Main

Neutral-atom systems have recently emerged as a leading platform for quantum technologies, enabling advances in quantum simulations1,2, quantum computing4,5,6,7,8,9, atomic clocks and metrology11,12,13, and quantum networking14,15,16. However, an outstanding challenge associated with these systems involves atom loss, originating from errors in entangling operations4, state readout9,24 and finite trap lifetime26. Atom losses necessitate pulsed operation, which limits the performance of these quantum systems, including the circuit depth of quantum computation24,25, the accuracy of atomic clocks23 and the rate of entanglement generation in quantum networking protocols27. For instance, in quantum computing, scaling up to large, practical algorithms requires encoding information in logical qubits, protected by repeated quantum error-correction cycles28,29. Although these cycles can suppress error rates far below those of individual physical qubits28,29, useful quantum circuits may require billions of operations, which eventually lead to loss of atomic qubits that need to be replaced9,24. Similarly, atomic clock applications would benefit from coherent, continuous operation to improve duty cycles and reduce dead time, thereby enhancing stability and precision by mitigating Dick noise, one of the primary limitations of state-of-the-art optical clocks23. Addressing these challenges requires a reliable scheme for fast, continuous reloading of atomic qubits that not only outpaces the rate of errors owing to decoherence and loss but also is consistent with simultaneous coherent qubit storage and manipulation.

Recent experiments have enabled continuous atomic30 and optical clocks31,32,33, as well as the realization of continuous Bose–Einstein condensation34. Although past efforts have primarily focused on controlling atomic ensembles, most recently these techniques have been extended to explore continuous operation with individual atom control17,18,19,20. If expanded to high reloading rates within a coherence-preserving setting21,22, these pioneering experiments highlight the exciting possibility of fully continuous operation of large-scale atomic systems.

Here we introduce a tweezer array architecture that enables such coherent continuous operation at large scale with reloading rates of up to 30,000 qubits per second, nearly 2 orders of magnitude above the current state of the art18,19. Our architecture is based on two serial optical lattice conveyor belts that transport a cloud of laser-cooled 87Rb atoms into the field of view of our microscope objective. From this reservoir cloud, atoms are loaded into optical tweezers ‘in the dark’ (that is, without laser cooling) and then repeatedly extracted into a ‘preparation zone’, where they are laser-cooled, imaged, rearranged and initialized into their qubit states. Once initialized, atomic qubits are then transported and iteratively assembled into a large array in the ‘storage zone’, where dynamical decoupling is applied to maintain qubit coherence. Qubits in the storage zone are spatially protected against scattered cooling light by avoiding direct line of sight to the magneto-optical trap (MOT), and spectrally protected by light-shifting the cooling transition out of resonance (‘shielding’)35. We demonstrate in situ atom replenishment and maintenance of more than 3,000 storage array atoms for more than 2 hours, well beyond the trap lifetime of about 60 seconds. Furthermore, we sustain the storage zone with either spin-polarized qubits (Z basis) or qubits in the equal superposition state (X basis) for, in principle, unlimited duration.

High-rate reloading from a lattice reservoir

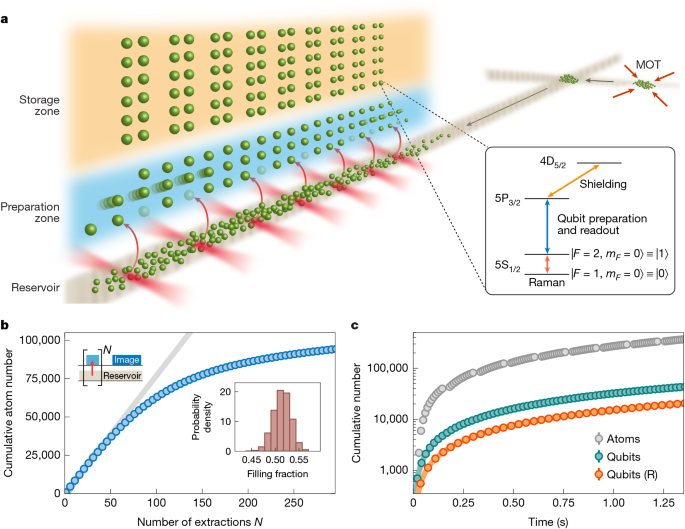

Our dual-lattice architecture is designed for uninterrupted high-rate qubit reloading that enables repetitive usage and periodic replacement of an atomic reservoir (Fig. 1a). The experiment starts by loading around 4 million 87Rb atoms from a MOT into an optical lattice conveyor belt36,37,38,39. Then, the atom cloud is transported through a differential pumping tube to the separate science chamber, where it is transferred to a second lattice conveyor belt and delivered into the microscope field of view to serve as an atomic reservoir (Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2). Using this two-stage procedure, a fresh reservoir of 2.5 million 120-μK cold atoms arrives in the science region every 150 ms. From the lattice reservoir, atoms are repeatedly loaded into a dynamic optical tweezer array of 120 × 12 sites, generated by a pair of crossed acousto-optic deflectors (AODs; Extended Data Fig. 3). To load atoms, we switch on the AOD tweezers overlapped with the lattice reservoir and immediately transport captured atoms into the preparation-zone region placed 220 μm above. This procedure takes less than 2.5 ms and, importantly, allows for multiple extraction cycles from a single reservoir. Following the extraction, atoms in AOD tweezers are transferred to a static tweezer array generated by a spatial light modulator (SLM).

a, A cloud of laser-cooled atoms is transported over 0.5 m from a separate MOT region into the science region via two optical lattice conveyor belts crossed at an angle. In the science region, the optical lattice serves as an atomic reservoir, from which a two-dimensional array of optical tweezers repeatedly extracts atoms into the ‘preparation zone’. Here, atoms are laser-cooled, rearranged into a defect-free array and their qubit state initialized, then transferred into a large-scale storage tweezer array (‘storage zone’). Our dual-lattice scheme avoids direct line of sight between the tweezer arrays and the MOT location, and enables fully concurrent preparation and replenishment of the atomic reservoir. Inset: relevant atomic levels of 87Rb, where F denotes the hyperfine level and mF the magnetic sublevel. During qubit preparation, storage qubits are protected from near-resonant photon scattering with the 5S1/2 → 5P3/2 transition by light-shifting the excited state (‘shielding’). Single-qubit gates are implemented via optical Raman transitions that drive clock states \(| 0\rangle \) and \(| 1\rangle \) (Methods). b, Cumulative number of atoms obtained by N-repeated tweezer extractions from a single lattice reservoir (see top-left schematic), where we observe a decline in tweezer filling fraction after about 70 repeated extractions owing to reservoir depletion (see also Extended Data Fig. 4). For reference, the grey line indicates 50% array filling. Inset: histogram of tweezer filling fractions for the first 30 extractions from the reservoir. Notably, no laser cooling is applied during the tweezer loading process. c, Cumulative number of atoms and qubits obtained by tweezer extraction from repeatedly replaced lattice reservoirs. The grey markers indicate an atom flux of about 300,000 atoms per second after light-assisted collisions, where the brief interruptions originate from the second transport stage of reservoir replacement during which no reservoir is present. Performing the qubit preparation sequence after each extraction, we achieve a continuous qubit flux of 15,000 qubits per second with rearrangement (R; orange) and 30,000 qubits per second without rearrangement (green). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 10 repetitions.

Figure 1b shows the results of repeated tweezer extraction from a single lattice reservoir. Here, we extract atoms for multiple cycles and only image and count single atoms after the final extraction cycle, and quote the cumulative number by summing the atom counts over all N cycles. We find that, initially, array filling fractions of >50% are comparable to conventional tweezer loading from an MOT40, but gradually decline as the reservoir is depleted (see also Extended Data Fig. 4). A key aspect of our dual-lattice design is the ability to extract atoms from one reservoir while preparing and delivering a fresh reservoir to the science chamber. By replacing reservoirs as they are depleted, this approach overcomes capacity limits of any single reservoir. In Fig. 1c, we demonstrate this by repeatedly extracting atoms into the preparation zone as before, now replacing the reservoir every 60 tweezer loading cycles. As a result, we achieve a flux of approximately 300,000 atoms in tweezers per second, corresponding to the maximum rate at which reservoir atoms can be extracted.

Notably, in contrast to the conventional approach to tweezer loading40, no laser cooling is applied during the extraction process. We attribute the ability to load optical tweezers ‘in the dark’ to a combination of stochastic overlap with atoms in the reservoir, and atomic collisions similar to the notion of a dimple trap41 (Methods). Whereas previous experiments17,18,19 have relied on dissipative laser cooling or tweezer-lattice intensity ramps when loading fresh atoms from the reservoir, our scattering-free method helps preserve coherence of nearby storage qubits and avoiding lattice ramp-down enables repetitive usage of the reservoir.

