Main

Hormone receptor-positive (HR+) breast cancer accounts for 75% of all breast cancer diagnoses, and endocrine therapies represent the mainstay of treatment for patients with HR+ breast cancer, in both adjuvant and metastatic settings1. Yet, the efficacy of standard endocrine therapies is limited by primary or acquired resistance2. Periodic fasting enhances the efficacy of endocrine therapies against HR+ breast cancer and delays acquired therapy resistance in animal models3. Clinical studies indicate that cycles of water-only fasting or fasting-mimicking diets (FMDs; low-calorie, low-protein and low-sugar, vegan diets that recreate the metabolic effects of fasting4) are feasible and safe in patients with different tumour types, such as breast, melanoma, colorectal, lung and gynaecological cancers5,6,7.

We previously reported that fasting enhances the efficacy of endocrine therapies in HR+ breast cancer3. However, the mechanisms that underlie this effect remain unknown. Moreover, adjuvant endocrine regimens involve five to ten years of continuous daily treatment8, making prolonged combined dietary intervention during endocrine therapy highly challenging to adhere to. Here we investigated the biological mechanisms at the basis of fasting enhancement of tamoxifen (TMX) efficacy, one of the most commonly utilized endocrine therapies, with the aim of identifying therapeutic strategies that phenocopy beneficial effects of fasting or FMD in patients with HR+ breast cancer, and which could be potentially adopted in place of fasting or FMD.

Fasting reprogrammes the cancer epigenome

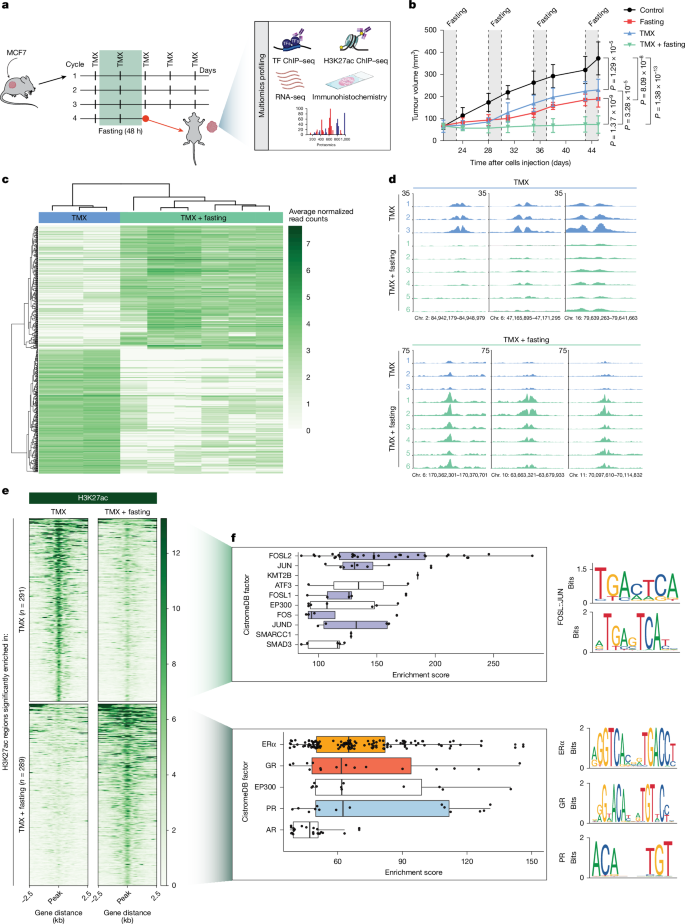

In mice xenografted with the human HR+ breast cancer cell line MCF7, weekly cycles of 48 h fasting showed synergistic in vivo anti-tumour effects when combined with TMX (Fig. 1a,b and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b), confirming our previous observations3. To comprehensively define the biological effect of fasting on tumour cell biology, we performed extensive multiomic analyses on the collected tumour material, including transcriptomics, proteomics, immunohistochemistry and chromatin immunoprecipitation with sequencing (ChIP–seq) for the active enhancer/promoter mark H3K27ac9 and many transcription factors (Fig. 1a). A deep analysis of H3K27ac active enhancer/promoter profiles revealed profound epigenomic reprogramming in tumours collected from mice exposed to TMX plus fasting (Fig. 1c–e, Extended Data Fig. 1c–g and Extended Data Table 1) compared with those of tumours that were treated with TMX or fasting alone (Extended Data Fig. 1c,d,f,g). To comprehensively identify transcription factors that potentially act through regulatory elements with altered epigenetic states after fasting, we intersected the genomic coordinates of fasting-affected H3K27ac sites in TMX-treated tumours with data from a publicly available ChIP–seq database10 (n = 13,976) (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Information). H3K27ac sites with decreased signal upon fasting showed enriched occupancy for AP-1 transcription factor family members (including FOSL2, JUN, FOSL1, FOS and JUND)11,12 (Fig. 1f, top), which are known to enhance breast cancer growth and proliferation13. In agreement with this finding, AP-1 inhibition effectively blocked proliferation of the HR+ breast cancer cell lines MCF7 and T47D (Extended Data Fig. 1h), as previously reported14. The H3K27ac sites that were gained after fasting in TMX-treated tumours revealed an enrichment for ERα occupancy in silico (Fig. 1f, bottom), which was confirmed experimentally by ERα ChIP–seq in the same tumours (Extended Data Fig. 1i and Extended Data Table 1). Strong in silico enrichment at fasting-induced H3K27ac regions was also observed for other steroid hormone receptors (SHRs): GR, progesterone receptor (PR) and androgen receptor (AR). (Fig. 1f, bottom). All three SHRs serve as tumour suppressors in ERα+ breast cancer15,16,17,18, yet how their function is affected by dietary interventions remains unknown.

a, Schematic representation of the treatment cycles of mice xenografted with MCF7 cells. After tumours reached a palpable size, mice were treated with the different treatment arms. After four weeks of treatment, tumours were collected and the represented multiomics profiling was performed. TF, transcription factor. Adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), CC BY 4.0. b, Xenograft tumour growth in six-to-eight-week-old female athymic nude mice randomized in control arm (ad libitum diet, n = 6) or fasting alone (48 h weekly, n = 6), TMX alone (n = 6) or TMX combined with fasting (n = 6) treatment arms. n represents number of tumours per treatment group. Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values by mixed-effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (Supplementary Information) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P values from the last day are represented). c, Heat map depicting the differentially enriched H3K27ac regions between TMX alone (n = 3) or TMX plus fasting (n = 6). n represents number of tumours per treatment group. Colour scale represents the average normalized read counts. d, Representative snapshots of differentially enriched regions for H3K27ac between TMX (blue) and TMX plus fasting (green). The genomic coordinates are annotated. e, Heat map of differentially enriched H3K27ac signal in xenografts treated with TMX or TMX plus fasting. f, In silico GIGGLE analysis for factor enrichment at TMX-enriched H3K27ac sites (top left, n = 3) or TMX plus fasting-enriched H3K27ac sites (bottom left, n = 6). n represents number of tumours per treatment group. Right, average binding motifs of the depicted transcription factors, using HOMER software. In box plots, boxes indicate the first and third quartiles, the centre line indicates the median, and the whiskers indicate the first and third quartiles expanded by 1.5× the interquartile range (Supplementary Information).

Fasting activates intratumoural GR and PR

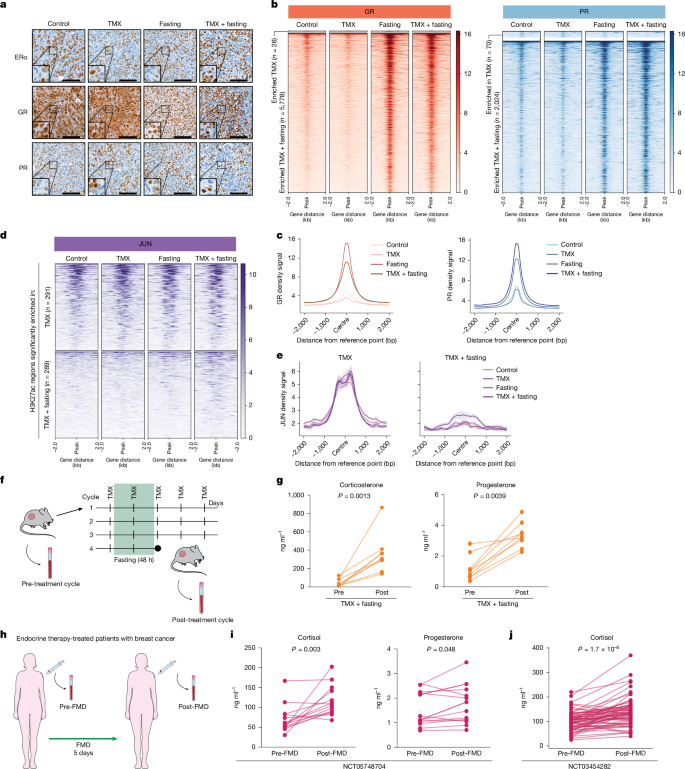

Our in silico analyses suggested altered activity for many SHRs after fasting. To further explore the role of these SHRs in fasting-induced anti-tumour effects, we performed immunohistochemistry analysis to quantify the expression and subcellular localization of ERα, PR and GR in tumours collected from mice exposed to ad libitum diet, fasting, TMX or TMX plus fasting (Fig. 2a). We found that ERα and PR reside mostly in the nucleus, irrespective of their ligand state, as expected17,19, and both their amount and subcellular localization were unaffected by fasting (Fig. 2a). By contrast, fasting—alone or in combination with TMX—strongly increased the nuclear localization of GR, an effect that is typically seen upon GR activation20 (Fig. 2a).

