Stories about Fractal Art

From Art and Mathematics Married by Computer

Introduction: Speaking loosely without using technical terms such as the Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension, a fractal is an object that is self-similar, i.e., a large part of it contains smaller parts that resemble the large part in some way; see

| Figure 0.1(A) | Figure 0.1(B) | Figure 0.1(C) |

| The Mandelbrot Set | A Julia Set | A Newton Fractal |

Figure 0.2. A "Treasure Map" (above) for Finding Julia Sets

and

A Julia Set Found on the Map

Our world has fractals everywhere exemplified by trees, mountains, blood vessels, mycelium strands, stock market graphs, weather patterns, seismic rhythms, ECG signals and brain waves. In its article entitled "How Mandelbrot's fractals changed the world," the BBC states that fractal geometry has practical applications in diverse areas including diagnosing some diseases, computer file compression systems and the architecture of the networks that make up the Internet.

The idea of fractal was not particularly new in mathematics for Mandelbrot's time or the computer age, as Georg Cantor introduced the prototypical

Cantor set in 1883 and various others appeared as shown inThe

Julia sets, representing their fractals and named after Gaston Julia, were largely ignored, however, because of the lack of technology to show their beauty, before the Mandelbrot set was born on a computer screen. The Cantor sets, the Julia sets and the Mandelbrot set are all subsets of the complex plane.| Figure 0.3. Classical Fractals in Mathematics (Refurbished by a Computer) |

| Koch Snowflake (1904) | Sierpinski Rectangle (1916) | Pythagorean Tree (1942) |

| Sierpinski Triangle (1915) | Pascal's Triangles with Modular Arithmetic | Devil's Staircase (1884) |

It was 1980 when Mandelbrot published his computer-generated image of a novel object, now called the Mandelbrot set, and completely altered the fate of fractals in art and mathematics. Mandelbrot, who once studied under Gaston Julia and later became an "IBM fellow," used the computer to visualize the fundamental dichotomy of the Julia sets, which is a special case of the Fatou-Julia Theorem and divides up the complex plane into two regions.

Thus born was an object that turned out to be astoundingly complex as well as beautiful, unimaginable from the dichotomy. It invigorated the interests in fractals by numerous mathematicians including Adrien Douady and John H. Hubbard, who named the object the "Mandelbrot set" and established many of its properties. Because attractive images of the Mandelbrot set can be generated by simple computer algorithms, it also found a way out of mathematical communities and into popular culture.

The NOVA program on the subject was broadcast by PBS in 2008 and stated, "Largely because of its haunting beauty, the Mandelbrot set has become the most famous object in modern mathematics. It is also the breeding ground for the world's most famous fractals. Since 1980, the set has provided an inspiration for artists, a source of wonder for schoolchildren, and a fertile testing ground for the science of linear dynamics." (Note: "linear" was probably a typo for "nonlinear.")

It is given by lighting up the invisible filaments of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set.

The Mandelbrot set conceals infinitely many subsets with exquisite details and captivating compositions. Moreover, the detailed patterns are dictated by the boundary of the Mandelbrot set comprising razor-thin "filaments" in the manner illustrated in

Mandelbrot defined fractals using the

Hausdorff dimension (aka Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension), which is a generalization of the familiar dimensions and quantifies the complexities caused by the self-similarity, roughness and irregularities not found in traditional Euclidean geometry. For example, the Hausdorff dimensions of a line and the boundary (perimeter) of the Koch snowflake shown inLike the Julia sets, the Hausdorff dimension was created in the 1910s and remained rather obscure before 1980 when the Mandelbrot set emerged and fractals became popular. In 1998, Mitsuhiro Shishikura proved that the Hausdorff dimension of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set is the same as the dimension of the plane, which is 2 and maximal for any objects lying in the plane. This effectively proved that the Mandelbrot set containing its boundary is

one of the most complex objects ever plotted on a plane.

Computer lovers attracted to fractal art soon came to realize that there are infinitely many varieties of Julia sets providing some of the most beautiful fractal art images. Meanwhile, the Mandelbrot set, initially created to show the whereabouts of the Julia sets classified into the dichotomy's two types, grew to be a well designed "map" on the complex plane to show how the wider and more detailed varieties of the Julia sets are distributed.

Many subsets of the Mandelbrot set, especially those showing "mini Mandelbrot sets," function as such maps as well. A

mini Mandelbrot set is a smaller copy of the Mandelbrot set, and it is known amazingly that any segment of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set tangles with infinitely many mini Mandelbrot sets. Most of them are so small they are generally invisible, but when a computer zooms in on them and they become visible, they may reveal unique, intricate and dazzling patterns surrounding them. The Julia sets "born" from such an object naturally inherit the intricate patterns.

The Mandelbrot set is about 1026 times as big as the mini Mandelbrot set; see

By comparison, the number of all stars in the observable universe is about 2 × 1023.

A Julia set "born" from the Mini Mandelbrot set of Figure 0.5(A);

Fatou and Julia were born too early to see computer-generated Julia sets.

A Julia set in color "born" from the mini-Mandelbrot set of Figure 0.5(C)

The late 1970s and the early 1980s were an exciting period for computer lovers as portable desktop computers such as Apple II not only became widely available but also grew into major entertainment devices boosting their popularity, thanks to the arrivals of "Space Invaders" and "Pacman" from Nintendo.

Since then, a large part of mathematics became experimental like chemistry and physics as younger mathematicians began to utilize computers as their research tools. They find clues and solutions by conducting simulations and numerical and graphical experiments on computers. The trend began mainly because they witnessed the debuts of the subjects where computers played an essential role, namely, "fractal geometry"

| Key Line Art Block Depicting "Chaotic" Wave of the Sea | Final Woodblock Print = Key Block + Color Blocks |

Between Hokusai's Woodblock Print and Computer-Generated Fractal Art

| Chaotic Julia Set | Julia Set in Color |

| in Fractal Geometry | in Fractal Art |

| Chaotic Julia Set | Julia Set in Color |

| in Fractal Geometry | in Fractal Art |

A Julia set (in color) born from the "Mandelbrot Moon" shown below

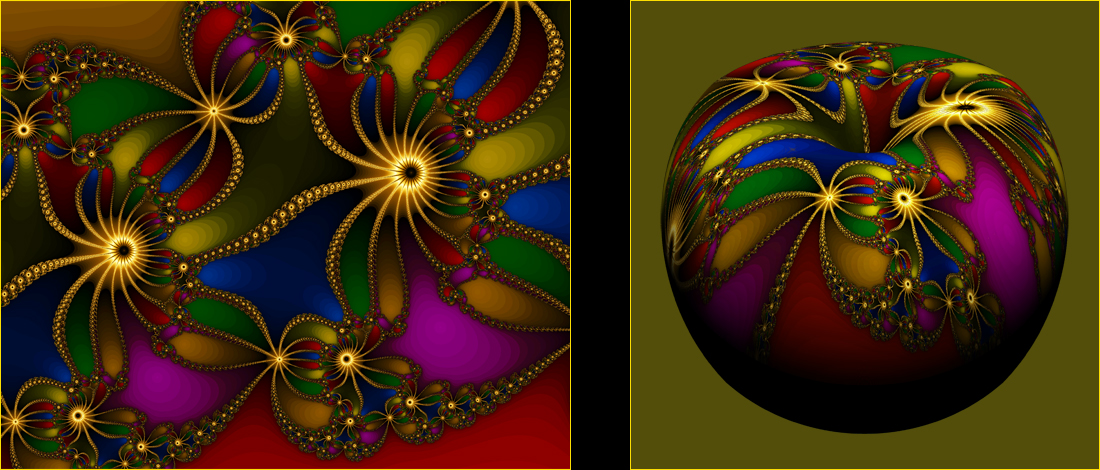

A Mini Mandelbrot set painted on a sphere for a change; see Gallery 3D.

A chaotic Julia set born from the "Mandelbrot Moon" shown above; cf. Figure 1.2(G).

Chaos was basically born as a brand new subject in 1974 from biologist Robert May's computer simulations of population dynamics through the dynamical system called the logistic equation. He then discovered an extremely complicated sequence of numbers that was unlike any of the population changes he had observed earlier and that reacted "sensitively" to a minuscule perturbation on its number to drastically alter its behavior. He called these sequences and the source of the sequences "chaotic".

Like "fractal," the word "chaos" was used as a mathematical term for the first time in 1975 when the American Mathematical Monthly published "Period Three Implies Chaos" by T.Y. Li and James Yorke. The paper inspired by May's discovery received a great sensation especially because there appeared very little difference between chaotic and random outcomes even though the former resulted from deterministic processes.

A fractal from the area where chaos was discovered.

Another fractal from the area where chaos was discovered.

