Introduction

Art has long been seen as a reflection of society’s emotional and psychological states, from Plato’s notion of imitation1 to Hegel’s2 view of art as expressing societal development struggles. Others, like Nina Simone and Jean-Paul Sartre, also saw art as having a duty to address societal concerns3,4.

This philosophical discourse has recently extended into empirical research, shifting the focus from how art changes over time to whether specific artistic changes reflect broader societal phenomena. A growing body of research analyzes cultural artifacts (art, media, etc.) to gain insights into psychological traits and states5,6, proposing that these can be inferred from cultural consumption and production patterns7,8,9,10.

Such analyses align with posthumanistic approaches in psychology, which focus on human experience as reflected in cultural systems and artifacts, rather than relying solely on individual-centered measurements11. They provide an alternative to traditional, “present day”-based psychological research methods, with two main assets: they allow the analysis of collective emotional or cognitive trends by assessing the relationship between changing culture and society12,13, and they open a pathway for empirical historical-psychological research, which provides access to psychological patterns in past periods for which direct testing of subjects is no longer possible or where retrospective accounts would introduce significant hindsight bias5,14,15,16,17.

Music and poetry are art forms strongly associated with emotional expression18. They can be combined in songs with the textual components commonly referred to as lyrics. Music is especially interesting to analyze diachronically, as it is among the most widely consumed art forms19,20. The current average weekly music listening time has been reported as high as 21 h21. While there is no long-term data on whether music consumption has increased or decreased in recent history, it is evident that music has played a role in virtually every society for as long as recorded history exists22. Additionally, compared to other art forms, music has a relatively short production cycle and a higher variability in the number of different pieces consumed compared to visual art, literature, or movies23. While the instrumental component of music can be complex and ambiguous to analyze, the lyrical component is directly accessible as a measure that conveys explicit emotional content24.

Some studies have already utilized Natural Language Processing (NLP) to analyze songs both synchronically and diachronically, investigating whether societal phenomena are reflected in lyrics. For instance, previous research found increased sexist and profane language in popular lyrics in recent decades25,26,27,28. Others found a decrease in mentions of love and an increase in sexual language29,30. Moreover, one study found increased anger, egocentricity, and decreased language about social interactions, reflecting an increase in social isolation, since the 1990s31.

This research interest is not limited to the linguistic content of lyrics. Recent studies have investigated trends in lyrical complexity within popular music, revealing a gradual simplification over time. Findings indicate that songs with simpler lyrics tend to achieve greater commercial success than those with more complex lyrics32. This trend of decreasing complexity is evident in the lexical and structural complexity of lyrics33. Yet, few studies have directly combined diachronic lyric analysis with socioeconomic data.

In this study, we focus on the impact of significant societal shocks on the emotional and stress-related content of music lyrics. We specifically examine the effects of these events on the expression of positivity, stress, and complexity. Our approach emphasizes the consumption of music lyrics - how listeners emotionally engage with lyrical themes during times of societal upheaval, rather than the production of lyrics by artists. This distinction is essential, as consumption patterns can reveal broader audience needs and emotional responses to crises, such as a collective gravitation toward songs that mirror public sentiment or provide emotional relief. By analyzing the lyrics of the most popular songs surrounding these events, which reflect themes of stress, positivity, and lyrical complexity, we aim to understand how art mirrors societal stress and serves as a psychological tool for emotional regulation during times of crisis.

A relevant framework for understanding music consumption during periods of societal upheaval is Mood Management Theory34, which posits that individuals actively select media to regulate their emotions, often seeking content that aligns with or modulates their current mood. This theory, while traditionally applied at the individual level, suggests that during crises, listeners may be drawn to music that either resonates with heightened stress and anxiety or provides a sense of relief and distraction from it. For example, research shows that in the aftermath of traumatic events, individuals often choose music with darker or more contemplative tones, using it as a vehicle to process grief and distress35,36. Although research based on self-evaluation suggests that individuals use music for mood regulation to control or elevate their emotional state37, other studies indicate that listeners tend to select music aligned with their current affective state rather than a targeted one38,39. The present study builds on these findings to explore whether these individual-level behaviors of emotional-congruent art selection hold at a societal level, revealing how affective states during societal shocks influence music consumption and, potentially, the social function of music as a collective coping mechanism.

Some studies have already conducted diachronic analyses of music lyrics25,26,28,31,32,40. However, there are relevant gaps in this literature. First, most focus on limited timespans or specific genres, often neglecting the broader, diachronic perspective that could reveal long-term trends and responses to major societal events. Additionally, research to date has often relied on convenience samples of lyrics, selecting songs based on subjective criteria or availability rather than systematic sampling methods, which may limit generalizability and overlook broader trends in popular music consumption.

The present study addresses these limitations by analyzing the top 100 most-listened-to songs in the United States each week from 1973 to 2023, based on historical Billboard Hot 100 chart data (N ≈ 260,000 song-weeks). The US is particularly well-suited for this analysis, due to its large and diverse music market, as well as the availability of detailed, long-term chart data. Additionally, key societal events, such as 9/11, make it a relevant case for examining how music consumption reflects societal shocks. Furthermore, prior research in computational social science has often relied on US data, allowing for comparability while acknowledging the importance of extending such analysis to other cultural contexts in future work.

We employed NLP and compression algorithms to quantify changes in the stress-related language, positivity, and structural complexity of popular music lyrics. We specifically examined whether societal shocks, such as 9/11 (2001) and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), coincide with shifts in negative tone and stress expressions in lyrics. These two events were selected as significant time points due to their consistent reference to the most stressful years in recent American history, marked by widespread psychological, economic, and societal disruptions41,42. We also tested whether the median household income impacted song preferences, as economic downturns are associated with increased stress and anxiety among individuals43, and potentially influence cultural consumption habits.

Based on the literature reviewed above, we preregistered (https://osf.io/9e7au/) the hypotheses that H1) The use of stress-related language in popular music lyrics increased between 1973 and 2023 (H1a) and faster after major stressful events (post-2001 and post-2020) compared to periods before these events (H1b); H2) Sentiment in popular music lyrics has become more negative between 1973 and 2023 (H2a), and this trend increased faster after major stressful events (post-2001 and post-2020) compared to periods before these events (H2b); H3) Economic affluence (real median household income) predicts a decrease of stress-related language in popular music lyrics (H3a), and an increase of positive sentiment (H3b); Finally, we also predict that H4) The frequency of stress-related language in popular music lyrics negatively predicts lyrical complexity. After inspecting the data trends, we observed an interesting and unexpected shift in the complexity of music lyrics around 2016, coinciding with the election of Trump to his first presidential term, which was the most prevalent event at that time. Therefore, we additionally explored the effects of time on lyrical complexity and specifically examined the impact of the 2016 election.

