Abstract

I present a personal account of self-organizing systems, framing relevant questions to better understand self-organization, information, complexity, and emergence. With this aim, I start with a notion and examples of self-organizing systems (what?), continue with their properties and related concepts (how?), and close with applications (why?) in physics, chemistry, biology, collective behavior, ecology, communication networks, robotics, artificial intelligence, linguistics, social science, urbanism, philosophy, and engineering.

Similar content being viewed by others

What are self-organizing systems?

"Being ill defined is a feature common to all important concepts.” —Benoît Mandelbrot

I will not attempt to define a “self-organizing system”, as it involves the cybernetic problem of defining “system”1,2,3, the informational problem of defining “organization”4,5, and the ontological problem of defining “self”6. Still, there are plenty of examples of systems that we can usefully call self-organizing: flocks of birds, schools of fish, swarms of insects, herds of cattle, and some crowds of people7,8. In these animal examples, collective behavior is a product of the interactions of individuals, not determined by a leader or an external signal. There are also several examples from non-living systems, such as vortexes, crystallization, self-assembly, and pattern formation in general9,10. In these cases, elements of a system also interact to achieve a global pattern.

Self-organization or similar concepts have been present since antiquity11,12,13,14 (see Section 3.12), so the idea itself is not new. Nevertheless, we still lack the proper conceptual framework to understand it properly. The term “self-organizing system” was coined by W. Ross Ashby15 in the early days of cybernetics2,3,16,17,18,19. Ashby’s purpose was to describe deterministic machines that could change their own organization. Ever since, the concept has been used in a broad range of disciplines20, including statistical mechanics21,22, supramolecular chemistry23, computer science24,25, and artificial life26.

There is an unavoidable subjectivity when speaking about self-organizing systems, as the same system can be described as self-organizing or not27 (see Section 2.1). Stafford Beer28 gave the following example: an ice cream at room temperature will thaw. This will increase its temperature and entropy, so it would be “self-disorganizing”. However, if we focus on the function of an ice cream for being eaten, it would be “self-organizing”, because it would approach a pleasant temperature and consistency for degustating it, improving its “function”. Ashby4 also mentioned that one just needs to call the attractor of a dynamical system “organized”, and then almost any system will be self-organizing.

So, the question should not be whether a system is self-organizing, but rather (being pragmatic) when is it useful to describe a system as self-organizing? The answer will slowly unfold along this paper, but in short, it can be said that self-organization is a useful description when we are interested on describing systems at multiple scales, and understanding how these affect each other. For example, collective motion29 and cyber-physical systems30 can benefit from such a description, compared to a single-scale narrative/model. This is common with complexity31, as interactions can generate novel information that is not present in initial nor boundary conditions, limiting predictability32.

So rather than a definition, we can do with a notion: a system can be described as self-organizing when its elements interact to produce a global function or behavior33. This is in contrast with centralized systems, where a single or few elements “control” the rest, or with simply distributed systems, where a global problem can be divided (reduced) and each element does its part, but there is no need to interact nor integrate elementary solutions. Thus, self-organizing systems are a useful description when we want to relate individual behaviors and interactions to global patterns or functions. If we can describe a system fully (for our particular purposes) at a single scale, then self-organization could be perhaps identified, but superfluos (not useful). And the “self” implies that the “control” comes from within the system, rather than from an external signal/controller that would explicitly indicate elements of what to do.

For example, we can decide to call a society “self-organizing” if we are interested in how individual interactions lead to the formation of fashion, ideologies, opinions, norms, and laws; but at the same time, how the emerging global properties affect the behavior of the individuals. If we were interested in an aggregate property of a population, e.g., its average height, then calling the group of individuals “self-organizing” would not give any extra information, and thus would not be useful.

It should be stressed that self-organization is not a property of systems per se. It is a way of describing systems, i.e., a narrative.

How can self-organizing systems be measured?

"It is the function of science to discover the existence of a general reign of order in nature and to find the causes governing this order. And this refers in equal measure to the relations of man — social and political — and to the entire universe as a whole.” —Dmitri Mendeleev

Even when self-organization had been described intuitively since antiquity — the seeds of the narrative were present — the proper tools for studying it became available only recently: computers34. Since self-organizing systems require the explicit description of elements and interactions, our brains, blackboards, and notebooks are too limited to consider the number of required variables to study the properties of self-organizing systems. It was only through the relatively recent development of information technology that we were able to study the richness of self-organization, just like we were unable to study the microcosmos before microscopes and the macrocosmos before telescopes.

Information

Computation can be generally described as the transformation of information, although Alan Turing35 formally defined computable numbers with the purpose of proving limits of formal systems (in particular, Hilbert’s decision problem). In the same environment where the first digital computers were built in the mid XXth century, Claude Shannon36 defined information to quantify its transmission, showing that information could be reliably transmitted through unreliable communication channels. As it turned out, Shannon’s information H is mathematically equivalent to Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy:

$$H=-K\mathop{\sum}\limits_{i=i}^{n}{p}_{i}\log {p}_{i},$$

(1)

where K is a positive constant and p is the probability of receiving symbol i from a finite alphabet of size n. This dimensionless measure will be maximal for a homogeneous probability distribution, and minimal when only one symbol has a probability p = 1. In binary, we have only two symbols (n = 2), and information would be minimal with a string of only ones or only zeroes (‘1111…’ or ‘0000…’). This implies that having more bits will not tell us anything new, because we already know what the next bits will be (assuming the probability distribution will not change). With a random-like string, such as a sequence of coin flips (‘11010001011011001010…’), information is maximal, because no matter how much previous information we have (full knowledge of the probability distribution), we will not be able to predict what the next bit might be better than chance.

