Anthropic and OpenAI both recently announced “fast mode”: a way to interact with their best coding model at significantly higher speeds.

These two versions of fast mode are very different. Anthropic’s offers up to 2.5x tokens per second (so around 170, up from Opus 4.6’s 65). OpenAI’s offers more than 1000 tokens per second (up from GPT-5.3-Codex’s 65 tokens per second, so 15x). So OpenAI’s fast mode is six times faster than Anthropic’s1.

However, Anthropic’s big advantage is that they’re serving their actual model. When you use their fast mode, you get real Opus 4.6, while when you use OpenAI’s fast mode you get GPT-5.3-Codex-Spark, not the real GPT-5.3-Codex. Spark is indeed much faster, but is a notably less capable model: good enough for many tasks, but it gets confused and messes up tool calls in ways that vanilla GPT-5.3-Codex would never do.

Why the differences? The AI labs aren’t advertising the details of how their fast modes work, but I’m pretty confident it’s something like this: Anthropic’s fast mode is backed by low-batch-size inference, while OpenAI’s fast mode is backed by special monster Cerebras chips. Let me unpack that a bit.

How Anthropic’s fast mode works

The tradeoff at the heart of AI inference economics is batching, because the main bottleneck is memory. GPUs are very fast, but moving data onto a GPU is not. Every inference operation requires copying all the tokens of the user’s prompt2 onto the GPU before inference can start. Batching multiple users up thus increases overall throughput at the cost of making users wait for the batch to be full.

A good analogy is a bus system. If you had zero batching for passengers - if, whenever someone got on a bus, the bus departed immediately - commutes would be much faster for the people who managed to get on a bus. But obviously overall throughput would be much lower, because people would be waiting at the bus stop for hours until they managed to actually get on one.

Anthropic’s fast mode offering is basically a bus pass that guarantees that the bus immediately leaves as soon as you get on. It’s six times the cost, because you’re effectively paying for all the other people who could have got on the bus with you, but it’s way faster3 because you spend zero time waiting for the bus to leave.

edit: I want to thank a reader for emailing me to point out that the “waiting for the bus” cost is really only paid for the first token, so that won’t affect streaming latency (just latency per turn or tool call). It’s thus better to think of the performance impact of batch size being mainly that smaller batches require fewer flops and thus execute more quickly. In my analogy, maybe it’s “lighter buses drive faster”, or something.

Obviously I can’t be fully certain this is right. Maybe they have access to some new ultra-fast compute that they’re running this on, or they’re doing some algorithmic trick nobody else has thought of. But I’m pretty sure this is it. Brand new compute or algorithmic tricks would likely require changes to the model (see below for OpenAI’s system), and “six times more expensive for 2.5x faster” is right in the ballpark for the kind of improvement you’d expect when switching to a low-batch-size regime.

How OpenAI’s fast mode works

OpenAI’s fast mode does not work anything like this. You can tell that simply because they’re introducing a new, worse model for it. There would be absolutely no reason to do that if they were simply tweaking batch sizes. Also, they told us in the announcement blog post exactly what’s backing their fast mode: Cerebras.

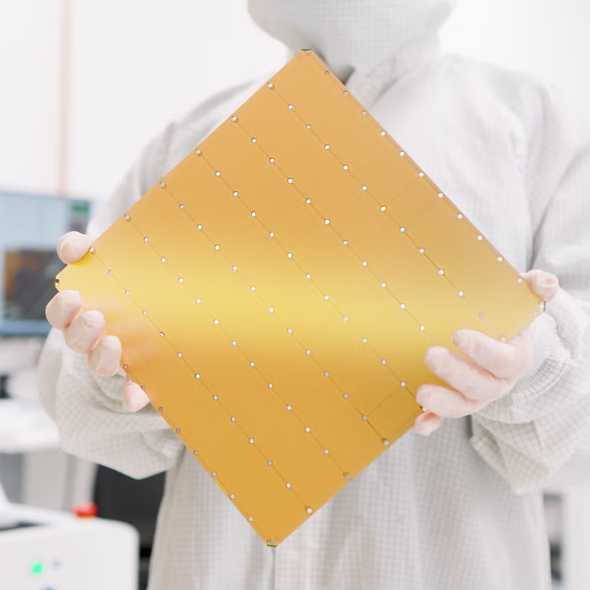

OpenAI announced their Cerebras partnership a month ago in January. What’s Cerebras? They build “ultra low-latency compute”. What this means in practice is that they build giant chips. A H100 chip (fairly close to the frontier of inference chips) is just over a square inch in size. A Cerebras chip is 70 square inches.

