Main

Until 2019, the largest constellation of artificial satellites was the Iridium system, comprising 75 spacecraft in low Earth orbit (LEO) at altitudes h between approximately 630 km and 780 km. Radio emission in the 1,621–1,628-MHz band from Iridium satellites was one of the first sources of electromagnetic pollution from space to be addressed by the calibration pipelines of ground-based observatories6. Over the past few years, the number of satellites has increased to approximately 15,000. Owing to the reduction in the cost per kilogram of launching payloads to LEO, the number of artificial satellites has grown exponentially since 2020. Over this era, the proposals of telecommunication satellites to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) have increased by two orders of magnitude7. Launches are expected to be even more accessible in the future because the advent of next-generation superheavy launchers (Space Launch System, New Glenn, Starship and Long March 9) will likely reduce launch costs and increase the capability to deploy more satellites to even higher orbits. If all FCC filings result in launches, Earth would be orbited by half a million artificial satellites by the end of the 2030s7.

Early observations of the first Starlink satellites in 2019 revealed that reflected light from the spacecraft was easily visible to the unaided eye, interfering with ground-based observatories at all wavelength ranges8,9,10. As their apparent positions in the sky change, they leave a trace of light in the exposures of astronomical images, called satellite trails. Satellite trails passing over a science target can render the observation totally unusable. Even if the trail misses the object, it can generate a background light gradient (scattered light) and increase the photon noise. For new-generation wide-field ground-based telescopes, such as the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, conservative studies assuming constellations of 26,000–48,000 satellites, significantly fewer than those proposed at present, predict that 20% of the midnight images will present satellite trails and 30–80% of all exposures obtained at the beginning and end of the night will be affected11,12.

LEO satellites are detected through reflected solar light and are therefore mostly visible at twilight after sunset and before sunrise, but they also emit thermal infrared radiation and radio wavelengths. However, most mitigation efforts have been focused on making the satellites optically dim through changes in surface design and attitude so that they are not detectable by the human eye (visible magnitude, mvis ≈ 6–7 mag). The typical apparent magnitude of the first-generation Starlink satellites was mG = 5.1 ± 1.1 Gaia G magnitudes13,14. Dark coatings and optical blocking systems have proven to be inefficient to reduce the presence of satellite trails in astronomical imagery data12, with only a mild decrease in the optical magnitude (from 4.6 mag to 5.9 mag in the case of VisorSat and 6 mag in the case of DarkSat)14,15,16, reducing the visual impact for unaided-eye observers but remaining very bright for astronomical observatories. In fact, newly launched Direct to Cell (DTC) satellites in orbit present much larger solar panels and chassis (125 m2 versus 26 m2) and are much brighter than regular internet satellites (up to mvis ≈ 0–1 mag, compared to the original 4–6 mag), despite their lower orbits and thus faster transits17. Super-bright satellites, such as BlueWalker 3, are comparable to the magnitude of the brightest stars in the sky18.

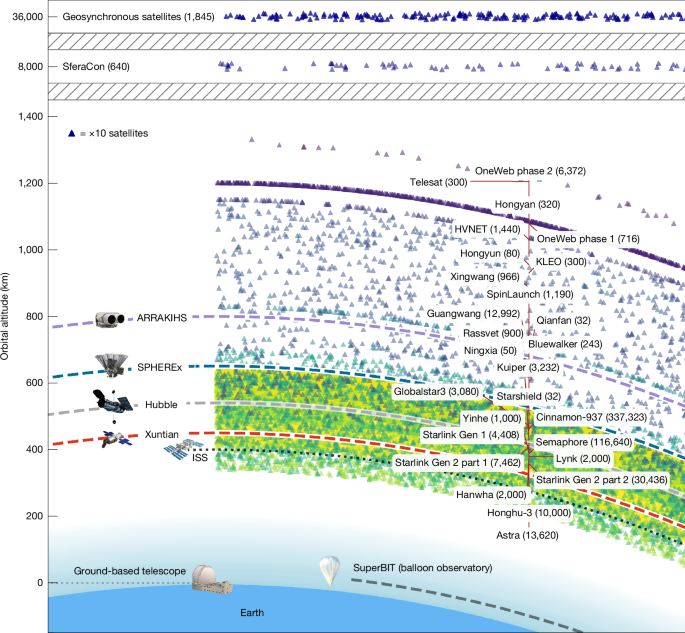

Mitigation strategies have included pausing ground-based telescope operations during the evening and morning twilights, when the satellites with lowest-altitude orbits (h < 600 km) are most visible19. Although using this technique avoids many of the brightest satellite trails with orbit altitudes below h ≈ 600 km, some critical scientific programmes, such as discovery surveys for unknown hazardous Earth orbit-crossing asteroids, can only be conducted through twilight and sunrise observations, exactly when the satellite trails are most common3. Satellites at higher altitudes may pose an even greater challenge because they can be visible for longer periods or even continuously, contaminating images obtained even at midnight8,11. With prospects of hundreds of thousands of satellites already proposed at altitudes between 340 km and 8,000 km (Fig. 1 and Extended Data Table 1), the number of contaminated science exposures will increase rapidly.

Although much attention has been directed at the future of ground-based astronomy1,2,3,4, the impact on space telescopes by a crowded near-Earth space environment has been poorly explored. This study focuses on the prediction of image degradation by satellite trails in present and near-future LEO space telescopes. The observations of active space telescopes are already being contaminated by artificial satellite trails. A recent study5 demonstrated that 4.3% of the images obtained by Hubble Space Telescope between 2018 and 2021 already present artificial satellite trails. Considering that the proposed number of satellites is two orders of magnitude higher than the current count, the fraction of impacted images will increase very soon. Extended Data Table 1 gives a summary of the properties of all planned and present satellite megaconstellations, together with the orbits of several observatories. Most satellite layers are planned between 500 km and 700 km, with extended constellations up to 8,000 km (Fig. 1). As a consequence, LEO observatories and every balloon-borne telescope will be affected by these satellites.

The altitude of satellites is compared to the orbits of the Hubble Space Telescope, the Xuntian Space Telescope (Chinese Space Station Telescope), SPHEREx and the proposed ARRAKIHS mission (Table 1). Constellation labels show the number of proposed satellites. Each symbol represents ten satellites.