In parallel, Norbert Wiener — one of the founders of cybernetics16,17 — proposed an alternative measure of information, which was basically the same as Shannon’s, but without the minus sign37. Wiener’s information measured what one knows already, so it is minimal when we have a random string (homogeneous probability distribution) because all the information we already have is “useless” (to predict the next symbol), and maximal when we have a single symbol repeating (maximally biased probability distribution), because the information we have allows us to predict exactly the next symbol. Nevertheless, Shannon’s information is the one that everyone has used, and we will do the same.

Shannon’s information is also known as Shannon’s entropy, which can be also used as a measure of “disorder”. We already saw that it is maximal for random strings, and thus minimal for particularly ordered strings. Then, we can use the negative of Shannon’s information (which would be Wiener’s information) as a measure of organization27,37,38. If the organization is a result of internal dynamics, then we can also use this measure for self-organization.

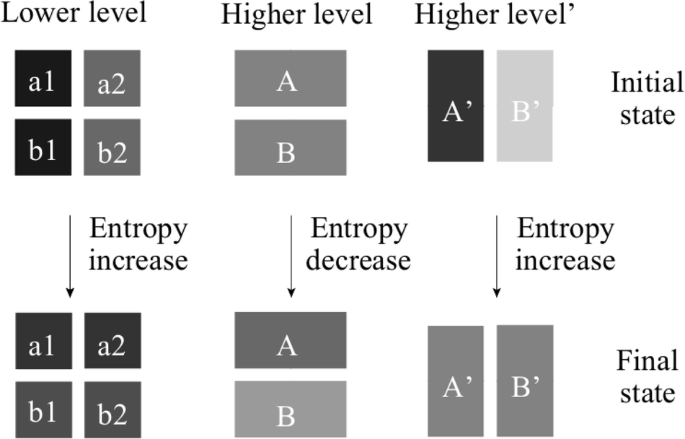

Nevertheless, just like with many measures, the interpretation depends on how the observer performs the measurement. Figure 1 shows how the same system, divided into four microstates or two macrostates (with probabilities represented as shades of gray) can increase its entropy/information (become more homogeneous) or decrease it, depending on how it is observed.

Probabilities of the system being in a state (a1, a2, b1, and b2 at the lower level, which can be aggregated in different ways at a higher level) are represented as shades of gray, so one can observe which configurations are more homogeneous (i.e., with higher entropy): if there is a high contrast in different states (such as between A' and B' in their initial state), then this implies more organization (less entropy), while similar shades (as between A' and B' in their final state) imply less organization (more entropy).

Still, the fact that self-organization is partially subjective does not mean that it cannot be useful. We just have to be aware that a shared description and interpretation should be agreed upon.

Complexity

Self-organizing systems are intimately related to complex systems39,40. Again, the question is not so much whether a system is self-organizing or complex, but when is it useful to describe it as such. This is because most systems can be described as complex or not, depending on our context and purposes.

Etymologically, complexity comes from the Latin plexus, which could be translated as entwined31. We can say that complex systems are those where interactions make it difficult to separate the components and study them in isolation, because of their interdependence32,41. These interactions can generate novel information that limit predictability in an inherent way, as it is not present in initial nor boundary conditions. In other words, there is no shortcut to the future, but we have to go through all intermediate steps, as interactions partially determine the future states of the system.

For example, markets tend to be unpredictable because different agents make decisions depending on what they think other agents will decide42. But since it is not possible to know what everyone will decide in advance, the predictability of markets is rather limited.

Complex systems can be confused with complicated or chaotic systems. Perhaps they will be easier to distinguish considering their opposites: complicated are the opposite of easy, chaotic (sensitive to initial conditions) are the opposite of robust, while complex systems are the opposite of separable.

Given the above notion of self-organizing systems, then all of them would also be complex systems, but not necessarily vice versa. This is because interactions are an essential aspect of self-organizing systems, which would make them complex by definition. However, we could have a description of a complex system whose elements interact but do not produce a global pattern or function we are interested in during the timeframe we are interested in. So, the narrative of complexity would be useful, but not the one of self-organization. Nevertheless, understanding complexity should be essential for the study of self-organization.

Emergence

One of the most relevant and controversial properties of complex systems is emergence43,44,45,46. It could be seen as problematic because last century some people described emergent properties as “surprising”47,48,49. So then emergence would be a measure of our ignorance, and then it would be reduced once we understood the mechanisms behind emergent properties. Also, there are different flavors of emergence, some easier to study and accept than others. But in general, emergence can be described as information that is present at one scale and not at another scale50.

For example, we can have full knowledge of the properties of carbon atoms. But if we focus only on the atoms, i.e. without interactions, we will not be able to know whether they are part of a molecule of graphite, diamond, graphene, buckyballs, etc. (all composed only of carbon atoms) which have drastically different macroscopic properties. Thus, we cannot derive the conductivity, transparency, or density of these materials by looking only at the atomic properties of carbon. The difference lies precisely in how the atoms are organized, i.e. how they interact.

If emergence can be described in terms of information, Shannon’s measure can be used (understanding that we are measuring only the information that is absent from another scale). Thus, emergence would be the opposite of self-organization. This might seem contradictory, as usually emergence and self-organization are both present in complex systems8. But if we take each to its extreme, we can see that maximum emergence (information) occurs when there is (quasi)randomness, so no organization. Maximum (self-)organization occurs when entropy is minimal (no new information, and thus, no emergence). Because of this, complexity can be seen as a balance between emergence and self-organization38.

Why should we use self-organizing systems?

"It is as though a puzzle could be put together simply by shaking its pieces.” —Christian De Duve

Self-organization can be used to build adaptive systems51. This is useful for non-stationary problems, i.e., those that change in time. Since interactions can generate novel information, complexity often leads to non-stationarity. Thus, when a problem changes, the elements of a self-organizing system can adapt through their interactions. Then, designers do not need to specify precisely the problem beforehand, or how it will change, but just to define/regulate interactions to achieve a desired goal33,52,53.

