Main

Achieving net-zero CO2 emissions by mid-century requires rapid development of carbon mitigation measures across multiple sectors, particularly in emission-intensive industries such as power generation and cement production1. According to the International Energy Agency, carbon capture from point emission sources needs to be implemented at a massive scale of 7 gigaton CO2 per year by the year 20502. Nearly half of the emission reductions by 2050 are expected to come from technologies that are still in the prototype or demonstration phase3. Therefore, it is crucial to evaluate how materials and technologies currently available at the prototype scale will contribute to large-scale emission reductions by assuming future projections in their scale and costs. Indeed, only the connection between fundamental research on novel materials and systematic analysis at a large scale can drive further innovations and industrial deployment4.

So far, the large-scale capture demonstrations have relied on chemical absorption where CO2 is dissolved in a solvent: for example, monoethanolamine (MEA)5,6. However, there are several important limitations to the wide-scale adoption of absorption technology7,8. These include high thermal energy consumption for solvent regeneration, strong environmental impact connected to solvent degradation, unavoidable emission of amines, complex infrastructure and large footprint9. These drawbacks reduce MEA-absorption applicability for distributed or space-constrained systems and raise questions regarding long-term viability.

Adsorption-based alternatives have shown promise due to lower regeneration energy and high CO2 selectivity that allows the production of high-purity CO2 even from dilute streams10. Solid sorbents based on metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)4 and amine-functionalized polymers have exhibited high performance11. However, there are several challenges in the view of operation with flue gas, both at material and process levels, including poor sorbent stability in the presence of impurities, performance loss in multiple adsorption-desorption cycles, high pressure drops across the column and reliance on thermal energy12.

Membrane-based processes have emerged as an attractive alternative due to their modularity, environmental compatibility and reliance on electricity rather than thermal input. Membranes offer inherent advantages, as they operate continuously in steady state and without phase changes13. The development of high-performance membranes can yield substantial cost and environmental impact reduction. For coal-fired power plants, MEA absorption has a thermal energy requirement between 2.5 and 3.5 MJth per kilogram CO2 and electricity between 0.3 and 0.75 MJel per kilogram CO2 (ref. 14). By applying thermal-to-electric conversion factors between 15% and 25%, the global equivalent electricity for capture ranges from 0.7 to 1.7 MJel per kilogram CO2 (ref. 15). High-performance-membrane processes have reported electricity requirements below 1 MJel per kilogram CO2 (refs. 16,17,18) while reducing environmental impact and having better economy for small to midscale plants compared to absorption19.

However, the performance of mature membrane technology based on polymeric thin-film composites20 is limited by an intrinsic trade-off between permeability and selectivity21. Techno-economic studies have consistently shown that achieving competitive costs with membranes requires both exceptionally high permeance and selectivity, particularly at low CO2 concentrations. To address this, a range of materials has been developed. Enhancements in polymeric membrane performance are based on the incorporation of inorganic fillers into polymer matrices (mixed-matrix membranes)22 and the addition of CO2-selective carriers (facilitated-transport membranes)23. Inorganic membranes—that is, those based on zeolites24 and carbon molecular sieves25—offer improved performance through rigid, nanoporous structures. Porous graphene membranes have also emerged as a promising class26, offering exceptionally high permeance due to their atom-thick selective layer.

To evaluate the impact of these material innovations at scale, several studies have used process modelling to identify energy- and cost-efficient multistage configurations. These typically combine moderate feed compression with permeate evacuation and are highly sensitive to membrane performance and cost assumptions19,27. Prior analyses have assessed a wide range of technologies28, including commercial polymeric membranes (for example, Polaris16, PolyActive17), polymers of intrinsic microporosity29, mixed-matrix30 and facilitated-transport membranes31,32 and early-stage porous graphene membranes33.

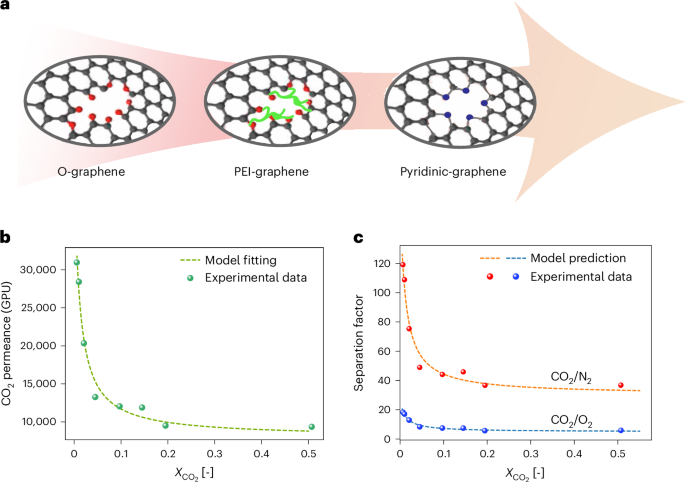

Recent advances in materials chemistry34,35,36 have enabled the development of porous graphene membranes that overcome the trade-off between permeability and selectivity (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Note 1). In particular, pyridinic-nitrogen-functionalized graphene35 exhibits a unique performance trend: both CO2 permeance and CO2/N2 selectivity increase with decreasing feed concentration, contrary to conventional membranes (Fig. 1b,c). This effect, attributed to enhanced CO2 binding at pyridinic N sites, positions these membranes as highly promising for low-concentration separations. These membranes are being scaled up37, field-tested38, and are being commercialized (https://www.divea.ch/) supported by roll-to-roll fabrication techniques39. However, despite their record-high permeation performance, the large-scale economic viability of such membranes, especially under real-world cost uncertainty, remains largely unexplored.

a, Representation of three generations of graphene membranes. b,c, Experimental data and model fitting of (b) CO2 permeance and (c) CO2/N2 and CO2/O2 selectivity as a function of CO2 molar fraction for pyridinic-graphene membranes.

Here we introduce an ex ante technology assessment of porous graphene membrane-based carbon capture and we assess the techno-economic feasibility under scale-up related uncertainties. Our uncertainty-aware analysis indicates that capture processes using high-performance pyridinic-graphene membranes can serve as effective end-of-pipe solutions even for dilute flue gases, such as those from natural gas combined cycle (NGCC) power plants. For coal and cement flue gases, the double-stage process with pyridinic-graphene membranes is competitive with state-of-the-art absorption, adsorption and other membrane processes, while showing marked robustness to scale-up uncertainties.

Results

Future cost projection for the membrane process

Although some membrane technologies have reached commercialization, their large-scale application for post-combustion capture remains limited. As a result, cost projections involve substantial uncertainty, especially for emerging materials such as graphene membranes. Herein, we evaluate the techno-economic feasibility of graphene membrane processes by applying a hybrid approach based on a bottom-up evaluation of the capital cost of the first-of-a-kind (FOAK) plant and a top-down approach to estimate the capital costs of the nth-of-a-kind (NOAK) plant40. These calculations are based on contingency factors and learning rates, for which we define uncertainty ranges. Although the baseline graphene membrane cost is estimated to be US$100 m−2 (Supplementary Note 6), we evaluate a wide range from US$50 m−2 to US$500 m−2, reflecting possible developments in manufacturing. Similarly, we vary electricity prices between US$0.04 per kilowatt-hour and US$0.11 per kilowatt-hour to reflect electricity supply both from the power plant where CO2 is captured (lower price) and from the grid in different geographic locations (US$0.061–0.110 per kilowatt-hour)4. We apply quasirandom Sobol sampling to propagate uncertainties in these parameters across the technical and economic models.