a, Representative immunohistochemistry staining for ERα, GR and PR in MCF7 xenografted tumours in the different treatment arms (n = 4). n represents number of mice per treatment group. Scale bars, 100 μm. b, Heat map depicting ChIP–seq signal for GR and PR in xenografts for all treatment arms. Regions altered in response to fasting in TMX-treated mice are shown. c, Average ChIP–seq signal for GR and PR for all conditions at sites that are enriched in the TMX plus fasting condition, with data centred on the peak, within a ±2-kb window. Data are mean ± s.e.m. d, ChIP–seq heat map signal for JUN in xenografts for all treatment conditions at H3K27ac regions that are differentially enriched in TMX and TMX plus fasting. e, Average JUN ChIP–seq signal for all conditions at H3K27ac regions that are enriched in TMX (left) and TMX plus fasting (right) conditions. Data are centred at the JUN peak, with a ± 2-kb window around the peak. Data are mean ± s.e.m. f, Schematic representation of blood collection schedule. Blood was collected from MCF7 xenografted mice before initiating the first cycle of fasting for all treatment conditions. Blood collection was repeated after the fourth cycle of fasting, when the mice were euthanized. Adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), CC BY 4.0. g, Corticosterone and progesterone levels in blood of mice before and after four cycles of TMX plus fasting (n = 9). n represents number of mice per treatment group. Data were analysed by two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test. h, Schematic representation of serum collection from patients with breast cancer who were being treated with endocrine therapy, before and after five days of FMD. Adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), CC BY 4.0. i, Cortisol and progesterone concentrations in serum of patients with ERα+ breast cancer, as described in h. Data were analysed by two-tailed Student’s paired t-test. j, Cortisol concentrations in serum of patients with ERα+ breast cancer before and after five days of FMD. Data were analysed by two-tailed Student’s paired t-test.

SHRs exert their function by binding specific genomic regions to drive expression of their target genes. ChIP–seq analyses of GR and PR showed strong chromatin interactions upon fasting (Fig. 2b,c, Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Table 1). In line with our in silico predictions and motif enrichment analyses (Fig. 1f, bottom), H3K27ac regions that were enhanced with fasting were enriched for GR and PR occupancy, both after fasting alone and after fasting with TMX (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Whereas overall JUN chromatin binding was increased in tumours from fasted mice (Extended Data Fig. 2d and Extended Data Table 1), JUN binding was not observed in the newly engaged H3K27ac sites upon dietary intervention (Fig. 2d,e). When analysing sites that lost H3K27ac, we found that JUN occupancy remained unaltered. These data imply that fasting resulted in a loss of enhancer action at AP-1 sites, without affecting AP-1 chromatin binding at these sites. For newly gained enhancers, AP-1 was found not to occupy these regions, whereas both GR and PR did.

GR and PR are SHRs that depend on their cognate ligands for activation, namely cortisol (or corticosterone in mice) and progesterone, respectively. Therefore, we measured the levels of both hormones in mouse blood before and after the four-week treatment (which included four fasting cycles) (Fig. 2f,g) and in the serum of patients with breast cancer who were undergoing endocrine therapy in combination with a five-day FMD regimen as part of a clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05748704) (n = 15) (Fig. 2h,i and Extended Data Table 2). In mice, fasting alone or fasting combined with TMX increased the concentrations of circulating corticosterone and progesterone (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 3a). Analogously, FMD also increased cortisol and progesterone levels in patients with breast cancer who were undergoing endocrine therapy (Fig. 2i), as well as in patients with breast cancer undergoing FMD without concomitant endocrine therapy in the DigesT study (n = 35; ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03454282) (Fig. 2j). Fasting and FMDs were previously found to reduce blood IGF1, insulin and leptin concentrations (hereafter collectively referred to as fasting-reduced factors (FRFs)), in mice and humans with breast cancer3,6,21,22. The re-introduction of these FRFs reduced the beneficial effects of fasting on tumour growth3 (Extended Data Fig. 3b) and prevented the increase of circulating corticosterone and progesterone levels in mice treated with TMX plus fasting (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

Collectively, these results indicate that fasting (in mice) and a FMD (in patients) increase the blood levels of cortisol and progesterone, promoting GR and PR activation in HR+ breast cancer cells. Furthermore, fasting switches AP-1 occupied sites from an active epigenetic state to a repressed chromatin state, without affecting AP-1 binding.

Fasting activates GR-responsive genes

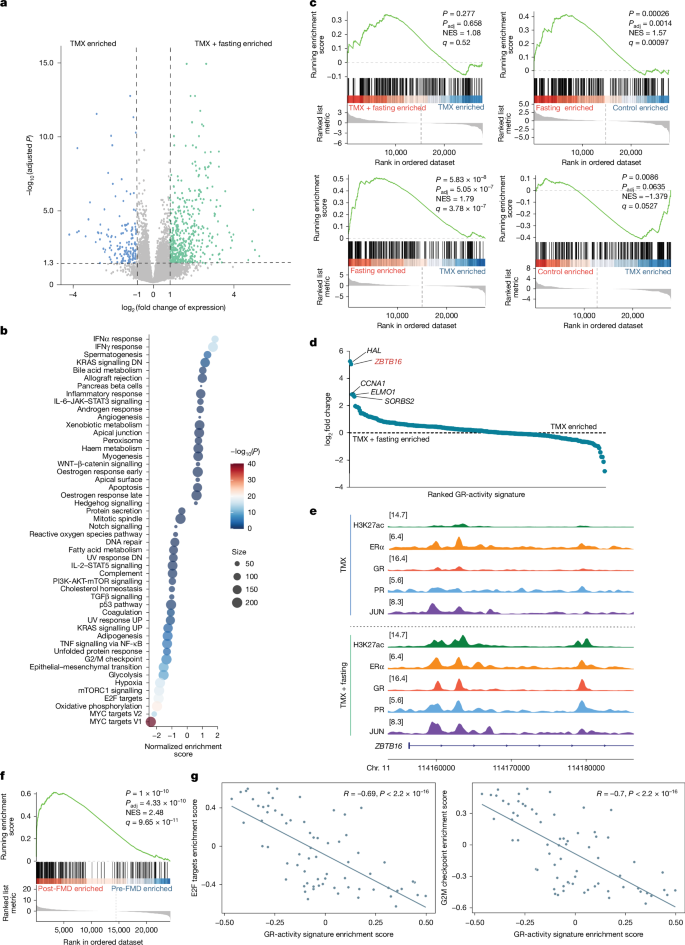

To understand the transcriptional consequences of an altered epigenome upon fasting, and whether and how such changes contribute to enhance endocrine therapy anti-tumour activity, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses. Consistent with the observed tumour regressions (Fig. 1b), RNA-seq analysis of MCF7 xenografts that were treated with TMX plus fasting revealed an inhibition of pathways related to cell proliferation (MYC23 and E2F targets24) (Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). In agreement with our previous study3, the nutrient sensor25 mTOR showed decreased activity after fasting (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 3d). These data were confirmed by proteomic analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3e,f). Since fasting increased corticosteroid levels in mice and patients with HR+ breast cancer (Fig. 2g,i,j) and increased chromatin binding of GR (Fig. 2b,c and Extended Data Fig. 2c), we utilized a pan-cancer applicable GR-activity gene signature16 that confirmed elevated GR transcriptional activity in tumours collected from mice treated with TMX plus fasting (Fig. 3c). Unexpectedly, TMX treatment alone significantly reduced the expression of the GR-activity signature (Fig. 3c). GR activation was recently reported to exert anti-tumour effects in breast cancer by increasing the expression of the transcriptional suppressor ZBTB16 (also known as PLZF)16. Of note, ZBTB16 was the second most upregulated GR-signature gene in mice that received both TMX and weekly fasting cycles (Fig. 3d). Consistent with these findings, increased chromatin occupancy of both GR and PR was observed at the ZBTB16 gene locus after fasting, which was accompanied by a marked increase in the active enhancer–promoter marker H3K27ac at the same site (Fig. 3e).

a, Volcano plot depicting genes that are differentially expressed between TMX and TMX plus fasting treated MCF7 xenografts. Differential gene expression was determined by two-sided Wald test. b, Gene set enrichment analysis for Hallmark pathways. Shown are the pathways that are differentially enriched upon treatment with TMX or TMX plus fasting. Normalized enrichment score (NES) was calculated by weighted Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and P value was determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini–Hochberg hypothesis correction. DN, downregulation; UP, upregulation. c, Enrichment plot of a pan-cancer GR-activity signature for all depicted conditions. NES was calculated by weighted Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and P value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini–Hochberg hypothesis correction. d, Differential expression analyses for GR-activity signature genes, based on log2-transformed fold change ranking, comparing TMX and TMX plus fasting conditions. e, Snapshots of H3K27ac, ERα, GR, PR and JUN ChIP–seq signal at the ZBTB16 gene locus in TMX-treated and TMX plus fasting-treated xenografts. f, Enrichment plot for GR-activity signature in matched tumour samples of patients with breast cancer, before and after five days of FMD. NES was calculated by weighted Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and P value was determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini–Hochberg hypothesis correction. g, Correlation plot between of G2M and E2F Hallmarks, and the GR-activity signature in matched tumour samples from patients with breast cancer, before and after five days of FMD. Two-sided Spearman’s linear correlation between gene set variation analysis (GSVA) enrichment scores of the indicated gene sets was calculated, and R and P values are shown.