To forecast the frequency of satellite trails in LEO space telescopes, this study simulated the observations of four different platforms: (1) Hubble Space Telescope; (2) Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer (SPHEREx)20; (3) Xuntian Space Telescope (also known as Chinese Space Station Telescope, launch planned for 2026)21; and (4) Analysis of Resolved Remnants of Accreted galaxies as a Key Instrument for Halo Surveys (ARRAKIHS) space telescope (European Space Agency (ESA) F-class proposed mission, to be launched no earlier than 2030)22,23. The specifications for each telescope in terms of orbital altitude, inclination, wavelength range, field of view (FOV) and spatial resolution are detailed in Extended Data Table 2. Simultaneously, we simulated a series of constellations following the announced orbital configurations (altitude, number of shells, planes and satellites per plane) to the FCC and ITU up to date (March 2025), with increasing numbers up to one million satellites (twice the number proposed at present), aiming to estimate the number of trails detected by the telescopes per average exposure. The simulated telescope observations accounted for realistic survey plan constraints (Earth avoidance angle, exposure time and maximum zenith angle) and configuration of the telescope (orbit and FOV).

Satellite trail frequency

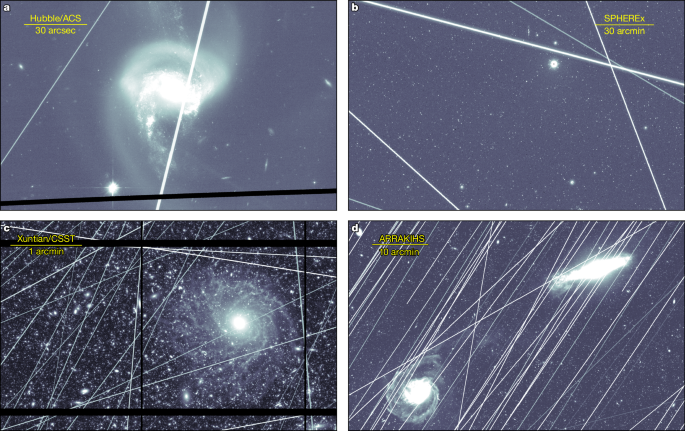

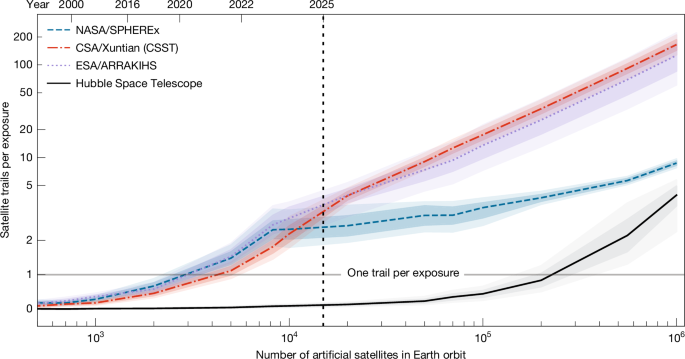

Our simulated images (Fig. 2; see the full FOV in Extended Data Figs. 8–11) underscore the dramatic increase in satellite trail contamination with increasing number of LEO satellites (Fig. 3). Table 1 contains the number of satellite trails per exposure and the fraction of exposures showing at least one trail. If the planned constellations are completed (number of satellites (Nsat) of approximately 560,000), the average number of satellite trails per exposure for each telescope would be \({2.14}_{-0.47}^{+0.46}\) (Hubble Space Telescope), \({5.64}_{-0.27}^{+0.28}\) (SPHEREx), \({69}_{-22}^{+21}\) (ARRAKIHS) and \({92}_{-10}^{+11}\) (Xuntian). More than one-third (39.6 ± 4.6%) of the Hubble Space Telescope images would present at least one trail, whereas this fraction increased to more than 96% for SPHEREx, ARRAKIHS and Xuntian. At a population of one million satellites, the number of satellites detected duplicated, contaminating up to \({4.46}_{-0.57}^{+0.56} \% \) of the FOV in Xuntian and \({22.3}_{-7.2}^{+7.4} \% \) in ARRAKIHS, four times the typical fraction of pixels lost to cosmic rays in Hubble Space Telescope (5%).

a–d, Simulated exposure for Hubble (a), SPHEREx (b), Xuntian (c) and ARRAKIHS (d) space observatories, showing sectors affected by satellite trail contamination. The satellite trails represent the effects of the planned satellites using the orbital and physical parameters of the announced constellations to be operational by 2040 (Fig. 3). Background galaxies were modelled on the basis of previous studies34,35. Full images can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15707680 (ref. 36) and also see Extended Data Figs. 8–11.

The average number of satellite trails visible in each exposure is shown in relation to both the number of artificial satellites orbiting Earth (lower x axis) and epoch (upper x axis). Blue, SPHEREx; red, Xuntian; purple, ARRAKIHS; black, Hubble Space Telescope. Contours represent the 95% confidence levels for the mean number of trails. Horizontal solid line indicates one trail per exposure critical contamination level; vertical dotted line marks the current number of active and inactive satellites in orbit (15,000 as of March 2025).

Relative to ARRAKIHS or Xuntian, the substantially larger FOV of SPHEREx (39.5 deg2 versus 1.2–1.4 deg2) increases the probability of a satellite being detected by the telescope. However, its strict pointing constraints and higher altitude compared to Xuntian (650 km versus 450 km) compensate the risk. In particular, the strict maximum zenith angle requirement (35 deg) excludes the regions of the sky closer to the limb of Earth where a higher number of satellites are visible per square degree (Extended Data Table 2). Xuntian presents the highest number of trails of all the considered telescopes owing to its lower orbit altitude. In the case of ARRAKIHS, despite being in a higher orbit (800 km) and having a relatively smaller FOV than SPHEREx (1.4 deg2), its reduced spatial resolution causes the trails to cover a wider fraction of FOV, and the observing plan requires long exposure times (600 s), potentially reaching orientations closer to the limb of Earth than SPHEREx, thus increasing the probability of a satellite crossing the detector. This result indicates that stricter observational requirements can reduce the number of trails in ARRAKIHS and Xuntian at the expense of a reduced observable time and area per orbit. Note that both telescopes are still in the development phase; therefore, their operational constraints could adapt or change.

