Main

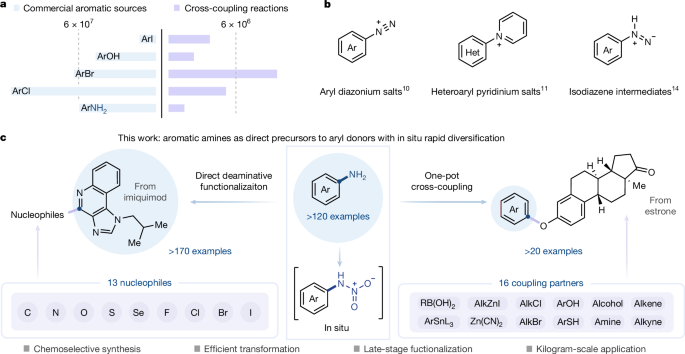

For decades, aryl halides and phenols have dominated as privileged arylating agents5,6, serving as fundamental building blocks for transformations such as transition-metal-catalysed cross-coupling reactions (Fig. 1a). By contrast, aromatic amines—structural cornerstones of natural products and medicinal compound libraries7,8—remain severely under-used as reactive species. Although stepwise functionalization strategies emerged as early as 1884 with the copper-mediated Sandmeyer reaction via diazonium intermediates, subsequent developments expanded this reactivity largely through free-radical pathways3,9. In general, conventional diazotization protocols require the use of explosive diazonium salts, introducing safety concerns. Accordingly, the Ritter group devised an elegant safer varianet of the Sandmeyer reaction that generates transient aryldiazonium through nitrate-reduction chemistry (Fig. 1b)10. However, these aryldiazonium-based processes still suffer from stoichiometric copper consumption and restrictive substrate compatibility. The Cornella group recently disclosed an innovative deaminative strategy in which electron-deficient (hetero)aromatic systems, following in situ generation of pyridinium intermediates, undergo substitution via an SNAr pathway11,12. In parallel, the Levin group demonstrated a promising radical-based deamination approach that uses anomeric amide reagents to generate carbon-centred radical species13,14. Yet these reactions often rely on reagents with poor atom economy and are typically restricted to either electron-deficient or -rich aromatic systems, thereby limiting their broader applicability. Building on these advances, we set out to investigate whether an alternative activation mode could enable direct deaminative functionalization and thus provide access to previously unexplored reaction manifolds.

a, Relative commercial availability of common aryl donors used in cross-coupling reactions (data retrieved from the Reaxys database). b, Recent advances in deaminative functionalization of aromatic amines10,11,14. c, Aromatic amines as direct precursors to aryl donors with in situ rapid diversification (this work). Het., heterocycle.

Our direct deaminative strategy makes use of the distinct reactivity of N-nitroamines through nitric acid-mediated extrusion of nitrous oxide (N2O), enabling direct conversion of aromatic C−N bonds into an array of C−X (C−Br, C−Cl, C−I, C−F, C−N, C−S, C−Se, C−O) and C−C bonds. This approach establishes a route for one-pot deaminative cross-couplings that merges deaminative functionalization with transition-metal-catalysed arylation, offering expeditious access to complex pharmacophores from ubiquitous aromatic amine precursors under mild conditions (Fig. 1c). Moreover, the process is readily scalable to kilogram-scale synthesis.

Reaction development

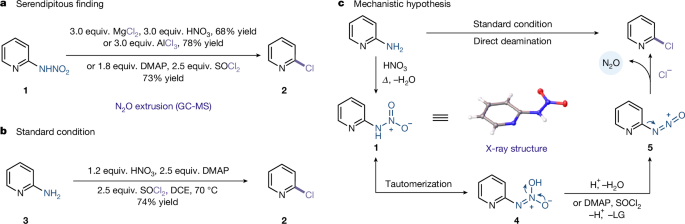

The direct substitution of amino groups within aromatic frameworks presents a formidable synthetic challenge due to the poor leaving-group capability of NH2 moieties2,15. Building on established deamination strategies for prefunctionalized aliphatic amines16,17,18, we hypothesized that installing dual electron-withdrawing groups (for example, acyl, sulfonyl) on the amino group could substantially weaken the C(sp2)−N bond, thereby promoting subsequent nucleophilic substitution. In pursuit of suitable precursors for this transformation, we synthesized various substrates bearing different electron-withdrawing groups on the amino group (trifluorosulfonyl-, acetyl-, benzoyl- and so on; see Supplementary Section 3 for full details). Unfortunately, these substrates proved ineffective in our initial investigations; our exploration thus shifted towards introducing two nitro groups via the nitration process, which unexpectedly led us to the identification of N-pyridylnitroamine 1 and N-(4-cyanophenyl)nitroamine S122, which were presumably formed through the dehydration of aromatic amines with nitric acid (see Supplementary Section 7.1 for full experimental details). The structures of these compounds were elucidated through X-ray crystallographic analysis (Supplementary Figs. 41–43). Despite their earliest discovery in 189319,20,21, the reactivity potential of heteroaromatic and aniline-derived nitroamines have remained largely unexplored.

