- Article

- Open access

- Published:

Nature volume 642, pages 376–380 (2025)Cite this article

-

56k Accesses

-

3 Citations

-

1682 Altmetric

Subjects

This article has been updated

Abstract

The isotopic composition of lavas associated with mantle plumes has previously been interpreted in the light of core–mantle interaction, suggesting that mantle plumes may transport core material to Earth’s surface1,2,3,4,5. However, a definitive fingerprint of Earth’s core in the mantle remains unconfirmed. Precious metals, such as ruthenium (Ru), are highly concentrated in the metallic core but extremely depleted in the silicate mantle. Recently discovered mass-independent Ru isotope variations (ε100Ru) in ancient rocks show that the Ru isotope composition of accreted material changed during later stages of Earth’s growth6, indicating that the core and mantle must have different Ru isotope compositions. This illustrates the potential of Ru isotopes as a new tracer for core–mantle interaction. Here we report Ru isotope anomalies for ocean island basalts. Basalts from Hawaii have higher ε100Ru than the ambient mantle. Combined with unradiogenic tungsten (W) isotope ratios, this is diagnostic of a core contribution to their mantle sources. The combined Ru and W isotope systematics of Hawaiian basalts are best explained by simple core entrainment but addition of core-derived oxide minerals at the core–mantle boundary is a possibility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Ocean island basalts (OIB) form by decompression melting of rising, hot mantle plumes. Some deep-rooted mantle plumes possibly originate from the core–mantle boundary (CMB) and are often marked by the striking occurrence of negative μ182W (parts-per-million (ppm) deviation of 182W/184W from terrestrial standards)1,2,5. Variations in μ182W could only have been established through the decay of the extinct radionuclide 182Hf (t1/2 = 8.9 million years7) following chemical fractionation of Hf and W within the first 60 million years (Myr) of Solar System history (that is, more than 4.5 billion years ago). Some OIB with negative μ182W have high 3He/4He ratios8, characteristics that could be explained by incorporating material from an isolated, undegassed reservoir formed during the lifetime of 182Hf (ref. 5). The core formed with low Hf/W ratios, thus retaining a low μ182W value throughout Earth’s history1,2. Together with the high solubility of noble gases in the core during its formation, this would support a core origin of low μ182W and high 3He/4He in OIB2,3,9,10. Yet, alternative models have been proposed that conform with the chemical and isotopic variations observed in OIB, including the incorporation of material from stranded, late-accreted meteorites in the lower mantle8,11 or from different, early-formed silicate reservoirs5,12,13.

Highly siderophile element (HSE) concentrations in the mantle are most susceptible to core–mantle interaction because the contrast in HSE concentrations between the core and mantle is several orders of magnitude. A collateral effect of core entrainment at the CMB would be the strong enrichment of HSE and the potential influence on HSE isotope systematics on the lower mantle (for example, 186Os/188Os and 187Os/188Os). However, no such effects on HSE systematics can be clearly identified in OIB associated with negative μ182W (refs. 14,15), To reconcile these discrepancies, recent revisions on the core–mantle interaction hypothesis invoke models that could decouple W and He from HSE systematics. The latter require element diffusion across the CMB10,16,17, isotopic equilibration between the outer core and the lower mantle1,18 or the exsolution of minerals from the outer core2,3.

Nucleosynthetic isotope variations of the HSE ruthenium provide a more direct and thus much more powerful tool to investigate the nature of core–mantle interaction. Ruthenium was almost entirely removed from the mantle into the core during Earth’s main accretion19. Its budget in the mantle was later replenished through the addition of chondritic material during a late accretionary phase after core formation had ceased6,20. Differences in the Ru isotopic composition of modern and ancient mantle-derived rocks suggest that the late-accreted material was compositionally distinct from Earth’s main building blocks6. This isotopic disparity is based on the variable contribution of Ru nuclides produced by slow neutron capture (s-process) in different meteorite groups. As the late accretion of meteoritic material does not affect the core, the core should share the s-process-enriched nature of Earth’s earlier, main building blocks. As such we expect mantle sources that record core–mantle interaction to be enriched in s-process Ru nuclides.

Here we determined the Ru isotopic composition of a set of oceanic basalts and picrites from Hawaii and continental picrites from Baffin Island, which have been characterized for their W and He isotope composition in previous studies1,5,8,21,22. In addition, we provide new W and Ru isotope data from basalts from Kauai and Kama’ehuakanaloa (Loihi) and basalts associated with the Galápagos and La Réunion hotspots. To better constrain the composition of the upper mantle we included a set of Phanerozoic peridotites (Eifel) and continental picrites (Rhenish massif). We provide additional data for an Eoarchean dunite from Isua (Greenland) and ores from the Bushveld Complex, that have been previously constrained for their Ru isotopic compositions6,13, to independently verify our analytical setup. We mainly focus on the 100Ru/101Ru and 102Ru/101Ru ratios to constrain Ru s-process variations. These ratios have the largest isotope variability and the highest measurement precision and are therefore the most diagnostic tool for detecting a core contribution in OIB. The variations are reported as ε100Ru and ε102Ru, whereby ε denotes the 0.01% deviation from a laboratory standard.