Results

Stress, negativity, and simplicity increased in the long-term

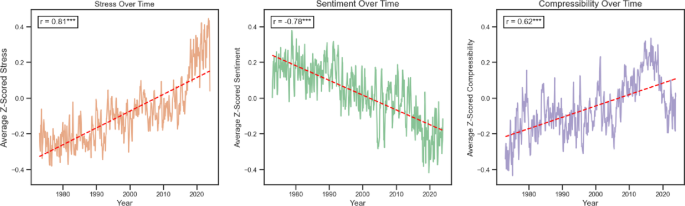

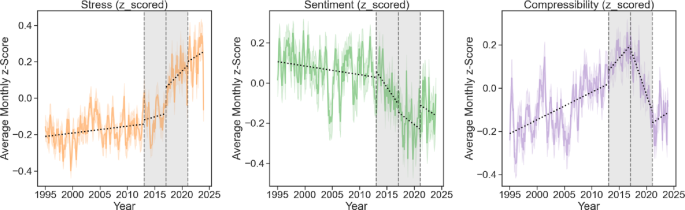

Consistent with hypothesis H1a, the monthly average frequency of stress-related language in popular music lyrics showed a strong positive correlation with time (r =.81, 95% CI [0.79, 0.84], p <.001). Similarly, supporting H2a, the monthly average sentiment in popular music lyrics correlated negatively with time (r = −.78, 95% CI [−0.81, − 0.75], p <.001). This suggests a substantial increase in stress-related and negative language from 1973 to 2023. We also found that compressibility increased over time (r =.62, 95% CI [0.57, 0.66], p <.001), suggesting that song lyrics became simpler. Trends are shown in Fig. 1. These relationships remained significant after controlling for temporal autocorrelations (Tables S1-S3).

Diachronic variations of Stress, Sentiment (Positivity), and Compressibility (inverse of Complexity) expressed in music lyrics throughout 1973–2023. Overall, the expression of stress, negativity, and simplicity has increased over the last 50 years

Societal shocks either co-occur with reduced stress, negativity, and simplicity or have no effect

For H1b, we ran regression analyses of stress-related language in popular music lyrics, focusing on the 24-month periods before and after 9/11 and early 2020 while excluding the week of each event (Fig. 2, left). Each model included three lagged dependent variables and applied Newey–West standard errors to account for autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity.

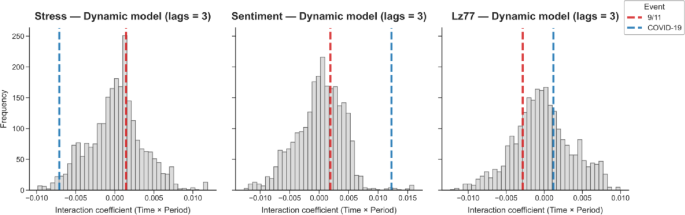

Variations of Stress, Sentiment (Positivity), and Compressibility (inverse of Complexity) expressed before and after societal shocks (9/11 and COVID). We found that (1) the onset of COVID-19 decreased stressful and negative language, and (2) 9/11 attenuated the rise of negative language (although this effect was less robust).

In the first analysis around 9/11, the overall model explained 78.3% of the variance in stress-related language (adjusted R² = 0.783). We found no significant main effect of time (β = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.001, 0.004], t(49) = 1.28, p = 0.208) and a non-significant effect of period (β = −0.03, 95% CI [−0.101, 0.042], t(49) = −0.84, p =.406). Moreover, the interaction time × period was not statistically significant (β = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.001, 0.004], t(49) = 0.977, p =.335) (Supplementary Table S4, Figure S2). This indicates that 9/11 did not significantly impact lyric’s stress.

In the second model, around the onset of COVID-19 in the US, the analysis yielded a lower adjusted R² of 0.475. Here, we found a small but significant interaction period × time (β = −0.007, 95% CI [−0.011, −0.003], t(49) = −3.626, p < 0.01) (Supplementary Table S5, Figure S3). However, this effect points in the opposite direction as hypothesized initially, suggesting an attenuation rather than an intensification in stress-related language following this event. In the empirical null analysis (Fig. 3), the observed interaction coefficient was more negative than 98% of all possible 4-year windows in our dataset, indicating that the magnitude of the COVID-19 effect was relatively uncommon in the broader temporal context. We found a significant effect of period (β = 0.173, 95% CI [0.082, 0.263], t(49) = 2.809, p <.001) and a significant effect of time (β = 0.004, 95% CI [0.001, 0.007], t(49) = 1.895, p =.008).

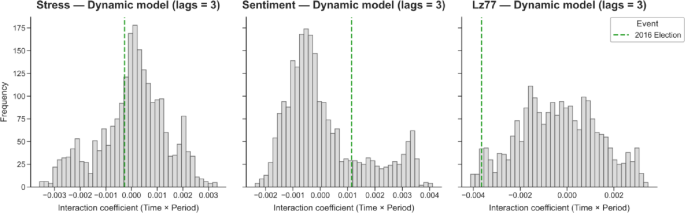

Empirical null distributions of the time × period interaction coefficients for Stress, Sentiment, and Compressibility (inverse Complexity). Each histogram shows the distribution of interaction coefficients from all possible 4-year windows (2 years before and after every potential center point). Dashed lines mark the observed effects for 9/11 (red) and COVID-19 (blue), indicating how unusual these event-related effects are relative to random temporal baselines.

For H2b, we replicated the analysis above, examining sentiment effects. The regression analyses showed similar trends, notably revealing that period × time interactions ran contrary to our hypothesis in both cases (Fig. 2, middle).

In the first analysis around 9/11, the overall model explained 59.4% of the variance in lyrical sentiment (adjusted R² = 0.594). We found a small, marginally non-significant positive period × time interaction (β = 0.002, 95% CI [−0.000, 0.004], t(49) = 1.946, p =.059), a non-significant effect of time (β = −0.001, 95% CI [−0.003, 0.000], t(49) = −1.605, p =.117), and a significant negative effect of period (β = −0.073, 95% CI [−0.135, −0.012], t(49) = −2.402, p =.021) (Supplementary Table S6, Figure S4).

In the second model, around the onset of COVID-19, the overall model explained 58.3% of the variance in lyrical sentiment (adjusted R² = 0.583). We found a significant positive period × time interaction (β = 0.012, 95% CI [0.006, 0.018], t(49) = 4.215, p <.001), indicating an increase in sentiment following the onset of the pandemic. The main effect of period was also significant and negative (β = −0.347, 95% CI [−0.489, −0.206], t(49) = −4.968, p <.001), while the effect of time was not significant (β = −0.003, 95% CI [−0.008, 0.001], t(49) = −1.484, p =.146) (Supplementary Table S7, Figure S5). The corresponding empirical null analysis (Fig. 3) showed that the observed interaction coefficient for COVID-19 is more positive than 99,4% of possible timepoints, indicating that such an effect is highly unlikely to occur by chance.

In addition to the pre-registered analysis of stress and sentiment, we conducted an exploratory examination of compressibility around 9/11 and 2020 (Fig. 2, right).

