On this page:

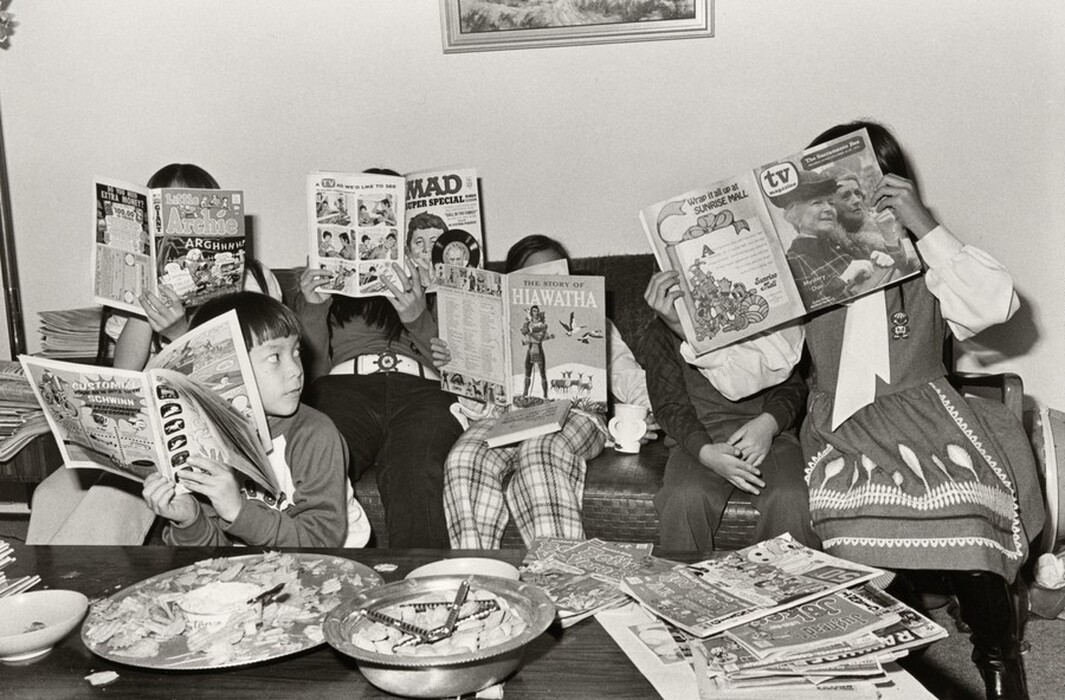

Michael Jang, Study Hall, 1973, gelatin silver print, Charina Endowment Fund, 2022.119.1

In his series The Jangs, Michael Jang photographed family at home. His humorous photographs of their suburban lives expanded the concept of the “all-American” family—the Chinese American Jangs didn’t look like The Brady Bunch.

In Study Hall, Jang’s cousins and aunt sit together on a couch reading comics and a television guide, a messy tray of potato chips and dip on the table in front of them. The covers of decidedly not studious publications block their faces, becoming stand-ins for their portraits.

Jang’s delightful series was almost entirely forgotten. The photographs, which he had first made while a student, sat in a box in the artist’s house for decades while he established a career as a commercial photographer.

In the 2000s, Jang reconsidered this series and shared it with museums, which began adding the photographs to their collections. His photographs took on a new light in the wake of a rise of anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, Jang wheatpasted images from The Jangs on buildings in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

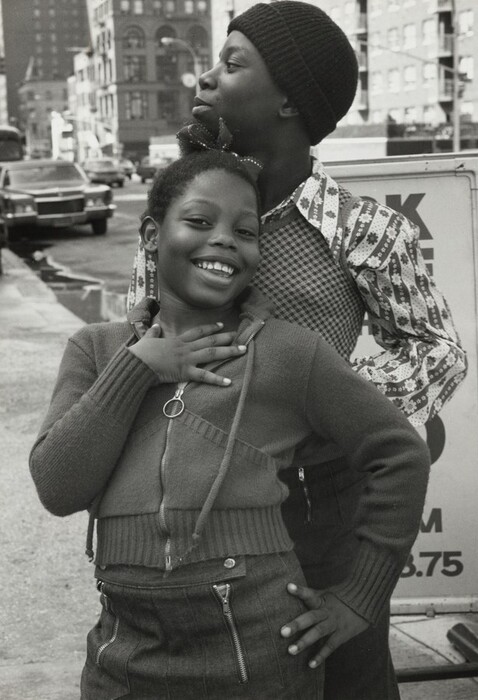

Anthony Barboza, New York City, 1970s, gelatin silver print, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2021.35.4

