Introduction

Few technological breakthroughs have penetrated as deeply across different applications as the laser1,2. Many classes of traditional, quasi-one-dimensional, mirrored cavity lasers exist such as the gas laser, liquid dye laser, solid state laser, chemical laser, and semiconductor laser3. Laser emission can also be found in many nontraditional architectures including distributed Bragg reflector lasers4,5,6, distributed feedback lasers7,8,9, random lasers10,11,12,13,14,15,16, and whispering gallery mode lasers17,18.

There has in recent years been a notable increase in the intensity of biolasers research. When biological material is introduced into a gain region, small changes in the material can be determined19,20. Biolasers can contain a single cell as the gain medium21,22 or entire tissue samples23,24,25. The feedback structure does not need to be an external cavity, where colloidal droplets were shown to create whispering gallery mode lasers26,27. Biolasing has also been demonstrated by embedding a nanocavity with periodically spaced holes inside a single cell28. The feedback mechanism in a biolaser does not necessarily need to be externally introduced; biological photonic structures can also affect light generated within them. Random laser emission has been observed from stained bovine bones29, blue coral skeletons30, insect wings31,32, sandwiched parrot feathers33, and human tissue34. Similarly, reduced threshold amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) was observed to be emitted from the one-dimensional aperiodic photonic structures in salmon iridophores35. We initially hypothesized that the dispersive structural color found in the periodic photonic crystals of some biological materials can be used as the feedback mechanism for non-random laser emission.

In contrast to device applications, characterization of the laser light emitted from a material doped with gain molecules can provide information about the microstructure of the material. There is a plethora of structural color in the animal kingdom36,37,38,39. The feathers from many species of birds have a variety of different light-interfering structures40,41,42,43,44. Here, we investigate laser emission from male peafowl (Pavo cristatus) tail feathers45,46,47,48,49,50 infused with the laser dye, rhodamine 6g (R6g). The system is found to emit laser light that cannot be random laser emission; however, the feedback for the laser emission is also not found to be caused by the color region-specific photonic crystal structure of the eyespot. A set of laser modes is presented that are found through all parts of the eyespot and in different feathers, where the feedback mechanism responsible is attributed to small mesoscale structures.

Methods

Feather preparation

The peafowl feathers used in this study were sourced from the company Piokio via the US-based online retailer, Amazon. Peafowl feathers are a common decorative product, and like many art-related products, the feathers can be stained with various dyes for esthetic reasons. All feathers in this study were inspected before experimentation and contain no impurities from vendor post-processing. For reproducibility purposes, it is important for researchers to source unadulterated feathers, often described as “natural.” After inspection, the rachis was severed below the eyespot. All excess lengths of barbs were also cut away, and the feather sample was then mounted on an absorptive substrate. To confirm that the absorptive substrate did not contribute to the emission peaks, emission spectra from a free-standing feather were recorded (see Fig. S5 in the supplementary document).

Reflection spectra

Reflection spectra were recorded over the different color regions at normal incidence. Light from a Haraqi, \(12\,\)V, \(50\,\)W, halogen bulb illuminated six fibers in a hexagonal pattern surrounding a central fiber (each \(200\,\upmu\)m in diameter). Light reflected from the sample entering the center fiber was analyzed by an Ocean Optics USB4000 spectrometer. White paper was used as the diffuse reflector reference material. All reflection spectra recorded from the eyespot regions were referenced to a single source spectrum from a \(\sim 1\,\)mm diameter spot on the white-paper reference. Care was taken to maintain the integrity of the source spectrum magnitude during the reflection spectra recordings for the reference and eyespot regions by maintaining a constant temperature of the halogen bulb via an aluminum chamber surrounded by an ice water bath. All spectra were recorded after temperature-dependent transient behavior of the source decayed.

Microscope imaging

Images of the various color regions were captured through two different microscope systems. Low magnification images were collected by a Celestron eyepiece camera connected to a dissection microscope. A Canon EOS 6D Mark II camera was mounted on an Olympus BH-2 fluorescence microscope to take high magnification images. The mercury lamp attached to the BH-2 was replaced with an Osram, \(24\,\)V, \(150\,\)W halogen bulb with a separate power supply, and a 50/50 beam splitter cube was inserted to take the bright-field images.

Infusion of laser dye

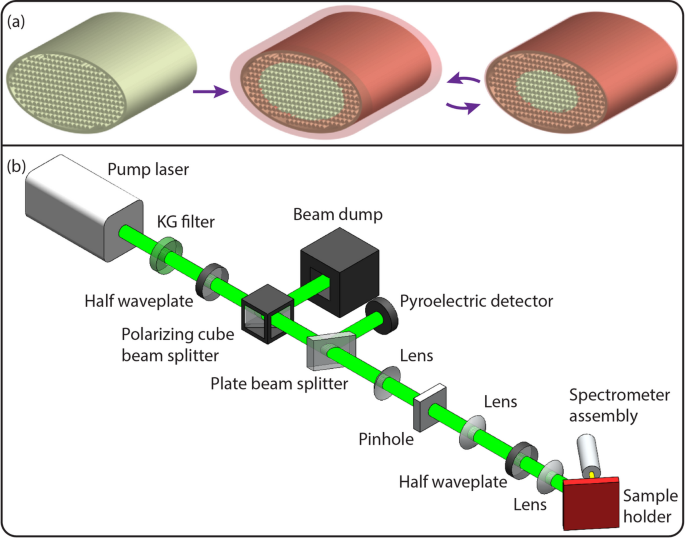

Dye solutions were made by dissolving R6g in a solvent at a mass/volume ratio of \(12\,\)g/L. A 70% ethanol, 30% deionized water, volume/volume ratio was used as the solvent. Fluorescence spectra at different pump pulse energies for the dye solution are shown in Fig. S4 of the supplementary document. The feathers were stained by pipetting the dye-doped solution onto the feather and allowed to dry. This process was repeated on the same specimen several times as shown in the illustration of Fig. 1a. Images of dried, dye-infused feathers are shown in Fig. S6 of the supplementary document.