The idea of chaos quickly evolved into comprehensive

chaos theory in science and at the same time its affinity with fractal art became clearer. As we'll see, it is the aforementioned sensitivity of chaos that causes drastic and unpredictable changes of colors and patterns in the image, and the boundary of the Mandelbrot set turned out to be exactly where the set is chaotic.As we have seen, the boundary is razor-thin and borders between the two regions in the complex plane comprising totally opposite characters defined by the dichotomy. It is not surprising that such a border becomes "chaotic" like in human interactions. A Julia set, which is also defined as the boundary of another object, became known to be chaotic as well and its chaotic tendency gets more pronounced if it is born from nearer the boundary of the Mandelbrot set.

Chaos contributes to fractal art by adding randomness, unpredictability and irregularities, and, while it makes the artwork more exciting and creative, excessive chaos may generate overwhelming noise and disorder. Thus, balanced chaos is a key to success in fractal art and one way of accomplishing it is to capitalize on the property of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set by tweaking the parameters in the dynamical system when we engage in fractal plotting.

Is chaos too little, too much or balanced in this image ?

Googling we can find a host of

websites displaying numerous computer-generated fractal art images that are often stunningly beautiful. It indicates that a large population not only appreciates the digital art forms but also participates in the eye-opening creative activities. Since computer use is essential for such aspirations, a fairly large part of this article is devoted to show how to program a computer and plot popular types of fractals generated by simple dynamical systems. It is not a text on computer programming and instead tells the general principles in everyday language easily translatable to a computer language.Central to our programming are

iterations comprising repetitions of thousands (or occasionally millions) of a simple process per "pixel" defined by a dynamical system. Through iterations our computer zooms in and miraculously reaches a "picoscopic" object like the mini Mandelbrot set ofParticularly exciting in fractal plotting is, therefore, the moment the fractal image generated by our personal program emerges on our computer screen. Even if it turned out not to be an artistic masterpiece, it may still stir our imaginations in the part of mathematics that is in fact quite deep and still filled with unknowns. One might even discover a thing or two in the relatively young field of fractal geometry in which computer experiments often lead the way. It is plain fun.

A Julia set born from the Mini Mandelbrot set of Figure 0.6(D)

"Lions," "Elephants" and "Seahorses," etc. are star actors in the Julia set scenes.

A Julia set found on the Treasure Map of Figure 0.2

A Julia set found on the Treasure Map of Figure 0.2

A Julia set born from the biggest Mini Mandelbrot set of Figure 0.7(A);

Note the bifurcation pattern on the "leaves" given by the "branches."

§ 1. Preparatory Mathematics

As mentioned at the outset, the text in this article is meant as an optional reading and is not needed in appreciating the fractal art images. On the other hand, people who wish to understand fractals in some depth by following the article need to know (a) elementary algebra and geometry of complex numbers and (b) beginning calculus. In addition, people interested in learning fractal plotting should have (c) some basic computer programming experience. Courses covering (a), (b) and (c) are available in high school.(a) includes the practice of writing a complex number z as a point

For each complex number

The only ideas we need from (b) are a

sequence of numbers that may converge or diverge and the derivative and a critical point of a function where the derivative vanishes.

See Fractal Coloring for the Step-by-Step Coloring Algorithm for the Image

Generated by the Mandelbrot Equation

We now introduce several preliminary ideas.

Orbits and Dynamical Systems: When we solve a mathematical problem using a computer, we frequently do it by exploiting what the machine does best, namely an iteration. It means repeating a certain process over and over, often for thousands or even millions of times, at a blinding speed. To see how it works, consider the best-known equation in fractal plotting, which we call the Mandelbrot equation for convenience:

(1.1) zn+1 = zn2 + p , with

where zn+1, zn and p are complex numbers and p is called a

parameter. The iteration index n is especially important for fractal plotting and it is there for us to iterate the equation to generate a sequence of complex numbers once the value of p and initial value z0 are given. For instance, letz0 = 0, z1 = z02 + p = 02 - 2 = -2 , z2 = z12 + p = (-2)2 - 2 = 2 , z3 = z22 + p = 22 - 2 = 2 , · · · ,

i.e., z0 = 0, z1 = -2 , z2 = 2 , z3 = 2 , · · · , z30 = 2, z31 = 2, · · · ,

which is called the

orbit of p = -2 with the initial valuez0 = 0, z1 = -1.9, z2 = 1.71, z3 = 1.0241, · · · , z30 = -1.1626, z31 = -0.5483, · · · ,

which is now called the

orbit of p = -1.9 with the initial valueFigure 1.0(B). "Turquoise Lion"

Technical Description: The Julia Set of p = (0.281215625, 0.0113825)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Generated by the Mandelbrot Equation

We have used only real numbers for simplicity, but the orbits used in fractal plotting are sequences of complex numbers in the complex plane. Because most of the orbits dance around in the complex plane with time n, it is appropriate to call a collection of orbits a dynamic mathematical system or dynamical system. For example, the Mandelbrot equation (1.1) is a dynamical system consisting of infinitely many orbits of complex numbers, one orbit zn for each choice of values of p and z0. As we shall see, there are infinitely many dynamical systems including the Mandelbrot equation (1.1) and the logistic equation (6.1), each of which generates infinitely many fractals.

Figure 1.1(A). "Circus Seahorses"

Technical Description: The Julia Set of p = (0.03697296, 0.55091235)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Generated by the Dynamical System zn+1 = zn3 + zn + p

Figure 1.1(B). "Circus Elephants"

Technical Description: The Julia Set of p = (0.0641826, 0.5406694)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Generated by the Dynamical System zn+1 = zn3 + zn + p

Canvases: We begin with a simple example. Let R be the rectangle in the complex plane defined by

Let imax = 50, jmax = 32, xmin = -2, xmax = 2, ymin = -1.28 and ymax = 1.28. Then for each

(1.2) Δx = (xmax - xmin) / imax; Δy = (ymax - ymin) / jmax,

(1.3) x = xmin + i Δx; y = ymax - j Δy.

Consequently, we may view R as the rectangle comprising

Plotting the graph of the inequality

Figure 1.2(A) shows two approximations of a fractal called "Goldfish in Love." The one on the left is painted on a canvas with

Figure 1.2(A). "Goldfish in Love" with Different Image Resolutions

Technically, a

canvas can be defined by any positive integers imax and jmax and any real numbers(1.4)

on the input values

Figure 1.2(B). "Jellyfish Queue"

Technical Description: A Subset of the Mandelbrot Set on a p-Canvas

Centered at p = (0.28212284496875, 0.0110092373125)

Generated by the Mandelbrot Equation with z0 = 0

Figure 1.2(C). Mini-Mandelbrot Sets

Technical Description: A Mandelbrot Fractal of z0 = i/√3 on a p-Canvas

Centered at p = (0.00401324, -1.98544205)

Generated by the Dynamical System zn+1 = zn3 + zn + p

The p-Plane, the z-Plane, p-Canvases and z-Canvases: Consider a dynamical system, say, the Mandelbrot equation comprising infinitely many orbits. As we have seen, each orbit is determined by values of p and z0 and interchangeably called the orbit of p with the initial value z0 or the orbit of z0 with the parameter value p. We have also seen that a canvas is a rectangle in the complex plane consisting of pixels

In fractal geometry, we view the complex plane as the set of all complex parameters p and call it the

In Introduction, we mainly talked about the Mandelbrot set and Julia sets generated by the Mandelbrot equation. As we will see, the Mandelbrot set is an object belonging to the

Because a fractal image plotted on a

Figure 1.2(D). "Jady Unicorns"

Technical Description: A Julia Fractal of p = (-0.3959, 0.0312)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (-1.254375, 0.052756)

Generated by the Dynamical System zn+1 = zn4 + zn + p

Figure 1.2(E). "Metallic Unicorns"

Technical Description: A Julia Fractal of p = (-0.39985, 0.02025)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (-1.254375, 0.052756)

Generated by the Dynamical System zn+1 = zn4 + zn + p

Figure 1.2(F). "Gold Elephants"

A Subset of the Julia Set in Figure 7.9(B)

Painted on a z-Canvas with different colors

Figure 1.2(G). "Running Corolla"

Technical Description: The Julia Set of p = (-1.1128, 0.23076)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Generated by the Mandelbrot Equation

Geometric Similarity: We say that two objects in a plane are geometrically similar if one can be obtained from the other by uniform scaling (enlarging or reducing), translation, rotation and/or reflection; see Wikipedia for detail. Geometrically similar objects are said to be congruent if one can be obtained from the other without uniform scaling. We learn the concept of geometric congruence in high school geometry mostly using triangles and conditions like "side-angle-side." In this article, we don't distinguish geometrically similar fractals and treat the images such as the ones shown below to be identical.