For example, if we want to improve passenger flow in public transportations systems, we cannot really change the elements of the system (passengers). Still, we can change how they interact. In 2016, we successfully implemented such a change to regulate boarding and alighting in Mexico City metro54. In a similar way, we cannot change teachers in an education system. But we can change their interactions to improve learning. We cannot change politicians, but we can regulate their interactions to reduce corruption and improve efficiency. We cannot change businesspeople, but we can control their interactions to promote sustainable economic growth.

There have been many other examples of applications of self-organization55 in different field, and the following is only a partial enumeration.

Physics

The Industrial revolution led to the formalization of thermodynamics in the XIXth century. The second law of thermodynamics states that an isolated system will tend to thermal equilibrium. In other words, it loses organization, as heterogeneities become homogeneous, and entropy is eventually maximized. Still, non-equilibrium thermodynamics has studied how open systems can self-organize56.

Lasers can be seen as self-organized light, which Hermann Haken57,58 used as an inspiration to propose the study of synergetics, which precisely studies self-organization in open systems far from thermodynamic equilibrium and is related to phase transitions59, where criticality is found60.

Self-organized criticality (SOC)61 was proposed to explain why power laws and scale-free-like distributions62,63,64 and fractals65 are so prevalent in nature. SOC was illustrated with the sandpile model, where grains accumulate and lead to avalanches with a scale-free (critical) distribution. Similarly, self-organization has been used to describe granular media66,67.

Generalizing principles of granular media, self-organization can be used to describe and design “optimal” configurations in biological, social, and economic systems68.

Chemistry

Around 1950, Boris P. Belousov was interested in a simplified version of the Krebs cycle. He found that a solution of citric acid in water with acidified bromate and yellow ceric ions produced an oscillating reaction. His attempts to publish his findings were rejected, arguing that it violated the second law of thermodynamics (which only applies to systems at equilibrium, and this system is far from equilibrium). In the 1960s, Anatol M. Zhabotinsky began working on this reaction, and only in the late 1960s and 1970s the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction became known outside the Soviet Union69. Since then, many chemical systems far from equilibrium have been studied70,71. Some have been characterized as self-organizing, because they are able to use free energy to increase their organization72.

More generally, self-organization has been used to describe pattern formation73, which includes self-assembly74.

Molecules are basically atoms joined by covalent bonds. Supramolecular chemistry75 studies chemical structures formed by weaker forces (Van Der Waals, hydrogen bonds, electrostatic charges), and can also be described in terms of self-organization.

Biology

The study of form in biology (morphogenesis) is far from new76, but far from complete77.

Alan Turing78 was one of the first to describe morphogenesis with differential equations. Morphogenesis can be seen as pattern formation with local stimulation and long-range inhibition (skins, scales), or as fractals (capillaries, neurons). These processes are more or less well understood. Still, it becomes more sophisticated for embryogenesis79 and regeneration80, where many open questions remain.

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela proposed autopoiesis (self-production) to describe the emergence of living systems from complex chemistry81,82,83. Autopoiesis can be seen as a special case of self-organization (to the disagreement of Maturana84), because molecules self-organize to produce membranes and metabolism. Moreover, it can be argued that living systems also need information handling, self-replication, and evolvability85.

There are further examples of self-organization in biology7, that include firefly synchronization86, ant foraging87,88, and collective behavior.

Collective Behavior

Groups of agents can produce global patterns or behavior through local interactions. Craig Reynolds presented a simple model of boids89, where agents followed three simple rules: separation (don’t crash), alignment (head to average heading of neighbors), and cohesion (go towards average position of neighbors). Varying its parameters, this simple model produces dynamic patterns similar to those of flocks, schools, herds, and swarms. It was used to animate bats and penguins in the 1992 Batman Returns film and contributed to earning Reynolds an Oscar in 1998.

A flock of boids self-organize even only with the alignment rule and added noise90. It has been shown that when the number of boids increases, novel properties emerge91.

Slightly more sophisticated models have been used to describe more precisely animal collective behavior92,93,94,95.

Furthermore, similar models and rules have been used to study the self-organization of active matter29 and robots (see below).

Ecology

Species self-organize to produce ecological patterns96. These include trophic networks (who eats who)97,98,99, mutualistic networks (cooperating species)100, and host-parasite networks101.

At the biosphere level, ecosystems also self-organize. This is a central aspect of the Gaia hypothesis102,103,104, which defends that our planet self-regulates its own conditions that allow life to thrive.

Self-organization can be useful to study how ecosystems can be robust, resilient, or antifragile105.

Communication networks

Self-organization has been useful in telecommunication networks106, as it is desirable to have the ability to self-reconfigure based on changing demands. Also, having local rules to define global functions makes them robust to potential failures or attacks of central nodes: if there is a path that is not responsive, then an alternative is sought. These principles have been used in Internet protocols, peer-to-peer networks, cellular networks, and more.

Robotics

There has been a broad variety of self-organizing robots107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117, terrestrial, aerial, aquatic, and/or hybrid (for a review see ref. 26).

A common aspect of self-organizing robots is that there is no leader, and the collective function or pattern is the result of local interactions. Some have been inspired in the collective behavior of animals118, and their potential applications are vast.

Artificial Intelligence

As mentioned in the first section of this paper, the study of self-organizing systems originated in cybernetics119,120, which had a strong influence and overlap in the early days of artificial intelligence. Claude Shannon121, William Grey Walter122,123, Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts124,125 contributed to both fields in their early days.

If brains can be described as self-organizing126,127,128, it is no surprise that certain flavors of artificial neural networks have also been described as self-organizing24. Independently on the terminology, adjustments to local weights between artificial neurons lead to an error reduction in the task of the network129.