Experimental setup

Peafowl tail feathers were infused with fluorescent dye as described in “Infusion of laser dye” and shown in Fig. 1a. The setup shown in Fig. 1b performed the emission measurements. The pump laser was a frequency doubled Nd:YAG operating at \(532\,\)nm at a \(10\,\)Hz repetition rate with a pulse duration of \(~10\,\)ns. An oscilloscope trace of the pulse taken from a fast photodiode is shown in Fig. S3 of the supplementary document. The beam was immediately passed through KG-1 Schott glass to remove any residual \(1064\,\)nm light. Beam power was adjusted by rotating the polarization with a \(\lambda /2\) waveplate and passing the beam through a polarizing beam splitter. The pulse energy was tracked by separating a small fraction of the beam and directing it onto a pyroelectric reference detector, Ophir PE9-ES-C. The beam was then focused through a \(400\,\upmu\)m pinhole and collimated on the other end. A lens, with identical focal length to the second collimating lens, focused the pump beam onto the sample. Light emerging from the sample passed through a \(550\,\)nm longpass filter and was conducted into a \(300\,\upmu\)m multimode fiber terminated by an Optics HR4000 spectrometer. The pump power was monitored by the reference detector collecting absolute power measurements. The pump power at the samples location was determined with a calibration factor which translates the reference detector power to the pump’s pulse energy incident on the sample.

(a) Illustration of a barbule’s cross section which is repeatedly stained with a dye solution. (b) Experimental setup for detecting emission from a male Indian peafowl tail feather stained with R6g.

Results

Reflectance

The barbules of a male peafowl tail feather are composed of melanin rods coated in keratin. As shown by Han et al.45 the keratin sheath contains long strands of ordered rods that result in colorful iridescence. The keratin sheath is very thin, where wavy surface formations appear on the surface of the barbule as shown in S1 of the supplementary document. The contribution of the wavy formations in the sheath to the reflection spectrum is expected to be negligible; they are also not expected to contribute to the laser emission reported in this study.

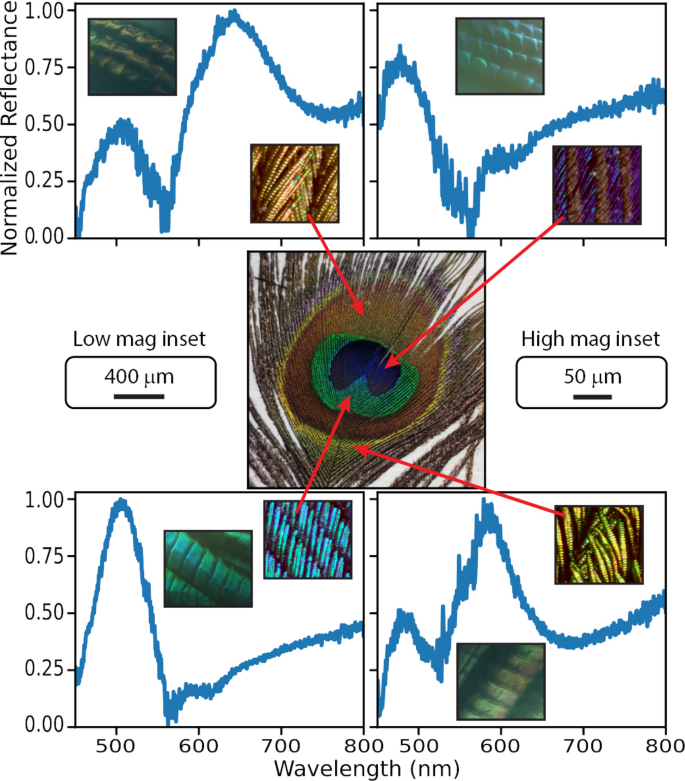

The reflection bands from the different color regions of the peafowl tail feather’s eyespot are shown in Fig. 2. Only a few bands are necessary to create the observed colors, where bands are located in the blue spectrum, the green spectrum, the orange/yellow spectrum, and the red spectrum. There is one very large reflection band which results in green iridescence as shown in Fig. 2c. The brown region, Fig. 2a, shows a combination of structural color bands, where a large and broad red reflection band is observed in relation to the less reflective and narrower green band. The yellow region has a hint of green iridescence as observed in the images shown in Fig. 2d as well as the two narrow reflection bands in the green and the yellow/orange region of the visible spectrum. A reflection band, similar in width to the green band, appears in the blue iridescent region of the eyespot as shown in Fig. 2b. This blue or green band responsible for the iridescence does appear in all color regions; however, it is moderately shifted between the color regions.

Image of a peafowl tail feather’s eyespot surrounded by reflection spectra for four distinct color regions. Each spectra has two insets, a low-magnification and a high-magnification microscope image of that color region.