For the analysis around 9/11, the model explained 59.4% of the variance in lyrical compressibility (adjusted R² = 0.594). The interaction between time and period was negative but not statistically significant (β = −0.003, 95% CI [−0.009, 0.003], t(49) = −0.905, p =.371), indicating no clear shift in compressibility following 9/11. The main effects of time (β = 0.002, 95% CI [−0.003, 0.007], t(49) = 0.963, p =.341) and period (β = −0.023, 95% CI [−0.124, 0.079], t(49) = −0.450, p =.655) were also non-significant (Supplementary Table S8, Figure S6).

For the analysis around the onset of COVID-19, the model explained 85.6% of the variance in lyrical compressibility (adjusted R² = 0.856). The interaction between time and period was small and not statistically significant (β = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.003, 0.005], t(49) = 0.623, p =.537), indicating no differential change in compressibility after the onset of the pandemic. We found a strong negative effect of time (β = −0.008, 95% CI [−0.011, −0.005], t(49) = −5.066, p <.001), suggesting an overall decline in compressibility, while the main effect of period was non-significant (β = 0.008, 95% CI [–0.102, 0.118], t(49) = 0.146, p =.885) (Supplementary Table S9, Figure S7).

Median income growth does not predict stress, sentiment, or compressibility

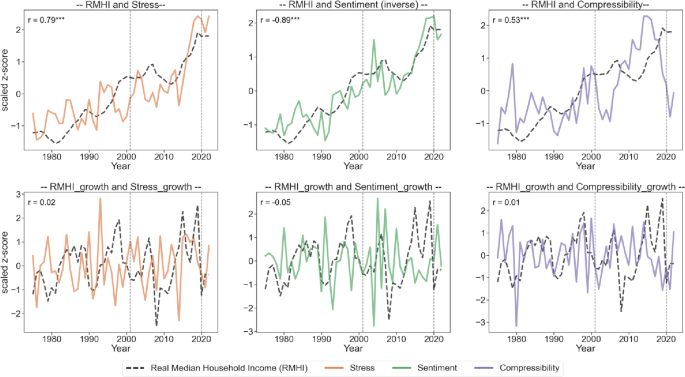

The results for Hypotheses H3a1, H3a2, H3b1, and H3b2, which proposed relationships between real median household income (RMHI) and stress-related language and sentiment in music lyrics, did not support the expected correlations (Fig. 4).

Relationship between Real Median Household Income (RMHI) and yearly Lyrics Variables. (Top) The raw data showed significant correlations between RMHI and stress, sentiment, and compressibility (inverse of complexity). (Bottom) However, when analyzing the yearly growth of these variables, these effects did not survive.

The raw correlations between yearly RMHI and stress-related language were strong and positive (r =.79, 95% CI [0.65, 0.88], p <.001), while RMHI and sentiment showed a strong negative correlation (r = −.89, 95% CI [−0.94, − 0.81], p <.001). However, when we corrected for long-term temporal trends, there were no significant relationships between yearly RMHI growth and yearly stress levels (r =.17, 95% CI [−0.12, 0.43], p =.247) or yearly stress growth (r =.02, 95% CI [−0.26, 0.3], p =.885). Similarly, yearly RMHI growth was not significantly correlated with yearly sentiment levels (r = −.27, 95% CI [−0.51, 0.02], p =.063) or yearly sentiment growth (r = −.05, 95% CI [−0.33, 0.24], p =.745). Contrary to our hypotheses, these findings suggest that yearly fluctuations in RMHI growth do not substantially impact stress or sentiment language trends within popular music lyrics over time.

Exploratorily, we also investigated the relationship between yearly compressibility and yearly RMHI. While there was a significant positive raw correlation between yearly RMHI and yearly compressibility (r =.53, 95% CI [0.31, 0.71], p <.001), there was neither a significant correlation between yearly RMHI growth and yearly compressibility (r = −.27, 95% CI [−0.51, 0.02], p =.063) nor yearly compressibility growth (r =.01, 95% CI [−0.27, 0.30], p =.922).

Because correlations between time series can be obscured when these are out of phase, we performed exploratory cross-correlation analyses between RMHI, stress, sentiment, and compressibility (Supplementary Figure S11) after detrending and scaling the time series.

The best lags for stress (3 years) and sentiment (8 years) indicated their precedence over RMHI. However, the best cross-correlations were not significant (stress: r =.23, p =.107; sentiment: r =.21, p =.141), suggesting no notable lagged effects between economic affluence and stress- or sentiment-related language in popular music lyrics.

Conversely, the best lag for compressibility suggests it is preceded by RMHI (−9 years). However, the p-value was marginally non-significant (stress: r =.27, p =.058) and contrary to the prediction that rising income would increase preference for more complex songs.

While both stress and simplicity increase in the long-term, they are anti-correlated

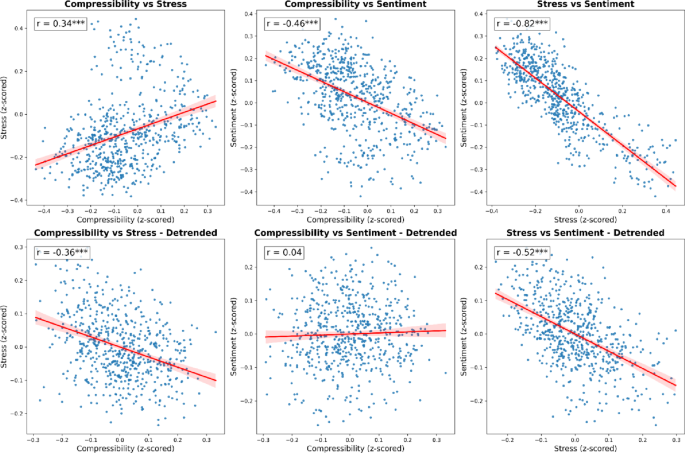

For Hypothesis H4, we examined the correlations between monthly average stress-related language, sentiment, and compressibility (LZ77) in popular music lyrics. The analysis revealed a positive correlation between compressibility and stress (r =.34, 95% CI [0.27, 0.41], p <.001). Conversely, there was a negative correlation between compressibility and sentiment (r = −.46, 95% CI [−0.52, − 0.4], p <.001). Notably, a strong negative correlation was found between stress and sentiment (r = −.82, 95% CI [−0.84, − 0.79], p <.001). This indicates that times with higher stress and negativity in lyrics were correlated with lower lyrical complexity (higher compressibility).

However, when we repeated the analysis detrending the time series and controlling for long-term time effects, we found a significant negative relationship between monthly average stress and sentiment (r = −.52, 95% CI [−0.57, − 0.46], p <.001) and a significant negative correlation between stress and compressibility (r = −.36, 95% CI [−0.43, − 0.29], p <.001). The correlation between compressibility and sentiment turns non-significant when controlling for time (r =.04, 95% CI [−0.04, 0.12], p =.357). Scatterplots with trendlines for the correlations are shown in Fig. 5.

Relationship between Compressibility (inverse of Complexity), Stress, and Sentiment in Popular Music Lyrics. (Top) We observed significant positive correlations between compressibility and stress and significant negative correlations between sentiment and both compressibility and stress. (Bottom) However, after detrending for time, the correlation between compressibility and sentiment became non-significant, while the correlation between compressibility and stress became negative.