We validated the methodology by comparing satellite trail detection in the recent Hubble Space Telescope data to the predictions from simulations on the basis of the satellite population in October 2021 (5,589 satellites with a large cross-section of more than 1 m2). Our simulations predicted that 4.3 ± 1.5% of the recent images should present at least one satellite trail, a value remarkably consistent with the rate of 4.3 ± 0.4% observed in Hubble Advanced Camera for Surveys/Wide Field Channel (WFC) images acquired between 2018 and 2021 (ref. 5). The substantially narrower FOV of Hubble Space Telescope (2 × 2 arcmin) reduced the observed trail frequency to three times lower than that of SPHEREx. Only after the population of artificial satellites has exceeded 200,000 would Hubble display, on average, one satellite trail in every exposure. At population levels of 1,000,000 satellites, Hubble would observe an average of \({3.93}_{-0.92}^{+0.98}\) satellites per exposure (39.7 ± 4.7% of the images would show one trail or more). For comparison, SPHEREx, ARRAKIHS and Xuntian will observe \({8.71}_{-0.44}^{+0.44}\), \({127}_{-41}^{+43}\), and \({165}_{-21}^{+21}\) satellite trails per average exposure, respectively.

Satellite trail brightness

A satellite crossing the FOV of a telescope does not guarantee that the satellite trail will be visible in the imagery data. The surface brightness magnitude of a satellite trail depends on several factors, including the apparent angular velocity (the faster a satellite crosses the detector, the dimmer the trail will be), source of illumination (Sun, Moon or Earthshine), satellite cross-section (larger satellites are brighter), albedo, distance from the observer to the satellite, temperature and attitude of the satellite surfaces with respect to the illumination source and the observer.

Owing to the limited availability of information specifying shape and optical properties for commercial satellites, a precise prediction of the brightness of satellite trails is not possible at present. We discuss potential mitigation measures in the Discussion. However, we can provide order-of-magnitude estimates of the peak surface brightness of the satellite trails on the basis of current observations of satellite megaconstellations and the results from the simulations presented above. The methodology to quantify the satellite trail surface brightness is detailed in ‘Satellite trail brightness’ (Methods).

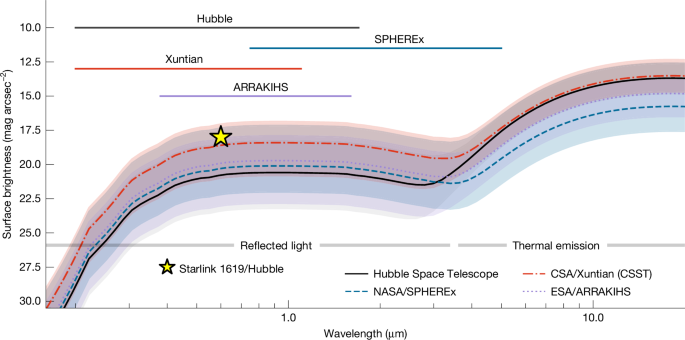

Our simulations (Fig. 4) predicted that the typical surface brightness of detectable satellite trails will range from µ = 18 mag arcsec−2 to µ = 23 mag arcsec−2. Table 1 shows the average surface brightness of satellite trails for satellites illuminated and not illuminated by the Sun. The results show that, on average across all telescopes, the Sun-illuminated trails exhibited µ = 18–19 mag arcsec−2 (except SPHEREx, which recorded \({21.1}_{-3.0}^{+1.9}\) mag arcsec−2), whereas the detected satellite trails illuminated solely by the Moon and Earthshine were four magnitudes dimmer (µ = 22–23 mag arcsec−2). Under typical exposure times, these trails will remain detectable in the images captured by the four space telescopes considered.

The blue dashed line represents SPHEREx, the red dashed–dotted line corresponds to Xuntian, the black solid line indicates the Hubble Space Telescope and the purple dotted line denotes ARRAKIHS. The top horizontal coloured lines represent the spectral range of each observatory. The shaded areas represent 1σ uncertainties. The yellow star indicates the observed surface brightness of a satellite trail in the Hubble Space Telescope, estimated from the WFC3/UVIS F350LP observation of Starlink 1619. Hubble observation principal investigator: S. Porter (Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes programme ID: 16183). Satellite ID by J. McDowell.

As a verification, we measured the surface brightness of the only confirmed Starlink satellite trail observed by Hubble on 2 November 2020 (Starlink 1619; iedk12aoq; WFC3/UVIS F350LP; programme ID: 16183; S. Porter). The satellite trail had an approximate width of 7.9 arcsec (200 pixels) and a surface brightness of µ = 18.0 ± 0.1 mag arcsec−2, compatible with the predicted surface brightness distribution (Fig. 4). Moreover, assuming a maximum cross-section of 26 m2 for Starlink V1 satellites and a random orientation to the observer, we can estimate a distance between Hubble and Starlink 1619 of \({d}_{{\rm{sat}}}={88.9}_{-16.2}^{+7.9}\,{\rm{km}}\) (equation (1)). The surface brightness of the Sun-illuminated simulated satellite trails in Hubble at dsat of approximately 90 km is therefore consistent with the observations of Starlink 1619 (Extended Data Fig. 5), supporting our results.

Discussion

Mitigation is only possible after careful quantification. Our results show that astronomical images from current and new-generation space telescopes will be contaminated by light reflected from telecommunication satellite constellations in LEO. If all the proposed satellite constellations are completed, we forecast that 96% of the exposures of SPHEREx, ARRAKIHS and Xuntian will present at least one Sun-illuminated satellite trail. The average number of satellite trails per typical exposure in would range from \({5.6}_{-0.3}^{+0.3}\) for SPHEREx to more than \({69}_{-22}^{+21}\) in ARRAKIHS. At the lowest orbit altitude, Xuntian Space Telescope will be the most affected, with \({92}_{-10}^{+11}\) satellite trails per average exposure. One-third of the exposures obtained using Hubble Space Telescope will show contamination by satellite trails. The expected surface brightness of the detected satellite trails, as confirmed by Hubble observations, ranges from µ = 18 mag arcsec−2 to µ = 23 mag arcsec−2, placing them orders of magnitude above the detectability limit (Extended Data Table 2).

