Main

In 1752, King Frederik V of Denmark, known for his “generous attitude […] towards natural science and applied art” commissioned the Flora Danica project, initiating an ‘Opus Incomparibile’ that took 122 years and produced one of the world’s most unique works in natural history6. Over 3,000 botanic engravings and 54 booklets were completed of flowers and plants, with which, “according to the unanimous contention of all connoisseurs”, “the whole world can eventually reap all the fruits that follow the extension of a science which, with regard to the benefit of mankind, is one of the most useful and without which medicine and economics would lack important advantages”6. In 2019, we initiated the Microflora Danica (MFD) project with the aim of cataloguing the microbiome of Denmark, in the hope that the microflora of Denmark can be similarly studied, and their riches contribute to the extension of science.

The MFD dataset

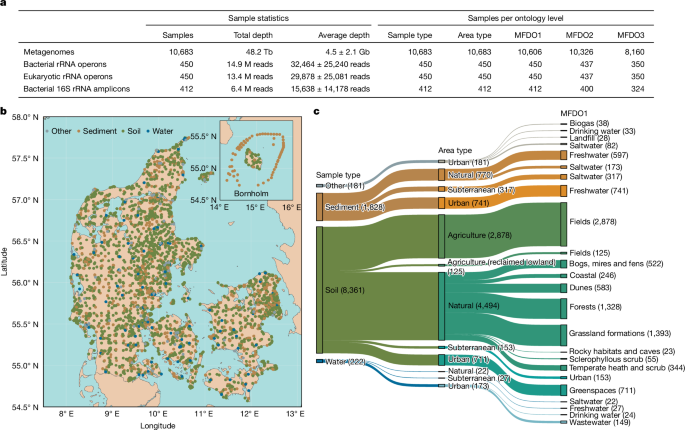

The MFD dataset comprises 10,683 samples, chosen to capture the diversity and geographical coverage of Danish microorganisms, associated with Illumina shotgun metagenomic DNA sequencing (average 4.5 Gb per sample, total 48.2 Tb) (Fig. 1a). Moreover, the dataset incorporates 14.9 million bacterial (median 4,528 bp) and 13.4 million eukaryotic rRNA operon sequences (median, 4,035 bp), as well as 6.4 million nearly full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences (median 1,355 bp). These data originate from a subset of samples (450 and 412, respectively) reflecting sample diversity while maintaining geographical coverage of the wider dataset (Fig. 1a). The samples are associated with GPS coordinates (Fig. 1b) and a highly curated five-level ontology (MFDO) (that is, habitat classification system) (Fig. 1c) that can be linked to other ontologies (EMPO3,7, Natura 2000 (ref. 8) and EUNIS9). The habitat ontology comprises sample type, area type and up to three levels of increasingly specific habitat description: MFDO1, MFDO2 and MFDO3 (MFD ontology levels 1, 2 and 3) (Fig. 1a,c). The area type ‘natural’ describes habitats not directly managed or located in urban areas. The Danish landscape is made up mainly of agriculture (63.0%), buildings and infrastructure (13.9%), forest (13.3%) and natural areas (9.2%), as well as streams and lakes (2.8%)10. The MFDO1 habitat ontology level represents 28 different categories (Fig. 1c) and reflects the primary land uses of fields (that is, croplands; 3,003 samples), grassland formations (1,393 samples), forests (1,328 samples) and greenspaces (that is, urban parks; 711 samples). The breadth of sampling is exemplified by our coverage of 27% of the 986 registered lakes in Denmark. Combined, the datasets, ontology, associated metadata and spatial resolution provide an extraordinary resource to investigate research questions related to diversity and function in microbial ecology.

a, The mean ± s.d. metagenome and rRNA amplicon data sequencing depths. The unit of measurement for depth is reads, except for metagenomes, for which the depth is reported as bp. M, million. b, The MFD samples cover the land of Denmark and its surrounding waters. The map depicts the locations of the samples used for metagenomics, and the colours represent the three different sample types. The top right cutouts show the island of Bornholm, which is east of Copenhagen and south of Sweden. The base map was retrieved from the Eurostat countries portal EuroGeographics for the administrative boundaries, © EuroGeographics 2025. c, Sample counts in the first three levels of the habitat ontology. The MFD habitat ontology accounts for a variable number of samples per category/branch. The Sankey diagram reports the first three levels of the ontology, and the thickness of the branches is proportional to the number of samples in each category. Only classes with n > 20 samples and non-empty MFDO1 classification are reported. Each habitat category is followed by the number of samples for that category in parentheses. The Sankey plot, including all five levels of the ontology, is provided in high resolution at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17162544).

Establishing Denmark’s microbiome

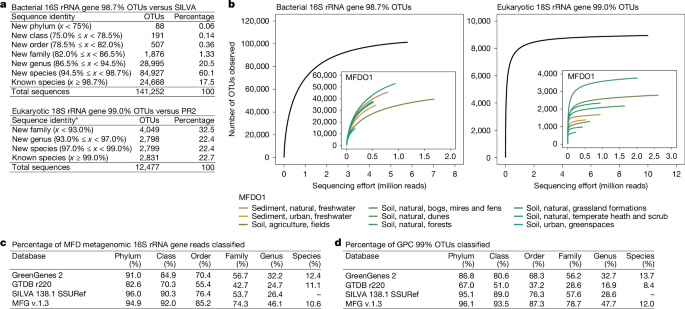

To facilitate sequence diversity analysis of bacteria, we used nearly full-length 16S rRNA genes extracted from the rRNA operon data, sequenced on the PacBio platform, and nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene amplicon data generated using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). The UMI approach relies on the use of molecular nucleotide template tagging to achieve high-accuracy single-molecule consensus calling on the Oxford Nanopore sequencing platform. The addition of UMIs to both ends of the template enables the bioinformatic identification and removal of chimeras formed during PCR11. We investigated the bacterial sequence diversity and novelty using the combination of these data (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1). The combined nearly full-length 16S (V1–V8) rRNA gene dataset included 458 habitat-representative samples and 21.3 million sequences, with 605,861 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) representing 141,252 bacterial species (98.7% operational taxonomic units (OTUs))12 (Fig. 2a). Comparison of the species-level OTUs (clustered at 98.7% identity) against the SILVA v.138.1 database revealed that 82.5% were from new species (<98.7% identity) (Fig. 2a). However, the discovery rate of novelty quickly decreased at the higher taxonomic levels, with only 1.9% of the OTUs belonging to new families (<86.5% identity) (Fig. 2a). This suggests that while 16S rRNA gene sequences from bacteria originating from temperate northern European habitats are well represented in public databases at the higher taxonomic levels, the species-level diversity remains predominantly uncaptured.

a, Sequence novelty of species-level clustered bacterial 16S rRNA gene OTUs (98.7%) against SILVA19 v.138.1 NR99 and eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene OTUs (99.0%) against PR2 (ref. 16) v.5.0.0. Taxonomic thresholds for bacteria were adapted from ref. 12, whereas those for eukaryotes were calculated using a similar approach based on sequences from the PR2 v.5.0.0 database (Supplementary Note 1). Where indicated by an asterisk, thresholds were proposed on the basis of the sequence identity between species-level classified 18S rRNA gene sequences in the PR2 database and their closest relatives within and across ranks; meaningful thresholds above the family level could not be determined. b, Species-level rarefaction curves of UMI-based bacterial 16S rRNA and eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene OTUs from terrestrial samples. Insets: MFDO1 habitat-specific rarefaction curves for habitats represented by at least nine samples. c,d, Database evaluation based on 16S rRNA gene reads extracted from selected MFD metagenomes (c) and V4 OTUs clustered at 99% identity from the GPC23 dataset (d). Classification of metagenomic reads or OTUs was done using the SINTAX63 classifier. The following databases were used in addition to the MFG database created here: GreenGenes2_2022_10 taxonomy backbone22, GTDB_ssu_all_r220 (ref. 34 and SILVA_138.1_SSURef_NR99 (ref. 19). All databases were clustered at 98.7% sequence identity to enable direct comparison.

We used the nearly full-length 16S rRNA UMI dataset to estimate the Danish terrestrial bacterial richness (species count). The dataset encompasses 5.8 million 16S rRNA gene reads and 101,423 species (98.7% OTUs)12 across 309 habitat-representative samples (Fig. 2b). Rarefaction analysis showed underlying variation in the detection of species among MFDO1-level habitats, but approached saturation across the combined dataset, indicating that most species were captured by the sequencing effort (Fig. 2b). To support this, we calculated the habitat and pan-habitat community coverage to estimate how well our dataset captures the total terrestrial diversity of bacterial species13. We found that the community coverage at the MFDO1-level habitat ranged from 0.46 to 0.90, showing a strong correlation with sampling effort r7 = 0.95 (t = 7.96, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.77–0.99, P = 9.4 × 10−5), but that the overall terrestrial community coverage amounted to 0.98, again indicating near complete species detection. Hill diversity estimates place the lower bound of the bacterial species count (Hill richness) in terrestrial MFD at a minimum of 114,400 species (95% CI = 113,897–114,902), with 43,447 common (intermediate to high frequency, Hill–Shannon14) and 22,036 dominant (most frequent, Hill–Simpson14) species based on their observation frequency in the dataset13,15. The community coverage estimates and rarefaction analysis indicate that the nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene dataset captures the collective Danish bacterial species pool across the investigated habitats and sets a conservative minimum estimate of the total environmental bacterial richness of terrestrial Denmark to be 114,400 species.