Each color region of a peafowl tail feather’s eyespot looks rather monolithic when viewed without a microscope; however, the low-magnification microscope images, the insets of Fig. 2, show heterogeneities. The brown region is particularly interesting, where the ends of some barbules appear to have a brilliant green or yellow sheen. High-magnification microscope images are also shown as insets in Fig. 2. These high-magnification images tell another interesting story, where the keratin sheath for barbules in the green iridescent region are smooth relative to the sheaths of the brown-colored parts of barbules. Another set of microscope images is also shown in Fig. S2 in the supplementary document. The scale of the high-magnification microscope can be approximated by comparing the same features shown in the insets of Fig. 2 with the SEM images shown at the top of Fig. S1.

Regional sampling of emission

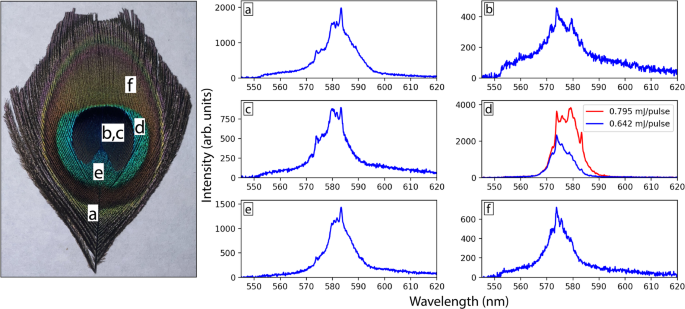

There were no signs of laser emission from any part of the feather when only staining once with R6g in 70% ethanol. The sharp peaks shown in the plots of Fig. 3 were only observed after following a procedure of multiple wetting and complete drying cycles, and then pumping while the feather was still wet during the final cycle. The stain cycling indicates the diffusion of both dye and solvent into the barbule. The cycling also indicates loosening of the fibrils in the keratin sheath which has previously been reported for the soft keratin of mammalian corneocytes with lower concentrations of ethanol51.

We observed sharp peaks in emission spectra for all color regions of the feather’s eyespot. These peaks, like the ones shown in Fig. 3, appeared prior to reaching the burn threshold of the biological material. The green region resulted in the strongest emission profile as shown in Fig. 3. The sharp peaks in the emission profiles were observed to depend on the pump intensity. Broadening of the fluorescence spectrum via a red shift in the long-wavelength edge also occurred at higher pump intensities. This pump dependence is illustrated in Fig. 3 for the green iridescent region (location d).

The absorption band of R6g is maximum in the green part of the visible spectrum. The fluorescence of R6g is in the yellow/orange parts of the spectrum. We would only expect laser emission to be produced in a physical volume with a gain profile that does not overlap with the absorption spectrum. A strong emission peak at \(583\,\)nm was observed as shown by spectrum (e) in Fig. 3, which is close to the fluorescence maximum of the dye. A small emission peak at \(574\,\)nm, closer to the absorption band of R6g, was also observed in the emission spectrum.

Analysis of laser emission spectrum

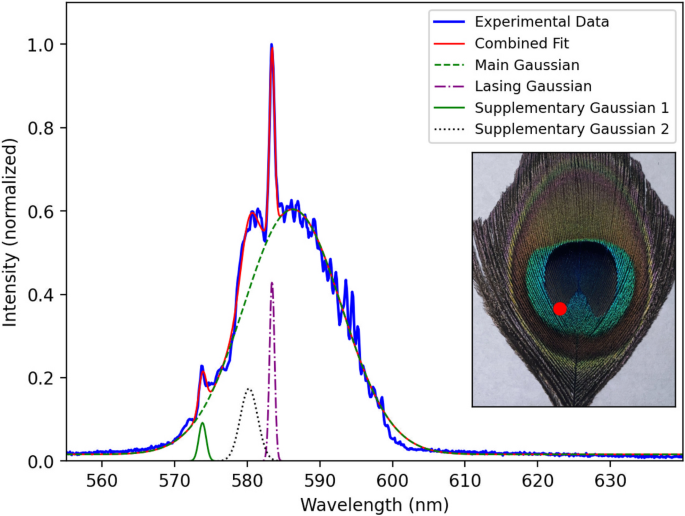

A more prominent emission line, which was taken while pumping the green color region of the peafowl tail feather, is shown in Fig. 4. The spectrum shows a dominant peak relative to the other much smaller peaks, which indicates a dominant lasing mode. A N-peak Gaussian fit was used to characterize the emission peaks whose width and growth with power was used to separate them from the fluorescence and ASE. The multipeak Gaussian was of the form

$$\begin{aligned} \frac{I\left( E\right) }{I_\textrm{max}} = B + \sum _{i=1}^N \frac{A_i}{\sqrt{2\pi \sigma _i}} e^{-\left( E - E_i\right) ^2/2\sigma ^2} \,. \end{aligned}$$

(1)

where the ith peak’s parameters are defined as \(A_i\) being the area, \(E_i\) denoting the resonant energy, and \(\sigma _i\) corresponding to the standard deviation of the Gaussian.

Emission spectrum observed while pumping the iridescent blue region of the tail feather. A 4-peak Gaussian fit was used to model the emission spectrum.

For simplicity only a 4-peak Gaussian fit is shown in Fig. 4. Only two Gaussian peak functions are needed to describe the fluorescence (Main Gaussian) and ASE (Supplementary Gaussian 2) within a reasonable degree of accuracy. The long-wavelength edge is not well-fit by the large Gaussian in the 4-peak Gaussian fit. The small peak at \(\sim 574\,\)nm (Supplementary Gaussian 1) and the large peak at \(\sim 583\,\)nm (Lasing Gaussian) are fit by the remaining two peak functions. There are other small “hidden” peaks in the profile, but additional Gaussian functions are required to include those broader peaks.