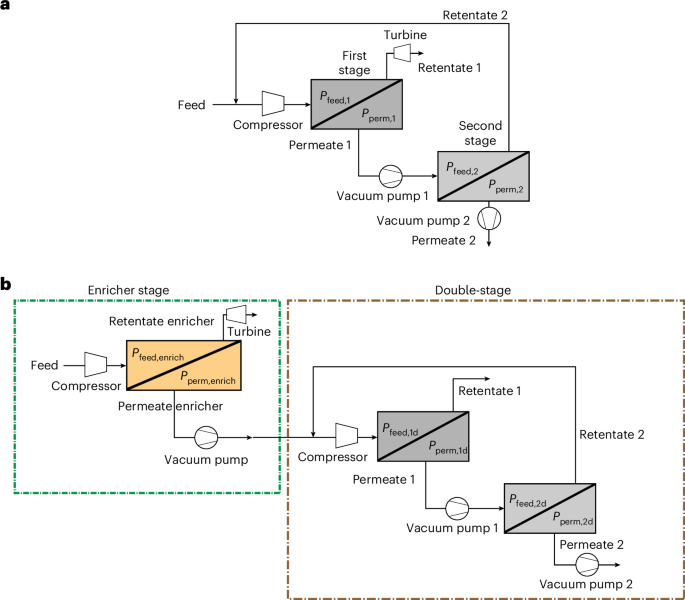

NGCC and NGCC-EGR case study

First, we apply this analysis to NGCC power plants, with and without exhaust gas recycle (EGR). These flue gases are particularly challenging due to low CO2 concentrations (4.0–6.5%). We simulated two membrane processes to be integrated as an end-of-pipe solution: a double-stage process with recycle of retentate 2 and energy recovery via turbo-expander (Fig. 2a), and a triple-stage process composed of an enricher stage and a double stage (Fig. 2b).

a, Double-stage process. b, Triple-stage process. In b, ‘enrich’, ‘1d’ and ‘2d’ refer to the enricher, first stage and second stage of the double-stage process.

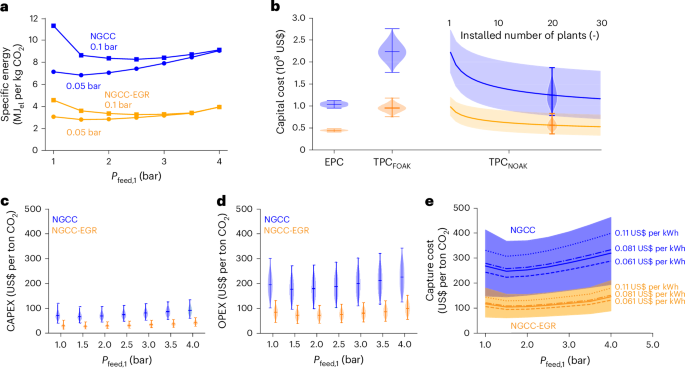

Double-stage is competitive only with EGR

Figure 3 presents the impact of the first-stage pressure ratio on the energy and economics of the double-stage process with pyridinic-graphene membranes (results for polyethylenimine (PEI)-graphene are available in Supplementary Note 7). Lowering the permeate pressure from 0.1 bar to 0.05 bar consistently reduces energy consumption for both NGCC and NGCC-EGR, despite decreased vacuum pump efficiency (50%) at lower suction pressures (Fig. 3a). Across all conditions, specific energy consumption is minimized at a feed pressure between 1.5 bar and 2 bar. Below this range, higher recycle rates are required to maintain recovery and purity targets. Above this range, compression energy dominates.

a, Specific energy as a function of Pfeed,1 with Pperm,1 of 0.05 bar and 0.1 bar. b, Evolution of capital costs from EPC to TPCFOAK and TPCNOAK with variable number of installed plants for a selected pressure configuration: Pfeed,1 = 2 bar, Pperm,1 = 0.05 bar. c,d, CAPEX (c) and OPEX (d) with fixed Pperm,1 = 0.05 bar and variable Pfeed,1. e, Cost confidence intervals in function of Pfeed,1 (continuous line, mean with uncertain electricity cost; dotted lines, mean with fixed electricity costs of US$0.061 per kilowatt-hour, 0.081 per kilowatt-hour and 0.110 US$ per kilowatt-hour). Fixed operating conditions: Pperm,1 = 0.05 bar, Pfeed,2 = 1 bar, Pperm,2 = 0.1 bar, recovery = 90%, purity = 95%. Sampling method: quasirandom Sobol sampling with size n = 6000. Error bars in b–d indicate the mean ± range (min–max). Cost intervals in e between 5th and 95th percentiles.

The evolution of capital costs (Fig. 3b shows one pressure configuration) sees first an escalation of engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) costs. FOAK plants present total plant costs (TPC) higher than EPC costs due to scale-up risks (captured via contingency factors), whereas NOAK plants benefit from cost reductions due to technological learning associated with the increase in the number of installed plants. The confidence interval in EPC is due to the uncertainty in membrane cost, which has a limited impact, especially in the NGCC-EGR case.

In general, capture costs in the NGCC-EGR case show lower sensitivity to uncertainties in membrane and energy cost compared to the base NGCC case, as evident from the charts showing the capital expenditure (CAPEX) and operating expenses (OPEX) (Fig. 3c,d). Figure 3e, where we report the capture cost confidence intervals and highlight the mean costs curves at three fixed values of electricity price, shows that the lowest mean costs (with Pfeed,1 of 1.5 bar and Pperm,1 of 0.05 bar) are around US$250 per ton CO2 for NGCC and US$105 per ton CO2 for NGCC-EGR. These results suggest that the double-stage process with the current membrane performance is economically viable only when EGR is implemented. We also performed an exploratory analysis on improved membrane properties (Supplementary Note 10 and Extended Data Fig. 1) showing that the increase in CO2/O2 selectivity above 16 can make the double-stage process highly competitive even for NGCC.

Triple-stage improves economic feasibility

The configuration in Fig. 2b presents a front-end ‘enricher’ stage, designed to preconcentrate CO2 before a conventional double-stage process. This configuration takes advantage of the unique behaviour of pyridinic-graphene membranes, which are used in the enricher given their high performance at low CO2 concentrations. A hybrid system combining pyridinic-graphene membranes (in the enricher) with PEI-graphene membranes (in the double stage) showed lower energy consumption and costs than the triple-stage systems with PEI-graphene or pyridinic-graphene membranes only (Supplementary Fig. 6).

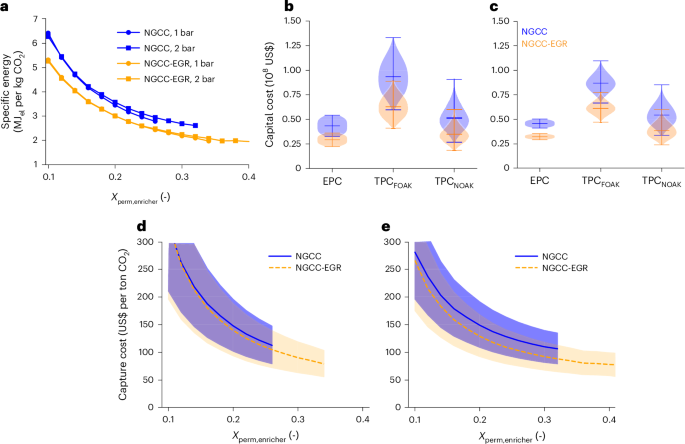

Figure 4 shows the impact of the enricher’s operating conditions on global energy and economics; the pressures in the double stage are kept constant and equal to 2–0.1 bar in the first stage and 1–0.2 bar in the second stage based on cost minimization (Supplementary Note 9).

a, Specific energy as function of the molar fraction of CO2 Xperm,enricher with Pfeed,enricher of 1 bar or 2 bar. b, c, Evolution of capital cost with fixed Pfeed,enricher of 1 bar (b) and 2 bar (c) and the highest Xperm,enricher. d,e, Cost confidence intervals with fixed Pfeed,enricher of 1 bar (d) and 2 bar (e) and variable Xperm,enricher. Fixed operating conditions: P1d, 2–0.1 bar, P2d, 1–0.2 bar, recovery enricher = 90%, recovery and purity double stage = 95%. Sampling method: quasirandom Sobol sampling with size n = 6000. Error bars in b,c, indicate the mean ± range (min–max). Cost intervals in d,e, between 5th and 95th percentiles; line, mean.