To prepare atomic qubits, we perform an initialization procedure after every extraction from the reservoir (Extended Data Fig. 5). Each step of this procedure relies on two counter-propagating laser beams local to the preparation zone and aligned coaxially with an externally applied static magnetic field24 (Methods). First, an explicit parity-projection pulse via finite-field polarization gradient cooling on a red-detuned F = 2 → F′ = 3 transition prevents multiply occupied optical tweezers. Here, F denotes the hyperfine level of the atomic ground state and F′ the hyperfine level of the 5P3/2 excited state. We continue laser cooling via polarization gradient cooling during AOD-to-SLM handover, then apply a resonant push-out pulse to eliminate atoms in out-of-plane traps10. This is followed by high-contrast, inherently background-free imaging (Methods). Afterwards, we arrange atoms into a defect-free array while further laser cooling via electromagnetically induced transparency with light blue-detuned from the F = 2 → F′ = 2 transition42. Finally, atoms are initialized to the qubit state \(| 0\rangle \) by optical pumping on the F = 1 → F′ = 0 transition, resulting in a state preparation and measurement fidelity of approximately 98% within 20 μs. Under optimal conditions and without atom sorting, the qubit preparation sequence takes 20 ms (Methods).

Figure 1c shows the results of repeatedly extracting atoms and performing the qubit preparation sequence as described above, while the lattice reservoir is replaced in parallel every few tweezer extraction cycles. As a result, we achieve a qubit flux of over 30,000 qubits per second when choosing to not rearrange atoms. With atom sorting, the qubit preparation time approximately doubles and we obtain up to 15,000 qubits per second, rearranged into defect-free batches of 600 qubits. In all cases, the qubit preparation time exceeds the time required for the second transport stage of reservoir replacement; as such, there is always a reservoir present for tweezer extraction and the qubit flux is uninterrupted.

Assembly and maintenance of a large atom array

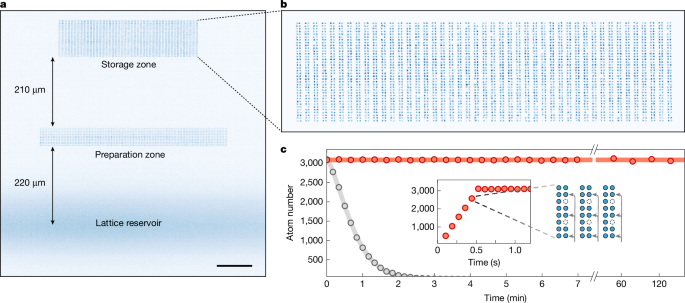

After the preparation sequence, the rearranged array is transported to the storage zone, which consists of 3,240 (90 × 36) SLM-generated optical tweezers with an average trap depth of 270 μK. The storage tweezer array features alternating regularly spaced columns for lossless atom transport in between (Methods), and is positioned with sufficient distance to the preparation zone and the lattice reservoir to limit crosstalk between zones (Fig. 2a).

a, Atom fluorescence image outlining the zone architecture consisting of a lattice reservoir, a 1,440-site preparation zone, and a 3,240-site storage zone. (Averaged) images of each zone are exposed separately and combined with different weights for visualization purposes. Scale bar, 100 μm. b, Single-shot fluorescence image of 3,217 atoms in the 3,240-site storage array (99.3% filling). c, Iterative construction and continuous maintenance of a large-scale atomic array. Initial assembly occurs in 0.5 seconds via 6 loading iterations (inset). Afterwards, one of six segments (‘subarrays’) is ejected from the storage array and refilled with a fresh set of atoms every 80 ms (see also Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Video 1). Here we show cyclic subarray replenishment and continuous maintenance of a 3,000+ atomic array for over 2 hours of operation, far beyond the tweezer-limited lifetime of about 60 seconds (grey). At the final data point, t = 2.3 h, over 50 million individually imaged and rearranged atoms have been cycled through the storage array. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 10 repetitions.

We assemble the storage array in six iterations, each time transferring atoms into one of six segments (‘subarrays’) interspersed throughout the storage array (Extended Data Fig. 6). Preparation and loading of each subarray, including atom transport to the storage zone, takes roughly 80 ms (mostly limited by rearrangement time and image data transfer). Assembly of the entire storage array is completed in about 500 ms with an averaged loading of 3,193 atoms (98.5% filling fraction) over 300 trials. Figure 2b shows a single-shot fluorescence image of 3,217 atoms loaded into the array.

In Fig. 2c, we demonstrate the ability to maintain over 3,000 atoms in the storage array for over 2 hours of continuous operation. After initial storage array assembly, we sequentially eject and refill the longest-stored subarray with a concurrently prepared set of fresh atoms from the preparation zone (Supplementary Video 1). In parallel to atom preparation and subsequent replenishment, we replace the lattice reservoir every other tweezer extraction cycle without affecting the storage-zone array. Using these techniques, we replenish atoms on much faster timescales than their tweezer-limited lifetime, and therefore enable operation that is, in principle, indefinite.

Coherence during continuous operation

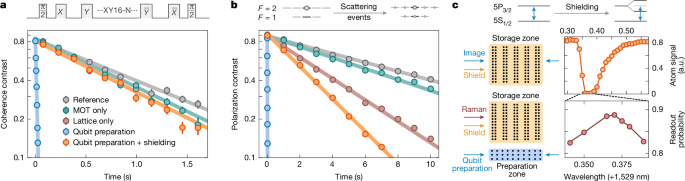

The ability to reload qubits while preserving the coherence of existing qubits is essential for applications in deep-circuit quantum computation and high-bandwidth metrology24,34,43. To address this challenge, in Fig. 3a we first investigate the impact of a simultaneously operating MOT on storage qubit coherence. We observe a coherence time of T2 = 1.15(3) s when applying dynamical decoupling in the presence of the distant MOT, which shows minor modification compared with a reference measurement without the MOT (T2 = 1.34(4) s). In Fig. 3b, we find a similar result when probing the storage qubit depolarization time T1 with and without the MOT. Therefore, by preventing a direct line of sight between MOT and qubits, our angled dual-lattice transport scheme successfully disentangles the scattering-intense initial capture of an atomic gas from parallel quantum operations32,44.

a, Coherence contrast under various conditions when applying N repetitions of an XY16 dynamical decoupling sequence with π-pulse spacing 2τ ≈ 1.6 ms to storage qubits, where the reference measurement yields T2 = 1.34(4) s (grey). Operating the distant MOT in parallel to dynamical decoupling, we observe a minimal effect on coherence (green) compared with the reference, but a strong effect when additionally imaging in the preparation zone (blue). By applying qubit shielding, we restore coherence almost fully (orange, T2 = 1.09(3) s). b, A similar comparison probing depolarization of qubits initialized in \(| 1\rangle \) with the reference measurement T1 = 12.6(1) s (grey), consistent with Raman scattering calculations owing to the tweezer light51. Although operating the MOT simultaneously has a negligible effect on storage qubits (green), additionally imaging in the preparation zone results in rapid qubit depolarization (blue). Similar to before, this can be mitigated by shielding storage qubits from near-resonant light (orange, T1 = 3.43(3) s), mainly limited by off-resonant Raman scattering from the lattice light to which the shielding is ineffective (brown). A similar investigation for \(| 0\rangle \) state depolarization along with all measured T1 and T2 times is presented in Extended Data Fig. 8. For a and b, the difference of qubit populations measured in \(| 0\rangle \) and \(| 1\rangle \) provides the contrast (Methods). c, Shielding light spectroscopy on storage qubits. First, we image the storage array while applying low-power shielding light at variable wavelength to resolve the 4D5/2 resonance by suppression of imaging signal (top). In a fine scan, we optimize for storage qubit coherence under dynamical decoupling while imaging in the preparation zone by maximizing the readout probability in \(| 0\rangle \) (bottom). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 10 repetitions.

In addition to the MOT, the coherence of existing qubits can be affected by scattered light and magnetic-field changes during mid-circuit qubit preparation. To mitigate this, our beam architecture operates under constant finite magnetic field24 and is localized to the preparation zone. However, we initially observe in Fig. 3a that storage qubit coherence is strongly affected by beam crosstalk during the preparation-zone imaging procedure. To suppress this effect, we protect qubits from near-resonant scattering by light-shifting the excited state35 of storage-zone qubits as shown in Fig. 3c (see also Extended Data Fig. 7), and find that the coherence time can be nearly completely restored (T2 = 1.09(3) s). In addition, we probe storage qubit depolarization under the same conditions in Fig. 3b, resulting in a similar conclusion. Here, however, one observes an increased T1 decay compared with a reference measurement despite shielding, which is largely dominated by off-resonant scattering from the lattice reservoir light (Extended Data Fig. 8). This increase does not measurably affect our T2, but can be further mitigated by, for example, greater reservoir distance from the storage array, smaller lattice reservoir waist or larger lattice detuning.