In the Astro2020 Decadal Survey, the National Academy of Science states that “satellite constellations pose a parallel threat to the radio sky as to ground-based optical telescopes”24. Expanding on this concern, this study demonstrated that the threat is not limited to ground-based telescopes but extends to all LEO space telescopes. Although analytical approximations can be obtained for certain orbits, the actual number of satellite trails may depend on mission-dependent factors, including the survey design, exposure times and characteristics of the orbit of the observatory. In this paper, we present a first-order forecast to the number of satellite trails that cross the FOV of a set of observatories representing a range of orbital scenarios. We focus on the impact for imaging observations. Spectroscopic observations (that is, grism) may be even more severely impacted because they require longer exposure times and satellite trails are more difficult to identify. This study complements similar tools created for ground-based telescopes25,26,27 and provides contamination-level predictions for future and present space missions.

In February 2024, the International Astronomical Union Centre for the Protection of the Dark and Quiet Sky published a consolidated list of recommendations for satellite operators, manufacturers and industry partners to minimize the impact of satellite constellations in astronomy. These recommendations include (1) limiting the reflectivity of satellites; (2) minimizing high-amplitude flares caused by orientation changes; (3) supporting an observing network to characterize light contamination from satellites; and (4) performing bidirectional reflectance distribution function tests on the surfaces of spacecraft and sharing their properties with the astronomical community. In addition, we emphasize the need for enabling (1) prevention, by identifying an optimal upper limit for the orbits of large satellite constellations, above which space telescopes can operate minimizing interference; (2) avoidance, by maintaining an updated and historic open archive of live orbital solutions for each active and derelict spacecraft and potential debris associated with them, as well as equivalent cross-sections and attitude angles28; and (3) correction, by providing higher-precision orbital solutions. Orbital elements must be as precise as possible to enable prediction and avoidance of satellite trails. For reference, for the average Hubble satellite distance in our simulations (dsat = 1,500 km), the orbital solution must be precise up to 3.5 cm to identify the trail with a 0.05 arcsec resolution. By contrast, the precision of the widely used two-line-element orbit propagation format is 1 km (ref. 29).

LEO space telescopes are sensitive to satellites not only above but also below their orbit altitude, depending on the Earth limb avoidance angle (Extended Data Fig. 2). In fact, CHEOPS (h = 700 km) observations have already been affected by satellite trails from satellites located at approximately 540 km (ref. 30). Nevertheless, satellite constellations at lower orbits interfere less with the operations of all types of telescopes because they are shadowed by Earth for a longer period of time, making them up to four magnitudes dimmer (‘Satellite trail brightness’). Limiting the satellite constellations to orbits lower than those of space telescopes is a promising method to prevent interference with astronomy. However, other potential implications of lower-orbit satellite constellations must be considered. For example, continuous reentries of satellites have been observed to increase the amount of aluminium oxide nanoparticles in Earth’s stratosphere, which may potentially deplete the ozone layer as the number of satellite constellations grows31 and could generate global atmospheric temperature anomalies of up to 1.5 °C (ref. 32). Placing large satellite constellations at extremely low orbits would increase atmospheric drag and increase the rate at which the satellites would burn up in reentry. It is therefore critical to designate safe and limited orbit layers for a sustainable use of space.

The brightness, and therefore the detectability, of satellites strongly depends on the relative orientation of the satellites with respect to the observer and the Sun. After launch and before operations, Starlink satellite orientation follows an ‘open-book’ orientation, with major axis of the satellite parallel to the ground to minimize drag during thrusting and orbital rising. This open-book orientation maximizes the observed reflective surface for ground-based observatories, making them brighter (up to 2 mag)13. Upon achieving nominal orbit and as part of the mitigation measures already adopted by the industry, satellites switch to an orientation perpendicular to the ground to minimize solar reflection to ground-based observers. However, this orientation increases the cross-section from the point of view of a LEO space telescope. Owing to the Sun-facing orientation of the solar panels, a space telescope pointing away from the Sun can easily receive the reflected light from the solar panels30. In addition, mitigation plans on the basis of attitude control depend on end-of-life operations. As satellites become non-operational, they may lose attitude control, causing them to tumble and reach angles in which more light reaches the telescopes than originally intended, increasing the complexity of the satellite trails, making their potential correction more challenging or even impossible. Detailed de-orbit plans and enforcement policies are critical.

We are witnessing the beginning of a new era of widespread industrial exploitation of LEO, with an expected 20-fold to 100-fold increase in the number of artificial satellites. Reminiscent of the first reports on the effects of human-emitted chlorofluorocarbons and their depleting effect on the ozone layer in Earth’s stratosphere33, which led to the Montreal Protocol in the 1980s, efforts to quantify the effects of very large satellite constellations are being outpaced by the industry. Our results demonstrate that, contrary to popular belief, space telescopes are not immune to light contamination reflected by artificial satellites. We predict that tens (SPHEREx and ARRAKIHS) to hundreds (Xuntian) of satellite trails will appear in astronomical images captured by LEO space telescopes if the announced satellite constellations become operational. We propose a series of mitigation measures that can be applied to prevent, avoid and correct the unwanted effects of satellite trails in space telescopes, enabling responsible use of LEO for both science and industry.

Methods

Space telescope orbit and attitude simulation

The key objective of this study is the prediction of the number of satellite trails in future and present space telescopes in different configurations, represented by the Hubble Space Telescope (540 km), the terminator-aligned sun-synchronous orbit SPHEREx space telescope (700 km), Xuntian Space Telescope (450 km) and the proposed ESA mission ARRAKIHS (approximately 800 km). The main properties of the four telescopes are summarized in Extended Data Table 2. Xuntian and ARRAKIHS are missions still in development, and their configurations might change before launch. In particular, ARRAKIHS proposed orbit ranges from 650 km to 800 km (ref. 22). Because satellite contamination becomes less frequent at higher orbits, we chose a best-case scenario with an 800-km orbit.

The satellite trail simulation process is schematized in Extended Data Fig. 1. For each observatory, we assumed a survey plan that consisted of a series of pointings (right ascension and declination) taking place at an associated epoch (epoch at exposure start (tstart) and exposure end (tend) with a certain exposure time (texp = tend − tstart)). The available regions on the sky depend on the telescope orbit (as defined by the two-line element) and epoch (that is, a telescope cannot observe a region blocked by Earth), as well as specific survey constraints (Sun avoidance, Earth limb and maximum zenith angles) for each telescope, as summarized below. For Hubble simulations, we randomly selected archival exposures (right ascension, declination, tstart and texp) obtained with the wide-field channel of the Advanced Camera for Surveys during 2023–2024, assuming the closest orbit on time from its recorded history. The typical exposure time was \({t}_{\exp }={540}_{-200}^{+530}\,{\rm{s}}\).