The total energy consumption trends at Pfeed,enricher of 1 bar and 2 bar are nearly identical because the higher energy due to compression at 2 bar is offset by the turbine and the more moderate vacuum required on the permeate side (Fig. 4a). Across all conditions, the specific energy decreases monotonically with increasing Xperm,enricher, falling below 3 MJel per kilogram CO2 for NGCC and 2 MJel per kilogram CO2 for NGCC-EGR. This highlights the effectiveness of the enrichment stage in reducing separation work for dilute streams. Importantly, by combining the two membranes and selecting a proper channel thickness, the impact of non-ideal phenomena is limited as minimum specific energy increases by less than 10%, whereas the corresponding specific area increases up to a maximum of 20% (in the NGCC case).

The capital cost trend for this configuration (Fig. 4b,c) shows that higher Pfeed,enricher reduces membrane area requirements and narrows the confidence intervals for EPC and TPCFOAK. TPCNOAK at the two feed pressures are close to each other. As also shown in Fig. 4d,e on total capture costs, the higher enrichment yields a substantial reduction in costs, and the higher pressure improves economic robustness by reducing cost sensitivity to uncertainty (Supplementary Note 8).

Specifically, the optimal mean costs are US$105 per ton CO2 for NGCC (range US$78–133 per ton CO2) and US$77 per ton CO2 for NGCC-EGR (range US$58–97 per ton CO2). These results demonstrate that the triple-stage membrane process offers a more resilient and economically viable solution for CO2 capture from low-concentration flue gas, even under broad uncertainty in technology cost assumptions. The configuration’s ability to deliver robust performance across both NGCC and NGCC-EGR cases highlights its potential for large-scale deployment in the power sector.

Coal power plants and cement plants case study

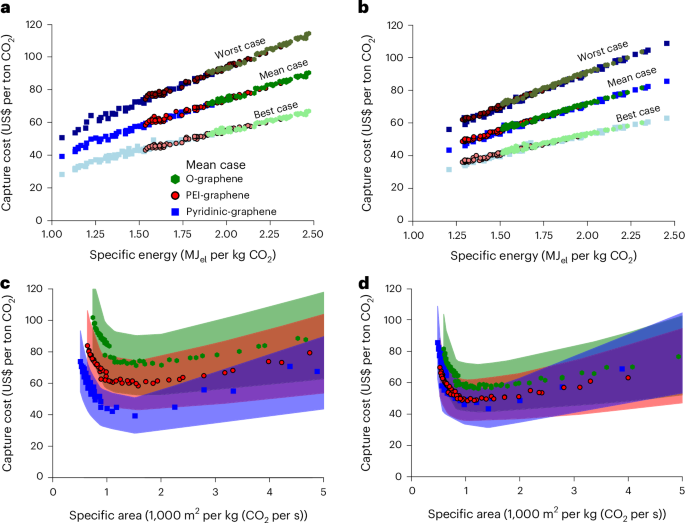

We evaluated the attractiveness of graphene membranes in cost-effective carbon capture from coal and cement plants. In this case, we optimized double-stage configurations (Fig. 2a) with the three different graphene membranes (Fig. 1) across a wide range of operating pressures (Supplementary Notes 11 and 13). To reflect real-world deployment conditions, we performed bi-objective optimization under uncertainty while including non-ideal effects: that is, concentration polarization and pressure drops (Fig. 5).

a–d, Optimized capture cost as function of specific energy (a,b) and specific area (c,d) in the worst-, mean- and best-case scenarios for coal power plants (a,c) and cement plants (b,d) for the three membranes. Sampling method: quasirandom Sobol sampling with size n = 6,000. Cost intervals between 5th (best-case) and 95th (worst-case) percentiles. Measure of the centre: mean.

Capture cost is closely correlated with energy consumption, and membrane area remains relatively small due to the high permeance of all graphene-based membranes. This relationship is especially clear in the cost–energy plots, where configurations with the lowest energy use consistently correspond to the lowest cost across all scenarios. The results are different for the simultaneous optimization of cost and specific area, for which we identify a set of Pareto optimal configurations (for specific area below ~1,500 m2 kg−1 s−1), where the reduction in cost corresponds to an increase in specific area. This is because the reduction in cost can be achieved by reducing the pressure driving force, which is responsible for the energy consumption, at the expenses of the membrane area.

For coal power plants (Fig. 5a,c), pyridinic-graphene membranes yield much lower minimum capture costs than the previous generations of graphene membranes (O-graphene and PEI-graphene membranes; Fig. 1a and Supplementary Note 1). This is primarily due to their much higher CO2/N2 selectivity in the operating range of CO2 concentration (48 for pyridinic-graphene versus 21.3 for O-graphene), which reduces energy demand. Interestingly, the improved permeance of pyridinic-graphene, beyond the already high permeance of O-graphene, has only a marginal effect on the system footprint. Thus, for coal applications, the selectivity of graphene membrane, not the permeance, is the key driver of economic performance (Extended Data Fig. 2). Moreover, pyridinic-graphene membranes show narrower cost confidence intervals, indicating more robust performance under uncertain economic assumptions.

For cement plants (Fig. 5b,d), PEI-graphene and pyridinic-graphene membranes report almost the same minimum cost and energy consumption. In fact, the reduction in energy consumption enabled by the higher CO2/N2 selectivity of pyridinic-graphene membranes is counterbalanced by the increase in energy consumption due to the lower CO2/O2 selectivity (Extended Data Fig. 3). This is attributed to the unique composition of cement flue gas, which contains a higher concentration of oxygen. In such cases, CO2/O2 selectivity becomes critical, as low selectivity leads to increased energy consumption to achieve product purity. As shown in Fig. 1c, CO2/O2 selectivity decreases with increasing CO2 feed concentration, highlighting a performance trade-off that is often overlooked in membrane material design.

Discussion

Optimal process configuration under economic uncertainty

This study demonstrates how recent advances in porous graphene membranes, particularly pyridinic-graphene, enable energy- and cost-efficient CO2 capture across a range of industrial point sources. By combining process modelling in non-ideal conditions with techno-economic analysis under uncertainty, we provide a robust projection of early-stage membrane technology at scale.

For NGCC flue gas, where CO2 concentrations are typically low, we introduce a highly efficient triple-stage process configuration, which includes a front-end ‘enricher’ stage that leverages the enhanced performance of pyridinic-graphene membranes at low CO2 concentrations. Without requiring any modification to the power plant exhaust system, this configuration achieves competitive capture costs, ranging from US$80 per ton CO2 to US$100 per ton CO2, with best-case estimates as low as US$60 per ton CO2, and outperforms conventional double-stage processes in both mean cost and robustness to uncertainty associated with membrane development.

In coal and cement plant applications, where flue gases contain higher CO2 concentrations, we show that advances in membrane technology, from O-graphene to pyridinic-graphene, can reduce capture costs by 30–40%. In the coal case, this is primarily driven by improved CO2/N2 selectivity, which enables energy consumption around 1 MJel per kilogram CO2. In the cement case, we identify CO2/O2 selectivity as a critical factor due to the elevated O2 content in the flue gas. This highlights the importance of tuning membrane properties not only for general performance but also for specific gas compositions.

Pyridinic-graphene allows an end-of-pipe solution for NGCC

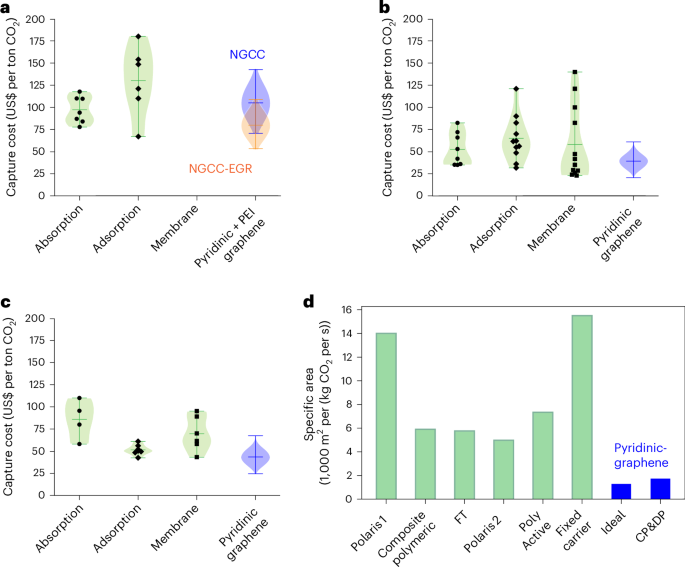

We collected literature cost estimates for absorption, adsorption and membrane processes to build comprehensive cost ranges representative of each technology under different assumptions in material performance, lifetimes and economic parameters (Supplementary Note 16). The cost confidence intervals obtained for pyridinic-graphene membranes via uncertainty analysis are compared with the literature ranges to perform a policy-relevant comparison between technologies across multiple industrial sectors, providing an important contribution to techno-economic benchmarking in the field.