A pivotal discovery emerged when N-pyridylnitroamine was treated with magnesium chloride/nitric acid, aluminium trichloride, or thionyl dichloride, each of which efficiently yielded the deaminative chlorination product 2 (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Mechanistic studies unveiled an unprecedented N2O extrusion pathway accompanying this transformation, as confirmed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. 25–28). This serendipitous result uncovered an operationally mild protocol for the deaminative chlorination of aminoheterocycles. The observed reactivity motivated us to streamline the process. We envisioned a practical protocol that involves the in situ generation of reactive N-nitroamine intermediates through nitric-acid-mediated nitration of aromatic amines, followed by tandem deaminative chlorination, thereby eliminating the need for nitroamine isolation. Indeed, we successfully detected the formation of N-pyridylnitroamine upon the exposure of 2-aminopyridine to nitric acid (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). After an extensive optimization, subjecting 2-aminopyridine to just 1.2 equivalents of nitric acid under the optimized conditions successfully afforded the corresponding chlorination product 2 in good yield (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Figs. 3–10). These results suggest that the deamination process is initiated by the formation of N-pyridylnitroamine (1). It is worth noting that 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) is critical for increasing the efficiency of this reaction, probably due to its dual role as a base and as an activator of SOCl2, thereby facilitating the generation of nucleophilic chloride anions. Next we conducted kinetics experiments, which suggest that the formation of the N-nitroamine intermediate might be the rate-determining step (Supplementary Figs. 18–22). Notably, direct exposure of preformed nitroamines to chlorination conditions resulted in complete conversion within 1.5 min. These findings support our hypothesis that the N-nitroamine might act as a transient intermediate that, once formed, rapidly collapses to the final product.

a, Unexpected finding. b, Standard conditions. c, Mechanistic hypothesis. See Supplementary Section 3 for full experimental details. LG, leaving group.

Building on these observations, a plausible mechanistic hypothesis for the deaminative process is depicted in Fig. 2c. The sequence initiates with the nitration of the aromatic amine to form an N-nitroamine 1, which undergoes tautomerization to generate intermediate 4. Following treatment with the appropriate reagents, this species is converted to a labile intermediate 5. Intermediate 5 then extrudes N2O and is subsequently intercepted by a nucleophile, thereby delivering the deaminative functionalization product and driving the reaction to completion.

