In the initial set of experiments we focused on detecting neutron emission associated with rapidly collapsing deuterium bubbles in mineral oil under the influence of acoustic drive. To create the bubbles we have filled the reactor headspace with pure deuterium gas while circulating the oil through the venturi nozzle. We have conducted hundreds of tests runs trying various ambient bubble sizes (from 100 nm to 100 micron), various ambient pressure (from 1E−4 to 1000 Torr), various acoustic drive amplitude (from 1 to 10,000 psi), various acoustic frequencies (from 20 to 100 kHz) and various surfactants (SDS, Triton-X, PFA) but failed to detect any neutron emission above background level. We used a borax castle to reduce background counts to below 1 CPM and on some experiments employed up to twelve 3He neutron counters 1.25″ diameter by 8″ encircling the reactor for nearly 2π solid angle coverage (the reactor top and bottom plate as well as the viewport were not covered). Yet we failed to observe even a 1% increase in neutron counts above background during these experiments.

We have also tried various Xe + D2 mixtures as suggested in Ref.3 but with the same lack of excess neutrons.

For the second set of experiments we shifted away using bubbles and switched to D2O droplets. As before, we have systematically combed the parametric space while varying the droplet concentration from extremely concentrated (the oil was opaque and milky in appearance) to extremely dilute (the oil was clear in appearance, but we could detect the droplets using the HELOS laser). Once again we did not detect any excess neutrons at 1% level above background.

While experimenting with the droplets we made the following observations:

-

(1)

Microdroplets in oil are exceedingly stable against cavitation and degassing; even intense (> 1000 psi amplitude) acoustic drive under vacuum was very inefficient in converting droplets into bubbles.

-

(2)

Cavitation was all but absent even in presence of surfactants; we did not detect significant levels of cavitation noise under most conditions.

-

(3)

We could remove the microdroplets only by filtering.

-

(4)

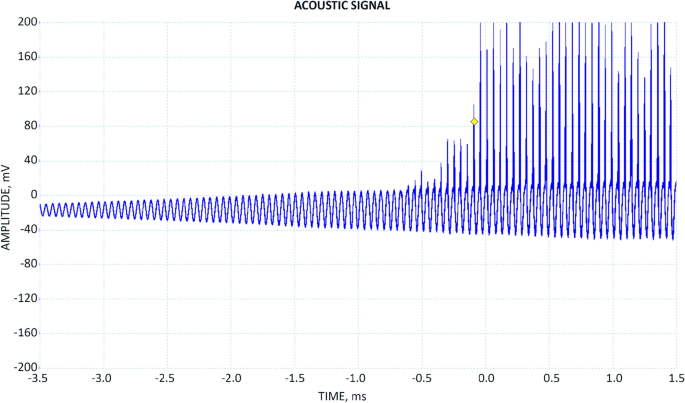

Sometimes, when the droplet size was matched with the amplitude and frequency of the acoustic drive we observed stupendous ‘secondary’ acoustic peaks that we hypothesize originated from constructive interference of the outgoing shockwaves originating from rebounding or oscillating bubbles4 (Fig. 4).

An acoustic signal from the reactor: small-amplitude 20 kHz acoustic wave corresponds to the external acoustic drive applied to the reactor, clipping acoustic pulses are thought to arise from constructive interference of the outgoing shockwaves launched by the rebounding bubbles.

These extreme peaks sometimes were in excess of 24,000 psi to where they saturated the PCB transducer and the actual pulse magnitude could not be read. Several times the transducer got damaged. Two times the 6″ quartz viewport of the reactor got cracked or completely shattered. It is hard to imagine what sort of acoustic magnitude was achieved inside the reactor to make this destruction possible. The peaks tended to be stronger and easier to obtain when the emulsion concentration was very high and the reactor oil was milky in appearance.

During the third set of experiments we introduced samples of suspension that contained both Ti/D particles and D2O droplets into the reactor and after thorough mixing subjected the working fluid to a 20 kHz acoustic drive at maximum power with the 0.01 s on/0.01 s off duty cycle. Almost immediately we registered a significant neutron flux that occasionally exceeded 200 CPS/12,000 CPM (we did not use a borax castle and the background counts were below 0.5 CPS/30 CPM). This happened when a large suspension sample (~ 0.5 L) was introduced into the reactor at ambient pressure and the reactor oil consistency was milky in appearance. The actual neutron flux could have been even higher since we did not use any moderator around our detectors on the account that the reactor oil itself will thermalize neutrons originating from within the reactor.