Complexity in song lyrics might have increased during Trump’s presidency

A previous study on the complexity of song lyrics indicated a monotonic decrease over time. However, that study covered a sample of lyrics up to 201632. After inspecting our data, we observed a potential inflection of compressibility after 2016. Thus, we performed an exploratory post hoc analysis of the trends during the second term of the Obama presidency (20 January 2013 to 19 January 2017) compared to the first term of the Trump presidency (20 January 2017 to 19 January 2021) (Fig. 6).

Variations of Stress, Sentiment (Positivity), and Compressibility (inverse of Complexity) during the Obama and Trump presidencies. Lyrics expressed rising complexity during Trump’s presidency vs. Obama’s.

For stress, we found a non-significant positive effect of period (β = 0.049, 95% CI [−0.041, 0.138], t(93) = 1.079, p =.284), and a small but significant positive effect of time (β = 0.001, 95% CI [0.000, 0.002], t(93) = 2.038, p =.045). The interaction between period and time was also not significant (β = −0.000, 95% CI [−0.002, 0.001], t(93) = −0.325, p =.746). The model explained 85.5% of the variance (adjusted R² = 0.855) (Supplementary Table S10, Figure S8).

For sentiment, we found a significant negative effect of time (β = −0.002, 95% CI [−0.003, −0.001], t(93) = −3.458, p <.001), indicating a continuous decrease in sentiment over time. Period (β = −0.073, 95% CI [−0.170, 0.024], t(93) = −1.496, p =.138) and the interaction (β = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.000, 0.003], t(93) = 1.390, p =.168) were not significant. The model accounted for 75.1% of the variance (adjusted R² = 0.751) (Supplementary Table S11, Figure S9).

For compressibility, we found a significant negative period × time interaction (β = −0.004, 95% CI [−0.006, −0.001], t(93) = −3.213, p =.002). We also observed marginally significant positive main effects of time (β = 0.001, 95% CI [−0.000, 0.002], t(93) = 1.773, p =.080) and significant effects of period (β = 0.168, 95% CI [0.055, 0.281], t(93) = 2.945, p =.004). The model showed a strong fit to the data (adjusted R² = 0.826) (Supplementary Table S12, Figure S10). The corresponding empirical null analysis (Fig. 7) showed that the observed interaction coefficient was more negative than 97.9% of all possible timepoints, suggesting that such an effect would be highly unlikely to arise by chance.

Empirical null distributions of the time × period interaction coefficients for Stress, Sentiment, and Compressibility (inverse Complexity). Each histogram shows the distribution of interaction coefficients from all possible 4-year windows (2 years before and after every potential center point). Dashed lines mark the observed effects for 2016 (green), indicating how unusual these event-related effects are relative to random temporal baselines.

Discussion

We observed that stress-related language, negativity, and lyrical simplicity increased significantly over the long term. However, contrary to our expectations, these trends did not amplify after societal shocks such as 9/11 or the COVID-19 pandemic; instead, the trends either attenuated or had no measurable effect. These findings likely reflect shifts in music preferences rather than production, as Billboard rankings capture what listeners chose to engage with during these periods. Interestingly, real median household income fluctuations showed no predictive value for stress, sentiment, or lyrical complexity, even after accounting for time lags. Notably, while both stress and simplicity increased over time, they exhibited a negative relationship when detrended for time, suggesting that higher stress corresponded to more complex lyrics. As expected, stress and sentiment were negatively correlated. Finally, a post hoc exploratory analysis revealed that during Trump’s presidency, lyrical complexity increased, marking a distinct deviation from earlier trends. Now, we discuss these findings.

First, we observed a significant increase in stress-related language and negativity over the past five decades. These findings are congruent with increasing rates of depression, anxiety, and stress44,45 and mirror similar trends of rising negative tone in news media46 and fiction books47,48. In line with Varnum et al.32, we also found a decrease in lyric complexity, congruent with recent drops in IQ and PISA test scores49,50. While the increase in stress, negativity, and simplicity in lyrics may reflect mood-congruent trends in societal mental health51, they may also result from general shifts in language use and evolving societal norms, or most likely a combination32,47,48.

Second, contrary to our hypotheses, periods following a major societal shock (the onset of COVID-19) were associated with a decline in the consumption of stressful and negative lyrics, compared to periods preceding this shock. While positive sentiment also increased after 9/11, this effect was less robust, perhaps because it was a single event rather than a prolonged shock.

This pattern is consistent with the idea of emotional modulation through art, though causality cannot be inferred. In extreme events, people might prefer music with less stressful and more positive lyrical content to modulate their mood or emotional state. These results align with recent data on Japanese song lyrics consumption52 and with Zillmann’s Mood Management Theory34, which posits that people in aversive states seek out positive stimuli to enhance their well-being hedonically53. This effect has been particularly pronounced when participants seek to cope with stressors through avoidance54, which might be the case during shocks. While this theory was originally proposed for individual media consumption, our findings may reflect a similar phenomenon at a collective level.

Third, median income rises over time, along with stress, negativity, and simplicity. However, median income growth was not significantly associated with stress, negativity, or simplicity, even after accounting for potential time lags. These results should be interpreted as correlational; while the temporal alignment of these variables can inform hypotheses about broader sociocultural relationships, the analyses do not establish directionality or causation. This disconnect may partly stem from a misalignment between the perceived economic situation and actual economic indicators. While measures such as median household income or GDP growth provide an objective view of economic conditions55, individuals often base their emotional and behavioral responses on their subjective experiences and perceptions of the economy56. Factors such as job security, cost of living, or exposure to media narratives can significantly influence how people perceive their financial stability, even in times of broader economic prosperity57,58. For example, during periods of economic growth, rising inequality or localized economic struggles may lead to widespread feelings of dissatisfaction or stress, despite positive macroeconomic trends59. These subjective factors might partially explain the discrepancy between US and Japanese data. In the latter, economic hardship was found to predict positivity52. Further exploration between socio-economic trends and song consumption is required.

Finally, our finding of increasing lyric simplicity over time aligns with Varnum et al.‘s data32, though our results indicate a weaker effect. This discrepancy may be due to differences in the analyzed periods. Varnum et al. examined a dataset from 1958 to 2016, whereas our study focused on lyrics between 1973 and 2023. Notably, we observed a reversal of the trend toward decreasing complexity, beginning in 2016. Our post hoc analysis suggests that lyrical complexity increased during Trump’s first term compared to Obama’s second term. This result is interesting but should be taken cautiously, as this work was not designed to systematically test the effects of political cycles. While Trump’s election sparked several cultural reactions60,61, future research should explore the potential drivers of this complexity reversal and whether similar patterns emerge in other media and political cycles. Furthermore, this temporal association should not be interpreted as evidence of a causal effect, particularly given the overlap with other events such as the onset of COVID-19.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the sparse availability of data on popular music consumption outside the US, our findings are confined to its cultural and historical context. However, our results broadly align with those of a recent study on Japanese songs52. Second, this study only focused on the textual component of music. Previous research has shown that combining sentiment analysis of lyrics and audio provides more reliable sentiment measures62. Thus, future multimodal research might provide a more comprehensive understanding of how song features relate to societal mood.