To investigate the diversity of eukaryotes, we used the eukaryotic rRNA operon sequences. These sequences exhibited a strong phylogenetic signal as they include both the ITS1 and ITS2 regions. However, the absence of a comprehensive rRNA operon reference database prompted us to focus our analysis on extracted nearly full-length (V4–V9) 18S rRNA genes that can be directly compared to the PR2 database16. The 13.4 million eukaryotic nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene sequences resolved into 28,575 ASVs representing 12,447 species (99% OTUs; Supplementary Note 1). Mapping of the species-representative sequences against PR2 revealed that most species (77%) are novel (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, 32% of the sequences had less than 93% similarity to a sequence in PR2, indicating high novelty at approximately the family level (Supplementary Note 1). Eukaryotic diversity varied between habitats but, based on Hill diversity estimates, the eukaryotic species count (Hill richness) is estimated to be a minimum of 19,295 species (Supplementary Note 2 and Extended Data Fig. 2). These findings show that vast microeukaryotic diversity remains undocumented.

MFG 16S rRNA gene database

Confident taxonomic assignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences relies on representative databases with clear taxonomic frameworks that include uncultured taxa17,18. As current universal reference databases lack the specificity we required, we used our extensive nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene dataset to create a comprehensive reference database for taxonomic classification of 16S rRNA gene reads extracted from our metagenomes. To enhance classification accuracy, we supplemented our sequences with high-quality sequences from SILVA v.138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19), EMP500 (ref. 3), AGP70 (ref. 11), MiDAS20 and ref. 21 (Methods). This resulted in a total of 30.2 million sequences, which were processed using Autotax18 to create the Microflora Global (MFG) 16S rRNA gene reference database. The 1,034,840 unique ASVs were clustered at 98.7% nucleotide identity, representing 342,673 bacterial or archaeal species-level OTUs with a complete seven-level taxonomic string.

To evaluate the MFG 16S reference database, we first compared classification of metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragments from a subset (n = 2,348; Methods) of our samples using both the MFG 16S reference database and publicly available databases clustered at the species level (98.7% identity) (Fig. 2c). We classified 46.1% (4.79 million out of 10.40 million) of all extracted 16S rRNA gene reads to genus level using the MFG 16S reference database, compared with 32.2% (3.35 million out of 10.40 million) classified by the second-best-performing database GreenGenes2 (ref. 22) (Fig. 2c). We next evaluated our database’s ability to classify data beyond Denmark’s temperate Northern Hemisphere habitats, using the Global Prokaryotic Census (GPC) V4 OTU dataset23 (Fig. 2d). The MFG 16S reference database was able to classify 47.7% (1.05 million out of 2.20 million) of the GPC OTUs at the genus level, compared with 32.7% (0.72 million out of 2.20 million) classified by GreenGenes2 (ref. 22). The combined results confirm that the MFG 16S reference database greatly improves classification not only for our samples, but for microbial profiling in general.

Diversity for habitat management

The level of microbial diversity in a habitat is often characterized by the alpha diversity, the richness in a single sample or average sample of a habitat and by the gamma diversity, the total observed richness of all samples within a habitat24. In contrast to the aboveground macro biodiversity, disturbed (that is, managed or directly affected by human activities) soils have been shown to have higher richness than undisturbed natural areas, both at continental and global scales24,25. Our detailed habitat ontology and the number of samples in each habitat type enabled us to re-evaluate these observations using both the metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragments and the nearly full-length 16S UMI rRNA gene dataset taxonomically classified against the MFG 16S reference database.

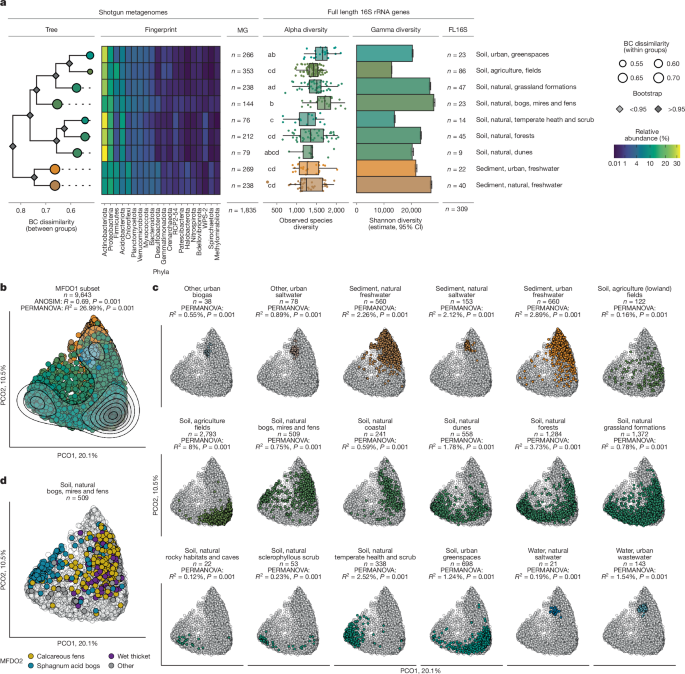

To ensure that our data enabled valid comparisons between samples, we investigated biases introduced from sample treatment and location. Most of the agricultural samples were treated differently compared with the other soil samples (Methods), but this treatment had no observable effect on alpha and beta diversity and amounted to only around 2% of the community variation (Supplementary Note 3). We accounted for spatial bias resulting from more densely sampled locations by estimating the spatial autocorrelation using distance–decay analysis on the metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragments (Extended Data Fig. 3). On the basis of the results, we identified representative samples of the MFDO1 habitats within the 10 km reference grid of Denmark (2,348 samples; Methods and Extended Data Fig. 1). Hierarchical clustering based on the average between-habitat Bray–Curtis dissimilarity of these samples (beta diversity) largely captured the expected relationships based on similar aboveground characteristics (for example, grass cover, monocultures, exposure) between the habitats. These relationships are exemplified by the clustering of fields, greenspaces and grassland formations (Fig. 3a).

a, Diversity overview of the selected habitats. Each facet addresses a different measure of diversity. The nine MFDO1 habitats are represented in the rows of the multifacet plot. The dendrogram shows the between-group (branches) and within-group (nodes) Hellinger-transformed Bray–Curtis (BC) dissimilarity using the genus-level-classified 16S rRNA gene fragments from the spatially thinned dataset. Bootstrap values were calculated using 100 iterations. The heat map shows the relative abundances of the 20 most abundant phyla. The box plots of alpha diversity and bar charts of gamma diversity are based on the UMI 16S rRNA gene data. The number of biologically independent samples used for the diversity measurements per habitat are indicated. The hinges of the box plots correspond to 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of the distributions, and the whiskers extend to 1.5× the distance between the 25th and 75th percentile. All individual samples are shown as points (with jitter for visualization). Gamma diversity (Hill–Shannon diversity) reflects a single value per habitat (that is, bar) based on rarefaction and extrapolation of n samples, and the error bars report the associated 95% CIs. b, Ordination of the metagenome (MG) dataset. PCoA of the 9,643 metagenome samples and coloured according to MFDO1 habitat description together with the results from the ANOSIM and PERMANOVA; P values were derived from 999 permutations in both cases. The visualization depicts the first two components. The contour plot was added to show the density of points. c, Subpanels of the individual 18 selected MFDO1 habitats coloured and presented with the results of the contrasts analysis. d, The sample distribution in the ordination space for MFDO1 ‘soil, natural, bogs, mires and fens’, coloured by classifications at the MFDO2 ontology level.

We calculated the alpha diversity from the nearly full-length UMI 16S rRNA gene data. In contrast to previous studies at the continental-Europe25 and global24 scale, which found the highest alpha diversity in samples from disturbed habitats, we found that the median bacterial diversity was highest in bogs, mires and fens (1,705 species) and lowest in temperate heath and scrub (1,274), with the diversity of disturbed habitats ranging in between (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Note 4). We found no significant difference in alpha diversity between fields, forests or grassland formations, contradicting the previous results from continental Europe while agreeing with global findings (Fig. 3a, Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Note 4). Additional large studies on other continents will be vital to resolving the effect of human disturbance on alpha diversity.