The spectrum shown in Fig. 4 is emitted after pumping with an energy density of \(\sim 5\,\)mJ/mm\(^2\) and \(10\,\)ns pulse duration. At such intensities, we initially considered a random lasing phenomenon as the possible mechanism, but such an explanation seems unlikely after observing the same modes emitted from other locations on the feather’s eyespot. Similar emission peaks where observed within the gain profile of R6g across different color regions of the feather’s eyespot. For example, Fig. 3 shows the \(583\,\)nm line emitted from the blue/violet, green, and yellow regions. There appears to be a persistent structure in all parts of the color regions that contribute to the locations of emission lines, which is not consistent with laser emission from a random media of scattering particles.

Laser emission comparison

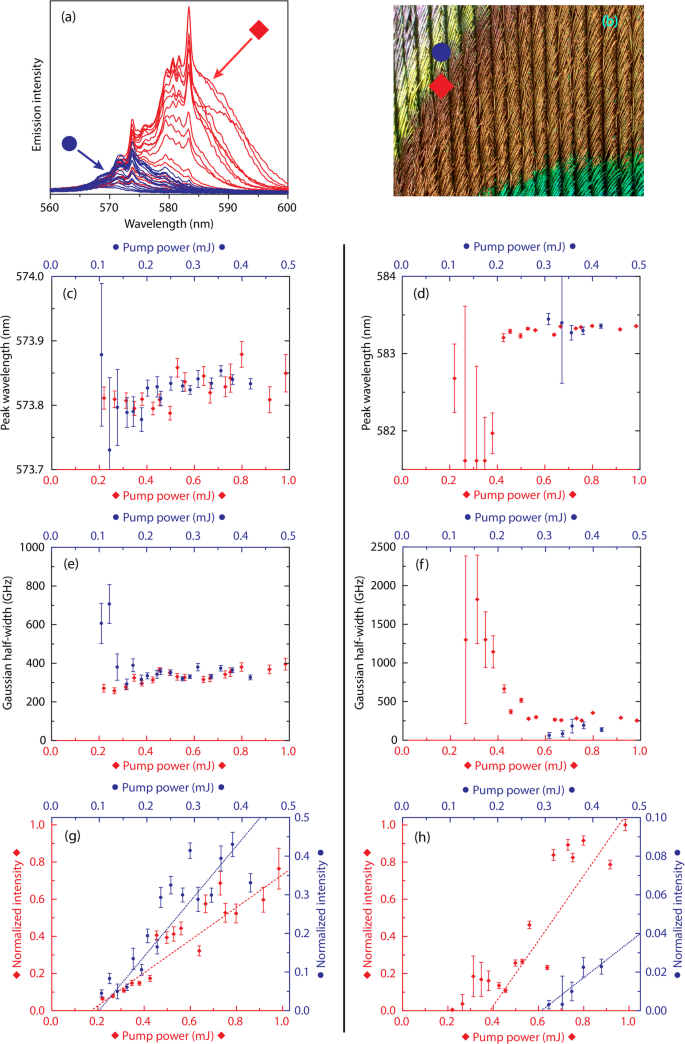

The (a) emission spectra as a function of pump intensity taken from (b) the yellow (blue disk) and brown (red diamond) color regions of a male Indian peafowl tail feather. (c) The emission line at \(\sim 574\,\)nm for both regions along with (e) the Gaussian half-width and (g) the scaled output intensity. (d) The emission line at \(\sim 583\,\)nm for both regions along with (f) the Gaussian half-width and (h) the scaled output intensity.

Laser emission was detected from the yellow and brown color regions shown in Fig. 5b. The emission spectra from both regions for different pump pulse energies are shown in Fig. 5a. A 7-peak Gaussian fit was used to increase the accuracy of the reconstructed spectra, where the parameters (peak wavelength, Gaussian half-width, and intensity) are given in Fig. 5c–h. The fit uncertainties shown in the plots were calculated from the covariant matrix and are not associated with all experimental uncertainties.

A transition to laser emission can be observed in both color regions. The two narrow lines that overlap are at \(574\,\)nm and \(583\,\)nm. The brown region showed a line quickly emerge at \(574\,\)nm, where we were unable to record the pump power for the below-threshold behavior due to the reference detector being unable to record the power of the weak reference beam that was split just after the power adjusting optics (see optical setup in Fig. 1). The peak emitted from the brown region with a higher slope efficiency was centered around \(583\,\)nm. Line width narrowing, similar to Schawlow-Townes narrowing (inversely proportional to the laser emission power), is observed near its threshold as shown in Fig. 5f,h. The low slope efficiency line emitted from the yellow region was at \(583\,\)nm, where the small peak immediately formed. Parameters at weak pump pulses are not shown because they correlate to the broad spectrum as opposed to the localized spectral region. The stronger line emitted from the yellow region at \(574\,\)nm also shows narrowing of laser emission through observation of the Gaussian half-width as a function of pump power shown in Fig. 5e.