Technical Description: See Figure 6.0 in § 6

In geometry, we generally imagine that objects such as triangles are made of a rigid material like a metal plate. If they are made of something totally elastic like pizza dough that can be deformed by kneading then we are in the realm of

topology instead of geometry. Here are some of the basic topological ideas that will appear in the upcoming sections.Topological Ideas: We say that nonempty sets A and B of points in the complex plane are topologically equivalent if there is a continuous function h mapping A onto B in a one-to-one fashion such that its inverse h-1 is also continuous. Such a function h is called a homeomorphism, which is a formal notion of "kneading a pizza dough to change its shape from A to B." For example, a triangle and a square are topologically equivalent or homeomorphic while they are not geometrically similar.

A topological property means a property of a set that is preserved under a homeomorphism. For example, being connected as "one piece" is a topological property because if A and B are homeomorphic and A is connected then B must be connected as well. Similarly, having no holes is a topological property. "Tearing" or "poking a hole" on a pizza dough is not part of "kneading."

To see a few more topological ideas which we will encounter later on, consider a circle in the complex plane. The disk that comprises all of the points inside the circle but none of the points on the circle is called an

open disk. Let A be a set of points in the complex plane and call the set of points not in A the complement of A. Then a point b is called a boundary point of A if every open disk about b contains a point belonging to A and a point belonging to the complement of A. The set of all boundary points of A is called the boundary of A and the largest subset of A without any of its boundary points is called the interior of A.We say that A is

closed if it contains all of its boundary points, and A is open if it contains none of its boundary points. Thus, closed and open sets are generalizations of closed and open intervals on the real number line. We also say that A is bounded if there is a circle in the complex plane that encloses A, and A is compact if A is closed and bounded. Compactness, closedness and openness are all topological properties but boundedness is not.Figure 1.4(B). The Mandelbrot Set

With its Complement (Left Green), Boundary (Left Amber) and Interior (Right)

| Plotted on a p-Canvas by the Divergence Scheme of § 2 | Plotted on a p-Canvas by the Convergence Scheme of § 4 |

As we'll see, the Mandelbrot set generated by the Mandelbrot equation is bounded so its global figure fits in a circle or a rectangle like in

Because the Mandelbrot set is also known to be

closed, its boundary, which coincides with the snowman's silhouette's border, is a part of the Mandelbrot set. It is also known that the boundary has the "topological dimension"As Figure 1.4(B) shows, the filaments are like branched hairs growing outwards from the warty snowman and known to carry infinitely many miniature copies of the snowman, namely mini-Mandelbrot sets. One of them is visible in

Figure 1.4(C). A Local Image of the Mandelbrot Set

With its Complex Boundary Highlighted by the Goldish Color

Painted on p-Canvases Centered at p = (0.281229249, 0.011344208)

See "Daytime View" and "Nighttime View" of a Fractal in § 3

§ 2. The Divergence Scheme

We say that a sequence zn of complex numbers

diverges to ∞ if the real sequenceFigure 2.0(A). A Sample Fractal Generated by the Divergence Scheme

We begin with the

(2.1) zn+1 = fp(zn) = zn2 + p,

one for each p belonging to the

(2.2)

which is the critical point of fp. Because its initial value is the critical point, we call each orbit a

critical orbit of p. ThroughoutWe now have the following surprisingly simple

definition of what NOVA dubbed "the most famous object in modern mathematics." InThe Mandelbrot Set, which we will denote by ℳ, means the set of all parameters p in the

Figure 2.0(B). Another Sample Fractal Generated by the Divergence Scheme

Technical Description: A Local Image of The Mandelbrot Set on a p-Canvas

Centered at p = (0.28212348434375, 0.0110096504375)

If a and b are real numbers, let max{a, b} denote the largest of a and b. To develop our fractal plotting method, we need:

Proposition A: Any orbit zn of p (critical or noncritical) diverges to ∞ if and only if

Proof: Suppose

|zm+1| = |zm2 + p| ≥ |zm|2 - |p| ≥ |zm|2 - |zm| = |zm|(|zm| - 1) = α|zm|,

where α = |zm| - 1 > 1. Since

|zm+2| ≥ |zm+1|(|zm+1| - 1) ≥ α|zm|(|zm| - 1) ≥ α2|zm|.

By induction, it follows that

Proposition B: If |p| > 2, then the critical orbit zn of p diverges to ∞, i.e., p does not belong to the Mandelbrot set ℳ.

Proof: If |p| > 2, (2.1) and (2.2) imply

Hence, by Proposition A, the orbit zn diverges to ∞.

Propositions A with |p| ≤ 2 and Proposition B together imply:

The Divergence Criterion:

Here, we note that if |p| > 2 the divergence criterion is trivial because of Proposition B, and if

We now use the divergence criterion and a computer to

plot the Mandelbrot set ℳ. Let R be a square canvas comprisingWe then regard R as a

The Divergence Scheme: Plotting ℳ on the

· · ·

· · · Thus, the above scheme assigns the color, red or black, to each pixel p in the

We call the plotting process given by the if-statement the divergence scheme, so as to contrast it with the convergence scheme, which we will introduce

Of course, an actual computer program based on the divergence scheme can be streamlined in many ways. Probably the most important is to use

The first of the two images in

Now, simple logic shows that the divergence criterion remains true if we replace

In fact, the accuracy of a computer plot by the divergence scheme depends on the size (or image resolution) of the canvas, the maximum number of iterations M and the threshold θ. The computer plot gets more accurate if any of the three gets greater but with "diminished returns" and with the cost of increasing the computing time. We generally keep the threshold low between 2 and 10 and increase M and the canvas size for a better image. The best way of finding good numbers is to engage in frequent trial-and-error computer experiments. It gets easier quickly as it is similar to figuring out the amount of time needed to cook something in a microwave oven. We generally omit mentioning "approximation," understanding that all computer-generated fractal images are approximations of "real" things.

Coloring Fractals by 24-Bit Colors: Modern computers show graphics in the "24-bit colors" comprising

Important Fact: Figures 2.1(A) and 2.1(B) show that the divergence scheme paints the complement of ℳ while leaving ℳ in a single canvas color like white and black.

Basic Topological Properties of the Mandelbrot Set ℳ:

Zooming In On Local Images: Even though the images in

The question leads to our common practice of

zooming in on a small rectangular neighborhood of a point extremely near or on the boundary of ℳ. Here, the sides of the small rectangle are parallel to the coordinate axes of the complex plane so we can use the rectangle as a canvas with a large number of pixels to magnify the "local" image by the divergence scheme.In fractal art, the boundary of ℳ plays a role of utmost importance for its connection with chaos as described in Introduction.

Example 1: The image shown below on the left is a local image of ℳ given by zooming in on the microscopic square neighborhood of the complex parameter

Figure 2.2. A Local Image of ℳ Generated by the Divergence Scheme

People familiar with multivariable calculus can find a fun project of painting the fractal on a nonplanar surface like a sphere.

Example 2: Figure 2.3 is a cropped and resized image from a computer plot on the large square

The zooming process can be repeated on the local image to capture additional local images. It is time consuming to compute a fractal on such a large canvas, but it gives us an option of finding additional local images as well as an option of making a high resolution printout of the image. For example,

This and That: (1) Here, we show that the zooming process is fairly easy. Use graphic software such as Photoshop and place the mouse cursor on the point on the image like

(2) It is not too hard to generalize the divergence criterion and find a threshold like

Multibrot Set: A Multibrot set is a straightforward extension of the Mandelbrot set given by the Mandelbrot equation (2.1) with 2 replaced by an integer

(2.3) zn+1 = fp(zn) = zn7 + p

with

§ 3. The Mandelbrot Set

In 2008, PBS broadcast a NOVA program proclaiming that the

Mandelbrot set had become "the most famous object in modern mathematics." Since its birth in 1980, the Mandelbrot set, denoted ℳ, popularized fractal plotting by computers and has been the gold standard for all types of fractals. In this section, therefore, we'll discuss some of its notable properties.In § 2, we noted that the divergence scheme paints the complement of ℳ in full color and ℳ itself by a single color like black or white with a cautionary remark that a computer plot is an approximation which is not 100% accurate. We have also seen that ℳ is

closed so it contains its boundary as its subset. As observed throughout in Introduction, the boundary is an extremely important object in fractal art as its complexity and chaotic nature have profound and direct impacts on the structure and aesthetics of the imagery.Because the topological dimension of the boundary is known to

Figure 3.1 shows that the boundary of ℳ in the rectangular area is vividly self-similar, making it a fractal as per our informal definition, and the infinitely recursive self-similarity makes many areas of the boundary look fuzzy and two-dimensional. It is no wonder why nobody knows what the area of the boundary is. Here's a celebrated theorem regarding the boundary of ℳ and the Hausdorff dimension we discussed in Introduction: Shishikura's Theorem (1998): The Hausdorff dimension of the boundary of the Mandelbrot set is 2 (which is the topological dimension of the plane).