Substrate scope exploration

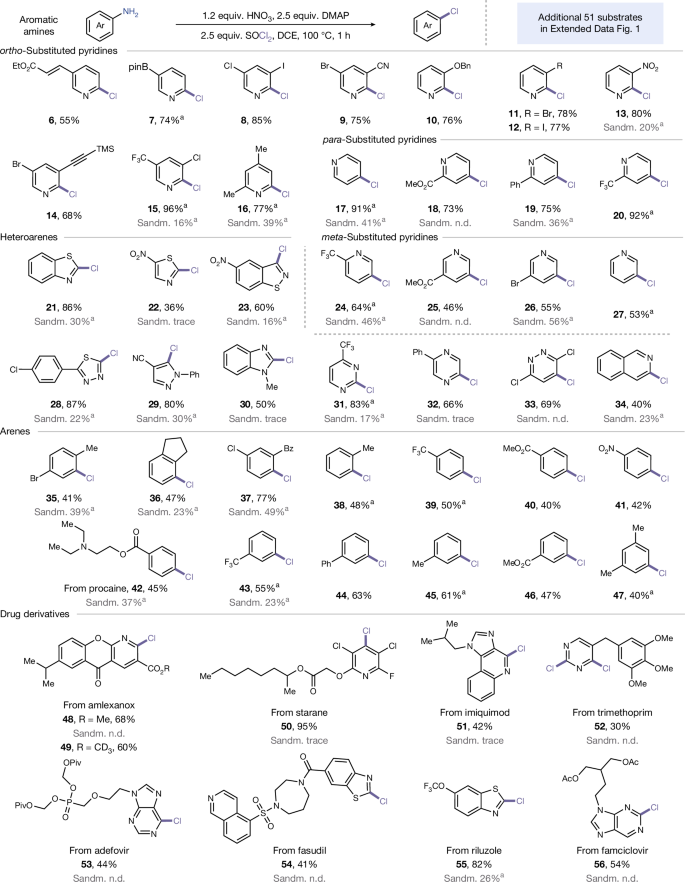

With the established deaminative chlorination procedure in hand, we systematically explored its generality. This transformation demonstrates exceptional versatility across a diverse range of medicinally relevant aminoheterocyclic scaffolds. As depicted in Fig. 3, both ortho- and para-aminopyridines bearing electronically varied substituents—including trifluoromethyl, nitro, cyano, ester, halogen, ether, phenyl and alkyl groups—underwent successful conversion to provide the corresponding chlorinated products in moderate to good yields (6–20, 55–96% yield). Notably, the protocol accommodates synthetically valuable functional handles such as alkenes (6), alkynes (14) and aryl boronates (7), which are particularly advantageous for downstream derivatization. A long-standing challenge in deaminative halogenation has been the functionalization of meta-aminopyridines, which typically suffer from poor reactivity under conventional conditions10,11,14. We found that our methodology successfully addresses this limitation, enabling efficient chlorination of meta-aminopyridines (24–27, 46–64% yield). The scope further extends to five-membered heteroaromatic amines, including thiazole, isothiazole and 1,3,4-thiadiazole, delivering chlorinated products with useful levels of efficiency (21–23, 28; 36–87% yield). Moreover, multinitrogen-containing heterocycles, such as pyrazole, imidazole, pyrimidine, pyrazine and pyridazine, were all well-tolerated (29–33, 50–83% yield). The protocol is also compatible with fused polycyclic aromatics (34, 40% yield). Comparative studies with classical Sandmeyer conditions revealed the superior performance of our protocol, particularly in multi-nitrogen systems. Although conventional copper-mediated aryldiazonium-based chemistry typically results in low (often undetectable) yields, our approach reliably achieves satisfactory efficiency (Fig. 3, grey highlights). This enhanced reactivity is attributed to our unique mechanistic pathway, which circumvents traditional radical intermediates. This deaminative transformation exhibits good electronic tolerance and positional generality, enabling efficient chlorination of structurally diverse aniline derivatives. The protocol successfully accommodates substituents across the entire electronic spectrum, electron-donating, -neutral and -withdrawing groups at all aromatic positions, furnishing chlorinated arenes in synthetically useful yields (35–47, 40–77% yield).

Given the importance of late-stage functionalization in drug discovery, we explored the applicability of our approach to more structurally complex bioactive molecules. The deaminative chlorination of procaine, a local anaesthetic, proceeded smoothly in a yield of 45% (42), even with the presence of a tertiary amine fragment. Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory agents amlexanox and deuterated-amlexanox yielded the corresponding products in good yields (48, 68% yield; 49, 60% yield). Using starane, an agrochemical, as the substrate, the yield of 50 improved significantly to 95%. Moreover, the fused heterocyclic compound imiquimod, an immunomodulator, was also tolerated, yielding product 51 in 42% yield. Notably, the substrate trimethoprim, an antibacterial bearing two NH2 groups, underwent smooth double deaminative chlorination (52, 30% yield). Chlorination of acid-sensitive, purin-based compounds such as adefovir (anti-hepatitis B) and famciclovir (anti-viral) delivered 53 and 56 in moderate yields. Benzothiazole derivative from fasudil (anti-angina) and riluzole (anti-glutamate) were successfully converted with yields of 41% and 82%, respectively (54 and 55). This performance stands in stark contrast to Sandmeyer conditions, which largely failed for these complex architectures. Our protocol thus represents a robust method for late-stage diversification of drug molecules. An additional 51 examples in Extended Data Fig. 1 further highlight the generality of this protocol.