In contrast to the alpha diversity results, gamma diversity revealed key differences between disturbed and natural habitats (Supplementary Note 4). Fields had the lowest gamma diversity (12,797 common species), and along with greenspaces (20,336), was considerably less diverse than the more natural environment grassland formations (26,721). This trend was mirrored by sediments, with urban sediments (21,609) encompassing lower gamma diversity than natural sediments (27,126). Human disturbance reduces ecological breadth by creating more uniform environmental conditions, leading to lower gamma diversity26. This was supported by our comparison between urban and natural environments, in which greater environmental heterogeneity is encompassed by the natural habitats, reflecting greater habitat breadth and, consequently, higher gamma diversity. Overall, these data suggest that there is a gamma diversity gradient impacted by the level of perturbation, from highly disturbed fields to moderately disturbed greenspaces and relatively undisturbed grassland formations. These findings support an apparent homogenization (that is, low gamma diversity considering the high alpha diversity) of species in disturbed habitats—a pattern that was recently identified in other studies27. Habitat species homogenization was also supported by the Bray–Curtis analysis, which revealed low within-habitat dissimilarity of the prokaryotic communities (Fig. 3a).

Low gamma diversity in fields was most pronounced among bacterial communities (Fig. 3a), but also visible in the eukaryotic data (Supplementary Note 2), and reflected the aboveground macro biodiversity. Notably, temperate heath and scrub had similarly low gamma diversity to fields, but also low alpha diversity. However, this habitat is selective, defined by dry, infertile and acidic conditions (EUNIS habitat classification9), in contrast to the irrigated, nutrient- and pH-adjusted agricultural land.

These results show that the same bacterial species are found in the disturbed habitats, and that disturbed habitats are under selective pressures comparable to natural habitats with defined abiotic constraints. This highlights the need to incorporate gamma diversity when assessing microbial diversity. Including this broader perspective is particularly important when monitoring the impacts of land use and climate change, where community homogenization could lead to reduced ecosystem resilience and have implications for ecosystem functions28.

Modelling for habitat classification

After revealing the importance of gamma diversity for biodiversity assessments, we investigated how the microbial community could be used to classify habitats and its potential for tracking future habitat changes. Exploratory principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) performed on the eukaryotic 18S rRNA gene dataset revealed some separation between MFDO1 habitat categories (n = 363, analysis of similarities (ANOSIM), R = 0.46, P = 0.001, permutational analysis of variance (PERMANOVA), R2 = 0.07, P = 0.001; Supplementary Note 2). However, for the prokaryotic community, PCoA revealed good separation between MFDO1 habitats based on the metagenome-derived 16S rRNA gene fragment microbial community composition (n = 9,643, ANOSIM, R = 0.69, P = 0.001, PERMANOVA, R2 = 0.27, P = 0.001) (Fig. 3b,c). An exception was MFDO1 ‘bogs, mires and fens’, which showed large dispersion in ordination space. At the MFDO2 level, this habitat consists of both calcareous fens and sphagnum acid bogs, which have large differences in pH that impact microbial communities29 (Fig. 3d).

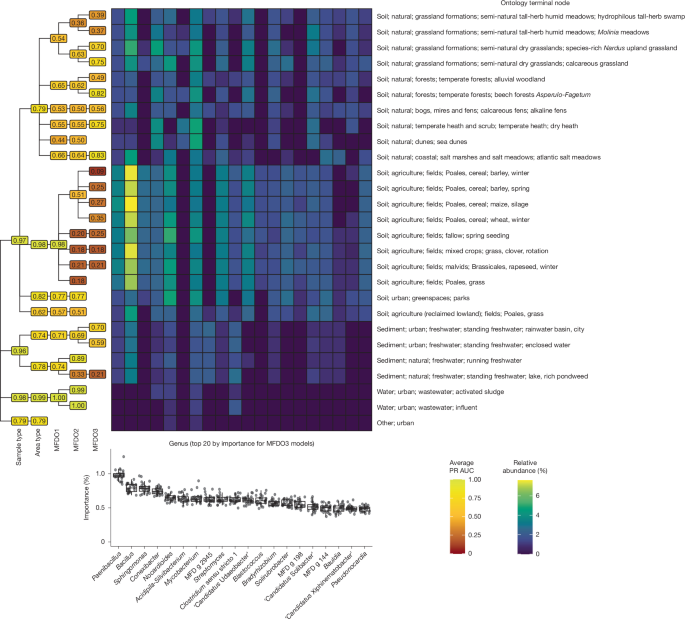

To determine the potential for microbial community DNA to be used in habitat classification, we investigated whether the 16S rRNA gene fragments could predict the habitat ontology (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 5). We evaluated habitat classifications using the precision recall area under the curve (PR-AUC; Fig. 4). Some habitats were difficult to model, for example, they had a lower PR-AUC (Fig. 4), such as the various types of fields, where the level of shared taxa was large. Conversely, other habitats—such as saltwater and wastewater, with higher PR-AUC—are associated with more specialized microbiomes. In general, low model scores reflected habitats in which samples would be misclassified to a few other selected habitats, for example, samples from grassland formations, greenspaces and fields were often misclassified as each other (Supplementary Note 5).

The genus-level models were used to compile the per-class PR-AUC of every node of the ontology. The metric spans from 0 to 1, where 0 and 1 mean that none and all, respectively, of the samples of the given class were classified correctly. The mean results over iterations (n = 25 independent iterations) are reported in the tree labels and coloured accordingly, with brighter nodes carrying higher values. Moreover, the top 20 genera, according to variable importance (box plot at the bottom, computed using the MFDO3 models), are reported with their median relative abundance for each of the terminal nodes of the ontology. The three hinges of the box plots correspond to the 25th, 50th and 75th percentiles of the distributions, and the whiskers extend to a maximum of 1.5× the distance between the 25th and 75th percentile hinges. All of the individual samples are shown as points (with jitter to improve visualization). The sum of the variable importance across all variables was scaled to 100 for each model. The ranking of the variables indicates which genera have a greater discriminant power in the models. Notably, the models were reliable in classifying samples from agricultural soils (PR-AUC =0.95) but not at classifying individual crop types.

Considering which prokaryotic genera were the most important in discriminating among habitats (that is, highest variable importance) (Fig. 4), the strongest signal was provided by Paenibacillus, whose species have been found to be associated with crops, promoting plant growth and protection from pathogens, as well as fixation of nitrogen30. Paenibacillus was distributed across soils and sediments with higher counts in field habitats, perhaps functioning as a predictor for sample type and land use. Our findings support low-resolution discrete habitat classification (that is, MFDO1) using microorganisms, but not higher-resolution classifications (that is, MFDO2). This agrees with previous studies proposing the redefinition of habitats using continuous gradients31. We believe microbiome data could provide a scalable solution to future classification efforts, enabling gradients to be compared to measure or monitor changes related to climate, sustainable farming choices or restoration progress. Identifying the core microorganisms belonging to specific habitats, or habitat gradients, may help to simplify the use of microbiome data.

Core genera across Danish habitats

Core microorganisms are abundant and widespread within habitats, potentially reflecting populations with habitat-specific adaptations, functions and ecological importance32. We identified abundant core community genera in the habitats across all five habitat ontology levels (genera with more than 50% habitat-specific prevalence, as well as at least 0.1% relative abundance; Supplementary Data 1, Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 6).

Habitat-specific core genera were more numerous in habitats with strong selective environmental gradients (for example, halotolerance), or constrained habitats, such as biogas systems (Supplementary Data 2 and Extended Data Fig. 4). Conversely, we observed fewer habitat-specific core species if no habitat-specific selective pressure was present. For example, the median of core genera unique to the soil MFDO1 habitats was two, showing that many of the genera were shared among two or more MFDO1 habitats (such as fields and greenspaces). Combined with the observed model misclassification of ecologically similar environments, these findings suggest that despite the vast dispersal capabilities of microorganisms, the prokaryotic community follows a continuous gradient of change and is thus more influenced by specific environmental factors as opposed to geographical location, in accordance with the Baas Becking hypothesis: everything is everywhere, but the environment selects33.

The alpha, beta and gamma diversity patterns, and high model score for fields among the terrestrial environments (Fig. 4), showed that land disturbance and management lead to similar microbial communities (Fig. 3a). Land-management practices, such as nutrient amendment and soil structure degradation, probably drive environmental filtering of the prokaryotic communities27. The disturbed soil habitats (fields, roadside and greenspaces) and the natural soil habitats (bogs, mires and fens; coastal; dunes; forests; grassland formations; rocky habitats and caves; sclerophyllous scrub; and temperate heath and scrub), encompassed 107 and 98 core genera (that is, a core genus in at least one of the habitats under the disturbed or natural categories), respectively (Supplementary Note 6). Comparing the natural and disturbed habitats revealed differences in core genera associated with nitrogen cycling (for example, Nitrospira, and genera within the Nitrososphaeraceae and Nitrosomonadaceae; Extended Data Fig. 4 and Supplementary Note 6), leading us to investigate this functional group more closely.

To provide genome-level resolution, recover potential functional group members and improve the representativeness of public genome databases, such as the Genome Taxonomy Database34 (GTDB), we performed de novo assembly of the 10,683 metagenomes (Supplementary Note 7). We recovered 19,253 bacterial and archaeal metagenome assembled genomes (MAGs) of at least medium quality (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 5). These MAGs represented 5,518 species (95% average nucleotide identity clustering) with broad phylogenetic coverage of which 4,604 were novel compared with GTDB34 R220 (Supplementary Note 7). This MFD genome database provides the foundation for functional analysis linked to species identity and habitat distribution and enabled us to examine key participants in the biogeochemical nitrogen cycle, the nitrifiers, across Denmark.

