Introduction

Political participation has been a subject of scholarly enquiry for decades, with researchers calling for increased attention to the personality traits of those who engage in political activities (Levinson, 1958; Vecchione and Caprara, 2009). Understanding these traits helps comprehend the characteristics of individuals involved in democratic processes and assess the quality of such participation (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Rogoza et al., 2022). While the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and political participation has been extensively explored (e.g., Schoen and Schumann, 2007; Vecchione and Caprara, 2009), there has been less attention on the contribution of darker aspects of personality (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Fazekas and Hatemi, 2020; Peterson and Palmer, 2021).

Dark personality traits, such as Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (the constellation of the three called Dark Triad), have been linked to morally questionable and socially undesirable behaviours, including coercion, manipulation, aggression, and avoidant attachment patterns (Blais and Pruysers, 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Peterson and Palmer, 2019; Rogoza et al., 2022). Despite their distinct characteristics, these traits share common tendencies like self-promotion, emotional coldness, duplicity, and aggressiveness (Paulhus and Williams, 2002). Recent studies indicate that narcissism and psychopathy, but not machiavellianism, significantly influence political participation (Chen et al., 2020; Rogoza et al., 2022). Some researchers suggest that psychopathy encompasses elements of Machiavellianism, proposing the concept of “Dark Dyad” only focusing on psychopathy and narcissism (Rogoza and Cieciuch, 2017; 2018).

Research on dark personality traits and political behaviours reveals that individuals with such characteristics often seek power, dominance, and authority, engaging in political activities to fulfil personal goals (Blais and Pruysers, 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Peterson and Palmer, 2019; Rogoza et al., 2022). However, existing literature predominantly examines offline political engagement and mainly focuses on Western contexts, overlooking cross-cultural perspectives and digital forms of political engagement (e.g., Chen et al., 2020; Fazekas and Hatemi, 2020; Peterson and Palmer, 2021; Rogoza et al., 2022). The rise of digital media has made online political participation a convenient and increasingly preferred form of engagement (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2011; Yang and DeHart, 2016). Thus, to address these gaps, we advocate focusing on online political engagement, especially comparing Western and non-Western settings.

Additionally, we believe it is crucial to examine the impact of narcissism and psychopathy on political participation alongside other socio-psychological and cognitive factors closely associated with engagement in online activities. Therefore, this study also integrates the concept of FoMO (fear of missing out) as a significant socio-psychological trait and cognitive ability, as a general intelligence indicator, in relation to online political participation. The former has been conceptually linked to boredom proneness, a trait associated with sensation-seeking and impulsivity (Çelik et al., 2022; Przybylski et al., 2013) and related to online behaviours. The latter refers to critical thinking and reasoning linked to political engagement (Morton et al., 2011; Ståhl and van Prooijen, 2018). Particularly, cognitive ability may play a moderating role in influencing how individuals process political information and regulate impulsive engagement (Pennycook and Rand, 2019). There has been limited empirical research on how cognitive ability moderates the effects of dark personality traits and socio-psychological factors on online political participation. By incorporating these conceptual links, we reinforce different pathways through which dark personality traits, FoMO, and cognitive ability interact to influence online political participation.

Using cross-national survey data from eight countries—China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, the United States, and Vietnam—this study examines the relationships between psychopathy, narcissism, FoMO, cognitive ability, and online political participation across diverse social and political contexts. By analysing these dynamics across different socio-political environments, this study provides deeper insights into how dark personality traits influence online political participation and the complementary role of FoMO and cognitive ability.

