Main

Theorem proving—the ability to navigate from axioms to conclusions through logically connected intermediate statements—represents one of the most sophisticated forms of human reasoning. For millennia, this process remained the exclusive domain of gifted mathematicians. The International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) stands as the premier global competition for identifying exceptional mathematical talent, where medallists demonstrate extraordinary abilities that blend creativity, rigour and spatial intuition. Geometry problems within these competitions have emerged as a critical benchmark for artificial intelligence (AI) researchers, presenting formidable challenges due to their unique combination of formal logic and spatial reasoning1,2,3,4,5.

Problem proposing represents an equally esteemed—arguably more challenging—intellectual endeavour in mathematics competitions. Formulating original, elegant problems requires not only mathematical mastery but also aesthetic sensibility, rarely captured computationally. Although considerable progress has been made in automated theorem proving, autonomous problem generation with rigorous verification remains largely unexplored. Exemplary olympiad problems emerge from extensive mathematical foundations, typically building on intermediate theorems developed over decades. The most admired problems exhibit deceptive simplicity: accessible through fundamental knowledge yet demanding profound creativity for complete solutions. Mathematical elegance, particularly symmetry in various forms, serves as a critical quality criterion in prestigious competitions.

Computational approaches to olympiad mathematics encounter fundamental limitations from the combinatorial explosion of reasoning paths and scarcity of exemplar problems for heuristic development. Geometry presents particularly formidable obstacles due to its unique blend of numerical precision and spatial reasoning—a combination that resists text-based methodologies successful in other mathematical domains. Although large language models (LLMs) have substantially advanced other mathematical areas6,7, geometry’s inherently visual and constructive nature defies such adaptation. Recent research has introduced specialized frameworks for formalizing geometric problems in proof assistants8,9,10 and domain-specific languages for geometric reasoning11,12,13,14,15, yet these approaches remain constrained by their representational frameworks, leaving substantial portions of olympiad-level geometry unexplored.

Here we introduce TongGeometry (Tong stands for ‘general’ in Chinese), a tree-based system for synthetic Euclidean planar geometry, enabling both human-readable problem proposing through backward tracing and theorem proving via forward chaining. Using this scalable system with 196 olympiad problems as guiding statistics, we generated a repository of 6.7 billion geometry problems requiring auxiliary constructions, including 4.1 billion exhibiting mathematical symmetry—a quality highly prized in competitions. Unlike existing systems that function as ‘students’ merely solving assigned problems12,13,14,15, TongGeometry operates as a ‘coach’ that systematically characterizes geometric relationships through a finite tree structure, enabling both guided symmetric problem proposing and solving (Fig. 1). Our comprehensive evaluation metrics assessed problem difficulty and competition suitability, leading to real-world impact: one problem selected for the 2024 National High School Mathematics League (Beijing)—a Chinese National Team qualifying competition—and two problems for the 2024 US Ersatz Math Olympiad shortlist.

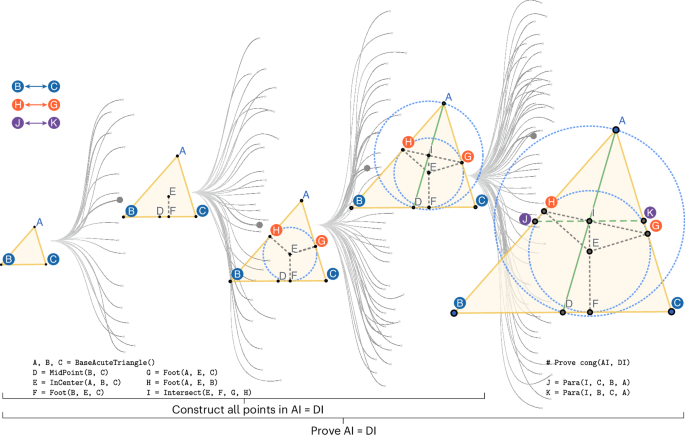

This diagram illustrates TongGeometry’s approach to navigate a tree-shaped geometry space and maintain symmetry. A colour-coded symmetry map (left; B↔C, H↔G and J↔K) ensures that symmetric action pairs are always executed together, with the map being dynamically updated throughout construction. The central insight of TongGeometry is identifying problems requiring auxiliary constructions by detecting when a fact’s construction dependency (points needed to state the fact) forms a proper subset of its proof dependency (points needed to prove the fact). In this example, proving AI = DI requires constructing points J and K as auxiliaries. The problem can then be formulated by presenting the construction sequence as context and requiring the solver to discover the necessary auxiliary constructions.

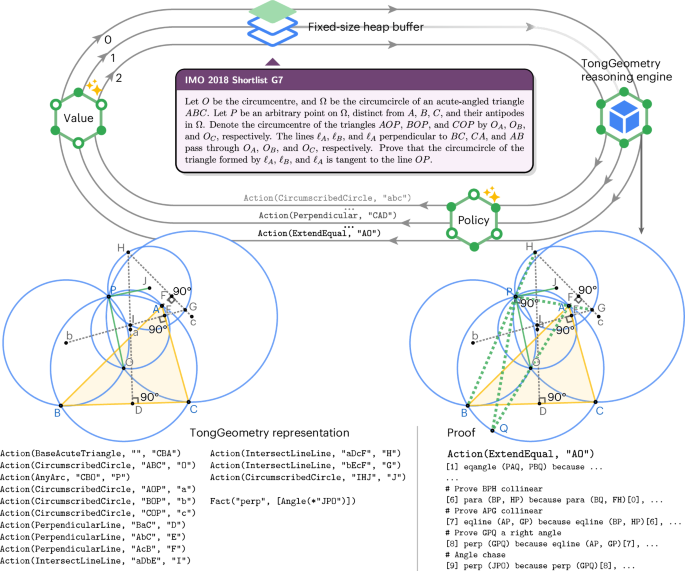

From a dual perspective of proposing and solving, our generated repository contains rich auxiliary constructions essential for geometric theorem proving. These exogenous objects—additional points, lines and circles absent from original problem statements—serve as critical bridges connecting the initial conditions to the desired conclusions. We leveraged this extensive collection to guide TongGeometry’s tree search for unseen problem solving (Fig. 2). We fine-tuned two complementary LLMs16,17: one suggesting promising search directions, another estimating required reasoning steps along each path. When evaluated on the IMO-AG-30 benchmark comprising geometry problems from 23 years of IMO competitions, our neuro-symbolic system solved every problem within 38 min using consumer-grade computing resources (32 CPU cores and a single GPU). This achievement represents the first automated system to surpass the average IMO gold medallist performance on this benchmark14. Note that we do not claim TongGeometry surpasses an average IMO gold medallist in geometry generally.

This figure illustrates TongGeometry’s approach to solving IMO-level geometry problems through neural-guided reasoning. Given a problem (top centre; IMO 2018 Shortlist G7), TongGeometry processes its domain-specific representation through a dual-model system: a policy model (bottom right) that generates candidate auxiliary constructions, and a value model (left) that estimates the remaining steps needed to reach a solution. The system maintains a fixed-size heap buffer that prioritizes promising construction paths based on their estimated utility scores. The reasoning engine executes selected constructions, producing both geometric representation (bottom left) and formal proof (bottom right). This architecture enables an efficient exploration of the solution space by focusing computational resources on the most promising auxiliary constructions.

