Photovoltaics, being a crucial clean energy source, have experienced rapid development. The establishment and operation of large-scale photovoltaic power stations have significantly contributed to advancing regional socio-economic progress. However, they have altered local surface energy distribution and microclimate, influencing the biogeochemical behavior of biogenic elements within the ecosystem and related material, energy, chemical, and biological domains. This has inevitably impacted ecological hydrological processes, such as soil function regulation, microclimate adjustment, vegetation restoration, and reconstruction1,2,3,4. Therefore, conducting an objective and accurate assessment of the impact of photovoltaic development on the ecological environment holds great importance in ensuring regional ecosystem security and sustainable photovoltaic growth.

Currently, most scholars, both domestic and international, have primarily focused on qualitatively evaluating the ecological and environmental impacts of photovoltaic development. There is a noticeable gap in research regarding the quantitative assessment of the ecological and environmental effects of photovoltaic power stations, leading to the absence of a comprehensive evaluation system. Some researchers have conducted analyses on the environmental repercussions of large solar power plants and waterborne photovoltaic power plants in the United States. Their findings suggest that photovoltaic power generation not only reduces carbon dioxide emissions but also positively influences land use intensity, human health, climate, and hydrology5,6. Moreover, aquatic photovoltaic components have been shown to regulate algae growth in water bodies and maintain water quality7. Overall, the establishment of photovoltaic power stations has contributed to enhancing the ecological environment within the project area.

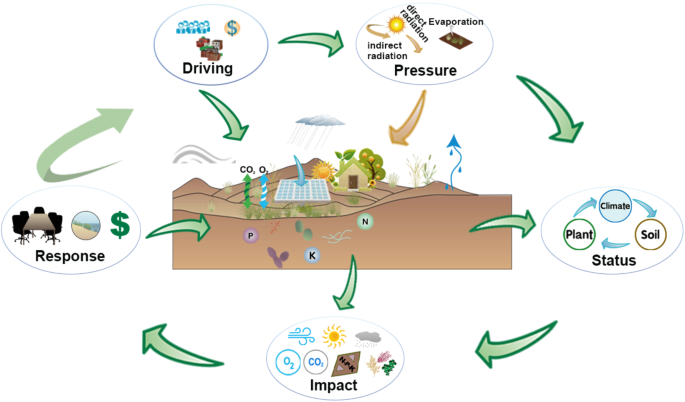

Commonly utilized models for comprehensive ecological evaluations include the Analytic Hierarchy Process, BP neural network model, Grey Cluster Analysis method, and Driving-Force-Pressure-Status-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model. The DPSIR model has been successfully utilized in various environmental assessments, such as evaluating the sustainability of coastal industrial parks8, the impact of surgical masks on the environment9, and the socio-economic dynamics of greenhouse gas emissions10. This model effectively illustrates the causal relationships within a system and incorporates elements such as resources, development, environment, and human health, making it a suitable approach for evaluating watershed ecological security11.

This study focuses on the large-scale photovoltaic industrial park in the desert area of Gonghe County, China. By conducting field research, long-term monitoring, and experimental analysis, evaluation indicators are selected from various aspects including population, economy, society, and natural factors. An ecological environment effect evaluation model based on the DPSIR framework is developed, and the entropy weight method is utilized to determine the weight of the indicators. The study quantitatively evaluates the ecological environment effect of large-scale desert photovoltaic development and analyzes the impact of photovoltaic power station construction on the ecological environment. The findings aim to provide a theoretical basis for the protection and restoration of the ecological environment in desert photovoltaic development zones.

Materials and methods

Study area

In this study, the Qinghai Gonghe Photovoltaic Industrial Park, which is located in Talatan, northeastern Qinghai Province (Fig. 1), at an average altitude of 2910 m, was selected as the investigation site. The study area is characterized by a typical alpine arid desert and semiarid grassland with arid and rainless conditions and uneven rainfall distribution. The average annual temperature, precipitation, evaporation, sunshine duration, total radiation, wind speed, and wind direction are 4.1 ℃, 246.3 mm, 1716.7 mm, 2300–3500 h, 6564.26 MJ/m2, 1.8 m/s, and mainly westerly and northwest, respective12. The soil parent material in the area mainly comprises loess or sandy gravel, with sandy loam and light silty loam textures and sandy gravel and sandy soil as the primary bottom materials13. The area is extensively covered by various annual herbaceous plants, such as Achnatherum splendens, Stipa breviflora, sand fixation grass, Caragana sinica, Leymus chinensis, and Lenghao14. Tara Beach, located in the Gonghe Basin, is the region most affected by salinization and is the main desertification area in the upper part of the Yellow River; it is primarily composed of semifixed and mobile sand dunes15.

The Qinghai Gonghe Photovoltaic Power Park commenced construction in 2012 and was completed in 2015. It employs non-transparent monocrystalline silicon or polycrystalline silicon materials as the core components of the photovoltaic (PV) panels and utilizes three types of installation brackets: fixed, semi-tracking, and tracking. The expected service life of the system is approximately 20 to 30 years. Each bracket of the photovoltaic (PV) system consists of a configuration with an area of approximately 67.40 m². This configuration is composed of 4 rows and 10 columns of PV panels, each measuring 1.65 m in length and 1 m in width, with a spacing of approximately 2 cm between each panel. The lower edges of the PV panels are positioned 0.5 m above the ground, while the upper edges reach 3.03 m above the ground, maintaining a tilt angle of 39° and oriented along a long axis direction of 90°. The overall orientation is due south, with a north-south spacing of 6.87 m and an east-west spacing of 1.55 m. The station consists of 100 strings that form a photovoltaic sub-array, making it currently the largest single photovoltaic power station in the world, with a total installed capacity of 1000 MW.

