A common component of plastics could come from existing carbon sources

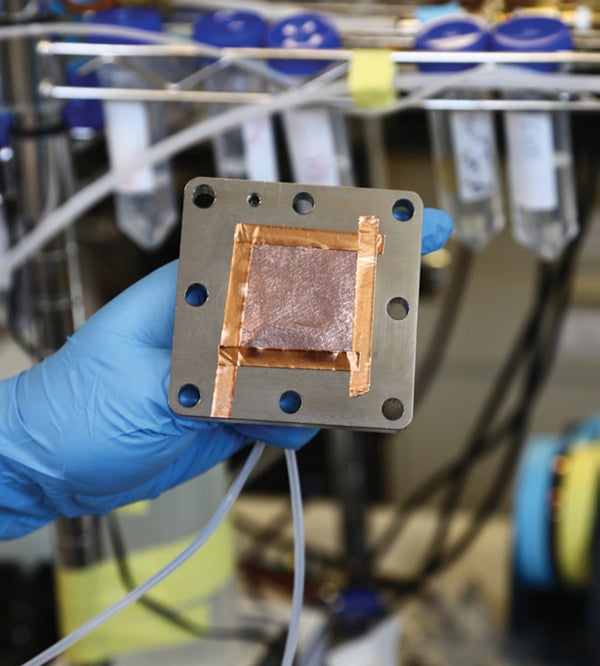

Prototype of a catalyst to make ethylene using CO2

Tyler Irving University of Toronto Engineering

Join Our Community of Science Lovers!

Ethylene is the world's most popular industrial chemical. Consumers and industry demand 150 million tons every year, and most of it goes into countless plastic products, from electronics to textiles. To get ethylene, energy companies crack hydrocarbons from natural gas in a process that requires a lot of heat and energy, contributing to climate change–causing emissions.

Scientists recently made ethylene by combining carbon dioxide gas, water and organic molecules on the surface of a copper catalyst inside an electrolyzer—a device that uses electricity to drive a chemical reaction. The process, described last November online in Nature, could point the way toward using carbon dioxide as feedstock for chemicals and potentially fuels, helping to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and to put a dent in industrial carbon emissions.

The discovery grows out of work published last year by University of Toronto engineer Ted Sargent, describing a similar process that used more electricity and was less efficient overall. So Sargent says he sought out researchers at the California Institute of Technology who are “black belts in molecular design and synthesis.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Caltech chemists Jonas Peters and Theodor Agapie and their colleagues experimented with organic molecules to add to the copper catalyst. An arylpyridinum salt turned out to be the Goldilocks molecule, Sargent says: it formed a water-insoluble film on the copper that positioned the carbon dioxide so its molecules reacted most efficiently with one another, without slowing down the reaction. The result was more ethylene, with fewer by-products such as methane and hydrogen.

Still, the process must become even more efficient before it can be commercially scalable and use carbon scrubbed or captured from facilities such as coal- or gas-burning power plants. Lower energy costs, already occurring with renewable energy sources such as wind, could also help make it more feasible.

“This is a significant breakthrough,” says Randy Cortright, a senior research adviser at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Golden, Colo., who was not involved in the study. This result, he says, is “something that a lot of people are going to pay attention to, and they're going to be able to build on.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can't-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world's best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.