Although similar to recent works, our primary scientific contribution lies not in incremental performance gains, but in a fundamental recharacterization and understanding of the geometry problem space itself that enables efficient problem finding and solving under computational budgets readily accessible to academic laboratories and enthusiasts. We achieve this partly by designing a unified symbolic engine that introduces a definite and Markovian search space, allowing for the efficient caching of fruitful intermediate states. But more crucially, we introduce methods for handling mathematical symmetry through a canonical representation, which collapses redundant search paths (that prior systems would explore wastefully) and accelerates discovering problems of mathematical elegance that humans value. By using real competition problems as statistical priors to inform a data-driven search, we further guide the system towards more plausible problem configurations that are competition-worthy, that is, hard enough to require mathematical ingenuity to solve but also elegant in the sense that the problem is concise and symmetric. Collectively, these innovations create a vastly more efficient search landscape, allowing TongGeometry to discover and solve previously intractable problems with a fraction of the computational budget, thereby laying a more structured and efficient foundation for automated mathematical discovery.

Geometry as a Markov process on a finite tree

TongGeometry approaches geometry through a Markovian framework, specifically modelling it as a Markov chain18,19. In this formulation, states represent geometric diagrams constructed through action sequences, encompassing both the diagram itself and all derivable facts at that step. The action space expands dynamically as new geometric objects—points, lines and circles—are introduced. Supplementary Table 1 provides a comprehensive list of action types. Each action triggers a deterministic state transition, generating not only new geometric constructs but also additional derivable facts. TongGeometry, therefore, represents states as action sequences, with complex geometric diagrams evolving incrementally from an empty canvas through the systematic addition of geometric elements.

During each state transition, TongGeometry uses the deductive database method to derive new facts20. Beginning with seed facts introduced by each action, the system recursively applies applicable deduction rules to generate additional facts, with Supplementary Table 2 listing the complete rule set. The derived facts are cached for efficient retrieval, and the deductive process continues until achieving logical closure. Unlike recent comparable systems14,15, TongGeometry integrates algebraic reasoning directly within the deductive database rather than as a separate component (Methods). This architectural integration simplifies reasoning and enhances computational efficiency.

This stepwise Markovian perspective naturally formulates geometric reasoning as search in a tree structure. TongGeometry renders this tree finite through strategic pruning and equivalence identification: deductive database rules eliminate impossible actions, whereas ordered canonical representation (Methods) removes equivalent ones. Through this approach, geometry becomes precisely characterized as a Markov process on a finite tree. Within TongGeometry’s framework, the state space of mirror-symmetric canonical diagrams comprising up to 28 actions reaches an estimated 1056 distinct configurations.

Discovering problems during tree search

In TongGeometry, every new fact emerges through established rule application: when specific conditions (parent facts) are satisfied, a child fact can be deduced according to the corresponding rule. These logical dependencies naturally form a relational dependency graph of facts. For any given fact, its dependency subgraph corresponds to a proof action sequence within the diagram—representing the minimum action sequence required to construct every element necessary for the proof. Each fact also possesses a construction sequence within the diagram, constituting the minimum action sequence needed to draw all elements explicitly mentioned in the fact. This fundamental distinction yields a key insight: when a fact’s construction sequence forms a proper subset of its proof sequence, a meaningful geometry problem emerges. The construction sequence establishes the problem context, the fact itself becomes the theorem to prove, and critically, the difference between proof and construction sequences identifies the auxiliary constructions—precisely the elements that problem solvers must discover. Figure 1 illustrates this problem formulation process.

This observation transforms problem proposing into structured tree search through an expansive problem space. Beginning from a root node representing an empty canvas, each valid geometric action advances the search to a new node one layer deeper. Once deductive closure is achieved at any node, TongGeometry systematically evaluates each newly derived fact, examining whether its construction sequence constitutes a proper subset of its proof sequence (Methods). When this criterion is satisfied, TongGeometry identifies a geometry problem requiring auxiliary constructions, with these auxiliary elements precisely defined as the difference between the two sequences.

A dual perspective of proposing and proving

The fundamental observation that geometry problems emerge when a fact’s construction sequence forms a proper subset of its proof sequence reveals an elegant duality between problem proposition and problem solving. From this perspective, problem proposing involves examining a given diagram and systematically identifying facts whose construction sequences are proper subsets of their corresponding proof sequences. Conversely, problem solving requires bridging the critical gap between a fact’s construction sequence and its proof sequence. This duality highlights the central role of auxiliary constructions in geometric reasoning: when a solver successfully identifies and implements the appropriate auxiliary constructions—precisely those elements present in the proof sequence but absent from the construction sequence—the problem can be efficiently solved.

Results

Proposing and evaluating problems for olympiad

Symmetry represents a hallmark of mathematical beauty and constitutes a highly valued characteristic in olympiad problems. TongGeometry natively supports symmetric problem generation through its stepwise Markovian formulation. The system maintains a base symmetry map, tracking known symmetric elements throughout the construction process. When executing new actions, TongGeometry consults this symmetry map to identify corresponding symmetric actions, immediately performs them and updates the map accordingly (Fig. 1 and Methods). This mechanism ensures the generation of symmetric diagram configurations. Beyond geometric symmetry, truly symmetric problems require symmetric facts, too. Using the established symmetry map, TongGeometry verifies whether the derived facts maintain symmetry—for instance, if points A and C are symmetric, then the fact ‘AB and BC are on the same line’ constitutes a symmetric fact. The system accommodates multiple symmetry types: self-symmetry, mirror symmetry and rotational symmetry.

Although symmetry provides essential constraints, it alone cannot efficiently navigate geometry’s vast problem space to identify olympiad-calibre problems. We, therefore, implemented a data-driven approach, collecting 196 olympiad problems from prestigious competitions including 44 from IMO, 44 from IMO Shortlist, 17 from United States of America Mathematical Olympiad, 6 from United States of America Junior Mathematical Olympiad, 1 from China Mathematics Olympiad, 8 from United States of America Team Selection Test, 10 from United States of America Team Selection Test Selection Test, 44 from China Team Selection Test, 1 from US Ersatz Math Olympiad, 1 from National High School Mathematics League and the rest from famous theorems. These problems were formalized in TongGeometry’s domain-specific language and utilized as guiding statistics during tree search operations.

To enhance search efficiency, we used a replay buffer, caching promising intermediate configurations and enabling strategic search resumption from cached states rather than repeatedly starting from empty canvases. Additionally, we developed comprehensive automatic rubrics to evaluate both difficulty and olympiad suitability of discovered problems.