The absolute power emitted by the sample was not collected by the fiber spectrometer. The normalized intensity values were referenced to the largest value recorded, which was the \(583\,\)nm line emitted from the brown color region at the maximum pump intensity. Because the power measurements are on a normalized scale, the slope efficiencies should also be relative, where we define the relative slope efficiency by

$$\begin{aligned} S_{\mathrm {wavelength\,\,in\,\,nm}}^{\textrm{region}} = \frac{\mathrm {slope\,\,from \,\,region \,\,at \,\, wavelength}}{\mathrm {slope \,\,from \,\,brown \,\,region \,\,at\,\,}583\,\textrm{nm}} \, , \end{aligned}$$

(2)

and the relative slope efficiencies follow as \(S_{574}^{\textrm{brown}} = 0.50\pm 0.11\), \(S_{574}^{\textrm{yellow}} = 0.84\pm 0.20\), and \(S_{583}^{\textrm{yellow}} = 0.11\pm 0.03\). Note that much of the uncertainty associated with the relative slope efficiency values was sourced from the propagation of uncertainty in the \(583\,\)nm line’s slope efficiency for the brown color region, which was 19%. Setting \(S_{583}^{\textrm{brown}} = 1\) for the normalization scheme required the propagation of uncertainty to the relative slope efficiency for the other three cases.

The largest slope efficiency for the brown region was obtained for the \(583\,\)nm line while the largest slope efficiency for the yellow region was from the \(574\,\)nm line. These results are well understood by assessing the gain envelope from the spectra in Fig. 5a. The \(583\,\)nm and \(574\,\)nm peaks are near the center’s of the fluorescence bands emitted from the respective brown and yellow color regions. The relative slope efficiency of the \(583\,\)nm line emitted from the yellow color region showed little growth after it appeared relative to the growth of the broad emission spectrum.

The slit-dependent resolution of the HR4000 spectrometer was \(\sim 0.13\) nm in the spectral region associated with laser emission. The Gaussian fits can slightly increase the measured precision of the peak wavelength of laser emission; however, spectrometer noise reduces the accuracy. The general trend in Fig. 5c,d above the lasing threshold shows a slight redshift of the peak laser wavelength when the pump energy is increased.

The pump beam spot size was \(A \sim 0.2\,\)mm\(^2\). Dividing the x-intercept from the linear regression fits by the pump spot size results in threshold estimates of the laser lines emitted from each color region. The thresholds for the \(574\,\)nm line were \(\sim 170\,\upmu\)J/mm\(^2\) and \(\sim 100\,\upmu\)J/mm\(^2\) for the respective brown and yellow color regions. The thresholds for the \(583\,\)nm peak were found to be \(\sim 380\,\upmu\)J/mm\(^2\) for the brown region and \(\sim 290\,\upmu\)J/mm\(^2\) for the yellow color region of the feather’s eyespot. Because the pump pulse is \(\sim 10\,\)ns, dividing the threshold values in \(\upmu\)J/mm\(^2\) by 100 converts them to fluence in units of MW/cm\(^2\). These threshold values are associated with laser emission that cannot be classified as random; however, the thresholds are comparable to some random lasers. The thresholds observed from these experiments are similar to random lasers involving TiO\(_2\) nanoparticles reported by Lawandy et al.10. The thresholds are much lower than the non-resonant feedback random laser experiments using ZrO\(_2\) nanoparticles reported by Anderson et al.15. The thresholds are higher than the ultraviolet random laser values in polycrystalline zinc oxide reported by Cao et al.52.

Discussion

This study began with the intent to study laser emission from the feedback caused by the same structures that give the Indian peafowl tail feather its color. Using the infusion technique described in “Infusion of laser dye” and the experimental setup described in “Experimental setup”, evidence of laser emission was obtained. The emission characteristics did not support the hypothesis that the structures responsible for the iridescent colors in the eyespot were associated with the laser feedback mechanism.

The key experimental findings presented in this article and supplementary document follow:

-

1.

Line narrowing is observed for the emission lines.

-

2.

The power dependence of multiple emission lines show different thresholds and slope efficiencies.

-

3.

Emission lines at the same frequencies are observed across all color regions of the eyespot and in different feathers.

-

4.

The reflection spectra of different eyespot color regions exhibit relatively low dispersion at the reflection band edges.

Experimental findings 1 and 2 from the enumerated list confirm that the peaks shown in the recorded spectra were indeed laser emission lines. The line narrowing from finding 1 only confirms the amplification of emission, where amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) also exhibits line narrowing, albeit a much broader line is typically associated with ASE from a laser dye solution. The power dependence of a single peak relative to the background fluorescence in finding 2 could also be associated with ASE or laser emission. There are multiple emission lines with different thresholds and slope efficiencies, however, which confirms multimode laser emission.

The thresholds are relatively high and on the order of random laser thresholds. Random lasers assume that feedback is formed from the resonance associated with scattering paths, where the laser lines are randomly distributed over the gain profile and the modes will shift with a high sensitivity to experimental conditions. Experimental finding 3 indicates a very stable system that produced laser emission at specific wavelengths. The consistency of the emission wavelength over which these spectral peaks were observed across multiple feathers confirms that the emission is not from random laser modes. The persistent laser modes were also independently confirmed through an undergraduate laboratory class assignment, where the students followed the preparation instructions from a shared preprint of this article using different feather samples (see Fig. S7 in the supplementary document).