While the study applies a quasi-experimental, interrupted time-series approach to examine changes surrounding major societal events, the analyses remain observational in nature. Thus, any observed differences before and after events such as 9/11 or COVID-19 represent temporal associations, not definitive causal effects.

Another potential limitation is the sampling bias inherent in using the Billboard Hot 100 to measure song popularity and overall consumption. While this list provides a robust indicator of mainstream success, it systematically underrepresents certain genres and subcultures, particularly in their early stages. For example, before the mainstream breakthrough of Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight, hip-hop was primarily distributed via mixtapes, bypassing traditional sales and airplay metrics63. Similarly, early punk rock, led by bands like The Ramones and the Sex Pistols, faced censorship on radio due to its anti-establishment themes64. Additionally, genres like early EDM, reggaeton, and Latin music achieved significant underground success in rave and club cultures. Still, they were underrepresented on charts due to their informal and grassroots distribution methods65. Furthermore, despite achieving significant commercial success in the 1980 s, heavy metal may still be underrepresented in airplay due to censorship and societal pushback against its controversial themes66. This bias may skew our findings, as the data disproportionately reflects the consumption patterns of mainstream audiences while underestimating the influence and reach of specific subcultures.

A small number of songs were also excluded due to non-English lyrics or incorrect scraping returns. Given their low proportion and random distribution, these omissions are unlikely to have systematically biased the results. In addition, changes in genre popularity over time may have contributed to some of the observed variation in stress, sentiment, and lyrical complexity. However, we interpret these genre shifts not merely as confounding factors but as reflections of changing audience preferences under different societal conditions. Cross-cultural or genre-controlled analyses would be valuable future extensions to further disentangle these effects.

Finally, the timeframe of Trump’s presidency partially overlaps with the onset of COVID-19, introducing a potential confound in the exploratory analysis.

In summary, this study illustrates associations between lyrical patterns and societal context, highlighting music’s potential role in reflecting collective emotional states using NLP. Analyzing stress and sentiment trends in popular music lyrics from 1973 to 2023, we observed a rising prevalence of stress-related language and negativity. Surprisingly, during major societal events like the COVID-19 pandemic, music consumption trends coincided with patterns consistent with emotional modulation and escapism67 rather than emotion-congruent selections, highlighting the complex ways people use music to navigate collective stress. This is further supported by findings that listening to happy music was associated with improved mood and lower stress levels during the COVID-19 lockdown, especially among individuals experiencing heightened chronic stress68. Additionally, the positive correlation between stress and lyric complexity suggests that individuals may gravitate toward more cognitively demanding music during stressful periods. Finally, the absence of a link between lyric sentiment or stress and economic growth indicates that economic affluence may not directly shape music consumption. These findings enrich our understanding of music as a unique tool for emotional regulation and underscore its significance in shaping and reflecting societal moods across time.

Methods

To examine changes in stress, sentiment, and complexity of popular music’s lyrics over 50 years, we collected the weekly top 100 songs from the Billboard Hot 100 chart for each week between 1973 and 2023. The Billboard Hot 100 ranks songs based on a combination of sales, radio airplay, and streaming activity, meaning that a song’s appearance in the chart reflects its popularity at that time rather than its release date69. We retrieved the lyrics for each song and computed stress, sentiment, and complexity scores, as described in detail in the following sections. Then, we modeled score changes over the 50 years and differences before vs. after major stressful events (9/11/2001 terrorist attacks and US COVID-19 onset in 2020). Additionally, we retrieved the real median household income from the Federal Reserve Economic Data70 and compared its yearly changes with those of popular music lyrics’ stress, sentiment, and complexity. The study, including all hypotheses and methodological procedures, was preregistered on OSF (https://osf.io/9e7au/).

Data collection and preprocessing

All data collection, transformation, and analysis were conducted using Python. We scraped the top 100 songs of each week between 1973 and 2023 from the Billboard Hot 100 chart69 using BeautifulSoup71. This process resulted in 266,086 entries on the Billboard Hot 100 list, one for each song and week, with multiple entries for songs remaining multiple weeks. This means that long-lasting hits contributed multiple data points, while songs that only charted for a single week appear only once. Using the song titles and artist names as search queries, we obtained the lyrics of each song through the Lyrics.ovh72 and Genius API73, excluding purely instrumental songs. To filter out incorrect returns that were not lyrics, we checked all retrieved lyrics for length and the presence of special characters. We also removed metadata and inserts like “[Chorus]” from the lyrics. We then excluded songs with non-English lyrics from the dataset, as our study focuses exclusively on lyrics in English to ensure consistent linguistic processing and comparability. Sentiment and stress-related language analysis tools are optimized for a single language, and including lyrics in multiple languages would introduce inconsistencies in interpretation and analysis. Additionally, as our study examines lyrics trends in the US, limiting the dataset to English lyrics aligns with the predominant language of Billboard’s audience and ensures the reliability of our results. In total, 930 songs (4.32%) were excluded due to instrumental or incorrect scraping returns, and 414 songs (1.92%) due to non-English lyrics. After removing incorrect returns, we obtained 20,186 individual song lyrics (without duplicates). Finally, we tokenized (split the lyrics into individual words and phrases) and lemmatized (reduced words to their base or dictionary form) the lyrics – standard preprocessing steps for meaningful text analysis74.

We computed the frequencies of stress-related words in each lyric using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) tool75 and calculated each lyric’s sentiment (positive vs. negative) using a custom Python script, leveraging a compound score from the VADER sentiment analysis tool76. The VADER compound score provides a continuous sentiment value ranging from − 1 (most negative) to + 1 (most positive), with 0 representing neutral sentiment. We chose VADER over other sentiment analysis tools because it performs better with short and informal texts77,78, making it particularly effective for lyrics from the late 20th century onward, as they increasingly feature colloquial language and slang. While VADER was originally trained using contemporary social media language76, it has been applied in various domains and across different eras79,80. Another advantage of VADER is that, even though it is a lexical-based sentiment analysis tool, it takes into account context such as negation, intensifiers, and polarity reversal.

Each song was assigned one overall sentiment score and one overall stress score, each representing the average across all words in that song. Thus, differences in lyric length do not influence these measures, ensuring that observed trends reflect changes in lyrical tone rather than variations in text quantity.

To quantify the redundancy and structural complexity of the lyrics, we computed the LZ77 compressibility score for each lyric in the dataset in line with recent research32,33. The LZ77 algorithm is a fundamental lossless data compression technique that identifies and replaces repeated data occurrences with references to earlier instances in the uncompressed data stream81. By measuring the compressibility of the lyrics, we aimed to assess the level of repetition and predictability within them.