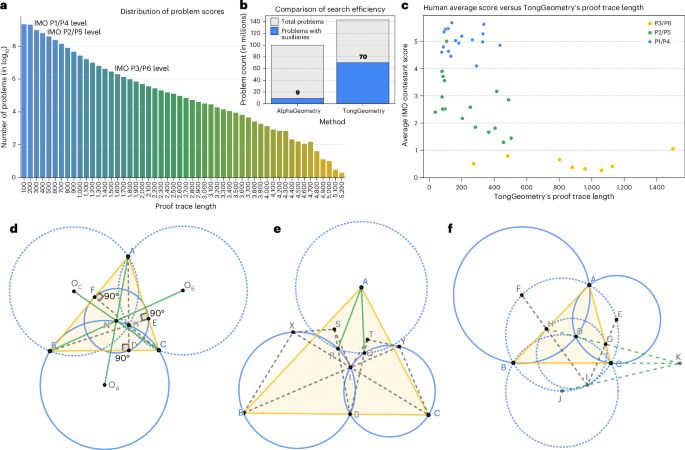

Guided by statistics from existing 196 olympiad problems, we conducted massive parallel problem search utilizing 10,368 CPU cores over 30 days. TongGeometry traversed 143,379,886 unique paths (total, 170,883,417) within the defined geometry space, inferring over 1,851,166,755 unique states. Each unique path yielded an average of 0.7613 configurations requiring auxiliaries, generating 109,157,477 configurations (context–auxiliary pairs). Among these, 70,703,508 were unique. After systematic filtering, we compiled a dataset of 6,688,310,403 problems (context–goal–auxiliary triplets), with 4,096,680,574 exhibiting symmetry. Figure 3b compares our search efficiency with AlphaGeometry, and Supplementary Table 3 lists the auxiliary length distributions.

a, Distribution of proof trace length across the generated geometry problems. b, Comparative analysis of search efficiency between TongGeometry and AlphaGeometry, showing TongGeometry’s effectiveness in both problems found with auxiliaries and without auxiliaries. c, Correlation analysis between human-assigned difficulty scores and TongGeometry’s proof trace length for problems at different IMO difficulty levels, demonstrating that longer proof traces generally correspond to problems human experts find more challenging. d, A known lemma was independently discovered by TongGeometry during its search process, showing an elegant construction involving the nine-point circle. e, A symmetric problem proposed by TongGeometry that was shortlisted in the 2024 US Ersatz Math Olympiad (USEMO), challenging solvers to prove that AP and AQ are congruent. f, The Mixtilinear Incircle configuration was automatically identified in TongGeometry’s search buffer, illustrating the system’s capacity to rediscover important geometric configurations.

Selecting olympiad-suitable problems from billions of candidates presented notable challenges due to absent automated assessment criteria. Drawing inspiration from GeoGen’s methodology13, we developed comprehensive selection rubrics based on several key metrics. Proof trace length measures the total edge count in a fact’s dependency graph, accounting for the number of conditions required by each rule—recognizing that rules with more conditions are inherently more challenging to identify. Our evaluation reveals that proof trace lengths for easy-level IMO problems (P1 and P4) typically remain below 300, medium-level problems (P2 and P5) range up to 500 and hard-level problems (P3 and P6) can reach 1,500. Figure 3a illustrates proof trace length distributions across searched problems, whereas Fig. 3c demonstrates relationships between proof trace lengths and difficulty levels.

Additional metrics include the number of context actions, quantifying steps required to construct initial problem diagrams, the number of new facts per auxiliary action indicating how targeted these auxiliaries are and symmetry-type preferences favouring self-symmetry over mirror or rotational symmetry.

Before submission deadlines for the 2024 National High School Mathematics League (Beijing) and 2024 US Ersatz Math Olympiad, we enlisted a 2023 IMO gold medallist and a Chinese National Team student member to evaluate proposal batches during initial search phases. We submitted four proposals to the 2024 National High School Mathematics League (Beijing), with one selected as the competition’s only geometry problem. Additionally, six proposals were submitted to the 2024 US Ersatz Math Olympiad, with two advancing to the shortlist (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). In particular, AlphaGeometry successfully solved only three of our ten proposals.

Search discovers known lemmas and base configurations

TongGeometry’s systematic exploration of the geometric problem space yielded an unexpected validation: the rediscovery of several well-established geometric lemmas and foundational configurations. This emergent behaviour demonstrates that our search methodology naturally converges towards mathematically important structures, lending credibility to the overall approach.

Among the proposed problems, TongGeometry rediscovered numerous classical results. Figure 3d illustrates one such example—a rotationally symmetric lemma in which three green lines meet at the nine-point centre21,22. This rediscovery occurred naturally during the search process without explicit guidance towards known results, suggesting that our search heuristics effectively identify mathematically meaningful configurations.

The replay buffer mechanism proved instrumental not only for computational efficiency but also for discovering foundational geometric configurations. Rather than repeatedly starting from empty canvases, this mechanism enables tree search to resume from cached promising intermediate states. These intermediate states frequently correspond to configurations widely recognized in the geometric community, serving as productive scaffolds for constructing more sophisticated problem scenarios. Figure 3f shows an example of this phenomenon, presenting a symmetric configuration featuring both the mixtilinear incircle23 and the incenter/excenter lemma24. This particular configuration has been characterized as the ‘richest configuration’ by a coach of the US team23, highlighting how our automated search naturally identifies structures that human experts consider particularly valuable. Appendices E and F in the Supplementary Information provide detailed explanations of these geometric phenomena and their mathematical significance.

Proving olympiad geometry

Leveraging the extensive auxiliary construction dataset generated during problem proposition, we harnessed transformer-based17,25 language models to train systems capable of identifying crucial auxiliary constructions. We serialized training data into the structured format ‘〈Context〉 〈Goal〉 〈Auxiliaries〉’ and fine-tuned two code-pretrained language models16 to implement an actor–critic-style18 guided tree search. The policy model suggests promising next actions based on problem context, goals and existing auxiliaries, whereas the value model estimates the remaining number of actions needed to complete proofs.

During inference, the policy model samples multiple candidate actions, whereas the value model estimates the number of remaining steps until solution for each potential path. When a promising action is selected, TongGeometry advances the diagram tree by one step and applies the deductive database method until logical closure is achieved. If the goal fact appears in the deductive database, the proof succeeds. Otherwise, the process repeats until reaching the maximum search depth (Fig. 2). We use beam search (beam scaling is discussed in Appendix C in the Supplementary Information) with parallelization on consumer-grade machines to substantially accelerate the search process.

We conducted quantitative analysis on two benchmarks: the IMO-AG-30 dataset curated for AlphaGeometry and our freshly developed MO-TG-225 dataset. IMO-AG-30 comprises 30 problems translated from 23 years of IMO competition problems into AlphaGeometry’s domain-specific language. MO-TG-225 contains 225 mathematical olympiad problems selected from our pool of 196 examples used for search statistics, translated into TongGeometry’s domain-specific language with none appearing in TongGeometry’s training dataset.

We compared TongGeometry against AlphaGeometry, GPT-4o6 and o1. Since TongGeometry and AlphaGeometry use different domain-specific languages, we translated each problem’s original representation into the appropriate required language. For GPT-4o and o1 evaluation, we used the natural language format in which problems were originally presented in competitions. All models were assessed under a standardized 90-min time limit per problem.