Ru isotopic compositions of OIB

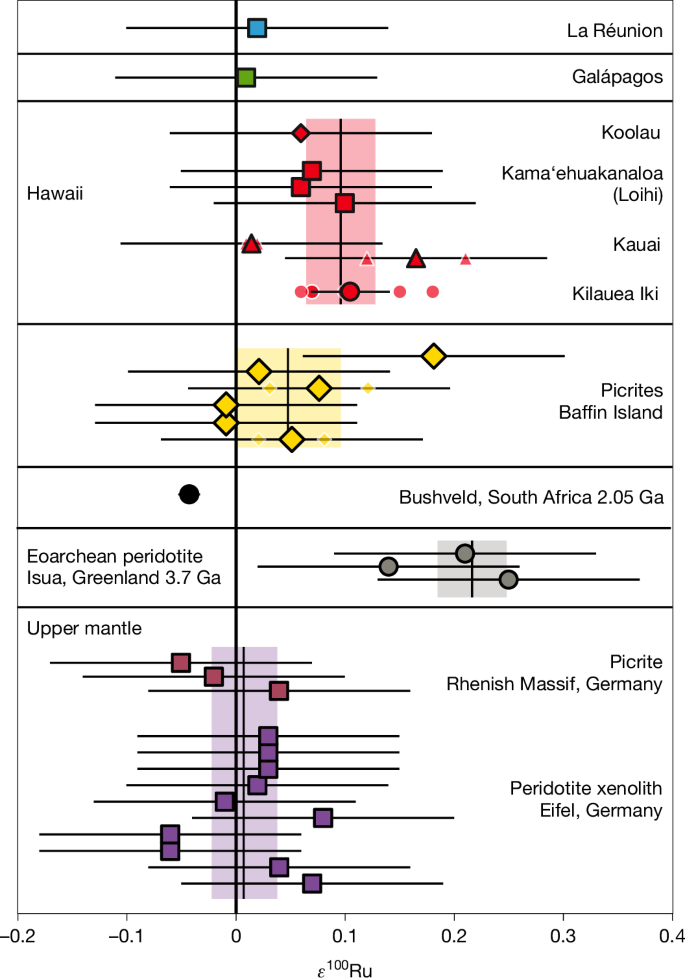

The Ru isotope composition of samples and reference materials are provided in Fig. 1, Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1, together with μ182W data. Eifel peridotites and Rhenish picrites measured in this study have averaged ε100Ru values of 0.02 ± 0.03 and −0.01 ± 0.13 as well as ε102Ru values of −0.04 ± 0.06 and 0.04 ± 0.18, respectively (details on the estimation of uncertainties are provided in the caption of Fig. 1). Their isotopic compositions are in excellent agreement with values previously published for the modern mantle (ε100Ru = 0.00 ± 0.02 and ε102Ru = 0.00 ± 0.02, ref. 6; ε100Ru = 0.01 ± 0.07 and ε102Ru = 0.01 ± 0.42, ref. 23). On the other hand, the averaged composition of Hawaiian picrites and basalts shows a resolvable Ru isotope anomaly with ε100Ru of 0.09 ± 0.03. Although ε102Ru values of 0.07 ± 0.04 are not fully resolved from the upper mantle values, combined 100Ru and 102Ru systematics are in excellent agreement with those expected for nucleosynthetic isotope anomalies, indicating that the Hawaiian plume source is enriched in s-process Ru (Extended Data Fig. 1). Furthermore, two samples from the Kilauea Iki lava lake (ε100Ru = 0.11 ± 0.04) and the Napali Member on Kauai (ε100Ru = 0.17 ± 0.13) show excesses in s-process Ru for individual samples. The Hawaiian mafic rocks therefore provide evidence for the presence of s-process-enriched components in the modern mantle. The averaged Ru isotopic composition for high 3He/4He picrites from Baffin Island shows no resolvable deviations from the upper mantle, with an ε100Ru value of 0.05 ± 0.05 and ε102Ru of 0.04 ± 0.04. One individual sample has an elevated ε100Ru value of 0.18 ± 0.13, indicating a minor excess in s-process Ru within the Baffin Island mantle source. The Ru isotopic compositions of two more samples, associated with the La Réunion and Galápagos Plumes, are not resolvable from the modern upper mantle (ε100Ru = 0.02 ± 0.13 and 0.01 ± 0.13, respectively). Ru isotope data for an Eoarchean dunite from Isua show a ε100Ru = 0.20 ± 0.13 (n = 3), in excellent agreement with data previously reported for the same locality (ε100Ru = 0.22 ± 0.04, n = 14)6,13.

The uncertainties of individual measurements (n < 3) were estimated by the 2σ of repeated analysis of Bushveld pyroxenite OREAS 684 (ε100Ru = −0.04 ± 0.13, 2σ n = 72, Methods). The error bars represent the external reproducibility 2σ. For samples analysed repeatedly (n ≥ 4) error bars show the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of replicate analyses. Small symbols with white outlines represent individual measurements for samples that have been analysed repeatedly. ε100Ru of the modern upper mantle is indicated by the light purple area and defined by the 95% CI of combined data for modern, non-plume-related picrites and peridotites. The light grey area indicates the composition of the Eoarchean mantle6. Light yellow and red areas represent the 95% CI of combined Baffin Island and Hawaii data, respectively. Ga, billion years ago.

The Ru isotopic composition of the core

For reasons outlined earlier, a contribution of Ru from the core is an attractive means of generating the ε100Ru anomalies reported in our OIB. To investigate the viability of this process in more detail it is first important to constrain the ε100Ru of the core. The Ru isotopic composition of Earth’s mantle very dominantly reflects the late-accreted material, added after core formation had ceased6,20,24. By contrast, the composition of bulk Earth, and thus its core, integrates Ru added throughout its history of accretion. As such, mantle and core will have different Ru isotopic compositions, if the material added through late accretion differs from that, added during main accretion.