We implemented the LZ77-based compressibility calculation using Python’s zlib package82, which provides efficient compression algorithms. Each song lyric was first stripped of any leading and trailing whitespace and converted to a byte string using UTF-8 encoding. The original size of the lyric was calculated based on the length of this byte string. The byte string was then compressed by applying the DEFLATE algorithm, implementing LZ77. The size of the compressed data was determined by calculating the length of the compressed byte string. The compressibility score was calculated as the ratio between the compressed size and the original size, expressed as:

$$\:Compression\:Ratio\:\left(LZ77\right)=\:\frac{Original\:Size\:\left(bytes\right))}{Compressed\:Size\:(bytes}$$

A lower compression ratio indicates higher redundancy, implying more repetition within the lyrics, while a higher compression ratio suggests lower redundancy and potentially greater complexity. This approach allowed us to calculate the LZ77 compressibility score for each lyric to measure its structural complexity in terms of repetition and predictability. As a validation, we compared LZ77 compressibility values with three measures of lexical diversity moderately to strongly with three distinct measures of lexical diversity (Supplementary Figure S1).

The data collection and preprocessing scripts and the raw dataset can be found at https://osf.io/2k7ut/.

Analysis

Confirmatory analysis (pre-registered)

We conducted statistical analyses to test our hypotheses regarding trends in stress-related language, sentiment, and complexity in popular music lyrics from 1973 to 2023. All variables were standardized using z-scores, and outliers exceeding three standard deviations from the mean were excluded to reduce the influence of extreme values on the overall trend estimation. In total, 461 unique songs (2.28%) were excluded for stress, none for sentiment (0.00%), and 159 (0.79%) for LZ77 complexity. Given the small proportion of excluded data, this procedure had no meaningful impact on the results, as all main findings remained consistent when analyses were rerun including outliers.

For Hypotheses 1a and 2a, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients between time (measured in months since January 1973) and both stress and sentiment scores. While Pearson correlation coefficients provide a useful descriptive measure of the strength and direction of the trend, temporal autocorrelations in the data may bias the associated p-values. Therefore, these results should be interpreted primarily regarding effect size and direction. As a robustness check, we additionally estimated ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with lagged dependent variables and Newey–West standard errors83 to account for heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation. These models reaffirmed the presence and direction of the long-term trends observed in the Pearson correlation analyses (Supplementary Tables S1-S3).

To test Hypotheses 1b and 2b, we performed linear regression analyses with interaction terms to compare the slopes of monthly stress-related language and sentiment before and after the 9/11 attacks and the onset of COVID-19 in the US in January 2020. Following best practices in interrupted time series research84,85, we defined and pre-registered “pre-event” and “post-event” periods as the two years before and after each event, excluding the event week because our data is recorded weekly. In this context, the term interrupted does not refer to disruptions in music production or access, but to potential changes in listeners’ preferences for lyrical tone and stress expression following major societal shocks. To reduce short-term noise, we used monthly averages as the unit of analysis, which aligns with our focus on broader temporal trends and improves the stability of slope estimates in interrupted time series models. This decision aligns with prior simulation-based power analyses, which suggest that 24 pre- and 24 post-event time points (48 total) provide sufficient power to detect moderate-to-large effects in ITS models85. Extending the time window too far before or after the event increases the risk of confounding due to unrelated long-term trends. Furthermore, a larger window increases the probability of detecting a false positive simply due to the increased sample size rather than a meaningful effect. Additionally, excluding the event week helps minimize short-term anomalies, which could otherwise introduce bias into trend estimation. The dependent variables were stress-related language and sentiment scores; independent variables included time, period (pre-event vs. post-event), and their interaction.

Initial residual diagnostics, using the Durbin-Watson statistic86, ACF/PACF plots, and the Ljung-Box test87, revealed autocorrelation in the residuals. As preregistered, we report the results from the original OLS models. However, the main analyses now report results from dynamic OLS models that incorporate three lagged dependent variables and apply Newey–West (HAC) standard errors to correct for autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity83. We selected three lags for the main robustness checks, based on minimizing residual autocorrelation and optimizing model fit according to the Bayesian Information Criterion88. This specification effectively addresses residual dependencies while maintaining model stability. The originally preregistered OLS models are reported in the Supplementary Materials for transparency. All effects reported as significant in the dynamic OLS models remained significant in the preregistered OLS models, whereas a few effects that were significant in the simple models became non-significant after correcting for autocorrelation. Because the data were aggregated monthly, each lag represents one month. The resulting short-term autoregressive effects reflect temporal adjustment processes in monthly lyric data but do not affect the primary analyses, which focus on long-term trends and event-related slope changes. Full dynamic OLS models including 1 to 3 lags are shown in Supplementary Tables S4-S12. Residual normality distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality and visual inspection of the plotted data.

For the comparison of language trends around major events, sample sizes and date ranges for each period were as follows:

-

Pre-9/11: 8 September 1999 to 8 September 2001, n = 9 575.

-

Post-9/11: 17 September 2001 to 17 September 2003, n = 9 958.

-

Pre-COVID-19 US onset: 19 January 2018 to 19 January 2020, n = 9 982.

-

Post-COVID-19 US onset: 27 January 2020 to 27 January 2022, n = 9 669.

This resulted in a total pre-event sample size of 19 557 and a post-event sample size of 19 627.

To evaluate whether the observed event effects could plausibly arise by chance, we additionally conducted an empirical null analysis. Specifically, we re-estimated the same dynamic OLS model for all possible 4-year windows in the dataset (2 years before and after each potential center point) to obtain a distribution of possible effect sizes. The resulting distributions provide a descriptive temporal baseline, allowing us to contextualize the magnitude of the observed effects relative to all other possible time windows.

For Hypotheses 3a and 3b, we examined the relationship between economic affluence and linguistic features by analyzing annual real median household income growth rates from the Federal Reserve Economic Data70. We aggregated stress-related language frequencies and sentiment scores annually and conducted Pearson correlation analyses between these linguistic measures and the yearly growth of real median household income.

To address Hypothesis 4, we calculated the LZ77 compression ratio for each song lyric as a measure of lyrical complexity, where a lower ratio indicates higher redundancy (more repetition). We then performed correlation analyses between the average monthly compressibility scores, stress scores, and sentiment scores to assess whether higher frequencies of stress-related language are associated with less complex lyrics.

We used the scipy package89 for general statistical analyses, the statsmodels90 package for linear regression analyses, and the pingouin91 package for calculating partial correlations. Statistical significance was set at p <.05. All scripts and datasets are available at .

Exploratory analysis

In addition to our pre-registered hypotheses, we conducted exploratory analyses. All regression analyses for stress and sentiment were also performed for compressibility. To account for the strong correlations of the psychological variables over time, we calculated detrended correlations by including time as a covariate in the analysis. Furthermore, we performed cross-correlation analyses to test whether there is a time lag between real median household income and stress, positivity, and compressibility in lyrics. This analysis was done in R with the forecast package92. We identified significant lagged effects between the variables by addressing trends and autocorrelations.

Finally, after inspecting the data trends, we found an interesting (and surprising) inflection of compressibility around 2016. Thus, we performed exploratory post hoc linear regression analyses with interaction terms to compare the slopes of monthly stress-related language, sentiment, and compressibility during the second term of Barack Obama’s presidency vs. the first term of Donald Trump’s presidency, excluding the week of the presidential transition. The pre-2017 period (January 20, 2013, to January 12, 2017) included 19,996 individual songs (duplicates excluded), while the post-2017 period (January 28, 2017, to January 20, 2021) included 19,762 individual songs (duplicates excluded).