The capture costs for NGCC and NGCC-EGR (Fig. 6a) reported in the literature for the three technologies fall between US$80 per ton CO2 and US$120 per ton CO2. The economic results of the adsorption process have a large variability because many sorbents, especially MOFs, with varying assumptions in costs and lifespans, have been investigated. For example, the lowest value reported in Fig. 6a for a MOF-based temperature swing adsorption process increases from US$70 per ton CO2 to US$100 per ton CO2 and US$170 per ton CO2 when the specific cost of MOF increases from US$0.5 per kilogram to US$15 per kilogram and US$30 per kilogram (ref. 41).

a–c, Capture costs for NGCC and NGCC-EGR power plant (4–6% CO2) (a), coal power plant (13–15% CO2) (b) and cement plant (18–20% CO2) (c) based on literature estimates for absorption, adsorption and membrane processes, and cost ranges with pyridinic-graphene including non-ideal phenomena. d, Coal power plant membrane footprint: bar plot with specific membrane area values from the literature16,28,31,51 and with pyridinic-graphene in the ideal and non-ideal (CP&DP) cases. Sampling method for pyridinic-graphene cost: quasirandom Sobol sampling with size n = 6,000. Error bars in a–c indicate the mean ± range (min–max). FT, facilitated transport.

The literature deems membrane-based capture infeasible as an end-of-pipe solution for NGCC due to low CO2 concentration in the flue gas28. The literature proposed to modify the EGR design by including membrane stages to increase the CO2 concentration in the flue gas from 4% to ~20%. These configurations reported costs between US$75 per ton and US$120 per ton42. We exclude them from comparison in Fig. 6a because they do not represent end-of-pipe solutions. Our results demonstrate that high-performance pyridinic-graphene membranes can achieve competitive costs (US$80–100 per ton CO2, best case US$60–80 per ton CO2 in non-ideal conditions) even in standard post-combustion configurations, with no plant modification required.

Capture costs for coal and cement plant applications

A large number of studies report capture costs for coal-fired power plants, spanning a wide range across absorption, adsorption and membrane technologies (Fig. 6b). Absorption costs are especially scale-dependent, varying substantially with plant size, whereas membrane and adsorption systems exhibit more consistent scaling behaviour14. Another key aspect is the availability and cost of thermal energy, which heavily influences absorption and adsorption costs and varies across industrial contexts. Membranes, by contrast, rely on electricity and can offer greater flexibility in deployment scenarios with limited or expensive heat sources.

Overall, several membrane-based capture studies report costs that outperform the lowest-cost absorption and adsorption benchmarks (Fig. 6b). In our study, pyridinic-graphene membranes yield highly attractive optimized costs under non-ideal conditions, with lower-bound costs comparable to the values reported for other membrane technologies (Fig. 6b). This has been confirmed by applying our costing approach to multiple membranes, as we observed similar best-case scenario costs below US$30 per ton CO2, in line with the literature values. With this approach, we also demonstrated that when uncertainties are taken into account, pyridinic-graphene membranes exhibit the greatest resilience (Supplementary Fig. 20).

For CO2 capture from cement plants flue gas (Fig. 6c), the number of studies is more limited than for NGCC or coal, yet cost estimates for both absorption and membrane processes still vary widely. This variation arises primarily from assumed electricity prices and differences in process configurations and heat recovery systems. Several membrane-based capture processes in the literature report attractive capture costs between US$40 per ton CO2 and US$60 per ton CO2, which are comparable to those of oxyfuel combustion and calcium looping, currently considered leading options for decarbonizing cement production43. In this context, our techno-economic assessment of pyridinic-graphene membranes offers even stronger performance. Capture costs range from US$25 per ton CO2 to US$50 per ton CO2, even under broad cost uncertainty, making these membranes not only cost-competitive but also operationally simpler and more compact compared to high-temperature looping or oxygen-based systems.

Finally, the required feed pretreatment or CO2-rich stream post-treatment depend on the capture technology. In the absorption process, the feed should undergo a pretreatment step to remove impurities (mainly SOx and NOx) that would otherwise lead to a strong degradation of the solvent, resulting in poor capture performance and high energy consumption44. On the contrary, membranes often show high stability even with high content of SO2 and NOx (ref. 45). Graphene-based membranes, with their exceptional chemical stability, are particularly promising in the presence of impurities in the flue gas37. Moreover, the produced high-purity CO2 stream has a different composition depending on the capture process, which impacts the downstream CO2 conditioning and transport via pipeline. Reference 46 compared the cost of the liquefaction following different capture processes and showed that despite the difference in the main impurities post-capture (H2O for absorption, N2 for membranes), the liquefaction costs are very similar.

Process footprint and deployment relevance

Beyond cost, process footprint is increasingly important for carbon-capture adoption, particularly in industrial sites where space restrictions can be critical to the feasibility of the capture technology44. Recent reports on carbon-capture pilot plants based on MTR Polaris membranes with capacity of 20 tons of CO2 per day showed that the membrane system is much more compact than an absorption-based plant with same capacity45,47. Among membrane processes, in Fig. 6d, we compare the specific membrane areas required by graphene membranes, with and without non-ideal phenomena, with those reported for polymeric membranes in the literature. By assuming the same spiral-wound module geometry, the specific membrane area determines the number of modules required for a certain plant capacity and thus the plant footprint. Even accounting for non-idealities, pyridinic-graphene membranes reduce the process footprint by several folds, supporting their use in space-constrained applications such as retrofits or the maritime sector.

Importance of modelling under uncertainty

A central contribution of this study is the inclusion of uncertainty-aware modelling, capturing variability in membrane cost, electricity price, learning rates and contingency factors. We apply probabilistic analysis to both FOAK and NOAK scenarios to generate robust predictions. To demonstrate the robustness of our costing technique, we applied it to other membrane technologies proposed in the literature, and we found that the reported capture costs almost always fall on the lower bound of the confidence intervals obtained with our method (Supplementary Note 17 and Extended Data Fig. 4). This shows the importance of integrating uncertainties to produce ranges of realistic performances that account for the readiness level of the technology. From this comparison under uncertainty, pyridinic-graphene membranes emerge as a robust, scalable and compact solution for carbon capture. This approach improves the credibility of techno-economic projections for early-stage technologies and allows more meaningful comparisons between capture strategies.

Methods

Techno-economic model

An integrated techno-economic model has been developed to simulate, design and optimize multistage membrane processes33. For a given configuration (that is, number and arrangement of the stages), the technical model can be used either to simulate a process with given membrane area, feed and permeate pressures or to design the process able to achieve given targets of CO2 recovery and purity. In this second case (design mode), for given pressures, the membrane areas are calculated by minimizing the error between the calculated and the target values of recovery and purity (design objective function). Then the economic objective function is the total cost of CO2 captured, which is minimized by varying the operating pressures and the configuration.

Technical model

To simulate multistage membrane process, a modular model is developed where the multistage configurations can be described as combinations of a single membrane stage (Supplementary Fig. 2). The single membrane stage has a cross-flow arrangement, characterized by the fact that the permeating gases are collected without mixing in the permeate channel48,49. The cross-flow model has been validated against experimental data for spiral-wound membrane modules50 and used for techno-economic analyses of membrane-based carbon-capture processes17,51,52. Indeed, cross-flow arrangements are often preferred to counterflow arrangement in gas separation because, typically, the improvement in separation performance achieved by a counterflow module does not compensate for the extra cost of fabricating and using these modules, including a sweep flow49.