Table 1 (left) presents performance comparisons across different models and human averages on IMO-AG-30. Despite recent reasoning-enhanced language models like o1 achieving impressive results on various tasks, we observed that language models still struggle with rigorous mathematical reasoning in geometry, frequently generating proofs containing erroneous logic and hallucinated intermediate results. AlphaGeometry’s DD+AR approach particularly improved on Wu’s method (ten solves), yet its symbolic reasoning engine remains both redundant and suboptimal. By redesigning and optimizing the deductive database method, TongGeometry’s reasoning backend using only DD successfully solved 18 problems—outperforming average IMO contestants in the dataset. Note that this does not mean TongGeometry surpasses an average IMO contestant in geometry generally. With learned value heuristics, TongGeometry became the first method to surpass IMO gold medallists, successfully proving all 30 benchmark problems. Detailed analysis revealed that the value model proved instrumental in solving the benchmark’s two most challenging problems: IMO 2000 P6 and IMO 2008 P6. Compared with AlphaGeometry, TongGeometry achieved these results on a consumer-grade machine with 32 CPU cores and a single NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU in a maximum of 38 min (Fig. 2), whereas AlphaGeometry required 246 CPU cores and 4 NVIDIA V100 GPUs to reduce the solve time to under 90 min—a resource-intensive configuration inaccessible to most users. Table 1 (right) shows the performance results on the MO-TG-225 dataset. Unlike the IMO dataset, MO-TG-225 includes problems from diverse sources, making rigorous human evaluation benchmarks unavailable. During GPT-4o and o1 evaluation, we observed that when prompted to prove known theorems such as the Euler line theorem, language models frequently assumed the theorem as established and applied it directly without providing the requested proof. We counted these responses as correct, accounting for the few solves reported in the table. Consistent with the IMO-AG-30 results, TongGeometry’s DD backend demonstrated an improved problem-solving capability over AlphaGeometry’s DD+AR, reaching performance levels close to AlphaGeometry overall. We noted that AlphaGeometry’s success largely stemmed from its backend engine, with 72.5% of total solves achieved by DD+AR. By contrast, TongGeometry not only solved a greater proportion of problems (81.3% versus 45.3%) but also more effectively leveraged its neural models to address auxiliary construction challenges, with only 55.2% of the problems solved by DD alone.

Ablation studies on value heuristics suggest that in resource-constrained environments of 32 cores and 1 graphics card, the value model further enhanced performance, yielding 7.1% (IMO-AG-30) and 3.4% (MO-TG-225) improvement over policy-only models.

Expert evaluation on TongGeometry results

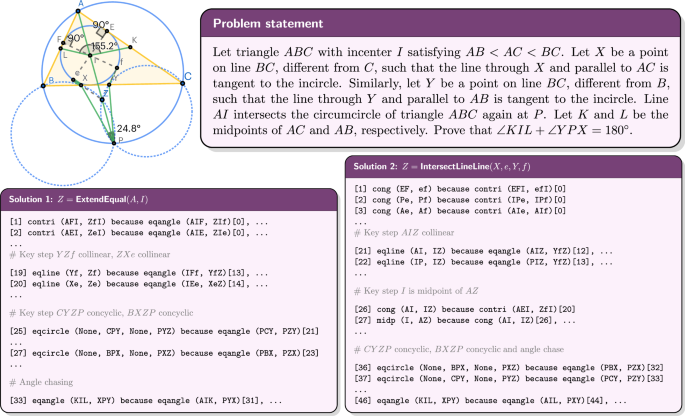

To demonstrate TongGeometry’s problem-solving capabilities on contemporary competition problems, we evaluated its performance on IMO 2024 P4 (Fig. 4) and IMO 2025 P2—the geometry problems from the most recent IMO competition. This problem represents a particularly stringent test case since they only came after TongGeometry’s training.

The figure presents two distinct solution approaches generated by TongGeometry for problem 4, IMO 2024—a challenging geometry problem that appeared after the system’s training period. The problem (purple box, top) involves a triangle ABC with incentre I and specifically constructed points X and Y on the sides BC, requiring proof that ∠KIL + ∠YPX = 180°, where K and L are the midpoints of AC and AB. TongGeometry independently constructed the same auxiliary point Z as the official solution, but through two different methods: extension of a point (Solution 1) and line intersection (Solution 2). Both proofs were verified for correctness by a 2024 IMO gold medallist. Since TongGeometry uses a full-angle representation system, it proves the equivalent statement: ∠KIL = ∠XPY. This demonstrates TongGeometry’s capability to generate mathematically valid proofs for previously unseen olympiad-level problems.

For IMO 2024 P4, TongGeometry successfully generated two equivalent solutions for this problem. Remarkably, both solutions independently identified and introduced an auxiliary point identical to the one presented in the official solution26, demonstrating that the system’s auxiliary construction strategy aligns with expert mathematical reasoning. To ensure the validity of these results, we invited a 2024 IMO gold medallist to independently evaluate TongGeometry’s solutions. The expert confirmed that both generated proofs were mathematically correct and followed sound logical reasoning throughout.

For IMO 2025 P2, TongGeometry proved the problem without even introducing any auxiliary points, showcasing the power of its deductive database. The solution was also independently verified by human experts and confirmed to be correct.

TongGeometry for mathematical education

TongGeometry has been deployed in a pioneering application for real-world mathematical education (Supplementary Fig. 14 shows a screenshot). In a weekly competition, TongGeometry’s proposed problems are meticulously reviewed, edited and refined by experienced IMO coaches who adjust difficulty, enhance pedagogical value and ensure they align with the curriculum. This curated collection is then presented to students, serving a dual purpose: it provides a rich source of training material that helps students master complex topics and competition-specific techniques, simultaneously acting as a powerful creative aid for coaches and helping them to brainstorm interesting and challenging problems for their teams.

Discussion

We present TongGeometry, a neuro-symbolic system that discovers, proposes and proves IMO-level geometry problems through principled tree search. The system’s architecture leverages Markovian principles to organize the geometric search space as a finite tree, uses data-driven statistics from existing olympiad problems to guide problem proposition and utilizes neural models to direct auxiliary construction identification during problem solving.

TongGeometry’s dual capability in both problem proposition and problem solving represents a notable advancement in computational geometry. For problem proposition, we developed comprehensive evaluation rubrics that assessed mathematical difficulty and olympiad suitability, achieving notable real-world validation when one proposed problem was selected for the 2024 National High School Mathematics League (Beijing)—a Team China qualifying competition—and two additional problems were shortlisted in the 2024 US Ersatz Math Olympiad, a premier civilian mathematics competition in the USA.

For problem solving, TongGeometry implements actor–critic-style inference in which a policy model learns to identify crucial auxiliary constructions, whereas a value model estimates the number of remaining proof steps. This approach achieved unprecedented super-average-gold-medallist performance on established IMO geometry benchmarks, becoming one of the first automated systems to surpass this threshold and demonstrate superior resource efficiency compared with previous state-of-the-art methods.

A fundamental design choice in TongGeometry is the use of a statistical prior from existing human-generated competition problems. This methodology is highly effective at exploiting the known landscape of challenging, human-vetted geometry problems. This design choice, however, represents a key trade-off and a distinction from completely random exploration. By anchoring our generation to this prior, we risk constraining our search to a ‘local optimum’ defined by known human definitions of ‘elegance’, such as symmetry. We may be missing classes of valuable configurations that humans have not yet discovered. By contrast, an approach that explores the problem space more broadly embarks on a high-variance exploration. Its strength lies in its potential to discover truly novel problem structures, unbound by historical human bias. This distinction highlights a classic exploration–exploitation trade-off. The challenge for purely exploratory approaches is a low ‘signal-to-noise’ ratio in the vast space of possible problems. Our method is efficient but bounded; the other is broad but potentially less efficient. This trade-off is a critical area for future exploration.