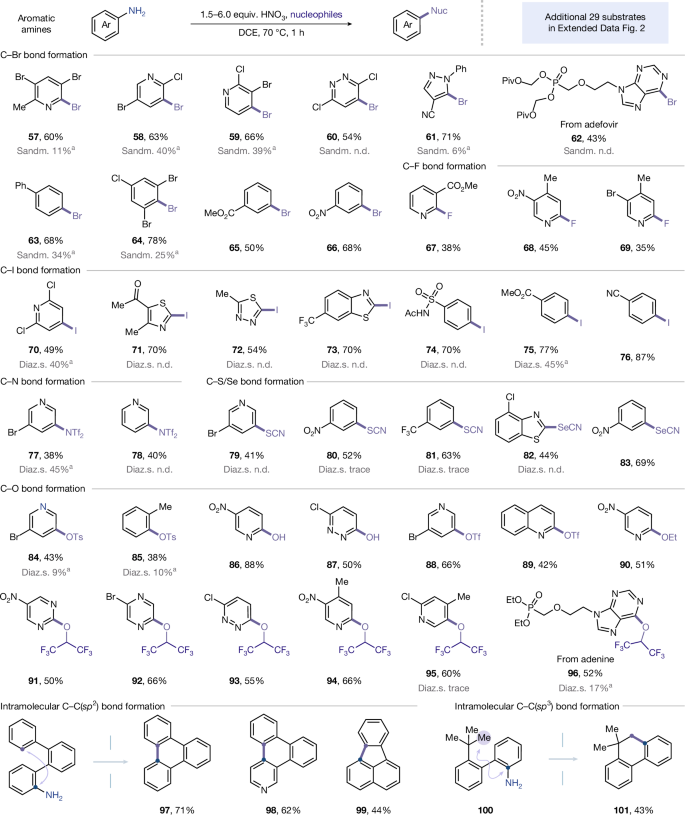

The integration of diverse aromatic amines into chlorination reactions demonstrated the operational efficiency of our deaminative strategy, thus motivating us to systematically explore the reactivity with alternative nucleophiles. We initiated our investigation by exploring a range of deaminative transformations using N-nitroamines (Supplementary Fig. 29). The N-nitroamine intermediates consistently afforded the desired products in good yields, indicating their pivotal role as reactive species in the deamination process. Building on the established protocol for deaminative chlorination, wherein minimal quantities of nitric acid were introduced to activate amino moieties, this strategy exhibited remarkable versatility, enabling facile construction of an array of carbon−heteroatom bonds (C−Br, C−I, C−F, C−N, C−S, C−Se, C−O) and C−C bonds directly from aromatic amines (Fig. 4). Deaminative halogenation proceeded smoothly when using simple halogenation reagents such as SOBr2, LiBr and KI. For example, aromatic amines with five- or six-membered heterocycles, and benzene rings bearing electronically diverse array of functional groups, reacted efficiently to provide the halogenated products (57–66 and 70–76; 43–87% yield). Notably, a range of di- and tri-halogenated aromatic amines proved competent in this transformation (57–60, 64 and 70). No halogen scrambling was observed, which represents a valuable feature with respect to further derivatization. Minor over-halogenated side products were also detected with electron-rich arenes in deaminative halogenation (Cl, Br, I), presumably due to NOx-induced oxidation of halide anions to the corresponding electrophilic equivalents. The incorporation of fluorinated groups into aromatic rings is particularly important, as they can considerably alter their physical and biological properties22. We were delighted to find that 2-aminopyridines successfully underwent deaminative fluorination (67–69, 35–45% yield). We next further examined the compatibility of our new method towards other common nucleophiles. To our delight, the strategy demonstrated versatile engagement with N-, S- and Se-centred nucleophiles, allowing access to a broad array of chemical diversity (77–83, 38–69% yield). However, the current nucleophile scope remains limited for species with low basicity. Significantly, the protocol proved productive in C−O bond formation, demonstrating its potential for facilitating further cross-coupling reactions and late-stage modification of bioactive molecules5,23,24,25. Oxygen-centred reagents—including Ts2O, Tf2O, H2O, EtOH and HFIP—exhibited excellent tolerance with the system, successfully accommodating a wide range of aromatic compounds, including pyridazine, quinoline, pyrazine, pyrimidine, purine, pyridine and benzene derivatives (84–96, 38–88% yield). To comprehensively illustrate the compatibility of this method, several examples were tested under standard aryldiazonium-based conditions. As highlighted in Fig. 4, most cases provided significantly lower yields (often undetectable) compared with our protocol. The construction of carbon–carbon bonds is pivotal in organic synthesis and industrial production26. Encouraged by the preceding outcomes, we extended the scope to C-nucleophiles. Importantly, the direct use of C(sp2)−H or C(sp3)−H bonds as latent nucleophiles enabled streamlined access to both C(sp2)−C(sp2) and C(sp2)−C(sp3) bonds, potentially accelerating the synthesis of a myriad of organic compounds (97–99, 101, 123 and 125; 40–71% yield). A further 29 examples for this deaminative functionalization are detailed in Extended Data Fig. 2. The bar graph in Extended Data Fig. 3 demonstrates an enhanced yield of our method for several representative substrates over conventional Sandmeyer or diazonium salt pathways.

Isolated yields. aYield (1H NMR). See Supplementary Sections 4–6 for the full experimental details. General halogenation conditions: amine (0.5 mmol), SOBr2 (1.25 mmol) as a bromine source, HNO3 (2.0 equiv.), DMAP (2.5 equiv.), DCE (5.0 ml), 70 °C, 1 h; amine (0.5 mmol), KI (2.0 mmol) as an iodine source, HNO3 (6.0 equiv.), DCE (5.0 ml), 70 °C, 1 h; amine (0.2 mmol), AgF2 (0.6 mmol) as a fluorine source, HNO3 (3.0 equiv.), DCE (2.0 ml), 70 °C, 2.5 h. Nuc, nucleophiles; Piv, pivaloyl; Ph, phenyl; Ac, acetyl; Tf, trifluoromethanesulfonyl; Ts, tosyl; Sandm., Sandmeyer conditions; Diaz.s., diazonium salts; n.d., not detected.