As pointed out in Introduction, the theorem effectively proves that no figures on the plane are more complex than the boundary of the Mandelbrot set. Shishikura's theorem also makes the boundary a fractal according to

Mandelbrot's Definition (1975): A fractal means a set for which the Hausdorff dimension strictly exceeds the topological dimension.

For example, the boundary (perimeter) of the Koch Snowflake in

Another Local Image of ℳ and its Boundary (Right)

This is another local image of Figure 2.3.

One of the most important topological properties in fractal geometry is "connectedness" of a set and Figures 2.1(B) and even 3.1 appear to show that the Mandelbrot set ℳ with its complex boundary is "connected" as "one piece." To give precision to the intuitive concept involving "one piece,"

For example, it is known that the "neck" of the "snowman" in Figure 2.1 is the point

The Douady-Hubbard Theorem (1982): The Mandelbrot set is connected.

Adrien Douady and John H. Hubbard also proved that ℳ is "simply connected," which means ℳ has no holes. Topologically speaking therefore, ℳ is well-behaving as a compact set in one piece without a hole. As described by Wikipedia, Douady and Hubbard established many of the fundamental properties of ℳ at an early stage and created the name "Mandelbrot set" in honor of Mandelbrot. They were the pioneers of the mathematical study of ℳ.

"Who Discovered the Mandelbrot Set?" is the title of an interesting read that appeared in Scientific American in 2009. It writes: Douady now says, however, that he and other mathematicians began to think that Mandelbrot took too much credit for work done by others on the set and in related areas of chaos. "He loves to quote himself," Douady says, "and he is very reluctant to quote others who aren't dead."

Note that the two views may appear totally different, mainly because the daytime view shows the

complement of ℳ.Technical Remark: Plotting the complex boundary of ℳ with reasonable accuracy may demand days and weeks of computing time even with a fast modern computer.

| M = 1,500,000 | M = 500,000 |

For the above image on the left, we used whopping 1,500,000 iterations of the Mandelbrot equation for

each black pixel. If we useShown below is a nighttime view of the fractal on the left that reveals the boundary of the mini Mandelbrot set. In

Figure 3.4. The Boundary of the mini-Mandelbrot Set

Connected Components and the Interior of ℳ: In addition to all the wonders of the boundary of ℳ we have witnessed, we'll see in the next section that it is exactly where chaos occurs in ℳ. As mentioned in Introduction, chaos adds unpredictability and irregularity to the imagery and makes it more exciting and creative. So, if we remove the boundary from ℳ, we may think the remainder, namely the interior of the Mandelbrot set, is rather boring. As we will soon find out, that's not the case at all.

We stated earlier a precise definition of a set in the complex plane being "connected" as "one piece" and now wish to dig into the notion of "

pieces." The earlier example shows that the "snowman" of Figure 2.1 cannot be split into "two pieces," the head and body, without having either one of them contain a boundary point of the other.If we restrict our attention to the interior of ℳ which does not contain any of the boundary points, the situation changes completely. Not only can we split the head from the body without worrying about the boundary points, we can actually decompose the snowman into numerous disjoint connected body parts including all those (circular) disks attached to the cardioid body. Note that each of the disks is an open set without a boundary point and it is

maximal in the sense that it is not a proper subset of a larger connected subset of the interior of ℳ.In general, if S is any nonempty set of points in the complex plane, a nonempty maximal connected subset of S is called a

connected component of S. It is an easy task for people familiar with elementary set theory to prove that S can be partitioned into the disjoint union of its connected components. Thus, S is connected if and only if it consists of exactly one connected component (or "piece"). By virtue of the Douady-Hubbard theorem, ℳ has exactly one connected component, but its interior is disconnected and has infinitely many connected components including the aforementioned open disks.Figure 3.5. The Mandelbrot Set

With its Complement (Left Green), Boundary (Left Amber) and Interior (Right)

| Plotted on a p-Canvas by the Divergence Scheme of § 2 | Plotted on a p-Canvas by the Convergence Scheme of § 4 |

In § 4, we will develop our second and last fractal plotting algorithm called the convergence scheme and use it to paint some of the connected components of the interior of ℳ in various colors as shown in the above image on the right. There we will find that the components are subject to fascinating numerical patterns that make the full color painting possible.

The set S is said to be

totally disconnected if it is disconnected and every connected component of S comprises just one point. As we have seen, the topological dimension of a curve is 1, but the topological dimension of a totally disconnected set is 0. In

Here, we have the mini-Mandelbrot set of Figure 3.3 flipped vertically and painted in different colors and its application in multivariable calculus.

§ 4. The Convergence Scheme

The Mandelbrot set has become so illustrious, everybody interested in fractals knows its "warty snowman" shape by heart. To its main cardioid-shaped body, a bunch of (circular) disks are tangentially attached, and to each of these disks another bunch of disks are tangentially attached. The pattern repeats as if the cardioid has children, grandchildren, great grandchildren and so on and so forth. Here, a "cardioid" means, instead of the familiar curve, the curve together with all the points inside the curve.

As Figure 3.1 shows, ℳ also contains infinitely many mini Mandelbrot sets, each of which again comprises a cardioid (which may be distorted) with infinite generations of disks (which may be distorted) and even smaller mini Mandelbrot sets. If we remove the boundary of ℳ from ℳ, we are left with the interior of ℳ comprising the interiors of these disks and cardioids, etc., which are the connected components of the interior of ℳ. Atoms and Molecules: Let's use Mandelbrot's idea shown in his article as a cue and call each connected component of the interior of ℳ an atom of ℳ and a (disjoint) union of one or more atoms a molecule. Thus, atoms include the interiors of all those disks and cardioids with various degrees of distortion and possibly other shapes nobody have encountered yet. An atom and the interior of ℳ are examples of molecules.

As we saw in

Cycles and Periods: A sequence cn of complex numbers is called a cycle if there is a positive integer k satisfying

1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, · · ·

is a

A sequence zn is said to

converge to aconverges to the

Again, suppose ε is a (small) positive real number. Using the aforementioned definition of a

Proposition: Assume that a sequence zn converges to a

The Convergence Scheme: Our new algorithm called the convergence scheme with period index k is based on this proposition and given by replacing the inequality

· · ·

· · · Here, col1, col2, ... , colM are prescribed colors and ε a small positive real number like

For simplicity, let's call a parameter whose critical orbit converges to a

We first apply the divergence scheme with

The first image is generated by the

convergence scheme with period indexThe second image is given by the

convergence scheme with period indicesThe third image is given by a straightforward extension of the scheme described in the preceding paragraph. Because there aren't enough colors that are easily distinguishable, the correspondence between the periods and colors of the atoms is not one-to-one. For example, the atoms of periods

Example 1 shows that the convergence scheme may mean the one with

a single period index or multiple period indices. Note that the convergence scheme with, say, period index 6 cannot distinguish parameters of periodsImportant Conjecture: We have just seen that each of the atoms visible in

An atom (or a connected component) of the interior of ℳ is said to be

hyperbolic, using the technical term in the field of complex dynamics, if the atom has a single period. One of the most important conjectures in fractal geometry, called the density of hyperbolicity, states that every atom is a hyperbolic component and that every parameter on the boundary of ℳ is arbitrarily close to a parameter in a hyperbolic component.We may look at the second part of the conjecture in terms of what we stated in Introduction: Every segment of the boundary of ℳ tangles with infinitely many mini Mandelbrot sets. To see how amazing it is, we should look at the boundary on ℳ depicted in

In this article, we assume that the conjecture is true. For example, it implies that the critical orbit of every parameter in the interior of ℳ converges to a cycle and it resolves the fundamental

weakness of the convergence scheme based on the aforementioned proposition. We now "know" that the hypothesis of the proposition is true in terms of the critical orbits of the parameters in the interior of ℳ, cementing the validity of the convergence scheme.Mini-Mandelbrot Sets: Recall that the last image of

Figure 4.3. Closeups of the Interior of the Mandelbrot Set

The dirt turned out to be well structured molecules, namely mini Mandelbrot sets, which often play important roles in fractal art. Here is a little and nondescript conjecture we have made based on our computer experiments: If

For example, the most visible mini-Mandelbrot set of Figure 4.3 happens to have the base period

Figure 4.4 shows that the boundary of the mini-Mandelbrot set of the base period

Figure 4.4. The the mini-Mandelbrot Set of Base Period

| Compare with the Mandelbrot set of Figure 4.1 |

Chaos in the Mandelbrot Set: In general, an orbit either diverges to ∞ or converges to a cycle, or else it is called a chaotic orbit. As we know, the complement of ℳ comprises the parameters whose critical orbits diverge to ∞. Because of the density of hyperbolicity conjecture, each parameter with chaotic orbit falls into the boundary of ℳ and the orbit of each parameter p near the boundary of ℳ reacts "sensitively" to a minuscule change of the value of p and totally alters its dynamic behavior. In other words, the boundary is exactly where chaos occurs in the Mandelbrot set (provided that the conjecture is true).