Geographical location of the Gonghe Photovoltaic Park and distribution of observation points. This map was generated by the authors using ArcGIS 10.8 (http://www.esri.com/software/arcgis) and does not require any license. This study included five mobile meteorological stations (MMSs), three fixed meteorological stations (FMSs), and one carbon flux monitoring station (CFMS) within the solar photovoltaic park (SPP). WPS refers to the built operation area on the site, while TPS denotes the transition area that is to be constructed. OPS represents the off-site original ecological control area, with OPS_SP indicating the sampling point located within this off-site control area; TPS_SP refers to the sampling point situated in the transition area; WPS_FUPP_SP refers to the sampling point located under the semi-tracking bracket within the operational area of the site, WPS_FAPP_SP designates the sampling point located under the fixed bracket within the operational area of the site, WPS_OUPP_SP identifies the sampling point located under the tracking bracket within the operational area of the site. The elevation data of the study area was provided by NASA (https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/search). The images of the research area are provided by Google Earth (https://www.google.cn/intl/zh-CN/earth/).

Data collection and preprocessing

The demographic, economic, and social development data (D1 to D5, D50 to D57 from Fig. 3) for this study were sourced from authoritative reports, including the “Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Hainan Autonomous Prefecture in 2020”, “Work Report of Hainan Autonomous Prefecture Government in 2020”, and “Qinghai Statistical Yearbook 2020”16,17. Due to the relatively small research area, it is difficult to distinguish between on-site, transitional zone, and off-site at the administrative scale. Therefore, this study converted relevant indicators based on the difference in total population inside and outside the photovoltaic field to obtain data inside and outside the field. The data pertaining to vegetation types, species number, and coverage (D8 to D12, D46 and D47, D32 from Fig. 3) were derived from vegetation surveys conducted by the research team in July and September 2020 within the photovoltaic power site, the transition area of the power station, and outside areas of the power station. A total of 12 regions were surveyed in each of the two surveys, resulting in 24 regions overall. In each region, ten 1 m² plots were established at equidistant intervals, from which three plots were randomly selected as survey samples, yielding a total of 36 samples. During the plot establishment process, this study did not evenly distribute the 12 survey areas among WPS, TPS, and OPS; instead, it considered the varying effects of the internal attributes of photovoltaic systems on vegetation. Different types of vegetation were surveyed across three types of photovoltaic arrays (fixed bracket, semi-tracking bracket, and tracking bracket), with two survey areas designated for each type. Additionally, for different positions within the transition zone away from the boundary of the photovoltaic power station, one survey area was established at distances of 200 m, 600 m, and 1500 m, resulting in 6 areas in WPS, 4 in TPS, and 2 in OPS (Fig. 1d). The soil physicochemical data and microbial community characteristics (D13 to D25, D35 to D41, D48 and D49 from Fig. 3) were obtained through four soil sample tests executed between June 2019 and September 2020. Climate data (D6 and D7, D26 and D27, D28 to D31, D42 to D45 from Fig. 3), including temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, and other variables measured every 30 min at a height of 2 m, along with soil temperature, moisture content, and conductivity measured at a depth of 5 cm, were collected from real-time monitoring stations installed in the photovoltaic park between June 2019 and July 2020. Plant oxygen release index (D34) is converted using the photosynthesis formula18,19. For more information on the data sources and collection methods, refer to Table 1.

Construction of an ecological and environmental effect indicator system

Currently, multi-indicator systems are evaluated using comprehensive methods such as principal component analysis, fuzzy comprehensive evaluation, and analytic hierarchy processes20,21. Additionally, the European Environment Agency (EEA) has recommended the Driving-Pressure-Status-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model, which builds on the PSR model, offering better flexibility for ecological security assessments22. This study follows the principles of systematicity, purposefulness, representativeness, scientificity, hierarchy, and measurability and is based on the natural environmental characteristics of Gonghe Photovoltaic Park. We utilized the DPSIR framework to create an index system for determining the ecological and environmental impacts of large-scale photovoltaic development in desert regions and evaluate the ecological and environmental effects of the Gonghe Photovoltaic Park (Fig. 2). Based on the logical and causal relationships between the subsystems of the model, the driving forces include the local population, economy, and society, while natural factors, such as surface effective radiation and water vapour evaporation, put pressure on the ecological and environmental system, leading to changes in vegetation, soil, climate, and other environmental states, which in turn affect soil nutrient content, climate regulation, and biodiversity. To protect ecosystem security, human society is taking action against these changes, such as improving regulatory capabilities, expanding financial investment, and strengthening ecological remediation. By considering the environmental characteristics of desert photovoltaic parks, official technical specifications from the Ministry of Environmental Protection of China, and relevant literature reviews, we selected evaluation indicators for our four-layer indicator system, the target layer representing the ecological and environmental status of the study area, and the plan layer containing Driving (D), Pressure (P), Status (S), Impact (I), and Response (R), which is further subdivided through the factor layer. The indicator layer divided the factor layer into quantifiable specific indicators and we ultimately selected 57 indicator factors, as shown in Fig. 3.