The selection of psychopathy, narcissism, FoMO, and cognitive ability is guided by theoretical relevance and empirical evidence. First, the two dark personality traits are key predictors of digital engagement and online political behaviour (Buckels et al., 2014). Among the Dark Triad, we focus on psychopathy and narcissism, as they are most strongly linked to impulsivity, emotional reactivity, and attention-seeking, all of which drive social media-based engagement (Buckels et al., 2014). Second, FoMO explains why individuals engage with political content online, as it reflects an anxiety-driven need to stay connected and participate in discussions (Przybylski et al., 2013). Unlike social media addiction or general anxiety, FoMO is uniquely tied to real-time digital participation. Finally, cognitive ability is included as a predictor and moderator because it influences information processing, engagement styles, and interactions with dark personality traits (Stanovich and West, 2008; Pennycook and Rand, 2019). Unlike education or media literacy, cognitive ability can fundamentally explain individual differences in political behaviour. By integrating these constructs, our study offers a cohesive framework that captures the psychological mechanisms driving online political participation.

Literature review

Narcissism, psychopathy, and online political participation

Several studies have established a connection between dark personality traits and pursuing power, social dominance, and authority (Paulhus and Williams, 2002; Rogoza et al., 2022; Rogoza and Cieciuch, 2018). Specifically, narcissism involves the pursuit of gratification through vanity or egotistic admiration of one’s attributes (Sheldon et al., 2019). This trait is central to self-perceived leadership abilities, maladaptive self-absorption tendencies, and manipulative behaviours (Rogoza and Cieciuch, 2018). Narcissism is marked by grandiosity—a sense of self-importance—alongside a desire for admiration, a sense of entitlement, and exploitation of others (Brown et al., 2009). Conversely, psychopathy, deemed the ‘darkest’ of the traits, is associated with disruptive behaviours, such as bullying and antisocial conduct (Rogoza and Cieciuch, 2018). Characterised by manipulativeness, superficial charm, egocentricity, exploitation, dishonesty, and irresponsibility, psychopathy is considered an extreme version of common personality aspects (Cleckley, 1988). Despite their distinctions, narcissism and psychopathy share socially offensive characteristics that can influence political participation.

The relationship between dark personality traits and political participation is complex. Politics often involves conflict, rivalry, and public attention—elements that may repel some but attract individuals with dark personalities (Peterson and Palmer, 2021). Narcissists, for instance, may engage in politics to boost their self-esteem (Rogoza et al., 2022). They thrive on being in the public eye, seek constant self-improvement, and crave admiration (Morf and Rhodewalt, 2001). Their extroverted and socially active nature leads them to participate in politics to fulfil social needs like self-enhancement (Raskin and Hall, 1979). Political involvement allows narcissists to inflate their egos (Rogoza et al., 2022). Both narcissism and psychopathy are linked to a greater interest in politics (Blais and Pruysers, 2017; Chen et al., 2020), a key predictor of political participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012). Psychopaths, with their manipulative and fearless personalities, may be drawn to the competitive political arena (Chen et al., 2020). Their tendency for social dominance may encourage political engagement by minimising perceived threats and risks from such behaviours (Lilienfeld et al., 2014).

However, the correlation between psychopathy and political participation is debated. Some argue that psychopaths’ antisocial nature should reduce their participation in politics due to their disregard for laws, social norms, and reputation (Rogoza et al., 2022). Nonetheless, others suggest that psychopaths might engage in politics to fulfil non-normative desires (Chen et al., 2020). Narcissists and psychopaths might also view political participation as a means to exert influence in political systems and society (Chen et al., 2020). For instance, narcissists’ extroversion and need for admiration make them more likely to participate in political activities that enhance their self-image (Rogoza et al., 2022). Psychopaths might engage in political behaviours to disrupt political situations (Hare, 1985).

While empirical studies on dark personality traits have primarily focused on offline political participation (e.g., Chen et al., 2020), the association between these traits and participatory behaviours is also expected to extend to digital forms of political activities. Therefore, we state our first set of confirmatory hypotheses below:

H1: Narcissism (H1a) and psychopathy (H1b) are positively associated with online political participation.

Fear of missing out and online political participation

In addition to dark personality traits, this study integrates FoMO as a socio-psychological trait closely correlated with online engagement (Çelik et al., 2022; Fioravanti et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013), facilitating online political participation. FoMO is defined as “a pervasive apprehension that others might be having rewarding experiences from which one is absent” and “the desire to stay continually connected with what others are doing” (Przybylski et al., 2013, p.1841). The concept has gained prominence with the substantial rise of social media use, as these platforms provide real-time information about various social and political activities in which individuals may want to participate in satisfying their social and psychological needs (e.g., Alt, 2015; Przybylski et al., 2013).

Studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of FoMO engage more significantly with social networking sites (Fioravanti et al., 2021; Przybylski et al., 2013). This greater engagement can be explained by the self-determination theory, which posits that competence, autonomy, and relatedness are three fundamental socio-psychological needs essential for fostering health and well-being (Deci and Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2000). Individuals experience FoMO to meet these needs, resulting in increased engagement in online activities (Çelik et al., 2022). Research indicates that individuals with lower satisfaction levels in these areas tend to have higher levels of FoMO, leading to more frequent social media use and engagement in online activities (Przybylski et al., 2013).

Research on FoMO is relatively underexplored in relation to political engagement. Some studies have identified a link between FoMO and online activities, such as social media usage, but the direct connection between FoMO and online political involvement is less understood. Building on existing literature, we propose that FoMO is likely correlated with online political participation as engaging in politics online is a social experience, and individuals with heightened FoMO may participate to avoid missing out on this aspect of public discourse. Thus, those with stronger FoMO may exhibit greater involvement in online political activities to fulfil their socio-psychological needs, including a sense of belonging (Seidman, 2013) and avoiding boredom (Lampe et al., 2007). Furthermore, individuals with heightened FoMO actively monitor social events and information, leading to greater exposure to news content, which can foster political engagement. Based on this discussion, we propose the following hypothesis: FoMO is positively correlated with online political participation.

H2: FoMO is positively associated with online political participation.

The conditional role of cognitive ability

In addition to the direct relationships between the two dark personality traits, FoMO, and online political participation, this study examines whether individuals’ cognitive ability influences these relationships. Cognitive ability reflects an individual’s capacity to understand complex concepts and think critically (Morton et al., 2011; Ståhl and van Prooijen, 2018). This capacity includes intuitive problem-solving and an analytical cognitive style (Pennycook et al., 2012). Individuals with higher abilities are better at processing information, making controlled decisions, and engaging in motivated reasoning (Lodge and Hamill, 1986). They also possess better social skills and an understanding of social situations (Pauls and Crost, 2005). In essence, cognitive ability aids in processing complex situations and novel information.

Given that those with higher cognitive ability can process information efficiently (Lodge and Hamill, 1986), they are likely better equipped to weigh the risks and benefits associated with political participation, leading to more informed decisions. However, without supporting these assumptions, we propose a research question instead of a hypothesis.

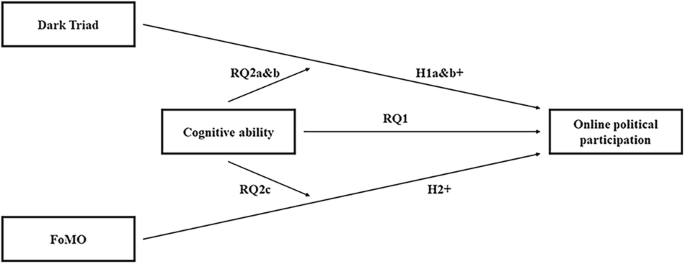

RQ1: How is cognitive ability associated with online political participation?

While existing research suggests that dark personalities and FoMO are associated with online political engagement, the impact of cognitive ability on these relationships remains unexplored. Investigating this could offer novel insights into how personality, social psychology, and cognition relate to online political activities. Given that cognitive ability may influence individuals’ risk assessment and decision-making, the strength of the relationships between dark personality traits, FoMO, and online political participation will likely vary based on cognitive levels. Thus, we explore whether cognitive capacity moderates the relationship between dark personality traits, FoMO, and online political engagement. Consequently, owing to the uncertain conditional impact of cognitive ability, we propose the following research question instead of positing a hypothesis:

RQ2: How does cognitive ability influence the positive relationship between narcissism (RQ2a), psychopathy (RQ2b), FoMO (RQ2c), and online political participation?