Although TongGeometry has its own limitations (Appendix G in the Supplementary Information), the distinction between TongGeometry’s dual role as both problem proposer and problem solver suggests an analogy: the system functions more like a coach who both designs training problems and guides solution strategies, rather than merely a student who solves given problems. This perspective opens promising research directions for advancing computational geometry and mathematics education, where systems that can both generate meaningful mathematical challenges and provide solution guidance may prove invaluable for pedagogical applications and mathematical discovery.

Methods

Representing geometry problems

Although Hilbert27 and Tarski28 introduced modifications to address ‘incompleteness’ in axiomatic geometry, Lean’s axiomatic geometry system remains under active development and lacks a diagrammatic sketchpad, with only recent advances making geometry proving in Lean more readable10. Popular tools like GeoGebra12 and GeoGen13 facilitate the drawing of geometric figures, yet independently they do not offer integrated reasoning capabilities. GEX11 combines both drawing and reasoning, but its descriptive language is limited when expressing complex problems in IMO. The recent development of AlphaGeometry14,15 extends the language used in GEX, enhancing its descriptive and reasoning capabilities. However, its design does not adhere to Markovian principles, leaving the geometry space unquantified and unstructured. Newclid29 builds on AlphaGeometry and drawing tools like GeoGebra to offer more user-friendly geometry problem solving. A recent study30 combines Wu’s method with AlphaGeometry to achieve two more solves. TongGeometry integrates the strengths of these previous approaches in a unified framework, offering both a drawing sketchpad and a step-by-step reasoning engine. Excluding geometry algebra and combinatorics from past IMO competitions from 2000 to 2024 (5 out of 43), TongGeometry’s language can represent 86.8% (33 of 38) of Euclidean geometry problems.

Logical system without algebraics

Unlike AlphaGeometry, which uses an additional and dedicated algebraic component in forward chaining, TongGeometry completely discards such a design in favour of a purely logical forward chaining system. Specifically, TongGeometry performs ‘algebraic’ reasoning by transforming it into pure logical rules. For example, in angle chasing, when we know ∠ABC = ∠CDE, TongGeometry’s deductive database builds indices into each angle’s sides, such that AB can find BC and CD can find DE, and vice versa. When a new fact, such as ∠CBD = ∠EDF, is discovered, we examine the indices and find that BC has an opposite side of AB and DE has an opposite side of CD. By replacing the sides with their corresponding opposite sides, we can derive ∠ABD = ∠CDF. This function performs angle chasing without requiring ‘Gaussian elimination’. Similarly, length chasing can be performed using related rules.

Canonical representation

In particular, canonical representation is only used during problem tree search, not to be confused with using TongGeometry’s language to perform forward chaining or problem solving using the policy, as the proposed actions might not follow the canonical representation rules.

The introduction of canonical representation aims to deduplicate and properly formulate the geometry space during search. Consider two alternative construction sequences: A, B, C = BaseAcuteTriangle(); D = InCenter(A, B, C); E = CircumscribedCircle(A, B, C) versus A, B, C = BaseAcuteTriangle(); D = CircumscribedCircle(A, B, C); E = InCenter(A, B, C). As shown in Supplementary Table 1, diagrams corresponding to these two action sequences are identical—an acute triangle with its circumscribed and inscribed circle—differing only in naming. From a search perspective, this duplication unnecessarily consumes search budget, as exploration from these two paths could effectively be merged.

To address this issue, we introduce three rules forming canonical representation:

-

(1)

Actions with shallower point dependency must be executed before deeper ones;

-

(2)

Different types of action with the same point dependency depth must be executed in a fixed order;

-

(3)

Actions of the same type and same dependency depth must be executed in a fixed order.

The ‘point dependency depth’ is defined by the ‘largest’ point an action’s arguments involve. For example, in both sequences above, ABC has depth 0, D has depth 1 and E has depth 2. Following Rule (1), any actions involving D must be executed after those involving just ABC. Therefore, if you want to draw the incentre of triangle ABC and the circumscribed circle of BCD after A, B, C = BaseAcuteTriangle(); D = CircumscribedCircle(A, B, C), in the canonical representation, you must draw the incentre of ABC first.

For Rule (2), we establish a fixed action ordering for operations of the same depth during implementation. For example, InCenter is defined to be executed earlier than CircumscribedCircle. Therefore, in our example sequences, the first one follows canonical representation.

Rule (3) governs the ordering of arguments. Different types of action exhibit different equivalence properties. For instance, InCenter(A, B, C) and InCenter(B, A, C) are identical, and IntersectLineLine(A, B, C, D) and IntersectLineLine(D, C, B, A) are equivalent. Using Rule (3), we select only the smallest ordering as the representative, and for non-equivalent actions, the smaller must be executed before the latter. Therefore, IntersectLineLine(A, B, C, D) and IntersectLineLine(A, C, B, D) are non-equivalent representative actions, where the first must be taken before the second.

In implementation, actions are ordered based on these three rules, and after taking one action in the action list, all actions before the selected position become invalid. Through this formulation, canonical representation effectively deduplicates search paths that are syntactically different but semantically identical.

Additional pruning

Beyond canonical representation, TongGeometry uses integrated real-time drawing and step-by-step reasoning to further prune invalid and equivalent actions during problem tree search. For example, if points A, B and C are collinear, the action to draw the circumcircle of ABC is automatically identified as invalid (since three collinear points cannot define a unique circle). Similarly, when A, B and C are collinear, drawing a perpendicular line from an external point D to either line AB or line AC is recognized as equivalent (as these would produce identical perpendicular lines).

This pruning strategy, in conjunction with canonical representation, reduces the problem search tree by eliminating geometrically impossible or redundant constructions. The resulting representation space maximizes the semantic uniqueness of geometric problems and enables a precise quantification of the geometry space—a critical advancement for systematic problem generation and evaluation.

Achieving symmetry

During search on the tree, randomly selecting a child node to advance one step deeper rarely generates symmetric diagrams. To address this, we introduce a symmetry map data structure that assists in symmetric diagram generation. Implementation wise, the symmetry map is a Python dictionary that maps each point to its symmetric counterpart. When taking an action, we immediately execute its symmetric version by mapping the points in its arguments using the symmetry map. Figure 1 demonstrates the generation of mirror-symmetric diagrams. The symmetry dictionary is initialized to map B↔C and A↔A. Note the self-symmetry and corresponding coloured points in the figure. After taking D = MidPoint(B, C), we would typically take its symmetric version D = MidPoint(C, B). However, since B↔C and these two actions are equivalent, we determine that D is self-symmetric; therefore, D↔D. Following similar reasoning, we find that E↔E and F↔F .

For Foot(A, E, C), the mapped action is Foot(A, E, B). As these two actions are non-equivalent, we add G↔H to the symmetry map. Following this method throughout the sequence, I↔I and J↔K. This approach guarantees diagram symmetry. We can also check the fact symmetry. For instance, the fact cong(AI, DI) after symmetric mapping remains cong(AI, DI) (as all points involved are self-symmetric), making it a self-symmetric fact.

For rotational symmetry, the initial mapping for triangle ABC would be A→B, B→C and C→A.

Addressing betweenness

TongGeometry does not take a purely formalist approach to problem proving. Instead, the system embraces the constructive aspect of Euclidean geometry, which is considered a critical component of geometric study. In TongGeometry, both logical deduction and graphical positioning of points play essential roles in proving. To implement this approach, each construction in TongGeometry is accompanied by a corresponding diagram. For proving, the logical system derives results from rules when there is no ambiguity, and otherwise checks the positioning of points to resolve issues like betweenness. Consequently, TongGeometry always proves based on accurate figures, avoiding infamous false proofs such as the ‘all triangles are isosceles’ fallacy.