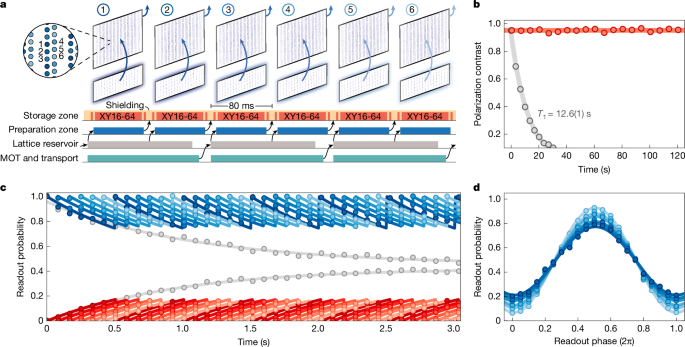

Building on these results, we now assess atom-loss replenishment in simple quantum circuits by repeatedly replacing storage-zone qubits while maintaining coherence. In Fig. 4b, we first show high-rate reloading and continuous maintenance of a large array of spin-polarized storage qubits. Similar to Fig. 2c, we now repeatedly prepare freshly initialized qubit subarrays in the preparation zone, then eject and refill the oldest subarray in the storage zone as shown schematically in Fig. 4a (see also Extended Data Fig. 9). Sequentially replenishing qubits allows us to sustain a high degree of storage array polarization for, in principle, unbounded duration; here, we show maintenance of over 3,000 qubits for 2 minutes.

a, Time sequence visualizing our reloading protocol (see also Extended Data Fig. 9 and Supplementary Video 1). Following the initial storage array assembly, the longest-stored subarray is ejected and refilled with a preloaded set of qubits from the preparation zone every 80 ms, whereas storage-zone shielding is applied throughout. For c and d, storage qubits are placed in the equal superposition state and undergo an XY16-64 decoupling sequence during each reloading cycle. b, Sequentially replenishing storage-zone qubits, we maintain a high degree of storage array polarization (red) for, in principle, unbounded duration. For reference, we provide a T1 measurement without qubit replenishment (grey). c, Similar to b, now additionally applying an Xπ/2 − (XY16-64) − X−π/2 dynamical decoupling sequence during each subarray replenishment. We probe coherence of each subarray at various times during the replenishment cycle by reading out qubits in state \(| 0\rangle \) (blue) or \(| 1\rangle \) (red) as detailed in Methods. Individual subarrays (colour shading) are unaffected by adjacent qubit reloading, and their dephasing is offset in time due to the cyclic subarray reloading protocol. The exponential sawtooth overlays are guides to the eye. For reference, we provide the T2 measurement of a single subarray under the same cyclic decoupling sequence without qubit replenishment (grey). d, After multiple rounds of reloading under dynamical decoupling, we apply a final dynamical decoupling sequence and vary the phase of the last π/2 pulse to read out in different qubit bases. Complementary to c, the observed coherence contrast varies for each subarray (colour shading) owing to the time offset in subarray replenishment. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean across 10 repetitions.

Finally, in Fig. 4c,d, we show the ability to reload and sustain a large array of atomic qubits in a coherent superposition state (see also Extended Data Fig. 10). While shielding and replenishing qubits as in Fig. 4b, we additionally rotate storage qubits into state \(| \,+\,\rangle \) and sustain coherence by applying a dynamical decoupling sequence during each subarray reloading cycle. Shortly before replenishing a qubit subarray with fresh qubits from the preparation zone, we map coherence into population by rotating all storage qubits into state \(| 0\rangle \), eject and replace the oldest qubits with newly spin-polarized ones, then rotate back into state \(| \,+\,\rangle \) as a new reloading cycle starts. This enables us to keep qubits in a superposition state at about 90% duty cycle, with the coherence of individual subarrays unaffected by concurrent reloading cycles.

Discussion and outlook

Our experiments demonstrate an atom-array architecture that enables continuous operation with reloading rates of up to 30,000 initialized qubits per second while preserving coherence across a rearranged large-scale qubit array. The results can be extended along several directions. First, the qubit preparation time can be substantially shortened through optimized readout and the use of field-programmable-gate-array-based and/or artificial-intelligence-optimized rearrangement protocols45,46. Second, larger preparation-zone arrays can be engineered by fully utilizing the system’s optical field of view. We estimate that these technical improvements would lead to a more than fivefold increase in qubit reloading rate, as this rate is directly proportional to qubit preparation time and preparation-zone size. In addition, although the present experiments demonstrate continuous operation for over 2 hours, achieving much longer operation would benefit from active stabilization of the SLM–AOD tweezer overlap or automated beam alignment procedures. Finally, higher-power trapping lasers and high-efficiency diffractive optics, such as metasurfaces47, can be immediately deployed to scale the storage and preparation-zone size, supporting continuous operation of tens of thousands of atomic qubits.

Our results open up a range of scientific opportunities based on atom-array platforms. In particular, our method is directly compatible with a zoned architecture for quantum computation involving Rydberg-mediated entangling gates, local optical Raman control and dynamically reconfigurable qubit arrays9,24. This architecture therefore presents a promising approach towards the implementation of deep, fault-tolerant quantum circuits using error correction. In a complementary experiment conducted in a separate apparatus, we demonstrate the core components of such a fault-tolerant quantum processor, including a method for mid-circuit loss-resolving qubit readout and re-use as well as deep-circuit protocols involving logical qubit teleportation, below-threshold repeated error correction and universal fault-tolerant processing24. Atom losses have a major role in these experiments25, and the ultimate circuit depth is directly limited by atomic reservoir depletion.

Taken together, our experiments open the door for realizing large-scale error-corrected quantum processors. For example, accounting for the current entangling gate fidelity (approximately 99.5%) and atom-loss rate, at a 1-ms duration per gate layer, we estimate that 15,000 rearranged qubits per second should be sufficient to replenish lost atoms in a quantum processor with about 10,000 physical qubits. Furthermore, realistic improvements in entangling gate fidelities to approximately 99.9% and reloading flux to 80,000 qubits per second could enable the operation of several hundred surface code logical qubits with a logical failure rate down to 10−8 (ref. 48). Moreover, the natural compatibility of this architecture with high-rate quantum low-density parity check codes will probably unlock further improvement in quantum processor performance49,50.

Beyond applications in quantum computation, a continuously operating atom-array system could overcome several limitations in quantum metrology23, enabling high-bandwidth and entanglement-enhanced precision quantum sensing12,13. Furthermore, a continuous stream of atomic qubits is essential to achieve fast generation of remote entanglement in quantum networking applications14,15,27. Finally, our high-rate reloading scheme and the transition from pulsed to continuous operation that it enables may be utilized to improve the performance of a broad class of cold-atom experiments, including quantum simulation, sensing and precision measurements.

Methods

Vacuum system

A simplified schematic of our vacuum system is shown in Extended Data Fig. 1a. The system consists of an MOT chamber and a science chamber, separated by a custom-designed differential pumping tube (DPT; Limit Vacuum Technology) with a 1.5-mm back aperture and 4.3-mm front aperture. The DPT maintains a pressure differential between the two chambers and blocks most of the MOT light. Both the DPT and the MOT chamber are tilted by approximately 4° to prevent direct scattering of cooling light onto the atomic array in the science chamber, where the line of sight passes about 1 cm above the array location. The MOT chamber is primarily composed of a glass cell (Precision Glassblowing) with two rubidium dispenser arms (not shown in Extended Data Fig. 1). The science chamber features a double-sided antireflection-coated glass cell (Akatsuki Technology) with optical contact technology. In both chambers, the pressure remains below the measurable threshold of the ion pumps (SAES NEXTorr and Agilent StarCell 75). Several components are omitted from the figure for clarity, including in-vacuum electrodes (not used in this work) and a vacuum viewport, which provides optical access to the in-vacuum mirror.

Objective and imaging system

The experimental set-up features a high-numerical-aperture (high-NA) optical system, which enables high-efficiency imaging and tight trapping of single atoms over a field of view of more than 1.5 mm diameter (Extended Data Fig. 3a). At its core are two 0.65-NA objectives (Special Optics, custom-design). One of the objectives is used for projecting optical tweezers and the other for single-atom imaging. The two objectives maintain diffraction-limited performance across the entire field of view for wavelengths ranging from 780 nm to 860 nm. The objective’s optical transmission is 92%, and we estimate the total absorption to be about 1% (taking into account finite reflection at each antireflection-coated surface), which reduces thermal lensing and enables higher trapping laser power in the future.

For single-atom imaging, we use two 4f telescopes (one high-NA objective and three relay lenses) to map the atomic plane inside the glass cell onto a low-noise camera (Hamamatsu C15550-20UP). The imaging system magnification is 7.6, such that the fluorescence of a single atom is mapped onto approximately 3 × 3 camera pixels. The quantum efficiency of the camera at the 780-nm imaging wavelength is about 50%. All relay lenses used in the objective beam path (both for imaging and tweezer projection) are custom-designed (Special Optics) to accommodate the large field of view.

