Summary: Smart-home devices often serve multiple users with different needs and preferences. Designing for shared use can reduce unnecessary friction and dependency.

Smart-home devices, such as smart cameras, thermostats, and lights, are becoming increasingly ubiquitous, with Horowitz Research and Aviva reporting that nearly half of American households and about 80% of adults in the UK own at least one connected home device. While many of these devices are shared, their design remains mostly centered on a primary-user model and provides limited multi-user support. For example, by default, most devices tie control to a single account owner who can then add additional users and assign various levels of access. This assumption does not accurately reflect the actual use of smart-home technology in households.

To ensure that these devices are readily adopted and cater to people’s needs, designers need to consider how households actually distribute control over shared smart-home technology. Our recent 2-week diary study revealed that this complexity operates on two levels: a device’s location determines who has physical access to it, while a user’s role in the household determines how much control they actually have over the technology.

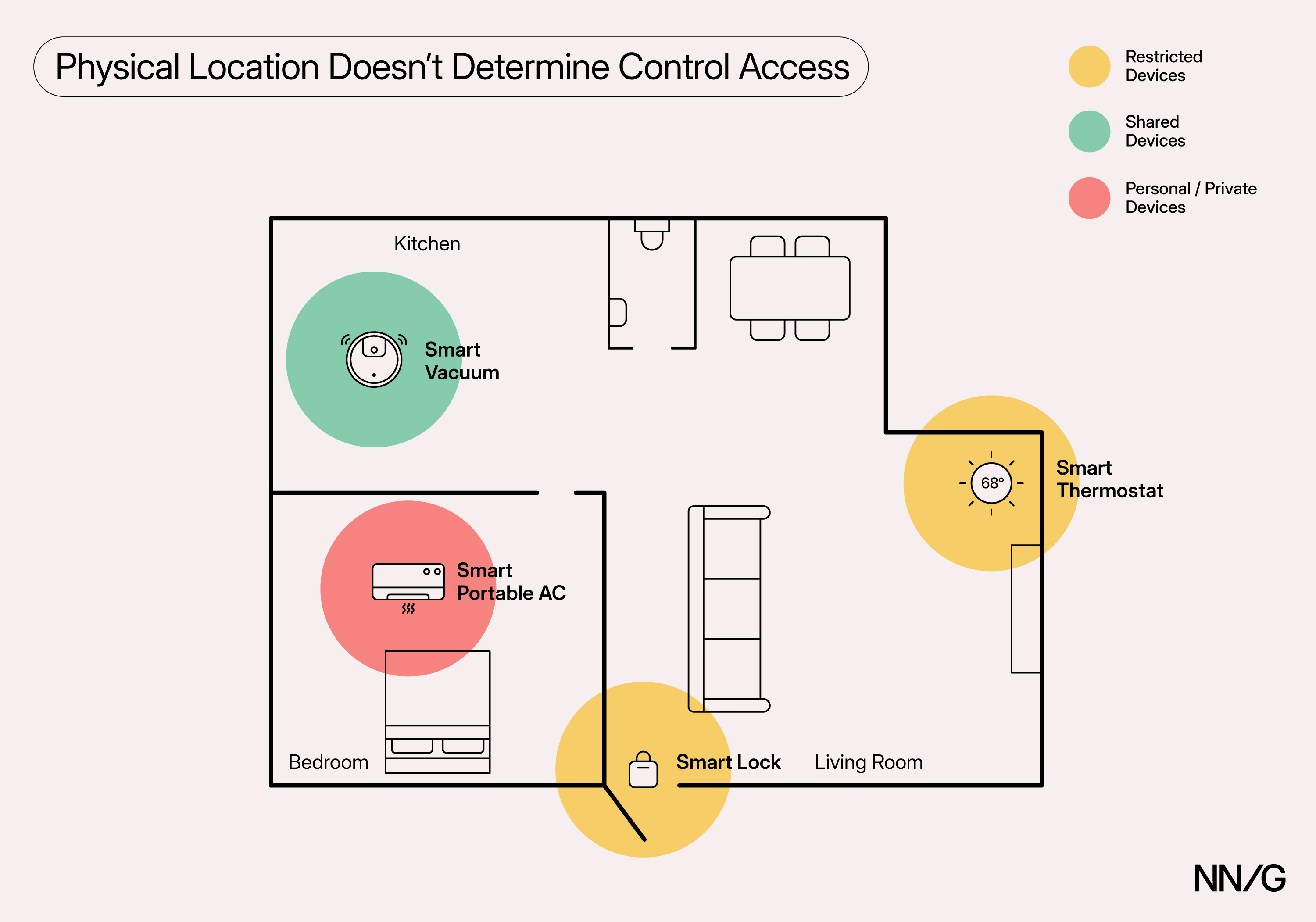

In our study, we saw that in multi-user households, smart technology was often separated into zones of control, where physical location typically determined who could interact with and control the device.

Devices in private zones (e.g., one’s bedroom) were mainly controlled by the room’s occupant(s); those in shared zones (e.g., the living room) could generally be controlled by all household members.

However, control was not determined by location alone. Rules around using certain shared-space devices meant that this technology was restricted for some users, even if they were affected by it or had physical access to it (e.g., parents forbidding children from adjusting the home thermostat).

Hence, shared devices can broadly be separated into two categories: shared or restricted devices.

- Shared devices are located in shared spaces and can be controlled by everyone in the household (e.g., a smart washing machine that the whole household has access to and can use).

- Restricted devices are located in shared spaces, but their use is intentionally restricted to certain household members even if their function affects everyone (e.g., a smart lock that only the adults in the house can control).

These categories are fluid, and devices can shift between them depending on context, household rules, or changing user roles. Understanding how to design for shared devices requires examining not just where devices are located, but who is using them and how different household members navigate varying levels of access and decision-making authority.

Three Types of Smart-Home Users

Our research identified three main user roles based on their level of control access and decision-making power:

- Device manager: the user who usually drives smart device adoption and sets up, configures, and manages shared devices

- Everyday user: the everyday user who mainly controls basic device functionalities

- Restricted user: the largely limited and passive user who is affected by changes in device settings but has little to no control and decision-making authority