The logical relationships within the Driving-Force-Pressure-Status-Impact-Response (DPSIR) model. In this model, the driving force (D) associated with human activities results in fluctuations in ecosystem pressure (P), which in turn alters the state of the ecosystem (S) and subsequently impacts the ecosystem (I). This dynamic also prompts governmental or societal responses (R) to address the driving forces.

Index system for evaluating the ecological and environmental effects of large-scale desert photovoltaic parks.

Determination of the indicator weight based on the entropy weight method

Standardization of indicator variables

After establishing an evaluation index system for ecological and environmental effects in desert photovoltaic areas. Due to the varying collection periods of different types of indicators, the average value for each indicator within the observation period is calculated separately for WPS, TPS, and OPS. In addition, data standardization is necessary because of the differences in indicator units, dimensions, and positive and negative values23.

If the indicator is positive, its calculation method can be seen in Eq. (1):

$$\:{S}_{ij}=\frac{{x}_{ij}-{minx}_{j}}{{maxx}_{j}-{minx}_{j}}$$

(1)

If the indicator is negative, its calculation method can be seen in Eq. (2):

$$\:{S}_{ij}=\frac{max{x}_{j}-{x}_{ij}}{{maxx}_{j}-{minx}_{j}}$$

(2)

where the standardized value calculated is represented by Sij, and xij denotes the average observation result of the j-th indicator in the i-th evaluation area. Moreover, maxxj and minxj signify the maximum and minimum values of the average observation results of the j-th indicator in WPS, TPS, and OPS, respectively.

Determination of indicator weight

Determining the weight of evaluation indicators is crucial in evaluating ecological and environmental impacts; the rationality of weights can significantly affect the evaluation results. Currently, widely adopted methods include the Delphi method, the analytic hierarchy process, and the entropy weight method24,25,26. The entropy weight method is a data-driven, objective weighting method that leverages data to eliminate subjective influence and objectively reflect reality. Hence, in this study, we used the entropy weight method to determine indicator weights in the DPSIR model. During the process of entropy weight weighting, if an indicator has a smaller entropy value, its contribution to the evaluation system is greater, and its weight is greater27. Conversely, the weight of the evaluation index decreases as the entropy increases.

Entropy calculation

To circumvent the occurrence of null values in the standardized data, all standardized outcomes are augmented by 0.1 to satisfy the calculation prerequisites.

The proportion of the j-th indicator in the i-th region is calculated, Pij:

$$\:{P}_{ij}=\frac{{S}_{ij}}{\sum\:_{i=1}^{m}{S}_{ij}}$$

(3)

The entropy value (ej) of each indicator in the indicator system is calculated:

$$\:{e}_{j}=-k{\sum\:}_{i=1}^{m}{P}_{ij}ln{P}_{ij}$$

(4)

where \(\:k=\frac{1}{lnm}\), m is the total number of evaluation areas.

Index weight calculation

The importance of the indicators can be preliminarily determined based on the entropy values calculated for each indicator, followed by the calculation of the weights (Wj) using Eq. 5.

$$\:{W}_{j}=\frac{1-{e}_{j}}{\sum\:_{j=1}^{n}\left(1-{e}_{j}\right)}$$

(5)

Comprehensive evaluation of the ecological and environmental effects of the desert photovoltaic park

Based on the established index system for the evaluation of ecological and environmental effects in desert photovoltaic development zones, the comprehensive index method was employed to calculate the comprehensive ecological and environmental effect index for various locations within the Gonghe photovoltaic zone. Subsequently, the ecological and environmental effects of the study area were comprehensively evaluated using the “Technical Specification for Ecological and Environmental Status” (HJ/T 192-2015)28. The calculation method for the comprehensive ecological and environmental indices is described below:

$$\:EHI=\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{P}_{ij}{W}_{i}$$

(6)

where EHI is the comprehensive index of ecological and environmental conditions and n is the number of indicators.

The Technical Specification for Ecological and Environmental Status (HJ/T 192-2015) divides the comprehensive index of environmental conditions into five categories: “worse”, “poor”, “general”, “good” and “excellent”, as demonstrated in Table 2.

Results and discussions

Distribution characteristics and influencing factors of indicator scores

By comparing the scores of various evaluation indicators and considering the environmental characteristics and management modes of desert photovoltaic parks, this study analysed the impact of large-scale desert photovoltaic development on the scores of different indicators within the DPSIR subsystem.