In fractal art, the "sensitive dependence on a parameter" near the boundary of ℳ causes the drastic changes of patterns in a nighttime view of the fractal in

The "Eyeball Effect": We have seen that the convergence scheme is valid for painting the interior of ℳ. What happens if we apply it on the complement of

The picture shown below on the left is essentially the same as

Artist's Renderings: As we saw in § 2, any computer generated image of the Mandelbrot set ℳ is an approximation of ℳ, but it is probably more appropriate now to call the image an artist's rendering, as it gets increasingly more colorful and artistic. Here are a couple of artist's renderings of ℳ given by the convergence schemes with different coloring.

Periodicity Diagram: If we label the atoms of the Mandelbrot set in

Figure 4.7. Periodicity Diagram of ℳ

| Note: λ is the period of a mini-Mandelbrot set |

§ 5. Julia Sets and the Fundamental Dichotomy

As mentioned in Introduction, fractals called "Julia sets" preceded the Mandelbrot set by about sixty years and appeared as a part of the work by Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia. To show the main ingredients of their work, we begin with a polynomial function of a complex variable z,

(5.1) f(z) = cm zm + cm-1 zm-1 + · · · + c2 z2 + c1 z + c0,

where m ≥ 2, and cm, cm-1, · · ·, c1, c0 are complex constants with

(5.2) zn+1 = f(zn) = cm znm + cm-1 znm-1 + · · · + c2 zn2 + c1 zn + c0,

consisting of all orbits of z0 belonging to the

Define the

filled-in Julia set of f denoted by 𝒦(f) to be the set of all initial values z0 in the complex plane whose orbits do not divergeJulia and Fatou independently established the following powerful theorem in

The Julia Set of p = (0.26898, 0.004) in color; See Example 1.

Henceforth in this section, we deal exclusively with the Mandelbrot equation with a fixed parameter p comprising all orbits of z0 taken from the

(5.3) zn+1 = fp(zn) = zn2 + p,

which is a special case of (5.2). For simplicity, we now write 𝒦(p) = 𝒦(fp) and 𝒥(p) = 𝒥(fp) and call them the

filled-in Julia set of p and the Julia set of p, respectively. Because the definition of 𝒦(p) is almost identical to the definition of the Mandelbrot set ℳ inExample 1: Choose

As in the case of ℳ, therefore, the image other than "the Cloisonné metal wires" shows the

complement of the filled-in Julia set 𝒦(p), and hence, the critical point of fp at its center does not belong to 𝒦(p). Because it is the only critical point of fp, it follows from the Fatou-Julia theorem that the Julia set 𝒥(p) is a Cantor set.Figure 5.0(B) is given by highlighting the Julia set (the Cloisonné metal wires) in

Just like the boundary of the Mandelbrot set, a Julia set was found to be

chaotic. Its "sensitive dependence on the initial values z0" causes the drastic and unpredictable changes of colors and patterns and makes an image likeExample 2: Choose

Recall that the center of the

It is another fascinating fact about the Mandelbrot set that the period of the parameter p is always reflected in the shape of the filled-in Julia set of p, as in the number of "snake-shaped lion's manes" although why it is so is not completely understood. The image in

| Figure 5.0(C) "Medusa Lion" | Figure 5.0(D) "Medusa Lion" |

| Born from an Atom of Period 10 | Born from an Atom of Period 21 |

The most consequential theorem in fractal geometry is an immediate corollary to the Fatou-Julia theorem and comes from the fact that the base function fp of the Mandelbrot equation (5.3) has exactly one critical point

The Fundamental Dichotomy: For any parameter p in the complex plane, the Julia set of p is either connected or totally disconnected.

For example, the Julia set of Figure 1.1(A) is neither connected nor totally disconnected and the dichotomy assures us that a Julia set like this never arises from the dynamical system (5.3). Mandelbrot, who once studied under Gaston Julia and later became an "IBM fellow," used a computer to visualize the fundamental dichotomy that divides up the complex plane into two parts. He initially defined the Mandelbrot set to be

(†) the set ℳ comprising all parameters p in the complex plane whose Julia sets are connected.

He knew how to compute ℳ as the Fatou-Julia theorem clearly implies that the Julia set of p is connected if and only if the critical orbit of p does not diverge to ∞; see the computer-friendly definition of

Henceforth, we call (†) the

alternative definition of ℳ. It shows that the Julia sets 𝒥(p) of Figures 5.0(C)(D) (and hence the "Medusa Lions" as well) are connected, while "Cloisonné Lion" of| Figure 5.0(E) | "Twin Lions" | Figure 5.0(F) |

Filled-In Julia Sets Born from the Same Atom of Period 17 × 5.

Today the Mandelbrot set ℳ as a "field guide map" is considerably more detailed because of the

periodicity diagram, and all experienced fractal artists know how to use the map and find Julia sets with many of the specific and fascinating shapes. As we have seen, "lions," "elephants" and "seahorses" are among the Julia set shapes.Example 3: Start with an atom of period 17 in ℳ (as a map) between the two atoms used in Example 2. We know what to expect from a Julia set born from the atom of period 17. Then consider a "second generation" atom of Period

The two "lions" are painted by the convergence scheme with period index 85 and the background by the divergence scheme with the threshold

"Esmeralda Lion" is an enlarged version of the filled-in Julia set shown above on the left and "Ruby Lion" shown below is an enlarged version of the filled-in Julia set shown above on the right. The topological structure of a Julia set gets more complex with the period of its generating parameter.

Figure 5.0(G). "Ruby Lion"

The Filled-in Julia Set of

We continue with yet another fascinating attribute of the Mandelbrot set, which is its role as the "field guide map" for finding all types of Julia sets. We have found that the area around the atoms near the cusp of the main cardioid is a "lion sanctuary" where the Julia sets roam disguising "lions" of various shapes. As

An area around the atom of period 4 painted purple and located directly above the cusp of the main cardioid of ℳ in the periodicity diagram is a "

bean field." The image shown below is a Julia set born from that atom. It is interesting to see, through computer experiments, how the "lion shape" gradually changes to the "bean shape" as a parameter moves from the lion territory to the bean territory using the atoms attached to the cardioid as stepping stones.Figure 5.1(A). "Dancing Beans" Born from an Atom of Period 4

The Filled-In Julia Set of p = (0.262, 0.5701) on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

The next three images are from an area around the shoulder of ℳ (as the snowman), which we call "Lerna" of the Mandelbrot set.

Figure 5.2(A). "Hydra of Lerna" Born from an Atom of What Period?

The Filled-in Julia Set of p = (-0.661, 0.3434) on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Figure 5.2(B). "Hydra of Lerna" Born from an Atom of Period 11

The Filled-In Julia Set of p = (0.262, 0.5701) on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Figure 5.2(C). "Hydra's Ash"

The Julia set of p = (-0.6891, 0.27896)

which is near an atom of period 11 but outside of ℳ

Again, if p is near but not in an atom, the Julia set of p still resembles the shape of a Julia set born from the atom as shown in

Example 4 (Jordan Curves): It can be shown that the Julia set of

All other Julia sets

Figure 5.3(A). The Filled-in Julia Set and Julia Set of a Parameter of Period 1

The

Jordan curve theorem states that a Jordan curve divides the plane into two parts, a bounded region called "inside" and an unbounded region called "outside." The theorem seems utterly obvious from a typical image like the one shown above, but the Julia set as a Jordan curve can get extremely convoluted geometrically if the parameter gets arbitrarily close to the boundary of the cardioid. In fact, the proof of the Jordan curve theorem is far from obvious involving algebra, analysis and topology and provides one of the fascinating topics in mathematics.Around the "ear of the snowman" containing the "second generation" atoms of periods

A Filled-in Julia Set Born from an Atom of Period

Many other shapes of Julia sets that can be found on the Mandelbrot set are well documented and shown on the Internet. The locations for the "lion sanctuary," etc. relative to the Mandelbrot set can be translated to the locations relative to any mini Mandelbrot set and provide us with Julia sets often with dazzling backgrounds. The image shown below is a Julia set born in the "hydra territory" of the mini Mandelbrot set in

The Julia Set of p = (0.250003163749637436, -0.000000008959716416)

on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Local Images of (Filled-in) Julia Sets: One of the many wonders of the Mandelbrot set is that it has infinitely many dazzling local images. Not all Julia sets have such a magical power, but we can still dig into many of them to find nice local images. For example, consider the Julia set shown below. Because the Julia set is compact, the global image fits into a rectangle just like in

The Julia Set of p = (0.25000316374967, -0.00000000895972) on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

Shown below is a local image of the Julia set shown above but it is painted by using various colors and the eyeball effect. The eyeball effect makes it easier to identify the numerous "cuttlefish" swimming in the global image. Note that one of the cuttlefish is at the center of the global image.