One-pot strategy and application

We sought to improve operational simplicity further by developing a one-pot deaminative cross-coupling sequence. This makes use of in situ-generated aryl (pseudo)halides in subsequent transition-metal-catalysed coupling or nucleophilic substitution reactions without the need for intermediate isolation, enhancing its synthetic usefulness. Although there have been some instances of one-pot cross-coupling protocols27,28, methods with broad applicability are still lacking.

The deaminative halogenation products require no purification and could be directly subjected to cross-coupling reactions by simply adding the appropriate coupling reagents under standard transition-metal catalysis (102–108, 38–52% yield) (Extended Data Fig. 4). Notably, a range of transformations—including Negishi coupling (102), reductive cross-coupling (104), Ullmann–Ma reaction (105), Buchwald–Hartwig amination (106), Hirao reaction (107), and sulfonylation (108)—were all compatible with this one-pot deaminative cross-coupling sequence29,30,31,32,33,34. Furthermore, metallaphotoredox catalysis35 was successfully integrated into the one-pot sequence, delivering azetidine product 103. A further 16 examples using other coupling reagents are detailed in Extended Data Fig. 5. The broad compatibility of this one-pot protocol with diverse transition-metal-catalysed couplings, and its good tolerance towards multifunctional coupling partners, offers distinct retrosynthetic disconnections for the expedient synthesis of complex molecules from widely available native functionalities, thereby underscoring its significance for advancing medicinal chemistry. Encouraged by these results, we also initiated a preliminary exploration into direct deaminative cross-coupling and were pleased to achieve a direct deaminative Suzuki coupling (109, 47% yield) of aromatic amines.

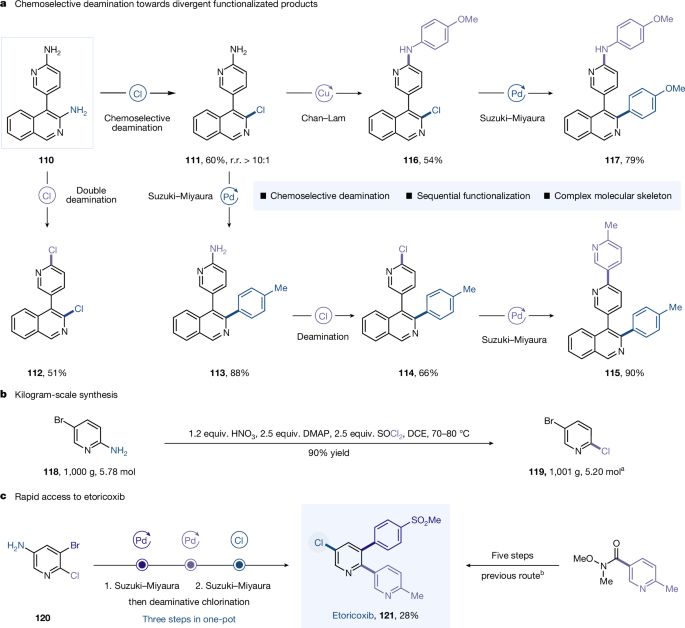

To further showcase the applicability of this method, we explored its capacity to efficiently construct drug-like molecular complexity in a highly expedient yet modular fashion through chemoselective, sequential deaminative functionalization (Fig. 5a). To this end, compound 110, which contains two NH2 groups of similar reactivity, was chosen as the starting material. Encouragingly, deaminative chlorination occurred at the isoquinolinyl aromatic ring, delivering mono-chlorinated product 111 in 60% yield with high regioselectivity by simply controlling the reaction temperature. Interestingly, increasing the amount of chlorinating reagents smoothly facilitated a double deaminative chlorination to product 112 in 51% yield. Subjection of the resulting chloride 111 to a stepwise Chan–Lam coupling followed by a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling afforded the diarylation product 117. Alternatively, treatment of 111 under Suzuki–Miyaura coupling conditions followed by our newly developed deaminative cross-coupling sequence provided the drug-like compound 115 with good efficiency. Remarkably, the reaction of the substrate 5-bromopyridin-2-amine (118) was successfully scaled up to 1 kg, yielding the product 119 in a high yield of 90% with simple recrystallization (Fig. 5b). This operational robustness offers distinct industrial advantages, particularly for discovery chemistry and process development across other industries36.

a, Chemoselective deamination towards divergent synthesis of complex molecules. b, Kilogram-scale synthesis. c, Efficient synthesis of etoricoxib. aThe product was purified by simple recrystallization. bSee ref. 37 for the previous route. All yields are isolated. See Supplementary Section 8 for full experimental details. r. r., regioselective ratio.