Experimental finding 4 confirms low dispersion at the edges of the reflection bands observed in different color regions. Because high dispersion, \(dn/d\lambda\), results in low photon group velocity at those wavelengths, laser emission is most probable in systems with high dispersion locations in the spectrum such as sharp band edges and sharp Airy modes in traditional laser cavities. Because low dispersion was observed in the reflection spectra of all color regions, if any laser emission was caused by the structures that cause the perceived eyespot colors, the laser thresholds would be high. The consistency of laser emission wavelengths across different feathers from experimental finding 3 and the heterogeneity of the feathers’ structure, which contributes to the low dispersion of the band edges from finding 4, makes laser emission from long-range feedback in the bands highly unlikely. Furthermore, there is also a heterogeneity contribution to the low dispersion band edges from the collection of spectra over a physical area. For uncoupled laser modes emitted by a material with a heterogeneous envelope of periodic structures, the resultant emission lines would appear much broader than those recorded in this study.

All experimental findings point towards highly regular structures that persist through all color regions. The high thresholds indicate many tiny structures with small gain volumes that independently emit laser radiation at the same wavelengths. We hypothesize that these structures are akin to mesoscale building blocks within the feather eyespot that cause the feedback mechanism responsible for laser emission after wet/dry cycling the barbules during the dye-infusion process. Note that although these laser modes are not attributed to random laser emission, we did observe random laser light when increasing the pump energy beyond the sample burn threshold. Additional dye/solvent was added to the sample to avoid burning, but the superheated fluid vaporized and quickly coated the long-pass filter with dye. Spectra showing the two lower-threshold laser modes (at \(574\,\)nm and \(583\,\)nm) as well as some random laser modes are given in Fig. S8 of the supplementary document.

Although we have discussed the unlikelihood of the two consistent laser modes being attributed to feedback from random modes in a medium with scatterers, we offer one last insight to help guide the reader, and possibly create a new addition to your next physics game night. Consider a random laser made from a collection of randomly distributed scatters embedded in an otherwise homogeneous and isotropic gain medium. The scattering pathways that result in feedback is assumed to follow a flat distribution. The probability for the first random laser mode occurring between any two wavelengths are related to the gain profile. Suppose we made a game that can be wagered upon from such a random laser system; a gambler must pick from a number of wavelength regions (e.g., \(1\,\)nm-wide bins) over which the first random laser mode will appear while the input power delivered to the gain material is increased. Because the gain profile is not flat in real systems, the payout must follow a probability distribution associated with the gain profile. Now, if a casino were to pick up this game, then they would choose a true resonant-feedback random laser with the described properties. The casino would most definitely avoid our system which consistently produces two laser modes before any random laser modes appear. The system presented in this article is akin to a roulette table in which the ball always lands in either red 7 or black 28. On that table, the inside betting gambler is transformed in a savvy investor while the house quickly goes out of business.

There are several possible routes to the observed laser emission that produce a set of consistent peak wavelengths based on rather small resonators. It seems unlikely that whispering gallery mode (WGM) laser operation would be supported in the feather. If the coherent emission was from a whispering gallery mode (WGM) laser, then the radius of the object can be estimated from the free spectral range, \(\textrm{FSR} \sim 9\,\)nm. For a disk resonator, the radius of the disk would be given by \(r = \lambda ^2/2\pi n \left( \textrm{FSR}\right) \sim 3.8\,\upmu\)m53, where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength and a constant refractive index for keratin, \(n\approx 1.56\), based on the human hair54. Likewise, a spherical resonator would have radius of \(\sim 3.8\,\upmu\)m. These geometries do not appear naturally in the peafowl feathers and it is unlikely that such geometries form with such consistency through the dye-infusion process. Therefore, we conclude that the observed laser emission is not caused by WGM lasers.

The difference between the solution and keratin refractive index is significant, \(\Delta n \approx 0.2\). It is unlikely that multiple keratin/solvent layers form to produce precise emission modes; however, single configurations of keratin that are surrounded by dye-doped solvent could result in cavity resonances. If the two laser modes are independent, then there are at least two structures with a well-defined length after processing the material during the dye-infusion process. The optical length of the cavity follows from the interference condition that results in the largest feedback, \(\left( m+1/2\right) \lambda = nL\), where \(m = 0,1,2,\ldots\). Assuming \(n\approx 1.56\), the long wavelength mode has a cavity with m possible characteristic lengths, \(L_{583\,\textrm{nm}} \approx \left( m+1/2\right) \,\left( 374\,\textrm{nm}\right)\). The short wavelength mode has a cavity length of \(L_{574\,\textrm{nm}} \approx \left( m+1/2\right) \,\left( 368\,\textrm{nm}\right)\). The smallest length occurs when \(m=0\), which have cavity lengths of \(L_{583\,\textrm{nm}}^\textrm{shortest} \approx 93\,\textrm{nm}\) and \(L_{574\,\textrm{nm}}^\textrm{shortest} \approx 92\,\textrm{nm}\). In addition to the possibility of two different cavity lengths, they might also be associated with the two band edges for a reflection band of finite width from a few keratin strands. The birefringence of keratin could also cause the same physical length to support both modes. The two supported modes are around 1.5% different; however, experiments on bulk keratin from human hair show a smaller birefringence;54 however, the microscopic structure might have greater birefringence than an imperfectly ordered bulk material. It is also possible that keratin strands act as a scaffold for crystalline R6g to adhere which would form regular structures with a higher refractive index than keratin. These crystalline dye cavities would require a smaller cavity length than the proposed keratin cavities over the observed laser emission wavelengths. Finally, the two modes could be supported in the same cavity. In such a case, the FSR suggests that the cavity length formed from keratin is about \(24\,\upmu\)m. It may be unlikely, but still possible that structures at these length scales are building blocks that have precise lengths and consistently found through all eyespot color regions and across multiple samples.