Even when their interpretation is still controversial130,131,132, large language models have been useful in multiple domains. Whether describing them as self-organizing would bring any benefit or not, still remains to be seen.

Linguistics

The statistical study of linguistics became popular after Zipf133. Different explanations have been put forward to try to explain statistical regularities found across languages134,135,136, and in even more general contexts137.

Naturally, some of these explanations focus on the evolution of language. It has been shown that a shared vocabulary138,139 and grammar140 can evolve using self-organization: individuals interact locally leading to a population converging to a shared language. This is useful not only for understanding language evolution, but also to build adaptive artificial systems. Similar mechanisms can be used in other social systems, e.g. to reach consensus141.

Social Science

Individuals in a society interact in different ways. These interactions can lead to social properties, such as norms, fashions, and expectations. In turn, these social properties can guide, constrain, and promote behaviors and states of individuals.

Computers have allowed the simulation of social systems, including systematic explorations of abstract models142. Combined with an increase in data availability, computational social science143,144 has been increasingly adopted by social scientists. The understanding and implications of self-organization are naturally relevant to this field.

Urbanism

It is similar to the scientific study of cities145,146,147,148,149,150,151.

For example, city growth can be modeled as a self-organizing process152. Similar to the metro case study mentioned above54, self-organization has been shown to efficiently and adaptively coordinate traffic lights153,154,155, and is promising for regulating interactions among autonomous vehicles.

More generally, urban systems tend to be non-stationary, as conditions are changing constantly. Thus, self-organization offers a proven alternative to design urban systems that adapt as fast as their conditions change156.

Philosophy

Concepts similar to self-organization can be traced to ancient Greece in Heraclitus11 and Aristotle157 and also to Buddhist philosophy14.

There has been a long debate about the relationship between mechanistic principles and the purpose of systems. This question was at the origins of cybernetics16. It has been argued12 that self-organization can be used to explain teleology, in accordance with Kant’s attempt from the late XVIIIth century, as purpose can also be described in terms of organization158.

Also, self-organization is related to downward causation159,160,161,162: when higher-level properties cause changes in lower-level elements. This is still debated, along with other philosophical questions related to self-organization32,41.

Engineering

There have been several examples of self-organization applied to different areas of engineering apart from those already mentioned163, such as power grids164, computing25, sensor networks165, supply networks and production systems166, bureaucracies167, and more.

In general, self-organization has been a promising approach to build adaptive systems, as mentioned above. It might seem counterintuitive to speak about controlling self-organization, since we might think that self-organizing systems are difficult to regulate because of a certain autonomy of their components. Still, we can speak about a balance between control and independence, in what has been called “guided self-organization”168,169.

Conclusions

"We can never be right, we can only be sure when we are wrong” —Richard Feynman

There are many open questions related to the scientific study of self-organizing systems. Even when their potential has been promising, they are far from being commonly used to address non-stationary problems. Could it be because of a lack of literacy in concepts related to complex systems? Might there be any conceptual or technical obstacle? Do we need further theories? Independently of the answers, these questions are worth exploring.

For example, we have yet to explore the relationship between self-organization and antifragility170: the property of systems that benefit from perturbations. Self-organization seems to be correlated with antifragility171,172,173, but why or how still has to be investigated. In a similar vein, a systematic exploration of the “slower is faster” effect174 might be useful to better understand self-organizing systems and vice versa.

Many problems and challenges we are facing — climate change, migration, urban growth, social polarization, etc. — are clearly non-stationary. It is not certain that with self-organization we will be able to improve the situation in all of them. But it is almost certain that with the current tools we have, we will not be able to make much more progress (otherwise we would have made it already). It would be imprudent not to make efforts to use the narrative of self-organization, even if for slightly improving situations related to only one of these challenges.

References

von Bertalanffy, L. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller, New York, 1968.

Ross Ashby, W. An Introduction to Cybernetics. Chapman & Hall, London, 1956.

Heylighen, F. and Joslyn, C. Cybernetics and second order cybernetics. In Meyers, R. A. editor, Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, volume 4, pages 155–170. Academic Press, New York, 3rd edition, 2001.

Ashby, W. R. Principles of the self-organizing system. In Foerster, H. V. and Zopf, Jr, G. W. editors, Principles of Self-Organization, pages 255–278. Pergamon, Oxford, 1962.

Rupe, A. & Crutchfield, J. P. On principles of emergent organization. Phys. Rep. 1071, 1–47 (2024).

Gershenson, C. On the Scales of Selves: Information, Life, and Buddhist Philosophy. In Čejková, J., Holler, S., Soros, L., and Witkowski, O., editors, ALIFE 2021: The 2021 Conference on Artificial Life, page 2, Prague, Czech Republic, 07 2021. MIT Press.

Camazine, S. et al. Self-Organization in Biological Systems. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003.

Feltz, B., Crommelinck, M., and Goujon, P. editors. Self-organization and Emergence in Life Sciences, volume 331 of Synthese Library. Springer, 2006.

Ball, P. The self-made tapestry: pattern formation in nature. 1999.

Cross, M. and Greenside, H. Pattern formation and dynamics in nonequilibrium systems. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Kirk, G. S. Natural change in Heraclitus. Mind 60, 35–42 (1951).

Juarrero-Roqué, A. Self-organization: Kant’s concept of teleology and modern chemistry. Rev. Metaphys. 39, 107–135 (1985).

Stengers, I.Généalogies de l’auto-organisation, volume 8 of Cahiers du C.R.E.A. Centre de recherche sur l’épistémologie et l’autonomie, France, 1985.

Gershenson, C. Complexity and Buddhism: Understanding interactions. Buddhism Today 52, 44–48 (2023).

