Introduction

Smoking is a significant risk factor for a range of health outcomes and remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States1. Smoking increases the risk of developing lung2, breast3, head and neck4, pancreatic5, and other cancers6. Among cancer patients, continued smoking after diagnoses has been associated with higher risks of recurrence and second malignancies7 as well as increased overall and cancer-specific mortality1. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has established lung cancer screening guidelines that determine eligibility based on individuals’ smoking history. The 2013 USPSTF criteria recommend annual low-dose CT screening for adults aged 55–80 years with a ≥ 30 pack-year smoking history (e.g., one pack/day for 30 years) who currently smoke or quit within the past 15 years8. In 2021, the USPSTF expanded eligibility to ages 50-80 and lowered the threshold to 20 pack-years while maintaining the 15-year quit limit, broadening access to screening for high-risk populations9. Given the impact of smoking on various health outcomes, obtaining accurate smoking history data is crucial for effective risk assessment, cancer screening eligibility decisions, and monitoring health outcomes in patients.

Electronic Health Records (EHRs) provide excellent opportunities to collect smoking information; however, capturing reliable and comprehensive smoking history has been challenging10. Previous studies have documented significant data quality issues. For example, 32% of patients had inconsistencies in the documented smoking status, and over half of smoking status changes were implausible (including implausible changes and loss of information changes)10. While basic smoking variables such as smoking status (current, former or never) are typically recorded in structured EHR fields, most detailed information such as smoking pack-years, duration, and quit-years are often found in clinical notes only11,12. Clinical notes could be an informative source for obtaining smoking-related information compared to structured data fields alone13. Several prior studies have proposed various natural language processing (NLP) algorithms for extracting key smoking-related variables from clinical notes in various healthcare settings14,15,16,17,18. Common approaches include keyword extraction through various algorithms (e.g., two-layer rule-engine14, text similarity18), deep learning models for sentence classification16,18, and development of filtering pipelines to identify relevant clinical notes17. However, all approaches relied on single-institution datasets without cross-system validation, limiting generalizability.

More recently, large language models (LLMs) have become powerful tools for clinical information extraction. In particular, fine-tuned transformer models (e.g., BERT variants) show strong performance for extracting smoking history19. GPT-based approaches likewise achieve high accuracy in identifying substance-use status (including tobacco) from clinical notes20,21. Scoping reviews across clinical domains document the growing use of fine-tuning and prompt-engineering, with generally positive results, though performance varies by model type and task22. However, these existing LLM-based studies for smoking mainly focused on note-level extraction (single time point), lacking performance evaluation in longitudinal settings23. When comparing data from many clinical sources over different time periods, individuals’ smoking trajectories show frequent inconsistencies10,24,25, making it crucial to account for longitudinal smoking histories. Furthermore, most existing studies have relied on single-source data or publicly available de-identified datasets such as the MIMIC23, a widely-used emergency medicine and critical care database, without validation across independent healthcare systems. Moreover, despite recognizing LLM hallucinations26,27 as a source of error, prior works have not proposed any systematic mechanisms for identifying or correcting such errors across time points—limiting the clinical reliability of extracted smoking histories23.

In this study, we develop a framework leveraging LLMs and rule-based smoothing to extract and harmonize longitudinal smoking data. This framework enables automated extraction of comprehensive smoking histories (including smoking status, pack-years, quit-years, duration) from clinical notes in EHRs across different healthcare systems (academic and community-based healthcare systems). We evaluated note-level accuracy across multiple smoking variables, implemented longitudinal data smoothing methods to resolve common inconsistencies and validated the proposed approach across both academic and community-based healthcare settings. We then demonstrated the utility of this enhanced longitudinal smoking data curation in evaluating various post-treatment surveillance strategies for lung cancer patients.

Results

Patient characteristics

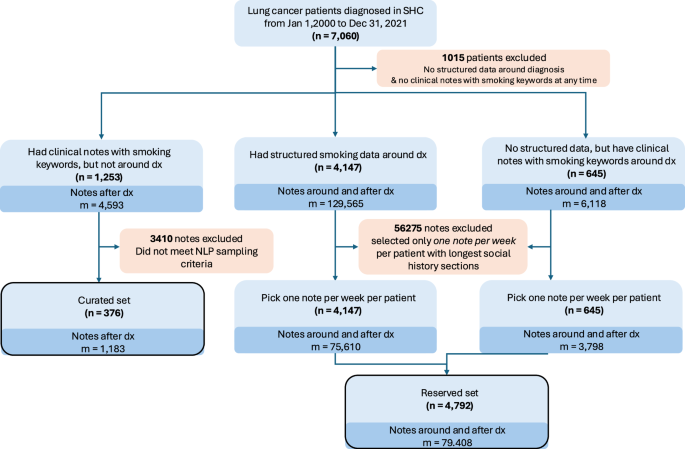

The Stanford Healthcare (SHC) cohort used for LLM development and evaluation included 376 lung cancer patients (49.7% female, median age 65.9 years) with 1,183 clinical notes that were manually annotated (i.e., chart reviewed) for smoking history information (Supplemental Table 1; Figs. 1, 2). The cohort was predominantly White (54.8%) and Asian (16.8%). Most patients had adenocarcinoma (47.3%), with 43.9% early-stage lung cancer and 38.3% advanced-stage disease. Common first-course treatments included chemotherapy (56.9%) and radiotherapy (45.5%) (Supplemental Table 1). The patients in this cohort had a median of 2 notes (IQR: 1–3), and with a median of 17.1 months (IQR: 6.4–37.5) from diagnosis to note date.