If we zoom in on the center of the global image between the eyes of the central cuttlefish using different colors but without the eyeball effect, we get another local image of

Local Similarities between Julia sets and the Mandelbrot Set: People with interests in fractal plotting inevitably observe striking resemblance between a local image of the Mandelbrot set and a local image of a Julia set from time to time. For example, if we zoom out from

Recall that the Mandelbrot set and a (filled-in) Julia set belong to two different complex planes, one comprising parameters p and the other initial values z0 of the Mandelbrot equation (1.1). The Mandelbrot set is by definition the set of all parameters p whose critical orbits do not diverge

A parameter p is called a

Misiurewicz point if the critical orbit of p is not a cycle but becomes a cycle after finitely many iterations. For example, while discussing (1.1), we saw that the critical orbit ofz0 = 0, z1 = -2 , z2 = 2 , z3 = 2 , z4 = 2 , · · · .

Because it is not a cycle but becomes a

Some of the known facts are: (1) Misiurewicz points belong to the boundary of the Mandelbrot set. (2) If p is a Misiurewicz point, then the filled-in Julia set of p has no interior points, hence, coincides with the Julia set of p. (3) Misiurewicz points are "dense" in the boundary of the Mandelbrot set, i.e., every open disk about a point on the boundary of the Mandelbrot set contains a Misiurewicz point.

Tan Lei's Theorem (1990): If p is a Misiurewicz point, the Julia set of p centered atAt first glance, the scope of Tan Lei's theorem seems to be rather limited because of the aforementioned properties (1) and (2), but (3) boosts the theorem to be enormously powerful: Let p be a parameter on or near the boundary of the Mandelbrot set. Then it is either a Misiurewicz point or near a Misiurewicz point, and consequently, in a local image of the Mandelbrot set centered at p, we are likely to see a shape resembling the Julia set of p near its center

This probably explains why the local images like Figures

Swimming in the Mandelbrot Set (Left) and in the Julia Set (Right)

§ 6. The Logistic Equation

We have seen so far many wonders of the Mandelbrot set ℳ. Despite the fact that it is generated by a simple quadratic equation

(1.1), it exhibits stunningly intricate and beautiful patterns when visualized. The vibrant and complex visuals of ℳ have inspired artists to seek both abstract and natural art forms and mathematicians to discover hidden theories in fractal geometry and complex dynamics.The boundary of ℳ is self-similar as well as chaotic and has unsurpassed fractal complexity, while the interior of ℳ comprises atoms with astounding geometric and numeric attributes that affect the shapes of the Julia sets in a mysterious way. "Infinite generations" of circular atoms are lined up around the cardioid ofℳ in a miraculous precision and at the same time subject to well-defined numeric patterns given by their periods. Because of its boundary, ℳ is a champion of complexity in mathematics and because of its interior atoms, ℳ and its surrounding area are an ideal "field guide map" showing where to find the Julia sets of varying shapes.

Figure 6.1(A). "Spring Reflection"

A Local Image of the Mandelbrot Set ℳ(0.1) of the Noncritical Point

Generated by the Logistic Equation

Figure 6.1(B). "Bowl and Apple"

Possible Projects for Multivariable Calculus Students

In this section, we discuss the eye-catching simplicity of

(1.1), which may be the most charming feature of the Mandelbrot set. When we paint a fractal, we use a canvas comprising millions of pixels and thousands or even millions of iterations of the dynamical system per pixel. So, adding an extra term in (1.1) can make a significant difference in the computer's runtime. It was especially true at Mandelbrot's time when computers were incomparably slower.Fortunately, it turned out that (1.1) with its simple form is not as constraining in fractal geometry as it first appears. The reason is that if (5.2) is any quadratic dynamical system, then we can use high school algebra to show that it is "conjugate" to (1.1), guaranteeing that any Julia set generated by (5.2) is geometrically similar to a Julia set generated by (1.1) and vice versa. Thus, all Julia sets of (5.2) are essentially the same as Julia sets of (1.1). The

Rather than showing the "conjugacy" in full generality, we will verify it using a special quadratic dynamical system called the

logistic equation. As mentioned in Introduction, the logistic equation became famous with the advent of chaos and is interesting in its own right.

A Local Image of the Mandelbrot Set ℳ(0.1) of the Noncritical Point

Generated by the Logistic Equation

What is the logistic equation? In 1838 Pierre Verhulst introduced a differential equation called the "logistic equation," which became widely used to describe the population dynamics with self-limiting growth. If we replace the derivative in the differential equation by its approximating difference quotient and do some algebra, we get the following "difference equation," which is more suitable for computer applications and again called the logistic equation:

(6.1) zn+1 = fp(zn) = p(1 - zn) zn .

Suppose (6.1) is a dynamical system comprising all functions fp of a complex variable z where p varies through the

We now extend the earlier definition of the Mandelbrot set slightly for convenience. For each orbit zn of (6.1), suppose z0 is its initial value, which may or may not be the critical point of fp. Then we define the Mandelbrot set of z0, denoted by ℳ(z0), to be the set of all parameters p in the

As the standard procedure, let

The origin

As briefly mentioned in

Introduction, biologist Robert May discovered chaotic orbits of p belonging to the intervalThe intersection point of the largest and second largest circular atoms near the right-hand antenna is

A Local Image of the Mandelbrot Set, ℳ(0.2), of the Noncritical Point

Generated by the Logistic Equation

Because of the aforementioned conjugacy and the

Local Images of the Mandelbrot Set, ℳ(0.1), of the Noncritical Point

Generated by the Logistic Equation

Julia Sets by the Logistic Equation: We now show several (filled-in) Julia sets from the Seahorse Bay generated by the logistic equation. The readers should not dismiss these Julia sets citing the aforementioned "conjugacy" and thinking we can find them using the simpler Mandelbrot equation (1.1).

The reason is that finding a certain fractal is, to put it in a nutshell, a chance encounter and nobody can find the parameter p of, say, Figure 6.4(A), from scratch. It means that it is impossible for someone to come up with the Julia set of Figure 6.4(A) using the logistic equation, let alone using the Mandelbrot equation. It is always a good idea to retain our curiosity and try all kinds of venues as we never know when an artistic masterpiece suddenly turns up.

Figure 6.4(A) shows the filled-in Julia set of the parameter

The Filled-In Julia Set of

The Julia Set of

Figure 6.4(C) shows the Julia set of the parameter

The Julia Set of

The parameter

Figure 6.5(A). "Dancing Seahorses"

The Filled-In Julia Set of p = (3.0237615, 0.1) Generated by the Logistic Equation

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0.5, 0)

Figure 6.5(B). "Cloisonné Elephants"

The Julia Set of p = (2.99997742, 0.0100200333) Generated by the Logistic Equation

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0.5, 0)

Conjugacy of the Logistic and Mandelbrot Equations: As indicated at the outset of this section, the logistic equation and the Mandelbrot equation (2.1) are "conjugate" to each other, and hence, by knowing the Julia sets of the Mandelbrot equation, we effectively know all Julia sets of the logistic equation and vice versa. To discuss these ideas in detail, let's rewrite the logistic equation (6.1) as

(6.2) ζn+1 = q(1 - ζn) ζn ,

and reserve zn and p for the Mandelbrot equation

(6.3) zn+1 = zn2 + p ,

where p and

We say that (6.3) is conjugate to (6.2) if there are complex constants

(6.4) zn = a ζn + b,

transforms (6.3) to (6.2) for all n ≥ 0.