Distribution of Danish nitrifiers

Our investigations into microbial diversity indicated that bacteria and archaea involved in the nitrogen cycle were abundant, and form part of the core community differences in disturbed versus natural habitats (Supplementary Notes 6 and 8). This microbiome fingerprint reflects that Denmark is one of the most intensively cultivated countries in the world (63% of the land10), with much of its land impacted by management regimes involving fertilization with reactive nitrogen35. As Denmark has a large livestock sector, manure is a major nitrogen source, alongside synthetic fertilizers. Conversion of nitrogen fertilizers by nitrifying microorganisms leads to fertilizer loss, groundwater nitrate contamination, eutrophication of aquatic water bodies, and production of the potent ozone-depleting and greenhouse gas nitrous oxide35,36. Consequently, nitrification inhibition with synthetic or biological inhibitors is gaining importance to limit nitrate leaching, nitrous oxide emissions, and to increase nitrogen-use efficiency36. The use of two commercial nitrification inhibitors has risen fivefold in the past five years, now covering around 3% (78,129 ha in 2025) of Danish agricultural land37. Notably, the different groups of nitrifiers, comprising ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) and archaea (AOA), complete ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (CMX) and nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB), vary in their sensitivities to nitrification inhibitors and in their nitrous oxide production rates36,38. To build knowledge needed to move towards sustainable agriculture, we performed an in-depth analysis of nitrifiers in the MFD datasets. On the basis of an analysis of functional genes (GraftM39), single-copy marker genes (SingleM40) and genome-level quantification (sylph41), we describe the diversity and distribution of Danish nitrifiers and identify new uncharacterized AOAs and NOBs.

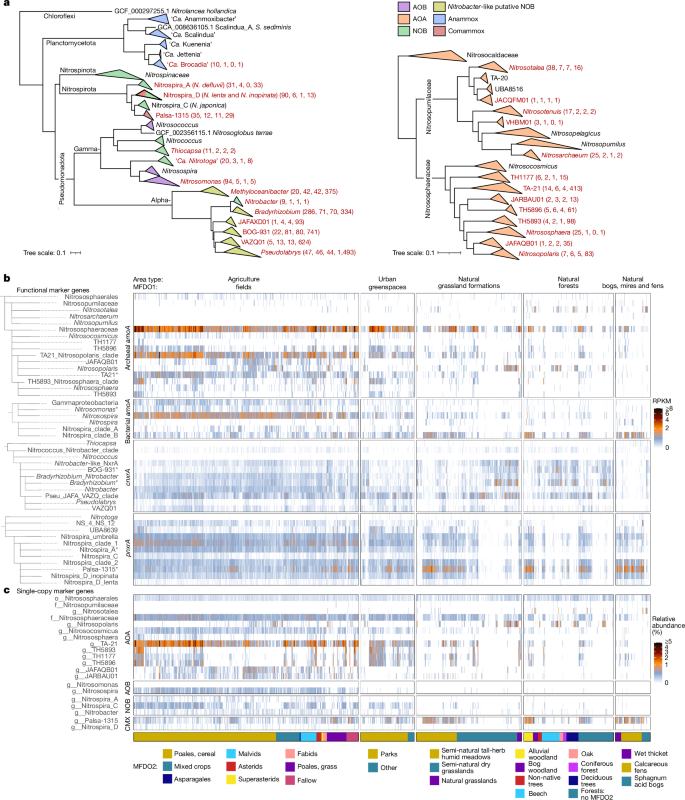

Initially, curated gene-based search models of the nitrification marker genes amoA (encoding a subunit of the ammonia monooxygenase of AOB, AOA and CMX) and nxrA (encoding the active-site subunit of nitrite oxidoreductase of NOB and CMX) were created, accompanied by detailed classification of protein phylogeny from the translated genes, to separate nitrifier sequences from homologous sequences in other microorganisms, such as PmoA (particulate methane monooxygenase) and NarG (nitrate reductase)42. Furthermore, we included translated amoA and nxrA sequences from the recovered MFD MAGs in the search models, which markedly improved the resolution within groups of nitrifiers with few representative sequences (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Note 9).

a, Phylogenomic tree of nitrifiers. The red text indicates groups for which we recovered MAGs; the numbers in the brackets indicate the total number of species in this group in GTDB R220 (ref. 34), the number of species recovered in MFD, the number of species recovered in MFD not present in GTDB R220 and the total number of MAGs recovered in MFD. The values in parentheses represent the GTDB number of spp. representatives, the MFD number of spp. representatives, the MFD number of spp. representatives not in GTDB, and the MFD total number of MAGs, respectively. b, The distribution of nitrification genes across Danish habitats. The number of reads (reads per kilobase million (RPKM)) assigned to each gene-phylogenetic group (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 9). In cases in which a taxon has polyphyletic amoA or nxrA clades (Supplementary Note 9), an asterisk indicates the aggregation of multiple clades into a single line in the heat map. The samples are clustered with hierarchical clusters within each MFDO2 habitat. The bottom colour panel indicates the MFDO2 habitat. c, The distribution of canonical and potential nitrifiers across Danish habitats based on single-copy marker genes (SingleM). The heat map of short-read metagenomes is based on SingleM with the metapackage supplemented with MAGs from the MFD short-read metagenomes. Taxonomic resolution is marked by prefixes based on GTDB taxonomy: o__ (order), f__ (family) and g__ (genus). Reads assigned to higher taxonomic ranks, such as ‘f__Nitrososphaeraceae’, exclude descendants and consist only of those unassigned to a specific lower rank. pNxrA gene fragments assigned to the ‘Nitrospira_clade_1’ clade in the pNxrA tree (b) probably come from genomes of species in the GTDB genus Nitrospira_C (c), as the abundances of the pNxrA group and Nitrospira_C (based on single-copy marker genes) follow the same trends.

Analysis of the disturbed soil habitats showed similarities in their nitrifier communities, suggesting homogenization due to similar interferences, such as increased N availability, reduced aboveground diversity or physical soil disturbance. The highest relative gene abundances of canonical ammonia oxidizers (AOA and AOB) were observed in fields and greenspaces (Fig. 5b,c). These habitats were dominated by Nitrosospira AOB and Nitrososphaeraceae AOA. AOA distributions have been linked to soil acidity, as well as fertilization management regimes43. Furthermore, liming and inorganic fertilizer application in agricultural soils may create conditions in which Nitrosospira can also thrive43, as seen by the preference of Nitrosospira in fields. Similar to other studies44,45, AOA were more abundant than AOB in agricultural soils, in particular genera within the Nitrososphaeraceae, such as Nitrosocosmicus and several uncharacterized genera lacking isolates (TA-21, TH5893, TH5896, TH1177). Importantly, we were able to link these uncharacterized AOA genera to the major terrestrial amoA clades of uncharacterized groups through phylogenetic analysis of the amoA genes in their genomes (TA-21/NS-δ, TH5893/NS-γ 2.1, TH5896/NS-β 1 and TH1177/NS-ε)44,46 (Supplementary Data 3). By mapping nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene reference sequences to the MAGs, we linked two of these genera, TA-21 and TH5896, to core genera within the disturbed soil habitats (TA-21/MFD_g_198, TH5896/MFD_g_4907) (Supplementary Note 6).

Although AOA are generally abundant in agricultural soils, we identified a single undescribed AOA species, TA-21 sp02254895, that was highly abundant (sylph taxonomic abundance, median = 4.6%, maximum = 25.2%) across nearly all field samples and represented by 320 MFD MAGs (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 8). Furthermore, the same species displayed lower relative abundance in agricultural field subhabitats (MFDO3) permanent grass, low yield (Mann–Whitney U-test, U = 10,628, one-sided, P = 1.23 × 10−5) and fallow fields, spring seeding (Mann–Whitney U-test, U = 41,104, one-sided, P = 0.045) (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Note 8) and was sparsely present in other non-agricultural soils except for urban parks (Mann–Whitney U-test, U = 90,748, one-sided, P = 3.01 × 10−20) and semi-natural grasslands (MFDO2), such as agricultural meadows (MFDO3) (Mann–Whitney U-test, U = 9,219, one-sided, P = 2.3 × 10−5) (Fig. 5, Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Note 8). The abundance of TA-21 sp02254895 across Denmark varied with land-use intensity and might be an effect of the level of anthropogenic disturbance. Owing to its link to disturbed Danish habitats, we propose the name ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’.

Functional genome annotation of ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ revealed the potential to use ammonia (amoABC) and urea (ureABC) accompanied by ammonia (amt1/amt2) and urea transporters, CO2 fixation through the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle47 (acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase (accC/pccC), methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (mcmA1, mcmA2), 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (abfD)) and several genes involved in degradation of peptides (MEROPS IDs: cysteine C44, C26; serine S09C; threonine T01A; and metallopeptidases M38, M41, M48B) and polysaccharides (CAZyme IDs: GT2, GT55, GT81, CE1, CE14, CBM32, GH5). Specifically, GH5 and CBM32 were found in multiple copies (Supplementary Data 4), and have previously been reported to be highly expressed in the TA-21/NS-δ clade48. The mixotrophic potential of ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ might explain discrepancies between TA-21/NS-δ amoA abundance and nitrification and carbon-assimilation rates49, and future studies are needed to clarify whether this widespread and very abundant organism is growing through autotrophic ammonia oxidation. As N2O production is much lower from AOA than from AOB43,44,45, understanding the distribution and energy metabolism of archaeal species such as ‘Candidatus Nitrososappho danica’ will prove vital in managing the environmental impact of agricultural soils.