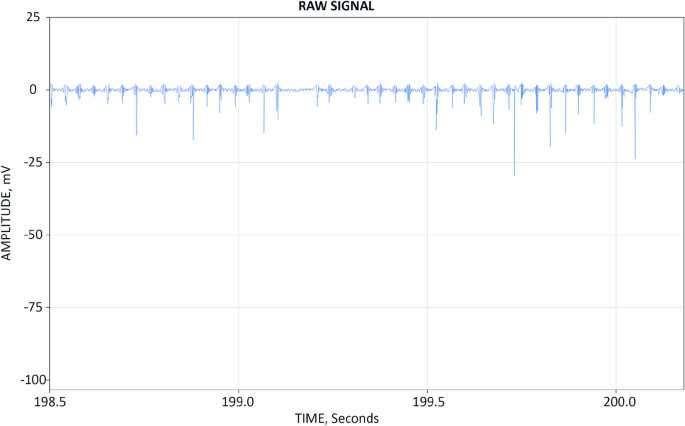

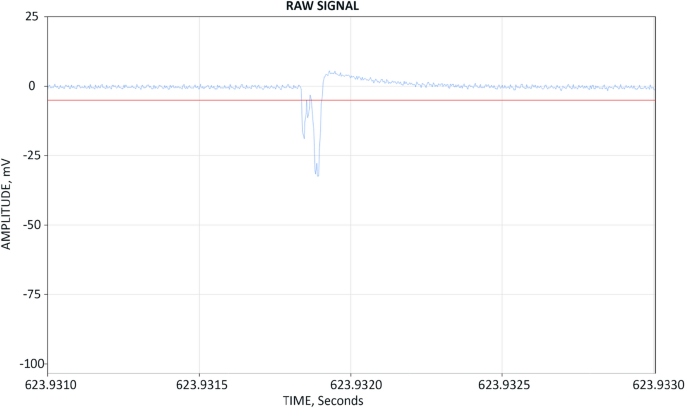

When we examined the raw detector signal (Fig. 5) we observed numerous neutron events evenly spaced in time. The neutron event clusters correlated neatly with the acoustic drive duty cycle. specifically, the neutron events predominantly occurred when the acoustic drive was on. This was evident through the EM noise that leaked into the detector signal due to capacitive coupling between the reactor and the detector bank. This noise appeared as low magnitude high frequency oscillations below the neutron detection threshold level.

The raw neutron detector signal; neutron events (thin vertical lines) correlate neatly with EM noise (low magnitude high frequency oscillations below the neutron detection threshold level) due to capacitive coupling between the neutron detector bank and the piezoelectric driver; the noise period coincides with the 0.01 s on/off piezoelectric driver duty cycle.

We were able to repeat this high-flux experiment several times in the course of two days with similar results.

To further study the phenomenon we changed the experimental protocol as follows:

-

(1)

We started introducing just 1 mL of suspension into the reactor in order to obtain consistently repeatable results under better controlled conditions for a systematic study.

-

(2)

We switched to using the neutron detector bank depicted on Fig. 2 as with it we could use a grounded copper sheet to break the capacitive coupling between the reactor and the detector bank and thus eliminate the EM interference from the piezoelectric driver and thus capture a much cleaner detector signal: the copious amounts of neutrons, EM noise and numerous overlapping multi-neutron events from the previous experiments prevented us from obtaining a clean thermal neutron spectrum, which we felt was necessary to observe in order to remove all doubts about the nature of the emission.

-

(3)

We used borax castle to reduce the background counts to below 1 CPM.

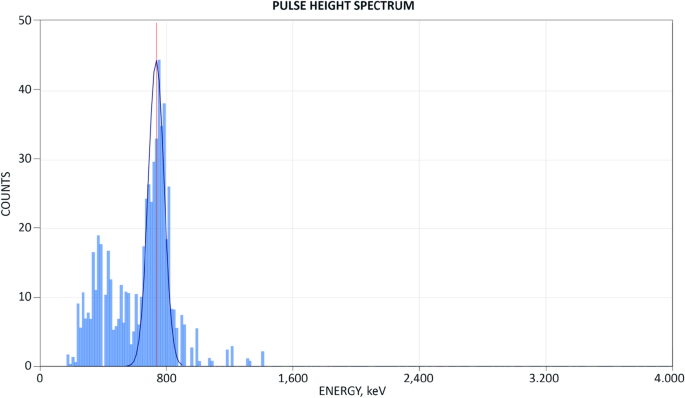

As a result of the change of protocol we have been able to conduct numerous successful experiments in the following months and captured a clean thermal neutron spectrum depicted on Fig. 6.

The spectrum on Fig. 6 was acquired during 23 min of the reactor operation. We have captured 1497 count rate samples, recorded and stored the raw detector signal in its entirety. The mean count rate during the experiment was 0.2 CPS/12 CPM; the mean background count rate (which was established by sampling the background for 20 h) was below 0.01 CPS/0.6 CPM. The difference between the ‘experiment’ and ‘background’ mean count rates in this particular example is 20× and is highly statistically significant (p < 0.000).

During another similar 34 min run the mean ‘experiment’ count rate was 1 CPS/59.4 CPM or 100 times in excess of the background.

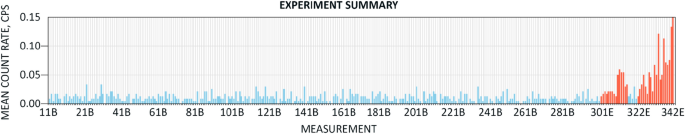

Figure 7 depicts the plot of the mean count rates of 300 four-minute ‘background’ measurements (20 h total), followed by 16 four-minute ‘experiment’ measurements, followed by further 5 ‘background’ measurements ending with the additional 21 ‘experiment’ measurements. The tenfold jump in the count rates when the acoustic drive is activated is clearly evident.

The mean count rates of a long sequence of 4 min measurements: the blue bars correspond to the ‘background’ (reactor off) measurements, the red bars represent the ‘experiment’ (reactor on) measurements; note that the counts briefly return to the background level when the reactor is turned off during the measurements 317 to 321.

In some experiments we observed multiple neutron events that are spaced so tightly that the software algorithm could not resolve their pulse height accurately (Fig. 8). When this happened the resulting neutron spectrum got predictably distorted.

Our attempts to measure gamma emission from the reactor using a Bicron 2M2 2″ NaI(Tl) scintillator connected to the ANL yielded counts and spectra consistent with the background. The detector was placed in immediate proximity with the reactor wall but without making physical contact. Due to the relatively low neutron flux it is possible that the accompanied gamma flux was too weak to be detected due to absorption in the reactor oil and in the reactor wall.