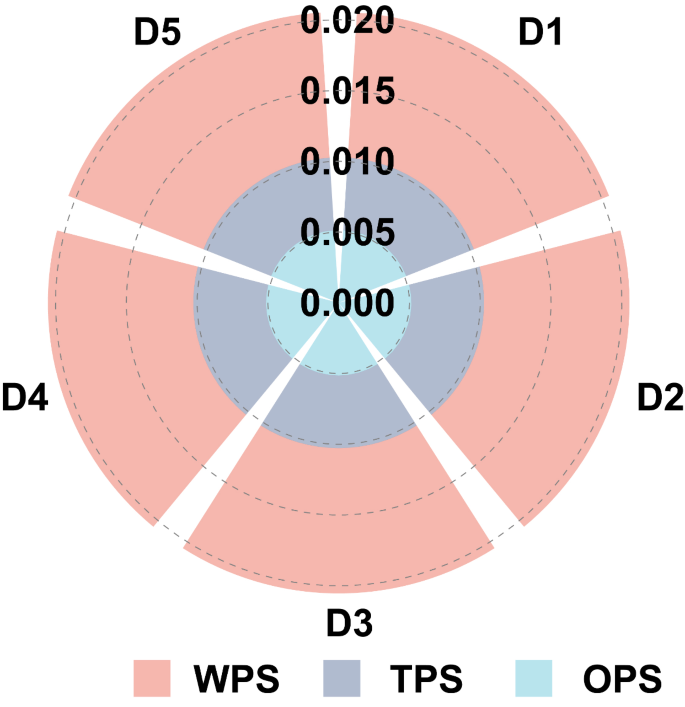

Driving

Considering the driving factors, as solar photovoltaic development continuously increased, the population growth rate (D1), per capita GDP (D2), energy conservation and environmental protection growth rate (D3), photovoltaic power generation growth rate (D4) and urbanization rate (D5) at the photovoltaic power site (WPS) were greater than those at the transitional site (TPS) and outside the site (OPS). At the WPS, the score for each indicator was 0.0103, which was approximately two times greater than the scores for the indicators at the TPS and OPS (Fig. 4). This indicates that driving factors are a vital aspect in promoting an improved desert ecological environment.

In recent years, the construction of large-scale photovoltaic power stations has resulted in energy transformation and has impacted the operation of power stations; migrant workers are urgently needed in the operation of these power stations, which solves the employment problems of some local residents. Moreover, the integration of the photovoltaic industry with agriculture and animal husbandry has been achieved29,30, which significantly increases the per capita income of residents and promotes regional urbanization development. Furthermore, as a clean and renewable energy source, photovoltaic energy has contributed substantially to energy conservation, emission reduction, and environmental protection by fundamentally reducing greenhouse gas emissions such as CO2 and N2O31,32,33.

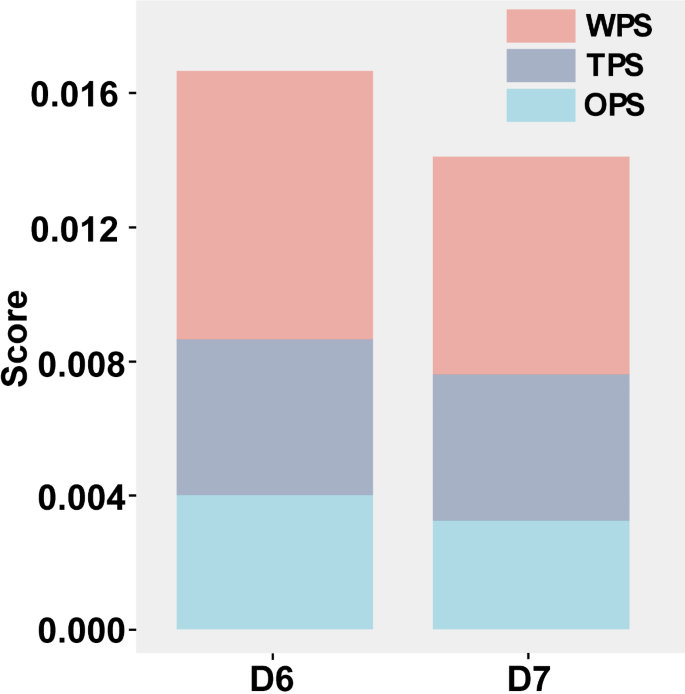

Pressure

In the pressure layer, surface effective radiation (D6) and evaporation (D7) scores decreased from the photovoltaic power site to the periphery, following the sequence WPS > TPS > OPS. The D6 score decreased from 0.008 at the WPS to 0.004 at the OPS. The reduction in D7 was even more significant, decreasing from 0.0065 at the WPS to 0.0032 at the OPS, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Notably, the P value of the WPS was greater than that of the TPS and OPS, suggesting that the construction of photovoltaic power plants could alleviate environmental pressure.

Numerous studies have shown a positive correlation between evaporation and surface effective radiation34,35,36. Photovoltaic panels absorb direct solar radiation, leading to lower soil moisture evaporation and significant differences in soil evaporation between areas covered by panels and areas without panels. Additionally, panels block longwave radiation from the ground to the atmosphere, which affects the radiative equilibrium of the Earth’s atmosphere interface2. This contributes to changes in surface effective radiation.