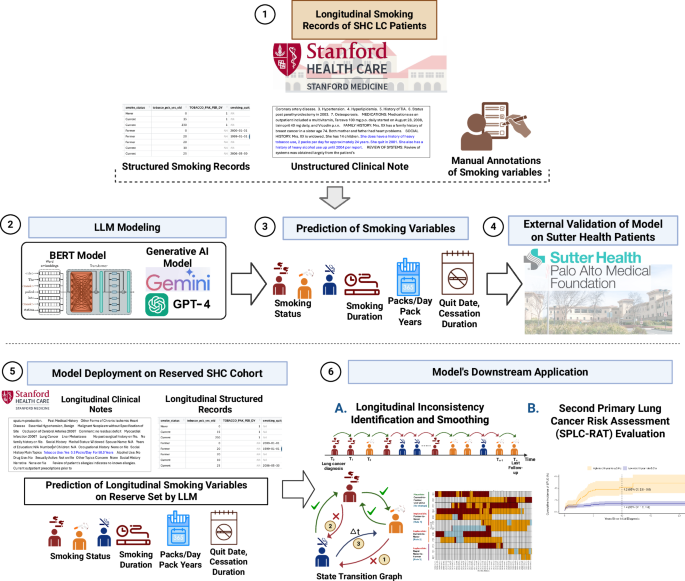

The study workflow is organized into six key components. (1) Longitudinal structured and unstructured EHRs from 376 LC patients at SHC are curated. Manual annotations of 1,183 unstructured clinical notes are performed to enable LLM model training. (2) LLMs including BERT-based models (ClinicalBERT) and generative AI models (Gemini, PALM, and GPT) are trained using prompt-based learning to extract key smoking-related variables. (3) The trained generative AI models (Gemini 1.5 Flash and GPT-4) predict key smoking variables: smoking status, smoking duration, packs per day or pack-years, and cessation indicators such as quit date and cessation duration. (4) External validation of the models is performed on an independent cohort of 142 LC patients from Sutter Health (500 clinical notes). (5) The trained model is deployed on a reserved SHC cohort of 4792 LC patients (79,408 longitudinal notes). (6) The predicted longitudinal smoking history is used in two downstream analyses: A. Identification and smoothing of inconsistencies in smoking status across time points using state transition modeling, and B. Evaluation of lung cancer patients’ eligibility and temporal risk profiles using the Second Primary Lung Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (SPLC-RAT). Created in BioRender. Khan, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/y9n56i6. LLM Large Language Model; LC Lung Cancer; EHR Electronic Health Record; SHC Stanford Health Care; GPT-4 Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4; SPLC-RAT Second Primary Lung Cancer Risk Assessment Tool.

Diagram for Selection of Cohort and Clinical Notes Used for Large Language Models Development (N = 376: Curated set) and for Evaluating Surveillance Strategies among Lung Cancer Survivors (N = 4792: Reserved set) at Stanford Health Care. *LC: Lung cancer, SHC: Stanford Health Care **Note selection sampling method is described in Methods and Supplemental Table 7.

Performance and validation of LLM models in smoking data extraction

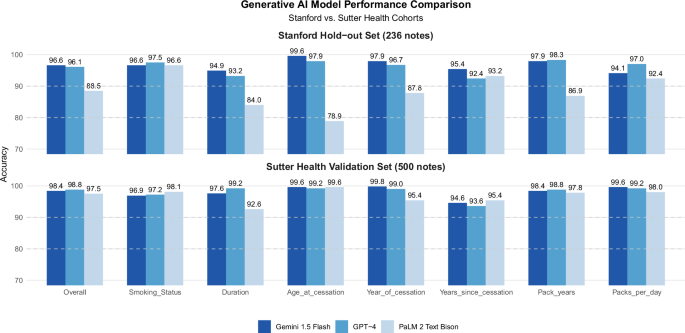

Using zero-shot prompting, generative LLMs (Gemini 1.5 Flash, GPT-4, PALM 2 TextBison) outperformed BERT-based models (ClinicalBERT, blueBERT) in extracting smoking status from clinical notes. Generative LLMs (Gemini 1.5 Flash, GPT-4, PALM 2 TextBison) outperformed end-to-end fine-tuned BERT based models (ClinicalBERT, BlueBERT), with significantly higher accuracy (the range of 96.6% to 97.5% for generative LLMs vs. 76.9% to 82.5% for BERT-based models) (Supplemental Fig. 1). Based on this superior performance, we focused on generative LLMs for extracting all smoking variables using the same zero-shot prompting approach. Among the generative models, Gemini 1.5 Flash and GPT-4 demonstrated the highest overall accuracy (96.6% and 96.1%) across all seven smoking variables (Fig. 3). Among these variables, age at cessation (78.9–99.6%) exhibited the best performance, followed by pack-years (86.9–98.3%) and year of cessation (87.8–97.9%), while years since cessation (92.4–95.4%) and smoking duration (84.0–94.9%) showed slightly lower accuracy. When we validated these models using an independent dataset of 500 clinical notes (from 142 patients) in a community-based healthcare setting at Sutter Health (Supplemental Table 2), which included notes with sparse smoking information, Gemini 1.5 Flash and GPT-4 maintained similarly high overall accuracy (98.4% and 98.9% respectively) (Fig. 3). Notably, accuracy improved for smoking duration (97.6–99.2%) and packs per day (99.2–99.6%) in the validation data compared to the development data at SHC, demonstrating the generalizability of these LLMs across different healthcare systems and documentation quality levels (Fig. 3).

Comparative performance of three generative AI models (Gemini 1.5 Flash, GPT-4, and PaLM 2 Text Bison) for smoking variable extraction using Stanford hold-out test set (236 notes) and Sutter Health external validation cohort (500 notes).

Error analysis identified the specific areas where the generative LLM (Gemini) struggled, such as interpreting approximate dates, distinguishing between historical and current smoking behaviors, and handling complex smoking histories with multiple quit attempts (Supplemental Table 3). Poor note quality, such as overly brief documentation (e.g., “Social history: Tobacco use” with no indication whether current, former, or never smoker) and contradictory information (e.g., same note stating “Former smoker, quit 2019” and “Current smoker, 1 pack per day”), also hindered smoking information extraction. Notably, LLMs handled grammar, spelling, punctuation errors, and clinical abbreviations very well.

Deployment of Gemini for large-scale longitudinal smoking data curation

To curate comprehensive longitudinal smoking data, we deployed Gemini 1.5 Flash to extract smoking information from 79,408 clinical notes of a larger lung cancer cohort at SHC. This cohort included lung cancer patients who has at least one smoking related records (either clinical notes or structured data) at the time of diagnosis (N = 4792; Supplemental Table 4). The cohort had a median diagnosis age of 69.1 years (IQR: 61.3–75.8) and was predominantly White (58.1%) and Asian (24.2%) (Supplemental Table 4). Within this cohort, 55.1% were former smokers, 17.4% current smokers, and 27.6% never smokers at the time of diagnosis (Supplemental Table 5). The curated longitudinal smoking data (based on 79,408 clinical notes and 57,407 structured data) showed that 92.7% of patients had multiple (≥2) smoking-related clinical notes or structured smoking data, with a median follow-up of 2.9 years (IQR: 0.6–6.3 years) after the initial diagnosis. Each patient had a median of 14 smoking records (IQR: 5–37) over up to 22.4 years from the initial diagnosis (Supplemental Table 5).