Tweezer generation

For optical tweezer projection, we use polarizing beamsplitters and dichroic beamsplitters to combine 3 separate beam paths powered by 3 high-power lasers: a 15-W, 828-nm fibre amplifier system (Precilaser) that generates the dynamic optical tweezers for atom transport, and two 15-W, 852-nm fibre amplifier systems (Precilaser) that each form the backbone static tweezer array in the preparation and storage zones (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

The 828-nm dynamic tweezers beam path, dedicated to atom transport and sorting, consists of two perpendicularly mounted AODs (G&H AODF 4085) separated by a 1-to-1 4f telescope. Another 4f system maps the AOD aperture to the Fourier plane of the objective. The AOD-generated tweezers have a waist of about 800 nm and a travel range of 600 μm in each dimension on the atom plane. Depending on the transport pattern required, we dynamically switch between different tweezer configurations within one cycle of the experiment. When extracting atoms from the reservoir to the preparation zone, we use 1,440 tweezers at 4.5-μm spacing with average depth of 450 μK. To transport sorted atoms to or eject atoms from the storage zone, we generate an array of 540 tweezers at 9-μm spacing with an average depth of 600 μK. We empirically find a reduction in tweezer lifetime as we reduce AOD tweezer spacing, potentially owing to atom heating from beating between residual optical potentials of neighbouring tweezers.

Static optical tweezer arrays in the preparation zone and the storage zone are generated in two separate beam paths by two independent SLMs (Hamamatsu X15213-02R) and then combined on a polarizing beamsplitter. Each beam path includes a 4f relay lens system to map the SLM aperture to the Fourier plane of the objective. The SLM phase pattern is calculated using a variation of the weighted Gerchberg–Saxton (WGS) algorithm52, and calculation accelerated with a graphics processing unit. We numerically ‘pad’ the SLM with zeros such that the two-dimensional SLM field array (iteratively optimized using WGS algorithm) is 10 × 10-times larger than the SLM pixel number, enabling 10-times-finer control over tweezer positions53. This corresponds to a tweezer positioning precision of 65 nm, which reflects an order-of-magnitude improvement over the natural diffraction unit of 650 nm.

We find substantial tweezer spacing distortion owing to nonlinear effects across the large array span. To systematically overlap thousands of AOD and SLM tweezers, we run an automated procedure that images both AOD and SLM tweezers on a camera, calculates the displacement between the two sets of tweezers for each site, and feeds back on the target tweezer positions of the WGS algorithm site by site. We also apply Zernike polynomials to correct for aberrations in the optical system54, which increases the tweezer trap depth by about 10% post-correction.

SLM diffraction efficiency decreases as the distance to the zeroth order increases. To homogenize our backbone tweezer arrays in the preparation zone and the storage zone, we apply the following two-step procedure. First, when generating optical tweezer arrays using the WGS algorithm, we precompensate for spatially varying diffraction efficiency by including a ‘sinc’ term in the target array54. This rough homogenization typically yields 15% to 20% inhomogeneity. Then we run an atom-based homogenization procedure that relies on site-resolved measurements of tweezer-induced light shifts, which is used to feed back onto the WGS target intensity at each site. In the preparation zone, we measure the tweezer light shift by probing the F = 2 → F′ = 2 transition; in the storage zone, we infer the differential light shift via Ramsey interferometry between the two qubit states55. After a few rounds of atom-based feedback, we arrive at about 5–6% inhomogeneity in both preparation and storage zone (Extended Data Fig. 3b,c). After aberration correction and homogenization, the average SLM trap depth is 370 μK (270 μK) in the preparation (storage) zone with a tweezer waist of about 800 nm.

MOT and lattice loading

The experiment starts with the preparation of an atom reservoir (Extended Data Fig. 1b). We first load approximately 107 atoms in an MOT within 80 ms and the first optical lattice conveyor belt (Lattice-1) is overlapped throughout. The MOT light is 23-MHz red-detuned from the hyperfine transition F = 2 → F′ = 3, where F refers to hyperfine levels in the 5S1/2 ground state and F′ refers to hyperfine levels in the 5P3/2 excited state. The repumping light, created via modulating a sideband on the cooling light, resonantly drives the F = 1 → F′ = 2 transition. We operate the MOT at a magnetic-field gradient of 13 G cm−1, and use a 395-nm ultraviolet light-emitting diode for light-induced atom desorption from the glass cell. After the MOT stage, the MOT light is ramped to lower intensity and about 140-MHz red-detuning over 7 ms for compression of the atomic cloud into the lattice. A brief idle time follows the lattice loading procedure, in which the cooling lights are switched off and the magnetic field is zeroed. Subsequently, we perform lambda-grey molasses (LGM)56 at low cooling light intensity, with the carrier frequency placed 30-MHz blue-detuned from the F = 2 → F′ = 2 transition and the coherent repumper sideband on 2-photon resonance with the F = 1 → F = 2 transition between both hyperfine ground states. After tLGM = 11 ms, we load approximately 4 × 106 atoms at temperatures T ≈ 20 μK into Lattice-1 as measured via absorption imaging.

Dual-lattice optical transport

We transport atoms from the MOT to the science region using two angled conveyor belt optical lattices32,38,39. Both transport lattices are derived from a single titanium:sapphire laser (Matisse, Spectra-Physics) and approximately 300-GHz red-detuned from the D1 line, which is found to be the empirical optimum for our available laser power (Extended Data Fig. 2d,e). Lattice-1 has a Gaussian beam waist of around 330 μm at the position of the MOT and a minimum waist of around 250 μm. Particularly at the position of the DPT, its beam diameter is roughly three times smaller than the DPT aperture. Both conveyor belt lattices are spatially mode-matched at the handover point, from which the waist of the second conveyor belt lattice (Lattice-2) decreases to a minimum waist of 150 μm in the microscope field of view. Both conveyor belt lattices are created via retro-reflection of their respective incoming beams, which are deflected by two acousto-optical modulators (AOMs) into opposite diffraction orders, then imaged back onto the lattice waist (quad-pass configuration)37. Mounting the AOMs perpendicular to each other ensures a circular beam shape and enables optimal overlap with the incoming lattice beam on retro-reflection. The quad-pass efficiency is (0.88)4 ≈ 60%, such that for typical incoming powers Pin ≈ 1 W we achieve lattice depths Ulat > 500 μK for both conveyor belt lattices across the entire transport distance.

After loading Lattice-1, we linearly ramp the frequency of one of the retro-AOMs to introduce a frequency detuning Δν(t) between both interfering laser beams, and obtain a conveyor belt lattice moving at velocity v = λΔν(t)/2, with λ the wavelength of the lattice laser38,39. The atom cloud is transported over about 39 cm (Extended Data Fig. 2a) before arriving at the handover point after tL1 = 50 ms. Here, we transfer the atomic cloud from Lattice-1 to Lattice-2 within tHO = 1 ms by a simultaneous and opposite linear intensity ramp of both lattice lights and without applying cooling light during the handover (Extended Data Fig. 2b). Finally, within tL2 = 21 ms, Lattice-2 transports the atoms over another approximately 17 cm into the microscope field of view, where it serves as an atom reservoir. For both conveyor belt lattices, we find optimal transport efficiency for accelerations alat ≈ 4,000 m s−2 (Extended Data Fig. 2c) and velocities of 8–10 m s−1, limited by AOM bandwidth. Using this scheme, we deliver reservoirs of approximately 2.5 × 106 atoms at a temperature of around 120 μK into our reloading zone, which corresponds to an approximately 60% dual-lattice transport efficiency at 6 times the original temperature. Most of the observed heating is attributed to the lattice handover, not the long-distance transport.

When periodically replacing the atomic reservoir, we start loading a new MOT directly after the lattice handover and, as such, can deliver a fresh reservoir cloud to the science region every approximately 150 ms. It is noted that only during the second stage of lattice transport, tL2 = 21 ms, no reservoir is available for loading optical tweezers; however, as described in the main text, this is not a limitation to continuous operation as the qubit preparation procedure typically exceeds tL2.

Compared with a single transport lattice design38,39, our dual-lattice architecture offers several advantages. (1) Owing to the angle between both transport lattices and the differential pumping tube aperture, we avoid a direct line of sight and therefore reduce scattering from the MOT onto qubits already present in the science region. (2) The waist of the second conveyor belt lattice becomes largely independent of overall transport distance, and therefore can be decreased within the field of view of the objective. This increases the reservoir density for tweezer loading and also limits the impact of lattice-induced scattering and dipole potentials on other zones. (3) While Lattice-2 is still in active use, atoms in Lattice-1 can be prepared and transported to the handover point in parallel. This enables fast sequential reservoir replacement, and decouples the MOT and lattice loading sequence from science chamber operations.

Tweezer loading from the lattice reservoir

In this work, we load optical tweezers from the dense lattice reservoir without employing additional laser cooling during the loading process. Here we briefly discuss our current understanding of the underlying mechanisms, and outline the effect of loading and extracting tweezers from an active reservoir. In our parameter regime, we expect two mechanisms to contribute to our tweezer loading: stochastic and/or collisional loading. Both critically depend on atomic density n(r, z) in the reservoir, which is a function of atom number N per lattice site, atom temperature T, and both radial and axial trapping frequencies ωr and ωz. Within one lattice site, it is given by

$$n(r,z)={n}_{0}\,\exp \left(-\frac{m}{2{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}({w}_{r}^{2}{r}^{2}+{w}_{z}^{2}{z}^{2})\right)$$

with \({n}_{0}=N{\omega }_{r}^{2}{\omega }_{z}{(m/(2{\rm{\pi }}{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T))}^{3/2}\) the peak density, m the mass of 87Rb, r the radial distance from the centre of the reservoir, z the axial distance from the lattice site, and kB the Boltzmann constant. Neglecting dependencies on atom temperature and the relative trap depth between the lattice and tweezers, we now turn to a brief discussion of both loading mechanisms.