Ashby, W. R. Principles of the self-organizing dynamic system. J. Gen. Psychol. 37, 125–128 (1947).

Rosenblueth, A., Wiener, N. & Bigelow, J. Behavior, purpose and teleology. Philos. Sci. 10, 18–24 (1943).

Wiener, N. Cybernetics; or, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Wiley and Sons, New York, 1948.

Heinz von Foerster. On self-organizing systems and their environments. In Yovitts, M. C. and Cameron, S. editors, Self-Organizing Systems, pages 31–50, New York, 1960. Pergamon.

Saratxaga Arregi, A. Heinz von Foerster’s operational epistemology: orientation for insight into complexity. Kybernetes, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print), 2024/06/28 2024.

Skår, J. and Coveney, P. V. editors. Self-Organization: The Quest for the Origin and Evolution of Structure. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 361(1807), June 2003. Proceedings of the 2002 Nobel Symposium on self-organization.

Wolfram, S. Statistical mechanics of cellular automata. Rev. Mod. Phys. 55, 601–644 (1983).

Crutchfield, J. P. Between order and chaos. Nat. Phys. 8, 17 EP (2011).

Lehn, Jean-Marie Supramolecular chemistry: Where from? where to? Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 2378–2379 (2017).

Kohonen, T. Self-Organizing Maps. Springer, 3rd edition, 2000.

Mamei, M., Menezes, R., Tolksdorf, R. & Zambonelli, F. Case studies for self-organization in computer science. J. Syst. Archit. 52, 443–460 (2006).

Gershenson, C., Trianni, V., Werfel, J. & Sayama, H. Self-organization and artificial life. Artif. Life 26, 391–408 (2020).

Gershenson, C. and Heylighen, F. When can we call a system self-organizing? In Banzhaf, W, Christaller, T., Dittrich, P., Kim, J. T., and Ziegler, J. editors, Advances in Artificial Life, 7th European Conference, ECAL 2003 LNAI 2801, pages 606–614. Springer, Berlin, 2003.

Beer, S. Decision and Control: The Meaning of Operational Research and Management Cybernetics. John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1966.

Vicsek, Tamás & Zafeiris, A. Collective motion. Phys. Rep. 517, 71–140 (2012).

Gershenson, C. Guiding the self-organization of cyber-physical systems. Front. Robot. AI 7, 41 (2020).

De Domenico, M. et al. Complexity explained: A grassroot collaborative initiative to create a set of essential concepts of complex systems. 2019.

Gershenson, C. The implications of interactions for science and philosophy. Found. Sci. 18, 781–790 (2013).

Gershenson, C. Design and Control of Self-organizing Systems. CopIt Arxives, Mexico, 2007. TS0002EN.

Pagels, H. R. The Dreams of Reason: The Computer and the Rise of the Sciences of Complexity. Bantam Books, New York City, NY, USA, 1989.

Turing, A. M. On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 2, 230–265 (1936).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27, 379–423 and 623–656 (1948).

Wiener, N. Cybernetics. Bull. Am. Acad. Arts Sci. 3, 2–4 (1950).

Fernández, N., Maldonado, C., and Gershenson, C. Information measures of complexity, emergence, self-organization, homeostasis, and autopoiesis. In Prokopenko, M. editor, Guided Self-Organization: Inception, volume 9 of Emergence, Complexity and Computation, pages 19–51. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2014.

Bar-Yam, Y. Dynamics of Complex Systems. Studies in Nonlinearity. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, USA, 1997.

Mitchell, M. Complexity: A Guided Tour. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2009.

Heylighen, F., Cilliers, P., and Gershenson, C. Complexity and philosophy. In Bogg, J. and Geyer, R. editors, Complexity, Science and Society, pages 117–134. Radcliffe Publishing, Oxford, 2007.

Farmer, J. D. Making Sense of Chaos: A Better Economics for a Better World. Penguin Random House, London, UK, 2024.

Anderson, P. W. More is different. Science 177, 393–396 (1972).

McLaughlin, B. P. The rise and fall of British emergentism. In Beckerman, Flohr, and Kim, editors, Emergence or reduction? Essays on the prospects of nonreductive physicalism, pages 49–93. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1992.

Bedau, M. A. and Humphreys, P. editors. Emergence: Contemporary readings in philosophy and science. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008.

Prokopenko, M., Boschetti, F. & Ryan, A. J. An information-theoretic primer on complexity, self-organisation and emergence. Complexity 15, 11–28 (2009).

Casti, J. L. Complexification: Explaining a Paradoxical World through the Science of Surprise. Harper Perennial, 1995.

Ronald, E. M. A., Sipper, M. & Capcarrère, M. S. Design, observation, surprise! A test of emergence. Artif. Life 5, 225–239 (1999).

Carroll, S. M. and Parola, A. What emergence can possibly mean. arXiv:2410.15468, 2024.

Gershenson, C. Emergence in Artificial Life. Artif. Life 29, 153–167 (2023).

Frei, R. & Di Marzo Serugendo, G. Advances in complexity engineering. Int. J. Bio-Inspired Comput. 3, 199–212 (2011).

Schweitzer, F. editor. Self-Organization of Complex Structures: From Individual to Collective Dynamics. Gordon and Breach, London, 1997.

Babaoglu, O. et al. Self-star properties in complex information systems: conceptual and practical foundations, volume 3460. Springer, 2005.

Carreón, G., Gershenson, C. & Pineda, L. A. Improving public transportation systems with self-organization: A headway-based model and regulation of passenger alighting and boarding. PLOS ONE 12, 1–20 (2017).

Turcotte, D. L. & Rundle, J. B. Self-organized complexity in the physical, biological, and social sciences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2463–2465 (2002).