Moreover, our one-pot methodology enables streamlined synthesis of multifunctional (hetero)arenes but typically necessitates overcoming multiple challenges, including the electronic and steric properties of electrophiles and nucleophiles, choice of catalysts, ligands, additives and solvents. We then investigated the selective and sequential functionalization of three sites on a pyridine ring. The iterative conversion of C−Br, C−Cl and C−NH2 bonds in a commercially available starting material was achieved successively37 to deliver etocoxib 121 in a three-step, one-pot operation with a synthetically useful yield of 28% (Fig. 5c).

Mechanistic studies

On the basis of our proposed mechanism (Fig. 2c), we conducted a series of experiments to gain some mechanistic insights into the key product-forming step of this deaminative transformation (see Supplementary Section 3 for full experimental details). Whether the transformation proceeds through an aryl cation intermediate38,39 or a direct nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) pathway remains a subject of ongoing discussion. Past literature has extensively documented the Mascarelli-type reaction as a classical example of intramolecular C–H insertion mediated via aryl cation intermediates40. Notably, substrates 100 and 122 underwent smooth deamination, yielding the corresponding C−H insertion products in 43% and 40% isolated yields, respectively. Furthermore, treatment of substrate 124 under nitric acid conditions afforded intramolecular electrophilic substitution product 125 in 60% yield. These initial results support the possible formation of aryl cation intermediates during the reaction (Extended Data Fig. 6a). We then performed further experiments to investigate the nature of the reactive species. ortho-n-Butyl aniline 126 underwent intramolecular C–H insertion in ethyl acetate under nitric acid conditions, affording the deaminative cyclization product 127, whereas selective deaminative arylation product 128 was obtained when benzene was used as solvent (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Alternatively, when meta-n-butyl aniline was used as the precursor under identical conditions, arylation product was obtained in 36% yield, probably occurring through an electrophilic aromatic substitution process (Supplementary Fig. 32). These findings further corroborate the intermediacy of aryl cations in these transformations39. Moreover, under Ritter-type conditions, the formation of deaminoamidation product 130 provides additional support for the aryl cation intermediate acting as the key electrophilic species (Extended Data Fig. 6c). A Hammett analysis was also conducted with a series of para-substituted aniline derivatives under standard deaminative chlorination conditions. Plotting log(kX/kH) against the substituent parameter σ resulted in a linear correlation with the negative slope (ρ = −0.229), consistent with the proposed aryl cation intermediate in the transition state (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Although these results collectively support the involvement of aryl cation intermediates in the deaminative reaction, we recognize that the electronic properties of the substrates may significantly influence the stability of these intermediates, potentially leading to divergent mechanistic pathways.

We performed density functional theory (DFT) calculations to gain a deeper mechanistic insight (see Supplementary Section 3.8 for full computational analysis; see also Supplementary Figs. 39 and 40). The DFT results suggest that the reaction proceeds through the energetically favoured pathway a, which aligns with experimental observations. As depicted in Extended Data Fig. 6e, loss of chloride anions from intermediate 131 affords intermediate 5, which then undergoes N2O extrusion to form aryl cation 133 (ΔG = 11.1 kcal mol–1). This highly reactive electrophilic species is then captured by nucleophiles to furnish the deaminative functionalization product. Unlike the stable aryldiazonium intermediate, intermediate 5 could not be isolated due to the rapid elimination of N2O. As N2O is a superior leaving group, its extrusion from 5 occurs readily via transition state 132, requiring only 7.3 kcal mol–1 (overall ΔG‡ = 17.0 kcal mol–1). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that a competing SNAr process (pathway b) operates in parallel. It is likely that the reaction mechanism may depend on the nature of the substrate and nucleophile. To investigate this, DFT calculations were performed using seven different nucleophiles (Cl, Br, I, OTf, OCH(CF3)2, SCN, NTf2) across a variety of electronically diverse (hetero)arylamines for both the aryl cation and SNAr pathways (Supplementary Fig. 40). When using strongly electron-deficient aromatic amines in deaminative halogenation (Cl, Br, I), the SNAr pathway via intermediate 134 was favoured over the aryl cation route41. Conversely, in other deaminative functionalizations, the aryl cation mechanism was generally preferred regardless of the electronic nature of the arylamine substrates, including electron-donating (S114), neutral (S117, S118) and electron-withdrawing (S115, S116) substituents.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. The supplementary crystallographic data for this paper are available free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under accession nos. CCDC 2328567 (1), CCDC 2474737 (S120) and CCDC 2474761 (S122). Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/.

References

Ertl, P., Altmann, E. & McKenna, J. M. The most common functional groups in bioactive molecules and how their popularity has evolved over time. J. Med. Chem. 63, 8408–8418 (2020).