Suppose for a moment that (6.3) is conjugate to (6.2) under (6.4) to see what it leads to. Then firstly, (6.4) has its inverse

Secondly, applying the

triangle inequality on the transformation (6.4) and its inverse, it is easy to show that ζn diverges to ∞ if and only if zn diverges to ∞; hence, the transformation (6.4) withIt is not particularly difficult to show that the transformation (6.4) with

Now, without assuming conjugacy, we wish to show that (6.2) can be written in the form

(6.5) a ζn+1 + b = (a ζn + b)2 + p,

which is the result of applying (6.4) on (6.3). Rewrite (6.2) as

-q ζn+1 = q2 ζn2 - q2 ζn ,

i.e., a ζn+1 = (a ζn)2 + 2b(a ζn) ,

where a = -q and b = q/2. Completing the square with respect to

a ζn+1 = (a ζn + b)2 - b2,

which is equivalent to (6.5) with

Since q ≠ 0, it follows that (6.4) is defined by a = -q and b = q/2 and transforms (6.3) to (6.2), as was to be shown, provided (6.6) is true. Summarizing, we have:

Theorem: If p = q(2 - q)/4 then the logistic equation (6.2) and the Mandelbrot equation (6.3) are conjugate to each other and the Julia set of q by (6.2) and the Julia set of p by (6.3) are

(6.6) p = q(2 - q)/4.

As we have seen, the logistic set and the Mandelbrot set generated by (6.2) and (6.3) lie in two different complex planes, the

Between the Logistic Set and the Mandelbrot Set

The corresponding parameters generate geometrically similar Julia sets.

If we solve (7,6) for q by the quadratic formula, we get two

(6.7)

that correspond to a single

Because of the symmetric shape of the logistic set and the two-to-one correspondence shown in Figure 6.7(A), the "

Lion Sanctuary" of the Mandelbrot set located near its cusp corresponds to two "Lion Sanctuaries" of the logistic set, one located above and the other below its center. Similarly, the logistic set actually has four areas that can be called "Seahorse Bays" that correspond to two such areas of the Mandelbrot set near its "neck." Example 2:

The Julia Set of

A rather amazing result coming out of the above computation from (6.2) to (6.6) is another way of writing the logistic equation (6.2), namely,

(6.8) zn+1 = zn2 + p = zn2 + q(2 - q)/4 ; cf. (6.6).

If we plot the Mandelbrot set ℳ(z0) of (6.8) using its critical point

§ 7. Cubic Equations

In the 1990s, personal computer hardware greatly improved for fractal plotting, thanks to the introduction of the Intel Pentium processor, both in terms of computing speed and generating images with higher resolutions and a wider range of colors. As a result, various fractal generating software also became accessible and plotting the Mandelbrot set became so popular that a great many computer hobbyists, digital artists, mathematicians and scientists have explored around it and shown their images on posters, T-shirts, coffee mugs and websites. For a while, almost all calculus textbooks appeared to have images from the Mandelbrot set on their covers.

Although the hidden beauty of the Mandelbrot set is inexhaustible, it has become quite a challenge to unearth attractive local images of the Mandelbrot set or Julia sets that look markedly different from what have been published by using available computers and software. An easy way to find a new pattern such as the ones shown below is to use a dynamical system other than the Mandelbrot equation and there are infinitely many of them.

Figure 7.0(A). "Gold Dragon"

The Connected Julia Set of p = (0.0618974, 0.5400784)

Generated by (7.2) on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

In this section, we consider, as a starting point for a generalization of what we have seen, a simple cubic equation with two critical points and show that even such a simple extension significantly increases the varieties of fractals. At the end of the section, we'll briefly discuss a quartic equation of a similar form with three critical points.

The full generalization of the Mandelbrot and Julia sets entails a

holomorphic function. Holomorphic functions are complex-valued functions of a complex variable which are differentiable on some domains of the complex plane and include familiar functions such as polynomials, rational functions, trigonometric and exponential functions. So, there are endless possibilities we can explore in the quest for new varieties of fractal images.

Figure 7.0(B). "Turquoise Dragon"

The Disconnected Julia Set of p = (0.0371542, 0.5501254)

Generated by (7.2)

on a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0)

In the preceding section, we saw that all quadratic equations are

conjugate to the single and simple Mandelbrot equation (1.1) so they share essentially the same Julia sets. It does not quite work that way for cubic equations but we can still find a relatively simple cubic equation whose critical points can be easily found and which is conjugate to all cubic equations. Consider a general cubic equation:(7.0) ζn+1 = α ζn3 + β ζn2 + γ ζn + δ , with

We wish to show that (7.0) is conjugate to a simpler cubic dynamical system of the form

(7.1) zn+1 = zn3 + r zn + s,

i.e., if there are complex constants

(7.1.1) zn = a ζn + b,

transforms (7.1) to (7.0) for all n ≥ 0. Substituting zn+1 and zn in (7.1) by (7.1.1), multiplying out the right-hand side and solving the result for ζn+1, we get

(7.1.2) ζn+1 = a2ζn3 + 3ab ζn2 + (3 b

Comparison of (7.0) and (7.1.2) followed by careful algebra gives us

(7.1.3) a = √α , b = β/(3√α), r = γ - β2/(3α) and s = √αδ + β(9α - 9αγ + 2β2)/(27α√α),

where √α is any of the two square roots. The first two identities of (7.1.3) show that (7.0) and (7.1) are indeed conjugate to each other. One of the advantages in the reduced formula (7.1) is that finding its critical points and hence plotting its "Mandelbrot set" is easier. The computation illustrates that a similar reduction—or dropping the "second term"—is possible for quartic equations but it requires considerably greater patience.

The Multibrot Sets of (7.1.5) in the

Among all visible atoms, only one is circular and all others are cardioids

... Exact opposite of the Mandelbrot Set

(7.1.4) ζn+1 = ζn3 + q ζn2 + (q2/3) ζn.

Comparing (7.1.4) and (7.0), we get α = 1, β = q, γ = q2/3 and δ = 0. Hence, (7.1.3) implies r = 0 and s = q(9 - q2)/27, and the required conjugate equation is,

(7.1.5) zn+1 = zn3 + p = zn3 + q(9 - q2)/27,

using letter p in place of s. Note that (7.1.5) is a multibrot equation we saw in

Consider now as a more typical example of (7.1), the cubic equation

(7.2) zn+1 = fp(zn) = zn3 + zn + p ,

where the function fp has a conjugate pair of critical points

The comical image shown in

Recall that an

atom means a connected component of the interior ofNotable molecules include the interior of the "Giant," who was speared, and the interior of the "Toddler," who launched the big spear at the Giant, seen near the bottom of

A closeup of the Toddler is shown in

Not surprisingly, local images we find around the boundary of the Toddler are similar to those found near the Mandelbrot set. Here's one of them, which can be used as a night sky of 3D landscapes such as "Mandelbrot Moon" in

The origin (0. 0) of the complex plane is at the tip of the Spearhead, which coincides with the upper left corner of the closeup image shown below. We call the area "Spearhead Bay." Like the Mandelbrot set, the Giant contains infinitely many circular atoms that satisfy the numerical pattern of the periodicity diagram. These circular atoms include the largest and the second largest blue atoms shown in Spearhead Bay, whose periods happened to be

We also note that in Spearhead Bay, the Seaweed grows only on the side of the Giant Mandelbrot Set and tangles with infinitely many extra atoms that look like tropical fish. Interestingly, the fish-like atoms begin to disintegrate near the circular atom of

The boundary of the Giant near the circular atom of

The next image, "Cheetah," is a local image of the Speared Giant painted on a

|

The image shown below is again a local image of the Speared Giant and is painted on a

|

We have noted that ℳ1 contains "irregularities" not seen in the Mandelbrot set from the earlier sections such as the jagged edges of the spearhead. Let

Figure 7.5.

"Atomic Fusion" of the Mandelbrot Sets ℳ1 and ℳ2 of the Two Critical Points.

So, what would be the Mandelbrot set of the dynamical system (7.2) with two critical points?

We first recall that the famed Mandelbrot set ℳ was born as a visualization of the

Fatou-Julia Theorem with a single critical point z0, namely, the Fundamental Dichotomy. For example, suppose p is any constant parameter and 𝒦(p) and 𝒥(p) stand for the filled-in Julia set and the Julia set of p, respectively. Recall that the orbit of z0 with the parameter p is the same as the orbit of p with the initial value z0.Thus, if z0 belongs to 𝒦(p), then the orbit of z0 with the parameter p does not diverge to ∞ and hence, p belongs to ℳ, and similarly, if z0 does not belong to 𝒦(p), then p does not belong to ℳ. Thus, the Fatou-Julia Theorem with a single critical point is equivalent to saying the following in terms of ℳ:

(1) if p belongs to ℳ then 𝒥(p) is connected;

(2) if p belongs to ℳc, then 𝒥(p) is a Cantor set,

where ℳc stands for the complement of ℳ. (1) and (2) are exactly what Mandelbrot intended the Mandelbrot set to satisfy.