Regarding math competitions and whether proving under this assumption might lead to point deduction in exams:

-

The hypotheses of competition problems are formulated to, as much as possible, permit only one configuration, as positioning issues are typically considered out of scope for contestants.

-

Marking schemes for problems explicitly instruct graders to ignore configuration issues.

-

However, if a student draws an incorrect figure and proves based on that wrong configuration, they will not earn points.

Estimating geometry space size

Leveraging TongGeometry’s canonical representation and tree space structure, we quantified the size of representable geometry problems of interest. Due to the immense volume of this space, an exhaustive expansion of the search tree is computationally infeasible. Instead, we used statistical sampling techniques for approximation.

Specifically, for mirror-symmetric geometry problems with up to 28 steps of actions, we randomly sampled 1,024 trajectories through the space. For each trajectory, we computed the product of the action space sizes at all steps (under independence assumption), then summed these values across all sampled trajectories and calculated their average to derive our estimate. Through this methodology, the problem space size is estimated to be approximately 1056—an enormously large space that underscores both the richness of geometric constructions and the challenge of effective problem generation.

Deductive database

Our deductive database organizes geometric information into equivalence classes around ten core fact concepts, adapted from the original method20. These foundational concepts include eqline for collinear points, eqcircle for concyclic points, cong for congruent segments, midp for midpoints, para for parallel lines, perp for perpendicular lines (right angles), eqangle for equal angles, eqratio for equal ratios, simtri for similar triangles and contri for congruent triangles. For all facts involving angles, we consistently use full angles20 to ensure computational precision.

Each geometric concept in the database is managed by a dedicated handler that facilitates bidirectional mapping between geometric objects and their corresponding equivalence classes. An equivalence class encompasses all objects sharing a specific property. For instance, when cong(AB, CD) is asserted—indicating segments AB and CD have equal length—these segments are placed in the same equivalence class defined by congruence. The inverse mapping for each segment references back to this equivalence class.

When objects previously belonging to different equivalence classes are identified as equivalent, the handler merges these classes and updates all inverse mappings accordingly. This merging process automatically generates new facts through transitivity. For implementation efficiency, we used sophisticated hashing techniques to optimize these mapping structures, ensuring rapid retrieval and the manipulation of geometric knowledge during problem-solving operations.

Handler

TongGeometry implements one specialized handler for each core predicate mentioned above. These handlers manage the actual deductive database by building efficient indices organized around their respective predicates. For instance, the congruent triangle handler (contri) manages all triangle congruence relationships within the system.

When facts such as contri(ABC, DEF) and contri(ABC, XYZ) are established, the contri handler constructs an equivalence class, using ABC as the representative element. This equivalence class contains the set {ABC, DEF, XYZ}, representing all triangles known to be congruent to each other.

A critical responsibility of each handler is equivalence class merging. For example, if another equivalence class {GHI, JKL} exists and a new fact contri(ABC, GHI) is derived, the handler recognizes that these previously separate classes must be merged into a single unified class: {ABC, DEF, GHI, JKL, XYZ}. The choice of which element serves as the representative is an implementation detail that does not affect the logical structure.

Additionally, each handler maintains an inverse index that maps individual elements directly to their equivalence class representative. This optimization enables rapid access to equivalence classes. For instance, if ABC is designated as the representative element for the merged equivalence class, the inverse index maps every triangle in that class to ABC. This design ensures that finding any element’s complete equivalence class requires only two computational operations: one to identify the representative element, and another to retrieve the entire equivalence class indexed by that representative. This two-hop access pattern considerably enhances the efficiency of geometric reasoning operations.

Forward chaining

TongGeometry’s reasoning process operates as an indefinite loop that continues until a closure condition is satisfied. Each geometric action triggers a forward chaining process, beginning with the ‘seed facts’ introduced by that action.

For example, when applying the circumcircle action to triangle ABC, a new point D is created equidistant from each of the triangle’s vertices. This action automatically adds the facts cong(AD, BD), cong(AD, CD) and cong(BD, CD) to the deductive database. For each newly added fact, two categories of additional facts may be generated:

-

Facts derived directly by the deductive database through transitivity relationships

-

Facts produced by the forward chaining process, which systematically checks every applicable rule to determine if its conditions are satisfied

As new facts are created, dependency relations are automatically constructed, establishing clear links between new facts and their parent facts. To optimize the reasoning process, we use breadth-first search to prioritize the order of fact expansion during forward chaining. This ensures that facts derived at the same level are expanded first, processed in the order they were received.

The reasoning process continues iteratively, propagating through the knowledge graph until either all new facts have been fully processed or a predefined iteration limit is reached, preventing potential infinite loops in complex geometric scenarios.

Construction sequence and proof sequence

Every geometric fact in a diagram is associated with two distinct action sequences: the construction sequence, which details the minimum steps required to construct all the elements involved in the fact, and the proof sequence, which outlines the complete steps needed to prove the fact within the diagram. A fact’s construction sequence can be obtained by tracing the dependency of points in the fact’s arguments, whereas the proof sequence is determined by tracing the dependency of points in all the proof steps.

To illustrate this distinction, we refer to Fig. 1 and take a step-by-step approach. The full action sequence for the entire construction path is as follows: A, B, C = BaseAcuteTriangle(); D = MidPoint(B, C); E = InCenter(A, B, C); F = Foot(B, E, C); G = Foot(A, E, C); H = Foot(A, E, B); I = IntersectLineLine(E, F, G, H); J = Para(I, C, B, A); K = Para(I, B, C, A).

After constructing point K, our deductive database discovers a new fact: cong(AI, DI) (segments AI and DI are congruent). To determine this fact’s construction sequence, we identify the shortest action sequence that constructs all points in the fact—in this case, points A, D and I.

Tracing point dependencies: I depends on EFGH, H depends on ABE, G depends on ACE, F depends on BCE, E depends on ABC, D depends on BC and ABC depends on the initial action. Following this dependency chain, we determine that the minimum action sequence to construct points ADI involves points ABCDEFGHI: A, B, C = BaseAcuteTriangle(); D = MidPoint(B, C); E = InCenter(A, B, C); F = Foot(B, E, C); G = Foot(A, E, C); H = Foot(A, E, B); I = IntersectLineLine(E, F, G, H).

In particular, after constructing point I in this sequence, we cannot immediately derive the fact cong(AI, DI). This indicates that although the fact is true geometrically, its formal proof requires additional auxiliary constructions beyond mere point construction. When examining the proof of cong(AI, DI), we find that points J and K appear in the reasoning chain. Following the same dependency tracing process, we determine that the minimum action sequence to prove the fact requires the complete original sequence.

This distinction between construction sequences and proof sequences is fundamental to understand the relationship between geometric construction and formal geometric proof in TongGeometry.

Backward tracing

Backward tracing relies on the dependency graph of geometric facts to determine proof pathways. Since a fact can potentially be derived through multiple reasoning paths, the dependency graph would ideally be represented as a hypergraph capturing all possible derivations. However, implementing and traversing such a hypergraph structure presents formidable computational challenges, particularly when iterating over all possible subgraphs during proof generation.