Identifying and resolving inconsistencies in longitudinal smoking data

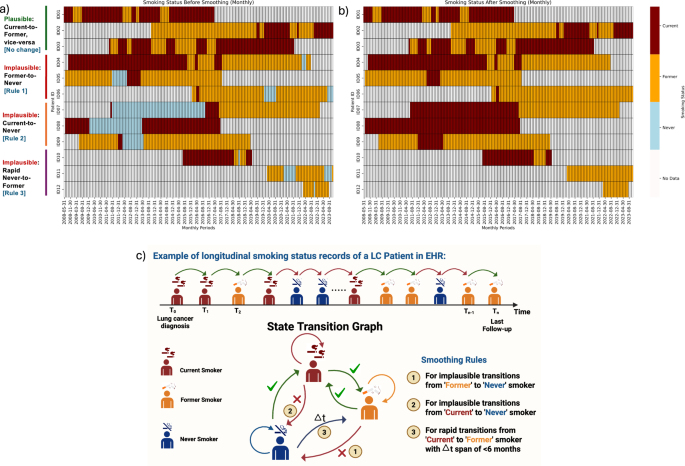

Integration of LLM-extracted (using Gemini) and structured smoking records revealed inconsistencies in how smoking status changed over time within patient longitudinal smoking histories (Fig. 4a). For example, some patients (e.g., Patient ID = 5 or ID = 6) change their smoking status from “former” to “never,” which is implausible and should not occur (Fig. 4c). Overall, 18.0% (n = 862 patients) had at least one “implausible” transition in their smoking status, and 14.7% (n = 703 patients) had two or more implausible transitions in longitudinal smoking status (Supplemental Table 6). We developed and applied rule-based smoothing methods that utilize each person’s longitudinal smoking status, pack-years data, and quit years to identify most plausible transitions for smoking status. The smoothed smoking status trajectories of the example patients are shown in Fig. 4b. After applying the rule-based smoothing methods, the implausible transitions were corrected, producing accurate smoking histories for the study cohort.

The below heatmaps illustrate the transitions in smoking status of patients over time, delineated into “before” (the left panel a) and “after” (the right panel b) applying the proposed rule-based smoothing corrections. Each row in both heatmaps represents a unique patient, and each column corresponds to sequential time points (monthly) at which smoking statuses were recorded. The colors used in the heatmaps indicate specific statuses: ‘No Data’ (off-white), ‘Never’ (light blue), ‘Former’ (orange), and ‘Current’ (maroon). c The schematic diagram of smoking status changes. The upper section of the figure visually represents longitudinal smoking status data for a patient who initially presented as a current smoker, then transitioned to a former smoker, and subsequently to a never smoker—a change that is considered implausible. The state transition graph (lower section) presents plausible versus implausible smoking status changes that informed the development of the rule-based smoothing method. Created in BioRender. Khan, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ogaiozq.

Utility of longitudinal smoking history data in evaluating post-diagnosis surveillance strategies in lung cancer patients

We evaluated the utility of the curated longitudinal smoking data for lung cancer patients in monitoring their long-term outcomes following the initial diagnosis. Recognizing that smoking is a known risk factor for developing second primary lung cancer (SPLC), we examined the proportion of patients in the SHC cohort who continued smoking after their lung cancer diagnosis and remained as current smokers over time (Supplemental Fig. 3). The result showed that the current smoking rate decreased substantially from 17.4% at initial diagnosis to 7.7% at landmark year 5 (i.e., 5 years after the initial diagnosis) among the 1113 patients who remained alive and free of SPLC throughout the five-year period.

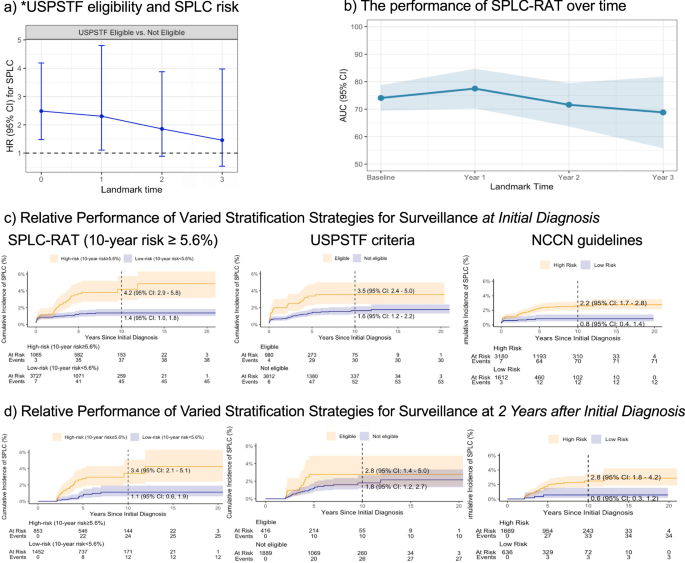

Building upon on prior studies28,29 that examined the 2013-USPSTF lung cancer screening criteria—based on smoking history and age—to predict the subsequent risk of developing SPLC in lung cancer patients, we reproduced this association (Fig. 5a). The USPSTF screening eligibility evaluated at the initial diagnosis was significantly associated with the SPLC risk (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.76; p = 0.019). However, the magnitude of this association decreased over time when using updated patients’ smoking information (Fig. 5a), a trend not observed in previous studies28,29 due to their lack of longitudinal smoking data; this underscores that smoking alone may not fully capture SPLC risk when considering full longitudinal smoking data that reflects changes in patients’ smoking behavior after the diagnosis. When examining the 2013-USPSTF criteria using raw extracted data without rule-based smoothing, the associations exhibited wider confidence intervals and no significant association (Supplemental Fig. 4), even at the time of diagnosis—a finding that has been established in the prior literature7,28,29. This lack of significance is likely due to inconsistencies and missing values in the raw data, which obscured true association pattern.