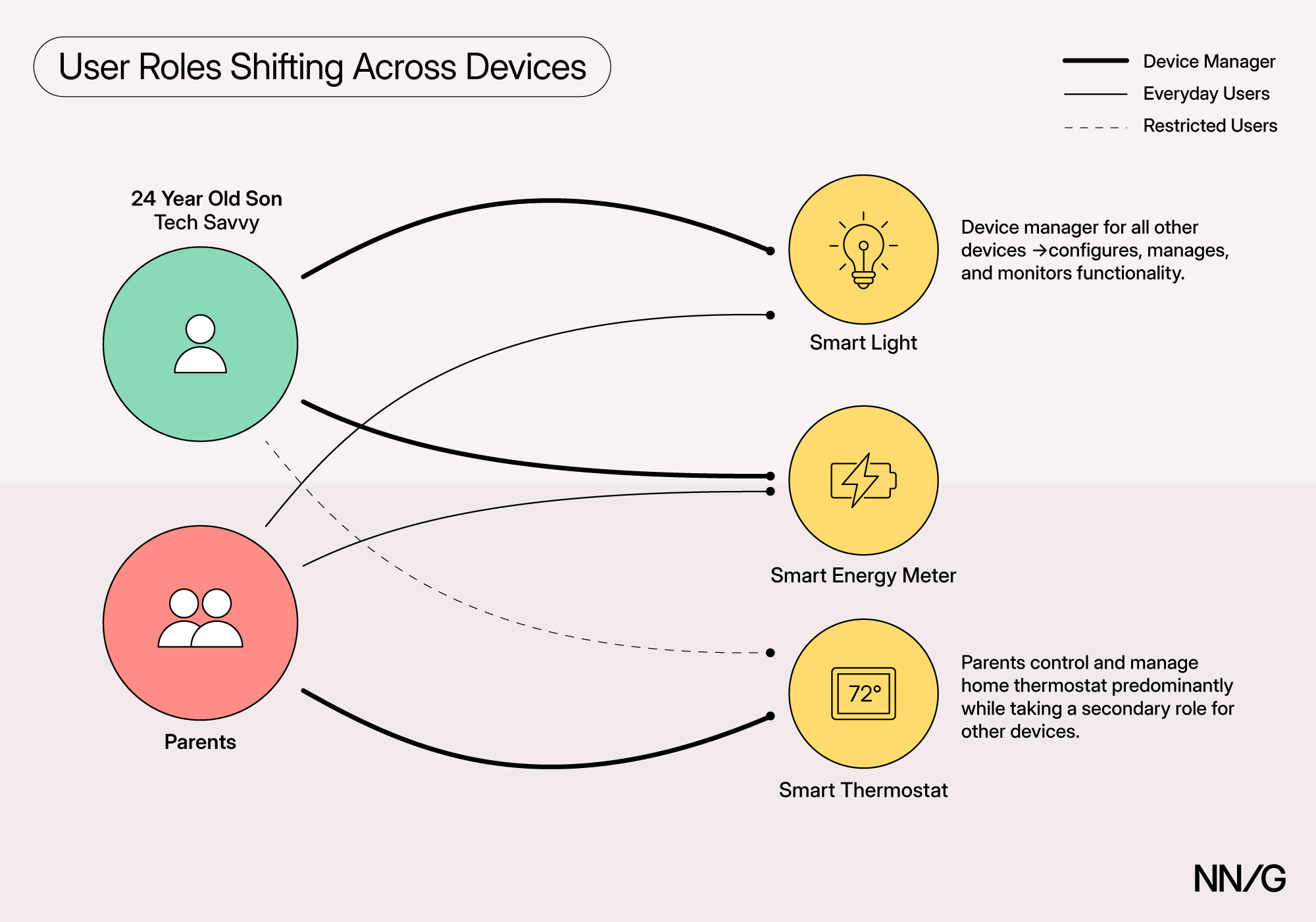

A single household might have different users filling different roles for different devices, and these roles could shift based on context or over time (e.g., a child growing up and getting increased access to control).

Recognizing and understanding these user types, together with their distinct needs and pain points, can help designers support the full smart-home ecosystem, not just the person who sets up and most often configures the devices.

1. Device Managers

Device managers handle setup, configuration, integration, and ongoing maintenance of the household’s smart devices. They value and seek granular control, such as detailed schedules and automations, and thus are the most likely to install manufacturers’ apps for the highest level of control.

Device managers typically make decisions around device control, though, importantly, sometimes they may carry out choices made by others or on behalf of others. For example, multiple participants who were the device managers in their household had to execute actions based on spoken and unspoken preferences. A participant whose partner was working night shifts explained:

“I have to schedule [vacuuming] around people’s sleeping times because our sleeping is opposite, and I don't want to disturb.”

Another device manager, a 24-year-old living with his parents, explained that while he was the one who had pushed for smart-home adoption and handled device setup and configuration because he was more comfortable with technology, he didn’t have decision power over certain devices and settings:

“With the thermostat at home, I actually don't always touch that one. My parents, […] are the ones that use it. And then, if I were to touch it, they’d be yelling at me.”