At a time of inequality and adversity for New York City’s Black community, Anthony Barboza created empowering photographs. Barboza was a founding member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a group of Black photographers formed in the city in 1963. He had arrived there that same year, having never before taken a photograph. Kamoinge, and its influential members like Lou Draper and Roy DeCarava, inspired Barboza to buy a camera and photograph New York.

Barboza was unlike some earlier documentary photographers who sought to create distance or detachment from their subjects. He saw himself as intimately connected to the people on the other side of his lens. “When you take a photograph of someone, you are taking a photograph of you as well. It’s like a mirror. You are feeling them, and they are feeling you.”

Barboza went on to establish a thriving commercial and personal practice focused largely on Black subjects.

Nan Goldin created a visual record of the LGBTQ+ community at a time when it was largely invisible. Her intimate photographs showed her queer and transgender friends going about their daily lives—walking through the park, hanging out at a bar, drinking tea at home. “Completely devoted to my friends, they became my whole world. Part of my worship of them involved photographing them. I wanted to pay homage, to show them how beautiful they were.”

In Goldin’s photographs, her friends live openly and proudly queer lives in an era when there were few safe spaces. Many images, like Christmas at The Other Side, Boston, show her circle at The Other Side, a Boston gay bar.

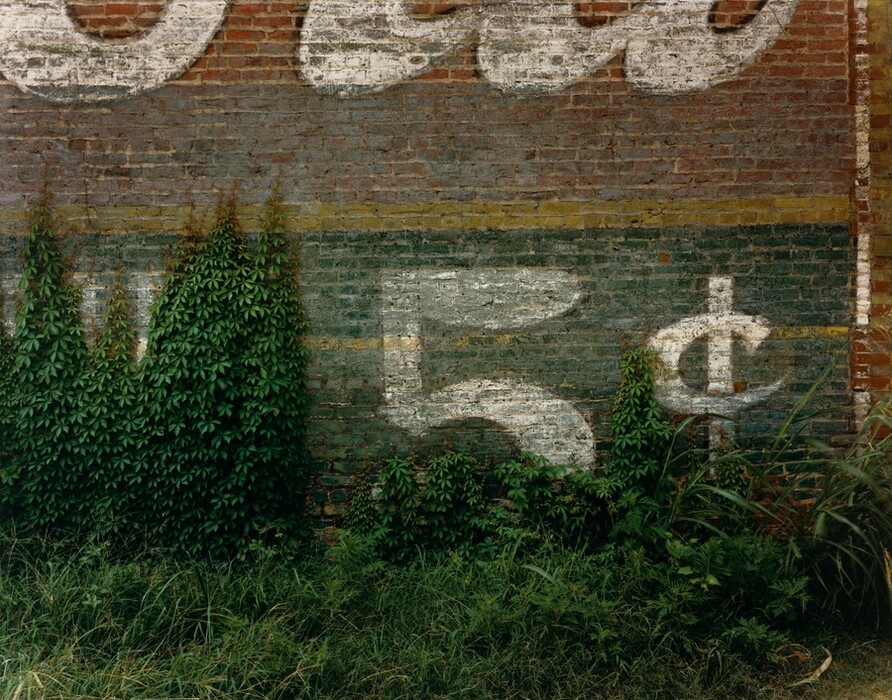

William Christenberry, 5¢, Demopolis, Alabama, 1978, printed c. 2000, chromogenic print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William and Sandra Christenberry), 2015.19.4888

Photographers like William Christenberry adoption of color film transformed documentary photography. While the technology had existed for more than 50 years, “serious” photography had always been black and white. Color prints were regarded as cheap and garish. Christenberry played a crucial role in securing recognition for color photography as an artistic, not just commercial, medium.