Stochastic loading

When turning on the tweezer, the number of reservoir atoms stochastically overlapped with the tweezer volume can be approximated as Nst ∝ Vtwz⟨n(r = 0)⟩lat, where we assume peak density in the radial direction and ⟨ ⟩lat denotes averaging across the axial lattice sites. These are valid approximations, as the tweezers are far smaller than the radial dimension of the reservoir but capture multiple lattice sites axially. For our reservoir parameters, we estimate an atom density of ⟨n(r = 0)⟩lat ≈ 5 × 1011 cm−3 and tweezer volume Vtwz ≈ 10−17 m3, which results in about 5 atoms stochastically overlapped with the tweezer volume.

Collisional loading

An atom moving through a background gas collides with a rate Γ(r, z) = n(r, z)vrelσ, with vrel the thermal relative velocity between two atoms and σ the scattering cross-section. The two-body collision density is given by \(\gamma (r,z)=\frac{1}{2}n{(r,z)}^{2}{v}_{\mathrm{rel}}\sigma \), such that the collision rate within the tweezer volume is proportional to Γtwz ∝ Vtwz⟨γ(r = 0)⟩lat using the same approximations as above. For our system parameters, we estimate ⟨γ(r = 0)⟩lat ≈ 3 × 1019 m−3 s−1 and therefore loading of about 0.3 atoms per millisecond of tweezer-lattice overlap, assuming 1 atom trapped per atomic collision.

Although these order-of-magnitude estimates imply that stochastic loading is dominating, we point out two simplistic assumptions that this model is making. (1) Although spatial overlap is necessary, it is not a sufficient condition for trapping; additionally considering kinetic energy constraints would lead to a decrease of stochastically captured atoms. (2) Owing to the abruptly altered potential landscape on tweezer turn-on, nearby atoms accelerate towards the trap centre and the atomic collision rate within the tweezer increases; this results in a larger number of atoms loaded via collisions41. For these reasons, we expect both mechanisms to contribute and further investigation is warranted.

In the regime of few tweezer extractions (that is, saturated loading; see also Fig. 1b), we find that, on average, approximately 5 atoms are lost from the reservoir per tweezer extraction, which is of the same order as the combined tweezer loading estimates above. This number is measured by comparing reservoir atom number with the number of atoms obtained in tweezers from repeated extraction, accounting for parity projection. It should be noted that this serves as an upper bound and does not necessarily imply loading of 5 atoms per tweezer, as we expect the rather invasive extraction procedure to accelerate evaporative losses in the reservoir as well. After loading, captured atoms are transported out of the active reservoir perpendicular to the axial lattice potential. As shown in Extended Data Fig. 4b, we observe no difference in survival when moving atoms through the reservoir versus in free space as a function of tweezer velocity19.

Finite-field laser cooling and imaging

A key feature of our reloading architecture is the ability to initialize fresh qubits and perform mid-circuit laser cooling and imaging in the presence of a static magnetic field. Avoiding field changes, such as field-zeroing as typically necessary for polarization gradient cooling (PGC), protects coherence in existing qubits and enables faster qubit preparation cycles. To this end, all qubit preparation and manipulation protocols are designed to operate at a fixed magnetic field of 4.2 G, which defines the qubit quantization axis at all times. The preparation zone is illuminated with a pair of one-dimensional counter-propagating 780-nm beams with opposite circular polarizations (σ+ and σ−) aligned along the magnetic-field axis. The two beams are detuned relative to each other by twice the Zeeman splitting to compensate for the energy shift of hyperfine levels owing to the quantization field57. We use this architecture for laser cooling, imaging, parity projection and qubit state initialization as shown schematically in Extended Data Fig. 5a, with cooling and imaging performing comparably to the zero-field configuration.

To begin qubit preparation on atoms extracted into the preparation zone from the reservoir, an explicit parity-projection pulse is required as our loading mechanism typically results in more than one atom loaded per tweezer. Before ramping up SLM tweezers in the preparation zone, we perform PGC with light 60-MHz red-detuned from F = 2 → F′ = 3 to induce pair-wise atom losses in the AOD tweezers via light-assisted collisions58. After 10 ms, we hand over atoms to the SLM array and observe roughly 50% occupation and less than 1% of sites with more than 1 atom. This parity-projection step therefore sets an upper bound on imaging survival and is crucial for obtaining well-separated imaging histograms. In addition, we observe atoms trapped in weak out-of-plane potentials created by the SLM (Talbot effect), which we remove with a brief resonant push-out pulse10 applied to the entire array during PGC.

Fast, lossless imaging is then used to identify atoms for rearrangement. We image for 10 ms using PGC parameters, which achieves a site-resolved discriminant fidelity of 99.99% (Extended Data Fig. 5b) with a survival probability of 99.5%. Higher imaging fidelity and survival can always be achieved by imaging longer at larger detuning or weaker powers. Our one-dimensional counter-propagating beam configuration offers the added benefit of a background-free imaging signal, eliminating the need for Fourier filtering as the beams do not directly scatter into the imaging objective. During imaging in particular, we observe that atoms from our lattice reservoir occasionally leak into the nearby preparation zone, which are then trapped into tweezers by imaging or cooling light. We avoid this by moving our lattice reservoir roughly a centimetre away from the objective field of view after every tweezer extraction cycle, and move it back before the next cycle. If not accounted for, atom spilling from the lattice and improper parity projection in tweezers can each decrease imaging survival by about 5%, with the exact number dependent on reservoir density and imaging duration.

During the 20 ms to 40 ms of rearrangement, we apply laser cooling via electromagnetically induced transparency (EIT)42. We use the same laser and beam geometry, except in a strong ‘coupling’ and weak ‘probe’ configuration, operating on a 2-photon resonance 70-MHz blue-detuned from the F = 2 → F′ = 2 transition42 with intensity ratio 13:1. We probe the atom temperature via drop-recapture and extract radial temperatures of 12 μK (Extended Data Fig. 5c). A complementary adiabatic trap ramp-down measurement, which is more sensitive to axial temperatures, yields comparable results despite limited momentum projection of the cooling light along the tweezers’ axial direction. All cooling lights (PGC and EIT) contain a repumper frequency addressing the F = 1 → F′ = 2 transition, created by modulating an electro-optic modulator at about 6.8 GHz.

Atom rearrangement

After stochastically loading the preparation-zone 120 × 12 tweezer array, we rearrange the atoms into a defect-free array of typically 540 sites, except for the qubit flux demonstration in Fig. 1c where we arrange to 600 sites. The same two-dimensional AOD pair used for extracting atoms from the lattice reservoir performs rearrangement, controlled by a dedicated arbitrary waveform generator (AWG; Spectrum Instrumentation M4i.6631-x8). Leveraging our unique large-aspect-ratio preparation-zone geometry, we execute efficient row-by-row sorting (Extended Data Fig. 6a). In each row, a single parallel move fills all empty target sites using available atoms while navigating through inter-row gaps to avoid backbone SLM traps. Each row takes 700 μs to sort, with EIT cooling active throughout.

To optimize real-time processing, we precompute all possible move segments as waveform chirps. During each experiment, the rearrangement program selectively synthesizes the precomputed waveform chirps based on the specific atom loading information of that shot (provided by a real-time image analysis program). We exploit the AWG’s FIFO mode to reduce latency from waveform calculation. As each row’s sorting is independent, we stream its waveform as soon as it is computed while moves for the next row are calculated in parallel. This reduces calculation latency by over an order of magnitude. Under optimal conditions, we allocate approximately 20 ms for rearrangement, which takes into account data transfer latency, row-by-row sorting time and a small buffer to accommodate program runtime fluctuations. For all sequences involving storage-zone operation, we increase the camera region of interest (ROI) to include the storage zone, which increases latency (and therefore the time allocated for rearrangement) by about 10–20 ms. This large ROI is unnecessary for future continuously operating experiments (for example, for error-correcting circuits), where imaging is confined to the preparation zone and not required in the storage zone.

For 540-site rearrangement, we achieve an averaged target array filling fraction of 99.6% (Extended Data Fig. 6b), primarily limited by imaging survival. Given our vacuum lifetime of over 150 seconds, losses from background gas collisions contribute less than 0.1% to the rearrangement infidelity. Extended Data Fig. 6a (bottom) showcases a single-shot preparation-zone fluorescence image of a defect-free array after rearranging to 600 sites. Atoms remaining outside the target array are automatically discarded when the subarray is transported to (re)load the storage zone. We intentionally rearrange into every other column of the SLM backbone array, creating a sparse array geometry that reduces the average atom travel distance during sorting, thereby improving both rearrangement fidelity and speed.