The conceptual framework of the study is presented in Fig. 1.

Methods

Participants

We conducted a cross-national survey in June 2022, collecting data from eight countries (total sample size N = 8070, final response rate = 76%), namely the United States (n = 1010), China (n = 1010), Singapore (n = 1008), Indonesia (n = 1010), Malaysia (n = 1002), the Philippines (n = 1010), Thailand (n = 1010) and Vietnam (n = 1010) = 1010). The survey was conducted by Qualtrics LLC, a well-known research firm often used by social scientists. For survey questions, English was used in the United States and Singapore, and regional languages were used in other countries. We used quota sampling techniques to match the survey sample to the population (age and sex quotas) to increase the representativeness of the survey study findings. All participants of the study provided informed consent before participation. The review board at Nanyang Technological University approved the study.

Measures

All measures use previously validated scales.

Online political participation

We asked respondents in each country on a 5-point scale (1 = never to 5 = always) in the past year how often they have engaged in the six online political activities (e.g., Ahmed and Lee, 2023). The scale was created by averaging the responses to the six items. See Appendix A for details.

Psychopathy and narcissism

We measured two dark triad domains, i.e., psychopathy and narcissism, on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) using short dark triad items (Jonason and Webster, 2010). The scales were created by averaging the responses to the four items. See Appendix A for details.

FoMO

It was gauged by asking respondents the following on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) (Alt, 2015; Przybylski et al., 2013). Below is a collection of statements about your everyday experience. Using the scale provided, please indicate how true each statement is of your general experiences. Please answer according to what really reflects your experiences rather than what you think your experiences should be.” Sample items are: “I fear others have more rewarding experiences than me” and “I get worried when I find out my friends are having fun without me”. The scale was created by averaging the responses to ten items.

Cognitive ability

It was measured using the Wordsum test. The test closely resembles general intelligence and is often used to assess cognitive skills and analytical thinking (Ganzach et al., 2018). The correct answers to the ten questions were combined to create an index.

We controlled for demographic variables, including age, gender, education, and income. In addition, we controlled other motivational covariates, including political interest, social media news use, and traditional media news use, which are known to have a significant association with online political participation (Gil de Zúñiga et al., 2012; Valenzuela et al., 2011; Yang and DeHart, 2016). Descriptive statistics for all variables in this study are included in Appendix B, and reliability details for critical variables are included in Appendix C. Except for cognitive ability in Indonesia, all key variables achieved satisfactory reliability.

Results

Table 1 presents zero-order correlations between the key variables of the study. We broadly observe that the dark traits and FoMO are positively associated with political engagement across countries. A negative association between cognitive ability and dark personality traits is also observed.

The results presented in Table 2 suggest that narcissism is only positively associated with online political participation in the United States (β = 0.058, p < 0.05), the Philippines (β = 0.076, p < 0.01), and Thailand (β = 0.059, p < 0.05). We find that psychopathy is positively associated with online political participation across all contexts: the United States (β = 0.142, p < 0.001), China (β = 0.139, p < 0.001), Singapore (β = 0.165, p < 0.001), Indonesia (β = 0.116, p < 0.001), Malaysia (β = 0.201, p < 0.001), Philippines (β = 0.100, p < 0.001), Thailand (β = 0.194, p < 0.001), and Vietnam (β = 0.183, p < 0.001).

Similarly, FoMO is found to be positively associated with online political participation in all countries: the United States (β = 0.390, p < 0.001), China (β = 0.324, p < 0.001), Singapore (β = 0.362, p < 0.001), Indonesia (β = 0.340, p < 0.001), Malaysia (β = 0.375, p < 0.001), the Philippines (β = 0.299, p < 0.001), Thailand (β = 0.357, p < 0.001), and Vietnam (β = 0.505, p < 0.001).