His photographs captured the transformation of places, recording their decline, death, and occasional rebirth. Based in Washington, DC, for most of his career, Christenberry visited his native Alabama every year. There, he photographed the changes in the community where he had grown up over time, drawing our eye to everyday beauty we might otherwise overlook.

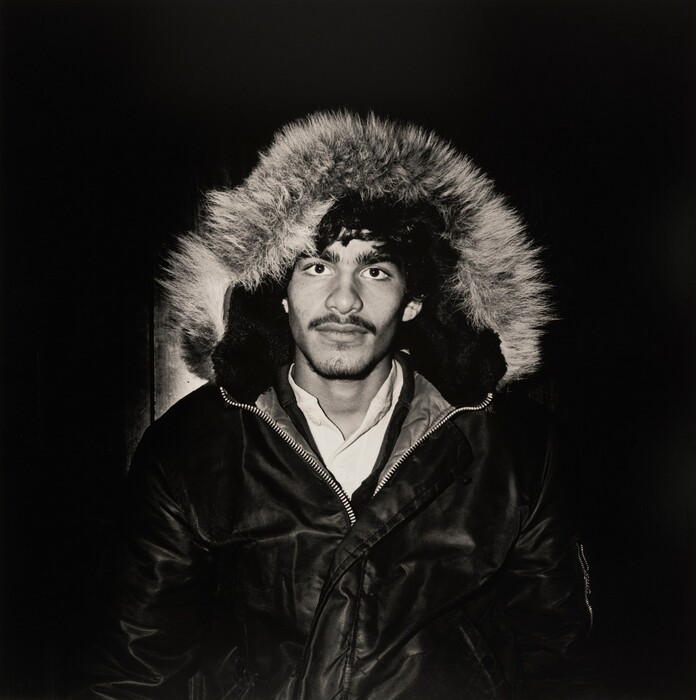

Sophie Rivera, Untitled, c. 1978–1979, printed 2006, gelatin silver print, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2024.8.1

To find sitters for her series of fellow New Yorkers of Puerto Rican heritage (or Nuyoricans), Rivera looked to her Harlem neighborhood. She asked passersby if they were Puerto Rican. If they said yes, she invited them to have their pictures taken in her home. Their grace and dignity reflect the trust between artist and subject.

Rivera’s photographs were innovative not just for her relationship with her subjects, but for her focus on the Puerto Rican or Nuyorican community. Rivera defined herself as “an artist, Latino, and feminist.” She worked against simplistic and negative stereotypes, seeking to make Nuyoricans part of the grand history of American portrait photography. “I have attempted to integrate my cultural heritage into an artistic continuum,” Rivera said.

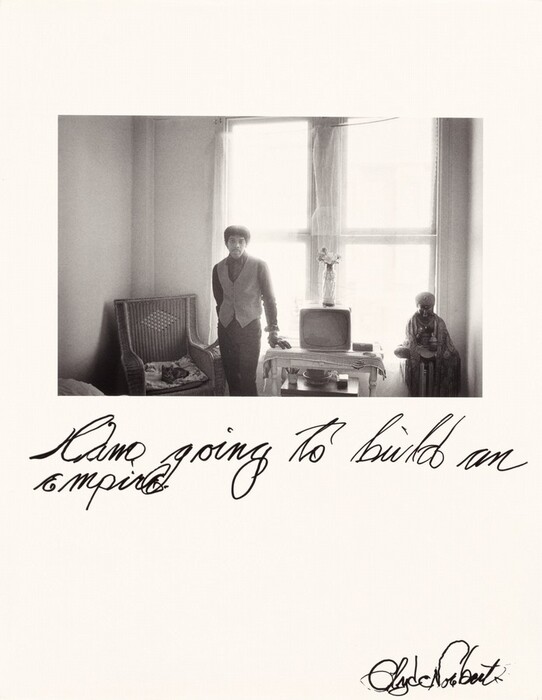

Jim Goldberg, Clyde Norbert, 1978, printed 1984, gelatin silver print, Corcoran Collection (Gift of the Artist), 2015.19.4477

Like Sophie Rivera, Jim Goldberg also explored new ways to engage his subjects. In his series Rich and Poor, Goldberg made portraits of San Franciscans where they lived. He asked his subjects to respond to his pictures by writing directly on them. Goldberg called this collaboration “total documentation,” believing that it “would bring an added dimension, a deeper truth” than a photograph alone.