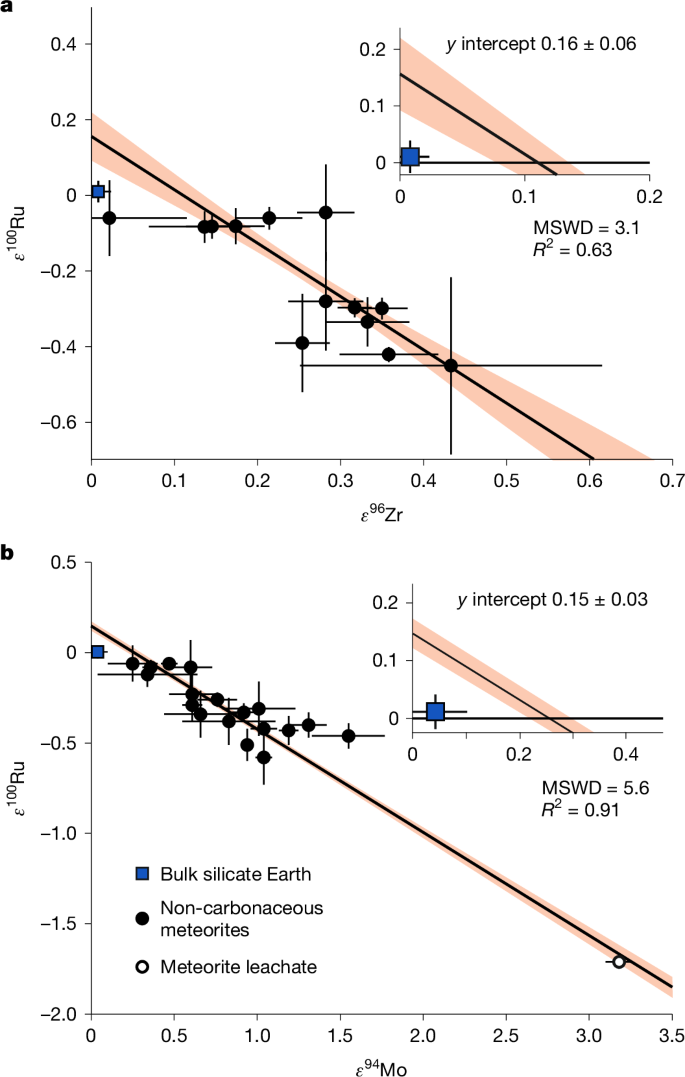

An estimate of the Earth’s bulk ε100Ru (and hence that of the core) can be obtained from meteoritic arrays of isotope ratios of other elements influenced by the same nucleosynthetic processes. Similar to Ru, isotopes of Zr and Mo show s-process variability and non-carbonaceous chondrites show clear correlations between the s-process influenced isotope ratios of ε96Zr, ε94Mo and ε100Ru (Fig. 2)25,26,27. As a non-carbonaceous body, bulk Earth is expected to lie on these arrays25,26,27. The Mo and Zr isotope ratios of the silicate Earth sample different phases of accretion compared to Ru. The mantle composition of the moderately siderophile Mo represents the last 10–15% of main accretion, whereas the mantle composition of the lithophile element Zr averages the entire inventory of accretion24. Thus the ε100Ru predicted by the non-carbonaceous meteorite correlation at bulk Earth ε96Zr (ε96Zr ≈ 0) should represent the value for the Earth’s core (Fig. 2a). Yet, Earth’s modern silicate mantle plots below this correlation (inset in Fig. 2a), implying that material added during the late accretion lowered its ε100Ru. Similarly, the ε100Ru–ε94Mo composition of Earth’s mantle plots below the correlation defined by non-carbonaceous meteorites (Fig. 2b). Combined, both isotope systems show the predicted bulk Earth, and therefore the core, should have an excess in s-process Ru (ε100Ru ≈ 0.15, Fig. 2) relative to the modern mantle. This makes the core a suitable mixing component to account for the elevated ε100Ru of Hawaiian OIB.

a, ε96Zr and ε100Ru data originally reported in ref. 26. b, ε94Mo and ε100Ru data originally reported in ref. 43. The linear regressions, error envelopes and mean square weighted deviations (MSWD) were calculated using the York method in IsoplotR44 based on the meteorite data. The error bars show the 2σ measurement uncertainty for ε94Mo and 95% CI for ε96Zr and ε100Ru. The ε100Ru value and error for the bulk silicate Earth are based on the Eifel peridotite and Hessian picrite data from this study. The inset plots show that bulk silicate Earth does not plot on the non-carbonaceous chondrite correlation defined by either isotope pair.

The nature of core–mantle interaction

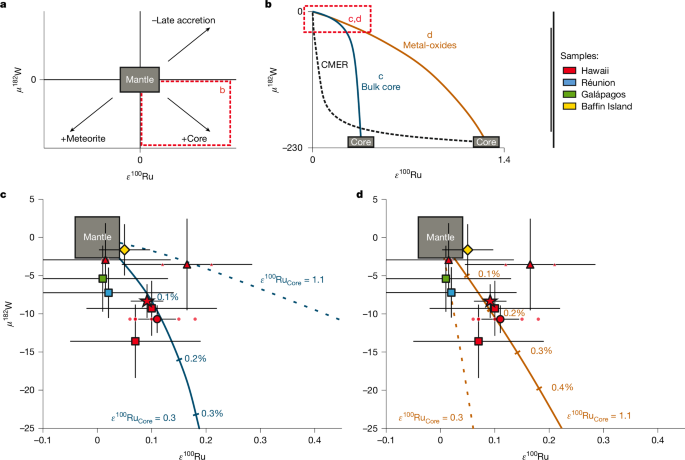

We evaluate a variety of core–mantle interaction models to account for the combined ε100Ru–μ182W OIB data (Fig. 3). In the most straightforward model, bulk core is added to a lower mantle source. Concentrations of Ru and W, as well as the μ182W of the core are well-constrained28,29. We can independently estimate the ε100Ru composition of the core by fitting a core–mantle mixing curve through the OIB data (Fig. 3b,c). The addition of a bulk core component with ε100Ru = 0.25–0.35 best describes the W and Ru isotope variability in the OIB data. Despite the simplified nature of this model, the ε100Ru of the core predicted by the OIB data only slightly exceeds the value derived from the ε100Ru–ε96Zr correlation described in the previous section (ε100Ru = 0.16 ± 0.06, Fig. 2a). To reconcile the global W isotope variability for OIB (μ182W = 0 to −20), less than 0.25% of a bulk core component is required. This would result in OIB sources with the lowest μ182W having a 2.5-fold higher HSE concentrations than those with μ182W = 0 (Extended Data Table 2). At face value, this may be incompatible with the absence of increased HSE concentrations in OIB with negative ε182W (ref. 1). However, modelling the behaviour of HSE in magmatic systems is very complex. Minor sulfide and alloy phases have a lot of control over partitioning but are poorly constrained and potentially variable between different settings30,31,32. As such, their magmatic behaviour may obscure the effects of core–mantle interaction on HSE concentrations of the mantle source. We favour this simple core–mantle mixing model, but recognizing the potential problem with HSE abundances and also explore an alternative.

a, Schematic of the effects of core addition, meteorite addition or subtraction of late-accreted material6 on the composition of the mantle. b, Overview of different core–mantle interaction models. The black dashed line indicates a mixing trend between a CMER and the ambient mantle. Alternative scenarios for the addition of ‘bulk core’ and ‘metal oxides’ are shown in detail in c and d, respectively. c, Binary mixing between bulk core and the mantle. The ε100Ru composition of the core was chosen to fit Hawaiian OIB data. d, Binary mixing between metal oxide-rich outer core layer and the mantle. The composition of the core was calculated by subtracting a late accretion component from the mantle and assuming that the core has a higher ε100Ru than the PLAM (main text). Less than 0.3% of this oxide-rich core component is required to explain W and Ru isotope variability in OIB. Note that if the ε100Ru of the core is 0.3, admixing of an oxide-rich core component cannot reproduce the measured data (dashed line) The μ182W value for Baffin Island is based on the average of data provided in refs. 17,45. Error bars show the external reproducibility as 2σ for μ182W. Error bars for ε100Ru are defined in Fig. 1. The composition of the mantle is defined by the 95% CI of measured reference materials. The star symbol represents the average Hawaiian OIB. For more detailed information on other sample symbols, see Fig. 1.

To reduce the impact on the HSE concentrations of a plume mantle source, core–mantle interaction must then entail a process that lowers the HSE abundances in the component incorporated into the mantle. A viable model invokes the formation of an oxygen-rich outer core domain and subsequent crystallization of metal-rich oxides through secular core cooling2,33. Experimental data indicate that W is enriched in FeO-rich regions of quenched metal alloys whereas HSE are generally depleted2. Data for element partitioning between oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor metallic liquids confirm that W prefers oxygen-rich metal alloys whereas the HSE show oxygen-avoiding behaviour34. We use this partitioning data to approximate the composition of a metal oxide layer on the outer core to have Ru/W = 1.2.