Non-ideal effects (pressure drops and concentration polarization) are typically assumed to be negligible in the literature. However, these can play an important role in real operations; therefore, all results reported in the main text include non-ideal phenomena.

Single stage with non-ideal phenomena

To model the single stage, the membrane length along the direction of feed stream (z axis) is discretized in a certain number of elements, each with a length dz and an area dA (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To estimate the flux (J) of the component i in the zth discretization element, equation (1) is used. Briefly, Ji is proportional to the partial pressure difference between feed and permeate channel via the permeance Pi. Importantly, in the presence of non-ideal phenomena, the feed pressure varies along the length because of pressure drops, and the driving force depends on the feed concentration at the feed–membrane interface (\({X}_{i,\,f}^{s}\)), which is different than the feed concentration in the bulk (\({X}_{i,\,f}^{b}\)). The effect of concentration polarization is quantified via equation (3)), which depends on the total transmembrane flux (equation (2)) and the mass transfer coefficient k. The definition of the mass transfer coefficient for a spiral-wound membrane module is reported in Supplementary Note 5. The variation of pressure on the feed side is defined via equation (4)), where f is the friction factor (equal to 64/Reynolds), v (m s−1] is the fluid velocity, ρ (kg m−3) is the density and dhydr (m) is the hydraulic diameter of the channel.

Given the cross-current flow arrangement, the flux that crosses the membrane is immediately evacuated, and there is no permeate stream flowing along the length of the module. Therefore, the flux depends on the concentration of the gas immediately after crossing the membrane (X′i, perm). The fluxes are used for mass balances, to assess the variation of flow rates and concentrations of each component along the length of the stage. Equations (5) and (6) represent the total mass balance and the mass balance on the component i in the feed channel, where Qr and Xi,r are the flow rate and the concentration of the retentate produced by the zth element, and Qf and Xi,f are the relevant feed flow rate and concentration. Notably, the feed of each discretization element is given by the retentate produced by the previous element (equations (7) and (8)). The outlet retentate of the single stage is that produced by the last discretization element, and the outlet permeate is given by the sum of those produced in each discretization element (equations (9) and (10)):

$${J}_{i}\left(z\right)={P}_{i}\left({P}_{\mathrm{feed}}\left(z\right){X}_{i,{\rm{f}}}^{{\rm{s}}}\left(z\right)-{P}_{\mathrm{perm}}{X}_{i,\mathrm{perm}}^{{\prime} }\left(z\right)\right)$$

(1)

$${J}_{\mathrm{tot}}\left(z\right)=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{N\mathrm{components}}{J}_{i}\left(z\right)$$

(2)

$$\frac{{X}_{i,\mathrm{perm}}^{{\prime} }\left(z\right)-{X}_{i,{\rm{f}}}^{{\rm{s}}}\left(z\right)}{{X}_{i,\mathrm{perm}}^{{\prime} }\left(z\right)-{X}_{i,{\rm{f}}}^{{\rm{b}}}\left(z\right)}=\exp \left(\frac{{J}_{\mathrm{tot}}\left(z\right)}{k\left(z\right)}\right)$$

(3)

$$\frac{d{P}_{\mathrm{feed}}}{{dz}}=-f\frac{\rho }{2\,{d}_{\mathrm{hydr}}}{v}^{2}$$

(4)

$${Q}_{{\rm{r}}}\left(z\right)={Q}_{{\rm{f}}}\left(z\right)-{J}_{\mathrm{tot}}\left(z\right){dA}$$

(5)

$${X}_{i,{\rm{r}}}\left(z\right){Q}_{{\rm{r}}}\left(z\right)={{X}_{i,{\rm{f}}}^{{\rm{b}}}\left(z\right)Q}_{{\rm{f}}}\left(z\right)-{J}_{i}\left(z\right){dA}$$

(6)

$${Q}_{{\rm{f}}}\left(z+1\right)={Q}_{{\rm{r}}}\left(z\right)$$

(7)

$${X}_{i,{\rm{f}}}^{{\rm{b}}}\left(z+1\right)={X}_{i,{\rm{r}}}\left(z\right)$$

(8)

$${Q}_{\mathrm{perm},\mathrm{out}}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{z=0}^{L}{J}_{\mathrm{tot}}\left(z\right){dA}$$

(9)

$${X}_{i,\mathrm{perm},\mathrm{out}}=\frac{{\sum }_{z=0}^{L}{J}_{i}\left(z\right){dA}}{{Q}_{\mathrm{perm},\mathrm{out}}}$$

(10)

Importantly, although for O-graphene and PEI-graphene membranes the permeance Pi is constant for each component throughout the stage, for pyridinic-graphene membrane we consider PCO2 as a function of the concentration, in line with the experimental evidence. Therefore, we define PCO2 (z) as in equation (11), where \({C}_{{\text{py}}},{k}_{{\text{trans}}}{,\,q}_{{\text{max}}}{,K}_{{\text{eq}}},{P}_{{\text{s}}}\) are constant values reported in Supplementary Note 2:

$${P}_{\mathrm{CO}2}\left(z\right)={C}_{\mathrm{py}}\frac{{k}_{\mathrm{trans}}{q}_{\max }{K}_{\mathrm{eq}}}{1+{K}_{\mathrm{eq}}{P}_{\mathrm{feed}}{X}_{\mathrm{CO}2,{\rm{f}}}\left(z\right)}+\left(1-{C}_{\mathrm{py}}\right){P}_{{\rm{s}}}$$

(11)

The CO2 recovery in a single stage is given by the ratio between the flow rate of CO2 in the outlet permeate and the flow rate in the feed, whereas CO2 purity corresponds to the concentration of CO2 in the permeate. For most applications, a single stage is not enough to achieve the targets of recovery and purity, and multistage processes are needed.

Multistage process

Various configurations can be investigated to improve overall separation performance. The selection of the configuration depends on the permeance and selectivity of the membranes, on the targets of purity and recovery and on the inlet concentration of the feed. For inlet concentrations above 10%, most studies consider a double-stage membrane process with recycle of the retentate stream53. Figure 2a shows the process scheme, where the permeate produced by the first stage is fed to the second stage for further purification, and the retentate produced by the second stage is recycled and mixed with the feed of the first stage to increase driving force. In the first stage, the partial pressure difference is based on the combination of feed compression and permeate under vacuum. Conversely, in the second stage, the feed channel is at ambient pressure and the permeate is under vacuum, because the feed of the second stage has higher concentration and moderate pressure differences are preferable.

When concentration is lower, a triple stage given by an enricher combined with a double-stage process is more suitable to achieve the recovery and purity targets while working at a moderate pressure ratio (Fig. 2b).

Process design with non-ideal phenomena

For any of the investigated membranes, we consider that multiple membrane sheets are wound in multileaf spiral-wound modules, which have a low footprint and allow for an efficient feed distribution, with a packing density reaching up to 2,000 m2 m−3 (ref. 54). In our simulations, each membrane leaf has width (B) of 0.5 m and length (L along the direction of the feed flow) of 0.1 m, whereas the feed channel has thickness (δ) between 100 and 500 µm. The size of the membrane leaf has been selected to be consistent with the membrane sheets currently produced and tested in the laboratory, which we used for model validation. By assuming a spiral-wound module diameter of 20 cm (8 in.) composed of 50 membrane leaves, the membrane area per module amounts to 2.5 m2, corresponding to a packing density of 800 m2 m−3. Large-scale operation will require the use of larger membrane sheets to increase the membrane area per module and reduce the process footprint. For this reason, we performed simulations with larger membrane sheets having a length of up to 0.4 m and a width of 0.9 m, in line with previously reported membranes for spiral-wound modules54. We show that the increase in size has a negligible impact on specific energy and area when the channel thickness is adjusted to reduce pressure drops (Supplementary Note 15). With these dimensions, the membrane area per module and the packing density amount to 18 m2 and 1,400 m2 m−3, respectively, which can be further increased by increasing the number of membrane leaves per module or the size of the single membrane sheet54.