To balance computational efficiency with mathematical effectiveness, TongGeometry retains only the proof dependency relation established when a fact is first derived. This approach provides a practical approximation of the complete dependency structure and maintain reasonable performance characteristics.

When a fact’s construction sequence (the minimal steps needed to construct the elements in the fact) is a proper subset of its proof sequence (the steps needed to prove the fact), we identify a potential geometry problem requiring auxiliary constructions. The difference between the proof sequence and the construction sequence represents these necessary auxiliaries.

However, this identification method introduces a potential issue: since our dependency subgraph captures only one possible proof path (the first one discovered), a fact might appear to require auxiliaries when alternative proof paths exist that do not require them, making the identified auxiliaries potentially redundant. To address this limitation, TongGeometry performs additional verification checks to ensure that the identified auxiliary constructions are genuinely necessary for proving the target fact, thereby validating the quality of the generated problem.

Parallel problem search

In our problem search strategy, we primarily target symmetric geometry problems, which are often valued for their mathematical ‘beauty’. However, relying solely on symmetry can lead to inefficiency in the search process. Therefore, we adopted a data-driven approach to guide the tree search more effectively. Specifically, we compiled a dataset of 196 past olympiad geometry problems, translated them into TongGeometry’s language and annotated each one. For each problem step, we recorded the depth at which the action was taken, the depth at which the action was generated, the action type and whether the action was self-symmetric. These annotations provided an action distribution prior that informed our search process. At each search depth, we categorized all valid actions by their generating depth, action type and self-symmetry, sampled one category based on the prior distribution from our dataset and randomly selected an action within the chosen category.

An important challenge in symmetric search is the generation of fully symmetric problems, such as those entirely symmetric with respect to a vertical line. These problems often contain numerous congruence relations that are of limited mathematical interest. The volume of such congruence facts can substantially slow down the reasoning process. To optimize the search efficiency, we estimated a problem’s symmetry rate during the search process using several manually designed metrics, such as the number of perfectly symmetric point pairs. We then terminated the search early on trajectories with a high symmetry rate to prevent unnecessary computational overhead.

In our search process, we incorporated the concept of a priority replay buffer, inspired by techniques from the reinforcement learning community31. For each search instance, we established a replay buffer to cache intermediate diagram configurations that could potentially lead to problems requiring auxiliary constructions. We assessed the utility of these intermediate configurations based on the types of fact they contained that necessitated auxiliaries. Specifically, we assigned utility scores to intermediate configurations: eight for eqline facts, four for eqcircle facts, two for simtri facts and one for cong facts. Configurations with higher utility scores are more likely to generate problems that require multiple auxiliaries, building on facts that depend on earlier discoveries.

Instead of initiating each round of search from a blank slate, we periodically sampled from the buffer according to the distribution of scores among the intermediate nodes. One potential issue with the replay buffer is that high-utility configurations are more likely to have high-utility children, filling the buffer with configurations of similar trajectories and decreasing its diversity. We addressed this by implementing a filtering mechanism that computed the intersection over union and blocked buffer insertion for configurations with a large overlap.

We executed this search strategy on 10,368 parallel CPU cores, each assigned a different random seed. After 30 days of computation, we performed deduplication using a trie tree structure to ensure no two problems shared the same construction sequence. This extensive search process yielded 6.7 billion geometry problems in the canonical form, of which 4.1 billion exhibited symmetry properties.

Data filtering

Before training the language model, we conducted an additional round of data filtering after the deduplication process. Specifically, we excluded problems containing only eqratio, simtri and para facts, as these geometric relationships were generally considered less interesting as final geometry problems, though they often serve as valuable intermediate bridges in more complex proofs. Additionally, problems with context actions exceeding 24 steps were removed to maintain reasonable complexity bounds. The final data distribution resulting from this filtering process is illustrated in Fig. 3a and detailed in Supplementary Table 3. The resulting dataset comprises approximately 10 billion tokens, providing substantial training material for our language models.

Training LLMs

Drawing on advances made in language-based generative learning, we chose a code-pretrained LLM as our starting point. Specifically, we used the DeepSeek-Coder-1.3B-Instruct suite16. This choice aligns with empirical findings17, suggesting that a 1-billion-parameter model is well suited for a 10-billion-token dataset.

Inspired by the success of board-game reinforcement learning agents32,33,34, we trained both a policy model and a value model. The policy model suggests possible actions to take, whereas the value model estimates which actions may lead to better outcomes. In TongGeometry, the policy model serves to generate possible auxiliary constructions, whereas the value model computes how many more steps would be needed if a particular action were taken. Using data points in the format 〈Context〉 〈Goal〉 〈Auxiliaries〉, the policy model is trained to complete the auxiliaries given the context and goal, whereas the value model is trained to predict the remaining number of steps given the context, goal and partial auxiliaries.

We trained the policy model in two stages. Given the large number of unique problems, training on every goal was computationally inefficient. Instead, we grouped data based on configurations (context–auxiliary pairs) that could be associated with multiple goals. In the first stage, we replaced the goal fact with a placeholder; once trained on this representation, we introduced actual goals for further fine-tuning. Preliminary evaluations showed that models trained with vanilla sampling struggled with problems requiring long auxiliaries due to data imbalance (Supplementary Table 3). To address this issue, we dedicated a specialized model to long-auxiliary problems. This model was trained using a uniform number of problems with different auxiliary lengths in each step and underwent both the placeholder pretraining and goal-specific fine-tuning phases. We established a cut-off of 14 steps, such that auxiliaries exceeding 14 steps were treated as being in the 14-step class. Problems not solved within five steps were delegated to this specialized model. In particular, unlike AlphaGeometry14,15, we neither trained models on problems that did not require auxiliaries nor to complete the problem context as in vanilla language modelling—our models were exclusively trained to identify the necessary auxiliaries. The placeholder pretraining for both models lasted for 45,000 steps, with a batch size of 2,048, an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, a warm-up step of 10 and cosine scheduling. The actual goal fine-tuning stage lasted for 200 steps, with a batch size of 2,048, an initial learning rate of 2.5 × 10−5, a warm-up step of 10 and cosine scheduling.

The data imbalance for the value model was even more pronounced, as most problems required only a single auxiliary (Supplementary Table 3), resulting in an overabundance of label 0. To address this imbalance, we applied uniform sampling to ensure each data batch contained approximately equal numbers of each label. A cut-off of 4 was applied, with labels above 4 treated as 4. The value model underwent both placeholder pretraining and goal-specific fine-tuning, following the same training configuration as the policy model.

All models were trained on a computing system equipped with eight NVIDIA A800 80G graphics cards without NVLink.

Parallel problem proving

Given the trained policy and value heuristics, we implemented an efficient beam search algorithm for navigating the tree space when presented with a new geometry problem. At each iteration of the search process, the policy model accepts the string representation of the current problem state and generates n possible next actions. The value model then assesses how many more steps would be required for each of these n candidate actions. Using a weighted combination of the value estimates and accumulated average log probabilities of the actions, we ranked all possible selections and distributed the top-b actions to parallel CPU cores for inference. If the target fact is found in any of the constructed diagrams, the problem is considered solved; otherwise, valid diagrams are retained and the iterative process continues until reaching a predefined maximum step limit.