By reducing the Ru/W of the core component, we consequently need to increase its ε100Ru to generate a core–mantle mixing array that passes through our data (Fig. 3b,d). In this context, we note that the existence of terrestrial building blocks with ε100Ru > 0 is required by the occurrence of positive ε100Ru values in Eoarchean rocks from Greenland (ε100Ru = 0.22 ± 0.04)6. The elevated ε100Ru in these rocks is thought to represent a mantle domain that has not fully incorporated late-accreted material. By subtraction of a chondritic late veneer from the mantle source of these Greenland samples, Fischer-Gödde et al.6 calculated the ε100Ru of a prelate accretion mantle (PLAM). This estimate strongly depends on the composition of the late veneer, resulting in a large range of PLAM compositions with elevated ε100Ru = 0.31–3.55 (ref. 6). If we assume that the s-process excess of accreting material was constant throughout main accretion, the Ru isotopic composition of the PLAM approximates that of the core. From this perspective, we explore metal oxide-mantle mixing calculations using ε100Ru = 1.1 for the core as an illustrative and sufficiently high, intermediate value within the range of estimates for PLAM6.

As shown in Fig. 3d, the addition of 0.3% of such an oxide-rich outer core layer to the mantle can reproduce the combined Ru and W isotope systematics in OIB. In contrast to the simple core–mantle mixing model above, this process would increase the HSE concentration of the OIB mantle source by only 3–40%. (Extended Data Table 2), which would be difficult to detect in the composition of its erupted melts. We note, however, that a core ε100Ru = 1.1 is much higher than predicted by the extrapolations of the meteoritic ε100Ru–ε94Mo and ε100Ru–ε96Zr arrays (Fig. 2), which we argue is probably a stronger constraint than the absence of clear HSE concentration anomalies in the OIB samples with elevated ε100Ru. Similarly, a core–mantle equilibrated reservoir (CMER1), previously proposed to reconcile the lack of HSE enrichment in OIB with a putative core contribution, cannot reconcile the presence of elevated ε100Ru in Hawaiian OIB. For instance, a CMER composition has been modelled using metal-silicate partition coefficients of HSE and W extrapolated to CMB conditions (Extended Data Table 2)35,36. However, incorporation of a CMER (Ru/W < 0.03) will lead to imperceptible changes in the Ru composition in the mantle source regardless of the ε100Ru value chosen for the core (Fig. 3b, dashed line).

Alternative models not invoking interaction between Earth’s core and mantle have also been suggested to explain observed negative μ182W. Negative μ182W may characterize an early enriched silicate reservoir, evolving with low Hf/W (ref. 37). In a Hadean, enriched mantle reservoir, for example, μ182W would be expected to correlate with μ142Nd because fractionation of Hf/W and Sm/Nd are tightly linked during silicate differentiation28, but negative μ142Nd have not been observed for any plume-related rocks so far38,39,40. Potentially, μ142Nd and μ182W systematics may be decoupled during the formation and differentiation of Hadean proto-crust13. However, the influence of Hadean recycled crust on the ε100Ru signature would be negligible because Ru is strongly depleted in the crust compared to the mantle (Archean upper continental crust 0.51 ng g−1, ref. 41; mantle 7.4 ng g−1 Ru, ref. 42). On the other hand, negative μ182W in OIB have also been interpreted to reflect remnants of late, impactor core material preserved in the mantle8,11. The incorporation of core material derived from an s-process-enriched late impactor, stranded in the mantle, could hypothetically explain the coupled isotope systematics of Hawaiian OIBs. Yet, the last impactors incorporated into Earth’s mantle as part of the late veneer, that are more likely to contribute to the OIB source, are required to have ε100Ru < 0 to lower the ε100Ru > 0 composition of the Eoarchean mantle to the present day mantle value (ε100Ru ≈ 0)6 and, therefore, do not have an appropriate composition. As such, the Earth’s core is at present the most viable source to explain the combined origin of positive ε100Ru and negative μ182W values observed in OIBs.

Methods

Samples

Samples analysed in this study comprise basalts, picrites and ultramafic cumulates associated with the Hawaii, Réunion, Galápagos and Iceland mantle plumes. Hawaiian samples with National Museum of Natural History catalogue numbers were provided by the Department of Mineral Science of the Smithsonian Institute (Data Repository). Samples from Kilauea are ultramafic cumulate samples from the 1981 drilling project on the Kilauea Iki lava lake46 for which W and He isotope ratios have been previously determined5,47. Furthermore, we determined the Ru isotopic compositions for submarine basalts and picrites from the Kama’ehuakanaloa (Loihi) volcano, for which W and He isotope data have been determined previously1,8,22,48. We also determined combined W and Ru isotope data for a new sample (12787) collected from the summit of the Kama’ehuakanaloa seamount. We selected samples from Kauai based on high 3He/4He ratios reported for olivine basalts from the Napali Member, formed during the shield volcanic stage of Kauaii49. For some historic samples from Kauaii coordinates were not available50. Locations of these samples were determined based on sample descriptions from the Smithsonian sample catalogue and found to be situated well within the outcrop area of the Napali Member. Tungsten isotope data were determined for all samples from Kauaii and further Ru isotope data for samples 11k and K-8. We also provide the Ru isotopic composition of a sample from Oahu (KOO-17a), for which 3He/4He values have been previously determined51. Extra Ru isotope data were determined for a 17.5 Ma picritic komatiite that formed as a part of the aseismic ridge of the Galápagos hotspot track accreted to the coast of Burica Peninsula in Costa Rica52. W isotope data for this sample have been previously determined53. We conducted W isotope measurements for two basalts from Fernandina (Galápagos) to augment the existing W dataset for this island. The basalts were subaerially deposited during the 1995 (Fe 15-23) and 2009 (Fe 15-12) eruptions. We determined the W and Ru isotopic composition of a basalt sample from the 1977 eruption of the Piton de la Fournaise (REU 14-31), and the W isotope composition for two samples from La Réunion, for which W isotope data have been previously reported2. Last, we determined the Ru isotopic composition for a set of high 3He/4He picrites from Baffin Island, representing the oldest volcanic expressions of the Iceland plume21.

Besides lavas from OIB settings, we analysed a variety of other mafic and ultramafic samples to validate our analytical procedure and further constrain the composition of the upper mantle. To compare measurement uncertainties and reproducibility to previous studies, we analysed the commercially available pegmatitic pyroxenite OREAS 684 (Ore Research & Exploration Pty Ltd) sourced from Merensky Reef ores from the 2.05 billion-year (Gyr) Bushveld Complex. Sample IR1513 is a carboniferous picrite collected from the Gönnern quarry in Hessia, Germany. These submarine volcanic rocks were probably deposited in a back-arc environment and are characterized by trace element compositions resembling modern E-MORB54. Sample EIF-1 is a composite sample of lherzolite-harzburgite mantle xenoliths from the West Eifel volcanic field. The 3.7-Gyr-old ultramafic meta-dunite sample TM220719 1A has been sampled from a dunite lens in the NW-arm of the Isua supracrustal belt and has been variably interpreted as thrust-emplaced mantle rocks55 or cumulates56,57. The sample location is equivalent to sample 194907 previously constrained for Ru isotopes in ref. 6.