a The association between lung cancer screening eligibility by *USPSTF (based on smoking and age) and the risk of developing second primary lung cancer (SPLC) in lung cancer patients. Hazard ratio was evaluated via multivariable competing risk regression by landmarking at the time of diagnosis and k-year after the diagnosis (k = 1-3) among the subset of patients who are alive at each time. b The predictive performance of the Second Primary Lung Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (SPLC-RAT) with smoking history as the key risk factors over landmarks. AUC was measured over landmarks at the time of diagnosis and k-year after the diagnosis (k = 1-3). Each bar indicates a 95% confidence interval. c Evaluation of three SPLC surveillance strategies in identifying high-risk patients for SPLC: (i) SPLC-RAT-based risk ≥5.6%, (ii) USPSTF eligibility (Yes vs No), and (iii) NCCN guideline-based eligibility (Yes vs No). The Y-axis shows the observed cumulative SPLC incidence stratification by each eligibility criterion, with eligibility determined at initial diagnosis using the smoking data available at the given time. d Evaluation of the same three surveillance strategies performed at landmark 2 years (i.e., two years after the initial diagnosis among those who were event free). * We used the 2013 USPSTF lung cancer screening criteria (i.e., ages 55–80, ≥30 pack-years, and ≤15 years since quitting for former smokers) to replicate the findings of prior studies that showed the association between 2013 USPSTF criteria and SPLC risk at the time of the initial diagnosis in lung cancer patients. ** AUC: A higher AUC value indicates better discriminative ability, with 100% representing perfect discrimination and 50% representing no better than random chance.

In addition, we leveraged the curated longitudinal smoking data to evaluate various post-diagnosis surveillance strategies in lung cancer patients (Fig. 5b–d). Our analysis revealed that a published prediction model for SPLC risk (referred to as SPLC-RAT)7,29 - which incorporates smoking history as well as other clinical risk factors (e.g., tumor characteristics, treatment, prior history of other cancer)—shows robust predictive performance across different landmarks after the initial diagnosis (AUC range: 68.9–77.5%) (Fig. 5b). The AUC (area under the curve) represents the model’s ability to distinguish patients who will develop SPLC from those who will not, where higher values indicate better performance and 50% represents random chance. Further, this analysis demonstrated that the risk model-based surveillance strategy using SPLC-RAT (applying a threshold of 10-year risk ≥ 5.6%) for identifying high-risk individuals to be selected for SPLC surveillance shows superior performance compared to the USPSTF criteria8 (which only considers smoking history and age) and the NCCN guidelines (which incorporates clinical factors alone) (Fig. 5c, d). In particular, the patients classified in the “high-risk” group identified by SPLC-RAT ( ≥ 5.6%) at initial diagnosis exhibited a higher observed 10-year SPLC incidence at 4.2%, compared to 1.4% for the “low-risk” group (Fig. 5c). This difference was more pronounced than those identified by the USPSTF or NCCN guidelines (Fig. 5c). Similar trends were noted at 2 years after the initial diagnosis (Fig. 5d), although the magnitude of the difference became smaller as fewer patients remained event-free and in follow-up.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed a framework that leverages LLMs to extract longitudinal smoking history data from clinical notes in EHR and incorporates rule-based smoothing techniques to enhance data quality by resolving conflicts and inconsistencies. This study demonstrated that comprehensive smoking histories can be accurately extracted and externally validated with high accuracy across all smoking variables using LLMs. Application analysis showed that curated longitudinal smoking data using LLMs can be effectively used to evaluate the relative efficiency of SPLC surveillance strategies. In particular, our analysis revealed that a risk model-based surveillance strategy for SPLC, which combines comprehensive smoking history (such as smoking status, cigarettes per day, smoking duration) with clinical factors (such as history of cancer, treatment, and cancer staging), outperforms existing criteria that rely solely on smoking history and age (USPSTF criteria) or clinical factors like treatment history and staging (NCCN guidelines). These analyses demonstrate that incorporating longitudinal smoking data can provide key insights for evaluating the effective long-term surveillance strategies for lung cancer survivors.

Unlike prior NLP work for smoking abstraction15,16,17,18 that has been limited by focusing on data extraction at a single time point30 or note-level extraction14,23,31 or confined to single institutions32, we conducted NLP-guided sampling to extract smoking variables over longitudinal clinical notes from EHRs across academic and community healthcare setting. For model training, we sampled high-yield notes enriched with smoking details (e.g., including pack-years, quit-years, and smoking status within a single note) to maximize the learning signal. For validation, we selected a more diverse range of notes, including notes with minimal/sparse smoking mentions. By leveraging a more holistic approach, we aimed to enhance the accuracy and generalizability of smoking data extraction, ensuring that our findings are applicable across diverse patient populations, clinical settings, and documentation styles. This is important because it is often observed that LLM models’ performance is not transferable to other healthcare systems due to variations in documentation styles, which limits the utility of models trained in one system.

The proposed LLM framework, in conjunction with our rule-based longitudinal smoothing algorithm, facilitated the effective curation of longitudinal smoking data, addressing commonly observed inconsistencies in smoking history data (e.g., instances where never smokers are inaccurately classified as former smokers). Previous efforts to correct inconsistent smoking data observed in EHRs have been documented32,33,34,35; however, many of these approaches focused on record-level corrections through NLP32, i.e., borrowing information from the most recent clinical notes, or they addressed only smoking status classification. While one study was found to employ a longitudinal correction approach33, they assumed that EHR-documented smoking status was accurate, without accounting for potential recording errors or recall bias that are commonly observed in EHR data. At SHC, we found that ~20% of patients exhibited implausible transitions in smoking status in their longitudinal smoking history data. By applying the proposed smoothing method, we were able to minimize these errors, thereby enabling more reliable research related to patients’ smoking history. Compared to raw extracted data, the smoothed data showed improved statistical power and revealed meaningful clinical patterns that were otherwise obscured by extraction inconsistencies. This improvement enabled us to evaluate efficient surveillance strategies for lung cancer survivors, including a comparison of SPLC-RAT strategies with and without smoking variables (data not shown), which demonstrated that incorporating smoking information enhanced discrimination between low- and high-risk patient populations.