Storage array building

One of the key considerations in generating large-scale atom arrays is the trade-off between increasing tweezer spacing to minimize inter-tweezer crosstalk, and decreasing tweezer spacing for higher SLM diffraction efficiency. Therefore, our 3,240-site storage-zone tweezer array features alternating horizontal spacings: wide, 6-μm channels for minimal AOD–SLM tweezer crosstalk during atom transport through the array, and smaller spacings of 3 μm to pack the array close to the SLM zeroth order where diffraction efficiency is substantially higher. The entire array is placed on one side (two quadrants) of the SLM zeroth order, as we empirically find that having large tweezer arrays in all four quadrants introduces additional ghost optical spots between tweezers.

The 90 × 36-site storage array is divided into 6 interleaved subarrays of 45 × 12 sites. Subarrays feature regular tweezer spacings of 9 μm and are filled sequentially, such that the entire storage array is assembled in 6 iterations (Fig. 2c, inset, and Extended Data Fig. 6d). Within each iteration, we first load the preparation-zone array stochastically, then rearrange atoms into a 540-site target array with a spacing of 9 μm horizontally and 4.5 μm vertically. Afterwards, atoms are picked up by AOD tweezers and transported to one of the six subarrays. During this transport, the subarray is vertically expanded from 4.5 μm to match the 9-μm spacing in the storage zone, while the horizontal spacing remains at 9 μm (see also Supplementary Video 1). Maintaining identical horizontal spacings throughout the transport minimizes expansion overhead and enables faster transport. In addition, the sparse subarray structure largely avoids AOD heating at closer spacings.

We observe a slightly lower atom survival probability during tweezer transport to the storage zone when the static lattice reservoir is present, which can be recovered when the lattice potential itself is in motion simultaneously. As described previously, the lattice reservoir is translated by 1 cm out of the objective field of view to avoid lattice spilling during high-contrast imaging, and moved back before the next tweezer extraction cycle. Therefore, we now simply time atom movement to the storage zone to occur synchronously with moving the lattice reservoir back into the objective field of view, thereby mitigating the above effect. Extended Data Fig. 6c showcases storage-zone assembly statistics after 300 repeated trials; on average, we load 3,193 atoms out of 3,240 sites, corresponding to a loading fraction of 98.5%.

Qubit initialization

After rearranging a defect-free array, we initialize the atoms into their qubit subspace. The qubit subspace is spanned by the two hyperfine clock states in the ground-state manifold of 87Rb, which we define as \(| F=1,{m}_{F}=0\rangle \equiv | 0\rangle \) and \(| F=2,{m}_{F}=0\rangle \equiv | 1\rangle \). To prepare the atoms in state \(| 0\rangle \), we leverage the previously discussed one-dimensional local beam configuration. Both of the counter-propagating preparation-zone beams simultaneously address the F = 1 → F′ = 0 and F = 2 → F′ = 2 transitions. By selection rules, state \(| 0\rangle \) is dark to the σ± circularly polarized light field addressing F = 1 → F′ = 0, whereas the states \(| F=1,{m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle \) are optically pumped to \(| 0\rangle \) through \(| {F}^{{\prime} }=0,{m}_{{F}^{{\prime} }}=0\rangle \). Simultaneously, atoms in states F = 2 are depumped into F = 1 by addressing the F = 2 → F′ = 2 transition (Extended Data Fig. 5d). We observe a 1/e time of 5 μs for populating state \(| 0\rangle \). This technique for fast state initialization is advantageous as it requires only a few scattered photons, minimizing heating from scattering, while simultaneously avoiding magnetic-field rotations4. From the preparation-zone Rabi contrast, we infer a state preparation and measurement fidelity of 98.1(3)%, probably limited by polarization impurities and off-resonant scattering to other hyperfine levels in the excited state. The state preparation fidelity can potentially be improved by incorporating Raman-assisted optical pumping schemes4.

Qubit manipulation and readout

We drive the qubit states via optical Raman transitions, in a set-up similar to previous studies59 but operating 400-GHz blue-detuned from the 780-nm transition. The Raman beam drives the qubits at Rabi frequency Ω/2π ≈ 1 MHz. At this intensity, we measure a T1-like scattering lifetime of 10 ms, in agreement with ab initio Raman scattering calculations. From this, we infer a scattering-limited fidelity of 0.99995 per π pulse. We note, however, that this represents an upper bound on our single-qubit gate fidelity; in practice, additional error sources such as atomic decoherence, intensity fluctuations and phase noise may also contribute10. The Raman beam is shaped to homogeneously address qubits in the large storage zone, which is achieved by using a fixed holographic phase plate (HOLO/OR ST-268) that forms a top-hat beam profile across the extent of the array. From measuring row-by-row Rabi frequency, we infer a beam homogeneity of approximately 1.04% root-mean-square variation and 3.4% peak-to-peak variation on the atoms (Extended Data Fig. 7a). To minimize crosstalk between the Raman beam and the atoms in the preparation zone, we knife-edge the beam tail at the intermediate imaging plane of the beam shaping telescope, and thus remove residual light in the preparation zone.

To selectively read out qubits in \(| 0\rangle \), we apply a push-out pulse that resonantly removes atoms in F = 2 from the trap, then image atoms that remain in the F = 1 ground-state manifold. To readout qubits in \(| 1\rangle \), we first apply a π pulse to rotate the population to \(| 0\rangle \), followed by the same push-out and imaging pulse. We follow a slightly different imaging procedure depending on where atomic qubits are read out. In the preparation zone, we use PGC for qubit readout under a finite magnetic field, which, in this work, is primarily used to identify occupied tweezer sites for atom rearrangement, but can also serve as mid-circuit readout in future error-correction protocols. For global readout of all storage array qubits at the end of the experiment, we use a separate retro-reflected circularly polarized global imaging beam at zero magnetic field.

Qubit shielding

Throughout the experiment and particularly during qubit preparation, we protect the 5S1/2 ground-state qubits in the storage zone from near-resonant photon scattering with the 5S1/2 → 5P3/2 transition by addressing the 5P3/2 → 4D5/2 transition near 1,529 nm (ref. 35). This results in an Autler–Townes splitting ±ΔAT ≈ ±2π × 10 GHz of the excited state, and therefore a suppression of scattering from nearby imaging/cooling light with detuning Δcool by a factor of approximately \({({\Delta }_{{\rm{AT}}}/{\Delta }_{{\rm{cool}}})}^{2} > 10,000\) (‘shielding’).

The shielding light is sourced from a single-frequency fibre laser (Connet CoSF-D) outputting up to 10 W at 1,529.6 nm, which is passed through an AOM (G&H 3165-1) for fast switching control and fibre-coupled onto the experimental table. Similar to the Raman beam, we shape the shielding beam with a holographic phase plate (HOLO/OR ST-356) to create a flat-top beam profile of approximately 250 μm along the vertical extent of the storage-zone array with Gaussian beam waist of approximately 50 μm horizontally and 2.5 W projected onto the atoms. The beam tails are knife-edged in an intermediate imaging plane to ensure no shielding crosstalk onto the preparation zone. The knife-edged flat-top beam profile is shown in Extended Data Fig. 7b.

In Fig. 3c, we show the shielding effect in a spectroscopy scan by stepping the 1,529-nm wavelength during simultaneous imaging and low-power shielding of storage-zone atoms, and resolve the 4D5/2 resonance by suppression of global imaging signal. To further optimize shielding performance, we maximize the T2 time of storage qubits as a function of shielding wavelength while locally imaging qubits in the preparation zone. In practice, the shielding light is operated free-running approximately 1 GHz red-detuned from the 5P3/2 → 4D5/2 transition with a measured frequency stability of ±10 MHz.

Maintaining coherence while reloading

In Fig. 3a, we apply N repetitions of a XY16 dynamical decoupling pulse sequence (denoted as XY16-N) with fixed π-pulse spacing 2τ ≈ 1.6 ms. During dynamical decoupling, we measure storage qubit coherence under various conditions. First, we quantify the effect of the distant MOT on storage qubits when pulsing the MOT at a 30% duty cycle with the lattice reservoir lights off. This particular duty cycle is chosen to replicate typical MOT loading cycles in our qubit reloading protocol. Second, we additionally switch on the preparation-zone imaging light while the reservoir is present for the entire probing duration to simulate the effect of concurrent local qubit preparation. We observe no difference between turning on local imaging light with atoms present in the preparation zone versus without, suggesting that the primary source of decoherence during qubit preparation arises from scattered light originating from the optics and apparatus, rather than from photons scattered by atoms in the preparation zone. Lastly, we shield storage-zone qubits while the distant MOT is loaded and held at saturation, the lattice reservoir is present and preparation-zone imaging light is switched on for the entire probing duration. This simulates the most demanding application of storage array shielding. Complementary to Fig. 3a, which measures T2 times under the conditions described above, we similarly probe depolarization of storage-zone qubits when the qubit is initialized in either \(| 0\rangle \) (Extended Data Fig. 8a) or \(| 1\rangle \) (Fig. 3b). Here, in addition to the above variations, we also quantify storage qubit depolarization caused by the lattice reservoir light alone.