Sample preparation

Whole rock material was processed by removing the weathering crust using a metal saw. Larger samples were then cut into smaller than 2-cm-thick slabs. All saw marks were removed by polishing with silicon-carbon sandpaper on a polishing table and subsequently washed with water. For small and brittle sample pieces the cutting process was omitted. Samples were then wrapped in several layers of plastic foil to avoid metal contamination during subsequent crushing using a hydraulic press. The samples were crushed until all pieces were smaller than 5 mm and subsequently milled to produce a fine powder (less than 125 μm) using an agate ball mill. The Baffin Island picrites were instead crushed in a tungsten-carbide jaw crusher before milling in an agate ball mill. The basic laboratory procedures for Ru isotopes are described elsewhere6,27,58. The overall low Ru concentration of the samples (0.25–1.7 ng g−1) as well as low and inconsistent Ru procedural yields reported in previous studies (that is, 20–90% ref. 23; less than 60–80%, ref. 58; 40–80%, ref. 6 and 30–80%, ref. 59) necessitated substantial improvements to the overall procedure and measurement setup published in the recent literature. Throughout the study, double-distilled acids (Savillex, DST-1000) and 18.2 MΩ cm−1 water (Merck Millipore) were used to process the samples. Commercially available high-purity HBr (Romil-UpA) was used during the early stages of the study. Yet, we decided to switch to HBr purified in-house (distilled five times) to improve Mo blanks (data in Extended Data Table 1 marked accordingly). All extra reagents are commercially available and a detailed list is provided in Extended Data Table 3. For each sample, 20–240 g of sample powder was preconcentrated using a nickel sulfide fire assay (NiS-fa). For the NiS-fa 20-g aliquots of sample powder were added to 130-ml porcelain crucibles with the addition of 26 g of anhydrous borax, 14 g of sodium carbonate, 1 g of nickel and 0.75 g of sulfur. The samples were thoroughly homogenized using a glass stirring rod, placed in a preheated muffle furnace and fluxed at 1,020 °C for 90 min. The samples were then removed from the furnace and quenched in room-temperature air. A NiS bead, usually weighing between 1.43 and 1.47 g was removed from the glass matrix using alumina mortar and pestle. Without crushing, each bead was dissolved in 20 ml of concentrated HCl at 130 °C for 12 h. After complete drying, this step was repeated using 25 ml of concentrated HCl and 30 ml of 6 M HCl. During the last step, 50 μl of H2O2 were added to the sample several times until no residues were visible. This usually required a total of 50–250 μl of H2O2. The samples were fully dried down followed by 10 ml of H2O, added in two consecutive steps. The sample is finally dissolved in 20 ml 0.2 M HCl and purified using the cation exchange procedure6. For this, each digestion was split and loaded on two separate glass columns (1 cm inner diameter; 30 cm length) filled with 20 ml of AG 50 W-X8 (100–200 mesh, BioRad) cation exchange resin. The platinum group elements were separated from the Ni matrix using 14 ml of 0.2 M HCl. The latter was subsequently removed in five column volumes of 6 M HCl. Split samples were recombined and evaporated at 100 °C. The samples were dissolved in 4 ml of 0.2 M HCl and passed through 2-ml cation exchange columns (BioRad Poly-Prep). This cleanup chemistry was repeated a second time to ensure the quantitative removal of Ni. This procedure is imperative because NiAr interferences later during mass spectrometric analysis will prohibit precise quantification of Ru isotope ratios during the measurement procedure for analyses with Ni/Ru greater than 1 × 10−4 (Extended Data Fig. 2). Finally, the Ru fraction was purified using a distillation procedure. Here, the Ru fraction was dissolved in 1 ml of concentrated H2SO4 and 1.24 ml of H2O and transferred into a 30-ml Savillex beaker fitted with a 33 mm impinger closure (oxidation vessel). To each oxidation vessel 1 ml of 0.457 g ml−1 aqueous CrO3 solution and 0.1 ml of concentrated HNO3 were added. The beaker was connected to a 20-ml Savillex beaker with impinger closure (reduction vessel) through a one-eighth of an inch diameter PFA (perfluoroalkoxy) tubing. The reduction vessel was filled with 10 ml of 10% HBr solution and connected to a chemical-resistant diaphragm vacuum pump (Rocker Chemker 411) through silicone tubing. A 2-l washing bottle filled with a weak KOH solution was interconnected to reduce the amount of acid vapour in the vacuum pump. With this setup, up to three samples could be distilled at the same time. The vacuum pump was set to a constant vacuum of 550 mmHg. A flow controller (PN 10 one-eighth of an inch diameter EM Technik) was connected upstream of the oxidation vessel to control the airflow. The controller was set so that a constant stream of air bubbled through the reduction beaker at a rate of 300–350 bubbles per min. The oxidation beaker was uniformly heated from the bottom to the base of the impinger closure in a PFA-coated aluminium block. A schematic of the distillation setup is provided in Extended Data Fig. 3. To ensure an even temperature distribution, the closure, as well as the transfer tubing, were wrapped in aluminium foil and the entire hotplate was covered with an extra layer of foil. The oxidation vessel was heated to 90 °C for 3 h. The vacuum was slowly released on completion of the distillation. The HBr solution containing the samples was evaporated for 3.5 h at 130 °C. Subsequently, 1 ml of 2 M HCl was added to each sample and evaporated at 100 °C. Finally, appropriate amounts of 0.28 M HNO3 were added to obtain a 40 μg g−1 Ru solution for analysis. We obtained a total average procedural blank of 428 ± 67 pg based on five blank samples passed as unknowns through the entire chemical purification procedure. For samples with the lowest Ru concentrations processed in our study (0.25 ng g−1) this equates to a blank contribution of 7.6%. Distillation yields were determined on 1‰ aliquots taken before and after distillation to be 60–100% with an average of 87% based on 109 individual distillations and are significantly higher than those reported in previous studies (above). The improvement in distillation yield can be attributed to two main factors. First, the volatile RuO4 rapidly decomposes under hot humid conditions to form solid, insoluble RuO2 (refs. 60,61). In this context, we found significantly improved distillation yields when oxidizing and volatile acids were added to the oxidizing vessel62. The addition of HNO3 and resulting HNO3 vapour leads to significantly improved stability of volatile Ru species when compared to H2O vapours61. Second, uniform heating and high extraction volumes of the vacuum pump inhibit any condensation in the oxidation vessel. Initial testing at lower extraction rates with no thermal insulation from Al foil fractions of Ru could frequently be detected in water droplets deposited in the closure of the oxidation vessel.

