Abstract

The fusion of non-Abelian anyons is a fundamental operation in measurement-only topological quantum computation1. In one-dimensional topological superconductors (1DTSs)2,3,4, fusion amounts to a determination of the shared fermion parity of Majorana zero modes (MZMs). Here we introduce a device architecture5 that is compatible with future tests of fusion rules. We implement a single-shot interferometric measurement of fermion parity6,7,8,9,10,11 in indium arsenide–aluminium heterostructures with a gate-defined superconducting nanowire12,13,14. The interferometer is formed by tunnel-coupling the proximitized nanowire to quantum dots. The nanowire causes a state-dependent shift of the quantum capacitance of these quantum dots of up to 1 fF. Our quantum-capacitance measurements show flux h/2e-periodic bimodality with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 1 in 3.6 μs at optimal flux values. From the time traces of the quantum-capacitance measurements, we extract a dwell time in the two associated states that is longer than 1 ms at in-plane magnetic fields of approximately 2 T. We discuss the interpretation of our measurements in terms of both topologically trivial and non-trivial origins. The large capacitance shift and long poisoning time enable a parity measurement with an assignment error probability of 1%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

To make use of a topological phase for quantum computation, it is crucial to manipulate and measure the topological charge. This can be achieved through protected operations such as braiding and fusing non-Abelian anyons, which offer exponential suppression of errors induced by local noise sources and a discrete set of native operations15,16,17. Protocols for measurement-only topological quantum computation simplify these operations, reducing them to fusion alone1,5. This fundamental measurement is sufficient to enact all topologically protected operations. New error-correction schemes have been developed to take advantage of these operations18,19,20. The robustness against errors and simplicity of control offered by this approach make measurement-based topological qubits a promising path towards utility-scale quantum computation, in which managing the interactions of millions of qubits is necessary21,22,23,24.

1DTSs2,3,4 are a promising platform for building topological qubits. Quantum information is stored in the fermion parity of MZMs localized at the ends of superconducting wires and projective measurements of the fermion parity are used to process quantum information and perform qubit-state readout25,26. The fermion parity shared by a pair of MZMs can be determined through an interferometric measurement3,6,7,8,9. Several conceptual designs for topological qubits incorporate such interferometers5,10,11,27. These proposals require time-resolved measurements of the fermion parity in the interference loop, which cannot be accomplished with dc transport measurements of the time-averaged fermion parity28.

In this paper, we demonstrate such a time-resolved measurement, thereby validating a necessary ingredient of topological quantum computation. The measurement technique is based on examining the quantum capacitance CQ of a quantum dot coupled to the nanowire5,29,30,31 (Fig. 1) and allows determination of the parity in a single shot. We achieve an assignment error probability of 1% for optimal measurement time. By itself, this measurement does not unequivocally distinguish between MZMs in the topological phase and fine-tuned low-energy Andreev bound states in the trivial phase32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40 but it does require the low-energy state to be supported at both ends of the wire and very weakly coupled to other low-energy fermionic states. Moreover, it provides a measurement of the state’s energy with single-μeV resolution. These features of the measurement strongly constrain the nature of the low-energy state.

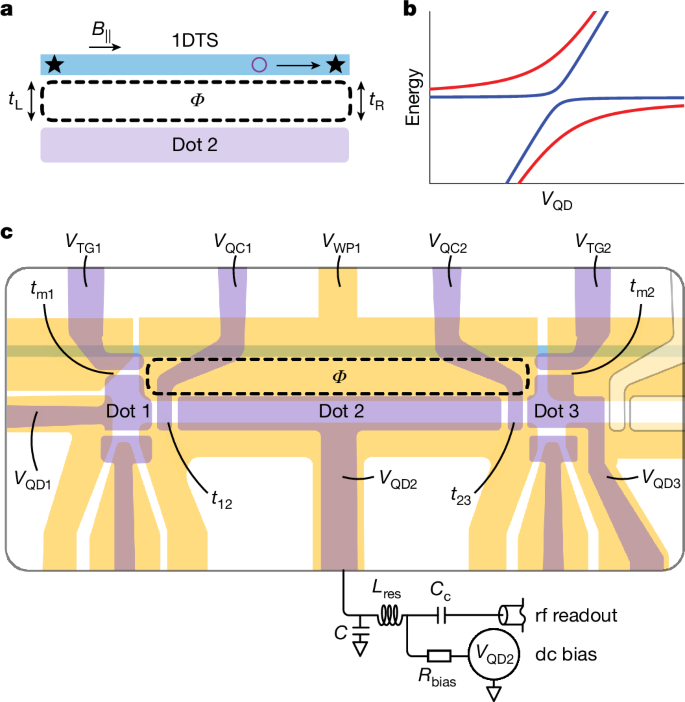

a, Idealized model of the system. A nanowire tuned into a 1DTS state hosts MZMs at its ends, depicted by stars. A quantum dot is tunably coupled to the MZMs by tunnel couplings tL and tR, forming an interferometer, which is sensitive to the magnetic flux Φ enclosed by the dashed line and the combined fermion parity Z of the dot–MZMs system. Poisoning by a quasiparticle (purple circle) flips the parity. b, Example energy spectra of the interferometer with total parity Z = −1 (red) and Z = +1 (blue) in the vicinity of the avoided crossing between the states with N and N + 1 electrons on the dot, as a function of the plunger voltage on the quantum dot; see equation (2). c, Gate layout for the interference loop formed by the triple quantum dot and the gate-defined nanowire (light green). Voltage VWP1 is applied to the wire plunger gate (yellow) and voltage VQD2 is applied to the dot 2 plunger gate (purple). The effective couplings tL and tR of panel a depend on the couplings tm1, t12 and tm2, t23 and detuning of quantum dots 1 and 3, respectively. Quantum dot 2 is capacitively coupled to an off-chip resonator chip for dispersive gate sensing and CQ measurement, which also includes a bias tee for applying dc voltages.