Hence, device managers are not always the main decision makers and often have to execute actions on behalf of others. This behavior deviates from the typical UX-design assumption that the person using the interface is the one making the decisions; here, the device manager may instead act as a proxy or “translator” between the household needs and the technical implementation.

Device managers typically:

- Drive technology adoption and are more tech-savvy than other users in the home

- Handle setting up and integrating smart devices into the smart-home ecosystem, as well as controlling and adjusting more complex functionalities

- Rely on manufacturers’ apps to control devices, as they provide more granular control

Pain Points of Device Managers

Fragmented Control Across Multiple Interfaces

Device managers often find themselves having to switch between manufacturers’ apps and central hubs, such as Google Home or Alexa, based on their task: manufacturers’ apps for complex actions that require granular control and convenient central hubs for basic actions. Interacting with a device across multiple channels often leads to management overhead and app overload, as the user has to download and access multiple device apps:

“It's nice to have all the devices in one spot rather than having so many different apps on my phone. Which I didn't really want. But because not all the functions are there, on Google, I'm forced to have the different apps.”

“[Central hubs] don't have all the settings. Like in the Alexa app, you can't do all the schedules that I can do in the thermostat app or in the water-heater app. I can't see all the information.”

For households that have multiple devices, the result is a complex and fragmented control system, spanning multiple different interfaces and increasing cognitive load.