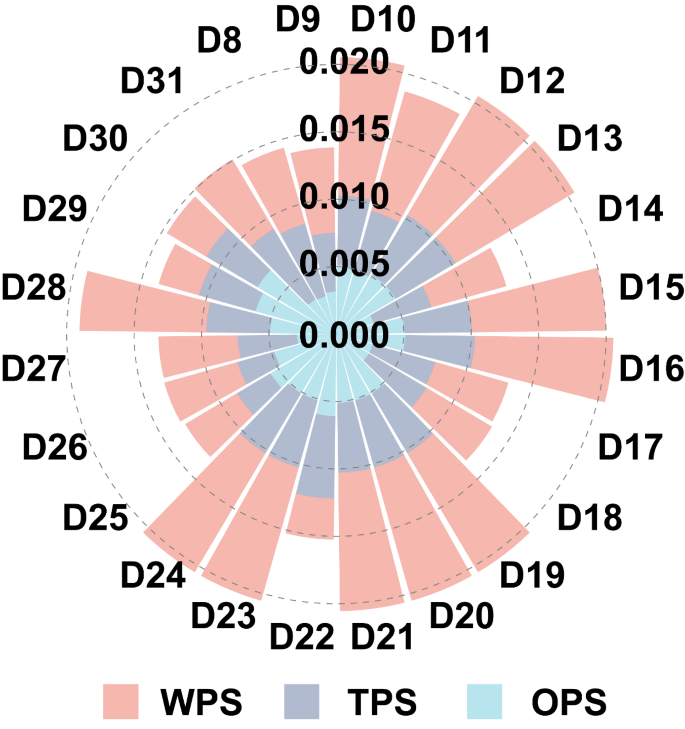

Status

The state layer analysis revealed that several variables had high scores, including vegetation species number (D10), vegetation evenness index (D12), 0–40 cm silt content (D13), pH (D16), bacterial abundance (D19), the bacterial Simpson index (D20), the bacterial evenness index (D21), the archaeal Simpson index (D23), and the archaeal evenness index (D24). The scores for each variable at the WPS (0.0103) were greater than those at both the TPS (0.0051) and OPS (0.0051). Furthermore, these variables exhibited the greatest magnitude of changes within and outside the photovoltaic field, indicating their significant impact on the state layer, as shown in Fig. 6. Furthermore, the water content (D15), atmospheric pressure (D28), vegetation Simpson index (D11), sward thickness (D9), and daily net radiation (D31) were relatively high at the WPS, with values greater than 0.006. The scores for the other variables decreased from the WPS to the OPS, with the exception of D31, where the score decreased in the order of TPS > WPS > OPS. The electrical conductivity (D27), perennial cushion grass (D8), bulk density (D14), subterranean biomass (D18), salinity (D17), soil heat flux (D26), Nemerow comprehensive pollution index (D25), archaebacterial abundance (D22), average daily photosynthetically active radiation (D29), and rainfall (D30) scores were all relatively low. In particular, the D25 score at the OPS exceeded that at the WPS. The D22, D29, and D30 scores increased from the WPS to the OPS, while the scores of the other indicators decreased from the WPS to the OPS.

Recent research has demonstrated the positive impact of photovoltaic power stations on soil evaporation and water content. The construction of these power stations has led to a reduction in soil evaporation, while the cleaning of photovoltaic panels has increased the water content of the soil located under the panels37. The cleaning frequency of photovoltaic panels in this study is once a month, as a result, the growth conditions for vegetation indirectly improved. This has led to an increase in both vegetation species and biomass. Specifically, the species richness, Shannon‒Wiener diversity index, Simpson index, and mat herb biomass at the WPS were significantly greater than those at the OPS38. With the operation of photovoltaic power plants, the soil particles at the WPS tended to be finer than those at the TPS and OPS39,40, resulting in a greater proportion of 0–40 cm powder particles at the WPS. Solar radiation indirectly regulates plant and microbial communities by changing soil water and thermal conditions. Studies have shown significant differences in daily net radiation between photovoltaic power plants because photovoltaic panels absorb direct solar radiation and because photovoltaic panels block longwave radiation from the surface to the atmosphere41. Overall, the construction of photovoltaic power plants has a positive impact on the regulation of ecological and environmental effects.

Impact

The scores of each indicator inside and outside the field in the impact layer are shown in Fig. 7. The overall trend decreased from the inside to the outside of the field. In the impact layer of the WPS, the scores of soil carbon sequestration (D32), available potassium (D39), available phosphorus (D40), bacterial diversity (D48), archaeal diversity (D49), air humidity (D43), and total phosphorous (D36) were relatively high, all greater than 0.007. The spatial distributions of all the indicators at the WPS were greater than those at the TPS and OPS. Apart from the higher D43 score at the OPS (0.0048) than at the TPS (0.0043) and the slightly greater D36 score at the TPS (0.0046) than at the OPS (0.0039), the scores of the remaining indicators at the TPS and OPS were the same, at 0.0051. At the WPS, the scores of aboveground biomass (D41), organic matter (D41), and total potassium (D37) were slightly lower than those of the high-scoring indicators mentioned earlier. However, the temperature (D42), plant carbon sequestration (D33), plant oxygen release (D34), total nitrogen (D35), available nitrogen (D38), wind speed (D44), soil temperature (D45), and plant diversity (D47) were relatively low.

Soil is one of the most important carbon reservoirs in terrestrial ecosystems, and soil carbon sequestration is an effective way to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions2. The construction of photovoltaic power stations can increase the soil moisture content and the soil particle content, thereby enhancing the soil’s carbon sequestration ability. In addition, soil available potassium and available phosphorus are important indicators of recent soil potassium and phosphorus contents. Several studies have suggested that the sensitivity of soil available nutrients to land-use change is greater than that of the total nutrients found in the soil42. Therefore, there are significant variations in soil available amounts of potassium and phosphorus between areas within and outside photovoltaic fields. In contrast, the layout of photovoltaic panels results in a decrease in wind speed and solar radiation, leading to an increase in air humidity. Such changes in soil water and thermal conditions, along with changes in vegetation communities, have resulted in a minor increase in bacterial and archaeal diversity beneath photovoltaic panels compared to the respective control areas outside.