Mo, F., Qiu, D., Zhang, L. & Wang, J. Recent development of aryl diazonium chemistry for the derivatization of aromatic compounds. Chem. Rev. 121, 5741–5829 (2021).

Zollinger, H. Reactivity and stability of arenediazonium ions. Acc. Chem. Res. 6, 335–341 (1973).

Firth, J. D. & Fairlamb, I. J. S. Nitrate reduction enables safer aryldiazonium chemistry. Org. Lett. 22, 7057–7059 (2020).

Qiu, Z. & Li, C.-J. Transformations of less-activated phenols and phenol derivatives via C–O cleavage. Chem. Rev. 120, 10454–10515 (2020).

Qiu, G., Lib, Y. & Wu, J. Recent developments for the photoinduced Ar–X bond dissociation reaction. Org. Chem. Front. 3, 1011–1027 (2016).

Brown, D. G. & Bostrom, J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone?. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4443–4458 (2016).

Wang, Y., Haight, I., Gupta, R. & Vasudevan, A. What is in our kit? An analysis of building blocks used in medicinal chemistry parallel libraries. J. Med. Chem. 64, 17115–17122 (2021).

Souza, E. L. S. D. & Oliveira, C. C. Selective radical transformations with aryldiazonium salts. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 26, e202300073 (2023).

Mateos, J. et al. Nitrate reduction enables safer aryldiazonium chemistry. Science 384, 446–452 (2024).

Ghiazza, C., Faber, T., Gómez-Palomino, A. & Cornella, J. Deaminative chlorination of aminoheterocycles. Nat. Chem. 14, 78–84 (2022).

Ghiazza, C., Wagner, L., Fernández, S., Leutzsch, M. & Cornella, J. Bio-inspired deaminative hydroxylation of aminoheterocycles and electron-deficient anilines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202212219 (2023).

Berger, K. J. et al. Direct deamination of primary amines via isodiazene intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 17366–17373 (2021).

Dherange, B. D. et al. Direct deaminative functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 17–24 (2023).

Pang, Y., Moser, D. & Cornella, J. Pyrylium salts: selective reagents for the activation of primary amino groups in organic synthesis. Synthesis 52, 489–503 (2020).

DeChristopher, P. J. et al. Approach to deamination. III. High-yield conversion of primary aliphatic amines into alkyl halides and alkenes via the use of sulfonimide leaving groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 91, 2384–2385 (1969).

White, E. H. The chemistry of the N-alkyl-N-nitrosoamides. II. A new method for the deamination of aliphatic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 77, 6011–6014 (1955).

Berger, K. J. & Levin, M. D. Reframing primary alkyl amines as aliphatic building blocks. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 11–36 (2021).

Bamberger, E. & Storch, L. Das verhalten des diabeneols gegen ferridcyankalium. Ber. 26, 471–481 (1893).

Bamberger, E. Zur kenntniee der nitrirung organiecher basen. Ber. 28, 399–403 (1895).

Daszkiewicz, Z., Spaleniak, G. & Kyzioł, J. B. Acidity and basicity of primary N-phenylnitramines: catalytic effect of protons on the nitramine rearrangement. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 15, 115–122 (2002).

Britton, R. et al. Contemporary synthetic strategies in organofluorine chemistry. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 47 (2021).

Evano, G., Wang, J. & Nitelet, A. Metal-mediated C–O bond forming reactions in natural product synthesis. Org. Chem. Front. 4, 2480–2499 (2017).

Cornella, J., Zarate, C. & Martin, R. Metal-catalyzed activation of ethers via C–O bond cleavage: a new strategy for molecular diversity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 8081–8097 (2014).

Su, J., Chen, K., Kang, Q. & Shi, H. Catalytic SNAr hexafluoroisopropoxylation of aryl chlorides and bromides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302908 (2023).

Nicolaou, K. C., Bulger, P. G. & Sarlah, D. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 4442–4489 (2005).

Dow, N. W. et al. Decarboxylative borylation and cross-coupling of (hetero)aryl acids enabled by copper charge transfer catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 6163–6172 (2022).

Fier, P. S. & Hartwig, J. F. Synthesis and late-stage functionalization of complex molecules through C–H fluorination and nucleophilic aromatic substitution. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 136, 10139–10147 (2014).

Astruc, D. The 2010 chemistry Nobel Prize to R.F. Heck, E. Negishi, and A. Suzuki for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 399, 1811–1814 (2011).

Kim, S., Goldfogel, M. G., Gilbert, M. M. & Weix, D. J. Nickel-catalyzed cross-electrophile coupling of aryl chlorides with primary alkyl chlorides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9902–9907 (2020).