Ru isotope measurement

The Ru isotopic compositions of samples and reference materials were determined on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Neptune Plus multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (MC–ICP–MS) at the Department of Geochemistry and Isotope Geology of the University of Göttingen. A Teledyne Cetac Aridus III desolvating nebulizer equipped with the QuickWash3 accessory was used as the sample introduction system with a fixed capillary PFA nebulizer tip (ESI, uptake rate 68 μl min−1). All measurements were performed using Ni X-type skimmer cones and standard Ni sampler cones. This yielded ion beam intensities ranging from 1 × 10−10 to 1.35 × 10−10 A for a 40 ng g−1 Ru solution for oxide formation rates of Ce/CeO less than 5% (typically 2–3%). Use of X-type skimmer cones increased the formation rate of NiAr (Extended Data Fig. 2). Ni/Ru ratios were monitored before measurement and found to be below 10−4 for all samples. The Ru isotope measurements were conducted in static mode with simultaneous measurement of all stable Ru isotopes and masses 97 and 105 to monitor isobaric mass interferences of Mo and Pd. Faraday cups were connected to 1011 Ω feedback resistors for most masses. Amplifiers with 1012 Ω resistors were used for mass 98 and 1013 Ω resistors for masses 97 and 105. Each sample measurement was bracketed by a 40 ng g−1 Ru single-element reference solution (CPI International). Measurements of sample and standard solutions comprised 100 measurement cycles with 8.4 s of integration time each. For a single analysis, about 45 ng of Ru were required. Sample and standard measurements were preceded by on-peak baseline measurements of 0.28 M HNO3 consisting of 40 cycles with 8.4 s of integration time. Raw intensity data were corrected offline for baseline and instrument-induced mass fractionation using a Python-based script. The script first subtracts on-peak baseline measurements from measured intensities. Afterwards, mass fractionation was corrected using the exponential law relative to a constant 99Ru/101Ru value of 0.7450754 (ref. 63), Interference corrections for Pd and Mo were applied, followed by a 2σ outlier test. Isotope variations were then calculated as εiRu = ((iRu/101Ru)sample/(iRu/101Ru)standard − 1) × 10,000 against the CPI bracketing standard. The external reproducibility (2σ) was determined through repeated analysis of certified reference material OREAS 684 (total of 72 single measurements, 13 individual digestions). This yielded an external reproducibility (2 s.d.) of ±0.55 for ε96Ru, ±0.76 for ε98Ru, ±0.13 for ε100Ru, ±0.18 for ε102Ru and ±0.42 for ε104Ru (Supplementary Table 1). The external reproducibility of individual isotopes is comparable to those of previous studies6. Variably high ε96Ru values in standards and reference materials are due to isobaric interferences of 96Zr, which could not be monitored during sample measurement and therefore remain uncorrected.

Ruthenium concentrations

In addition to Ru isotope data, we provide an estimate of the Ru concentration of the samples measured in Extended Data Table 1. Ru concentrations were determined on 1‰ sample aliquots of individual NiS digestions, taken after the first cation chemistry. Aliquots were diluted in 0.5 ml of 0.28 M HNO3 and measured alongside a set of four gravimetrically calibrated HSE standards on a Thermo iCAP quadrupole ICP-MS at the University of Göttingen. The Ru concentrations provided are purely informational values as the samples will have probably already lost Ru during NiS digestion and cation chemistry and only provide an estimate of the Ru concentration. The uncertainties provided reflect the standard deviation of repeated digestions of the same sample. Samples for which no error is provided have only been digested once and were found to have insufficiently low Ru concentrations for further isotope analysis.

W isotope procedures

The W isotopic compositions of samples and reference materials were determined on a Thermo Fisher Scientific Neptune Plus MC–ICP–MS at the Department of Geochemistry and Isotope Geology of the University of Göttingen. The laboratory and measurement procedures have been described in detail elswhere53. The sample preparation procedures for W introduce varying effects on 183W (refs. 64,65). Although negative μ183W values measured in this study indicate a similar effect on our samples (Extended Data Table 1), we used 186W/184W ratios to correct for mass bias to avoid any influence of the 183W effect on μ182W values. We have previously shown that normalization to 186W/183W can still produce valid μ182W values if correction factors are applied53,65, indicating that no unaccounted effects influence the isotopic composition of W. W isotope ratios are reported as μ182W, which is defined as (182W/184Wsample / 182W/184WNIST3163 − 1) × 1,000,000.

For each sample, between 3 and 12 individual measurements were conducted based on the sample concentration. The external reproducibility was calculated by repeated measurements of in-house reference basalt ‘Me21’, which were measured at the beginning and the end of every measurement sequence. The external μ182W reproducibility (2 s.d.) is 4.8 ppm for basalt Me21 (n = 41) for triplet measurements. For sextuplet analysis, the reproducibility was improved to 3.6 ppm for basalt Me21 (n = 14) and to 3.3 ppm for any sample analysed nine times or more (n = 8). All μ182W data measured in this study are provided in Extended Data Table 1.

Furthermore, we reanalysed sample KK 25-4 from the Kama’ehauakanaloa (Loihi) submarine volcano (Hawaii)8 and samples REU 1001-053 and REU 1406-24.9a (La Réunion)2, for which data have previously been reported. For sample KK 25-4 our μ182W value of −16.3 ± 3.6 is in good agreement with the previously reported value of −13.1 ± 6.7 (ref. 8). Samples REU 1001-053 and REU 1406-24.9a have μ182W values of −1.5 ± 3.6 and −8.8 ± 3.6, respectively. Their isotopic compositions are significantly less anomalous than those previously reported (μ182W = −15.7 ± 3.2 and −20.2 ± 5.1, respectively2). Discrepancies between W isotope ratios measured by Neptune MC–ICP–MS and those measured by thermo ionization mass spectrometry have been reported in the past8,66. Indeed, μ182W data for La Réunion reported in further studies indicate more restricted μ182W variations between 0 and −10 (refs. 45,67). Our new data confirm that μ182W anomalies in basalts from La Réunion probably do not significantly exceed values of −10.

We also constrained W isotope data for two new samples from Fernandina (Galápagos) where some of the most negative μ182W values have been previously reported (μ182W = −22.7)1. The new samples, Fe 15-12 and Fe 15-23, have μ182W of −14.7 ± 3.6 and −17.5 ± 3.6, respectively. They confirm the anomalous W isotope composition of Fernandina basalts, however, they cannot be directly compared to those previously analysed due to unknown age relationships. For this study, we define the range of μ182W variations in the global OIB record by the most anomalous sample independently constrained in many studies. As such we assume a range of μ182W = 0 to −20 based on the sample OFU-04-14 from Samoa (μ182W = −20.2 ± 3.9 and −17.3 ± 4.5, refs. 5,23).

Data availability

All data produced in this study are available in Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1 and are archived in the DIGIS geochemical data repository available at https://doi.org/10.5880/digis.2024.003. Source data are provided with this paper.

Change history

29 May 2025

In the version of the article initially published, in the first paragraph, the text “t1/2 = 8.9 thousand years ago (Ma)” was incorrect and has now been amended to “t1/2 = 8.9 million years” in the HTML and PDF versions of the article.

References

Mundl-Petermeier, A. et al. Anomalous 182W in high 3He/4He ocean island basalts: fingerprints of Earth’s core? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 271, 194–211 (2020).