Response

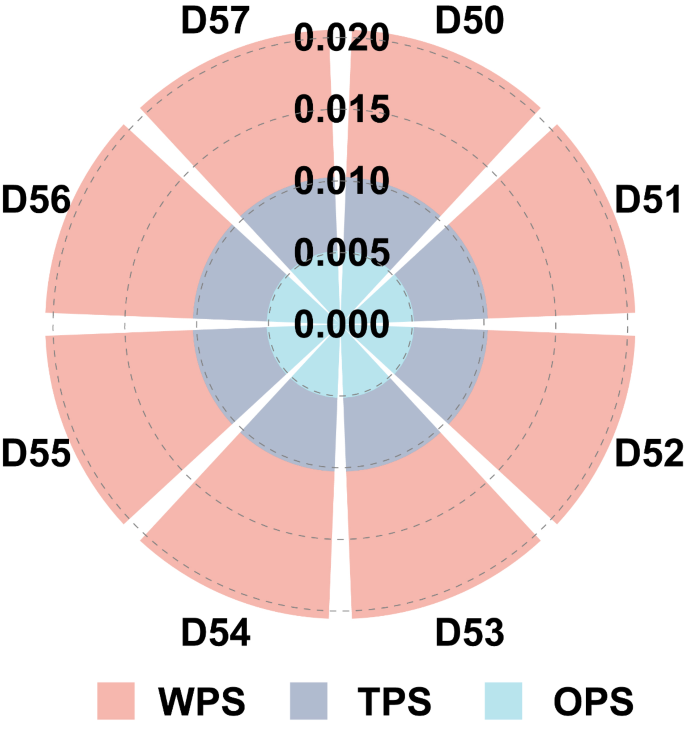

Figure 8 shows the scores of various indicators, including regulatory capacity (D50), long-term management mechanism construction (D51), proportion of environmental investment to GDP (D52), photovoltaic area (D53), photovoltaic value (D54), photovoltaic panel cleaning frequency (D55), vegetation coverage (D57), and total soil erosion control degree (D57), in response to the WPS, TPS, and OPS. The scores trended in the following order: WPS (0.0103) > TPS (0.0051) = OPS (0.0051). This indicates the effectiveness of the response measures formulated by the government and society in improving the ecological and environmental conditions of the site.

The contributions of within-site indicators to the ecological environmental effects are significantly greater than those of the transition site and the outside site, mainly due to the continuous expansion of desert photovoltaic power plants, strengthened government, societal and economic responses, and soil and water conservation measures. However, the analysis indicated that the ecological environment still faces tremendous pressure, with lower scores for various indicators in the status layer and lower scores for onsite indicators such as fungal abundance and daily photosynthetic radiation than outside the zone. These results may result in more significant impacts in the future; therefore, more comprehensive response measures should be taken to improve the ecological environment in the region.

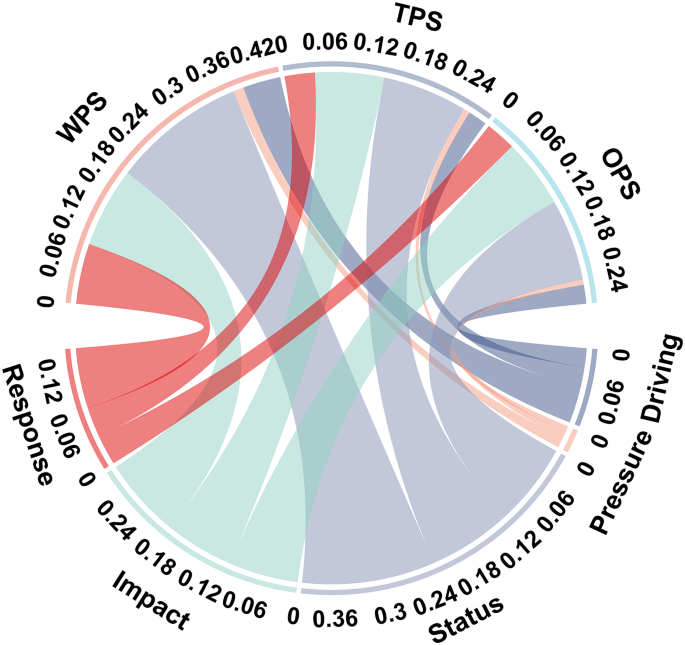

Comprehensive evaluation of the ecological and environmental effects of the desert photovoltaic park

There were significant spatial differences in the ecological and environmental conditions among desert photovoltaic development zones (Table 3; Fig. 9). The comprehensive indices of the ecological and environmental conditions in the photovoltaic field, transition zone, and off-site were 0.4393, 0.2858, and 0.2802, respectively. Photovoltaic development in desert areas has significantly improved local ecological and environmental conditions. At the WPS, the Status and Impact scores were 0.182 and 0.11, respectively, indicating a significant impact on the ecological environment of the study area. More specifically, photovoltaic development has primarily induced positive effects on the region’s microclimate, physical and chemical properties of the soil, and diversity of the plant and microbial communities, as supported by recent findings43. The third factor to be considered is the response index. The response index at the photovoltaic power site (WPS) was significantly greater (0.082) than that at the TPS (0.041) and OPS (0.041). This result is attributed to the increased attention given to environmental preservation in desert areas due to the construction of photovoltaic power stations. Management departments have implemented a number of effective measures to improve the ecological environment. These measures include the implementation of soil and water conservation, increased investment, and enhanced regulatory capabilities. The WPS has a higher pressure evaluation score than the TPS and OPS because photovoltaic panels absorb direct solar radiation and reflect a small amount of heat back into the atmosphere as long waves. This reduces atmospheric radiation to the soil, which decreases soil evaporation. Regarding driving, the WPS has a greater evaluation value than the TPS and OPS due to the construction of photovoltaic power stations that solve employment problems for local residents and promote economic development. Additionally, photovoltaic energy is a clean source that creates opportunities for energy conservation and environmental protection.