Nicolis, G. and Prigogine, I.Self-Organization in Non-Equilibrium Systems: From Dissipative Structures to Order Through Fluctuations. Wiley, Chichester, 1977.

Haken, H. Synergetics and the problem of selforganization. In Roth, G. and Schwegler, H. editors, Self-Organizing Systems: An Interdisciplinary Approach, pages 9–13, New York, 1981. Campus Verlag.

Haken, H. Information and Self-organization: A Macroscopic Approach to Complex Systems. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1988.

Stanley, H. E. Introduction to phase transitions and critical phenomena. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1987.

Sánchez-Puig, F., Zapata, O., Pineda, O. K., Iñiguez, G., and Gershenson, C. Heterogeneity extends criticality. Front. Complex Syst., 1, 2023.

Bak, P., Tang, C. & Wiesenfeld, K. Self-organized criticality: An explanation of the 1/f noise. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381–384 (1987).

Newman, M. E. J. Power laws, Pareto distributions and Zipf’s law. Contemp. Phys. 46, 323–351 (2005).

Caldarelli, G. Scale-Free Networks. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2007.

Clauset, A., Shalizi, CosmaRohilla & Newman, MarkE. J. Power-law distributions in empirical data. SIAM Rev. 51, 661–703 (2009).

Mandelbrot, Benoît The fractal geometry of nature. WH Freeman, 1982.

Török, J., Krishnamurthy, S., Kertész, J. & Roux, S. Self-organization, localization of shear bands, and aging in loose granular materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 3851–3854 (2000).

Jain, N., Khakhar, D. V., Lueptow, R. M. & Ottino, J. M. Self-organization in granular slurries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3771–3774 (2001).

Helbing, D. & Vicsek, Tamás Optimal self-organization. N. J. Phys. 1, 13.1–13.17 (1999).

Winfree, A. T. The prehistory of the belousov-zhabotinsky oscillator. J. Chem. Educ. 61, 661 (1984).

Kondepudi, D. and Prigogine, I. Modern thermodynamics: from heat engines to dissipative structures. John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Knoll, P., Ouyang, B. & Steinbock, O. Patterns lead the way to far-from-equilibrium materials. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 4, 19–30 (2024).

Vanag, V. K. & Epstein, I. R. Pattern formation in a tunable medium: The Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction in an aerosol ot microemulsion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 228301 (2001).

Cross, M. C. & Hohenberg, P. C. Pattern formation outside of equilibrium. Rev. Mod. Phys. 65, 851–1112 (1993).

Whitesides, G. M. & Grzybowski, B. Self-assembly at all scales. Science 295, 2418–2421 (2002).

Lehn, Jean-Marie Perspectives in supramolecular chemistry—from molecular recognition towards molecular information processing and self-organization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 29, 1304–1319 (1990).

Thompson, D’Arcy WentworthON GROWTH AND FORM. Cambridge University Press, 1917.

Davies, J. A. Mechanisms of morphogenesis. Elsevier, 2023.

Turing, A. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B, Biol. Sci. 237, 37–72 (1952).

Levin, M. Left–right asymmetry in embryonic development: a comprehensive review. Mech. Dev. 122, 3–25 (2005).

Levin, M. Large-scale biophysics: ion flows and regeneration. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 261–270 (2007).

Varela, F. J., Maturana, H. R. & Uribe, R. Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model. Biosystems 5, 187–196 (1974).

Maturana, H. and Varela, F.Autopoiesis and Cognition: The realization of living. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht, 1980.

Gershenson, C. Requisite variety, autopoiesis, and self-organization. Kybernetes 44, 866–873 (2015).

Maturana, H. Everything is said by an observer. In Thompson, William Irwin editor, Gaia, a Way of Knowing: Political Implications of the New Biology, pages 65–82. Lindisfarne Press, Great Barrington, MA, USA, 1987.

Muñuzuri, A. P. & Pérez-Mercader, J. Unified representation of life’s basic properties by a 3-species stochastic cubic autocatalytic reaction-diffusion system of equations. Phys. Life Rev. 41, 64–83 (2022).

Strogatz, S. Sync: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order. Hyperion, 2003.

Aron, S., Deneubourg, J. L., Goss, S., and Pasteels, J. M. Functional self-organization illustrated by inter-nest traffic in ants: The case of the argentinian ant. In Alt, W. and Hoffman, G. editors, Biological Motion, volume 89 of Lecture Notes in BioMathematics, pages 533–547. Springer, Berlin, 1990.

Theraulaz, G. & Bonabeau, E. A brief history of stimergy. Artif. Life 5, 97–116 (1999).

Reynolds, C. W. Flocks, herds, and schools: A distributed behavioral model. Comput. Graph. 21, 25–34 (1987).

Vicsek, Tamás, Czirók, András, Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I. & Shochet, O. Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 1226–1229 (1995).

Ikegami, T., Mototake, Yoh-ichi, Kobori, S., Oka, M. & Hashimoto, Y. Life as an emergent phenomenon: studies from a large-scale boid simulation and web data. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 375, 20160351 (2017).

Couzin, I. D. et al. Self-organization and collective behavior in vertebrates. In Slater, Peter J. B., Rosenblatt, J. S., Snowdon, C. T., and Roper, T. J. editors, Advances in the Study of Behavior, volume 32, pages 1–73. Academic Press, San Diego, CA, USA, 2003.

Couzin, I. D., Krause, J., Franks, N. R. & Levin, S. A. Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move. Nature 433, 513–516 (2004).

Buhl, C. et al. From disorder to order in marching locusts. Science 312, 1402–1406 (2006).

Ballerini, M. et al. Interaction ruling animal collective behavior depends on topological rather than metric distance: Evidence from a field study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 1232–1237 (2008).

Levin, S. A. Self-organization and the emergence of complexity in ecological systems. AIBS Bull. 55, 1075–1079 (2005).