Moreover, we find that cognitive ability is negatively associated with online political participation across all contexts: the United States (β = −0.089, p < 0.001), China (β = −0.092, p < 0.001), Singapore (β = −0.180, p < 0.001), Malaysia (β = −0.180, p < 0.001), the Philippines (β = −0.071, p < 0.01), Thailand (β = −0.072, p < 0.01), and Vietnam (β = −0.085, p < 0.001).

Besides, we find that those with higher political interest and frequent traditional news media use are more likely to engage in online political participation across all contexts (for all coefficients, see Table 2).

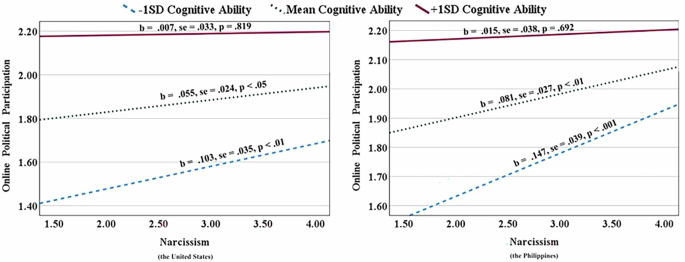

Next, we examined the moderation relationships. First, we find that the interaction effect of narcissism and cognitive ability on online political participation is only significant for the United States (β = −0.144, p < 0.05) and the Philippines (β = −0.272, p < 0.05). The results are illustrated in Fig. 2. It suggests that the positive relationship between narcissism and online political participation is more substantial for individuals with low cognitive ability, followed by average cognitive ability. However, the relationship is insignificant for individuals with high cognitive ability (see Fig. 2 for all slope values).

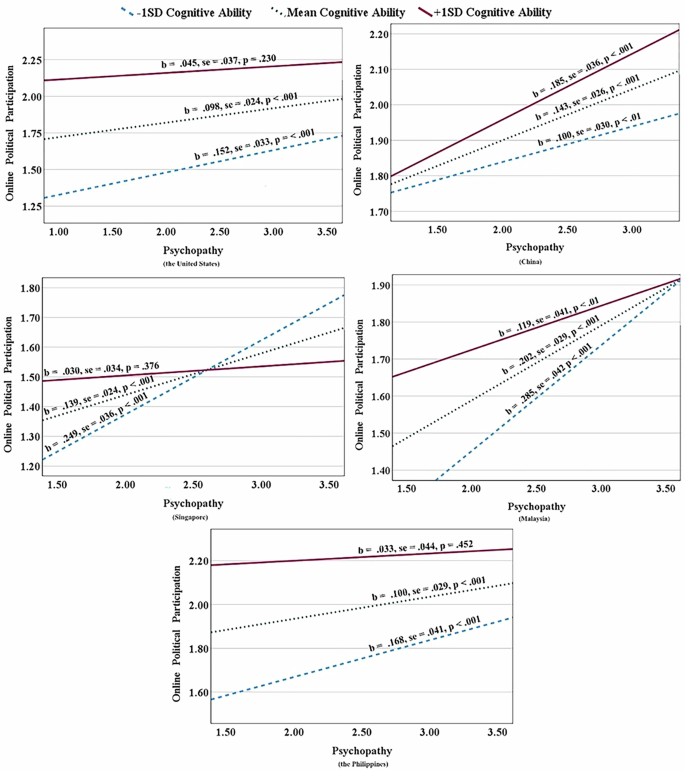

Then, we find that the interaction effect of psychopathy and cognitive ability on online political participation is significant for the United States (β = −0.139, p < 0.05), China (β = 0.182, p < 0.05), Singapore (β = −0.392, p < 0.001), Malaysia (β = −0.290, p < 0.01) and the Philippines (β = −0.235, p < 0.05). These relationships are illustrated in Fig. 3.

More specifically, we observe that for Malaysia, the positive relationship between psychopathy and online political participation is stronger for low cognitive ability individuals, followed by average and high cognitive ability individuals, respectively.