The present study offers several significant contributions. First, we demonstrated that generative LLMs can effectively extract comprehensive smoking data from clinical notes with a high overall accuracy ( > 96%), capturing both categorical (smoking status) and quantitative measures (pack-years, duration, and quit years). While BERT models have been widely used for abstracting smoking variables in prior research36,37, in our study, they underperformed compared to generative LLMs (76.9–82.5% accuracy for BlueBERT and ClinicalBERT vs. 96.6–97.5% for Gemini and GPT4). This performance gap can be attributed to several features of BERT models, including their need for large training data for end-to-end fine tuning of these models and restricted context window for processing clinical notes. In contrast, generative LLMs demonstrated improved performance through prompt engineering alone, requiring less model training. This enhancement was also partly due to prompts that break down the extraction of smoking history into step-by-step tasks, along with validation rules to ensure consistency in the information extracted from a single clinical note. Another key strength of our study is the rigorous manual annotation process over a large number of clinical notes (n = 1183) conducted by two independent annotators who reviewed each of the notes, achieving a great inter-annotator agreement of 91.8%. Furthermore, we evaluated multiple generative LLMs to compare their effectiveness, strengthening the robustness of our findings. Lastly, the external validation of the LLM models improved the generalizability of the proposed approaches, allowing for broader applicability.

Despite the above strengths, our study has limitations. First, while we demonstrated success with three generative LLMs (GPT-4, Gemini 1.5 Flash, and Text Bison), we have not yet explored open-source alternatives like Llama and DeepSeek that would allow healthcare systems to maintain full control over sensitive data through local deployment and direct integration with clinical workflows. Second, our development cohort comprised only patients with lung cancer, which may limit generalizability to other clinical populations where smoking data guide risk assessment and care. We chose lung cancer because smoking variables (status, pack-years, quit-years) are typically documented with more details in this population, yielding high-quality labels for model development. While our training dataset consisted exclusively of information-rich notes, we validated the model on a more heterogeneous dataset where 20% of notes contained only basic smoking information and 6% notes from never-smokers. This validation demonstrated the model’s ability to appropriately abstain (report N/A) when smoking information is insufficient or absent. Nonetheless, external validation in non–lung cancer settings (e.g., primary care, cardiology, perioperative) is recommended before broader deployment. Third, our rule-based smoothing method makes simplifying assumptions about smoking documentation: that information recorded repeatedly are more likely to harbor more accurate information, that clinical notes and structured data are equally reliable, and that smoking status does not change between note dates where no smoking data is available. While these assumptions allow systematic handling of inconsistencies, they may oversimplify complex cases where documentation quality varies, or smoking behavior changes go unrecorded. Fourth, our model training used high-yield notes enriched with detailed smoking information, which may have limited the model’s exposure to sparse or ambiguous documentation during development. Nevertheless, error analysis revealed that many training notes still contained ambiguous or contradictory smoking information despite being information-dense. Additionally, external validation using notes with sparse smoking information and poor documentation quality showed that the models may generalize well. Although these limitations exist, this approach provided a robust and interpretable method for curating consistent longitudinal smoking histories from fragmented clinical data, ultimately aiding in the replication of existing findings in the SPLC surveillance literature.

To conclude, the present study demonstrates a new framework utilizing LLMs to extract smoking information from clinical notes across diverse healthcare settings and incorporating rule-based smoothing techniques to enhance post-deployment data quality. Our findings indicate that these LLM-powered extraction methods, combined with longitudinal smoothing algorithms, effectively address documentation inconsistencies and generate accurate smoking histories. These findings demonstrate the potential for LLM-based tools as provider-facing clinical decision support systems integrated directly within EHRs to inform downstream clinical processes, as accurate smoking history will be useful for surveillance strategies for long-term outcomes in lung cancer survivors. Similar to successful EHR-integrated tools like EHR-QC38, smoking history extraction tools could be deployed to automatically populate and validate smoking information during clinical encounters, reducing documentation burden while ensuring more consistent data. Overall, this study highlights the broader clinical utility of integrating LLMs to improve patient care and outcomes in diverse healthcare environments.

Methods

The study cohorts for natural language processing development

The Oncoshare-Lung database was utilized for this study, which includes EHR data from both academic healthcare (Stanford) and community-based healthcare (Sutter Health) data, linked to the state cancer registry39. The Stanford Healthcare (SHC) cohort for LLM development included 376 lung cancer patients with 1,183 clinical notes that contain detailed smoking-related information (Fig. 2, Supplemental Tables 7, 8). The clinical notes consisted mostly of progress notes, consultation reports, history and physical examination (H&P) documents, and other documentation from oncology, pulmonology, radiology, emergency medicine, surgery, and other departments [Supplemental Table 9]. We excluded only protected/confidential documents and research-flagged notes.

Among the 7060 patients diagnosed with lung cancer between 2000 and 2022, we identified 2913 patients who did not have any structured EHR records for smoking status at the time of lung cancer diagnosis; this timing is important for assessing how smoking history influences cancer prognosis in lung cancer patients, as it captures essential baseline patient information that can help predict outcomes. Structured records were obtained from discrete data fields in the Epic electronic health record system’s social history table within Clarity, Epic’s operational reporting database. These structured fields capture smoking information that clinicians enter into standardized social history sections during patient encounters, captured as structured data elements (e.g., dropdown menus, checkboxes, numerical fields) rather than free-text narratives [Supplemental Table 10]. Of the 2913 patients, 1899 had at least one clinical note containing any smoking-related information (i.e., note containing “smok” or “tobacco”), and hence could potentially benefit from LLM for smoking extraction.

To identify a set of clinical notes (along with their corresponding patients) that are enriched with detailed smoking data for LLM modeling, we further screened 1253 lung cancer patients (and their 4593 smoking-related clinical notes from the time of diagnosis and onwards). We queried these notes using 148 smoking-related key phrases corresponding to the following variables: smoking status (57 keywords, including keywords for never smokers), duration (9 keywords), cessation (17 keywords), intensity (71 keywords), and pack-years (6 keywords). To construct a high-information training set, we conducted an enrichment analysis to evaluate the co-occurrence of smoking-related variables within the clinical notes (Supplemental Table 8). Among the 4593 clinical notes screened, enrichment analysis identified 2668 notes (58%) as high-yield, containing information on smoking status, duration, and cessation. Within this subset, approximately 30% of the notes also included details on smoking intensity, and 20% mentioned pack-years. From these 2668 notes, a random sample of 1183 notes was selected for manual annotation to support LLM model development (Fig. 2).