Rizo, H. et al. 182W evidence for core-mantle interaction in the source of mantle plumes. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 11, 6–11 (2019).

Horton, F. et al. Highest terrestrial 3He/4He credibly from the core. Nature 623, 90–94 (2023).

Walker, R. J., Morgan, J. W. & Horan, M. F. Osmium-187 enrichment in some plumes: evidence for core-mantle interaction? Science 269, 819–822 (1995).

Mundl, A. et al. Tungsten-182 heterogeneity in modern ocean island basalts. Science 356, 66–69 (2017).

Fischer-Gödde, M. et al. Ruthenium isotope vestige of Earth’s pre-late-veneer mantle preserved in Archaean rocks. Nature 579, 240–244 (2020).

Vockenhuber, C. et al. New half-life measurement of 182Hf: improved chronometer for the early solar system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 172501 (2004).

Archer, G. J. et al. Origin of W anomalies in ocean island basalts. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 24, e2022GC010688 (2023).

Bouhifd, M. A., Jephcoat, A. P., Heber, V. S. & Kelley, S. P. Helium in Earth’s early core. Nat. Geosci. 6, 982–986 (2013).

Ferrick, A. L. & Korenaga, J. Long-term core–mantle interaction explains W-He isotope heterogeneities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2215903120 (2023).

Korenaga, J. & Marchi, S. Vestiges of impact-driven three-phase mixing in the chemistry and structure of Earth’s mantle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2309181120 (2023).

Willhite, L. N., Finlayson, V. A. & Walker, R. J. Evolution of tungsten isotope systematics in the Mauna Kea volcano provides new constraints on anomalous µ182W and high 3He/4He in the mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 640, 118795 (2024).

Tusch, J. et al. Long-term preservation of Hadean protocrust in Earth’s mantle. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2120241119 (2022).

Ireland, T. J., Walker, R. J. & Brandon, A. D. 186Os-187Os systematics of Hawaiian picrites revisited: new insights into Os isotopic variations in ocean island basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 4456–4475 (2011).

Bennett, V. C., Norman, M. D. & Garcia, M. O. Rhenium and platinum group element abundances correlated with mantle source components in Hawaiian picrites: sulphides in the plume. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 183, 513–526 (2000).

Yoshino, T., Makino, Y., Suzuki, T. & Hirata, T. Grain boundary diffusion of W in lower mantle phase with implications for isotopic heterogeneity in oceanic island basalts by core-mantle interactions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 530, 115887 (2020).

Kaare-Rasmussen, J. et al. Tungsten isotopes in Baffin Island lavas: evidence of Iceland plume evolution. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 28, 7–12 (2023).

Walker, R. J. et al. 182W and 187Os constraints on the origin of siderophile isotopic heterogeneity in the mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 363, 15–39 (2023).

Rubie, D. C. et al. Highly siderophile elements were stripped from Earth’s mantle by iron sulfide segregation. Science 353, 1141–1144 (2016).

Chou, C. L. Fractionation of siderophile elements in the Earth’s upper mantle. In Proc. 9th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 219–230 (Pergamon Press, 1978).

Starkey, N. A. et al. Helium isotopes in early Iceland plume picrites: constraints on the composition of high 3He/4He mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 277, 91–100 (2009).

Stubbs, D. The Tungsten Isotopic Evolution of the Silicate Earth 143–217. PhD thesis, Univ. of Bristol (2021).

Bermingham, K. R. & Walker, R. J. The ruthenium isotopic composition of the oceanic mantle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 474, 466–473 (2017).

Dauphas, N., Hopp, T. & Nesvorný, D. Bayesian inference on the isotopic building blocks of Mars and Earth. Icarus 408, 115805 (2024).

Render, J., Brennecka, G. A., Burkhardt, C. & Kleine, T. Solar System evolution and terrestrial planet accretion determined by Zr isotopic signatures of meteorites. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 595, 117748 (2022).

Budde, G., Burkhardt, C. & Kleine, T. Molybdenum isotopic evidence for the late accretion of outer Solar System material to Earth. Nat. Astron. 3, 736–741 (2019).

Fischer-Gödde, M. & Kleine, T. Ruthenium isotopic evidence for an inner Solar System origin of the late veneer. Nature 541, 525–527 (2017).

Touboul, M., Puchtel, I. S. & Walker, R. J. 182W Evidence for long-term preservation of early mantle differentiation products. Science 355, 1065–1069 (2012).

McDonough, W. F. in Treatise on Geochemistry Vol. 2 (eds Holland H. D. & Turekian, K. K.) 547–568 (Elsevier, 2003).

Waters, C. L. et al. Sulfide mantle source heterogeneity recorded in basaltic lavas from the Azores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 268, 422–445 (2020).

Day, J. M. D. Hotspot volcanism and highly siderophile elements. Chem. Geol. 341, 50–74 (2013).

Mungall, J. & Brenan, J. Partitioning of platinum-group elements and Au between sulfide liquid and basalt and the origins of mantle-crust fractionation of the chalcophile elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 125, 265–289 (2014).

Badro, J., Siebert, J. & Nimmo, F. An early geodynamo driven by exsolution of mantle components from Earth’s core. Nature 536, 326–328 (2016).

Chabot, N. L., Wollack, E. A., Humayun, M. & Shank, E. M. The effect of oxygen as a light element in metallic liquids on partitioning behavior. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 530–546 (2015).

Mann, U., Frost, D. J., Rubie, D. C., Becker, H. & Audétat, A. Partitioning of Ru, Rh, Pd, Re, Ir and Pt between liquid metal and silicate at high pressures and high temperatures—implications for the origin of highly siderophile element concentrations in the Earth’s mantle. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 84, 593–613 (2012).

Suer, T. A. et al. Reconciling metal–silicate partitioning and late accretion in the Earth. Nat. Commun. 12, 2913 (2021).

Puchtel, I. S., Blichert-Toft, J., Touboul, M., Horan, M. F. & Walker, R. J. The coupled 182W-142Nd record of early terrestrial mantle differentiation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 17, 2168–2193 (2016).

de Leeuw, G. A. M., Ellam, R. M., Stuart, F. M. & Carlson, R. W. 142Nd/144Nd inferences on the nature and origin of the source of high 3He/4He magmas. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 472, 62–68 (2017).

Horan, M. F. et al. Tracking Hadean processes in modern basalts with 142-Neodymium. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 484, 184–191 (2018).

Jackson, M. G. & Carlson, R. W. Homogeneous superchondritic 142Nd/144Nd in the mid-ocean ridge basalt and ocean island basalt mantle. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 13, Q06011 (2012).

Chen, K. et al. Platinum-group element abundances and Re–Os isotopic systematics of the upper continental crust through time: evidence from glacial diamictites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 191, 1–16 (2016).