Conclusion

The eyespot of a dye-doped peafowl tail feather was found to emit laser light from multiple structural color regions. Regions where the visible reflection bands were outside of the gain region of the dye were also found to emit laser light in some locations. The greatest laser intensity relative to the broad emission curve was found to be emitted from the green color region. The same laser line at \(583\,\)nm was also observed to emitted from areas in the brown and yellow color region. The laser lines emitted from the brown and yellow regions were characterized, where it was shown that the brown region had a larger slope efficiency, but also a greater threshold as compared to the \(583\,\)nm laser peak.

The feather was found to require multiple staining cycles before laser emission was observed which indicates that diffusion of the laser dye into the feather was required along with possible loosening of the keratin fibrils for the observed effects. Similarities between the laser emission peaks generated in different color regions indicate regular mesoscale structures that appear through much of the feather’s eyespot, including regions with structural color differences. The method presented in this article illustrates how measuring the emission spectrum from a biological sample processed with solvent/dye cycling at pump intensities above the laser threshold can be used to determine resonances associated with regular “hidden” structures in complex biological media.

Data availability

The data presented in this article is provided in graphical format. Emission spectrum data shown in Fig. 5 can be found at https://doi.org/10.17632/mp9j46pgg2.1. All other inquiries for .npy and ASCII formatted data used to generate the graphs can be requested from N.J.D. at ndawson@floridapoly.edu.

References

Schawlow, A. L. & Townes, C. H. Infrared and optical masers. Phys. Rev. 112, 1940–1949. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.112.1940 (1958).

Maiman, T. H. Stimulated optical radiation in ruby. Nature (London) 187(4736), 493–494 (1960).

Paschotta, R. Field guide to lasers (SPIE Press, Bellingham, Wash, 2008).

Singer, K. D. et al. Melt-processed all-polymer distributed Bragg reflector laser. Opt. Express 16(14), 10358–10363 (2008).

Andrews, J. H. et al. Thermo-spectral study of all-polymer multilayer lasers. Opt. Mater. Express 3(8), 1152–1160 (2013).

Canazza, G. et al. Lasing from all-polymer microcavities. Laser Phys. Lett. 11(3), 035804 (2014).

Komikado, T., Yoshida, S. & Umegaki, S. Surface-emitting distributed-feedback dye laser of a polymeric multilayer fabricated by spin coating. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89(6), 061123 (2006).

Navarro-Fuster, V. et al. Highly photostable organic distributed feedback laser emitting at 573 nm. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97(17), 171104 (2010).

Retolaza, A. et al. Organic distributed feedback laser for label-free biosensing of ErbB2 protein biomarker. Sensor. Actuat. B 223(C), 261–265 (2016).

Lawandy, N. M., Balachandran, R. M., Gomes, A. & Sauvain, E. Laser action in strongly scattering media. Nature 368(6470), 436 (1994).

Polson, R. C. & Vardeny, Z. V. Random lasing in human tissues. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85(7), 1289–1291 (2004).

Wiersma, D. S. The physics and applications of random lasers. Nat. Phys. 4(5), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys971 (2008).

Zaitsev, O. & Deych, L. Recent developments in the theory of multimode random lasers. J. Opt. 12(2), 024001 (2010).

Sznitko, L., Mysliwiec, J. & Miniewicz, A. The role of polymers in random lasing. J. Polym. Sci. B: Polym. Phys. 53(14), 951–974. https://doi.org/10.1002/polb.23731 (2015).

Anderson, B. R., Gunawidjaja, R. & Eilers, H. Random lasing and reversible photodegradation in disperse orange 11 dye-doped pmma with dispersed ZrO\(_2\) nanoparticles. J. Opt. 18, 015403 (2016).

Chou, C.-J. et al. Realizing a flexible and wavelength-tunable random laser inspired by cicada wings. J. Mater. Chem. C 12, 5701–5707. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3TC03576J (2024).

Kuwata-Gonokami, M. & Takeda, K. Polymer whispering gallery mode lasers. Opt. Mater. 9(1), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-3467(97)00160-2 (1998).

Wei, G.-Q., Wang, X.-D. & Liao, L.-S. Recent advances in organic whispering-gallery mode lasers. Laser Photonics Rev. 14(11), 2000257. https://doi.org/10.1002/lpor.202000257 (2020).

Fan, X. & Yun, S.-H. The potential of optofluidic biolasers. Nat. Methods 11(2), 141–147 (2014).

Gong, X., Feng, S., Qiao, Z. & Chen, Y.-C. Imaging-based optofluidic biolaser array encapsulated with dynamic living organisms. Anal. Chem. 93(14), 5823–5830. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c00020 (2021).

Gather, M. & Yun, S. Single-cell biological lasers. Nature Photon. 5, 406–412 (2011).

Prasetyanto, E. A., Wasisto, H. S. & Septiadi, D. Cellular lasers for cell imaging and biosensing. Acta Biomater. 143, 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actbio.2022.03.031 (2022).

Chen, Y.-C., Chen, Q., Zhang, T., Wang, W. & Fan, X. Versatile tissue lasers based on high-Q Fabry-Pérot microcavities. Lab. Chip 17(3), 538–548 (2017).

Chen, Y.-C. et al. A robust tissue laser platform for analysis of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies. Lab. Chip 18, 1057–1065. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8LC00084K (2018).

Chen, Y.-C. & Fan, X. Biological lasers for biomedical applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7(17), 1900377. https://doi.org/10.1002/adom.201900377 (2019).