To simulate the survey plan, orbital position and attitude of the SPHEREx, Xuntian and ARRAKIHS space telescopes, we chose random locations in the sky that were accessible with the adopted constraints of each telescope. For SPHEREx, we assumed a maximum zenital angle of 35°, a solar avoidance angle of 91° throughout the exposure and an exposure time of 112.5 s on h = 650 km terminator-aligned Sun-synchronous orbit37. Similarly, we chose h = 800 km terminator-aligned Sun-synchronous orbit for ARRAKIHS, with a fixed exposure time of 600 s (ref. 22) and 7.6° Earth-limb angle (as in Hubble). Finally, Xuntian was assigned the same orbit as the Tiangong Space Station (LEO; h = 450 km; inclination i = 41.47°), a 55° solar avoidance angle, 7.6° Earth-limb angle during the whole exposure and a random exposure time following the same distribution as the Hubble observational record, on the basis of their similar available time-per-orbit, altitude, aperture and spatial resolution.

Satellite constellation orbit

The orbital parameters for the satellite constellations were generated using the Planet4589 public database38, which provides data on the orbital altitude, number of shells, number of orbital planes and satellites per plane for each FCC/ITU-registered satellite constellation. In addition to the simulated satellite constellations on the basis of the orbits described in Extended Data Tables 1 and 3, we included a baseline of 8,544 existing large satellites, including all artificial satellites already orbiting Earth, excluding (1) those classified as part of constellations to avoid duplication; (2) CubeSats; (3) debris; or (4) objects known to be too small to be observed, such as Westford Needles. To analyse the effect of an increasing population of artificial satellite constellations, we randomly selected a varying number of satellites, starting from a baseline population of approximately 100 up to one million satellites. The simulated satellites were randomly selected from the pool described for each simulation, ensuring that we sampled the potential variability across scenarios.

On the basis of the orbital parameters and telescope survey plans, the Cartesian geocentric position \(({\overline{x}}_{t}=(x,{y},{z},{t}))\) of the telescope (observer) during the exposure was calculated (Extended Data Fig. 7). In parallel, the coordinates of the satellite constellation were estimated \(({\overline{x}}_{{\rm{s}}})\). The apparent locations on the sky (right ascension and declination) of Earth, Sun, Moon and the artificial satellite constellation were computed within the local reference frame of the telescope. The locations and extensions of Earth and the Moon were determined using their predicted ephemeris and physical properties, whereas the apparent locations of the artificial satellites were simulated as a function of time by propagating their orbits. Thanks to the described approach, we can determine which satellites are visible (not behind Earth); illuminated by the Sun, Moon or Earth; and/or inside the FOV of each telescope. The code is on the basis of Python/Skyfield39. The final product is a database (satellite trails) of the location of each satellite that crosses the FOV, including its brightness, apparent angular velocity, illumination and phase angles (for the Sun, Moon or Earthshine), distance to the observer and location in the sky as a function of time.

Satellite trail brightness

The surface brightness of satellite trails depends on several factors, including the (1) brightness of the light source; (2) bidirectional reflectance distribution function40 of the satellite and its distance to the observer; and (3) orientation of the reflecting surfaces to the light source41. For order-of-magnitude estimations, we implemented some simplifying assumptions.

A satellite located at a distance dsat (in metres) from a space telescope with a mirror diameter Dmir crossing the FOV leaves a trail with a width θsat (in steradians)27,42:

$${\theta }_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}=\left(\frac{{D}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}+\,{D}_{{\rm{mir}}}^{2}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}\right)+{\sigma }^{2},$$

(1)

where σ represents the optical resolution of the telescope, and Dsat is the equivalent diameter (defined as the diameter of a circle with the same area) of the cross-sectional area of a satellite, assuming a random orientation with respect to the observer. The area of the extended solar panels in new-generation satellites can range from 1 m2 to 125 m2 (ref. 17). In this study, we assumed a uniform distribution between these two extreme values.

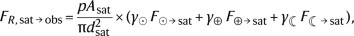

The reflected spectral flux density (FR,sat→obs; in W m−2 Hz−1) of a LEO satellite with cross-sectional area Asat simulated as a Lambertian diffuse sphere can be approximated as a combination of the reflected light from the Sun (F⊙→sat), the Earthshine (F⊕→sat) and the Moonshine (F☾→sat)43 as

(2)

where p is the albedo of the satellite, and γ depends on the satellite illumination phase angle (ϕ) from each source (Sun, Moon and Earth) as

$$\gamma =\frac{2}{3{\rm{\pi }}}(\sin \,\phi +({\rm{\pi }}-\phi )\cos \,\phi ).$$

(3)

In addition, satellites emit thermal black-body radiation (FT,sat→obs):

$${F}_{{\rm{T}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}={\epsilon }\frac{{A}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}B(\lambda ,{T}_{{\rm{sat}}}),$$

(4)

where ϵ = 0.9 is the thermal emissivity44 that reflects a fraction of thermal radiation from Earth (FT,⊕→sat→obs) as well43,45:

$${F}_{{\rm{T}},\oplus \to {\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}={\gamma }_{\oplus }\frac{{\epsilon }p{A}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}}{\left(\frac{{R}_{\oplus }}{{R}_{\oplus }+{h}_{{\rm{sat}}}}\right)}^{2}B(\lambda ,{T}_{\oplus }).$$

(5)

The total optical and infrared emission from a satellite (Fsat; in W m−2 Hz−1) received by an observer would then be:

$${F}_{{\rm{sat}}}=\,{F}_{{\rm{R}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}+{F}_{{\rm{T}},{\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}+\,{F}_{{\rm{T}},\oplus \to {\rm{sat}}\to {\rm{obs}}}.$$

(6)

Because the satellites move across the FOV, their flux is deposited on the detector along the trail. The surface brightness (Σsat; in W m−2 Hz−1 arcsec−2) can be modelled as46:

$${\varSigma }_{{\rm{sat}}}=\frac{{F}_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{A}_{{\rm{trail}}}}\times \frac{{t}_{{\rm{eff}}}}{{t}_{\exp }}$$