Continuous coherent operation

In this section, we detail the experimental sequence used to achieve our results of qubit reloading while maintaining the storage qubit coherence shown in Fig. 4b–d and Extended Data Fig. 10a,b. A sequence schematic is given in Extended Data Fig. 9. First, we transport a lattice reservoir into the science region, from which tweezers repeatedly extract atoms into the preparation zone. Subsequently, loaded lattice reservoirs are transported to the tweezer science region in parallel, such that the reservoir itself is replaced every two tweezer extractions. Once in the preparation zone, atoms undergo the qubit preparation sequence shown in Extended Data Fig. 5a before being transported into the storage zone. The complete qubit preparation sequence, including the move to the storage array, takes a total of about 80 ms and constitutes one reloading cycle. After initial assembly of the storage qubit array, we continue preparing newly state-initialized qubit ensembles in the preparation zone, and eject and refill one of six qubit subarrays in the storage zone as described in the main text. To eject a subarray, the qubits are transferred back into overlapped AOD tweezers and accelerated out of the objective field of view. Storage subarray ejection takes about 5 ms and occurs in parallel to the preparation-zone image used for atom rearrangement. For Fig. 4b, we loop this qubit reloading sequence for variable time before our global imaging readout. Shielding light is applied to the storage zone during the entire experimental sequence.

For Fig. 4c,d, we additionally apply dynamical decoupling sequences (Xπ/2 − XY16-64 − X−π/2) with a fixed π-pulse spacing 2τ ≈ 1.1 ms onto all storage-zone qubits during each reloading cycle. Therefore, within each loop, qubits are first rotated \(| 0\rangle \to | \,+\,\rangle \), then undergo the XY16 decoupling sequence to mitigate dephasing. Right before fresh qubits are moved into the storage array from the preparation zone, we apply a X−π/2 pulse to map remaining coherence to population by rotating back to state \(| 0\rangle \), replace the oldest qubit subarray, then rotate all qubits again to \(| \,+\,\rangle \) as a new reloading cycle starts. This is repeated for a variable number of times, where each subarray is exchanged with a set of fresh qubits every six iterations. In Extended Data Fig. 10a, we supplement Fig. 4c by averaging readout probability over the entire storage array instead of analysing each subarray individually.

Instead of mapping coherence back to \(| 0\rangle \) population after each reloading cycle, we can also map it to alternating \(| 0\rangle \) or \(| 1\rangle \) population by choosing (Xπ/2 − XY16-64 − X+π/2) as the cyclic decoupling sequence. This results in subarrays 1, 3 and 5 hosting qubits in superposition state \(| \,+\,\rangle \) and subarrays 2, 4 and 6 qubits in the opposite state \(| \,-\,\rangle \) during dynamical decoupling after initial array assembly. When mapped back to population, this yields a checkerboard pattern of qubit states \(| 1\rangle \) and \(| 0\rangle \) in the storage array. Analogous to Fig. 4d, this is shown in Extended Data Fig. 10b where the storage array is read out in different qubit bases and each subarray analysed individually.

Control system and timing

We use National Instruments (NI) cards to generate digital and analogue control signals (NI PXIe-6535 and NI PXIe-6738, respectively) for the laser-cooling and trapping stages of our experiment, including the MOT loading, dual-lattice transport and qubit preparation sequences. For operations that require waveform generation with nanosecond precision, we utilize AWGs (Spectrum Instrumentation DN2.663-04 and M4i.6631-x8) whose output is triggered by the NI cards. In our experiments, AWGs handle the timing of single-qubit gates and dynamical decoupling pulses, and supply the chirped waveforms for atom sorting and transport in AOD tweezers.

Our control system is designed to allow for practically unlimited duration of continuous operation. For NI-generated control signals, we calculate and stream the waveform samples on-the-fly to circumvent memory limitations. For AWG-controlled atom transport and dynamical decoupling, we instead store the precalculated waveform in the onboard memory and loop over it for an arbitrary number of times. Here, the dynamical decoupling sequence requires particular care in selecting the signal frequency when looping over the same memory segment to avoid phase jumps in the modulated 6.8-GHz microwave signal. More details of our control software will be discussed in an independent paper that is currently in preparation.

Calibrating and maintaining intensity of light pulses that are too short for active real-time stabilization is a notable technical challenge in continuously operating experiments. For our optical Raman light, we employ a field-programmable-gate-array-based digital servo with digital sample-and-hold60 to stabilize pulse intensity, which eliminates analogue hold decay and integral windup, and enables calibration pulses as short as 5 μs. This calibration pulse is inserted before every XY16-64 decoupling cycle with the 6.8-GHz microwave source detuned by 20 MHz to ensure that qubit states are not driven. Although the calibration pulse flashes onto existing storage qubits, its duration is 3 orders of magnitude shorter than the approximately 10 ms T1-like scattering timescale associated with the Raman light. With the digital hold, we actively stabilize every decoupling cycle in situ, and achieve no long-term decay in pulse intensity and pulse-to-pulse error of ≲1%.

Data analysis

For the measurements in Figs. 3a,b and 4b and Extended Data Fig. 8a, we read out the qubit state after the probing duration and define contrast as \(({P}_{0}(t)-{P}_{1}(t))/({P}_{{\rm{a}}}(t)-{P}_{| {m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle }(t=0))\). Here, P0(t) (P1(t)) denotes the probability to measure qubits in \(| 0\rangle \) (\(| 1\rangle \)) at given time t by reading out the F = 1 hyperfine level without (with) a preceding π pulse as described above. Pa(t) is the probability to measure an atom in any state by omitting the push-out pulse before imaging atoms (lifetime measurement). In addition, we correct for qubits initially populating neighbouring Zeeman states \(| F=1,{m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle \) at t = 0 denoted as \({P}_{| {m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle }(t=0)\), as we observe 5–10% leakage from state \(| 0\rangle \) into other mF states within the F = 1 manifold when transporting qubits from the preparation to the storage array using AOD tweezers. This is attributed to beating of radio frequencies driving the transitions between \(| 0\rangle \to | F=1,{m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle \) levels, which can be mitigated by operating at higher quantization fields or fine-tuning the radio frequencies applied to the AODs in future experiments. To measure \({P}_{| {m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle }(t=0)\), we isolate qubits in states \(| F=1,{m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle \) by first applying a push-out pulse, then a π pulse to transfer the population \(| 0\rangle \to | 1\rangle \), followed by a final push-out pulse before readout. For all measurements of Fig. 3a,b and Extended Data Fig. 8a, we fit an exponential decay to the contrast and quote the fitted 1/e decay time as T2 and T1 times, which are presented in Extended Data Fig. 8b.

For the measurements in Fig. 4c,d and Extended Data Fig. 10a,b, ‘readout probability’ is defined as \(({P}_{0}(t)-{P}_{| {m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle }(t=0))/({P}_{{\rm{a}}}(t)\,-\) \({P}_{| {m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle }(t=0))\), where P0(t) again denotes the probability to measure qubits in \(| 0\rangle \) at given time t as described above, and Pa(t) the lifetime measurement. For the red-shaded lines in Fig. 4c and Extended Data Fig. 10a, we apply a π pulse before the measurement. As before, we measure and correct for qubits initially populating neighbouring Zeeman states \(| F=1,{m}_{F}=\pm 1\rangle \) due to state leakage during atom transport.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Browaeys, A. & Lahaye, T. Many-body physics with individually controlled Rydberg atoms. Nat. Phys. 16, 132–142 (2020).

Gross, C. & Bloch, I. Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Science 357, 995–1001 (2017).

Xu, M. et al. A neutral-atom Hubbard quantum simulator in the cryogenic regime. Nature 642, 909–915 (2025).

Evered, S. J. et al. High-fidelity parallel entangling gates on a neutral-atom quantum computer. Nature 622, 268–272 (2023).

Muniz, J. A. et al. High-fidelity universal gates in the 171Yb ground-state nuclear-spin qubit. PRX Quantum 6, 020334 (2025).

Tsai, R. B.-S., Sun, X., Shaw, A. L., Finkelstein, R. & Endres, M. Benchmarking and fidelity response theory of high-fidelity Rydberg Entangling gates. PRX Quantum 6, 010331 (2025).

Peper, M. et al. Spectroscopy and modeling of 171Yb Rydberg states for high-fidelity two-qubit gates. Phys. Rev. X 15, 011009 (2025).

Radnaev, A. G. et al. Universal neutral-atom quantum computer with individual optical addressing and nondestructive readout. PRX Quantum 6, 030334 (2025).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Logical quantum processor based on reconfigurable atom arrays. Nature 626, 58–65 (2024).

Manetsch, H. J. et al. A tweezer array with 6100 highly coherent atomic qubits. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09641-4 (2025).

Young, A. et al. Half-minute-scale atomic coherence and high relative stability in a tweezer clock. Nature 588, 408–413 (2020).

Finkelstein, R. et al. Universal quantum operations and ancilla-based read-out for tweezer clocks. Nature 634, 321–327 (2024).

Cao, A. et al. Multi-qubit gates and Schrödinger cat states in an optical clock. Nature 634, 315–320 (2024).

Covey, J. P., Weinfurter, H. & Bernien, H. Quantum networks with neutral atom processing nodes. npj Quantum Inf. 9, 90 (2023).

Hartung, L., Seubert, M., Welte, S., Distante, E. & Rempe, G. A quantum-network register assembled with optical tweezers in an optical cavity. Science 385, 179–183 (2024).