Humar, M. & Yun, S. H. Intracellular microlasers. Nature photon. 9(9), 572–576 (2015).

Mai, H. H. et al. Chicken albumen-based whispering gallery mode microlasers. Soft Matter 16, 9069–9073. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0SM01091J (2020).

Shambat, G. et al. Single-cell photonic nanocavity probes. Nano Lett. 13(11), 4999–5005 (2013).

Song, Q. et al. Random lasing in bone tissue. Opt. Lett. 35(9), 1425–1427. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.35.001425 (2010).

Lin, W.-J. et al. All-marine based random lasers. Org. Electron. 62, 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgel.2018.07.028 (2018).

Wang, C.-S., Chang, T.-Y., Lin, T.-Y. & Chen, Y.-F. Biologically inspired flexible quasi-single-mode random laser: An integration of pieris canidia butterfly wing and semiconductors. Sci. Rep. 4(1), 6736. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06736 (2014).

Chen, S.-W. et al. Random lasers from photonic crystal wings of butterfly and moth for speckle-free imaging. Opt. Express 29(2), 2065–2076. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.414334 (2021).

Chen, S.-W. et al. Study of laser actions by bird’s feathers with photonic crystals. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 2430–2430 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Random lasing in human tissues embedded with organic dyes for cancer diagnosis. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 8385–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08625-3 (2017).

Dawson, N. J. & Lynch-Holm, V. Reduced ase threshold from aperiodic photonic structures in rhodamine b-doped king salmon (oncorhynchus tshawytscha) iridophores. J. Lumin. 241, 118474 (2022).

Berthier, S. Iridescences : the physical colors of insects (Springer, New York, N.Y, 2007).

Sun, J., Bhushan, B. & Tong, J. Structural coloration in nature. RSC Adv. 3, 14862–14889. https://doi.org/10.1039/C3RA41096J (2013).

Kjernsmo, K. et al. Iridescence as camouflage. Curr. Biol. 30(3), 551–5553 (2020).

Sheffield, D. R., Fiorito, A., Liu, H., Crescimanno, M. & Dawson, N. J. Neon tetra fish (Paracheirodon innesi) as farm-to-optical-table bragg reflectors. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 41(11), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAB.532583 (2024).

Yin, H. et al. Iridescence in the neck feathers of domestic pigeons. Phys. Rev. E 74, 051916. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.74.051916 (2006).

Rogalla, S., Patil, A., Dhinojwala, A., Shawkey, M. D. & D’Alba, L. Enhanced photothermal absorption in iridescent feathers. J. R. Soc. Interface 18(181), 20210252. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2021.0252 (2021).

Norden, K. K., Eliason, C. M. & Stoddard, M. C. Evolution of brilliant iridescent feather nanostructures. eLife 10 (2021)

Giraldo, M., Sosa, J. & Stavenga, D. Feather iridescence of Coeligena hummingbird species varies due to differently organized barbs and barbules. Biol. Lett. 17(8), 20210190. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0190 (2021).

Eliason, C. M. et al. Transitions between colour mechanisms affect speciation dynamics and range distributions of birds. Nat. Ecol. Evol. (2024).

Han, J. et al. Embedment of ZnO nanoparticles in the natural photonic crystals within peacock feathers. Nanotechnology 19(36), 365602. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/19/36/365602 (2008).

Pabisch, S., Puchegger, S., Kirchner, H., Weiss, I. M. & Peterlik, H. Keratin homogeneity in the tail feathers of Pavo cristatus and Pavo cristatus mut. Alba. J. Struct. Biol. 172(3), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.003 (2010).

Medina, J. M., Díaz, J. A. & Vukusic, P. Classification of peacock feather reflectance using principal component analysis similarity factors from multispectral imaging data. Opt. Express 23(8), 10198–10212. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.010198 (2015).

Freyer, P. & Stavenga, D. G. Biophotonics of diversely coloured peacock tail feathers. Faraday Discuss. 223, 49–62. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0FD00033G (2020).

Russ, P., Kirchner, H. O. K., Peterlik, H. & Weiss, I. M. Feather keratin in Pavo cristatus: A tentative structure. F1000Research 13(1335). https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.157679.1 (2024).

Sriram, P., Kumari, Y. S. & Kavitha, B. Extraction of keratin from Pavo cristatus (Peacock) feather using HPLC. Flora Fauna 30(2), 282–286 (2024).

Horita, D. et al. Molecular mechanisms of action of different concentrations of ethanol in water on ordered structures of intercellular lipids and soft keratin in the stratum corneum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1848(5), 1196–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.02.008 (2015).

Cao, H. et al. Ultraviolet lasing in resonators formed by scattering in semiconductor polycrystalline films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 73(25), 3656–3658. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.122853 (1998).

Azeem, F., Chaudhry, M. R., Anwar, M. S., Khan, H. A., Ma, L. & A. D. K. Optical whispering gallery mode resonators: analysing thermo-optic tuning in a silicon sphere. J. Roy. Soc. New Zealand 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2024.2395909 (2024).

Hamdoh, A. et al. Polarization properties and Umov effect of human hair. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 412–412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50457-x (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Michael Crescimanno for helpful discussions. The authors thank Professor Virgil Solomon for SEM images and helpful discussions. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation, Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences (Grant No. 2337595).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fiorito, A., Sheffield, D.R., Liu, H. et al. Spectral fingerprint of laser emission from rhodamine 6g infused male Indian Peafowl tail feathers. Sci Rep 15, 20938 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04039-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04039-8