Zhai, Y. et al. Copper-catalyzed diaryl ether formation from (hetero)aryl halides at low catalytic loadings. J. Org. Chem. 82, 4964–4969 (2017).

Buchwald, S. L. & Hartwig, J. F. In praise of basic research as a vehicle to practical applications: palladium-catalyzed coupling to form carbon-nitrogen bonds. Isr. J. Chem. 60, 177–179 (2020).

Jablonkai, E. & Keglevich, G. Advances and new variations of the hirao reaction. Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 46, 281–316 (2014).

Berger, F. et al. Site-selective and versatile aromatic C−H functionalization by thianthrenation. Nature 567, 223–228 (2019).

Zhang, P., Le, C. C. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Silyl radical activation of alkyl halides in metallaphotoredox catalysis: a unique pathway for cross-electrophile coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 8084–8087 (2016).

Sheng, M., Frurip, D. & Gorman, D. Reactive chemical hazards of diazonium salts. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 38, 114–118 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Selective late-stage oxygenation of sulfides with ground-state oxygen by uranyl photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13499–13506 (2019).

Allemann, O., Duttwyler, S., Romanato, P., Baldridge, K. K. & Siegel, J. S. Proton-catalyzed, silane-fueled friedel-crafts coupling of fluoroarenes. Science 332, 574–577 (2011).

Shao, B., Bagdasarian, A. L., Popov, S. & Nelson, H. M. Arylation of hydrocarbons enabled by organosilicon reagents and weakly coordinating anions. Science 355, 1403–1407 (2017).

Allemann, O., Baldridge, K. K. & Siegel, J. S. Intramolecular C–H insertion vs. Friedel–Crafts coupling induced by silyl cation-promoted C–F activation. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 1018–1021 (2015).

Kwan, E. E., Zeng, Y., Besser, H. A. & Jacobsen, E. N. Concerted nucleophilic aromatic substitutions. Nat. Chem. 10, 917–923 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22171049 and 22122104), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant no. LDQ23B020001), the Hangzhou leading innovation and entrepreneurship team project (grant no. TD2022002), the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (YSBR-095) and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. XDB0590000). We thank D. W. C. MacMillan (Princeton University), R. R. Knowles (Princeton University), Y. Liang (AstraZeneca), M. Chen and C. Liu for helpful discussions. We thank H. Wang and B. Zhou from the laboratory of mass spectrometry analysis at Shanghai Institute of Organic chemistry for their support with facility access.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

H.Z., F.Z., X.Z., X.C., G.T. and K.X. are inventors on Chinese patent applications (application nos. CN 2023118572004 and 2024101567075). The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Scott Bagley, Wesley Pein, Susan Zultanski and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Date Fig. 1 Additional 51 substrates as extended scope (deaminative chlorination).

Isolated yields. a1H NMR yield. See Supplementary Information Sections 4–6 for full experimental details. DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; Ph, phenyl; Bn, benzyl; Sandm., Sandmeyer conditions.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Additional 29 substrates as extended scope (deaminative functionalization).

Isolated yields. a1H NMR yield. See Supplementary Information Sections 4–6 for full experimental details. General halogenation conditions: amine (0.5 mmol), SOBr2 (1.25 mmol) as a bromine source, HNO3 (2.0 equiv.), DMAP (2.5 equiv.), DCE (5.0 mL), 70 °C, 1 h; amine (0.5 mmol), KI (2.0 mmol) as an iodine source, HNO3 (6.0 equiv.), DCE (5.0 mL), 70 °C, 1 h. Nuc, nucleophiles; Ph, phenyl; Tf, trifluoromethanesulfonyl; Sandm., Sandmeyer conditions; n.d., not detected.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Improved yields of representative substrates compared to Sandmeyer or diazo methods.

a1H NMR yield.See sections 4–6 for full experimental details. Nuc, nucleophiles; Sandm., Sandmeyer conditions; Diaz.s., diazonium salts; n.d., not detected.

Extended Data Fig. 4 One-pot deaminative cross-coupling reactions.

All yields are isolated. See Supplementary Information Sections 4 and 8 for full experimental details. Boc, tert-butyloxy carbonyl; Ph, phenyl.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Additional 16 examples for one-pot cross-coupling.

All yields are isolated. See Supplementary Information Sections 4 and 8 for full experimental details. Ph, phenyl; Ac, acetyl; tBu, tert-butyl; Boc, tert-butyloxy carbonyl.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Mechanistic studies.

(A) C − H insertion and electrophilic substitution. (B) Control experiments. (C) Ritter-type reaction. (D) Hammett analysis. (E) Proposed mechanism. See Supplementary Information Section 3 for full experimental details.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, G., Xiao, K., Chen, X. et al. Direct deaminative functionalization with N-nitroamines. Nature 648, 341–348 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09791-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09791-5