Grinkemeyer, B. et al. Error-detected quantum operations with neutral atoms mediated by an optical cavity. Science 387, 1301–1305 (2025).

Pause, L., Preuschoff, T., Schäffner, D., Schlosser, M. & Birkl, G. Reservoir-based deterministic loading of single-atom tweezer arrays. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, L032009 (2023).

Norcia, M. et al. Iterative assembly of 171Yb atom arrays with cavity-enhanced optical lattices. PRX Quantum 5, 030316 (2024).

Gyger, F. et al. Continuous operation of large-scale atom arrays in optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033104 (2024).

Singh, K., Anand, S., Pocklington, A., Kemp, J. T. & Bernien, H. Dual-element, two-dimensional atom array with continuous-mode operation. Phys. Rev. X 12, 011040 (2022).

Muniz, J. A. et al. Repeated ancilla reuse for logical computation on a neutral atom quantum computer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.09936 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Fast, continuous and coherent atom replacement in a neutral atom qubit array. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.15633 (2025).

Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Peik, E. & Schmidt, P. O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 637–701 (2015).

Bluvstein, D. et al. Architectural mechanisms of a universal fault-tolerant quantum computer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.20661 (2025).

Baranes, G. et al. Leveraging atom loss errors in fault tolerant quantum algorithms. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.20558 (2025).

Zhang, Z. et al. High optical access cryogenic system for rydberg atom arrays with a 3000-second trap lifetime. PRX Quantum 6, 020337 (2025).

Pattison, C. A., Baranes, G., Ataides, J. P. B., Lukin, M. D. & Zhou, H. Fast quantum interconnects via constant-rate entanglement distillation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.15936 (2024).

Terhal, B. M. Quantum error correction for quantum memories. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 307–346 (2015).

Preskill, J. Fault-tolerant quantum computation. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9712048 (1997).

Biedermann, G. W. et al. Zero-dead-time operation of interleaved atomic clocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 170802 (2013).

Schioppo, M. et al. Ultrastable optical clock with two cold-atom ensembles. Nat. Photon. 11, 48–52 (2017).

Okaba, S., Takeuchi, R., Tsuji, S. & Katori, H. Continuous generation of an ultracold atomic beam using crossed moving optical lattices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 034006 (2024).

Cline, J. R. K. et al. Continuous collective strong coupling of strontium atoms to a high finesse ring cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 013403 (2025).

Chen, C.-C. et al. Continuous Bose–Einstein condensation. Nature 606, 683–687 (2022).

Hu, B. et al. Site-selective cavity readout and classical error correction of a 5-bit atomic register. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 120801 (2025).

Kuppens, S. J. M., Corwin, K. L., Miller, K. W., Chupp, T. E. & Wieman, C. E. Loading an optical dipole trap. Phys. Rev. A 62, 013406 (2000).

Trisnadi, J., Zhang, M., Weiss, L. & Chin, C. Design and construction of a quantum matter synthesizer. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 93, 083203 (2022).

Klostermann, T. et al. Fast long-distance transport of cold cesium atoms. Phys. Rev. A 105, 043319 (2022).

Matthies, A. J. et al. Long-distance optical-conveyor-belt transport of ultracold 133Cs and 87Rb atoms. Phys. Rev. A 109, 023321 (2024).

Schlosser, N., Reymond, G. & Grangier, P. Collisional blockade in microscopic optical dipole traps. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 023005 (2002).

Comparat, D. et al. Optimized production of large Bose–Einstein condensates. Phys. Rev. A 73, 043410 (2006).

Chow, C. H., Ng, B. L., Prakash, V. & Kurtsiefer, C. Fano resonance in excitation spectroscopy and cooling of an optically trapped single atom. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 023154 (2024).

Savoie, D. et al. Interleaved atom interferometry for high-sensitivity inertial measurements. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau7948 (2018).

Chikkatur, A. P. et al. A continuous source of Bose–Einstein condensed atoms. Science 296, 2193–2195 (2002).

Wang, S. et al. Accelerating the assembly of defect-free atomic arrays with maximum parallelisms. Phys. Rev. Appl. 19, 054032 (2023).

Lin, R. et al. AI-enabled parallel assembly of thousands of defect-free neutral atom arrays. Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 060602 (2025).

Holman, A. et al. Trapping of single atoms in metasurface optical tweezer arrays. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.05321 (2024).

Xu, Q. et al. Constant-overhead fault-tolerant quantum computation with reconfigurable atom arrays. Nat. Phys. 20, 1084–1090 (2024).

Breuckmann, N. P. & Eberhardt, J. N. Quantum low-density parity-check codes. PRX Quantum 2, 040101 (2021).

Bravyi, S. et al. High-threshold and low-overhead fault-tolerant quantum memory. Nature 627, 778–782 (2024).

Moore, I. D. et al. Photon scattering errors during stimulated Raman transitions in trapped-ion qubits. Phys. Rev. A 107, 032413 (2023).

Kim, D. et al. Large-scale uniform optical focus array generation with a phase spatial light modulator. Opt. Lett. 44, 3178–3181 (2019).

Kim, H., Kim, M., Lee, W. & Ahn, J. Gerchberg–Saxton algorithm for fast and efficient atom rearrangement in optical tweezer traps. Opt. Express 27, 2184–2196 (2019).

Ebadi, S. et al. Quantum phases of matter on a 256-atom programmable quantum simulator. Nature 595, 227–232 (2021).

Tomita, T. et al. Atom camera: super-resolution scanning microscope of a light pattern with a single ultracold atom. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.03241 (2024).

Rosi, S. et al. Λ-enhanced grey molasses on the D2 transition of rubidium-87 atoms. Sci. Rep. 8, 1301 (2018).

Walhout, M., Dalibard, J., Rolston, S. L. & Phillips, W. D. σ+–σ− optical molasses in a longitudinal magnetic field. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 9, 1997–2007 (1992).

Pampel, S. K., Marinelli, M., Brown, M. O., D’Incao, J. P. & Regal, C. A. Quantifying light-assisted collisions in optical tweezers across the hyperfine spectrum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 013202 (2025).

Levine, H. et al. Dispersive optical systems for scalable Raman driving of hyperfine qubits. Phys. Rev. A 105, 032618 (2022).

Neuhaus, L. et al. Python Red Pitaya Lockbox (PyRPL): an open source software package for digital feedback control in quantum optics experiments. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 95, 033003 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y. Bao, H. Bernien, S. Cantu, J. Dalibard, S. Ebadi, M. Endres, T. Esslinger, B. Grinkemeyer, N. Jepsen, S. Kolkowitz, J. Léonard, A. Lukin, T. Manovitz, J. Robinson, P. Sales Rodriguez, G. Semeghini, R. Tao, J. Ye, J. Zeiher and H. Zhou for discussions; and S. Geier, J. MacArthur and T.-K. Shen for help with the experiment. We acknowledge financial support from the US Department of Energy (DOE Quantum Systems Accelerator Center, contract number 7568717), IARPA and the Army Research Office, under the Entangled Logical Qubits programme (Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-23-2-0219), DARPA ONISQ programme (grant number W911NF2010021) and MeasQuIT programme (grant number HR0011-24-9-0359), the Center for Ultracold Atoms (an NSF Physics Frontier Center), the National Science Foundation (grant numbers PHY-2012023 and CCF-2313084) and QuEra Computing. M.H.A. acknowledges support by a Rubicon Grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). S.H. acknowledges funding through the Harvard Quantum Initiative Postdoctoral Fellowship in Quantum Science and Engineering. S.J.E. acknowledges support from the National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate (NDSEG) fellowship. D.B. acknowledges support from the Fannie and John Hertz Foundation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.G., V.V. and M.D.L. are co-founders and shareholders, V.V. is Chief Technology Officer, and M.D.L. is Chief Scientist of QuEra Computing. Some of the techniques and methods used in this work are included in provisional and pending patent applications filed by Harvard University (US patent application numbers 63/772,191 and 63/656,377).

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Sylvain de Léséleuc, Takafumi Tomita and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Vacuum chamber and dual-lattice transport sequence.

a, Simplified view of the vacuum chamber. Atoms are cooled and loaded from a MOT into an optical lattice (Lattice-1) and then transported through the differential pumping tube (DPT, orange) to the science chamber. The atomic cloud is then handed over to a second optical lattice (Lattice-2), which is reflected out of the chamber by an in-vacuum mirror. While most MOT light is blocked by the DPT, the tilted design between both chambers avoids direct line of sight between the computational array and the MOT location. b, Summary of the dual-lattice transport sequence, including the MOT stage, loading and cooling of Lattice-1 as well as lattice transport and handover. After the lattice handover, we restart the lattice loading procedure in the MOT chamber, while atoms in Lattice-2 are shipped to the science region where they serve as an atomic reservoir for tweezer extraction. In the Lattice-2 velocity graph, the brief back-and-forth movement used to avoid atom spilling during qubit preparation is omitted for clarity. The grey-shaded regions indicate the previous/next lattice loading cycle.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dual-lattice conveyor belt transport.