Control Burden

Device managers often become the default technical intermediary for the entire household, responsible for both complex automation implementation and simple daily requests. When creating schedules and routines, they must consider everyone's needs, preferences, and potential conflicts, sometimes with incomplete information about what other household members want.

One participant described how she adjusted the thermostat throughout the day, not just for her own comfort, but based on her understanding of what different family members needed:

“I lower [the thermostat] for the baby’s nap so she can sleep. But me and the kids can handle it warmer throughout the day. And then it just cools down when my husband gets home, and then it cools down when the kids start going to bed.”

This burden extends beyond complex tasks: other household members may rely on device managers whenever easy control options are not available, which may create an overwhelming ongoing stream of requests. The result is that device managers carry disproportionate responsibility for both the technical and social coordination of household smart-home technology, which, in turn, leads to additional cognitive strain.

2. Everyday Users

Everyday users interact directly with devices but focus on basic control and rarely adjust advanced settings. They may influence decisions (e.g., suggesting thermostat changes) but typically rely on device managers to carry them out when controls are not straightforward or easily accessible.

Everyday users often favor on-device interfaces, voice commands, or central hubs (e.g., Google Home) over manufacturers’ apps due to their preference for controlling basic functionalities to address immediate needs (e.g., turning a device on or off). These methods provide them with the necessary control while remaining simple and easily accessible.

One device manager described how his parents, as everyday users, rely almost exclusively on Google Home as a central hub to manage basic device functions:

“[My parents control our smart devices] mostly just through Google. They don't have any of the manufacturers’ apps.”

Importantly, even though they prefer more streamlined and simplified control methods, everyday users are still active decision makers who impact household device use.

Everyday users typically:

- Include less tech-savvy adults, older household members, and teenage kids with less decision-making power

- Control basic functionalities, such as turning a device on or off, or changing the thermostat temperature

- Prefer simpler and easy-to-access interfaces, such as central hubs, voice commands, and on-device controls

Pain Points of Everyday Users

Limited Visibility of Device Behavior

When device managers set up automations or schedules for shared devices, everyday users often are not alerted to, and, as a result, don't understand why device behavior is changing or why their manual adjustments get overridden. This creates frustration and confusion, especially when these automated settings conflict with immediate needs:

“When my daughters were here and I was at work, they were changing [the temperature] manually. Then the schedule kept trying to put it back at what I had set it. It was automatically trying to adjust it, and so then they were getting annoyed, so I just turned it off. Because I can't sit there and listen to them text me all day about the air conditioning while I'm trying to work.”

This example shows how lack of automation visibility can disrupt household harmony and force device managers to get rid of complex settings they had carefully worked on. It also demonstrates how overdependency on one user could create frustration for both parties and overburden the person managing the devices.

Reliance on Device Managers

For some devices that require having an app even for basic controls, everyday users had to rely on the device manager to execute simple actions:

“The lamps you can't turn on or off without… You have to use the app for that. So [my husband] will tell me to do that. Most of the time, he physically interacts with the devices. So he'll either interact with the device physically or he'll tell me to handle it.”

While this particular household didn’t encounter many problems with this control distribution, when asked about how her husband is impacted by not having the devices’ apps, the same user explained:

“Well, that's his own fault for not downloading the apps, so that's his natural consequence. If he wants to interact with the devices, he can download the apps.”

Such (over-)reliance on another user can create delays, communication overhead, and inability to control devices when the device manager is not present or otherwise unable to assist.

3. Restricted Users

Restricted users have the most constrained access to smart-home technology, with no or very limited control over devices. Often children or guests, they may be able to use voice commands or on-device controls but don’t have any apps to control or configure smart devices and have little to no decision-making power. Unlike everyday users, they are mostly passive observers and, when they do want to control a device, they often must ask for permission in addition to relying on others to execute actions for them.

Restricted users’ access is also often limited by explicit household rules (e.g., “don’t adjust thermostat”) or physical device restrictions (e.g., a child lock). These constraints highlight that restricted users’ interactions are not only due to ability or interest, but also by enforced boundaries set by others in the household:

“I was busy in the other room and needed to unlock the door for my son to bring a package inside, because he isn't allowed to touch the lock.”

This example illustrates a possible tension in how homes distribute control over devices. While the imposed restriction made sense at the time for this particular household, it could also create dependency and inconvenience for the restricted user, especially when they must interact with these devices on a regular basis.