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese, R. & Torres, F. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279, 860–863 (1998).

Goodnight, C. et al. Evolution in spatial predator–prey models and the “prudent predator”: The inadequacy of steady-state organism fitness and the concept of individual and group selection. Complexity 13, 23–44 (2008).

Sahasrabudhe, S. & Motter, A. E. Rescuing ecosystems from extinction cascades through compensatory perturbations. Nat. Commun. 2, 170 (2011).

Saavedra, S., Stouffer, D. B., Uzzi, B. & Bascompte, J. Strong contributors to network persistence are the most vulnerable to extinction. Nature 478, 233–235 (2011).

Runghen, R., Poulin, R., Monlleó-Borrull, C. & Llopis-Belenguer, C. Network analysis: Ten years shining light on host–parasite interactions. Trends Parasitol. 37, 445–455 (2021).

Lovelock, J. E. & Margulis, L. Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the gaia hypothesis. Tellus 26, 2–10 (1974).

Lenton, T. M. and Williams, Hywel T. P. Gaia and evolution. In Crist, E. and Rinker, H. B. editors, Gaia in Turmoil: Climate Change, Biodepletion, and Earth Ethics in an Age of Crisis. The MIT Press, 10 2009.

Harvey, I. The circular logic of Gaia: Fragility and fallacies, regulation and proofs. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Artificial Life 2015, Artificial Life Conference Proceedings, pages 90–97, 07 2015.

Equihua, M. et al. Ecosystem antifragility: beyond integrity and resilience. PeerJ 8, e8533 (2020).

Prehofer, C. & Bettstetter, C. Self-organization in communication networks: principles and design paradigms. Commun. Mag., IEEE 43, 78–85 (2005).

Holland, O. & Melhuish, C. Stigmergy, self-organization, and sorting in collective robotics. Artif. Life 5, 173–202 (1999).

Dorigo, M. et al. Evolving self-organizing behaviors for a swarm-bot. Auton. Robots 17, 223–245 (2004).

Zykov, V., Mytilinaios, E., Adams, B. & Lipson, H. Self-reproducing machines. Nature 435, 163–164 (2005).

Pfeifer, R., Lungarella, M. & Iida, F. Self-organization, embodiment, and biologically inspired robotics. Science 318, 1088–1093 (2007).

Werfel, J., Petersen, K. & Nagpal, R. Designing collective behavior in a termite-inspired robot construction team. Science 343, 754–758 (2014).

Rubenstein, M., Cornejo, A. & Nagpal, R. Programmable self-assembly in a thousand-robot swarm. Science 345, 795–799 (2014).

Reina, A., Valentini, G., Fernández-Oto, C., Dorigo, M. & Trianni, V. A design pattern for decentralised decision making. PLOS ONE 10, 1–18 (2015).

Vásárhelyi, Gábor et al. Optimized flocking of autonomous drones in confined environments. Sci. Robot., 3(20), 2018.

Schranz, M., Umlauft, M., Sende, M., and Elmenreich, W. Swarm robotic behaviors and current applications. Front. Robot. AI, 7, 2020.

Van Calck, Ludéric, Pacheco, A., Strobel, V., Dorigo, M. & Reina, A. A blockchain-based information market to incentivise cooperation in swarms of self-interested robots. Sci. Rep. 13, 20417 (2023).

Ko, H., Lauder, G. & Nagpal, R. The role of hydrodynamics in collective motions of fish schools and bioinspired underwater robots. J. R. Soc. Interface 20, 20230357 (2023).

Cully, A., Clune, J., Tarapore, D. & Mouret, Jean-Baptiste Robots that can adapt like animals. Nature 521, 503–507 (2015).

Ashby, W. R. Design for a brain: The origin of adaptive behaviour. Chapman & Hall, London, 2nd edition, 1960.

Heylighen, F. The science of self-organization and adaptivity. In Kiel, L. D. editor, The Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. EOLSS Publishers, Oxford, 2003.

Lemov, R. Running amok in labyrinthine systems: The cyber-behaviorist origins of soft torture. limn, 1, 2011.

Walter, W. G. An imitation of life. Sci. Am. 182, 42–45 (1950).

Walter, W. G. A machine that learns. Sci. Am. 185, 60–63 (1951).

McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biol. 5, 115–133 (1943).

Lettvin, J. Y., Maturana, H. R., McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. H. What the frog’s eye tells the frog’s brain. Proc. IRE 47, 1940–1951 (1959).

Rocha, L. M. Selected self-organization and the semiotics of evolutionary systems. In van de Vijver, G., Salthe, StanleyN., and Delpos, M. editors, Evolutionary Systems, pages 341–358. Springer Netherlands, 1998.

Chialvo, D. R. Emergent complex neural dynamics. Nat. Phys. 6, 744–750 (2010).

Haimovici, A., Tagliazucchi, E., Balenzuela, P. & Chialvo, D. R. Brain organization into resting state networks emerges at criticality on a model of the human connectome. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 178101 (2013).

Gershenson, C. Computing networks: A general framework to contrast neural and swarm cognitions. Paladyn. J. Behav. Robot. 1, 147–153 (2010).

Wei, J. et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv:2206.07682, 2022.

Agüera y Arcas, B. Do large language models understand us? Daedalus 151, 183–197 (2022).

Mitchell, M. AI’s challenge of understanding the world. Science 382, eadm8175 (2023).

Zipf, G. K.Selective Studies and the Principle of Relative Frequency in Language. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1932.

Ferrer i Cancho, R. & Solé, R. V. Least effort and the origins of scaling in human language. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 100, 788–791 (2003).

Baek, SeungKi, Bernhardsson, S. & Minnhagen, P. Zipf’s law unzipped. N. J. Phys. 13, 043004 (2011).