You can see from pictures that the Cerebras chip has a grid-and-holes pattern all over it. That’s because silicon wafers this big are supposed to be broken into dozens of chips. Instead, Cerebras etches a giant chip over the entire thing.

The larger the chip, the more internal memory it can have. The idea is to have a chip with SRAM large enough to fit the entire model, so inference can happen entirely in-memory. Typically GPU SRAM is measured in the tens of megabytes. That means that a lot of inference time is spent streaming portions of the model weights from outside of SRAM into the GPU compute4. If you could stream all of that from the (much faster) SRAM, inference would a big speedup: fifteen times faster, as it turns out!

So how much internal memory does the latest Cerebras chip have? 44GB. This puts OpenAI in kind of an awkward position. 44GB is enough to fit a small model (~20B params at fp16, ~40B params at int8 quantization), but clearly not enough to fit GPT-5.3-Codex. That’s why they’re offering a brand new model, and why the Spark model has a bit of “small model smell” to it: it’s a smaller distil of the much larger GPT-5.3-Codex model5.

OpenAI’s version is much more technically impressive

It’s interesting that the two major labs have two very different approaches to building fast AI inference. If I had to guess at a conspiracy theory, it would go something like this:

- OpenAI partner with Cerebras in mid-January, obviously to work on putting an OpenAI model on a fast Cerebras chip

- Anthropic have no similar play available, but they know OpenAI will announce some kind of blazing-fast inference in February, and they want to have something in the news cycle to compete with that

- Anthropic thus hustles to put together the kind of fast inference they can provide: simply lowering the batch size on their existing inference stack

- Anthropic (probably) waits until a few days before OpenAI are done with their much more complex Cerebras implementation to announce it, so it looks like OpenAI copied them

Obviously OpenAI’s achievement here is more technically impressive. Getting a model running on Cerebras chips is not trivial, because they’re so weird. Training a 20B or 40B param distil of GPT-5.3-Codex that is still kind-of-good-enough is not trivial. But I commend Anthropic for finding a sneaky way to get ahead of the announcement that will be largely opaque to non-technical people. It reminds me of OpenAI’s mid-2025 sneaky introduction of the Responses API to help them conceal their reasoning tokens.

Is fast AI inference the next big thing?

Seeing the two major labs put out this feature might make you think that fast AI inference is the new major goal they’re chasing. I don’t think it is. If my theory above is right, Anthropic don’t care that much about fast inference, they just didn’t want to appear behind OpenAI. And OpenAI are mainly just exploring the capabilities of their new Cerebras partnership. It’s still largely an open question what kind of models can fit on these giant chips, how useful those models will be, and if the economics will make any sense.

I personally don’t find “fast, less-capable inference” particularly useful. I’ve been playing around with it in Codex and I don’t like it. The usefulness of AI agents is dominated by how few mistakes they make, not by their raw speed. Buying 6x the speed at the cost of 20% more mistakes is a bad bargain, because most of the user’s time is spent handling mistakes instead of waiting for the model6.

However, it’s certainly possible that fast, less-capable inference becomes a core lower-level primitive in AI systems. Claude Code already uses Haiku for some operations. Maybe OpenAI will end up using Spark in a similar way.

If you liked this post, consider subscribing to email updates about my new posts, or sharing it on Hacker News. Here's a preview of a related post that shares tags with this one.

How does AI impact skill formation?

Two days ago, the Anthropic Fellows program released a paper called How AI Impacts Skill Formation. Like other papers on AI before it, this one is being treated as proof that AI makes you slower and dumber. Does it prove that?

The structure of the paper is sort of similar to the 2025 MIT study Your Brain on ChatGPT. They got a group of people to perform a cognitive task that required learning a new skill: in this case, the Python Trio library. Half of those people were required to use AI and half were forbidden from using it. The researchers then quizzed those people to see how much information they retained about Trio.

Continue reading...