In particular, TongGeometry implements post-ranking inference, in contrast to AlphaGeometry’s preranking approach. This strategy markedly reduces CPU inference load and enables deeper exploration in the search tree within time- and compute-constrained environments.

In our experiments, we set n to 256 (candidate actions generated) and b to 64 (beam width). We ran TongGeometry inference on a single consumer-grade machine equipped with an Intel Core i9-13900KF processor (32 CPU cores) and one NVIDIA RTX 4090 graphics card. This configuration allowed TongGeometry to complete problem-solving tasks in under 38 min—substantially faster than AlphaGeometry, which required 246 parallel CPU cores and 4 NVIDIA V100 graphics cards to bring the problem-solving time within 1.5 h, a hardware setup generally unavailable to regular consumers. Supplementary Fig. 2 details the solve time for each problem in the IMO-AG-30 benchmark under this setup.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The dataset used for training the model and all our test cases is available via GitHub at https://github.com/bigai-ai/tong-geometry and via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17646188 (ref. 35).

Code availability

Our code and model checkpoints are available via GitHub at https://github.com/bigai-ai/tong-geometry and via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17646188 (ref. 35).

References

Selsam, D. et al. IMO Grand Challenge (IMO Grand Challenge Committee, 2020); https://imo-grand-challenge.github.io/

Polu, S. & Sutskever, I. Generative language modeling for automated theorem proving. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.03393 (2020).

Zheng, K., Han, J. M. & Polu, S. MiniF2F: a cross-system benchmark for formal Olympiad-level mathematics. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2022).

Polu, S. et al. Formal mathematics statement curriculum learning. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2023).

Lample, G. et al. Hypertree proof search for neural theorem proving. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022) (eds Agarwal, A. et al.) 26337–26349 (Curran Associates, 2022).

Achiam, J. et al. GPT-4 technical report. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774 (2023).

Touvron, H. et al. LLaMA: open and efficient foundation language models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.13971 (2023).

Marić, F. et al. Formalizing IMO problems and solutions in Isabelle/HOL. In Proc. Theorem Proving Components for Educational Software 2020 (ThEdu’20) (eds Quaresma, P. et al.) 35–55 (Electronic Proceedings in Theoretical Computer Science (EPTCS), 2020).

Moura, L. d. & Ullrich, S. The Lean 4 theorem prover and programming language. In Proc. Automated Deduction—CADE 28 (eds Platzer, A. & Sutcliffe, G.) 101–121 (Springer, 2021).

Murphy, L. et al. Autoformalizing Euclidean geometry. In Proc. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2024) (ed. Lawrence, N.) 36847–36893 (PMLR, 2024).

Chou, S.-C., Gao, X.-S. & Zhang, J.-Z. An introduction to Geometry Expert. In Proc. International Conference on Automated Deduction (CADE 1996) (ed. Lawrence, N.) 467–471 (Springer, 1996).

Sangwin, C. A brief review of GeoGebra: dynamic mathematics. MSOR Connections 7, 36–38 (2007).

Bak, P., Krajči, S. & Rolínek, M. Automated Generation of Planar Geometry Olympiad Problems. Master’s thesis, Pavol Jozef Šafárik Univ. Košice (2020).

Trinh, T. H., Wu, Y., Le, Q. V., He, H. & Luong, T. Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature 625, 476–482 (2024).

Chervonyi, Y. et al. Gold-medalist performance in solving olympiad geometry with AlphaGeometry2. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03544 (2025).

Guo, D. et al. DeepSeek-Coder: when the large language model meets programming—the rise of code intelligence. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.14196 (2024).

Hoffmann, J. et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2022) (eds Agarwal, A. et al.) 30016–30030 (Curran Associates, 2022).

Sutton, R. S. & Barto, A. G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction 2nd edn (MIT Press, 2018).

Barbu, A. & Zhu, S.-C. Monte Carlo Methods Vol. 35 (Springer, 2020).

Chou, S.-C., Gao, X.-S. & Zhang, J.-Z. A deductive database approach to automated geometry theorem proving and discovering. J. Autom. Reason. 25, 219–246 (2000).

Mackay, J. S. History of the nine-point circle. Proc. Edinb. Math. Soc. 11, 19–57 (1892).

Chen, E. Euclidean Geometry in Mathematical Olympiads Vol. 27 (American Mathematical Society, 2021).

Chen, E. A guessing game: mixtilinear incircles. https://web.evanchen.cc/handouts/Mixt-GeoGuessr/Mixt-GeoGuessr.pdf (2015).

Chen, E. The incenter/excenter lemma. https://web.evanchen.cc/handouts/Fact5/Fact5.pdf (2015).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Proc. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2017) (eds Wallach, H. et al.) 5998–6008 (Curran Associates, 2017).

The Organising Committee and the Problem Selection Committee of IMO 2024 65th International Mathematical Olympiad Problems with Solutions (International Mathematical Olympiad, 2024).

Hilbert, D. The Foundations of Geometry (Open Court Publishing Company, 1902).

Tarski, A. A decision method for elementary algebra and geometry. In Quantifier Elimination and Cylindrical Algebraic Decomposition (eds Caviness, B. F. & Johnson, J. R.) 24–84 (Springer, 1998).

Sicca, V. et al. Newclid: a user-friendly replacement for AlphaGeometry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.11938 (2024).

Sinha, S. et al. Wu’s method can boost symbolic AI to rival silver medalists and AlphaGeometry to outperform gold medalists at IMO geometry. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.06405 (2024).

Schaul, T., Quan, J., Antonoglou, I. & Silver, D. Prioritized experience replay. In Proc. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2016) (eds Bengio, S. & Kingsbury, B.) (ICLR, 2016).

Silver, D. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016).

Silver, D. et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 550, 354–359 (2017).

Silver, D. et al. A general reinforcement learning algorithm that masters chess, shogi, and Go through self-play. Science 362, 1140–1144 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. bigai-ai/tong-geometry. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17646188 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This project is a years-long collaboration between Beijing Institute for General Artificial Intelligence (BIGAI) and Peking University. Along the journey, we would like to thank J. Xie (Winter Camp) and X. Liang (2023 IMO Gold Medalist) for assistance in problem examination, P. Bak (GeoGen author) for very thoughtful and detailed discussion for designing automatic rubrics and generating symmetric proposals, E. Chen (US IMO coach) for assistance in problem evaluation in US Ersatz Math Olympiad, C. Zhen for crafting the beautiful figures, Q. Li and J. Wang for early discussion, L. Xiang and A. Qin for consistent assistance, X. Wang (2024 IMO Gold Medalist) for generated proof assessment and Y. Xu for application implementation. We would like to thank the reviewers for providing constructive feedback to strengthen our work. C.Z., J.S., S.L., Y.L., Y.M., W.W. and S.-C.Z. were supported in part by BIGAI (number KY20220060). All authors were supported in part by the National Science and Technology Major Project (number 2022ZD0114900). Y.M. and Y.Z. were supported in part by the State Key Lab of General AI at Peking University, the PKU-BingJi Joint Laboratory for Artificial Intelligence and the National Comprehensive Experimental Base for Governance of Intelligent Society, Wuhan East Lake High-Tech Development Zone.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Machine Intelligence thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Song, J., Li, S. et al. Proposing and solving olympiad geometry with guided tree search. Nat Mach Intell 8, 84–95 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01164-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-025-01164-x