Spatial scale comprehensive index distribution of the ecological and environmental status of desert photovoltaic power stations.

An assessment of the ecological environmental status of the desert photovoltaic development zone was conducted based on Table 2, including an evaluation of the onsite, in-transition, and off-site zones (refer to Table 3). Specifically, the ecological environmental status of the WPS was deemed “general”, contrasting with that of the TPS and OPS, which were considered “poor”. The comprehensive index of the TPS was slightly greater than that of the OPS. These findings indicate the essential role played by the construction of photovoltaic power stations in ecological environmental governance in desert areas. This impact is mainly attributed to the influence on the microclimate and the soil, plant, and microbial communities in these regions. Notwithstanding such efforts, a significant scope for improvement still exists for achieving optimal ecological environmental conditions. Optimizing response layer indicators is an approach that may help achieve such improvements.

Conclusion

A desert photovoltaic park ecological environment effect indicator system was developed using the DPSIR framework to assess the ecological impact of the Qinghai Gonghe Photovoltaic Park, a typical high-altitude desert photovoltaic park. The weight of indicators was calculated using the entropy weight method, The distribution characteristics of the scores of various indicators in the DPSIR framework subsystems were analysed, and the relationships between subsystems and environmental variables were revealed, and the ecological environment effect of the park was reflected through the EHI comprehensive index. The evaluation highlighted significant differences in ecological conditions between different sections of the Gonghe Photovoltaic Power Station, with WPS having average ecological conditions and TPS and OPS showing poor conditions. Spatial variations in evaluation results across subsystems indicate that desert photovoltaic development has positively impacted the ecological environment. The index system constructed in this study helps to clarify the changes in the driving forces, pressures, states, impacts, and responses of desert photovoltaic power plants and their comprehensive relationships. The use of different levels of indicators is an effective method for examining integrated environmental decision-making and can help managers make improved decisions.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chang, R., Luo, Y. & Zhu, R. Simulated local climatic impacts of large-scale photovoltaics over the barren area of Qinghai, China. Renew. Energy. 145, 478–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2019.06.059 (2020).

Jiang, J., Gao, X., Lv, Q., Li, Z. & Li, P. Observed impacts of utility-scale photovoltaic plant on local air temperature and energy partitioning in the barren areas. Renew. Energy. 174, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene (2021).

Lambert, Q., Bischoff, A., Cueff, S., Cluchier, A. & Gros, R. Effects of solar park construction and solar panels on soil quality, microclimate, CO2 effluxes, and vegetation under a Mediterranean climate. Land Degrad. Dev.32(18), 5190–5202. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4101 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Solar photovoltaic panels significantly promote vegetation recovery by modifying the soil surface microhabitats in an arid sandy ecosystem. Land Degrad. Dev.30(18), 2177–2186. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3408 (2019).

Mahmud, M. A. P., Huda, N., Farjana, S. H. & Lang, C. Environmental impacts of solar-photovoltaic and solar-thermal systems with life-cycle assessment. Energies. 11(9), 2346. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11092346 (2018).

Silva, P. D. & Branco, G. D. Is floating photovoltaic better than conventional photovoltaic? Assessing environmental impacts. Impact Assess. Project Apprais.36(5), 390–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2018.1477498 (2018).

Turney, D. & Fthenakis, V. Environmental impacts from the installation and operation of large-scale solar power plants. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.15(6), 3261–3270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2011.04.023 (2011).

Liu, X., Liu, H., Chen, J., Liu, T. & Deng, Z. Evaluating the sustainability of marine industrial parks based on the DPSIR framework. J. Clean. Prod.188, 158–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.271 (2018).

Tesfaldet, Y. T. & Ndeh, N. T. Assessing face masks in the environment by means of the DPSIR framework. Sci. Total Environ.814, 152859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152859 (2022).

Zhou, G. et al. Evaluating low-carbon city initiatives from the DPSIR framework perspective. Habitat. Int.50, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.09.001 (2015).

Mosaffaie, J., Salehpour Jam, A., Tabatabaei, M. R. & Kousari, M. R. Trend assessment of the watershed health based on DPSIR framework. Land Use Policy100, 104911. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104911 (2021).

Qinghai Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Qinghai Statistical Yearbook 2020, 47–53. (China statistics pressure, 2020).

Qinghai Provincial Agricultural Resources Zoning Office. Qinghai Soil, 89–92 (China Agricultural Pressure, 1997).

Wei, T. & Wu, B. Changes in vegetation community characteristics during sandy desertification in the Gonghe basin. J. Ecol. Environ.20 (12), 1788–1793. https://doi.org/10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2011.12.002 (2011).

Zhang, D. Quantitative analysis of the impact factors of land desertification in the Gonghe basin of Qinghai Province. J. Desert Res. (01), 60–63. (2000).

Hainan Autonomous Prefecture Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Statistics, Hainan Autonomous Prefecture Survey Team. Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of Hainan Autonomous Prefecture in 2020. 45–47. (Hainan Daily Pressure, 2020).

Wang, H. Work Report of Hainan Autonomous Prefecture Government in 2020, 31–37. (Hainan Daily Pressure, 2020).

Farquhar, G. D. & Von Caemmerer, S. Modelling of photosynthetic response to environmental conditions. In Physiological Plant Ecology II: Water Relations and Carbon Assimilation. 549–587. (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, (1982).