Corominas-Murtra, B., Fortuny, J., and Solé, R. V. Emergence of Zipf’s law in the evolution of communication. Phys. Rev. E, 83:036115, 2011.

Iñiguez, G., Pineda, C., Gershenson, C. & Barabási, A.-L. Dynamics of ranking. Nat. Commun. 13, 1646 (2022).

Steels, L. A self-organizing spatial vocabulary. Artif. Life 2, 319–332 (1995).

Steels, L. The synthetic modeling of language origins. Evol. Commun. 1, 1–34 (1997).

Beuls, K. and Steels, L. Agent-Based Models of Strategies for the Emergence and Evolution of Grammatical Agreement. PLoS ONE, 8(3):e58960+, March 2013.

Axelrod, R. Advancing the art of simulation in the social sciences. In Rennard, Jean-Philippe editor, Handbook of Research on Nature Inspired Computing for Economy and Management. Idea Group, Hershey, UK, 2005.

Epstein, J. M. and Axtell, R. L.Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up. Brookings Institution Press MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996.

Lazer, D. et al. Life in the network: the coming age of computational social science. Science 323, 721 (2009).

Conte, R. et al. Manifesto of computational social science. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 214, 325–346 (2012).

Batty, M. Modelling cities as dynamic systems. Nature 231, 425–428 (1971).

Portugali, J. Self-organization and the City. Springer Verlag, 2000.

Batty, M. Cities and complexity. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005.

Bettencourt, L. & West, G. A unified theory of urban living. Nature 467, 912–913 (2010).

Bettencourt, L. M. A. The origins of scaling in cities. Science 340, 1438–1441 (2013).

Batty, M. The New Science of Cities. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, November 2013.

Gershenson, C. Living in living cities. Artif. Life 19, 401–420 (2013).

Murcio, R., Masucci, A. P., Arcaute, E. & Batty, M. Multifractal to monofractal evolution of the london street network. Phys. Rev. E 92, 062130 (2015).

Lämmer, S. & Helbing, D. Self-control of traffic lights and vehicle flows in urban road networks. J. Stat. Mech. 2008, P04019 (2008).

Zubillaga, Darío et al. Measuring the complexity of self-organizing traffic lights. Entropy 16, 2384–2407 (2014).

Zapotecatl, J. L., Rosenblueth, D. A. & Gershenson, C. Deliberative self-organizing traffic lights with elementary cellular automata. Complexity 2017, 7691370 (2017).

Gershenson, C., Santi, P., and Ratti, C. Cybernetic cities: designing and controlling adaptive and robust urban systems. In Portugali, J. editor, Handbook on Cities and Complexity, chapter 10, pages 195–208. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021.

Grassi, M. Self-organized bodies, between politics and biology. a political reading of aristotle’s concepts of soul and pneuma. Sci. et. Fides 8, 123–139 (2020).

Van de Vijver, G. Kant and the intuitions of self-organization. In Feltz, B., Crommelinck, M., and Goujon, P. editors, Self-organization and emergence in life sciences, pages 143–161. Springer, 2006.

Campbell, D. T. ‘Downward causation’ in hierarchically organized biological systems. In Ayala, F. J. and Dobzhansky, T. editors, Studies in the Philosophy of Biology, pages 179–186. Macmillan, New York City, NY, USA, 1974.

Bitbol, M. Downward causation without foundations. Synthese 185, 233–255 (2012).

Flack, J. C. Coarse-graining as a downward causation mechanism. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 375, 20160338 (2017).

Farnsworth, K. D., Ellis, George F. R., and Jaeger, L. Living through downward causation: From molecules to ecosystems. In Walker, Sara Imari, Davies, Paul C. W., and Editors Ellis, George F. R. editors, From Matter to Life: Information and Causality, pages 303–333. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2017.

De Wolf, T., Samaey, G., and Holvoet, T. Engineering self-organising emergent systems with simulation-based scientific analysis. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Engineering Self-Organising Applications, pages 46–160, Utrecht, The Netherlands„ 2005.

Rohden, M., Sorge, A., Timme, M. & Witthaut, D. Self-organized synchronization in decentralized power grids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 064101 (2012).

Dressler, F. Self-Organization in Sensor and Actor Networks. John Wiley & Sons, December 2007.

Helbing, D., Seidel, T., Lämmer, S., and Peters, K. Self-organization principles in supply networks and production systems. In Chakrabarti, B. K., Chakraborti, A., and Chatterjee, A. editors, Econophysics and Sociophysics, pages 535–559. Wiley, Weinheim, 2006.

Gershenson, C. Towards self-organizing bureaucracies. Int. J. Public Inf. Syst. 2008, 1–24 (2008).

Prokopenko, M. Guided self-organization. HFSP J. 3, 287–289 (2009).

Prokopenko, M. editor. Guided Self-Organization: Inception, volume 9 of Emergence, Complexity and Computation. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2014.

Taleb, Nassim Nicholas Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder. Random House, London, UK, 2012.

Pineda, O. K., Kim, H. & Gershenson, C. A novel antifragility measure based on satisfaction and its application to random and biological Boolean networks. Complexity 2019, 10 (2019).

Kim, H., Pineda, O. K. & Gershenson, C. A multilayer structure facilitates the production of antifragile systems in Boolean network models. Complexity 2019, 11 (2019).

López-Díaz, Amahury Jafet, Sánchez-Puig, F., and Gershenson, C. Temporal, structural, and functional heterogeneities extend criticality and antifragility in random Boolean networks. Entropy, 25(2), 2023.

Gershenson, C. & Helbing, D. When slower is faster. Complexity 21, 9–15 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The author owes everything to his coaches.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gershenson, C. Self-organizing systems: what, how, and why?. npj Complex 2, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44260-025-00031-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44260-025-00031-5