The total number of required modules in parallel depends on the total membrane area. Owing to the high permeance of graphene membranes, the required membrane area is generally small. This allows the use of membrane sheets with a small length without resulting in an unfeasible number of modules. The feed velocity is calculated based on the number of modules, the channel thickness and the width of the membrane sheet. Because the feed velocity has an impact on pressure drops and concentration at the feed–membrane interface, the design process is iterative as feed velocity is updated based on the membrane area required.

Economic model

The economic model calculates the capital and the operating costs. Capital costs are calculated via a hybrid method that combines engineering–economic bottom-up calculations of the FOAK plant and top-down cost projections for the NOAK plant40,55.

Engineering–economic bottom-up calculations

Bottom-up calculations for early-stage technologies are based on the list of the main equipment in the plant, for which we estimate the direct and indirect costs. In the case of membrane-based capture processes, the main pieces of equipment are compressors, blowers, vacuum pumps and membrane modules. We estimated a cost for graphene membranes, including the membrane framework, equal to US$100 per square metre (Supplementary Note 6). This is based on recent commercialization of graphene by roll-to-roll manufacturing process and successful use of low-cost Cu foil (US$10 per square metre) for the production of high-quality graphene for carbon-capture application37. The cost breakdown is elaborated in Supplementary Table 2. However, to take into account the uncertainty related to the production of large-scale membranes, we considered a range of costs between US$50 per square metre and US$500 per square metre. The direct costs, related to the purchase and installation of each equipment, are calculated by referring to specific costs (compressor, vacuum pump and turbine specific costs of US$1,000 per kilowatt, US$870 per kilowatt and US$200 per kilowatt, respectively)56. The direct costs of compressors and vacuum pumps are updated via the Chemical Engineering Plant Cost index57. The indirect costs, including engineering fees, service facilities, buildings and yard improvement, are calculated as 14% of the total direct costs31. The sum of the direct and indirect costs constitutes the total EPC costs.

Next, we calculate the TPC of the FOAK plant starting from the EPC. The escalation of costs from EPC to TPC is due to variations in the design and unforeseen technological issues connected to the upscaling of the technology from lab to the first plant (technology readiness level of 6–8). The cost escalation is based on the application of process and project contingency factors. The process contingency factor varies between 30% and 70% for technologies that are at the concept status with bench-scale data (technology readiness level of 3–4), and the project contingency factor ranges from 30% to 50%. We used these ranges as uncertainty intervals for the Sobol sampling. Finally, we calculated the total capital requirement (TCR) following the IEAGHG approach, by summing the TPC to the owners’ cost (7% of TPC) and the interest during construction58. This last term is estimated assuming that expenditure takes place at the end of each year and that the interest during construction paid in a year is calculated based on the money owed at the end of the previous year (6.4% of TPC considering an interest rate of 8%)59.

Top-down cost projections

The TPC for the NOAK plant is calculated by assuming a technology learning rate Lr and the installed capacity, here expressed in terms of number of installed plants55, as in equations (12) and (13):

$${{TPC}}_{\mathrm{NOAK}}=\mathrm{TCR}{\left(\frac{{{\rm{N}}}_{\mathrm{NOAK}}}{{{\rm{N}}}_{\mathrm{FOAK}}}\right)}^{-b}$$

(12)

$$b=-\frac{\mathrm{ln}\left(1-{L}_{r}\right)}{\mathrm{ln}2}$$

(13)

For our calculations, NFOAK is 1 and refers to a commercial-scale plant coupled with the plant producing the flue gas (see the next section on case studies), and NNOAK is 20. Concerning the learning rate, this is still unknown for carbon-capture technologies. However, previous studies used learning rates from analogous technologies as a proxy40,55. Typical values range from 0.11 (learning rate for flue gas desulphurization) to 0.18 (learning rate for modular technologies such as photovoltaic solar panels). Because the proposed process is given by the combination of early-stage membrane technologies, which are expected to have high learning rates and state-of-the-art compression technologies, we considered a more conservative learning rate of 0.08 as a lower bound and an optimistic learning rate of 0.16 as an upper bound. We used this range for the uncertainty propagation.

The TPCNOAK in US dollars is then annualized by assuming a capital charge factor of 0.125 to calculate the CAPEX (US dollars per year)31.

Operating and total cost

The operating costs consist of the electricity cost, fixed operating costs and cost for membrane replacement. The fixed operating costs include the cost for maintenance and labour and are estimated as 7% per year of the total plant costs56. The membrane replacement costs are calculated by assuming that the membranes are replaced every 5 years60. This lifetime is a conservative assumption, because graphene pores do not irreversibly foul in trace contaminants. Performance loss due to slow pore blockage from contaminants is reversible, and graphene membranes can be regenerated and brought back to their initial performances by heating them for a short time.

Finally, the cost for electricity consumption is calculated by multiplying the specific cost of electricity by the electric power consumption (kW) and the annual operating hours (8,000 hours per year). The cost of electricity varies within an uncertainty range between US$0.04 per kilowatt-hour and US$0.11 per kilowatt-hour. The total electricity consumption is given by the sum of those of compressors and vacuum pumps, estimated as in equation (14) by assuming an adiabatic compression:

$$P\left[W\,\right]=\frac{{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}}{\eta }\frac{\gamma }{\gamma -1}\mathrm{RT}\left[{\left(\frac{{P}_{\mathrm{high}}}{{P}_{\mathrm{low}}}\right)}^{\frac{\gamma -1}{\gamma }}-1\right]$$

(14)

where Qin is the inlet molar flow rate (mol s−1), η (-) is the efficiency, γ is the adiabatic index of the mixture, and Phigh and Plow are the discharge and suction pressures (bar), respectively. η for compressors and blowers is 85%, whereas η for vacuum pumps depends on the suction pressure: it is equal to 70% for suction pressure above 0.1 bar and to 50% for suction pressure below 0.1 bar (ref. 14). For the systems including a turbine, the power recovered by the turbine, Pturbine, is calculated as

$${P}_{\mathrm{turbine}}\left[W\right]={\eta }_{{\rm{t}}}{Q}_{\mathrm{in}}\frac{\gamma }{\gamma -1}\mathrm{RT}\left[{1-\left(\frac{1}{{P}_{\mathrm{in}}}\right)}^{\frac{\gamma -1}{\gamma }}\right]$$

(15)

where ηt is the efficiency of the turbine (90%), Qin (mol s−1) is the total molar flow rate entering the turbine (that is, the total flow rate of the pressurized retentate), and Pin (bar) is the inlet pressure. The power recovered by the turbine is subtracted from the total power to get the net power consumption in the presence of a turbine. We assume that the stream of the retentate leaving the membrane stage is heated before entering the turbine by exchanging heat with the compressed feed stream, which leaves the compressor at temperatures between 100 °C and 130 °C. The increase in temperature up to around 90 °C yields higher power production in the turbine.

The operating costs for energy consumption are subjected to learning rates going from a minimum of 0% to a maximum of 5%, taken in analogy with the observed learning rate for operating costs of oxygen production40. The sum of fixed operating costs, membrane replacement cost and electricity cost is defined as the OPEX in US dollars per year.

The output of the economic analysis is the total capture cost (US dollars per ton CO2), calculated as the sum of CAPEX and OPEX divided by the annual rate of CO2 captured (tons CO2 per year).

Case studies

We optimized capture costs for three case studies corresponding to capture from an NGCC power plant, a coal power plant and a cement plant. This choice was motivated by the need to evaluate the effectiveness of membrane-based capture for diverse emission sources including sources emitting a low concentration of CO2 (NGCC, CO2 concentration of 4%; Supplementary Table 2)4. The capture target was 90% recovery and 95% purity. We considered a feed flow rate of 4,385 mol s−1 (around 390,000 m3 h−1) for all three cases. This corresponded to the production of 0.2 million tons CO2 per year, 0.7 million tons CO2 per year and 0.9 million tons CO2 per year upon capture from NGCC, coal and cement plants, respectively.