For the United States, Singapore, and the Philippines, the positive relationship between psychopathy and online political participation is more substantial for low cognitive ability individuals, followed by average cognitive ability individuals. Still, the relationship is insignificant for individuals with high cognitive ability.

However, contrary to the overall trend in other countries, for China, the positive relationship between psychopathy and online political participation is stronger for high cognitive ability individuals, followed by average and low cognitive ability individuals, respectively (see Fig. 3 for all slope values).

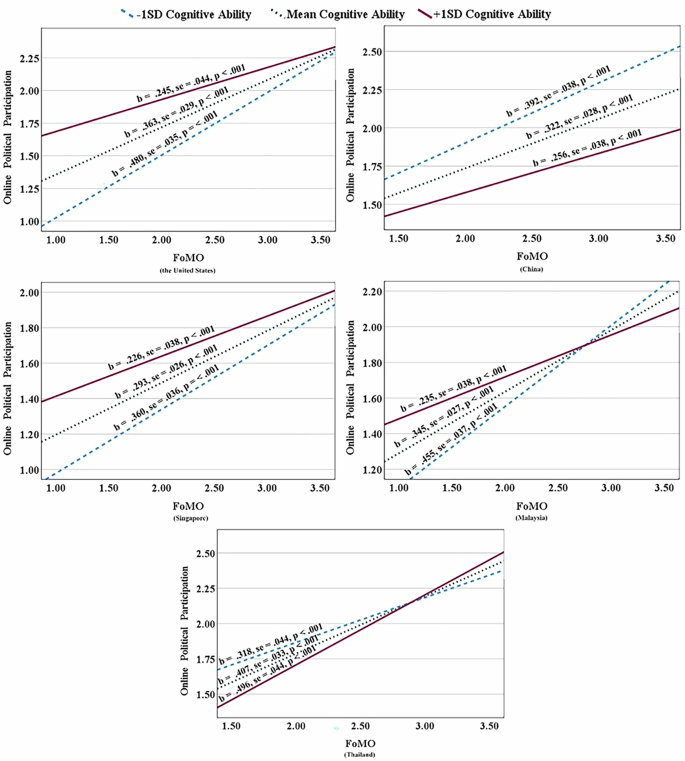

Finally, we find that the interaction effect of FoMO and cognitive ability on online political participation is significant for the United States (β = −0.266, p < 0.001), China (β = −0.328, p < 0.01), Singapore (β = −0.209, p < 0.05), Malaysia (β = −0.369, p < 0.001), and Thailand (β = 0.349, p < 0.01). These relationships are illustrated in Fig. 4.

For the United States, China, Singapore, and Malaysia, the positive relationship between FoMO and online political participation is stronger for low cognitive ability individuals, followed by average and high cognitive ability individuals, respectively.

However, for Thailand, the positive relationship between FoMO and online political participation is interestingly stronger for high cognitive ability individuals, followed by average and low cognitive ability individuals, respectively (see Fig. 4 for all slope values).

Discussion

To develop a cohesive theoretical model explaining online political participation, we integrate two dark personality traits (psychopathy and narcissism), fear of missing out (FoMO), and cognitive ability into our framework, each with distinct yet interrelated psychological mechanisms that shape individuals’ engagement in digital political behaviours.

Building upon existing understanding of the influence of dark personality traits on offline political engagement, this cross-national investigation expands its scope to the online domain. The findings reveal a significant association between psychopathy and online political engagement across all studied contexts. This suggests that heightened psychopathic tendencies are positively linked to increased frequency of online political participation, a relationship that remains consistent despite variances in cultural and political landscapes. Narcissism was also significantly associated with online political participation, but only in the United States, the Philippines, and Thailand.