Data availability

All data and analysis scripts used in this study are openly available on the Open Science Framework (OSF) at: https://osf.io/2k7ut.

References

Plato. Republic. (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Hegel, G. W. F. Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art (T. M. Knox, Trans) (Clarendon, 1975).

Sartre, J. P. What Is Literature? (Philosophical Library, 1949).

Simone, N. & Cleary, S. I Put a Spell on You: the Autobiography of Nina Simone (Pantheon Books, 1991).

Atari, M. & Henrich, J. Historical psychology. Current Dir. Psychol. Science, 32, 176–183 (2023).

Baumard, N., Safra, L., Martins, M. & Chevallier, C. Cognitive fossils: using cultural artifacts to reconstruct psychological changes throughout history. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28(2), 172–186 (2023).

Anderson, I. et al. Just the way you are: linking music listening on spotify and personality. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 12, 561–572 (2021).

Annalyn, N., Bos, M. W., Sigal, L., & Li, B. Predicting personality from book preferences with user-generated content labels. IEEE Trans. on Affect. Comput. 11, 482–492 (2020).

Greenberg, D. M. et al. Universals and variations in musical preferences: A study of Preferential reactions to Western music in 53 countries. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 122, 286–309 (2022).

Rentfrow, P., Goldberg, L. & Zilca, R. Listening, Watching, and reading: the structure and correlates of entertainment preferences. J. Pers. 79, 223–258 (2011).

Wolfe, C. What Is Posthumanism? (U of Minnesota, 2010).

Chauhan, A., Belhekar, V., Sehgal, S., Singh, H. & Prakash, J. Tracking collective emotions in 16 countries during COVID-19: a novel methodology for identifying major emotional events using Twitter. Front Psychol. 14, 1105875 (2024).

Garcia, D. & Rimé, B. Collective emotions and social resilience in the digital traces after a terrorist attack. Psychol. Sci. 30, 617–628 (2019).

Baumard, N. Psychological origins of the Industrial Revolution: More work is needed!. Behavioral Brain Sci. 42, e189 (2019).

Jackson, J. C., Gelfand, M., De, S. & Fox, A. The loosening of American culture over 200 years is associated with a creativity–order trade-off. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 244–250 (2019).

Martins, M., Baumard, N. & J. D. & The rise of prosociality in fiction preceded Democratic revolutions in early modern Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 117, 28684–28691 (2020).

Martins, M. & Baumard, N. How to develop reliable instruments to measure the cultural evolution of preferences and feelings in history? Front Psychol. 13, 786229 (2022).

Juslin, P. N. & Västfjäll, D. Emotional responses to music: the need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behav. Brain Sci. 31, 559–575 (2008).

National Endowment For The Arts & United States. Bureau Of The Census. Survey of Public Participation in the Arts (SPPA), United States, 2022: Version 1. ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research (2024).

North, A., Hargreaves, D. & Hargreaves, J. Uses of music in everyday life. Music Percept. 22, 41–77 (2004).

IFPI Engaging With Music: The largest music study of its kind – Ifpi Sverige. (2023). Report https://www.ifpi.se/2023/12/11/engaging-with-music/ (2024).

Schulkin, J. & Raglan, G. B. The evolution of music and human social capability. Front. Neurosci. 8, 292 (2014).

Vogel, H. L. Entertainment Industry Economics: A Guide for Financial Analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2014).

Ali, S. O. & Peynircioğlu, Z. F. Songs and emotions: are lyrics and melodies equal partners? Psychol. Music. 34, 511–534 (2006).

Adams, T. & Fuller, D. The words have changed but the ideology remains the same: misogynistic lyrics in Rap music. J. Black Stud. 36, 938–957 (2006).

Betti, L., Abrate, C. & Kaltenbrunner, A. Large scale analysis of gender bias and sexism in song lyrics. EPJ Data Sci. 12, 10 (2023).

Logan, B., Kositsky, A. & Moreno, P. Semantic Analysis of Song Lyrics. (2004).

Muhammad, M., Goyak, F., Zaini, M. & Ibrahim, W. Diachronic analysis of the profane words in english song lyrics: A computational linguistics perspective. Malaysian J. Music. 11, 14–32 (2022).

Hall, P., West, J. & Hill, S. Sexualization in lyrics of popular music from 1959 to 2009: implications for sexuality educators. Sexuality Culture 16, 103–117 (2011).

Madanikia, Y. & Bartholomew, K. Themes of lust and love in popular music lyrics from 1971 to 2011. SAGE Open 4 (2014).

DeWall, C., Pond, J., Richard, Campbell, W. K. & Twenge, J. Tuning in to psychological change: linguistic markers of psychological traits and emotions over time in popular U.S. Song lyrics. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativity Arts. 5, 200–207 (2011).

Varnum, M. E. W., Krems, J. A., Morris, C., Wormley, A. & Grossmann, I. Why are song lyrics becoming simpler? A time series analysis of lyrical complexity in six decades of American popular music. PLoS ONE. 16, e0244576 (2021).

Parada-Cabaleiro, E. et al. Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades. Sci. Rep. 14, 5531 (2024).

Zillmann, D. Mood management through communication choices. Am. Behav. Sci. 31, 327–340 (1988).

Knobloch, S. & Zillmann, D. Appeal of love themes in popular music. Psychol. Rep. 93, 653–658 (2003).

Van den Tol, A. J. M. & Edwards, J. Exploring a rationale for choosing to listen to sad music when feeling sad. Psychol. Music. 41, 440–465 (2013).

Saarikallio, S. & Erkkilä, J. The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychol. Music. 35, 88–109 (2007).

Saarikallio, S. Music as emotional self-regulation throughout adulthood. Psychol. Music. 39, 307–327 (2011).

Thoma, M. V., Ryf, S., Mohiyeddini, C., Ehlert, U. & Nater, U. M. Emotion regulation through listening to music in everyday situations. Cogn. Emot. 26, 550–560 (2012).

Napier, K. & Shamir, L. Quantitative sentiment analysis of lyrics in popular music. J. Popular Music Stud. 30, 161–176 (2018).

O’Kane, C. was a difficult year for many, but according to historians, it’s not the most stressful year in U.S. history - CBS News. (2020). https://www.cbsnews.com/news/most-stressful-years-american-history/ (2020).

Stress in America™ 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report-october (2020).

Muntaner, C., Eaton, W. W., Miech, R. & O’Campo, P. Socioeconomic position and major mental disorders. Epidemiol. Rev. 26, 53–62 (2004).

Brignone, E. et al. Trends in the diagnosis of diseases of despair in the united States, 2009–2018: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 10, e037679 (2020).

Dykxhoorn, J. et al. Temporal patterns in the recorded annual incidence of common mental disorders over two decades in the united kingdom: a primary care cohort study. Psychol. Med. 54, 663–674 (2024).