To confirm our xenograft-based observations in patients with breast cancer, we applied the same GR-activity signature to transcriptomic data derived from matched tumours specimens (pre- and post-FMD) from patients with HR+ breast cancer undergoing a five-day FMD in the clinical trial NCT03454282. Consistent with the data obtained in mice, GR transcriptional activity was increased after FMD in these patient samples (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). Moreover, we found that GR activity was negatively correlated with two Hallmark gene sets of tumour proliferation (Hallmark of E2F targets and G2M Checkpoint) (Fig. 3g). In line with the increased PR chromatin binding (Fig. 2b,c, Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Table 1) and the increased progesterone levels (Fig. 2g,i and Extended Data Fig. 3a), PR transcriptional activity was also increased in patients after FMD (Extended Data Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Table 3).

Overall, these results indicate that fasting selectively activates transcriptional programmes that are under the control of GR and PR, both of which are known for their tumour suppressor function in HR+ breast cancer16,17.

GR activation mimics fasting effects

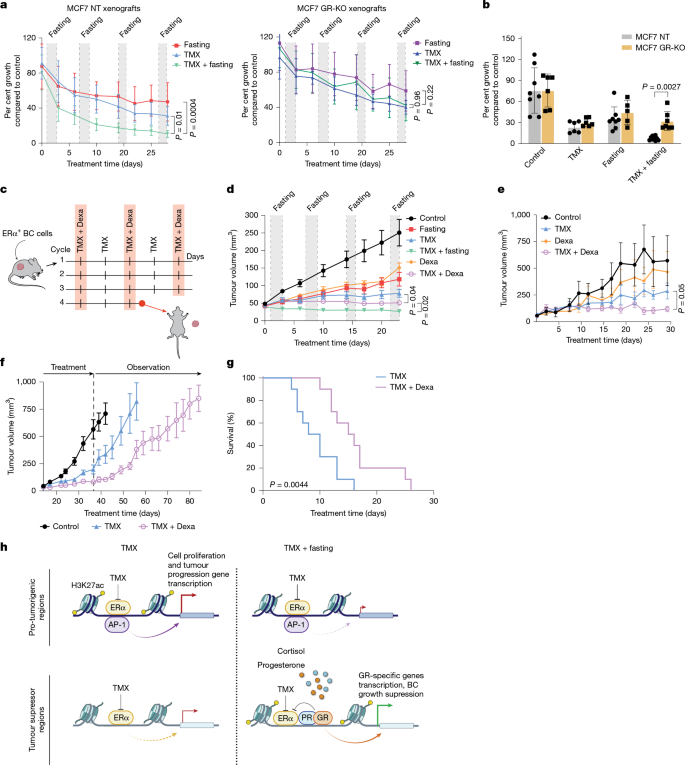

The beneficial effects of PR activation in HR+ breast cancer have previously been reported17 and are being explored in the phase 2 clinical trial PIONEER (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03306472). However, the role of GR activation in this type of cancer remains poorly understood. Here we focus on GR and its role in the enhancement of endocrine therapy activity through fasting. To determine whether the anti-proliferative effects of fasting are critically mediated by GR action, we knocked out GR in MCF7 cells (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b) and generated mouse xenografts from these GR-knockout (GR-KO) cells. As expected, GR-KO MCF7 cells did not respond to the GR agonist dexamethasone (Dexa) (Extended Data Fig. 5c–f). GR-KO and control MCF7 mouse xenografts were exposed to weekly 48 h fasting cycles, with or without TMX treatment (treatment schedule as in Fig. 1a). Whereas in control tumours, TMX and fasting synergistically blocked tumour growth (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Fig. 6a,b), confirming our previous observation3 (Fig. 1b), this synergy was lost when GR was knocked out (Fig. 4a,b and Extended Data Fig. 6c,d).

a, Non-targeted control (NT) or GR-KO MCF7 xenograft tumour growth in six-to-eight-week-old female athymic nude mice treated with fasting (NT, n = 8; GR-KO, n = 6), TMX (NT, n = 9; GR-KO, n = 7) and TMX plus fasting (NT, n = 11; GR-KO, n = 9). Tumour growth was normalized to the respective control tumours b, Per cent MCF7 NT or GR-KO tumour volume compared with the respective control (control: NT, n = 8; GR-KO, n = 6; fasting: NT, n = 8; GR-KO, n = 5; TMX: NT, n = 6; GR-KO, n = 6; TMX plus fasting: NT, n = 10; GR-KO, n = 7). Data are mean ± s.d. Comparison by two-sided Student’s t-test on the last day. c, Schematic representation of the four treatment cycles. Mice were randomized into control arm, Dexa, TMX or TMX plus Dexa treatment arms. BC, breast cancer. Adapted from Servier Medical Art (https://smart.servier.com), CC BY 4.0. d, MCF7 xenograft outgrowth in six-to-eight-week-old female athymic nude mice in the different treatment arms (control, n = 8; TMX, n = 9; Dexa, n = 6; fasting, n = 8; TMX plus fasting, n = 11; TMX plus Dexa, n = 7). e, HR+ breast cancer PDX outgrowth in six-to-eight-week-old female NSG mice in the different treatment arms (control, n = 4; TMX, n = 4; Dexa, n = 4; TMX plus Dexa, n = 5). f, MCF7 xenograft outgrowth in six-to-eight-week-old female athymic nude mice in the different treatment arms (control, n = 7; TMX, n = 7; Dexa, n = 5; TMX plus Dexa, n = 6). After four weeks, all treatments were stopped and tumours were allowed to re-grow. Data are mean ± s.e.m. g. Survival curves of immunocompetent mice engrafted with TSAE1 cells and treated with either TMX alone (n = 10) or combined with Dexa (n = 10). Log-rank test is depicted. h. Proposed model for fasting-enhanced TMX response in breast cancer cells. a,b,d–g, n, number of tumours per treatment group. a,d,e, Data are mean ± s.e.m. P values by mixed-effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (Supplementary Information) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P values of last day are represented).

Since GR appeared to have a central role in fasting-mediated enhancement of endocrine therapy for HR+ breast cancer, we hypothesized that the beneficial effects of fasting could be mimicked by glucocorticoid administration. To test this hypothesis, we compared the anti-tumour activity of Dexa with fasting, alone or in combination with TMX, in MCF7 xenografts (Fig. 4c). Notably, combined Dexa and TMX phenocopied the anti-tumour activity of fasting plus TMX (Fig. 4d). Mice treated with Dexa did not undergo weight changes, whereas weight loss was observed in fasted mice (Extended Data Fig. 6e). The ability of Dexa to enhance endocrine therapy activity was further validated in a second HR+ breast cancer xenograft model (T47D; Extended Data Fig. 6f,g) and in a HR+ patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model (IDC186; Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 6h,i). Consistent with the ability of combined fasting plus endocrine therapy to exert carry-over anti-tumour activity, we found that one month of treatment of MCF7 xenograft-bearing mice with Dexa plus TMX delayed tumour growth, after treatment withdrawal, by a factor of two, compared with fasting or TMX alone (Fig. 4f and Extended Data Fig. 7a).

We previously reported that fasting and FMDs lower insulin, IGF1 and leptin plasma concentrations in mice and humans with breast cancer3,6,21,22. Thus, we assessed whether the ability of Dexa to phenocopy the anti-tumour activity of fasting would reflect similar effects on these FRFs. Leptin and c-peptide were not affected, whereas serum IGF1 concentration decreased in response to Dexa (Extended Data Fig. 7b). Finally, in mice that were treated with TMX, Dexa attenuated TMX-induced uterus hyperplasia, a relatively common side effect of TMX, which we previously reported to be effectively prevented by fasting3 (Extended Data Fig. 7c).

Dexamethasone is a potent immunomodulator, with significant adverse effects when chronically administered26. Therefore, we next determined whether the combined effect of Dexa and TMX might be less effective or even detrimental in an immunocompetent HR+ breast cancer model, by affecting anti-tumour immunity. In allografts of the ERα+ TSAE1 mouse breast cancer cell line27,28 in BALB/c mice, combined treatment of Dexa with TMX significantly reduced tumour growth (Extended Data Fig. 7e,f) and increased the survival of these mice compared with TMX treatment alone (Fig. 4g).

To better understand whether and how treatment with Dexa would modulate the peripheral immune landscape, particularly with respect to the effects specific for TMX, we performed immune profiling of BALB/c mice bearing TSAE1 tumours from the different treatment groups (control, TMX, Dexa and TMX plus Dexa). We found no overt changes in leukocyte populations and in their proliferative capacities in response to the different treatments. However, combined Dexa plus TMX treatment led to a significant reduction in PD-L1 expression in neutrophils, non-classical monocytes and dendritic cells as compared with control treatment (Extended Data Fig. 7f).

Cumulatively, our findings indicate that the beneficial effects of fasting in enhancing endocrine therapy efficacy in breast cancer are mediated through GR activation, and that corticosteroid administration can be used to replace fasting to increase endocrine therapy activity.