The series highlighted structural racism as well as the wealth gap. The soaring inflation of the 1970s—(14 percent by the end of the decade) deepened the divide between rich and poor.

Goldberg was optimistic that his works could help effect change, “I believed, I really believed, that once people saw what was happening, then we, as a society, would fix it.” After the ’70s, Goldberg continued to photograph overlooked or neglected groups. His subjects included elderly people in nursing homes, homeless youth, and refugees resettling in Europe.

Equal parts photographer and activist, Espada saw his camera as a tool to advocate for change. His lifelong dedication to both causes was spurred by personal experience: he was arrested and imprisoned for a week after refusing segregated seats on a bus.

For The Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, Frank Espada photographed Puerto Ricans across the country. Portraits such as Mother and Daughter honestly capture the diaspora—and those who returned to Puerto Rico. (Espada himself migrated from Puerto Rico to New York at age 9.) Made between 1970 and 2000, the project includes thousands of photographs of Puerto Ricans in their homes, workplaces, and communities. It spans from Honolulu, Hawaii, to Hartford, Connecticut. Espada also collected more than 100 oral histories. (They are now in the archives of Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.)

Espada also used his photographs to bring awareness to issues like the HIV/AIDS crisis.

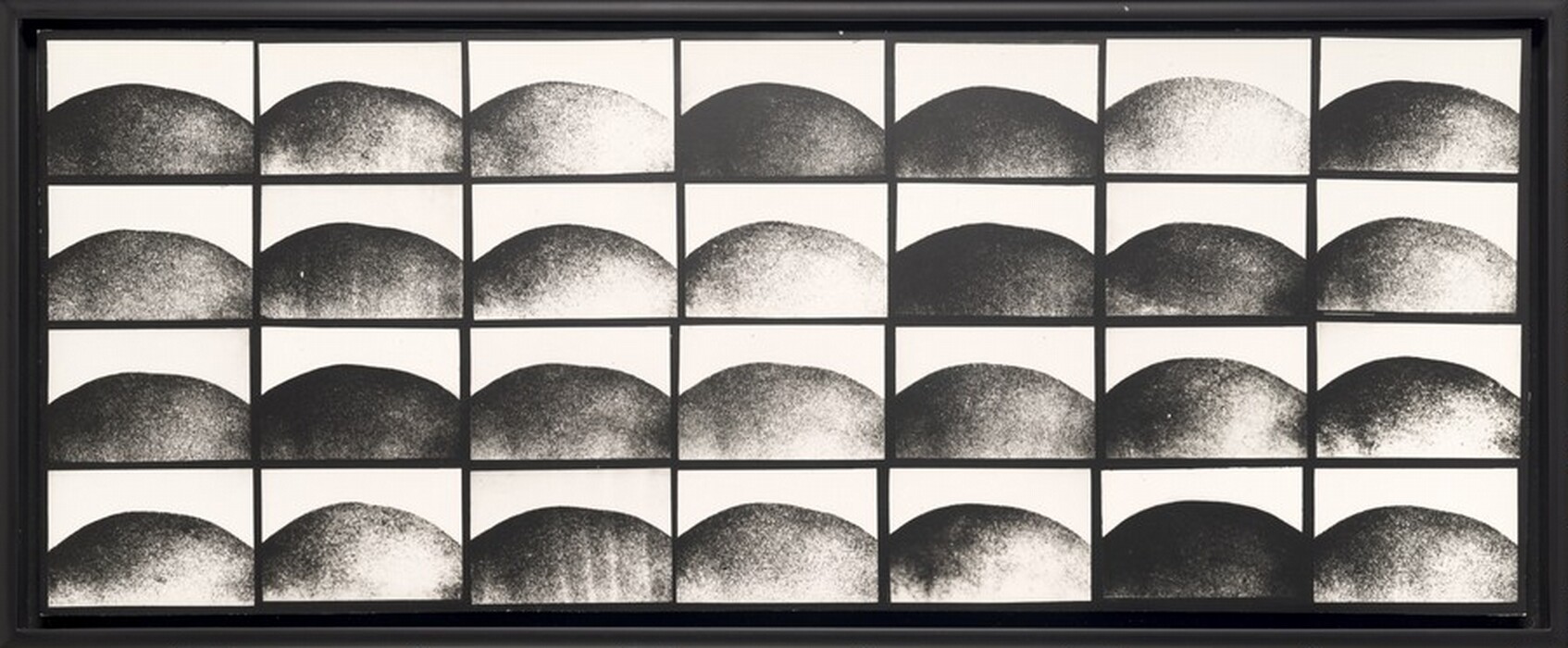

Susan Hiller, Ten Months, 1977–1979, 10 gelatin silver prints and 10 text panels, Gift of the Collectors Committee, Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, Gregory and Aline Gooding Fund, and David Knaus Fund, 2020.76.1.a-t

Documentary photography became central to the practice of many conceptual artists in the 1970s. For some, photographic documents served as the works themselves. For others, the photographs were a way to preserve the artist’s ideas.

Feminist artist Susan Hiller used the camera to reflect on the physical and psychic weight carried during pregnancy. In Ten Months, Hiller makes herself both the subject of her art and the object of her own gaze. Ten framed pictures are each made up of 28 individual photographs—one for each day of the lunar month. These photographs document Hiller’s growing belly over the course of her pregnancy. They are paired with texts from the artist’s journal. In contrast to sentimental notions of pregnancy, these texts criticize women’s unequal position in society.