Moreover, recent studies suggest that CMX Nitrospira may be more abundant and important to soil nitrification processes than previously thought50. This is of particular interest, as CMX Nitrospira, like AOA, produce less N2O than canonical AOB do51. We identified Nitrospira as part of the core genera of disturbed soil habitats (Supplementary Note 6), but canonical and CMX Nitrospira are difficult to differentiate based on nxrA and 16S rRNA genes52. By using amoA gene phylogeny, we were able to assign CMX Nitrospira to its clade A and B subtypes52, which were found within the genera Nitrospira_D and Palsa-1315 (GTDB34 R220), respectively. Palsa-1315, first named from MAGs found in a permafrost peatland53, is probably a new comammox genus54. This is supported by a linear correlation (R2 = 0.48–0.81) between Nitrospira clade B amoA and Palsa-1315 nxrA in various MFDO1 habitats (Extended Data Fig. 7), and by identified amoA and nxrA in the recovered MAGs (Fig. 5a).

Notably, our improved search models showed that CMX clade B, for which no cultured representative is available, was more abundant than CMX clade A in most habitats, especially natural soils (Fig. 5b,c) and sediments (Supplementary Note 9). This challenges previous perceptions that CMX clade B is not abundant in forest soils55, wetland sediments56, and acidic or fertilized agricultural soils50,57. Nitrospira clade A amoA was inconsistently identified in sediments and agricultural soils, and was nearly absent from the other habitats investigated (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Note 9). Our analysis highlights CMX clade B as the most abundant ammonia oxidizer in Danish natural habitats, especially the MFDO2 habitats calcareous fens, alluvial woodland and semi-natural humid meadows, while canonical AOB and AOA were more abundant in disturbed habitats. Considering this, we propose the name ‘Candidatus Nitronatura plena’ for the species represented by a circular MAG, to describe the natural, widespread distribution of this most likely complete ammonia oxidizer. Nitrospira_C was the most abundant canonical NOB genus based on single-copy marker genes (Fig. 5c) and reads placed in the nxrA Nitrospira_clade_1 group (Fig. 5b), and displayed similar habitat patterns to the AOA, albeit at a lower abundance. At the national scale, it appears that nitrifier communities clearly reflect different habitat types, with their structure influenced by human impact. Here, we show that we can link specific species across land use types at scale.

Nitrobacter, a widely studied model organism of NOB, is considered abundant in fertilized soil based on nxrA identification58. However, our detailed search for NXR-encoding MAGs indicates that Nitrobacter may have been strongly overclassified, as we found NxrA sequences (>600 amino acids) phylogenetically falling between Nitrobacter and Nitrococcus (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Notes 9 and 10). While other studies have reported cytoplasmic nxrA sequences clustering near, but outside of, cultivated Nitrobacter representatives in agricultural soils58, we were able to link these Nitrobacter-like NxrA sequences to Xanthobacteraceae family members, primarily Bradyrhizobium spp., Pseudolabrys spp. and the uncharacterized genus BOG-931 (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Note 10), which are not known to be NOB. In particular, a monophyletic clade of Nitrobacter-like NxrA from BOG-931 grouped closely to Nitrobacter and Nitrococcus NxrA, and the associated MAGs clustered together in a phylogenomic tree (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Note 10).

We investigated gene synteny in long-read high-quality MAGs belonging to BOG-931 recovered from MFD samples59. Metabolic reconstruction revealed an operon resembling the nxr/nar operon of Nitrobacter winogradskyi and Nitrobacter hamburgensis60, consisting of cytochrome c class I, nxrA, nxrX, nxrB/narH, narJ and narI, and was flanked by transposases, accompanied by formate/nitrate transporters and cytochrome c oxidase gene clusters (Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Note 10). Consequently, Nxr-encoding members of BOG-931 could be potential new NOB occurring in many habitats, but confirmation requires culturing (Supplementary Note 10).

The putative Nitrobacter-like nxrA groups were found across fields, forests, grassland formations and greenspaces (Fig. 5b). In fields, Nitrobacter and Nitrobacter-like nxrA genes were present independent of crop type, but were less abundant than canonical Nitrospira NOB, such as Nitrospira_C (Fig. 5b,c). BOG-931 was most abundant in forest soils, and Nitrobacter and Nitrobacter-like NOB have previously been associated with nitrogen amendment in forest soils61. Indeed, BOG-931 was detected mainly in soil habitats lacking detected CMX clade B, and was particularly abundant in forests, grassland formations and sphagnum acid bogs of the bogs, mires and fens habitat (Fig. 5b). This suggests niche differentiation between CMX and canonical or potential NOB, and underlines a general need for further investigation of uncultured but abundant nitrifiers, including Nitrobacter nxrA-like containing groups, CMX clade B and AOA TA-21. As the presence and abundance of nitrifiers may be applied to evaluate how human activities affect the nitrogen cycle44, our results stress the importance of developing and applying reliable methods for quantitatively recording their diversity and distribution. Such methods must cover all important groups, including the newly detected nitrifiers, and provide insights into their response to environmental factors. The most critical of these factors is climate change, whereby the increased temperatures and longer growing seasons may lead to increased or prolonged nitrification activity, and more frequent droughts may lead to increased AOB activity but reduced AOA and CMX activity in soils62.

Conclusions

Here we provide an atlas of Denmark’s microbial communities, establishing a national baseline of microbial diversity. While many habitats have distinct microbial profiles, some show unexpected similarities undetectable through flora-inferred classification (for example, fields and greenspaces). These may result from land management disturbances, which enhance species diversity while also driving homogenization as communities affected by human disturbance converge. This homogenization extends to function, with nitrifier communities reflecting habitat type and human impact. Integrating gamma diversity metrics into biodiversity assessments may help to prevent national microbiome homogenization. Future assessments could adopt a data-driven approach, as our models show that short-read data can match microbiomes to flora-inferred habitats. The next step is linking microbial species and guilds, such as nitrifiers, to other national research efforts, including historical land use, fertilization regimes and greenhouse gas emissions. Through the identification and characterization of new species, microbially informed agricultural management is within reach, offering a potential strategy to limit N2O emissions by tailoring inputs to encourage or discourage specific microorganisms. We hope that other national atlases will follow, enabling comparisons of diversity and distribution on other continents. As we stand at the precipice of profound climatic shifts, the MFD dataset will be a vital resource for tracking microbial adaptations and resilience in both disturbed and natural ecosystems and a standard from which to monitor future restoration efforts.

Methods

Sampling

The MFD sample collection includes samples collected as part of the MFD sampling campaign, as well as samples contributed by members of the MFD consortium. The samples taken as part of the MFD sampling campaign were registered and associated with the appropriate metadata using codeREADr (https://www.codereadr.com) using a linear barcode attached to sterile 100 ml sample containers. After collection, the samples were stored between 4 °C and 10 °C for up to 48 h before being deposited at −20 °C for later processing.

As we wanted to cover as much of the Danish environmental landscape as possible, we requested expert collaborators send existing samples from interesting environments or environments that are not easily sampled. These include samples from existing publications, samples collected as part of governmental monitoring, but also samples from collaborators with no current publication. If not otherwise stated, these samples were acquired as frozen sample material. We divided each set of samples into projects, in which samples of the same type (soil, sediment, water) were subjected to the same treatment. Based on this, we constructed summary tables over the different protocols used for sampling and DNA extraction methodology (Supplementary Data 5). Most samples (across the biggest sample groups) were treated similarly, but we acknowledge that the different treatments might affect the results; consequently we applied the appropriate filtering where needed. The number of subsamples and other related sampling metadata are provided at GitHub and in Supplementary Data 6.

Soil samples

Topsoil samples from the MFD sampling campaign were collected as up to five subsamples (0–20 cm), taken within a ∼80 m2 (5 m radius) sampling area using a weed extractor, which was cleaned with 70% ethanol between sampling sites. As DNA from microorganisms could potentially be overwhelmed by the DNA from whole specimens in the sample material, we visually inspected each subsample with the naked eye and avoided including complete specimens (grass, leaves, sticks or larger animals) in the samples. After specimen removal on site, the subsamples were combined in a sterile plastic bag, the bag closed and the collective sample homogenized by hand before up to 100 ml was transferred to the barcoded sample container (P04_2, P04_4, P04_6, P04_7, P08_1, P08_2, P08_3, P08_5, P08_6, P08_7, P08_8 and P17_1). The samples from projects P19_1, P20_1, P21_1 (ref. 64) and P25_1 were collected as single subsamples. The subset of topsoil samples from the Land Use and Coverage Area Frame Survey (P04_8)25 were collected by collaborators from Aarhus University as described in previously65, in a manner very similar to the MFD sampling campaign.