(7)

where \({A}_{{\rm{t}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{l}}}={{\rm{\pi }}\theta }_{{\rm{s}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}}^{2}/4\) is the observed angular area of the satellite image, texp is the exposure time (in seconds) and \({t}_{{\rm{eff}}}=\frac{{\theta }_{{\rm{sat}}}}{{\omega }_{{\rm{sat}}}}\) is the effective time that a satellite that moves in the focal plane with an apparent angular velocity ωsat (arcsec s−1) takes to cross its own trail width (θsat). Finally, the surface brightness magnitude of the satellite trail µsat (in mag arcsec−2) will be:

$${\mu }_{\mathrm{sat}}=-2.5{\log }_{10}({\varSigma }_{\mathrm{sat}})-\mathrm{56.1.}$$

(8)

Following a previous study45, we assumed T⊕ = 290 K for the temperature of Earth and a surface temperature Tsat = 280 ± 3 K for satellites. Ground-based measurements estimated that the optical and near-infrared albedoes can vary between 0.1 and 0.5 for LEO satellites47,48, even higher (p ≈ 1) for small pieces of debris. For the purpose of this study, we assumed a uniform distribution for p in the range [0.1–0.5].

The V-band surface brightness magnitude of Sun-illuminated Earth is µV ≈ 2 mag arcsec−2, whereas the magnitude of the full Moon is mV = −12.74. To estimate the Earthshine (F⊕→sat) and Moonshine (F☾→sat), we first scaled the solar spectral energy distribution49 in the V-band to the observer magnitude from Jet Propulsion Laboratory Horizons in the same band. We then integrated their spectral surface brightness by the visible illuminated area (in square degrees) for each satellite’s point of view. For the Moon, the illuminated area is defined by its phase at the epoch of the simulated exposure, whereas for Earthshine, only the areas inside the visible horizon can illuminate the satellite. Extended Data Fig. 6 represents two examples of the resulting contribution of each component to the total observed spectral energy distribution of the satellites.

Extended data

Properties of satellite trails

For space telescopes, exposures with lower-limb angles will present a higher probability to encounter a satellite because they integrate along a thicker layer of LEO. Depending on the altitude of the telescope and the limb avoidance angle, a LEO telescope can observe satellites at lower altitudes than itself30. Extended Data Fig. 2 represents the minimum observable orbit accessible from a LEO telescope as a function of the limb avoidance angle and altitude of the telescope. On the basis of these limits, Hubble can, in principle, detect satellite constellations at h ≈ 350 km or above, which comprises practically the total population of satellites in orbit, planned or already launched (Extended Data Table 1).

Extended Data Fig. 3 represents the distribution of the number of satellite trails detected as a function of the observation distance to Earth’s limb angle. As expected, the number of satellite trails per exposure increased with lower Earth’s limb separation angles. SPHEREx strict zenithal angle configuration prevented most satellite trails from entering its large FOV (Extended Data Table 2). For ARRAKIHS and Xuntian, Earth’s limb separation angles lower than 30–40° result in hundreds to thousands of satellite trails in the simulations with the highest number of satellites (Nsat = 5 × 105−106).

Another important factor is the exposure time. Longer exposure times can lead to an increased number of satellite trails. Extended Data Fig. 4 represents the number of satellite trails detected on each exposure as a function of the exposure time. The results show that, although shorter exposure times present less satellite trails, the dependence with the limb angle is more clear and pronounced. Extended Data Fig. 4 is limited to Hubble and Xuntian because the observing plans for SPHEREx and ARRAKIHS involve fixed exposure times (Extended Data Table 2), designed in combination with their polar Sun-synchronous orbits.

Finally, we explored the dependence of the brightness of the satellite trails as a function of the distance to the satellite and the trail width (Extended Data Fig. 5). We found that the maximum surface brightness tends to occur at distances from the observer similar to 103 km, except SPHEREx, which presented its maximum at 102 km. Satellites at long distances (dsat = 105 km) from Hubble presented high surface brightness as well (µV ≈ 15 mag arcsec−2). Several factors dominate this distribution. The equations in ‘Satellite trail brightness’ (Methods) describe that at large distances from the telescope, satellites are unresolved, and their trail width (θsat) is thus limited by the angular resolution of the telescope. At the same time, satellites at longer distances move relatively slower across FOV, increasing teff. Alternatively, at lower values of dsat, the received flux Fsat increases as \({d}_{{\rm{sat}}}^{2}\), similarly to the angular area of the trail (Atrail) cancelling each other. However, at close distances, the satellites take less time to cross the FOV, effectively decreasing the detected surface brightness in the simulated trails50,51.

Data availability

The properties of the satellite trails used in the simulations analysed in this study are available at Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15707680)36. The Hubble WFC3/UVIS observations analysed in ‘Satellite trail brightness’ (Results) can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.17909/ta6d-ws88.

Code availability

This study used Skyfield39, an open-source software package for computing the positions of stars, planets and satellites in orbit around Earth. All analysis tools were programmed in Python.

References

Dark Sky Oases Working Group, Optical Astronomy Working Group, Bioenvironment Working Group, Satellite Constellation Working Group & Radio Astronomy Working Group. Dark and quiet skies for science and society: report and recommendations. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5898785 (2022).

Walker, C. E. & Benvenuti, P. E. Dark and quiet skies II working group reports. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5874725 (2022).

Walker, C. et al. Impact of Satellite Constellations on Optical Astronomy and Recommendations Toward Mitigations. Techdoc001 (American Astronomical Society and NOIRLab, 2020).

Hall, J. et al. SATCON2: Executive Summary (2021). Report No. 2021i0205 (Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 2021).

Kruk, S. et al. The impact of satellite trails on Hubble Space Telescope observations. Nature 7, 262–268 (2023).

Deshpande, A. A. & Lewis, B. M. Iridium satellite signals: a case study in interference characterization and mitigation for radio astronomy observations. J. Astron. Instrum. 8, 1940009 (2019).

Falle, A., Wright, E., Boley, A. & Byers, M. One million (paper) satellites. Science 382, 150–152 (2023).

McDowell, J. C. The low Earth orbit satellite population and impacts of the SpaceX Starlink constellation. Astrophys. J. Lett. 892, L36 (2020).

Corbett, H. et al. Orbital foregrounds for ultra-short duration transients. Astrophys. J. Lett. 903, L27 (2020).

