Today there are many models of loudspeakers, produced in different sizes. These models generally use the classic method introduced by Werner von Siemens, founder of Siemens, in the 19th Century. This method consists of coupling a magnet with the movement of a copper coil to vibrate a cone-shaped membrane.

These first two elements are already heavy, space-consuming, and expensive to produce. But they could well be replaced, in addition to the cone-shaped membrane, by a simple dielectric elastomer membrane, and some scientific magic.

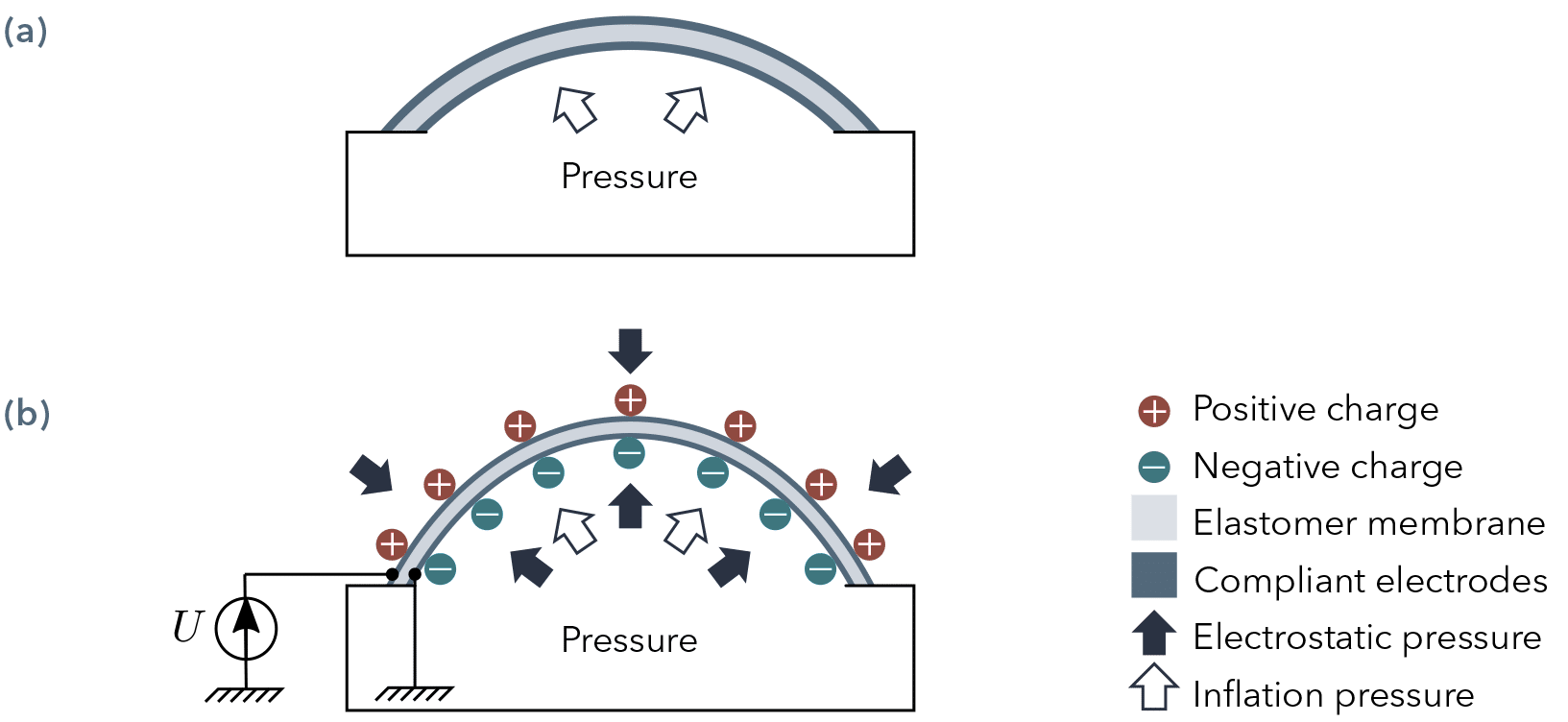

Elastomer, more commonly known as rubber, is an extremely flexible material. Its dielectric properties means that this new membrane conducts very little electrical current. By adding a conductive grease (forming an electrode) to each side of the membrane, a transmitted electrical signal will cause the flexible material to react, causing the vibrations necessary to send sound waves.

This method could make it possible to create a new generation of loudspeakers. Corinne Rouby, a lecturer in mechanics at ENSTA Paris (IP Paris), co-directed Emil Garnell’s thesis with Olivier Doaré, a professor in mechanics, aimed at optimising this new technique23.

Improving the materials used

“To produce a perfect loudspeaker, three criteria must be met: efficiency, spectral balance, and linearity,” explains Olivier Doaré. The aim is to emit as much acoustic energy as possible with as little electrical energy as possible (efficiency). It is also necessary to reproduce the transmitted electrical signal as faithfully as possible in the form of an acoustic wave (spectral balance). And this is true regardless of the desired sound power (linearity).

To produce a perfect loudspeaker, three criteria must be respected: efficiency, spectral balance, and linearity.

Especially since the role of loudspeakers is not necessarily to emit the loudest sound, but rather to remain faithful to the sound it reflects. The choice of a dielectric elastomer membrane could not only lighten the object, but also produce a sound that is just as correct, if a few conditions are met. All this, through a much less expensive production.

“Research interest in dielectric elastomers has been growing since the 2000s4,” states Corinne Rouby. “But the applications were not directly linked to loudspeakers.” However, the characteristics of this type of material quickly placed it in the acoustic domain. “Conventional loudspeakers are heavy and quite expensive to produce. This is due to the use of magnets, which are not necessary,” she says.

The idea of the dielectric elastomer membrane could therefore replace both the coil and the magnet. Lighter in weight, this new design looks promising for the loudspeaker industry, but is still in an experimental phase. “This thesis, although completed, is still intended to enrich the research,” explains the researcher. The next step is in the hands of a post-doctoral chemist whose objective is to improve the coupling between the various materials.

Constraints to overcome

This type of loudspeaker is still only at the experimental stage, and its industrialisation will not be for tomorrow. The results are promising enough to merit further investigation, but they do reveal several constraints that still need to be overcome.

“First, the elastomer membrane is flexible, but also very fragile. Too much voltage can cause an electric arc and make the membrane unusable,” explains Corinne Rouby. This is particularly true for low frequencies, which require a lot of energy to transmit, and which lead to greater movements that make the membrane more fragile.

For this new type of loudspeaker, the researchers worked on the shape to be given to the electrodes (through the conductive grease), to produce any type of frequency. “Each mode of vibration can cause resonances in the object,” explains the researcher. It is therefore necessary to control them so that the speaker does not favour certain frequencies5. Frequency balance can also be achieved by filtering the electrical signal sent to the loudspeaker6.

A major constraint was also identified: “in the laboratory, our loudspeaker was accompanied by a pressure controller that made it possible to manage the various leaks within the cavity. To imagine such a mechanism in a living room is not yet possible,” she concedes. Although this hermetic problem is real, it is a technical constraint that Corinne Rouby does not consider insurmountable.

Once these obstacles have been overcome, this type of loudspeaker can be massively industrialised. Less expensive and lighter, its applications can be dreamed of. Olivier Doaré, co-director of this thesis, is currently working on a similar system for headphones. By using membranes, this time piezoelectric, this scientific advance could soon be in our ears.