The external validation cohort comprised 142 lung cancer patients with 500 clinical notes from Sutter Health, a 22-hospital community healthcare system in Northern California. These patients and notes were selected as follows: from 142 lung cancer patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2024 at Sutter Health, we identified 500 clinical notes containing basic smoking keywords (e.g., “smok” or “tobacco”). Using a similar approach as Stanford Health Care, we searched these notes for 148 smoking-related phrases (Supplemental Table 7) and applied stratified sampling as follows: 50% of notes contained keywords for smoking status, pack-years, and duration; 30% included these keywords plus cessation-related keywords; and 20% contained only basic smoking terms (“smok” or “tobacco”). The single Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for both study sites was granted (IRB#: 70545). Waiver of informed consent was granted because this study used retrospective, secondary EHR data, and the research posed no more than minimal risk to participants.

Manual annotation

Two annotators (RK and GN) reviewed and labeled 100 notes together to create an annotation guideline and align their interpretation (Supplemental Table 11), then independently labeled the remaining 1083 notes for 7 smoking variables (smoking status, pack-years, smoking duration, stop smoking age, year of cessation, year since cessation, and pack per day). Inter-annotator agreement was high (ICC = 0.918) (Supplemental Fig. 2). For discrepant cases, a third annotator (IL) provided the final review, and the consensus answer agreed upon by all three annotators was considered the ground truth label for model training and evaluation.

BERT-based smoking status classification

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is a deep learning language model that encodes text by applying attention mechanisms to capture bidirectional relationships between words in a sequence. For this analysis, we utilized two domain-adapted BERT variants: BlueBERT, which was pre-trained on 4.5 billion words from PubMed abstracts and clinical notes from MIMIC-III, and ClinicalBERT, which was specifically pre-trained on clinical notes from the MIMIC-III database. We implemented a two-stage classification pipeline to determine smoking status from clinical notes. For each clinical note, we identified all occurrences of smoking-related keywords, extracted a window of 100 characters before and after each keyword (including the keyword itself), and concatenated these windows after removing duplicates to form a condensed input in order to address BERT’s 512-token input limit. Each preprocessed note was passed as input to ClinicalBERT or BlueBERT, which we fine-tuned end-to-end for sequence-level classification. All parameters, including the embeddings, all 12 encoder layers, pooler, and a linear classification head, approximately ~109 M parameters were left trainable and updated by back-propagation from the cross-entropy loss. Models were optimized with AdamW optimizer using a learning rate of 2 × 10⁻⁵, weight decay 0.01. We trained for up to 5 epochs, evaluated each epoch, and loaded the best checkpoint at the end based on validation performance. The dataset was split into 946 training notes and 237 test notes.

Prompt development for generative LLMs

We evaluated three generative LLMs- Gemini 1.5 Flash, GPT-4, and PaLM 2 TextBison - using a zero-shot prompt. Gemini 1.5 Flash (gemini-1.5-flash-001) is a lightweight multimodal model optimized for speed and efficiency through knowledge distillation from Gemini 1.5 Pro. We accessed it through Google Cloud Platform API with temperature set to 0 for deterministic outputs. GPT-4 is OpenAI’s transformer-based language model that uses reinforcement learning from human feedback for alignment. We accessed GPT-4 through Stanford’s SecureGPT platform, a beta implementation designed specifically for secure processing of PHI within Stanford Health Care and Stanford School of Medicine. PaLM 2 Text Bison (text-bison@002) is Google’s language model with enhanced multilingual capabilities, reasoning, and coding performance. We accessed it through GCP API with temperature set to 0. For notes exceeding the 8192-token input limit, we preserved paragraphs containing smoking-related keywords and surrounding context while removing unrelated content.

The prompt was developed through a sequential design process, starting with an initial draft based on annotation guidelines and tested on 100 notes. It was then refined iteratively through repeated error analysis on the development set (847 notes). The final prompt included definitions for each variable, structured output formats, and example phrases based on insights from the error analysis (full prompt available upon request).

Evaluation of comparative performance in BERT & generative LLMs (Note-level Performance)

We evaluated BERT and generative LLMs for smoking status extraction using 237 test notes from SHC and 500 notes from Sutter Health. The goal was to identify a BERT model with performance comparable to generative LLMs for smoking status detection and extend its use to other variables, or to select the best-performing generative LLMs based on accuracy. We evaluated model performance by calculating accuracy for each of the 7 smoking variables. Our evaluation employed an exact match criterion while also accommodating different documentation styles to reflect real-world documentation. When smoking intensity was reported in different units (weekly or monthly), we converted these to pack-per-day before comparison through post-extraction parsing. For ground truth values containing ranges (such as “10–15 years”), we accepted extractions that fell within the range. Additionally, and importantly, cases where both the model extraction and ground truth were missing (e.g., no pack-years mentioned; NA to NA) were counted as exact matches, recognizing that correctly identifying absent information is also clinically valuable.

Deployment of Gemini 1.5 to the LC Cohort (N = 4792) to Curate Longitudinal Smoking data and Rule-based Smoothing Algorithm

To curate comprehensive longitudinal smoking data, the best-performing LLM was deployed on an independent set of 79,408 notes from 4792 lung cancer patients who had baseline smoking data (i.e., within 1 year before or 6 months after initial diagnosis). We combined LLM-extracted variables from these notes with 58,228 structured records containing smoking status, pack-years, and quit dates, creating longitudinal patient smoking history from lung cancer diagnosis onward.

A rule-based smoothing algorithm was developed to resolve temporal inconsistencies in smoking status (e.g., implausible transitions from current to never smoker) that utilized a state transition graph (Fig. 4C) that defined plausible versus implausible smoking status changes and integrated comprehensive information across different smoking variables (e.g., pack-years, quit dates, status) over the full range of longitudinal records within each patient. The algorithm did not distinguish between LLM-extracted and structured data sources. The algorithm operated in two steps. In “Step 1: Record-level correction”, we first address record-level inconsistencies (as opposed to longitudinal inconsistencies) between smoking status and quantitative smoking variables (e.g., a never smoker having a quit date entered). In resolving these inconsistencies, we assign greater weight to the quantitative variables (e.g., changing “Never” to “Former” when a specific quit date is entered), which is based on the premise that errors are more likely to occur in entering smoking status than in recording specific quit dates. For records with “Never” status but non-zero pack-years or pack-days, we corrected to the most recent non-never status from previous records, or the closest from future records if none existed.