Grigg, D. et al. Detection of intended and unintended emissions from Starlink satellites in the SKA-low frequency range, at the SKA-low site, with an SKA-low station analogue. Astron. Astrophys. 678, L6 (2023).

Hainaut, O. R. & Williams, A. P. Impact of satellite constellations on astronomical observations with ESO telescopes in the visible and infrared domains. Astron. Astrophys. 636, A121 (2020).

Tyson, J. A. et al. Mitigation of LEO satellite brightness and trail effects on the Rubin Observatory LSST. Astron. J. 160, 226 (2020).

Tregloan-Reed, J. et al. First observations and magnitude measurement of Starlink’s Darksat. Astron. Astrophys. 637, L1 (2020).

Halferty, G., Reddy, V., Campbell, T., Battle, A. & Furfaro, R. Photometric characterization and trajectory accuracy of Starlink satellites: implications for ground-based astronomical surveys. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 516, 1502–1508 (2022).

Tregloan-Reed, J. et al. Optical-to-NIR magnitude measurements of the Starlink LEO Darksat satellite and effectiveness of the darkening treatment. Astron. Astrophys. 647, A54 (2021).

Boley, A. C., Wright, E., Lawler, S., Hickson, P. & Balam, D. Plaskett 1.8 m observations of starlink satellites. Astron. J. 163, 199 (2022).

Mallama, A., Cole, R. E., Harrington, S. & Respler, J. Brightness characterization for Starlink Direct-to-Cell satellites. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.03092 (2024).

Nandakumar, S. et al. The high optical brightness of the BlueWalker 3 satellite. Nature 623, 938–941 (2023).

Williams, A., Hainaut, O., Otarola, A., Tan, G. H. & Rotola, G. Analysing the impact of satellite constellations and ESO’s role in supporting the astronomy community. The Messenger 184, 3–7 (2021).

Feder, R. M. et al. The Universe SPHEREx will see: empirically based Galaxy simulations and redshift predictions. Astrophys. J. 972, 68 (2024).

Gong, Y. et al. Cosmology from the Chinese Space Station Optical Survey (CSS-OS). Astrophys. J. 883, 203 (2019).

Corral van Damme, C., Prod’Homme, T., Isaak, K., Rühl, T. & Sirianni, M. ARRAKIHS: ESA’s new fast-implementation science mission. In Proc. Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2024: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave (eds Coyle, L. E. et al.) 130920Q (Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, 2024).

Guzmán, R. ARRAKIHS: the new ESA F-Class mission to investigate the nature of dark matter. In Presentation at the IHP Dark Energy Workshop (IN2P3/CNRS, 2024).

National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine. Pathways to Discovery in Astronomy and Astrophysics for the 2020s (National Academies Press, 2021).

Lawler, S., Boley, A. & Rein, H. Visibility predictions for near-future satellite megaconstellations. Astron. J. 163, 21 (2021).

Osborn, J., Blacketer, L., Townson, M. J. & Farley, O. J. D. Astrosat: forecasting satellite transits for optical astronomical observations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 509, 1848–1853 (2022).

Bassa, C. G., Hainaut, O. R. & Galadí-Enríquez, D. Analytical simulations of the effect of satellite constellations on optical and near-infrared observations. Astron. Astrophys. 657, A75 (2022).

Hu, J. A., Rawls, M. L., Yoachim, P. & Ivezić, Ž Satellite constellation avoidance with the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time. Astrophys. J. Lett. 941, L15 (2022).

Hartman, P. G. Long-Term SGP4 Performance. Space Control Operations Technical Report No. J3SOM-TN-93-01 (US Space Command, 1993).

Billot, N. et al. In-situ observations of resident space objects with the CHEOPS space telescope. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.18326 (2024).

Ferreira, J. P., Huang, Z., Nomura, K.-i. & Wang, J. Potential ozone depletion from satellite demise during atmospheric reentry in the era of mega-constellations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109280 (2024).

Maloney, C. M., Portmann, R. W., Ross, M. N. & Rosenlof, K. H. Investigating the potential atmospheric accumulation and radiative impact of the coming increase in satellite reentry frequency. JGR Atmos. 130, 2024JD042442 (2025).

Molina, M. J. & Rowland, F. S. Stratospheric sink for chlorofluoromethanes: chlorine atomc-atalysed destruction of ozone. Nature 249, 810–812 (1974).

Drakos, N. E. et al. Deep Realistic Extragalactic Model (DREaM) galaxy catalogs: predictions for a Roman ultra-deep field. Astrophys. J. 926, 194 (2022).

Wetzel, A. R. et al. Reconciling dwarf galaxies with ΛCDM cosmology: simulating a realistic population of satellites around a Milky Way-mass galaxy. Astrophys. J. 827, L23 (2016).

Borlaff, A. S., Marcum, P. & Howell, S. Satellite megaconstellations will threaten space-based astronomy. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15707680 (2025).

Crill, B. P. et al. SPHEREx: NASA’s near-infrared spectrophotometric all-sky survey. In Proc. Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2020: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave (eds Lystrup, M. & Perrin, M. D.) 114430I (Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, 2020).

McDowell, J. General Catalog of Artificial Space Objects (2020); https://planet4589.org/space/gcat.

Rhodes, B. Skyfield: high precision research-grade positions for planets and Earth satellites generator (Astrophysics Source Code Library, 2019); https://ascl.net/1907.024.

Greynolds, A. W., Kahan, M. A. & Levine-West, M. B. General physically-realistic BRDF models for computing stray light from arbitrary isotropic surfaces. In Proc. Optical Modeling and Performance Predictions VII (eds Kahan, M. A. & Levine-West, M. B.) 95770A (Society of Photo-Optical Instrumentation Engineers, 2015).

Fankhauser, F., Tyson, J. A. & Askari, J. Satellite optical brightness. Astron. J. 166, 59 (2023).

Bektešević, D., Vinković, D., Rasmussen, A. & Ivezić, Ž Linear feature detection algorithm for astronomical surveys—II. Defocusing effects on meteor tracks. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 474, 4837–4854 (2018).

Vallerie, E. M. Investigation of Photometric Data Received from an Artificial Satellite. Report No. AD0419069 (Defense Technical Information Center, 1963).

Lebofsky, L. A. et al. A refined “standard” thermal model for asteroids based on observations of 1 Ceres and 2 Pallas. Icarus 68, 239–251 (1986).