Capture from NGCC power plant flue gas is more challenging because the low concentration of CO2 reduces the driving force for separation. To tackle this, the literature proposes to increase CO2 concentration before capture by recirculating a fraction (30–50%) of the exhaust gas back to the gas turbine61,62. This allows an increase in CO2 concentration from 4% to 6.5% and a reduction in flow rate of the flue gas sent to capture63. The variation in the composition of the air sent to the NGCC plant gas turbine due to the exhaust gas recycling can cause a slight decrease in efficiency. However, we did not consider any loss connected to efficiency decrease, in line with previous works, assuming that the design of gas turbines will be improved to take into account variations in inlet air composition55. Therefore, we also considered the composition for NGCC-EGR (35% recycle) in this study (Supplementary Table 2). In this case, the feed flow rate was reduced by 35%.

We designed the process in the presence of the three reported generations of porous graphene membranes. CO2 permeance, CO2/N2 and CO2/O2 selectivity of these membranes are reported in Supplementary Table 1 (Supplementary Note 1). In line with previous experimental data, we took CO2/H2O selectivity equal to 1 for all three membranes36. Pyridinic-graphene is characterized by an attractive increase of permeance and selectivity when the CO2 concentration in the feed decreases (Fig. 1b,c). A gas transport model describing transport across porous graphene fits well the experimental data35 (Supplementary Note 2). CO2/N2 and CO2/O2 selectivity values were calculated considering constant N2 and O2 permeances of 264 GPU and 1,623 GPU, respectively, measured by the experiments (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the ‘Analysis’ and Supplementary Information. The remaining supporting data are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17405824 (ref. 64). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for the cost calculation under uncertainty is available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17405824 (ref. 64).

References

Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (IPCC, 2022).

Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector (IEA, 2021).

Kearns, D., Liu, H. & Consoli, C. Technology Readiness and Costs of CCS (Global CCS Institute, 2021).

Charalambous, C. et al. A holistic platform for accelerating sorbent-based carbon capture. Nature 632, 89–94 (2024).

Nessi, E., Papadopoulos, A. I. & Seferlis, P. A review of research facilities, pilot and commercial plants for solvent-based post-combustion CO2 capture: packed bed, phase-change and rotating processes. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 111, 103474 (2021).

Vega, F. et al. Current status of CO2 chemical absorption research applied to CCS: towards full deployment at industrial scale. Appl. Energy 260, 114313 (2020).

de Meyer, F. & Jouenne, S. Industrial carbon capture by absorption: recent advances and path forward. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 38, 100868 (2022).

Wang, M., Joel, A. S., Ramshaw, C., Eimer, D. & Musa, N. M. Process intensification for post-combustion CO2 capture with chemical absorption: a critical review. Appl. Energy 158, 275–291 (2015).

Giordano, L., Roizard, D. & Favre, E. Life cycle assessment of post-combustion CO2 capture: a comparison between membrane separation and chemical absorption processes. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 68, 146–163 (2018).

Hong, W. Y. A techno-economic review on carbon capture, utilisation and storage systems for achieving a net-zero CO2 emissions future. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 3, 100044 (2022).

Young, J., García-Díez, E., Garcia, S. & Van Der Spek, M. The impact of binary water-CO2isotherm models on the optimal performance of sorbent-based direct air capture processes. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5377–5394 (2021).

Farmahini, A. H., Krishnamurthy, S., Friedrich, D., Brandani, S. & Sarkisov, L. Performance-based screening of porous materials for carbon capture. Chem. Rev. 121, 10666–10741 (2021).

Chen, S., Liu, J., Zhang, Q., Teng, F. & McLellan, B. C. A critical review on deployment planning and risk analysis of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) toward carbon neutrality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 167, 112537 (2022).

Zanco, S. E. et al. Postcombustion CO 2 capture: a comparative techno-economic assessment of three technologies using a solvent, an adsorbent, and a membrane. ACS Eng. Au 1, 50–72 (2021).

Rao, A. B. & Rubin, E. S. A technical, economic, and environmental assessment of amine-based CO2 capture technology for power plant greenhouse gas control. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36, 4467–4475 (2002).

Merkel, T. C., Lin, H., Wei, X. & Baker, R. Power plant post-combustion carbon dioxide capture: an opportunity for membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 359, 126–139 (2010).

Giordano, L., Roizard, D., Bounaceur, R. & Favre, E. Evaluating the effects of CO2 capture benchmarks on efficiency and costs of membrane systems for post-combustion capture: a parametric simulation study. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 63, 449–461 (2017).

Favre, E. Membrane separation processes and post-combustion carbon capture: state of the art and prospects. Membranes (Basel) 12, 884 (2022).

Hasan, M. M. F., Baliban, R. C., Elia, J. A. & Floudas, C. A. Modeling, simulation, and optimization of postcombustion CO2 capture for variable feed concentration and flow rate. 1. Chemical absorption and membrane processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 15642–15664 (2012).

Brinkmann, T. et al. Pilot scale investigations of the removal of carbon dioxide from hydrocarbon gas streams using poly (ethylene oxide)-poly (butylene terephthalate) PolyActiveTM) thin film composite membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 489, 237–247 (2015).

Robeson, L. M., Dose, M. E., Freeman, B. D. & Paul, D. R. Analysis of the transport properties of thermally rearranged (TR) polymers and polymers of intrinsic microporosity (PIM) relative to upper bound performance. J. Memb. Sci. 525, 18–24 (2017).

Galizia, M. et al. 50th anniversary perspective: polymers and mixed matrix membranes for gas and vapor separation: a review and prospective opportunities. Macromolecules 50, 7809–7843 (2017).

Zhang, Z., Rao, S., Han, Y., Pang, R. & Ho, W. S. W. CO2-selective membranes containing amino acid salts for CO2/N2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 638, 119696 (2021).

Makertihartha, I. G. B. N. et al. Silica supported SAPO-34 membranes for CO2/N2 separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 298, 110068 (2020).

Kumar, R., Zhang, C., Itta, A. K. & Koros, W. J. Highly permeable carbon molecular sieve membranes for efficient CO2/N2 separation at ambient and subambient temperatures. J. Memb. Sci. 583, 9–15 (2019).

Huang, S. et al. Single-layer graphene membranes by crack-free transfer for gas mixture separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–11 (2018).

Arias, A. M. et al. Optimization of multi-stage membrane systems for CO2 capture from flue gas. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 53, 371–390 (2016).

He, X., Chen, D., Liang, Z. & Yang, F. Insight and comparison of energy-efficient membrane processes for CO2 capture from flue gases in power plant and energy-intensive industry. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2, 100020 (2022).

Ferrari, M. C., Bocciardo, D. & Brandani, S. Integration of multi-stage membrane carbon capture processes to coal-fired power plants using highly permeable polymers. Green. Energy Environ. 1, 211–221 (2016).

Budhathoki, S., Ajayi, O., Steckel, J. A. & Wilmer, C. E. High-throughput computational prediction of the cost of carbon capture using mixed matrix membranes. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1255–1264 (2019).

Han, Y. & Ho, W. S. W. Design of amine-containing CO2-Selective membrane process for carbon capture from flue gas. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 5340–5350 (2020).

Hussain, A. & Hägg, M. B. A feasibility study of CO2 capture from flue gas by a facilitated transport membrane. J. Memb. Sci. 359, 140–148 (2010).

Micari, M., Dakhchoune, M. & Agrawal, K. V. Techno-economic assessment of postcombustion carbon capture using high-performance nanoporous single-layer graphene membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 624, 119103 (2021).

Hsu, K. J. et al. Multipulsed millisecond ozone gasification for predictable tuning of nucleation and nucleation-decoupled nanopore expansion in graphene for carbon capture. ACS Nano 15, 13230–13239 (2021).

Hsu, K.-J. et al. Graphene membranes with pyridinic nitrogen at pore edges for high-performance CO2 capture. Nat. Energy 9, 964–974 (2024).

Huang, S. et al. Millisecond lattice gasification for high-density CO2- And O2-sieving nanopores in single-layer graphene. Sci. Adv. 7, 1–13 (2021).

Hao, J. et al. Scalable synthesis of CO2-selective porous single-layer graphene membranes. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2, 241–251 (2025).

Agrawal, K. V. & Bautz, R. Capture du carbone par membranes en graphène à nanopores. Aqua & Gas https://www.aquaetgas.ch/fr/%C3%A9nergie/gaz/20220225_capture-du-carbone/ (2022).