Discussion

Dietary restriction represents a timely and promising research field in oncology. In particular, fasting or FMD regimens hold promise to achieve strong anti-tumour effects, with the ability to simultaneously activate multiple anti-tumour mechanisms3. Yet, concerns about the risk of malnutrition and impact on quality of life in relation to these diets remain. Thus, the search for fasting mimetics that could recreate its benefit in terms of anticancer effects is warranted. Our study defines GR agonists, such as Dexa, as a therapeutic intervention that phenocopies the beneficial effects of fasting, enhancing endocrine therapy efficacy. GR agonists have been used in the clinic for decades, including as anticancer agents (for example, for haematological malignancies such as lymphomas or multiple myeloma), anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic drugs, and antiemetics. However, their prescription as drugs that can modify the activity of endocrine therapy for HR+ breast cancer in currently not foreseen.

Fasting has direct metabolic consequences, such as lower serum glucose, decreased insulin levels and, consequently, decreased AKT–mTOR signalling, which have been attributed anti-tumour effects3, including in breast cancer. Our data show that the ability of fasting to enhance the anti-tumour effects of endocrine therapy for breast cancer is largely mediated through GR signalling. SHRs show substantial genomic crosstalk in breast cancer cells. In particular, GR, AR and PR all share genomic regions with ERα throughout the genome29 and serve as tumour suppressors in HR+ breast cancer16,17,18. Although the crosstalk between SHRs has been studied extensively at the biological level, suggesting novel therapeutic opportunities in breast cancer treatment17, the physiological causes of this interplay remain unknown. We show here that fasting increases levels of cortisol (or corticosterone) and progesterone, selectively activating GR and PR genetic programmes, to increase the effect of endocrine therapy in breast cancer (Fig. 4h).

PR agonist treatment is being evaluated in combination with letrozole in a phase 2 randomized clinical trial in patients with ERα+ breast cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03306472). However, the MIPRA clinical trial showed that PR inhibition by mifepristone also reduced tumour cell proliferation in patients with HR+ breast cancer (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02651844)30. These contradictory results can be partially explained by the use of mifepristone, which is a potent PR inhibitor but, when used at high doses or depending on the time of the day when the drug is taken (night versus morning), also acts as a GR agonist31,32,33. GR activation promotes a luminal HR+ breast cancer phenotype associated with improved prognosis and reduced cell proliferation16. Here we show that GR activation enhances the effects of the endocrine therapy, and exogenously administered GR agonists phenocopy the favourable effects of fasting.

Chronic treatment with corticosteroids may exert undesirable effects on the immune system, bones, muscles and endocrine system26. Our in vivo studies using an immunocompetent mice model revealed that Dexa significantly delayed tumour growth and extended survival of mice bearing an HR+ tumour compared with TMX alone (Fig. 4g). Moreover, immune profiling of these mice indicated a balanced immune state, with no signs of pronounced activation or suppression. We observed a significant reduction in PD-L1 expression in some immune cell populations when Dexa was combined with TMX (Extended Data Fig. 7f). Since low PD-L1 expression is considered to be a marker of immune cell activation and increased anticancer activity of the immune system34, it is possible that the anti-tumour effects that we observed with TMX plus Dexa in this immunocompetent mouse breast cancer model also reflected favourable systemic effects of Dexa on anti-tumour immunity, although this mechanism needs to be confirmed through further studies.

GR stimulation is most effective at decreasing breast cancer cell proliferation in the luminal A patient population16, which is consistent with our data. Several clinical trials from the late 1980s and early 1990s evaluated the therapeutic contribution of glucocorticoids to endocrine therapy in patients with breast cancer, finding that the glucocorticoids only modestly improved response rates35,36,37. However, these clinical trials enrolled patients with unknown receptor status. Since GR agonism drives tumour migration and proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer38, the limited benefit of glucocorticoid administration in the earlier studies may be explained by the enrollment of a significant fraction of patients with triple-negative breast cancer35,36,37.

Our study positions glucocorticoid administration as a novel therapeutic strategy that mimics the effects of fasting in HR+ breast cancer cancer treatment, substituting the need for dietary restriction with a clinically approved and safe therapeutic agent.

Methods

Animal experiments

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal care and use established in the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (directive 86/609/EEC). Animal work was only initiated upon approval by the Italian Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) with authorization no. 40/2022, protocol 22418.167 or by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Netherlands Cancer Institute. Six-to-eight-week-old female athymic nude mice (purchased from Envigo) were used in the experiments at the Animal Facility of the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Genoa). These mice were housed in Sealsafe Plus GM500 individually ventilated cages (IVCs) held on DGM Racks at 22 ± 2 °C and approximately 50–60% relative humidity under a 12 h:12 h light:dark lighting cycle and with food (standard diet, 4RF18, Mucedola) and water ad libitum. Mice were acclimatized for one week before experiments were initiated. To allow MCF7 xenograft growth, a 17β-oestradiol-releasing pellet (Innovative Research of America) was inserted in the intra-scapular subcutaneous region under anaesthesia conditions, the day before cell injection. Xenografts were established by subcutaneous injection of 5 × 106 MCF7 cells to both flanks of the mouse (experiments in Figs. 1a,b, 2 and 4a,b), or orthotopic injection of 3 × 106 MCF7 cells into the fourth abdominal fat pad (experiments in Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). Treatment was initiated when the tumours appeared as established palpable masses (~2 weeks after cell injection). In each experiment, mice were randomly assigned to receive one of the following treatments or their combinations, as indicated: control (ad libitum diet); TMX (45 mg kg−1 per day in peanut oil, oral gavage3,39), fasting (water only, for 48 h every week3,40), Dexa (4 mg kg−1 every other day in physiological solution, intraperitoneal41), IGF1 (200 μg kg−1 body weight, intraperitoneal twice a day on the days of fasting); insulin (20 mU kg−1 body weight, intraperitoneal once a day on the days of fasting); leptin (1 mg kg−1 body weight, intraperitoneal once a day on the day of fasting). During the 48 h of fasting, mice were individually housed in a clean, new cage to reduce coprophagy and the intake of the residual chow. Body weight was measured immediately before, during and after fasting. Fasting cycles were repeated every seven days to allow for complete recovery of body weight before a new cycle. The size of the tumours was measured twice a week and tumour volume was calculated using the formula: tumour volume (in mm3) = (w2 × W) × π/6, where w and W are lengths of the minor side and major side (in mm), respectively. The maximum tumour volume that was permitted by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) was 1,500 mm3, and in none of the experiments were these limits exceeded. Tumour masses were isolated at the end of the last fasting cycle, weighed, divided into two parts, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Ten slices of 50 μm per tumour sample were subsequently utilized for ChIP–seq, proteomics and RNA-seq analyses. Sample size estimation was performed using PS (power and sample size calculation) software (Vanderbilt University). By this approach, we estimated that the number of mice that were assigned to each treatment group would reach a power of 0.85. The type I error probability associated with our tests of the null hypothesis was 0.05. Mice were assigned to the different experimental groups in a random fashion. Operators were unblinded, as blinding during animal experiments was not possible because mice were subject to a specific diet supply and daily treatment.

To establish mammary intraductal cell line-derived xenograft (MIND-CDX) models, T47D cells were intraductally injected as previously described39,42. Specifically, 1 × 106 T47D cells were dissociated to single cells with 0.05% trypsin and injected intraductally into the abdominal/inguinal mammary glands (both sides) of 8-week-old female NSG mice (Jackson Laboratory) with a 34G needle. To ensure stable outgrowth, T47D MIND-CDX mice were supplemented with 17β-oestradiol (Sigma, E2758) via the drinking water at a concentration of 4 µg ml−1 starting 7 days prior to tumour inoculation via intraductal injection. E2 supplementation was maintained throughout the experiment. To establish TSAE1 allograft models, BALB/c mice (Jackson Laboratory) were intraductally injected with of 1 × 104 single cells in PBS as described above (one gland). The IDC186 MIND-PDX model was established from a pre-menopausal Caucasian breast cancer patient, confirmed positive for ERα (95%) and PR (95%) but negative for HER2 (Extended Data Fig. 6h). To generate the PDX model, 5 × 104 single cells in PBS were intraductally injected into one of the abdominal mammary glands of 8-week-old female NSG mice (Jackson Laboratory) and supplemented with 17β-oestradiol (Sigma, E2758) as described above.

The xenograft model cohorts were monitored three times per week and tumours were palpated and measured via calliper in two dimensions. Mice were enrolled into treatment groups when the largest tumour per animal measured 50 mm3 for T47D and IDC186 xenografts and 25 mm3 for TSAE1 allografts, respectively. Mice were randomly allocated into treatment groups and received the following treatments: (1) vehicle treatment (corn oil, daily, oral gavage); (2) TMX (45 mg kg−1 in corn oil, daily, oral gavage); (3) Dexa (4 mg kg−1, 3 times per week, intraperitoneal injection); or (4) TMX plus Dexa. Mice were treated for 28 consecutive days for the TSAE1 and IDC186, 56 days for T47D (with a 1-week treatment break between days 28 and 35), or until the cumulative mammary tumour burden reached a volume of 1,500 mm3 and thus the maximally permitted disease end point. At euthanasia, mammary glands and full female reproductive tracts were collected in formalin, stained against haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) according to routine procedures, and uteri were analysed for histopathological abnormalities. Tumour measurements and post-mortem analysis were performed in blinded fashion. H&E slides were reviewed by a trained pathologist (J.-Y.S.) in a blinded manner. Slides were digitally processed using a PANNORAMIC 1000 whole slide scanner (3DHISTECH) and captured with the Slidescore software (www.slidescore.com).