Horiuchi, T., Hanayama, H. & Ohishi, M. Simultaneous multicolor observations of Starlink’s Darksat by the Murikabushi Telescope with MITSuME. Astrophys. J. 905, 3 (2020).

Ragazzoni, R. The surface brightness of megaconstellation satellite trails on large telescopes. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 132, 114502 (2020).

Horiuchi, T. et al. Multicolor and multi-spot observations of Starlink’s VisorSat. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 75, 584–606 (2023).

Tyson, J. A., Snyder, A., Polin, D., Rawls, M. L. & Ivezić, Ž. Expected impact of glints from space debris in the LSST. Astrophys. J. Lett. 966, L38 (2024).

Willmer, C. N. A. The absolute magnitude of the Sun in several filters. Astrophys. J. 236, 47 (2018).

Snyder, A. & Tyson, J. A. Satellite streak brightness variation with orbit height. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.06424 (2025).

Kandula, P., Tyson, J. A., Askari, J. & Fankhauser, F. Simulated impact on LSST data of Starlink v1.5 and v2 satellites. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.19092 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This study made use of observations obtained using the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA)/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and made available from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy under NASA contract NAS5-26555. A.S.B. thanks N. Alem for his orbit modelling support. We thank R. Velasco Poblaciones and J. E. Beckman for their careful review of this paper. Support for this study was provided by NASA through Hubble Cycle 30 Award HST-AR-17041, administered by the Space Telescope Science Institute.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Daniele Gasparri, Olivier Hainaut, Meredith Rawls and Jeremy Tregloan-Reed for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Satellite trail simulation methodology flowchart.

Satellite trail simulation methodology flowchart. Left to right: 1) Orbital scene, based on the survey plan, Earth and Moon ephemeris, telescope (observer) and artificial satellite orbits. 2) Estimated sky position of the satellites along the simulated exposure. 3) Filtering satellite trails that cross the field of view, and are illuminated by the Sun, the Moon, or Earth. 4) Final record of satellite trail contamination on each exposure.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Minimum altitude (km) observable from orbit vs. limb avoidance angle.

Minimum observable orbital altitude observable (km) from a Low Earth Orbit space telescope as a function of the Earth’s limb avoidance angle (degrees) and the altitude of the telescope (km).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Number of satellite trails per exposure vs. Earth’s limb angle.

Number of satellite trails per simulated exposure as a function of the distance with the Earth’s limb. Left to right, top to bottom: a) Hubble Space Telescope, b) SPHEREx, c) ARRAKIHS, d) Xuntian Space Telescope. The colorbar represents the number of satellites simulated for each exposure.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Number of satellite trails per exposure vs. exposure time.

Number of satellite trails per simulated exposure as a function of the exposure time. a) Hubble Space Telescope, b) Xuntian Space Telescope. The colorbar represents the number of satellites simulated for each exposure.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Surface brightness magnitude of the satellite trails per exposure vs. distance to the satellite.

Surface brightness magnitude of the satellite trails per simulated exposure as a function of the distance to the detected satellite. Left to right, top to bottom: a) Hubble Space Telescope, b) SPHEREx, c) ARRAKIHS, d) Xuntian Space Telescope. The colorbar represents the width of the satellite trail as detected on each telescope (in arcsec). Surface brigthness magnitudes were measured at the center of the spectral range of each telescope (see Table 2). Upward triangles and circles represent trails generated by satellites illuminated and non-illuminated by the Sun. Yellow star: Observed surface brightness and estimated distance of the satellite trail in Hubble Space Telescope, estimated from the WFC3/UVIS F350LP observation of Starlink 1619.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Examples of the simulated spectral energy distribution of the satellite trails surface brightness.

Examples of the simulated spectral energy distribution of the satellite trails surface brightness (a: spectra of a satellite not illuminated by the Sun, b: equivalent for a Sun-illuminated satellite). Yellow: Sun-reflected light. Grey dotted line: Moonshine reflected light. Blue dotted line: Earthshine reflected light. Dark red dashed line: Thermal satellite emission. Red continuous line: Reflected Earth thermal emission. Grey thick line: Total emission received by observed. See the legend for the properties of the satellite trail.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Distribution of the complete set of proposed constellations (557,794 satellites), projected over the entire globe.

Distribution of the complete set of simulated constellations described in Extended Data Table 1 (557,794 satellites), projected over the entire globe (a, Mercator projection) and over the North Atlantic (b, orthographic projection). Each blue point represents one satellite. Most telecommunication satellite constellations avoid polar orbits, resulting in a reduced number of satellites at very high or very low latitudes.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Example of satellite-contaminated Hubble space telescope exposure simulation.

Example of contaminated Hubble space telescope exposure simulation. The satellite trails were generated by simulating the orbits of N = 560,000 satellites. Exposure properties: Right ascension and declination: (RA = 179.1625, Dec = +55.1656). Limb angle: 31.63 degrees. Exposure time: 1309 s. Background: jbhq01020. PID: 12170.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Example of satellite-contaminated SPHEREx exposure simulation.

Example of contaminated SPHEREx exposure simulation. The satellite trails were generated by simulating the orbits of N = 560,000 satellites. Exposure properties: Right ascension and declination: (RA = 179.2857, Dec = −42.6098). Limb angle: 106.08 degrees. Exposure time: 112.5 s.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Example of satellite-contaminated ARRAKIHS Space Telescope exposure simulation.

Example of contaminated ARRAKIHS Space Telescope exposure simulation. The satellite trails were generated by simulating the orbits of N = 100,000 satellites. Exposure properties: Right ascension and declination: (RA = 249.7058, Dec = −52.0297). Limb angle: 25.94 degrees. Exposure time: 600 s.

Extended Data Fig. 11 Example of satellite-contaminated Xuntian Space Telescope exposure simulation.

Example of contaminated Xuntian Space Telescope exposure simulation. The satellite trails were generated by simulating the orbits of N = 560,000 satellites. Exposure properties: Right ascension and declination: (RA = 274.8913, Dec = +55.8733). Limb angle: 30.70 degrees. Exposure time: 510 s.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borlaff, A.S., Marcum, P.M. & Howell, S.B. Satellite megaconstellations will threaten space-based astronomy. Nature 648, 51–57 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09759-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09759-5