In “Step 2: Longitudinal correction”, after resolving the record-level inconsistencies, we proceed to identify longitudinal inconsistencies in smoking status transitions. We utilize a state transition graph (Fig. 4c) to distinguish between plausible and implausible changes in smoking status, while also incorporating additional information from the quantitative smoking variables in previous records to identify most probable sequence of smoking status changes. For example, after examining consecutive records chronologically, when an implausible transition (e.g., a transition from “Former” to “Never”) was found (Supplemental Table 12), we checked for supporting quantitative smoking data in prior records (e.g., pack-years = “15” or quit dates = “2015-12-15”). If such records are found, the algorithm will correct the status from “Never” to “Former”. The rationale behind this approach is that errors are more likely to occur in entering smoking status than in recording quantitative smoking data, and hence we place greater weights on the quantitative variables, as they are generally less prone to error. If no quantitative smoking records are found, we determined that earlier smoking status were erroneous and adjusted them from “Former” to “Never”, indicating insufficient evidence to support the “Former” status. Corrections were applied iteratively from earliest to latest records until no further changes were needed. Some examples of a patient’s smoking history before and after the smoothing algorithm are shown in Supplemental Table 12.

Evaluation of the clinical utility of the curated longitudinal smoking data

We evaluated the clinical utility of the curated longitudinal smoking data in monitoring lung cancer patients after their initial diagnosis. Second primary lung cancer (SPLC) presents a significant risk among lung cancer (LC) survivors, yet no evidence-based guidelines exist for its screening. Choi et al.29 demonstrated an association between the USPSTF-2013 screening criteria (i.e., aged 55–80, smoking pack-years > =30, quit years < =15 years for former smokers) and SPLC risk at the time of initial primary lung cancer (IPLC) diagnosis. However, prior studies relied on static smoking data at IPLC diagnosis and did not evaluate how SPLC eligibility and risk prediction evolve longitudinally, including changes in smoking behaviors. While a risk assessment tool for second primary lung cancer, called SPLC-Risk Assessment Tool (SPLC-RAT) was previously developed and validated using static baseline smoking data from epidemiological cohorts, it has not been tested with longitudinal real-world smoking histories7.

The aims of this application analysis were to: (1) characterize longitudinal smoking data (e.g., duration, pack-years, current smoking status, cigarette per day) and assess the eligibility for USPSTF 2013 criteria following an IPLC diagnosis in a real-world lung cancer cohort derived from EHRs; (2) to evaluate the longitudinal performance of SPLC-RAT, including metrics such as area under the curve (AUC), Brien score, and calibration; and (3) to compare the risk stratification ability of SPLC-RAT-based surveillance with USPSTF8 and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines40.

In the current study, second primary lung cancer (SPLC) was defined using the established Martini and Melamed criteria41. Using the same cohort of 4,792 patients in the previous section, longitudinal smoking data were analyzed at diagnosis and at yearly intervals (k = 0, 1, 2, …, 5 years after the initial diagnosis) among patients who are still event-free (i.e., no death or SPLC) at k years post-diagnosis. The following metrics were also assessed at each given time: (1) the distribution of smoking status, (2) median and IQR of smoking pack-years, and (3) the proportion of the patients who meet the 2013 USPSTF lung cancer screening eligibility (i.e., age 55–80, ≥30 pack-years, current/former smokers who quit within 15 years) which was identified as an independent predictor of SPLC risk29. Furthermore, we evaluated the association between the 2013 USPSTF criteria and SPLC risk at diagnosis and at k years post-diagnosis (where k = 1, 2, 3) using a cause-specific Cox regression that accounted for the competing risk of death. In this analysis, we compared the curated, smoothed longitudinal smoking data with the unsmoothed raw smoking data to assess the impact of smoothing on clinical application.

The performance of SPLC-RAT was evaluated at each time point using time-dependent AUC. The SPLC-RAT tool was proposed to identify high-risk patients for surveillance and requires smoking status, quit duration for former smokers ( ≤ 15 or >15 years), smoking duration, daily cigarette consumption (0–100/day), and clinical factors including histology, stage, surgery, and prior cancer history for comprehensive risk assessment. Patients exceeding the 5.6% 10-year risk threshold (representing the 80th percentile of estimated risk in the epidemiological cohorts) were classified as “high-risk” for surveillance. The AUC measured the model’s ability to distinguish between patients who would later develop SPLC versus those who would not, among patients who were still alive and had not developed SPLC by that time point. A higher AUC value indicates better discriminative ability, with 100% representing perfect discrimination and 50% representing no better than random chance.

We compared SPLC-RAT with USPSTF and NCCN guidelines at diagnosis and 2 years after diagnosis through cumulative incidence analyses to identify optimal strategies for lung cancer patient monitoring. We used the Aalen-Johansen estimator to calculate the cumulative incidence of SPLC while accounting for the competing risk of death. For each guideline, patients were classified as high-risk or low-risk, and separate cumulative incidence curves were generated for each risk group. Greater separation between the high-risk and low-risk curves indicates better risk stratification ability.

The USPSTF criteria classified patients as high-risk if they met the following eligibility requirements: ages 55–80 years, ≥30 pack-years smoking history, and ≤15 years since cessation for former smokers (2013 criteria8), with updated 2021 criteria expanding to ages 50–80 years and ≥20 pack-years9. The NCCN criteria classified patients as high-risk based on clinical characteristics: non-small cell lung cancer patients with stage I-II treated with surgery or radiation, all stage-III patients, stage-IV oligometastatic patients, or all small cell lung cancer patients40. Unlike SPLC-RAT and USPSTF, NCCN criteria do not incorporate dynamic smoking history variables.

Data availability

The data can be accessed for research purposes after Institutional Review Board approval via the Stanford Research Informatics Center.

Code availability

The R code used in this analysis is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Atlanta (GA), (2014).

Siegel, R. L., Kratzer, T. B., Giaquinto, A. N., Sung, H. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 75, 10–45 (2025).

Scala, M. et al. Dose-response relationships between cigarette smoking and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Epidemiol. 33, 640–648 (2023).

Jethwa, A. R. & Khariwala, S. S. Tobacco-related carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 36, 411–423 (2017).

Iodice, S., Gandini, S., Maisonneuve, P. & Lowenfels, A. B. Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 393, 535–545 (2008).

Jacob, L., Freyn, M., Kalder, M., Dinas, K. & Kostev, K. Impact of tobacco smoking on the risk of developing 25 different cancers in the UK: a retrospective study of 422,010 patients followed for up to 30 years. Oncotarget 9, 17420–17429 (2018).