A subset of the topsoil samples (P01_1)31 from both natural and agricultural habitats were provided by collaborators from Aarhus University and Copenhagen University. These were collected as described previously31. In brief, 81 subsamples, spanning a 9 × 9 grid covering a 40 × 40 m plot, were mixed into a representative sample from which we acquired a subsample. New sample projects were added to extend the existing project with wet terrestrial habitats (P01_2), agricultural and semi-agricultural habitats (P02_1), sites with different agricultural practices (P02_2 (ref. 66)) and urban habitats (P03_1 (ref. 67)). These were all collected as 81 subsamples except in the case of P03_1 which was mixed from 9 subsamples.

Samples from subterranean soils were collected as single samples from different depths using a soil drill (P06_1, P06_2, P06_3). Subsurface soil (P06_1) was collected with PVC liners by percussion hammering using a Geoprobe (NIRAS) drill rig. Soil samples were then collected around the oxic-anoxic interface with 5 ml cut-off syringes through openings cut into the core liners. We acquired the samples from P06_3 as DNA, which had previously been extracted using the DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In the case of agricultural soils from croplands, six out of every seventh sample was provided by SEGES. As part of the collection, the individual samples were frozen, crushed to particles below 1 cm in size and dried at 37 °C (P04_3, P04_5), the effect of which was investigated (Supplementary Note 3).

Sediment samples

Surface sediment samples (0–10 cm) from the MFD sampling campaign were collected as up to five sediment subsamples from across the sampling area using a gravity corer, which was cleaned with 70% ethanol between sampling sites. The subsamples were combined in a sterile plastic bag, the bag was closed and the collective sample was homogenized by hand after careful removal of larger debris and any collected water. Up to 100 ml of the homogenized sample was transferred to the barcoded sample container. For the sediment from standing water sources (P05_1, P05_2, P08_5, P09_1, P09_2, P11_1 and P11_3) the top 10 cm was collected, while only the top 5 cm was collected from streams (P10_1, P10_2 and P10_3). Pond sediment (P09_2) was collected from the deepest point of each pond. Stream samples were collected as three subsamples across a 20 m transect of the stream, two at 25% distance from each brim and one in the middle of the stream.

Lake sediments provided by University of Southern Denmark were from either lakes selected for investigation of biotic phosphorus dynamics (P09_3) or a lake restauration initiative (P09_4). For P09_3, the cores were taken from the deepest part of the lake. For P09_4, the cores were taken at five different sampling stations. In both cases, a gravity corer was used for the sampling68. Sediment samples from coastal areas (P11_2) were collected at a single point using a HAPS bottom corer, as described previously69. Each sample was mixed from 10 subsamples of the sediment core (0–2 cm and 5–7 cm). We acquired the samples as DNA, which had previously been extracted with the DNeasy PowerMax Soil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

We acquired DNA extracts from Aarhus University from multiple sampling campaigns of marine surface and subterranean sediments (P12_1 (ref. 70), P12_2 (refs. 71,72)). P12_1 holds samples from the Bornholm Basin stations BB01 (13–63 cm) and BB03 (19–73 cm) sampled with a Rumohr corer. Samples from P12_1 were previously extracted with the DNeasy PowerLyzer PowerSoil Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol while phenol-chloroform-isoamyl-alcohol extraction was used for P12_2. We expanded this sample category with sediments from the Baltic Sea provided by WSP Denmark (P12_5). Top sediments (0–30 cm) were collected using a HAPS bottom corer while subterranean sediments (0–300 cm) were collected using a Vibrocore sampler.

Water samples

Besides the samples from fjords (P11_3) the diversity in the natural environments found in the soil and sediment categories is not reflected in this category. The water category is instead made up of samples with a link to the urban environment: drinking water from the waterworks stage (P16_1 (ref. 73), P16_3 (ref. 74)), tap water (P16_1), potentially polluted groundwater (P16_4) and samples from wastewater treatment plants (P13_1 (ref. 75), P13_2 (ref. 75)).

Water samples from fjords (P11_3) were collected with a 1 l Ruttner water sampler. The sampler was rinsed three times with water from the locality before the water samples were collected. At each sampling location, five 1 l water samples were randomly collected. The water samples were transferred to 5 l cleansed plastic bottles and stored in a cooler (< 8 h) until they could be filtered in the laboratory. At stations with a halocline, water samples were collected from both above and below the halocline and were treated as two separate events. The collected water was filtered through a mixed cellulose ester membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm) by dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump. The amount of water filtered for each sampling site varied from 0.3 l to 1 l. Filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples of drinking water (2 l) from the drinking water treatment plants (P16_1) were filtered through a mixed cellulose ester membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm). The amount of water filtered varied from 0.25 l to 1.8 l. Tap water (5 l) was filtered through a cellulose acetate membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm). The amount of water filtered varied from 4 l to 5 l. In both cases, filtering was performed as dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump and the filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted from the filters using the DNeasy PowerWater Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The samples in P16_4 of probable polluted ground water (1 l) were filtered through a cellulose nitrate membrane (47 mm, 0.22 µm) by dead-end filtration using a sterile filter funnel and a vacuum pump. The amount of water filtered varied from 0.5 l to 1 l. Filters were stored at −20 °C before DNA was extracted from the filters using the DNeasy PowerLyzer Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

The Technical University of Denmark provided DNA extracted from concentrates. Samples were taken from raw water (abstracted groundwater), filtered water (after secondary sand filters), treated water (after ultraviolet treatment) and water from the distribution network (P16_3). Between 100 l and 250 l of water from the different sampling points was pumped through separate REXEED 25S filters at a constant rate. After sample elution (200 ml) from the REXEED filter, a secondary concentration was conducted using VivaSpin 15R (SATORIUS) filters and centrifugation at 3,500g. DNA was extracted from 100 µl of final concentrate using the NucliSens miniMAG platform and NucliSens Magnetic Extraction Reagents (bioMerieux) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Samples from wastewater treatment plants were included as DNA samples extracted with the FastDNA Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals). Wastewater was sampled as both influent (P13_1), using flow proportional sampling, and activated sludge from the aeration tank (P13_2) as described previously75.

Other samples

We included a last group of samples to encompass the samples that did not directly fit into either of the soil, sediment and water categories. This category covers samples from various surfaces in harbours (P18_1 and P18_2), sand filter material from drinking water treatment plants (P16_2 and P16_3), sludge from anaerobic digesters (P13_3), and scrapings from the walls of a limestone mine and a salt vat (P25_1). The harbour samples (P18_1 and P18_2) were collected as individual scraped-off biofilms and biocrusts from a range of different surfaces (such as fenders and piers). Each sampling location is associated with three individual samples. Sand filter material in P16_2 was collected as described previously76. The pooled medium samples were made by homogenizing and combining 20 g subsamples from 20 cm depth intervals. For P16_3 the sand filter material (around 15–40 ml) was collected from 1–2 locations at the top of 12 groundwater-fed rapid sand filters of 11 Danish waterworks using a 1% hypochlorite-wiped stainless-steel grab sampler. Samples from anaerobic digesters (P13_3) were collected from 20 digesters across Denmark, with DNA extracted using the standard DNeasy PowerSoil Pro Kit (QIAGEN) according to published protocols20.

Subsampling and DNA extraction

Unless otherwise stated in the precious sections, DNA extraction was performed as previously described77. The sample containers were thawed at 4 °C and dried soil samples were rehydrated using phosphate-buffered saline before subsampling. The sample material was divided into a total of three Matrix 1.2 ml 2D barcoded tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Of the three 2D Matrix tubes only one was prefilled with the lysing matrix E (MP Biomedical), to which 100 µl of sample material was added. For the two other tubes, 800 µl of sample material was added and deposited at −20 °C in the MFD biobank. The tubes destined for downstream DNA extraction were added to a 96-well SBS rack containing 4 empty positions, 4 reaction blanks and 1 extraction positive control (https://github.com/SebastianDall/HT-Downscaled-Illumina-Metagenomes-Protocol). Linkage of the linear barcodes of the original sample container, the 2D Matrix tubes and location in the final SBS racks was ensured with the use of a Mirage Rack Reader (Ziath) and the software DataPaq (Ziath) forwarding the entries to an SQL server (MongoDB). Pseudolinks were generated for samples acquired as DNA extracts.

DNA extraction was performed using slightly modified protocol of the DNeasy 96 PowerSoil Pro QIAcube HT Kit (QIAGEN). In total, 500 µl CD1 was added to each 2D barcoded Matrix tube; the samples then underwent three 1,600 rpm bead-beating cycles performed at 2-min intervals using the FastPrep-96 (MP Biomedicals). Between the cycles, the samples were kept on ice for 2 min. After lysis, the samples were centrifuged at 3,486g for 10 min using an Eppendorf 5810 benchtop centrifuge (Eppendorf). Then, 300 µl supernatant was transferred by hand to a new S-block containing 300 µl CD2 and 100 µl nuclease-free water (NFW) to meet the requirement of 700 µl for the remaining part of the protocol. The samples were mixed by pipetting and centrifuged at 3,486g for 10 min; the sample transfer step was then performed using the QIAcube HT. All of the subsequent steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA was quantified using the Qubit 1× HS assay (Invitrogen). Extraction metadata, including a denotation of methodology, can be found in Supplementary Data 6.