This indicates that while psychopathy consistently forecasts online political engagement across diverse cultural and political contexts, narcissism does not exhibit the same predictive power. However, the overarching association between the two dark personality traits and online political engagement unveils insights into the nature of participation in the studied contexts and the characteristics of individuals within an internet-mediated participatory civic culture. It presents a significant concern, as the involvement of individuals with psychopathic and narcissistic traits in online political endeavours could precipitate profound social, political, and institutional shifts that may not align with the broader public interest or societal well-being but rather cater solely to the gains of these individuals. In societies marked by active online political engagement, this raises concerns regarding the representation of those involved in political affairs, particularly concerning the character of influential participants shaping political systems and processes. In other words, it prompts reflection on the quality of participation facilitated by such personalities and their impact on the overall democratic culture. While our study does not delve into the subtleties of online political participation, recent research indicates individuals exhibiting dark personalities are more likely to fuel uncivil online interactions and are prone to disseminating misinformation across digital platforms (Ahmed and Rasul, 2023; Morosoli et al., 2022; Sternisko et al., 2021). Further investigation is warranted to understand the effects of dark personality traits in online political participation, focusing on scrutinising the nature of online participation and the dynamics of online political discourse.

Furthermore, our findings indicate a strong link between FoMO and participation in online political activities across all contexts. This finding implies that FoMO might play a pivotal role in motivating political engagement online, especially among the youth, who are often seen as disengaged politically yet exhibit high FoMO levels. Such a mechanism could democratise political engagement, broadening its appeal and lowering the entry barriers that typically require a foundational interest or understanding of political matters. Nonetheless, this dynamic poses challenges, including concerns about the quality of participation driven by FoMO. When political participation stems from a fear of exclusion rather than an interest or knowledge of political issues, it risks diluting the depth and efficacy of public engagement in political affairs. Additionally, if anxiety, rather than thoughtful consideration, fuels political participation, it opens opportunities for external manipulation of political views among these individuals. Hence, examining the long-term consequences of FoMO on political participation is crucial for evaluating its effect.

Further, we find that higher cognitive ability was consistently against online political participation and, importantly, moderates the effect of dark personality traits and FoMO in most contexts. The moderation effects are more consistent for psychopathy and FoMO than for narcissism. When examining these interactions across different countries, it becomes evident that the interplay between dark personality traits, FoMO, and online political participation significantly affects individuals with low to average cognitive abilities more than those with high abilities. This nuanced interplay can be explained through several theoretical explanations.

First, individuals with high cognitive ability are more skilled in critical and analytical thinking (Ståhl and van Prooijen, 2018). Therefore, they may be more successful in critically evaluating the political information they are exposed to and less likely to be persuaded by emotional or impulsive inclinations associated with dark personality traits or FoMO. Carefully assessing the available information would allow these individuals to engage in participatory activities driven by informed reasoning rather than personality or socially driven impulsivity. Second, those with high cognitive ability may be more discerning in their information consumption, preferring content that aligns with rational and logical principles over emotionally charged information. This selective exposure may limit the impact of dark personality traits or FoMO on their engagement in online political activities. Third, given that high cognitive individuals have an increased understanding of situations (Stanovich and West, 2000) and engage in elaborative information search processes during decision-making (Cokely and Kelley, 2009), they may be better at mitigating the influence of their dark personality traits or levels of FoMO. Furthermore, their adeptness at foreseeing the consequences of their actions promotes more measured and thoughtful online political participation.

We highlight the importance of considering a holistic view that integrates personality, socio-psychological, and cognitive dimensions to better understand the factors driving political participation. However, these results serve as a reminder that the effects of dark personality traits (e.g., psychopathy or narcissism) or socio-psychological traits (e.g., FoMO) on political behaviour cannot be generalised, especially in the context of online participation, where the costs of engagement are relatively low. It suggests that scholars need to consider cognitive factors when investigating the personality or psychological underpinnings of political behaviour.