Clinical studies of FMD in patients undergoing endocrine therapy for HR+ breast cancer

The NCT05748704 trial was conducted at the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino (Genoa), between December 2022 and February 2024 and was approved by the Comitato Etico Regione Liguria. This trial consists of a single-arm phase I/II clinical study of a FMD with solid tumours who are candidates to receive active medical or radiotherapy treatment (or with medical treatment or radiotherapy already ongoing). The nutritional intervention consists of a low-calorie diet lasting 5 days and aimed at providing between 800 and 1,000 kcal day−1 (tentatively 10% carbohydrates, 15% proteins and 75% lipids). Throughout the clinical study, patients have received dietary counselling for the intervals between FMD cycles, aiming at providing an appropriate intake of proteins, essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals43 and have also been invited to perform light/ or moderate daily muscle training to enhance muscle anabolism44. Study primary outcomes were the effects of the FMD regimen on the circulating levels of factors with pro- or anti-oncogenic activity (including insulin, IGF1, IGFBP1, IGFBP3, leptin, adiponectin, IL-6, TNF and IL-1β), as well as the effect of FMD cycles on leukocyte subpopulations with a role in tumour growth control, such as regulatory T cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) as well as natural killer (NK) cells, and its stem cell pool (for example, haematopoietic stem cells, endothelial stem cells, mesenchymal stem cells). Additional information on this trial is available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05748704. Patient serum for subsequent ELISA assays of circulating growth factors and adipokines has been routinely collected before and after the first, sixth and twelfth FMD cycle. Informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the clinical trial.

The DigesT study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03454282) trial was conducted between July 2018 and December 2020 and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the principles of Good Clinical Practice. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Ethics Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori Milan (INT 157/17). All patients provided written informed consent before any study procedures, as well as for the use of clinical and biological data for research purpose. The FMD nutritional intervention consisted in a 5-day, plant-based, calorie-restricted (up to 600 kcal on day 1; up to 300 kcal on days 2, 3, 4 and 5), low-carbohydrate, low-protein, nutritional regimen, as previously published6. Enrolled patients initiated the FMD 12–15 days before surgery, and underwent blood sampling after at least 8 h complete fasting on the morning (08:30 to 10:00) of FMD initiation (pre-FMD), and on the morning of FMD completion (post-FMD). Tumour samples for RNA-seq analyses were obtained diagnostic core biopsies performed at baseline (Pre-) and from matched surgical specimens (Post-). The primary outcomes of the study were to measure the absolute and relative changes in population of peripheral blood mononuclear cells before and after the FMD. Additional information on this trial is available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03454282.

ChIP–seq

Snap-frozen xenografted tumours were double fixed using 2 mM of disuccinimidyl glutarate diluted in solution A (50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA) for 25 min followed by 1% formaldehyde for 20 min, at room temperature. Cells were then lysed and sonicated accordingly to the protocol previously described45, with the difference of have performed 15 cycles of 30 s on, 30 s off in the sonication step (BioRuptor Pico, Diagenode). Obtained nuclear lysates were incubated overnight with 50 μl of protein A coated Dynabeads magnetic beads (10008D, Invitrogen) conjugated with 5 μg of ERα (06-935, Millipore), H3K27ac (39133, Active Motif), GR (12041S, Cell Signaling), PR (8757S, Cell Signaling) or JUN (9165S, Cell Signaling) antibodies. The resulting immunoprecipitated DNA was submitted for library preparation using the KAPA library kit (KK8234, Roche) and subsequently paired-end sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system with read length of 51 bp. ChIP–seq analyses were performed using an in house pipeline publicly available at https://github.com/sebastian-gregoricchio/ChIP_Zwart (v.0.1.2) with default parameters. In brief, all samples were aligned to reference genome Hg38/GRCh38 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner46 (BWA v.0.5.10). Reads were filtered based on mapping quality (MAPQ ≥ 20), and duplicate reads were marked with Picard MarkDuplicates (v.2.19.0). MACS2 (v.2.1.2) was used to perform peak calling over input ChIP–seq samples; only peaks with a q-value < 0.01 were retained. DeepTools47 (v.2.5.3) was used to calculate the fraction of reads in peaks (FRiP) and normalized ChIP–seq signal. For visualization purposes, Reads Per Genomic Content (RPGC) normalization (1× coverage) signal was averaged among the replicates per each condition using deeptools bigwigCompare. Genome browser snapshots were generated using the R v.4.0.3 environment and Rseb48 (v.0.3.1) (https://github.com/sebastian-gregoricchio/Rseb). Tornado plots were generated using deepTools (v.2.5.3). Differential peak analyses were performed using diffBind49 (v.3.0.15). Peaks were defined as differential when the |log2(fold change)| >1.5 and adjusted P value <0.05. Genomic location annotation of the peaks was performed using ChIPSeeker50 (v.1.26.2) defining the promoter region as −2 kb:transcription start site:+1 kb. Transcription factor binding enrichment from public available datasets—GIGGLE analyses51—were performed using the tool available at the of CistromeDB website (http://cistrome.org/db/).

Cell lines

The MCF7, T47D and HEK293T cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). TSAE1 cells were a gift from C. Isacke laboratory28. All cell lines were kept in DMEM, high glucose, pyruvate (Gibco) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Capricorn Scientific) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (5,000 U ml−1, Life Technologies). For ligand treatment, 4-hydroxytamoxifen (HY16950; MedChemExpress) and SR11302 (HY-15870; MedChemExpress) were reconstituted in DMSO, and used in the described concentrations and time points. All cell lines were cultured at 5% CO2 at 37 °C, were subjected to regular Mycoplasma testing, and underwent authentication by short tandem repeat profiling (Eurofins Genomics).

CRISPR–Cas9-mediated knockout cell line generation

GR-targeting single-guide RNA (NR3C1; ATGACTACGCTCAACATGTT) and non-targeting (NT) control guide RNA (GTATTACTGATATTGGTGGG) were separately cloned into the lentiCRISPR v.2 vector52. Using H3K293T cells, the CRISPR vectors were co-transfected with third-generation viral vectors using polyethyleneimine (PEI, Polysciences). After lentivirus production, the medium was collected and added to the MCF7 cells. Two days after infection, cells were selected for 2 weeks with 2 μg ml−1 puromycin (Sigma Aldrich), and knockout efficiency was confirmed by western blot and immunofluorescence.

Immunoblotting

Total protein lysates were obtained using Laemmli buffer complemented with 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and 1× phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Forty micrograms of protein per sample was resolved in a NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (NP0335BOX, Invitrogen) in 1× NuPAGE MOPS SDS Running Buffer (NP00012, Invitrogen) and sequentially transferred to a 0.45-μm nitrocellulose membrane (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Protein detection was performed using antibodies raised to detect GR (1:1,000, 12041S, Cell Signaling) and β-actin (1:10,000, MAB1501R, Merck Millipore). Odyssey CLx Imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences) and ImageStudio Lite v.5.2.5 (LI-COR Biosciences) software were used to scan and visualize the proteins.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (103999, Merck) for 10 min, washed twice with PBS and subsequently permeabilized with 0.5% Triton/PBS (Triton X-100, Sigma Aldrich). Following two PBS washing steps, cells were blocked for 1 h in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, A8022, Sigma/Merck)/PBS solution before incubation with antibody against GR (1:100, 12041S, Cell Signaling). After two additional PBS washes, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000, A-11008, ThermoFisher Scientific) and DAPI (ProLong Gold Antifade Mountant, P36930, ThermoFisher Scientific) and signal detected using laser confocal microscopy (SP5, Leica).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry of the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumour samples was performed on a BenchMark Ultra (Ki-67) or a Discovery Ultra (ERα, PR, GR) automated stainer (Ventana Medical Systems). In brief, paraffin sections were cut at 3 µm, heated at 75 °C for 28 min and deparaffinised in the instrument with EZ prep solution (Ventana Medical Systems). Heat-induced antigen retrieval was carried out using Cell Conditioning 1 (CC1, Ventana Medical Systems) for 32 min (Ki-67, ERα, PR) or 64 min (GR) at 95 °C. Ki-67 was detected using the clone 30-9 (Ready-to-Use, 32 min at 37 °C, Roche Diagnostics/Ventana), GR using the clone D6H2L (1/600 dilution, 1 h at 37 °C, 12041, Cell Signalling), ERα using the clone SP1 (Ready-to-Use, 32 min at room temperature, Roche Diagnostics/Ventana) and PR using the clone 1E2 (Ready-to-Use, 32 min at room temperature, Roche Diagnostics/Ventana). In order to reduce background signal for the PR staining, after primary antibody incubation slides were incubated with normal antibody diluent (Roche Diagnostics) for 24 min. Bound Ki-67 antibody was detected using the OptiView DAB Detection Kit (Ventana Medical Systems). GR and ERα bound antibody was visualized using Anti-Rabbit HQ (Ventana Medical systems) for 12 min at 37 °C followed by Anti-HQ HRP (Ventana Medical systems) for 12 min at 37 °C and the ChromoMap DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems). PR bound antibody was detected using OmniMap anti-Rabbit HRP (Ventana Medical systems) for 12 min at room temperature. followed by ChromoMap DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems). Slides were counterstained with Hematoxylin and Bluing Reagent (Ventana Medical Systems). A PANNORAMIC 1000 scanner from 3DHISTECH was used to scan the slides at a 40× magnification and uploaded to the Slidescore software (www.slidescore.com). Digitized slides were further processed using QuPath (v.0.6.0)53. The analysis protocol begins with tissue detection using a pixel classifier, which differentiates foreground from background (white) pixels. Next, manual annotation is performed with the brush tool to delineate and exclude stroma areas from the region of interest. To identify Ki-67-positive and negative cells, the native cell detection tool is used with the optical density sum option for image analysis. Default parameters are applied, with adjustments made only to the pixel size (0.25 µm), based on the slide resolution, and the target cell size (8 µm) for accurate cell identification. Finally, the scoring is calculated as the proportion of positive cells relative to the total number of detected cells, providing a quantitative assessment of Ki-67 expression. All quantifications were compared and approved by a trained pathologist (J.S.).