MFD ontology

For the MFD data, habitat classification was performed on site by experts in accordance with the relevant field guides when available for the habitats (that is, the natural habitats from macrobial ontologies). Habitat classification was therefore performed by checking the presence of plant indicator species, topographic and abiotic conditions. The MFDO was developed as a link between the classical plant-derived habitat ontologies and the Earth Microbiome Project Ontology (EMPO). The broadest MFDO classification level (Sample type), corresponds to the most specific EMPO level (EMPO level 4)3, while the detailed levels for natural samples correspond broadly to the Natura 2000 habitat ontology8. Finally, missing categories, such as urban, were adapted from the EUNIS ontology9 to provide a detailed description of non-natural habitats. The MFDO was designed, for the moment, to fit the Danish environment and it was refined with a panel of national experts. The full MFDO and its association to other habitat ontologies (that is, EMPO, Natura 2000 and EUNIS) can be found at GitHub (https://github.com/cmc-aau/mfd_metadata).

Metadata curation

The metadata collected with codeREADr were screened for completeness in the following fields (hereafter, minimal metadata): fieldsample_barcode (the unique sample identifier), project_id (unique identifier of the subproject), longitude and latitude (ISO 6709), sitename (common name of the sampling site), coords_reliable (indicating if the coordinates are reliable, not reliable or masked), sampling_date (sampling date ISO 8601) and five levels of the MFD habitat ontology (mfd_sampletype, mfd_areatype, mfd_hab1, mfd_hab2, mfd_hab3). If a sample presented an incorrect entry, (for example, wrong format, not meaningful for that column or unreadable), the error was corrected using R78 v.4.2.3, and if a correction was not possible, or the entry absent, the responsible person for the subproject was contacted. The process was iterated until improvements were not possible anymore. In brief, common corrections included case changing, date formatting (using lubridate79, v.1.9.2) and coordinate projection (project function from terra80, v.1.7.55). The reference grid mapping and masking of the coordinates were performed using the terra80 v.1.7.55 package. The European Environment Agency 1-km (ref. 81) and 10-km (ref. 82) reference grids of Denmark were projected from EPSG:3035 to EPSG:4326 (function project), whilst the coordinates from MFD samples were encoded into a spatial vector (function vect) and mapped onto the grids (function intersect) to identify their cells of origin. The cells associated with each sample (when the coordinates were present), were reported in the fields cell.1 km and cell.10 km of the metadata. The centroids of the cells were computed (function centroids) and, in the case of samples from subprojects P04_3 and P04_5, the centroids were provided as latitude and longitude, while the coords_reliable field for those samples was set to ‘Masked’. Coordinates from subproject P06_3 were provided already masked as generic locations in the commune of sampling. Concordance between manual annotation of the habitat and government-registered LU (land use) designation was inferred comparing the MFDO for each sample with the Basemap04 (ref. 10) aggregated LU map. A broad correspondence of terms between MFDO and LU terms was established and, to account for GPS and labelling inaccuracies, any match in a range of 20 m was considered in concordance. Samples that were in disagreement were screened manually on Google Maps and, if the disagreement was confirmed, the coords_reliable field was set to ‘No’. For Fig. 1, the base map was from EuroGeographics. This dataset includes Intellectual Property from European National Mapping and Cadastral Authorities and is licensed on behalf of these by EuroGeographics. The original dataset is available for free online (https://www.mapsforeurope.org). Terms of the licence are available at https://www.mapsforeurope.org/licence. All attribution statements can be found online (www.mapsforeurope.org/attributions). For Extended Data Fig. 1, the base of the map is from Eurostat (Geodata, GISCO, Eurostat; https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata).

Short-read metagenomic library preparation, sequencing and processing

Metagenomic libraries were prepared with a 1:10 reagent volume reduction of the standard Illumina DNA prep protocol (Illumina) as described previously77. Using the I.DOT One (DISPENDIX), 3 µl of up to 20 ng template DNA was prepared before addition of 2 µl BLT/TB1 and subsequent incubation in a thermocycler at 55 °C for 10 min. Tagmentation was stopped by addition 1 µl TSB using the I.DOT One, and incubation in the thermocycler at 37 °C for 15 min. The tagmented DNA was washed twice with 10 µl TWB. The I.DOT One was used to add the PCR master mix, prepared by mixing 2 µl EPM and 2 µl NFW per reaction. The epMotion 96 (Eppendorf) was used to add 1 µl IDT Illumina UD index (Illumina) to each reaction well. The input of genomic DNA was used to determine the applied cycles of the BLT-PCR program: 7 (4.9–20 ng), 8 (2.5–4.9 ng), 10 (0.9–2.5 ng) or 14 (< 0.9 ng). Size-selection was performed on the libraries by addition of 17 µl NFW, before 18 µl of the reaction volume was transferred to a new PCR-plate together with a mixture of 16:18 µl SPB:NFW. After incubation, 50 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a new PCR-plate with 6 µl undiluted SPB. After incubation, the beads were washed twice with 45 µl 80% ethanol and eluted in 20 µl NFW. SPB are 1:1 interchangeable with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA).

The individual libraries were quantified using a 1:10 diluted upper standard. The pooled libraries were concentrated using 2× volume of SPRI ProNex Chemistry (Promega) beads. Final sequencing libraries were produced by an equimolar combination of the pooled libraries. Quality control was performed using the Qubit 1× HS assay (Invitrogen) and DS1000 or DS1000 HS ScreenTape (Agilent Technologies). Library metadata are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Metagenomic libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform to a median depth of 5 Gb. If a library yielded insufficient data, the library was either repooled or reprepared for a second round of sequencing. The Illumina data were demultiplexed using bcl2fastq2 v2.20.0 (Illumina). The raw reads were trimmed for barcodes, quality filtered and deduplicated with fastp83 v.0.23.2 with the following options: --detect_adapter_for_pe --correction --cut_right --cut_right_window_size 4 --cut_right_mean_quality 20 --average_qual 30 --length_required 100 --dedup --dup_calc_accuracy 6. Commands were parallelized using GNU-parallel84 v.20220722 and outputs compressed using pigz85 v.2.4. Sequencing metadata are provided in Supplementary Data 6.

Nearly full-length bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplicon library preparation, sequencing and processing

A representative set of 426 samples were selected for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing. These samples comprise 130 samples from the BIOWIDE project (P01_1)31, as well as 295 samples manually selected to reflect the sample diversity in the full dataset while attempting to maintain the geographical coverage. From samples from subterranean sediments (P12_1), the input DNA was pooled based on the sediment core the samples were derived from. From 14 of the samples, we failed to generate data of sufficient quality leading to a dataset of 412 samples. Here PCR was used to amplify the region V1–V8 of the 16S gene using UMI-tagged target primers enabling downstream chimera filtering and error-correction similar to the method described previously11. All of the samples were tagged by the UMI-tailed target primers lu_16S_8F and lu_16S_1391R in a PCR reaction (Supplementary Data 7). The reaction contained 10–20 ng DNA input, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of each primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. The PCR program consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 2 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (55 °C for 1 min) and extension (72 °C for 5 min). The PCR products were then purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) at a ratio of 0.7× beads per sample. After 5 min of incubation, the beads were washed twice in 80% ethanol and eluted in 18 µl NFW for 5 min. The tagged molecules were then amplified in a second 25 cycle PCR reaction using barcoded primers targeting the UMI-adapter sequence. The PCR reaction contained 15 µl of the purified eluate, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of forward and reverse primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. The PCR-program consisted of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 15 s), annealing (60 °C for 30 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) as described above and eluted in 20 µl NFW. Poorly performing samples underwent a third PCR reaction with 5–10 cycles using up to 50 ng amplicon DNA as input and otherwise identical to the previous PCR reaction.

The barcoded amplicons were multiplexed in pools of 5–6 samples containing a total of 300 ng. The pools were used as input for library preparation for DNA sequencing using the ‘Amplicons by Ligation (SQK-LSK110)’ protocol (version: ACDE_9110_v110_revG_10Nov2020) and loaded onto a MinION R.9.4.1 flow cell (FLO-MIN106D). The flow cells were sequenced for up to 72 h on a GridION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) using the MinKNOW software v.21.05.8 and basecalled using the super-accurate model (r941_min_sup_g507) with Guppy v.5.0.11. Downstream consensus sequences were generated using the longread_umi pipeline v.0.3.2 described previously11 with slight modifications to ensure compatibility with the updated medaka model (r941_min_sup_g507) and the custom barcode sequences. The quality of the consensus sequences was evaluated based on a ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community DNA Standard (Zymo Research, D6306) included together with the samples. With UMI sequence coverage of ≥7× corresponding to Q30+ and ≥14× to Q40+. The exact command used to generate the consensus sequences was: longread_umi nanopore_pipeline -d input.fq -v 10 -o analysis -s 140 -e 140 -m 1000 -M 2000 -f GGAATCACATCCAAGACTGGCTAG -F AGRGTTYGATYMTGGCTCAG -r AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC -R GACGGGCGGTGWGTRCA -c 3 -p 2 -q r941_min_sup_g507 -t 20 -T 2 -U “3;2;6;0.3”.

Bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA gene operon library preparation, sequencing and processing

A representative set of 450 samples was selected for both bacterial and eukaryotic rRNA operon sequencing. These samples are the same as those selected for 16S rRNA UMI amplicon sequencing. However, all extracted DNA had been used up for 8 of the samples, resulting in an overlap of only 404 samples, which is why we included 46 other samples. For bacterial rRNA sequencing, PCR was used to amplify around 4,500 bp targeting the 16S and 23S gene using the primers MFD_16S_8F and MFD_23S_2490R (Supplementary Data 7). For eukaryotic rRNA, operon sequencing PCR was used to amplify around 4,500 bp targeting the 18S and 28S gene using the primers MFD_18S_3NDF and MFD_28S_21R (Supplementary Data 7). The PCR reactions contained 10–20 ng DNA input, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of each primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. With the addition of 1× SuperFi GC enhancer when amplifying the eukaryotic rRNA operons. The PCR-program consisted of initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min followed by 25 cycles of denaturation (98 °C for 15 s), annealing (55 °C for 15 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were then purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) at a ratio of 0.7× beads per sample. After 5 min of incubation, the beads were washed twice in 80% ethanol and eluted in 20 µl NFW for 5 min. The amplicon DNA was barcoded in a second 8–10 cycle PCR reaction using barcoded primers targeting the introduced adapter sequence. The PCR reaction contained 20 ng of the purified amplicon DNA, 1× SuperFi buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 500 nM of forward and reverse primer and 2 U of Platinum SuperFi DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) in a total volume of 50 µl. With the addition of 1× SuperFi GC enhancer when amplifying the eukaryotic rRNA operons. The PCR program consisted of initial denaturation at 98 °C for 1 min followed by 8–10 cycles of denaturation (98 °C for 15 s), annealing (60 °C for 15 s) and extension (72 °C for 3 min), followed by a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The PCR products were purified with CleanNGS SPRI beads (CleanNA) as described above and eluted in 18 µl NFW.

The barcoded amplicons were multiplexed in pools of 92 samples containing a total of 1–2 µg of DNA. The pools were size-selected using SPRI ProNex Chemistry (Promega) with a ratio of 1.2× beads per sample according to the manufacturer’s protocol and eluted in 125 µl. The size-selected and purified pools were shipped for PacBio CCS sequencing on the Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences) using the binding kit 3.2. The CCS sequences were further processed using Lima v.2.6.0 (Pacific Biosciences) to filter and demultiplex the data. This was done using the hifi-preset ASYMMETRIC and the following settings --min-score 70, --min-end-score 40, --min-ref-span 0.75, --different, --min-scoring-regions 2. Furthermore, remaining ligation products were removed by identifying partially remaining adapter sequences after filtering. Subsequently all reads were oriented while removing primer sequences and filtering reads below 3.5 kb or above 6.5 kb using cutadapt86 v.3.4. 16S rRNA genes corresponding to the V1–V8 region were extracted from the rRNA operons using a custom script (trim_RNA_operons.sh) that carries out several steps: first, the rRNA operons were truncated to 1,450 bp using the usearch87 v.11 command fastx_truncate -trunclen 1450. The trimmed sequences were then trimmed based on the 1391R88 (Supplementary Data 7) primer using cutadapt86 v.3.4. The sequences for which the primer could not be found were aligned to the global SILVA v.138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19) alignment using SINA89 v.1.6.0, the aligned sequences were trimmed according to the position of the primer binding sites in the alignment. Truncated sequences were removed using a custom script (remove_incomplete_seqs_from_sina_aln.py) that considered sequences that start or end with three or more gaps as truncated. Finally, gaps were removed using the custom script (Remove_gaps_in_fasta.py), whereafter the primer- and alignment-trimmed sequences were combined.

Before diversity analysis, 18S rRNA genes, corresponding to the position between the 3NDf90 and 1510R91 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7), were extracted using a custom script (trim_euk_RNA_operons_3ndf-1510R.sh). This script was identical to the script used for processing bacterial rRNA operons except that sequences were trimmed based on the 1391R88 primer (Supplementary Data 7) with cutadapt86 v.3.4 and the alignment trimmed based on the corresponding position in the SILVA19 global alignment using SINA89 v.1.6.0. The resulting reads were dereplicated using usearch87 v.11 command usearch -fastx_uniques -sizeout and then resolved into ASVs using usearch -unoise3 -minsize 2. The phylogenetic diversity of the 18S rRNA genes was determined by clustering the ASVs into OTUs at 99% identity with usearch -cluster_smallmem -maxrejects 512 -sortedby other, followed by mapping against the PR2 (ref. 16) database to determine the percentage identity with the closest hit in the database using usearch -usearch_global -maxrejects 0 -maxaccepts 0 -top_hit_only -id 0 -strand plus. An OTU-table was created by mapping the trimmed raw reads against the 99% OTUs using usearch -otutab -otus. Taxonomy was assigned to the OTUs using the UTAX version of the PR2 database16 v.5.0.0, the SINTAX classifier through usearch63,87 v.11. For 18S diversity analyses, the taxonomy was inferred with the DADA2 (ref. 92) v.1.26.0 function assignTaxonomy. OTUs not classified as Eukaryota were discarded before the downstream analyses.

Estimation of the Danish terrestrial diversity

The nearly full-length 16S rRNA UMI gene sequences were mapped against the nearly full-length OTUs clustered at 98.7% sequence similarity to yield a dataset (OTU table) with 412 habitat-representative samples and 107,826 (106,760 after filtering) species-representative OTUs using usearch87 v.11 with downstream analysis done in R78 v.4.4.1 using tidyverse93 v.2.0.0. Similarly, the full-length 18S rRNA gene sequences were mapped against the nearly full-length OTUs clustered at 99% sequence similarity, yielding a dataset of 450 habitat-representative samples and 12,515 (12,469 after filtering) species-representative OTUs.

We made habitat-specific rarefaction curves across samples with more than 4,000 observations from habitats with more than 9 sample representatives (5.9 million observations), as well as a pan-habitat rarefaction curve (6.0 million observations) from the nearly full-length bacterial rRNA gene UMI dataset. For this analysis, we combined the samples from temperate heath and scrub (n = 12) and sclerophyllous scrub (n = 7). Likewise, we made habitat-specific rarefaction curves across samples with more than 6,000 observations from habitats with more than 9 sample representatives (12.0 million observations), as well as a pan-habitat rarefaction curve (12.9 million observations) from the eukaryotic nearly full-length 18S rRNA gene dataset. For this analysis we combined the samples from temperate heath and scrub (n = 13) and sclerophyllous scrub (n = 7). Rarefaction was performed using vegan94 v.2.6-6-1 (function rarecurve) using a step size of 10,000.

Sample based coverage and Hill diversity indices were calculated after transformation to presence and absence data by using rarefaction and extrapolation with Hill numbers of order q as implemented in the iNEXT95 v.3.0.1 package (function iNEXT). Hill richness (total number of species), Hill–Shannon (number of common species) and Hill–Simpson (number of dominant species) were estimated using order q = 0, q = 1 and q = 2, respectively. For the total dataset, the end point of extrapolation was set to twice the size of the dataset (nBac = 824, nEuk = 900); and, for habitat-specific estimates, the end point was fixed at 100 samples. For the habitat-specific data, we investigated normality (function shapiro_test) of the community coverage and log-transformed sampling effort and, based on the results, measured the linear correlation with the Pearson correlation coefficient (function cor_test) using the package rstatix96 v.0.7.2.

Establishment of the MFG 16S rRNA gene reference database

The MFG 16S rRNA reference database was assembled from high-quality bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA genes obtained from several sources: nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene and rRNA operon amplicons created in this study, SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19), EMP500 (ref. 3), AGP70 (ref. 11), MiDAS 4 (ref. 97) and MiDAS 5 (ref. 20), and ref. 21. All bacterial sequences were trimmed between the 8F98 and 1391R99 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7), and archaeal sequences between the 20F100 and the SSU1000ArR101 primer-binding sites (Supplementary Data 7).

High-quality bacterial and archaeal sequences were obtained from the SILVA v138.1 SSURef NR99 (ref. 19) ARB-database by exporting them separately in the fastawide format after terminal trimming between positions 1,044 and 41,788 (Bacteria) and positions 1,041 and 32,818 (Archaea) in the global SILVA19 alignment, corresponding to the primer binding sites (Supplementary Data 7). A custom script (Extract_full-length_16S_rRNA_genes_from_SILVA_alignments.sh) was used to remove truncated sequences based on the presence of terminal gaps in the exported FASTA-alignments. Finally, sequences that contained N’s were removed and U’s were replaced with T’s using two custom scripts (Remove_seqs_with_Ns.py and replace_U_with_T.py).