Figure 7.6 shows a simplified version of the "Atomic Fusion" in

Note that ℳ1∇ℳ2 happens to be the "symmetric difference" of ℳ1 and ℳ2 but it's just a coincidence for the current case with

two critical points.We now consider the Fatou-Julia Theorem with

two critical points, and suppose z0 is any one of them. Repeating the above argument allows us to conclude that z0 belongs to 𝒦(p) if and only if p belongs to ℳ(z0), namely, the Mandelbrot set of the critical point z0.It is now straightforward to prove that the Fatou-Julia Theorem applied on (7.2) can be written in terms of ℳ1 and ℳ2 as follows:

(1) If p belongs to ℳ1∩ℳ2 then the Julia set of p is connected;

(2) if p belongs to [ℳ1∪ℳ2]c then the Julia set of p is a Cantor set.

(1) and (2) imply:

(3) If the Julia set of p is disconnected but not a Cantor set, then p belongs to ℳ1∇ℳ2.

All of our relevant computer output seems to show that the converse of (3) is true, but the Fatou-Julia Theorem does not confirm it.

Note that if ℳ1 = ℳ2 then (1), (2) and (3) coincide with the earlier (1) and (2). Note also that we have just shown that the "Atomic Fusion" comprising ℳ1∪ℳ2 and ℳ1∩ℳ2 illustrates the Fatou-Julia theorem applied on (7.2) with exactly two critical points. It is natural, therefore, that we call ℳ1∪ℳ2 together with ℳ1∩ℳ2 the

Mandelbrot set of the dynamical system (7.2).In terms of pictures, the fusion diagrams of

both

| p = (0.21828, -0.00230) in [ℳ1∪ℳ2]c | p = (0.2176, 0.0128) in ℳ1∇ℳ2 |

It is hard to tell from the picture if the first "Twin Dragons" is connected but the connectedness is assured by the Fatou-Julia Theorem. Similarly, the second image is a Cantor set. The third image shows a kind that does not appear in the dichotomy theorem, namely a disconnected Julia set which is not a Cantor set.

Example 2: The third image ofThe next two Jula sets are born from one of the molecules that can be also seen near the bottom of Figure 7.6. Note that it intersects with both ℳ1∩ℳ2 (the red zone) and ℳ1∇ℳ2 (the yellow zone).

The connected "Roses" of Figure 7.8(A) is the Julia set of the parameter

The disconnected "Roses" of Figure 7.8(B) shows the Julia set of the parameter

"Elephants" also pop up along with many other shapes in and around the balloon molecule. The next two images show examples of the Julia sets of parameters belonging to [ℳ1∪ℳ2]c near the molecule. They are both Cantor sets.

Figure 7.8(C). "Cantor Elephants"

| p = (0.087, -1.1848) | p = (0.092, -1.1728) |

The image shown below is a Julia set born from the Toddler's cardioid atom of period

Figure 7.9(B). "Flying Lion"

The Julia Set of p = (0.00033, -2.0006785)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0) Generated by (7.2)

Figure 7.10(A). "Pearly Dragon"

The Julia Set of p = (0.0352236, 0.5448064)

On a z-Canvas Centered at z0 = (0, 0) Generated by (7.2)

The Julia set is totally disconnected.

How about a Quartic Equation? Consider the quartic dynamical system

(7.3) zn+1 = fp(zn) = zn4 + zn + p ,

where the function fp now has three critical points

and

The Mandelbrot sets of the three critical points are again superimposed and beautifully

fused together to generate the Mandelbrot set of the dynamical system (7.3) as shown inFigure 7.11(B). The Mandelbrot Set of the Dynamical System (7.3)

It is again easy to show that the

Fatou-Julia Theorem applied on (7.3) can be written in terms of ℳ1, ℳ2 and ℳ3 as follows:

(1) If p belongs to ℳ1∩ℳ2∩ℳ3 then the Julia set of p is connected;

(2) if p belongs to [ℳ1∪ℳ2∪ℳ3]c then the Julia set of p is a Cantor set.

Thus, the second image of Figure 7.11(B) illustrates the historical significance of the Mandelbrot set tied with the Fatou-Julia theorem and the first image the modern role of the Mandelbrot set as a "map" on the complex plane to show where we can find a variety of the Julia sets given by (7.3).

Note that (1) and (2) imply (3): If the Julia set of p is disconnected but not a Cantor set, then p belongs to the difference

ℳ1∇ℳ2∇ℳ3 =

All of our relevant computer output seems to show that the converse of (3) is also true.

| Figure 7.12(A). "Cactus" | Figure 7.12(B). "Clover" |

| The Julia Set of p = (0, 0.111) in | The Julia Set of p = (0, 0) in |

Figure 7.12(C). "Line Dancing Seahorses"

The Julia Set of p = (-0.39985, 0.02025) belonging to ℳ1∇ℳ2∇ℳ3

Figure 7.12(D). "Dancing Seahorses"

A Local Image of the Julia Set of p = (-0.39985, 0.02025) belonging to ℳ1∇ℳ2∇ℳ3

Figure 7.12(E). "Unicorns"

The Julia Set of p = (-0.39674, 0.01012) belonging to [ℳ1∪ℳ2∪ℳ3]c

§ 8. Newton Fractals

The idea of the

Julia set of a polynomial we saw in(8.1) zn+1 = zn - g(zn)/g'(zn),

which generates, like in

As a benefit of using Newton's method, each orbit of (8.1) converges to a root of g quickly more often than not, and it allows us to plot most of the Newton fractals by the convergence scheme (with period index

Furthermore, if we know all the roots of g prior to the fractal plotting, we can modify the convergence scheme fairly easily so as to add more colors to Newton fractals of g; see

g(z) = z n - 1 ,

as its roots r0, r1, r2, ... , rn-1, called the nth roots of unity, are given in a trigonometric expression by

rk = cos(2kπ/n) + i sin(2kπ/n) with r0 = 1.

The fact that each rk is indeed a root of the polynomial g(z) follows immediately from De Moivre's formula.

The image on the left is a Newton fractal for

Thus, there are five basins of attraction in the fractal and they are separated by the

basin boundary. The basin boundary is precisely the Julia set of the Newton fractal and the union of the five basins plays the role of the interior of the filled-in Julia set we saw inThe second image of Figure 8.1 is a variation of the first. The image shown below, called "Crab Queue," is given by zooming in on one of the "bands" in the second image. It is accompanied by a fractal showing the Julia set in "Crab Queue."

g(z) = z 8 + z 7 - z 5 - z 4 - z 3 + z + 1

with the unit disk highlighted. Since g happens to be a factor of

g(z) = z 8 - z 6 + z 4 - z 2 + 1.

Newton's method for finding all roots of g(z) requires us to choose (almost blindly) an intial value z0 to (8.1) hoping it belongs to the basin of attraction to one of the roots, say r1. Once r1 is found, we use the aforementioned Horner's method (aka synthetic division) to divide g(z) by

So, what should we do if we don't know the roots of the input polynomial? One way is to use Muller's Method instead of Newton's method; e.g., see

Wikipedia. Although Muller's Method lacks the simplicity of Newton's method and still requires the "deflating" steps, it works fairly quickly without the burden of finding initial values. All computer programs for the Newton fractals shown in this website use Muller's Method—even for Example 1 whose roots are well known (so we don't have to write down the roots in our computer program).Once our computer program starts running smoothly, plotting Newton fractals provides us with great entertainment. It is easy to pick an input polynomial from infinitely many choices with anticipation from not knowing what to expect in the output. Furthermore, a high-res output image generally emerges within minutes rather than hours and days of runtime.

Here's an example given by a fifth degree polynomial. Just for fun, we painted it on a sphere and a torus as well as on a plane.

Figure 8.3. "Fireflies"

The next example, which is given by a seventh degree polynomial, is painted on a plane and an apple.

Similarly, we have:

Figure 8.6 shows a Newton fractal of a 12th degree polynomial painted on a plane and a sphere. The second image which is painted on a sphere is intended to give a 3D appearance. All of the twelve roots are again found by Muller's Method quickly.

Figure 8.6. "Dragonfly"

Figure 8.7 illustrates two images given by highlighting different parts of essentially the same Newton fractal. We can see from the images that the Newton fractal is generated by a fifth degree polynomial that has two pairs of conjugate complex roots and a simple real root. Each image accompanies a fractal that emphasizes the intricate Julia set.

Figure 8.7. "Ghost Fish" and "Ghost"

Shown below is a fractal similar to the "Ghost" but given by a slightly different fifth degree polynomial. The Julia set appears to be bounded but it is in fact a part of an unbounded Julia set highlighted like the "Ghost."

Shown below are additional Newton fractals.

Newton Fractal on a

Newton Fractal on a

Newton Fractal on a

Newton Fractal on a

Newton Fractal on a

Figure 8.10(C). "Crab Shell"

Newton Fractals on a

Figure 8.10(D). "Barn Owl"

Newton Fractal on a Plane (

Figure 8.11. Newton Fractals of g(z) = (z 5 - 1) / (z 5 + 1)