Notably, our findings indicate that narcissism was not a significant predictor of online political participation in societies characterised by Confucian cultural values, such as China, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam. This aligns with collectivist cultural frameworks, where self-enhancement tendencies are less socially rewarded (Foster et al., 2003; Hofstede, 2001). In collectivist cultures, social harmony and group cohesion are prioritised, which may reduce the motivation for self-focused political engagement (Markus and Kitayama, 1991). In contrast, in Confucian environments, narcissistic tendencies may not translate as strongly into political engagement due to social norms discouraging overt self-enhancement and limiting political discourse. Moreover, direct effects are consistent across all countries for psychopathy and FoMO emerging as strong predictors of online political participation. Similarly, cognitive ability consistently exhibited a negative association with participation. Whereas interaction effects are more context-dependent, such that psychopathy’s impact on participation was stronger among those with lower cognitive ability in five countries. It suggests that while certain psychological mechanisms hold across cultures, the strength and nature of these relationships are shaped by socio-political and institutional contexts.

The findings of this study also provide valuable insights for policymakers focused on enhancing democratic engagement in online spaces. The strong association between psychopathy, FoMO, and online political participation suggests that emotion and social-driven political participation may be motivated more by sensation-seeking and impulsivity rather than deliberative civic engagement. This highlights the need for platform features and interventions that encourage constructive discourse while mitigating reactive or aggressive political interactions. Additionally, the negative association between cognitive ability and political participation suggests that simplified, accessible political information and digital engagement tools may help bridge cognitive barriers to meaningful participation. Furthermore, the cross-cultural variations observed in our study emphasise the importance of context-specific strategies. For example, what works in individualistic societies, where political expression is encouraged, may not be effective in collectivist or highly regulated societies, where different social norms shape participation. By addressing these dynamics, digital platforms and policymakers can create more inclusive and balanced online political environments, fostering engagement that is constructive.

Finally, the additional bivariate correlation results provide key insights into the relationships between the predictor variables. We find that psychopathy, narcissism, and FoMO are positively correlated across all contexts, suggesting that individuals with higher dark personality traits are also more prone to experiencing FoMO. This finding also suggests that FoMO could be an underlying psychological mechanism linking both psychopathy and narcissism to online political participation. Moreover, the correlations between dark personality traits and cognitive ability provide further implications for understanding personality-driven political behaviours in digital spaces. Our findings reveal more consistent negative associations between psychopathy and cognitive ability (as compared to narcissism), aligning with prior research suggesting that lower cognitive ability may be linked to impulsivity and risk-taking tendencies (Paulhus and Williams, 2002; O’Boyle et al., 2012). This pattern supports our moderation findings, where the impact of psychopathy on online political participation is more pronounced among individuals with lower cognitive ability. These relationships highlight the necessity of considering individual differences in cognitive capacity when examining how dark personality traits drive political engagement. While our primary focus is on the predictors of online political participation, these correlation results offer broader implications for understanding dark personality traits in digital political behaviours.

Limitations and future directions

This study provides valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying online political participation, but several limitations should be acknowledged to contextualise our findings and guide future research. First, psychopathy and narcissism are multidimensional, yet our study examines them broadly. Future research should explore specific subdimensions (e.g., primary vs. secondary psychopathy, grandiose vs. vulnerable narcissism) as they may relate differently to kinds of political engagement (Miller et al., 2017; Pincus and Roche, 2011). Second, our measure of cognitive ability is limited, assessing general ability rather than a complete intelligence profile. Future studies should incorporate performance-based cognitive assessments to better capture cognitive influences on digital political participation (Stanovich and West, 2008). Third, self-reported measures introduce potential biases, such as social desirability and response distortions (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Future research should integrate behavioural or experimental methods to enhance validity. Fourth, our cross-national study spans eight countries, but institutional, cultural, and regulatory factors shape digital political behaviour differently (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Future research should examine how media environments and political systems influence these relationships. Finally, future research should explore the tested relationships further using mediation models with longitudinal or experimental data.

Conclusion

This study enhances an understanding of dark personality traits, FoMO, cognitive ability, and online political participation, showing that psychopathy and FoMO consistently predict political engagement, while the effect of narcissism varies by context. Lower cognitive ability amplifies dark personality influences, highlighting the role of cognitive factors in online political participation. By identifying these complex pathways, this research offers a theoretical foundation for understanding how individual differences shape political participation in digital spaces.