Documentary photographers of the 1970s often created more holistic pictures of the communities they recorded. No longer detached observers, some photographers of this era ingrained themselves in communities, building trust and understanding. Over the course of her extended visits to South Carolina’s Daufuskie Island between 1977 and 1981, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe developed a bond with the residents. She was able to depict their dignity and joy. She also captured their uncertainty in the face of rapid development on the island.

Located off the southern coast of South Carolina, Daufuskie remained isolated. Its inhabitants, descended directly from enslaved people, had been able to keep their distinct Gullah language and culture. Moutoussamy-Ashe’s photographs became important records of this community—by the time her photographs were published in a book in 1982, the island’s permanent Gullah population had dwindled to 85 residents. Today, that population represents only 2.5 percent of the island’s full-time residents.

A traumatic car accident motivated Marcia Resnick to turn her camera inward. In her series Re-Visions, Resnick staged photographs to explore, with humor and irony, memories of her adolescence. She used models to reenact her imagined youth, blurring the lines between truth and fiction.

In She always read the endings of books before the beginnings., hands with polished fingernails hold down the final pages of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. The right index finger underscores the words “The end.” In another photograph, a woman stands on her head with a book in front of her. The viewer is left to ponder the gap between Resnick’s real childhood and her imagination. In turn, we also consider the accuracy of memory and how photography constructs it.

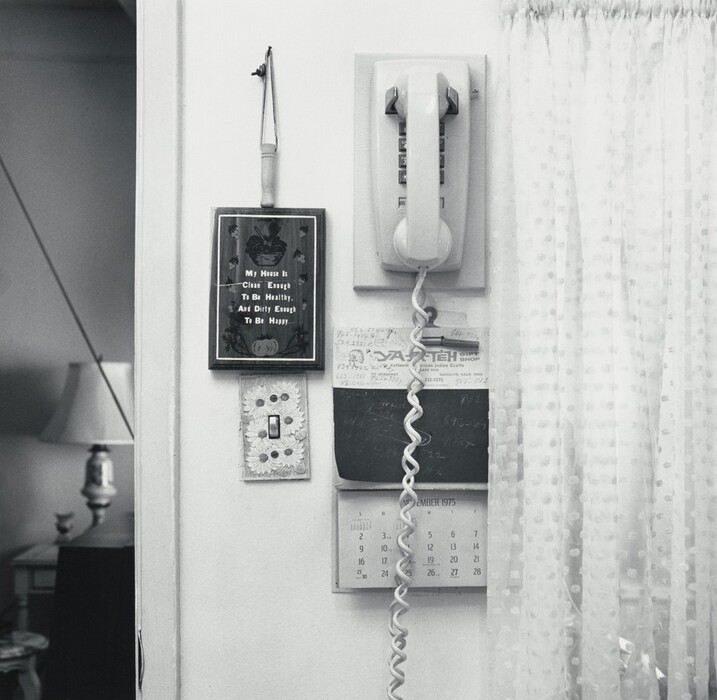

Joanne Leonard, Memo Center with Wall Plaque, c. 1975, gelatin silver print, Gift of the Artist in honor of her daughter, Julia Marjorie Leonard, 2020.117.16