RNA-seq analyses

MCF7 xenograft tumour RNA was isolated by homogenizing the tissue sample in 1 ml of RLT buffer (79216, Qiagen) and 1% β-mercaptoethanol using the Qiagen TissueLyserII (85300, Qiagen) for 6 min with frequency setting 30 (1 s−1) in combination with 5-mm stainless steel beads (69989, Qiagen). The total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (74106, Qiagen), including an on column Dnase digestion (79254, Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Rneasy Mini Handbook, Qiagen). Quality and quantity of the total RNA was assessed by the 2100 Bioanalyzer using a Nano chip (Agilent). Total RNA samples having RNA integrity number (RIN) >8 were subjected to library generation. Strand-specific libraries were generated using the TruSeq Stranded mRNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, RS-122-2101/2) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, document 1000000040498 v.00). In brief, polyadenylated RNA from intact total RNA was purified using oligo-dT beads. Following purification the RNA was fragmented, random primed and reverse transcribed using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, 18064-014) with the addition of actinomycin D. Second strand synthesis was performed using polymerase I and RnaseH with replacement of dTTP for dUTP. The generated cDNA fragments were 3′ end adenylated and ligated to IDT xGen UDI(10 bp)-UMI(9 bp) paired-end sequencing adapters (Integrated DNA Technologies) and subsequently amplified by 12 cycles of PCR. The libraries were analysed on a 2100 Bioanalyzer using a 7500 chip (Agilent), diluted and pooled equimolar into a multiplex sequencing pool. The libraries were sequenced with 51 paired-end reads on a NovaSeq 6000 using a Reagent Kit v.1.5 (100cycles) (Illumina). After sequencing, data was aligned to the human reference genome Hg38/GRCh38 using HISAT254 (v.2.1.0) and the number of reads per gene were calculated using HTSeq count55 (v.0.5.3). Gene expression differences, between the conditions, were determined using DESeq256 (v.1.22.2) with |log2(fold change)| > 1 and adjusted P value <0.05 cut-offs. Differentially expressed genes were ranked by log2(fold change expression) and used for gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) on the Hallmark gene set from msigdbr (v.7.5.1), a previously published GR-activity signature16 or a newly developed PR-activity signature17 (Extended Data Table 3), using clusterProfiler57 (v.3.18.1), (pvalueCutoff = 0.05, pAdjustMethod = “BH”). GSEA enrichment plots have been generated using the plot.gsea function from the Rseb package48 (v.0.3.2).

Tumour RNA was extracted from FFPE tumour specimens from patients with breast cancer using the MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (Lucigen, LGC Biosearch Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality was evaluated using Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies) on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). RNA-seq libraries were prepared using TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Prep Gold (20020598, Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and sequenced using 50 bp paired-end sequencing mode on Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina). Differential gene expression analysis comparing Post- versus Pre- samples was performed using negative binomial distribution and Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) with the Bioconductor package DESeq2, applying Wald tests on normalized counts to obtain log2(fold change) and P values for each gene. To evaluate the activity of pathways of interest (GR-activity signature and PR-activity signature16,17 (Extended Data Table 3) and Hallmark gene sets) we performed GSEA using the Bioconductor package clusterProfiler. GSEA was performed on genes ranked by the absolute value of log10(P value) scaled by the sign of log2(fold change), tested against gene lists of interest. The enrichment score and NES were computed for each gene set, and nominal P values were estimated by permutation testing. Multiple testing correction was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to obtain FDR q values. To estimate the activity of pathways of interest at a single sample level we performed GSVA. Differences in enrichment scores between Post- and Pre- samples were determined by the paired Wilcoxon test. To correlate the activity of GR-activity signature and Hallmark gene sets of interest, their GSVA enrichment scores were correlated through Spearman’s linear correlation. All analyses were performed with R studio software (v.2023.03).

Proteomics

For protein digestion, frozen tissues were lysed in boiling guanidine HCl (GuHCl) lysis buffer as previously described58. Protein concentration was determined with a Pierce Coomassie (Bradford) Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After dilution to 2 M GuHCl, aliquots corresponding to at least 1.05 mg of protein were digested twice (4 h and overnight) with trypsin (Sigma Aldrich) at 37 °C, enzyme:substrate ratio 1:75. Digestion was quenched by the addition of formic acid (final concentration 5%), after which the peptides were desalted on a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters). From the eluates, aliquots were collected for proteome analysis, the remainder being reserved for phosphoproteome analysis (not included in this work). Samples were vacuum dried and stored at −80 °C until LC–MS/MS analysis.

Prior to mass spectrometry analysis, the peptides were reconstituted in 2% formic acid. Peptide mixtures were analysed by nano LC–MS/MS on an Orbitrap Exploris 480 Mass Spectrometer equipped with an EASY-NLC 1200 system (Thermo Scientific). Samples were directly loaded onto the analytical column (ReproSil-Pur 120 C18-AQ, 2.4 μm, 75 μm × 500 mm, packed in house). Solvent A was 0.1% formic acid/water and solvent B was 0.1% formic acid/80% acetonitrile. Samples were eluted from the analytical column at a constant flow of 250 nl min−1. For single-run proteome a 90-min gradient was employed containing a 78-min linear increase from 6 to 30% solvent B, followed by a 10-min wash.

Raw data were analysed by DIA-NN (v.1.8)59 without a spectral library and with ‘Deep learning’ option enabled. The Swissprot Human database (20,395 entries, release 2021_04) was added for the library-free search. The Quantification strategy was set to Robust LC (high accuracy) and MBR option was enabled. The other settings were kept at the default values. The protein groups report from DIA-NN was used for downstream analysis in Perseus (v.1.6.15.0)60. Values were log2-transformed, after which proteins were filtered for at least 100% valid values in at least one sample group. Missing values were replaced by imputation based on a normal distribution using a width of 0.3 and a minimal downshift of 2.4. Differentially expressed proteins were determined using a Student’s t-test (threshold: FDR: 5% and S0: 0.1).

Differentially protein levels were ranked by log2(fold change) × P value and used for GSEA analysis on Hallmarks from the community-contributed functional database from the web-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit (WebGestalt61). GSEA enrichment plots were generated as previously described.

ELISA

Mouse whole blood was collected in Eppendorf tubes. It was allowed to coagulate for 2 h at room temperature, centrifuged for 20 min at 4,000 rpm, then aliquoted into PCR tubes and stored at −80 °C until subsequent use. Whole blood from patients was collected in Vacuette Serum Clot Tubes (BD), centrifuged 20 min at 2,100 rpm then aliquoted into small tubes and stored at −80 °C until use. ELISA assays to detect mouse serum levels of cortisone and progesterone were purchased from R&D System and ALPCO respectively while ELISA assays to detect human serum levels of cortisol and progesterone were purchased from R&D System and Enzo, respectively.

Flow cytometry

Breast cancer nodules were macrodissected from TSAE1-bearing mice and processed to generate single-cell suspensions using the Tumour Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, 130-096-730) in conjunction with the gentleMACS Octo Dissociator, following the manufacturers’ protocols. The resulting cell suspensions were passed through a 100-µm cell strainer and subsequently washed with fluorescence-activated cell sorting buffer (PBS containing 5% FBS). To ensure the removal of red blood cells, samples were treated with an erythrocyte lysis solution. Following this, samples were pre-incubated with an anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (1:400, 553142, BD Bioscience) and then stained with antibodies specific for extracellular markers, adhering to standard staining protocols. After staining for surface markers, cells were labelled with a live/dead viability dye and subsequently fixed and permeabilized using a fixation/permeabilization solution (eBioscience, Invitrogen) for intracellular staining. All antibodies utilized for flow cytometry were titrated to account for lot-dependent variations, as described in Extended Data Fig. 7f. Immune cell populations were classified as follows: lymphoid cells (CD45+CD11b−), myeloid cells (CD45+CD11b+), neutrophils (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G+), non-classical monocytes (CD45+CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C−) and dendritic cells (CD45+F4/80−CD11chiMHCIIhi) (for gating strategy used, see Supplementary Fig. 1). Sample acquisition was performed using a five-laser Aurora spectral flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences), and data analysis was conducted using FlowJo v.10 software.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software v.10.4.1 (GraphPad Software) or in R v.4.0.2 (R Core Team 2020, https://www.R-project.org). Paired t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to calculate changes in the majority of the analyses (unless otherwise stated) and only P values <0.05 were considered significant. Two-tailed Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare cortisol plasmatic concentration measured before FMD (Pre-FMD) and after FMD (Post-FMD). For the animal experiments, a linear mixed-effects model was utilized to assess whether the mass volume exhibits a statistically significant trend relative to the treatment over time. The model was constructed using the two-way ANOVA or mixed-effect model (in case of missing data) from GraphPad Prism software v.10.4.1. The fixed-effects model matrix was generated by the interaction of time (measured in days after injection) and treatment. The random-effects term was specified as the interaction between the treatment group and the blocking factor of the mouse ID. Subsequent pairwise post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted using the same software. Statistical significance was determined by P values less than 0.05. Linear mixed-effect model results are presented in the Supplementary Information.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All mouse data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files). The ChIP–seq and RNA-seq data relative to mice xenografts have been deposited to the GEO database (GSE260486). The ChIP–seq pipeline is publically accessible62. RNA-seq data for patients with breast cancer are deposited on the European Genome-Phenome Archive (EGA) under accession number EGAS00001004944. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE63 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD049477. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Burstein, H. J. Systemic therapy for estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 2557–2570 (2020).

