, tip included, and I drop my head into my hands. This is bad. Chronicle journalists are prohibited from accepting free meals from people we cover, but our server insists the refund has already gone through, there’s nothing to be done, you’re very welcome! I confer with my companions, and when our server returns, humble myself. Please, I say to him, you have to help me. I’m going to get in a lot of trouble.

OK, he says. Let me see what I can do.

When he returns, he brings a check for 93 cents. With tax, our total for the evening is one dollar. My friend, whom I’d previously Venmo’d for my portion, hands over his credit card, which our server runs for one dollar, and on the gratuity line, we add $1,830.75.

Weeks later, after I had told Keller I was writing this piece, his publicist contended to my editor via email that the meal was “free of charge.”

I told Keller I wasn’t going to write a review, and I meant it; I don’t have much to add to Ho and Clark’s recent critiques of the food. I will say that our servers put on the show of their lives, trying to save the evening, but all the cheerful professionalism in the world couldn’t cut through what had transpired, the inhospitality of it all.

Thirty years ago, critics lost their minds over Keller’s innovations, his puckish fusion of French technique and American cuisine. If, Keller seems to insist, he and his team can execute those dishes with perfection, day after day, shouldn’t the raves keep rolling in? And if they don’t? Those critics can hit the road.

A little before 1 a.m., I walk out of the blue door, pass under that majestic tree, get in my car and drive the hour and 15 minutes home.

In a statement made through Rougier nearly a month after my visit, Keller said: “Ultimately, it was my responsibility to feed and nurture them. I think we did that, and they had a wonderful time from what we could tell.”