Becker, H. et al. Highly siderophile element composition of the Earth’s primitive upper mantle: constraints from new data on peridotite massifs and xenoliths. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 4528–4550 (2006).

Hopp, T., Budde, G. & Kleine, T. Heterogeneous accretion of Earth inferred from Mo-Ru isotope systematics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 534, 116065 (2020).

Vermeesch, P. IsoplotR: a free and open toolbox for geochronology. Geosci. Front. 9, 1479–1493 (2018).

Jansen, M. W. et al. Upper mantle control on the W isotope record of shallow level plume and intraplate volcanic settings. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 585, 117507 (2022).

Helz, R. T. & Wright, T. L. Drilling Report and Core Logs of the 1981 Drilling of Kilauea Iki Lava Lake. Open-file report 83-326 (USGS, 1981).

Kurz, M. D., Jenkins, W. J. & Hart, S. R. Helium isotopic systematics of oceanic islands and mantle heterogeneity. Nature 297, 43–47 (1982).

Kent, A. J. R. et al. Widespread assimilation of a seawater-derived component at Loihi seamount, Hawaii. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 2749–2761 (1999).

Mukhopadhyay, S., Lassiter, J. C., Farley, K. A. & Bogue, S. W. Geochemistry of Kauai shield-stage lavas: implications for the chemical evolution of the Hawaiian plume. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, 1009 (2003).

Cross, W. Lavas of Hawaii and their Relations. USGS professional paper 88 (USGS, 1915).

Roden, M. F., Trull, T., Hart, S. R. & Frey, F. A. New He, Nd, Pb, and Sr isotopic constraints on the constitution of the Hawaiian plume: results from Koolau Volcano, Oahu, Hawaii, USA. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 1431–1440 (1994).

Appel, H., Wörner, G., Alvarado, G., Rundle, C. & Kussmaul, S. Age relations in igneous rocks from Costa Rica. Profil 7, 63–69 (1994).

Messling, N., Wörner, G. & Willbold, M. Ancient mantle plume components constrained by tungsten isotope variability in arc lavas. Geochem. Perspect. Lett. 26, 31–35 (2023).

Schmincke, H. U. & Sunkel, G. Carboniferous submarine volcanism at Herbornseelbach (Lahn-Dill area, Germany). Geol. Rundschau 76, 709–734 (1987).

Nutman, A. P., Bennett, V. C., Friend, C. R. L. & Yi, K. Eoarchean contrasting ultra-high-pressure to low-pressure metamorphisms (<250 to >1000 °C/GPa) explained by tectonic plate convergence in deep time. Precambrian Res. 344, 105770 (2020).

Waterton, P. et al. No mantle residues in the Isua Supracrustal Belt. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 579, 117348 (2022).

Zuo, J. et al. Earth’s earliest phaneritic ultramafic rocks: mantle slices or crustal cumulates? Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 23, e2022GC010519 (2022).

Fischer-Gödde, M., Burkhardt, C., Kruijer, T. S. & Kleine, T. Ru isotope heterogeneity in the solar protoplanetary disk. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 168, 151–171 (2015).

Hopp, T., Fischer-Gödde, M. & Kleine, T. Ruthenium isotope fractionation in protoplanetary cores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 223, 75–89 (2018).

Avtokratova, T. D. in Analytical Chemistry of Ruthenium Ch. 4, 131–157 (1963).

Yoshida, N., Ono, T., Yoshida, R., Amano, Y. & Abe, H. Decomposition behavior of gaseous ruthenium tetroxide under atmospheric conditions assuming evaporation to dryness accident of high-level liquid waste. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 57, 1256–1264 (2020).

Koda, Y. Distillation of ruthenium tetraoxide with volatile acids. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 25, 314–315 (1963).

Chen, J. H., Papanastassiou, D. A. & Wasserburg, G. J. Ruthenium endemic isotope effects in chondrites and differentiated meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 3851–3862 (2010).

Tusch, J. et al. Uniform 182W isotope compositions in Eoarchean rocks from the Isua region, SW Greenland: the role of early silicate differentiation and missing late veneer. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 257, 284–310 (2019).

Budde, G., Archer, G. J., Tissot, F. L. H., Tappe, S. & Kleine, T. Origin of the analytical 183 W effect and its implications for tungsten isotope analyses. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 37, 2005–2021 (2022).

Kruijer, T. S. & Kleine, T. No 182W excess in the Ontong Java Plateau source. Chem. Geol. 485, 24–31 (2018).

Peters, B. J., Mundl-Petermeier, A., Carlson, R. W., Walker, R. J. & Day, J. M. D. Combined lithophile-siderophile isotopic constraints on Hadean processes preserved in Ocean Island basalt sources. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 22, e2020GC009479 (2021).

Savina, M. R. et al. Extinct technetium in silicon carbide stardust grains: implications for stellar nucleosynthesis. Science 303, 649–653 (2004).

Hopp, T., Fischer-Gödde, M. & Kleine, T. Ruthenium stable isotope measurements by double spike MC-ICPMS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 31, 1515–1526 (2016).

Fischer-Gödde, M., Becker, H. & Wombacher, F. Rhodium, gold and other highly siderophile elements in orogenic peridotites and peridotite xenoliths. Chem. Geol. 280, 365–383 (2011).

Palme, H. & O’Neill, H. S. Cosmochemical Estimates of Mantle Composition. Treatise on Geochemistry 2nd edn, Vol. 3 (eds Turekian, K. K. & Holland, H. D.) 1–39 (Elsevier, 2014).

Fischer-Gödde, M., Becker, H. & Wombacher, F. Rhodium, gold and other highly siderophile element abundances in chondritic meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 356–379 (2010).

Horan, M. F., Walker, R. J., Morgan, J. W., Grossman, J. N. & Rubin, A. E. Highly siderophile elements in chondrites. Chem. Geol. 196, 27–42 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Department of Mineral Sciences at the Smithsonian Institute, G. Wörner and A. Di Muro for providing sample material. The Baffin Island samples were collected in 1996 by I. Snape, C. Cole and S. Brown during an Edinburgh University expedition to Baffin Island supported by a grant from the Laidlaw-Hall Trust. The authors thank B.-M. Elfers for support with method development, J. Krayer for sample preparation and D. Hoffmann, S. Metje and N. Lockhoff for technical and analytical laboratory support. This research was funded through DFG grant WI 3579/3-1 within the priority programme SPP 1833 ‘Building a Habitable Earth’ and grant WI 3579/5-1 awarded to M.W.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Georg-August-Universität Göttingen.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Thorsten Kleine and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

This file contains the Ru isotope data of reference materials measured throughout this study. This includes data for individual analysis of certified reference material OREAS 684 and in-house reference samples EIF-1, 1513 and TM220719 1A.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Messling, N., Willbold, M., Kallas, L. et al. Ru and W isotope systematics in ocean island basalts reveals core leakage. Nature 642, 376–380 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09003-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09003-0