Choi, E. et al. Risk model-based management for second primary lung cancer among lung cancer survivors through a validated risk prediction model. Cancer 130, 770–780 (2024).

Moyer, V. A. & Preventive Services Task Force, U. S. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 160, 330–338 (2014).

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Lung Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 325, 962–970 (2021).

Polubriaginof, F., Salmasian, H., Albert, D. A. & Vawdrey, D. K. Challenges with collecting smoking status in electronic health records. AMIA. Annu. Symp. Proc. 2017, 1392–1400 (2018).

Patel, N. et al. A comparison of smoking history in the electronic health record with self-report. Am. J. Prev. Med. 58, 591–595 (2020).

Cole, A. M., Pflugeisen, B., Schwartz, M. R. & Miller, S. C. Cross sectional study to assess the accuracy of electronic health record data to identify patients in need of lung cancer screening. BMC Res. Notes 11, 14 (2018).

Wang, L., Ruan, X., Yang, P. & Liu, H. Comparison of three information sources for smoking information in electronic health records. Cancer Inf. 15, 237–242 (2016).

Yang, X. et al. A natural language processing tool to extract quantitative smoking status from clinical narratives. in 2020 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI) 1–2 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICHI48887.2020.9374369 (2020).

Bazoge, A., Morin, E., Daille, B. & Gourraud, P.-A. Applying natural language processing to textual data from clinical data warehouses: systematic review. JMIR Med. Inform. 11, e42477 (2023).

Ruckdeschel, J. C. et al. Unstructured data are superior to structured data for eliciting quantitative smoking history from the electronic health record. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. e2200155 https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.22.00155 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. A study of social and behavioral determinants of health in lung cancer patients using transformers-based natural language processing models. Amia. Annu. Symp. Proc. 2021, 1225–1233 (2022).

Bae, Y. S. et al. Keyword extraction algorithm for classifying smoking status from unstructured bilingual electronic health records based on natural language processing. Appl. Sci. 11, 8812 (2021).

Xue, Y. et al. SmokeBERT: a BERT-based model for quantitative smoking history extraction from clinical narratives to improve lung cancer screening. medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.06.18.25329870 (2025).

Shah-Mohammadi, F. & Finkelstein, J. Extraction of substance use information from clinical notes: generative pretrained transformer–based investigation. JMIR Med. Inform. 12, e56243 (2024).

Bhagat, N., Mackey, O. & Wilcox, A. Large language models for efficient medical information extraction. AMIA Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2024, 509–514 (2024).

Chen, D., Alnassar, S. A., Avison, K. E., Huang, R. S. & Raman, S. Large language model applications for health information extraction in oncology: scoping review. JMIR Cancer 11, e65984 (2025).

Wu, J. et al. Hazard-aware adaptations bridge the generalization gap in large language models: a nationwide study. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.14.25322312 (2025).

LeLaurin, J. H. et al. Concordance between electronic health record and tumor registry documentation of smoking status among patients with cancer. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 518–526 https://doi.org/10.1200/CCI.20.00187 (2021).

Krebs, P. et al. Utility of using cancer registry data to identify patients for tobacco treatment trials. J. Regist. Manag. 46, 30–36 (2019).

Farquhar, S., Kossen, J., Kuhn, L. & Gal, Y. Detecting hallucinations in large language models using semantic entropy. Nature 630, 625–630 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Medical Hallucination in Foundation Models and Their Impact on Healthcare. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.02.28.25323115 (2025).

Aredo, J. V. et al. Tobacco smoking and risk of second primary lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. Publ. Int. Assoc. Study Lung Cancer 16, 968–979 (2021).

Choi, E. et al. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for second primary lung cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 114, 87–96 (2021).

Bazoge, A., Morin, E., Daille, B. & Gourraud, P. A. Applying Natural Language Processing to Textual Data From Clinical Data Warehouses: Systematic Review. JMIR Med Inform 11, e42477 (2023).

Palmer, E. L., Hassanpour, S., Higgins, J., Doherty, J. A. & Onega, T. Building a tobacco user registry by extracting multiple smoking behaviors from clinical notes. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 19, 141 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Leveraging natural language processing to identify eligible lung cancer screening patients with the electronic health record. Int. J. Med. Inf. 177, 105136 (2023).

Kukhareva, P. V. et al. Inaccuracies in electronic health records smoking data and a potential approach to address resulting underestimation in determining lung cancer screening eligibility. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 29, 779–788 (2022).

Martin, P. M. Can we trust electronic health records? The smoking test for commission errors. BMJ Health Care Inform. 25, 105–108 (2018).

Garies, S. et al. Methods to improve the quality of smoking records in a primary care EMR database: exploring multiple imputation and pattern-matching algorithms. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 20, 56 (2020).

Ebrahimi, A. et al. Identification of patients’ smoking status using an explainable AI approach: a Danish electronic health records case study. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 24, 114 (2024).

Turchin, A., Masharsky, S. & Zitnik, M. Comparison of BERT implementations for natural language processing of narrative medical documents. Inform. Med. Unlocked 36, 101139 (2023).

Ramakrishnaiah, Y., Macesic, N., Webb, G. I., Peleg, A. Y. & Tyagi, S. EHR-QC: A streamlined pipeline for automated electronic health records standardisation and preprocessing to predict clinical outcomes. J. Biomed. Inform. 147, 104509 (2023).

Su, C. et al. Oncoshare-lung: novel three-way linkage of neighboring academic and community medical centers to state cancer registry for lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 43, e23292–e23292 (2025).

Network, NationalComprehensiveCancer Treatment by Cancer Type, Accessed March 1, 2022.

Martini, N. & Melamed, M. R. Multiple primary lung cancers. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 70, 606–612 (1975).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute’s grant (5R01CA282793) and by the Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) of the National Cancer Institute under Award Number P30CA124435. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research used data or services provided by STARR, “STAnford medicine Research data Repository”, a clinical data warehouse containing live Epic data from Stanford Health Care, the Stanford Children’s Hospital, the University Healthcare Alliance and Packard Children's Health Alliance clinics and other auxiliary data from Hospital applications such as radiology PACS. STARR platform is developed and operated by Stanford Medicine Research Technology team and is made possible by funding from Stanford School of Medicine Dean's Office.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, I., Graber-Naidich, A., Zhang, M. et al. Leveraging large language models to extract smoking history from clinical notes for lung cancer surveillance. npj Digit. Med. 8, 731 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02009-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02009-y