De Pury, D. G. G. & Farquhar, G. D. Simple scaling of photosynthesis from leaves to canopies without the errors of big-leaf models. Plant. Cell. Environ.20(5), 537–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.1997.00094.x (1997).

Wu, X. et al. Analysis of ecological carrying capacity using a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method. Ecol. Ind.113, 106243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2020.106243 (2020).

Xu, S. et al. The fuzzy comprehensive evaluation (FCE) and the principal component analysis (PCA) model simulation and its applications in water quality assessment of Nansi Lake Basin, China. Environ. Eng. Res.26(2), 200022. https://doi.org/10.4491/eer.2020.022 (2021).

Westing, A. H. The environmental component of comprehensive security. Bull. Peace Proposals. 20(2), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/096701068902000203 (1989).

Zhao, D., Li, C., Wang, Q. & Yuan, J. Comprehensive evaluation of national electric power development based on cloud model and entropy method and TOPSIS: A case study in 11 countries. J. Clean. Prod.277, 123190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123190 (2020).

Ahmed, F. & Kilic, K. Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy process: A performance analysis of various algorithms. Fuzzy Sets Syst.362, 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2018.08.009 (2019).

Danica, F. H., Tamara, D., May, D., Meta, N. & Mitja, H. F. Delphi method: strengths and weaknesses. Adv. Methodol. Stat.16(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.51936/fcfm6982 (2019).

Hamid, T., Al-Jumeily, D. & Mustafina, J. Evaluation of the dynamic cybersecurity risk using the entropy weight method. Technol. Smart Futur. 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60137-3_13 (2018).

Zhu, Y., Tian, D. & Yan, F. Effectiveness of entropy weight method in decision-making. Math. Probl. Eng.2020(3564835). https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3564835 (2020).

State Environmental Protection Administration. Technical Specification for Ecological and Environment Assessment, 13. (China Environmental Science Pressure, 2006).

Huang, K. et al. Sustainable and intelligent phytoprotection in photovoltaic agriculture: new challenges and opportunities. Electronics. 12(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics12051221 (2023).

He, Y., Che, Y., Lyu, Y., Lu, Y. & Zhang, Y. Social benefit evaluation of China’s photovoltaic poverty alleviation project. Renew. Energy. 187, 1065–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.013 (2022).

Ren, F. R., Tian, Z., Liu, J. & Shen, Y. R. Analysis of CO2 emission reduction contribution and efficiency of China’s solar photovoltaic industry: Based on input-output perspective. Energy199, 117493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2020.117493 (2020).

Wang, M., Mao, X., Gao, Y. & He, F. Potential of carbon emission reduction and financial feasibility of urban rooftop photovoltaic power generation in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod.203, 1119–1131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.350 (2018).

Olivieri, L., Caamaño-Martín, E., Sassenou, L. N. & Olivieri, F. Contribution of photovoltaic distributed generation to the transition towards an emission-free supply to university campus: technical, economic feasibility and carbon emission reduction at the Universidad Politécnica De Madrid. Renew. Energy. 162, 1703–1714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2020.09.120 (2020).

Yue, S., Guo, M., Zou, P., Wu, W. & Zhou, X. Effects of photovoltaic panels on soil temperature and moisture in desert areas. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.28(14), 17506–17518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11742-8 (2021).

Heck, K., Coltman, E., Schneider, J. & Helmig, R. Influence of radiation on evaporation rates: a numerical analysis. Water Resour. Res. 56(10), e2020WR027332 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027332

Yang, Y. & Roderick, M. L. Radiation, surface temperature and evaporation over wet surfaces. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc.145(720), 1118–1129. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.3481 (2019).

Hassanpour Adeh, E., Selker, J. S. & Higgins, C. W. Remarkable agrivoltaic influence on soil moisture, micrometeorology and water-use efficiency. Plos One. 13(11), e0203256. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203256 (2018).

Zhang, Z. et al. Study on the species diversity of photovoltaic power plant communities in the desert area of the Hexi corridor. J. Northwest For Univ.35(02), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-7461 (2020).

Choi, C. S. et al. Effects of revegetation on soil physical and chemical properties in solar photovoltaic infrastructure. Front. Environ. Sci.8, 140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.00140 (2020).

Noor, N. F. M. & Reeza, A. A. Effects of solar photovoltaic installation on microclimate and soil properties in UiTM 50MWac Solar Park, Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci.1059(1), 012031 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. A comparative study on the surface radiation characteristics of photovoltaic power plant in the Gobi desert. Renew. Energy. 182, 764–771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.10.054 (2022).

Wang, J., Fu, B., Qiu, Y. & Chen, L. Soil nutrients in relation to land use and landscape position in the semi-arid small catchment on the loess plateau in China. J. Arid Environ.48(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.2000.0763 (2001).

Zhang, Y., Tian, Z., Liu, B., Chen, S. & Wu, J. Effects of photovoltaic power station construction on terrestrial ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Front. Ecol. Evol.11, 1151182. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1151182 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the editors and reviewers who have put considerable time and effort into their comments on this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Qinghai Province Major Science and Technology Projects (Grant No. 2021-SF-A7-2); and Scientific Research Program Funded by Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (grant number 23JY060).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, W., Chen, H., Li, C. et al. Assessment of the ecological and environmental effects of large-scale photovoltaic development in desert areas. Sci Rep 14, 22456 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72860-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-72860-8