Pan, H. et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 Years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1836–1846 (2017).

Caffa, I. et al. Fasting-mimicking diet and hormone therapy induce breast cancer regression. Nature 583, 620–624 (2020).

Koppold, D. A. et al. International consensus on fasting terminology. Cell Metab. 36, 1779–1794.e1774 (2024).

Valdemarin, F. et al. Safety and feasibility of fasting-mimicking diet and effects on nutritional status and circulating metabolic and inflammatory factors in cancer patients undergoing active treatment. Cancers 13, 4013 (2021).

Vernieri, C. et al. Fasting-mimicking diet is safe and reshapes metabolism and antitumor immunity in patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 12, 90–107 (2022).

Vernieri, C., Ligorio, F., Tripathy, D. & Longo, V. D. Cyclic fasting-mimicking diet in cancer treatment: Preclinical and clinical evidence. Cell Metab, 36, 1644–1667 (2024).

Burstein, H. J. et al. Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline focused update. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 423–438 (2018).

Creyghton, M. P. et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21931–21936 (2010).

Zheng, R. et al. Cistrome Data Browser: expanded datasets and new tools for gene regulatory analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D729–d735 (2019).

Angel, P. & Karin, M. The role of Jun, Fos and the AP-1 complex in cell-proliferation and transformation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1072, 129–157 (1991).

Shaulian, E. & Karin, M. AP-1 in cell proliferation and survival. Oncogene 20, 2390–2400 (2001).

Shen, Q. et al. The AP-1 transcription factor regulates breast cancer cell growth via cyclins and E2F factors. Oncogene 27, 366–377 (2008).

Fanjul, A. et al. A new class of retinoids with selective inhibition of AP-1 inhibits proliferation. Nature 372, 107–111 (1994).

Tonsing-Carter, E. et al. Glucocorticoid receptor modulation decreases ER-positive breast cancer cell proliferation and suppresses wild-type and mutant ER chromatin association. Breast Cancer Res. 21, 82 (2019).

Prekovic, S. et al. Luminal breast cancer identity is determined by loss of glucocorticoid receptor activity. EMBO Mol. Med. 15, e17737 (2023).

Mohammed, H. et al. Progesterone receptor modulates ERα action in breast cancer. Nature 523, 313–317 (2015).

Hickey, T. E. et al. The androgen receptor is a tumor suppressor in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Nat. Med. 27, 310–320 (2021).

Kocanova, S., Mazaheri, M., Caze-Subra, S. & Bystricky, K. Ligands specify estrogen receptor alpha nuclear localization and degradation. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 98 (2010).

Stortz, M. et al. Mapping the dynamics of the glucocorticoid receptor within the nuclear landscape. Sci. Rep. 7, 6219 (2017).

Salvadori, G. et al. Fasting-mimicking diet blocks triple-negative breast cancer and cancer stem cell escape. Cell Metab. 33, 2247–2259.e2246 (2021).

Ligorio, F. et al. Early downmodulation of tumor glycolysis predicts response to fasting-mimicking diet in triple-negative breast cancer patients. Cell Metab. 37, 330–344.e337 (2025).

Schulze, A., Oshi, M., Endo, I. & Takabe, K. MYC targets scores are associated with cancer aggressiveness and poor survival in ER-positive primary and metastatic breast cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 8127 (2020).

Oshi, M. et al. The E2F pathway score as a predictive biomarker of response to neoadjuvant therapy in ER+/HER2− breast cancer. Cells 9, 1643 (2020).

Fernandes, S. A. & Demetriades, C. The multifaceted role of nutrient sensing and mTORC1 signaling in physiology and aging. Front. Aging 2, 707372 (2021).

Buchman, A. L. Side effects of corticosteroid therapy. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 33, 289–294 (2001).

Lollini, P. L. et al. High-metastatic clones selected in vitro from a recent spontaneous BALB/c mammary adenocarcinoma cell line. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2, 251–259 (1984).

Turrell, F. K. et al. Age-associated microenvironmental changes highlight the role of PDGF-C in ER+ breast cancer metastatic relapse. Nat. Cancer 4, 468–484 (2023).

Mayayo-Peralta, I., Prekovic, S. & Zwart, W. Estrogen receptor on the move: cistromic plasticity and its implications in breast cancer. Mol. Aspects Med. 78, 100939 (2021).

Elía, A. et al. Beneficial effects of mifepristone treatment in patients with breast cancer selected by the progesterone receptor isoform ratio: results from the MIPRA trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, 866–877 (2023).

Meijer, O. C. et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-1 splice variants differentially affect corticosteroid receptor signaling. Endocrinology 146, 1438–1448 (2005).

Havel, P. J. et al. Predominately glucocorticoid agonist actions of RU-486 in young specific-pathogen-free Zucker rats. Am. J. Physiol. 271, R710–R717 (1996).

Besedovsky, L., Born, J. & Lange, T. Endogenous glucocorticoid receptor signaling drives rhythmic changes in human T-cell subset numbers and the expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. FASEB J. 28, 67–75 (2014).

Butte, M. J., Keir, M. E., Phamduy, T. B., Sharpe, A. H. & Freeman, G. J. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 27, 111–122 (2007).

Keith, B. D. Systematic review of the clinical effect of glucocorticoids on nonhematologic malignancy. BMC Cancer 8, 84 (2008).

Rubens, R. D. et al. Prednisolone improves the response to primary endocrine treatment for advanced breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 58, 626–630 (1988).

Stewart, J. F. et al. Contribution of prednisolone to the primary endocrine treatment of advanced breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 18, 1307–1314 (1982).

Obradović, M. M. S. et al. Glucocorticoids promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 567, 540–544 (2019).

Behbod, F. et al. An intraductal human-in-mouse transplantation model mimics the subtypes of ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer Res. 11, R66 (2009).

Lee, C. et al. Fasting cycles retard growth of tumors and sensitize a range of cancer cell types to chemotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 124ra127 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Administration of dexamethasone protects mice against ischemia/reperfusion induced renal injury by suppressing PI3K/AKT signaling. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 6, 2366–2375 (2013).

Lutz, C. et al. Large-scale characterization of orthotopic cell line-derived xenografts identifies TGF-β signaling as a key regulator of breast cancer morphology and aggressiveness. Cancer Res. 85, 2608–2625 (2025).

Arends, J. et al. ESPEN expert group recommendations for action against cancer-related malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. 36, 1187–1196 (2017).

Reidy, P. T. et al. Protein blend ingestion following resistance exercise promotes human muscle protein synthesis. J. Nutr. 143, 410–416 (2013).

Singh, A. A. et al. Optimized ChIP-seq method facilitates transcription factor profiling in human tumors. Life Sci. Alliance 2, e201800115 (2019).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Ramírez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–W165 (2016).

Gregoricchio, S. et al. HDAC1 and PRC2 mediate combinatorial control in SPI1/PU.1-dependent gene repression in murine erythroleukaemia. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 7938–7958 (2022).

Ross-Innes, C. S. et al. Differential oestrogen receptor binding is associated with clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nature 481, 389–393 (2012).

Yu, G., Wang, L.-G. & He, Q.-Y. ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 31, 2382–2383 (2015).

Layer, R. M. et al. GIGGLE: a search engine for large-scale integrated genome analysis. Nat. Methods 15, 123–126 (2018).

Sanjana, N. E., Shalem, O. & Zhang, F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat. Methods 11, 783–784 (2014).

Bankhead, P. et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 7, 16878 (2017).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. Omics 16, 284–287 (2012).

Jersie-Christensen, R. R., Sultan, A. & Olsen, J. V. Simple and reproducible sample preparation for single-shot phosphoproteomics with high sensitivity. Methods Mol. Biol. 1355, 251–260 (2016).

Demichev, V., Messner, C. B., Vernardis, S. I., Lilley, K. S. & Ralser, M. DIA-NN: neural networks and interference correction enable deep proteome coverage in high throughput. Nat. Methods 17, 41–44 (2020).

Tyanova, S. et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat. Methods 13, 731–740 (2016).

Elizarraras, J. M. et al. WebGestalt 2024: faster gene set analysis and new support for metabolomics and multi-omics. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, W415–W421 (2024).

Gregoricchio, S. sebastian-gregoricchio/SPACCa: v0.1.0 (0.1.0). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15309654 (2025).