Breakthrough in roll-to-roll CVD graphene polymer composites. General Graphene https://generalgraphenecorp.com/breakthrough-in-roll-to-roll-cvd-graphene-polymer-composites/(2023).

Young, J. et al. The cost of direct air capture and storage can be reduced via strategic deployment but is unlikely to fall below stated cost targets. One Earth 6, 899–917 (2023).

Yancy-Caballero, D. et al. Isotherm modeling and techno-economic analysis of a TSA moving bed process using a tetraamine-appended MOF for NGCC applications. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 128, 103957 (2023).

Gatti, M. et al. Preliminary performance and cost evaluation of four alternative technologies for post-combustion CO2 capture in natural gas-fired power plants. Energ. (Basel) 13, 543 (2020).

Gardarsdottir, S. O. et al. Comparison of technologies for CO 2 capture from cement production—Part 2: Cost analysis. Energies 12, 542 (2019).

Roussanaly, S. et al. Towards improved cost evaluation of carbon capture and storage from industry. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 106, 103263 (2021).

Batoon, V. et al. In Proc. 16th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, GHGT-16 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4281208 (IEAGHG, 2022).

Deng, H., Roussanaly, S. & Skaugen, G. Techno-economic analyses of CO2 liquefaction: impact of product pressure and impurities. Int. J. Refrig. 103, 301–315 (2019).

Breen, A. et al. Large pilot testing of MTR’s membrane-based post-combustion CO2 capture process. In Proc. 17th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, GHGT-17 https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5070818 (IEAGHG, 2024).

Pan, C. Y. Gas separation by high-flux, asymmetric hollow-fiber membrane. AlChE J. 32, 2020–2027 (1986).

Baker, R. W. Membrane Technology and Applications (Wiley, 2012).

Han, Y., Salim, W., Chen, K. K., Wu, D. & Ho, W. S. W. Field trial of spiral-wound facilitated transport membrane module for CO2 capture from flue gas. J. Memb. Sci. 575, 242–251 (2019).

Xu, J. et al. Post-combustion CO2 capture with membrane process: practical membrane performance and appropriate pressure. J. Memb. Sci. 581, 195–213 (2019).

Han, Y. & Ho, W. S. W. Facilitated transport membranes for H2 purification from coal-derived syngas: a techno-economic analysis. J. Memb. Sci. 636, 119549 (2021).

Chatziasteriou, C. C., Kikkinides, E. S. & Georgiadis, M. C. Recent advances on the modeling and optimization of CO 2 capture processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 165, 107938 (2022).

Yang, Y. et al. A commercial-size prototype of countercurrent spiral-wound membrane module for flue gas CO2 capture. J. Memb. Sci. 696, 122520 (2024).

van der Spek, M., Ramirez, A. & Faaij, A. Challenges and uncertainties of ex ante techno-economic analysis of low TRL CO2 capture technology: lessons from a case study of an NGCC with exhaust gas recycle and electric swing adsorption. Appl. Energy 208, 920–934 (2017).

Roussanaly, S., Anantharaman, R., Lindqvist, K., Zhai, H. & Rubin, E. Membrane properties required for post-combustion CO2 capture at coal-fired power plants. J. Memb. Sci. 511, 250–264 (2016).

Turton, R., Bailie, R. C., Whiting, W. B., Shaeiwitz, J. A. & Bhattacharyya, D. Analysis, Synthesis, and Design of Chemical Processes (Prentice Hall, 1998).

Rubin, E. S. et al. A proposed methodology for CO2 capture and storage cost estimates. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 17, 488–503 (2013).

Davison, J. Criteria for Technical and Economic Assessment of Plants With Low CO2 Emissions (IEAGHG, 2009).

Roussanaly, S., Lindqvist, K., Anantharaman, R. & Jakobsen, J. A systematic method for membrane CO2 capture modeling and analysis. Energy Procedia 63, 217–224 (2014).

Sipöcz, N. & Tobiesen, F. A. Natural gas combined cycle power plants with CO2 capture - opportunities to reduce cost. Int. J. Greenh. Gas. Control 7, 98–106 (2012).

Mores, P. L., Godoy, E., Mussati, S. F. & Scenna, N. J. A NGCC power plant with a CO2 post-combustion capture option. Optimal economics for different generation/capture goals. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 92, 1329–1353 (2014).

Díaz-Herrera, P. R., Alcaraz-Calderón, A. M., González-Díaz, M. O. & González-Díaz, A. Capture level design for a natural gas combined cycle with post-combustion CO2 capture using novel configurations. Energy 193, 116769 (2020).

Micari, M., Hsu, K.-J., Bempeli, S. & Agrawal, K. V. Source data and code for ‘Energy- and cost-efficient CO2 capture from dilute emissions by pyridinic-graphene membranes’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17405824 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge our host institution EPFL (Solutions4Sustainability CCUS Project, K.V.A. and M.M.), SNSF (Ambizione grant no. 223517, M.M.) and the Canton of Valais for supporting the project. We also acknowledge J. A. Schiffmann for the valuable discussions on the technical and economic modelling of energy recovery devices.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.V.A. is a cofounder of a startup looking to commercialize porous graphene membranes for carbon capture. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Sustainability thanks Xuezhong He, Mijndert van der Spek and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Exploratory analysis on the impact of membrane properties on minimum energy for dilute streams.

(Top) Bar charts with minimum specific energy of four membrane process configurations with variable CO2/N2 and CO2/O2 selectivity. (Bottom) Percentage difference between minimum specific energy values found for the double stage and the triple stage system with turbine. The colorbar refers to the minimum specific energy of the double stage in ideal conditions.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Optimized processes with and without non-ideal phenomena for coal power plant flue gas.

Top row: curves of specific energy vs. specific area for a double stage process with O-graphene, PEI-graphene and Pyridinic-graphene membranes in the ideal (left) and non-ideal (right) case. The colorbar refers to the mean capture costs. Bottom row: Pressures corresponding to the minimum capture cost with O-graphene, PEI-graphene and pyridinic-graphene membranes in the best-case (5th percentile), mean case and worst-case (95th percentile) scenario with the relevant costs in the ideal (left) and non-ideal (right) case. Fixed operating conditions: Qfeed = 4385 mol/s, Xfeed,CO2 = 0.135, Pfeed,2 = 1 bar, Pperm,2 = 0.2 bar, recovery = 90%, purity = 95%. Sample size n = 6000.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Optimized processes with and without non-ideal phenomena for cement plant flue gas.

Top row: curves of specific energy vs. specific area for a double stage process with O-graphene, PEI-graphene and Pyridinic-graphene membranes in the ideal (left) and non-ideal (right) case. The colorbar refers to the mean capture costs. Bottom row: Pressures corresponding to the minimum capture cost with O-graphene, PEI-graphene and pyridinic-graphene membranes in the best-case (5th percentile), mean case and worst-case (95th percentile) scenario with the relevant costs in the ideal (left) and non-ideal (right) case. Fixed operating conditions: Qfeed = 4385 mol/s, Xfeed,CO2 = 0.18, Pfeed,2 = 1 bar, Pperm,2 = 0.2 bar, recovery = 90%, purity = 95%. Sample size n = 6000.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Cost confidence intervals for various membrane technologies.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Experimental data of pyridinic-graphene membranes at variable CO2 concentration.

Source Data Fig. 3

Process performance data for double-stage system with pyridinic-graphene membranes for NGCC and NGCC-EGR case study.

Source Data Fig. 4

Process performance data for triple-stage system with pyridinic- and PEI-graphene membranes for NGCC and NGCC-EGR case study.

Source Data Fig. 5 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3

Process performance data for double-stage system with the three generations of graphene membranes for coal power plant and cement plant case study.

Source Data Fig. 6

Literature values of capture cost for absorption, adsorption and membrane technologies and the three case studies.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Operating conditions for minimum energy with variable process configurations and membrane properties.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Process performance data for double-stage processes with other membrane technologies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Micari, M., Hsu, KJ., Bempeli, S. et al. Energy- and cost-efficient CO2 capture from dilute emissions by pyridinic-graphene membranes. Nat Sustain (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01696-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-025-01696-5