Restricted users typically:

- Include younger children or guests/temporary visitors

- Have very limited direct interaction with devices and are mostly passive participants

- Don’t have direct access to app-based control but might use voice commands or on-device buttons/interfaces when available

Pain Points of Restricted Users

Restricted users experience intensified versions of everyday users’ challenges, exacerbated by their decreased control access. Like everyday users, they suffer from automation invisibility and have no way to check device status or understand behavioral changes.

However, their complete dependency on others is more severe: they must seek permission even for basic requests and often have no alternative control methods when device managers or everyday users are unavailable.

Design Implications

The interplay between device zones and user roles provides multiple opportunities for improving smart-home design. Moving away from assumptions such as the single-user model can help create experiences with less unnecessary friction, dependency on others, and exclusion.

Enable Deeper Control through Central Hubs

Smart-home developers should enable extended control access by providing open APIs and supporting deeper and more flexible integration with central hubs. In this way, the latter could display the full range of device functionalities and coordinate cross-device behavior intelligently.

Emerging standards like Matter are beginning to address these gaps by defining a shared language and enabling local communication across ecosystems. However, Matter currently covers only core device functions, while more advanced capabilities remain proprietary. The Matter standard lays a strong foundation for openness, but truly granular control still depends on manufacturers’ willingness to expose comprehensive APIs.

While manufacturers may worry that providing more openness might reduce their control over the user experience, from the user’s perspective, it improves usability, reduces friction, and creates a more coherent and adaptive smart-home ecosystem. The rise of tablet-based central smart-home hubs, like Amazon’s Echo Show, Google’s Nest Hub, and soon Apple’s iPad-like hub, points to a trend toward more centralized smart-home control. The larger-screen interfaces of these devices open new possibilities to surface extended controls in a clean, streamlined manner. Combined with participants’ expressed desire for more centralized yet comprehensive control, this seamless and extensive integration could ultimately become a competitive advantage and drive adoption.

Support “Translator” Scenarios

Device managers often execute other people's preferences, yet current systems assume the person using the interface is the main or even sole decision maker. One way to address this discrepancy is to create delegation workflows that help managers systematically capture and implement household members' preferences.

For example, device interfaces could include setup modes that guide device managers through collecting input from different household members, then translate those preferences into schedules or automations. This kind of approach could also incorporate conflict-resolution strategies when preferences clash and decision logs that show who requested what settings, reducing the cognitive burden on device managers coordinating multiple people's needs.

In line with the previous recommendation, these workflows can be incorporated into central hubs (e.g., Google Home, Alexa) or in the increasingly popular, display-based smart home hubs (e.g., Nest Hub, Echo Show) for better visibility. These devices could become collaborative “control centers” where household members can review preferences and temporarily delegate control if needed. Integrating these features at the hub level would make shared decision making more visible and accessible.

Make Automated Behavior and Upcoming Changes Transparent

Devices should proactively alert users when schedules or automations will override their manual adjustments. When someone adjusts a setting directly on the device, the interface should clearly indicate if and when an automation or schedule will modify that setting. This information should appear at the moment of interaction, rather than requiring users to check in the respective device’s app. Devices should also offer simple and immediate resolution options, such as temporarily pausing the schedule or confirming that the manual change should persist. Providing this just-in-time feedback reduces surprise and confusion, helping users maintain a sense of control.

Minimize Unnecessary Friction and Dependency

Reduce scenarios where otherwise capable users have to rely on others for basic controls. In other words, smart home devices must also work “dumb,” when access to a control app is not available. That is, all basic device functions, such as turning a device on/off, should be easily accessible through on-device buttons/interfaces or physical remotes, not just through apps. One would think this guideline is much too obvious, but it’s surprising how many devices don’t follow it.

Support Structured and Collaborative Household-Rule Creation

Smart-home technology can provide dedicated tools to support users in collaboratively negotiating, documenting, and establishing appropriate household rules. Instead of relying on informal restrictions (e.g., verbally imposing a rule for kids to not touch the thermostat) that could lead to confusion and tension, smart-home devices can help formalize rules and make them more transparent. Some example approaches could be rule-creation wizards or rule-impact visualizations that show how restrictions affect different household members and suggest alternatives when policies create significant inconvenience.