Rozado, D., Hughes, R. & Halberstadt, J. Longitudinal analysis of sentiment and emotion in news media headlines using automated labelling with transformer Language models. PLOS ONE. 17, e0276367 (2022).

Acerbi, A., Lampos, V. & Bentley, R. A. Robustness of emotion extraction from 20th century English books. In IEEE International Conference on Big Data 1–8 (2013).

Morin, O. & Acerbi, A. Birth of the cool: a two-centuries decline in emotional expression in Anglophone fiction. Cogn. Emot. 31, 1663–1675 (2017).

Dworak, E. M., Revelle, W. & Condon, D. M. Looking for Flynn effects in a recent online U.S. Adult sample: examining shifts within the SAPA project. Intelligence 98, 101734 (2023).

OECD. Long-term trends in performance and equity in education. PISA 2022 Results (Volume I): The State of Learning and Equity in Education. (2023).

Luong, K. T. & Knobloch-Westerwick, S. Selection of entertainment media: from mood management theory to the SESAM model. In The Oxford Handbook of Entertainment Theory 159–180 (Oxford University Press, 2021).

Masui, H. & Miyamoto, Y. Emotions in Japanese song lyrics over 50 years: trajectory over time and the impact of economic hardship and disasters. Curr. Res. Ecol. Social Psychol. 8, 100218 (2025).

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. Mood management Theory, Evidence, and advancements. in Psychology of Entertainment (Routledge, (2006).

Stevens, E. M. & Dillman Carpentier, F. R. Facing our feelings: how natural coping tendencies explain when hedonic motivation predicts media use. Communication Res. 44, 3–28 (2017).

Nolan, B. The median versus Inequality-Adjusted GNI as core indicator of ‘Ordinary’ household living standards in rich countries. Soc. Indic. Res. 150, 569–585 (2020).

García-Sánchez, E. et al. Perceived economic inequality is negatively associated with subjective Well-being through status anxiety and social trust. Soc. Indic. Res. 172, 239–260 (2024).

Griep, Y. et al. The effects of unemployment and perceived job insecurity: a comparison of their association with psychological and somatic complaints, self-rated health and life satisfaction. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 89, 147–162 (2016).

Malika, M., Maheswaran, D. & Jain, S. P. Perceived financial constraints and normative influence: discretionary purchase decisions across cultures. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 50, 252–271 (2022).

Rochat, M. The determinants of growing economic inequality within advanced democracies. Int. Rev. Econ. 70, 457–475 (2023).

Crandall, C. S., Miller, J. M. & White, M. H. Changing norms following the 2016 U.S. Presidential election: the Trump effect on prejudice. Social Psychol. Personality Sci. 9, 186–192 (2018).

Gantt Shafer, J. Donald trump’s political incorrectness: neoliberalism as frontstage racism on social media. Social Media + Soc. 3, 2056305117733226 (2017).

Schaab, L. & Kruspe, A. Joint sentiment analysis of lyrics and audio in music. (2024).

French, K. Geography of American Rap: Rap diffusion and Rap centers. GeoJournal 82, 259–272 (2017).

Wright, L. & Enjoy It Destroy It? 40 Years of Punk Rock Scholarship. In The Oxford Handbook of Punk Rock (eds McKay, G. & Arnold, G.) (Oxford University Press, 2020).

Wilkins, A. Rave culture: the alteration and decline of a Philadelphia music scene by Tammy L. Anderson. American Ethnologist. 37 (2010).

Ratcliffe, G. M. & Parental Advisory Explicit Content: Music Censorship and the American Culture Wars (Oberlin College, 2016).

Stenseng, F., Rise, J. & Kraft, P. Activity engagement as escape from self: the role of Self-Suppression and Self-Expansion. Leisure Sci. 34, 19–38 (2012).

Feneberg, A. C. et al. Perceptions of stress and mood associated with listening to music in daily life during the COVID-19 lockdown. JAMA Netw. Open. 6, e2250382 (2023).

Billboard. Billboard https://www.billboard.com/

Federal Reserve Economic Data. | FRED | St. Louis Fed. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

Richardson, L. Beautiful Soup Documentation. (2007). https://beautiful-soup-4.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

lyrics.ovh. Only the lyrics. https://lyrics.ovh/

Genius, A. P. I. & Documentation https://docs.genius.com

Papia, S. K., Khan, M. A., Habib, T., Rahman, M. & Islam, M. N. DistilRoBiLSTMFuse: an efficient hybrid deep learning approach for sentiment analysis. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 10, e2349 (2024).

Boyd, R., Ashokkumar, A., Seraj, S. & Pennebaker, J. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22. (2022).

Hutto, C. & Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious Rule-Based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. Proc. Int. AAAI Conf. Web Social Media. 8, 216–225 (2014).

Al-Shabi, M. Evaluating the performance of the most important Lexicons used to Sentiment analysis and opinions Mining. (2020).

Youvan, D. Understanding Sentiment Analysis with VADER: A Comprehensive Overview and Application. (2024).

Allaith, A. et al. Sentiment Classification of Historical Danish and Norwegian Literary Texts. In Proceedings of the 24th Nordic Conference on Computational Linguistics (NoDaLiDa) (eds Alumäe, T. & Fishel, M.) 324–334 (2023).

Rebora, S. Sentiment analysis in literary studies. a critical survey. Digital Humanit. Quarterly 17, 1–17 (2023).

Ziv, J. & Lempel, A. A universal algorithm for sequential data compression. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory. 23, 337–343 (1977).

Gailly, J. & Adler, M. (2004). zlib compression library.

Newey, W. K., West, K. D. A. & Simple Positive Semi-Definite, heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix. Econometrica 55, 703–708 (1987).

Turner, S. L. et al. Design characteristics and statistical methods used in interrupted time series studies evaluating public health interventions: a review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 122, 1–11 (2020).

Zhang, F., Wagner, A. K. & Ross-Degnan, D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 64, 1252–1261 (2011).

Durbin, J. & Watson, G. S. Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression: I. Biometrika 37, 409–428 (1950).

Ljung, G. M. & Box, G. E. P. On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika 65, 297–303 (1978).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals Stat. 6, 461–464 (1978).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in python. Nat. Methods. 17, 261–272 (2020).

Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Econometric and statistical modeling with python. in 9th Python in Science Conference (2010).

Vallat, R. Pingouin: statistics in python. J. Open. Source Softw. 3, 1026 (2018).

Hyndman, R. J. & Khandakar, Y. Automatic time series forecasting: the forecast package for R. J. Stat. Softw. 27, 1–22 (2008).

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna. M.M. also received funding from the European Union under the grant agreement Nº 101094988, CRESCINE - Increasing the international competitiveness of the film industry in small European markets (HORIZON-CL2-2022-HERITAGE-01). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the European Research Executive Agency can be held responsible for them. The authors thank Tudor Popescu for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foramitti, M., Nater, U.M., Lamm, C. et al. Societal crises disrupt long-term increases in stress, negativity, and simplicity in US Billboard song lyrics from 1973 to 2023. Sci Rep 15, 41733 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28327-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28327-5