Deutsch, E. W. et al. The ProteomeXchange consortium at 10 years: 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D1539–D1548 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Prekovic and the members of the Zwart/Bergman and Nencioni laboratories for valuable feedback, suggestions and input throughout the project. We acknowledge the NKI Animal facility and pathology for all the support with mouse experiments, NKI genomics core facility for the next generation sequencing and bioinformatics support, the NKI Proteomics/Mass Spectometry Facility for the proteomic and bioinformatics analyses, and the NKI-AVL Core Facility Molecular Pathology and Biobanking (CFMPB) for supplying NKI-AVL Biobank material and/or lab support. W.Z. is further supported by Dutch Cancer Society, Alpe d’HuZes and a VIDI grant (9171640) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). This work was supported in part by the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC; 22098 to A.N. and MFAG 26482 to I.C.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.N. and I.C. hold intellectual property rights on clinical uses of FMDs. C.V. and F.d.B. hold intellectual property rights on clinical uses of FMDs. F.L. reports honoraria as a speaker from Novartis, Pfizer and Accademia Nazionale di Medicina. C.V. and F.d.B. report roles in advisory boards, consultancy activity or having received honoraria as speakers from Pfizer, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Menarini Stemline, Gilead, MSD and Istituto Gentili. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Marcus Goncalves, Stephen Hursting and Eneda Toska for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Fasting reduces tumour growth and exerts epigenetic changes in ERα+ xenografts.

a. Representative immunohistochemistry stainings for Ki-67 in MCF7 xenografts from mice treated with ad-libitum diet (control, n = 6), tamoxifen (TMX, n = 5), fasting (n = 6) and combination (TMX+Fasting, n = 6). n, represents different tumour samples analysed. b. Percentage of tumour cells stained for Ki-67 in the different depicted conditions. Data are presented as mean ± SD. P-values represents one-way ANOVA with Dunnet’s multiple test correction. c. PCA plot on H3K27ac ChIP-seq data, for all 4 conditions. d. Genomic distribution of the H3K27ac ChIP-seq peaks for all 4 conditions. e. Volcano plot of the differentially-enriched H3K27ac sites between TMX and TMX+Fasting. f. H3K27ac ChIP-seq data for all 4 conditions, depicting representative regions that are differentially-enriched between TMX and TMX+Fasting. The genomic coordinates are annotated. g. Heat map showing H3K27ac ChIP-seq signal for all 4 conditions at differentially-enriched H3K27ac regions in comparing TMX or TMX+Fasting treated xenografts (top). Regions were sorted on H3K27ac signal intensity. Data are centred at H3K27ac peak, within a ± 2.5 kb window. Average density plots for ChIP-seq signal for H3K27ac in xenografts treated with the respective conditions (bottom). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. h. Cell viability of MCF7 and T47D cells treated with tamoxifen and increased concentrations of AP-1 inhibitor SR11302, alone or in combination. Data are from three biological replicates and are presented as mean ± SD. P-values represents Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn post-hoc correction. i. Heat map depicting ERα ChIP-seq signal for all 4 conditions at differentially-enriched H3K27ac regions, comparing TMX versus TMX+Fasting treated xenografts (top). Regions were sorted on ERα signal. Data are centred on the ERα peak, within a ± 2.5 kb window. Average density plots are shown for ChIP-seq signal for ERα in MCF7 xenografts treated with the respective conditions (bottom). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 2 GR and PR chromatin binding is induced by fasting treatment.

a. PCA plots for GR, PR and c-JUN ChIP-seq regions between the 4 conditions in MCF7 xenografts. b. Genomic distribution of GR, PR and c-JUN ChIP-seq regions between the 4 conditions. c. Heat map of GR and PR ChIP-seq signal for all 4 conditions, at differentially-enriched H3K27ac sites between TMX and TMX+Fasting (top). Regions were sorted on H3K27ac signal. Data are centred at H3K27ac peak, within a ± 2 kb window. Average density plots is shown for ChIP-seq signal of GR and PR in xenografts for all 4 treatment conditions (bottom). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM. d. Heat map depicting ChIP-seq signal for c-JUN in MCF7 xenografts for all 4 treatment conditions, visualizing differentially-enriched c-JUN sites, comparing TMX and TMX+Fasting regions (top). Regions were sorted according to decreasing c-JUN signal. Data are centred at c-JUN peak, within a ± 2 kb window. Average density plots is shown for c-JUN ChIP-seq signal for all 4 conditions in TMX+Fasting enriched regions (bottom). Data are presented as mean values ± SEM.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Tumour growth and systemic effects of fasting-reduced factors treatment and differential transcriptional activity between xenografts treated with tamoxifen alone or combined with fasting.

a. Fold-change to baseline levels of corticosterone and progesterone levels on mice blood after 4 cycles of all treatment conditions. Data are shown as mean ± SD and analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test. b. MCF7 xenograft tumour growth in six/eight-week-old female athymic nude mice in the different treatment arms. Control n = 14, TMX n = 12, Fasting n = 15, TMX+Fasting n = 12, TMX+Fasting+FRFs n = 7. n, number of tumours per treatment group. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and P-values are determined by mixed effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (see Supplementary File 1) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P-values of last day are represented). c. PCA plot based on gene expression data between MCF7 xenografts for all treatment conditions. d. Enrichment plots of the differentially enriched Hallmarks performed on transcriptomic data comparing TMX (top) and TMX+Fasting (bottom) xenografts. NES is calculated by weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and P-value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) hypothesis correction. e. GSEA for Hallmark gene sets performed on bulk proteomic data from xenografts treated with TMX alone or TMX+Fasting. f. Representative enrichment plots of the two top-differentially enriched Hallmarks performed on bulk proteomic data, when comparing TMX-enriched vs TMX+Fasting-enriched pathways. NES is calculated by weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and P-value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) hypothesis correction.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Transcriptomic analyses of BC patients treated with 5 days FMD diet.

a. Gene set enrichment analysis for Hallmarks pathways. Differentially-enriched pathways between pre- and post-5 days FMD in BC patients are shown. NES is calculated by weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and P-value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) hypothesis correction. b. GSVA enrichment scores of the GR- and PR-activity signature in transcriptomic matched samples from BC patients pre-and post-5 days of FMD. Each boxplot indicates the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution of GSVA ESs, while the horizontal line inside the box indicates the median value of the distribution. Dots indicate measurements in individual patients. P-values refer to the two-sided paired Wilcoxon test. c. Enrichment plot for PR-activity signature in matched tumour samples of BC patients Pre- and Post- 5 days FMD. NES and P-values are depicted. NES is calculated by weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and P-value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) hypothesis correction.

Extended Data Fig. 5 GR-KO MCF7 xenografts generation and response to dexamethasone treatment, in vivo.

a. Western blot for GR in NT (non-targeting) and GR-KO MCF7 cells; Actin was used as loading control. Three biological replicates were performed (n = 3). For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 1. b. Immunofluorescence for DAPI and GR in NT and GR-KO MCF7 cells. Two biological replicates were performed (n = 2). c. Xenograft MCF7 GR-KO tumour volume in six/eight-week-old female athymic nude mice treated with vehicle or Dexa. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Control n = 6, Dexa n = 5. n, number of tumours per treatment group. d. Representative IHC images for GR in MCF7 GR-KO and NT xenografts treated with vehicle or Dexa. GR-KO control n = 5, GR-KO dexa n = 4, NT n = 3. n, number of tumours analysed. e. Volcano plot of the differentially expressed transcripts between vehicle and Dexa treated MCF7 GR-KO xenografts. Differential gene expression was determined by two-sided Wald test. f. Enrichment plot of a pan-cancer GR-activity signature for the depicted conditions. NES is calculated by weighted Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and P-value determined by permutation-based testing with multiple Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) hypothesis correction.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Tumour outgrowth and body weight analyses for respective xenografts under all treatment conditions.

a. MCF7 NT xenografts tumour growth in six-eight-week old female athymic nude mice treated with the respective depicted conditions (Control n = 8, TMX n = 9, Fasting n = 8, TMX+Fasting n = 11). n, number of tumours analysed. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and P-values are determined by mixed effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (see Supplementary File 1) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P-values of last day are represented). b. Body weight changes (%) in mice during the 4 treatment cycle from the experiment performed in a. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Control n = 4, TMX n = 5, Fasting n = 5, TMX+Fasting n = 6. n, number of mice analysed. c. MCF7 GR-KO xenografts tumour growth in six-eight-week old female athymic nude mice treated with the respective depicted conditions (Control n = 7, TMX n = 7, Fasting n = 6, TMX+Fasting n = 9). n, number of tumours analysed. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and P-values are determined by mixed effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (see Supplementary File 1) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P-values of last day are represented). d. Body weight changes (%) in mice during the 4 cycle treatments from the experiment performed in c. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Control n = 4, TMX n = 4, Fasting n = 4, TMX+Fasting n = 6. n, number of mice analysed. e. Body weight changes (%) in mice during 4 weeks of depicted treatments from Fig. 4f. Data are shown as mean ± SD. Control n = 4, TMX n = 5, Fasting n = 5, TMX+Fasting n = 6, Dexa n = 4, TMX+Dexa n = 4. n, number of mice analysed. f. T47D xenograft tumour outgrowth in six-eight-week old female NSG mice in the different treatment arms (Control n = 16; TMX n = 16; Dexa n = 19 and TMX+Dexa n = 13). n, number of tumours analysed. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and P-values are determined by mixed effect model with Tukey’s multiple test correction (see Supplementary File 1) and two-tailed Student’s t-test (P-values of last day are represented). g. Body weight changes (%) in mice during 7 weeks of depicted treatments from f. Data are shown as mean ± SD. (Control n = 8; TMX n = 8; Dexa n = 9 and TMX+Dexa n = 7). n, number of mice analysed. h. Representative immunohistochemistry stainings for H&E, ERα (n = 3), GR (n = 1) and PR (n = 3) in the IDC186 PDX model. n, number of independent tumour samples. i. Body weight changes (%) in mice during 4 weeks of depicted treatments from Fig. 4e. Data are shown as mean ± SD.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Effects of Dexa treatment in circulating FRFs, TMX-induced uteri hyperplasia and PD-L1 expression levels in several immune-populations.