Joanne Leonard has described her narrative-rich scenes of everyday life as “intimate documentary.” She was part of a wave of photographers who examined the social landscape of domestic spaces in the 1970s. The feminist artist recorded parts of the home that were traditionally associated with women and often overlooked. Her goal was “to make everyday life of women a subject of some importance.”

Dotted curtains, a flowered light switch plate, and a humorous wall plaque add a personal touch to this carefully framed picture of a so-called memo center—an area near a wall phone where notes could be jotted down that was popular in 1970s homes. The plaque reads “My house is clean enough to be healthy, and dirty enough to be happy.”

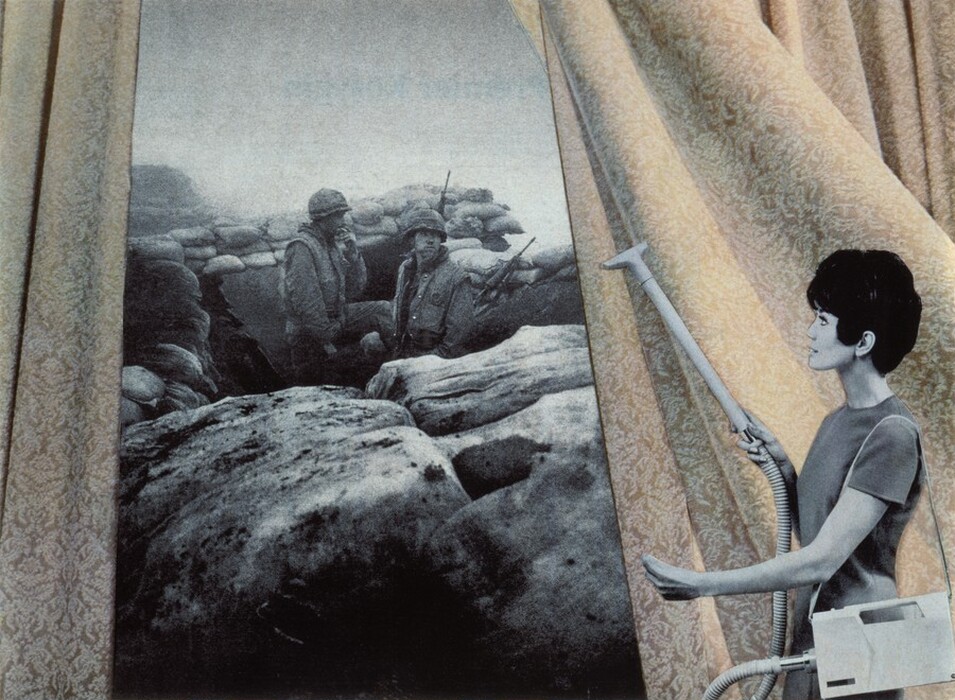

Martha Rosler, Cleaning the Drapes, 1967–1972, printed 2007, inkjet print, Gift of the Collectors Committee and Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2015.76.1

Documentary photographers turned to new subjects in the 1970s, but some continued to draw on the genre’s history of pushing for social change. Photographers like Martha Rosler found new approaches to engaging with politics.

Rosler created photomontages by combining gritty news photographs of the Vietnam War with home-related advertisements culled from glossy women’s magazines. In Cleaning the Drapes she pairs a woman cleaning patterned drapes with two tired soldiers smoking amid rocks and sandbags. Her vacuum wand points to and echoes the soldiers’ rifles. The jolting collision of war imagery and affluent domestic space gives visual form to the description of the conflict as “the living room war”—so called because it appeared on television news nightly.

Rosler distributed photocopies from the series, House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home at anti–Vietnam War demonstrations.