Device design and setup

We introduce a device architecture enabling projective measurements of fermion parity5,10,11,27,29,41,42. The device comprises two primary components, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The first component is a nanowire that will have MZMs at its ends if it is in a 1DTS state. The second component consists of quantum dots, which are designed to couple pairs of MZMs in an interferometric loop.

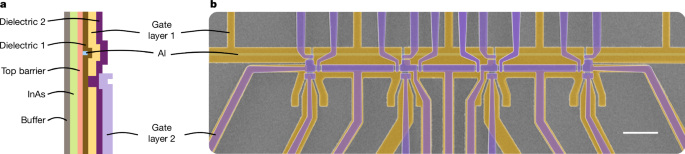

The nanowire in this device is based on a gated superconductor–semiconductor heterostructure and defined by a narrow Al strip that suppresses depletion underneath it12,13,14. Device fabrication and details of the heterostructure design are discussed in Sections 1.2 and 1.3 of the Supplementary Information, respectively. The Al strip is grounded and continuous throughout, but there are separate ‘plunger’ gates that define five sections of the wire. One of them is shown schematically in Fig. 1c and all five are visible in the scanning electron microscopy image in Fig. 2b. Although there are no breaks in the Al, the plunger gates independently control the density in each section. (See Supplementary Fig. 1 and Section 1.1 of the Supplementary Information for a complete device schematic and gate-naming convention; throughout the paper, Vi refers to the dc voltage applied to gate i.) A topological qubit would require tuning the second and fourth segments, each of length L ≈ 3 μm, into the 1DTS state, whereas the other three would be fully depleted underneath the Al strip (see Supplementary Fig. 1 for details). Here we focus on the second section shown in Fig. 1c and implement a parity measurement using its associated interferometer.

a, Cross-section of the gate-defined superconducting nanowire device design. b, Scanning electron microscopy image with the aluminium strip (blue), first gate layer (yellow) and second gate layer (purple) indicated in false colour. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Our readout circuit is based on dispersive gate sensing of a triple quantum dot interferometer (TQDI): three electrostatically defined quantum dots that, together with the second nanowire section, form a loop threaded by a flux, Φ (Fig. 1a,c). We control Φ by varying the out-of-plane magnetic field, B⊥. The TQDI has two smaller dots (dots 1 and 3), which serve as tunable couplers providing control over, respectively, the tunnel couplings tL and tR. The smaller dots are connected to the ends of the 1DTS through tunnel couplings tmi, in which i = 1, 2, and to the long quantum dot (dot 2) that connects to dot 1 and dot 3 through tunnel couplings t12 and t23, respectively. The quantum capacitance, CQ, of dot 2 is read out through dispersive gate sensing using an off-chip resonator circuit in a reflectometry setup43; a detailed description is given in Section 1.4 of the Supplementary Information.

We have developed an rf-based quantum dot–MZM tuning protocol that we use to balance the arms of the interferometer. We measure CQ in a configuration in which one of the small dots is maximally detuned, effectively interrupting the loop. Comparing these measurements with simulations, we extract the couplings t12, t23, tm1 and tm2 (see Section 2.5 of the Supplementary Information). This measurement protocol expands on the dc transport techniques proposed in refs. 44,45 and demonstrated in ref. 46. Our rf-based protocol offers μeV-level resolution for coupling extraction, which enables tuning the effective dot-to-wire couplings tL and tR. Once we have determined the appropriate voltages for quantum dots 1 and 3, we proceed with interferometry measurements. Section 4 of the Supplementary Information contains further details of the tune-up procedure.

Fermion parity measurement and interpretation

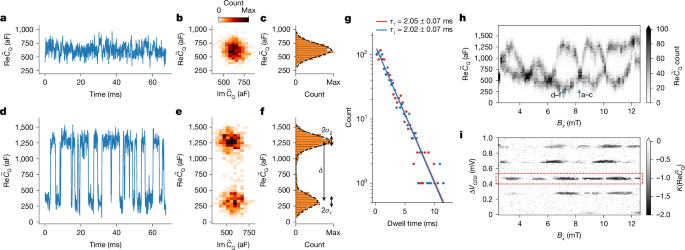

To measure a time record of the fermion parity, we tune up the TQDI and perform a sequence of nearly 1.5 × 104 consecutive measurements of the resonator response, each with an integration time of 4.5 μs, thereby recording a time trace of total length 67 ms. To improve visibility and compare with theoretical predictions, we downsample the time trace by averaging over a 90-μs window. By comparing the measured resonator response with a reference trace (taken with dot 2 in a Coulomb valley), we convert it to a \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) record, which includes a field-dependent shift of CQ that cancels out of ΔCQ (see equation (28) in the Supplementary Information).

We sweep VQD2 to find charge transitions in dot 2 and, because the normal to the plane of the device is only slightly offset (<1°) from the x axis of the magnet, we sweep the x component of the magnetic field Bx in steps of 0.14 mT to study the dependence on Φ. Our Bx sweep range is offset from 0 so that B⊥ (which contains a contribution from Bz) is swept symmetrically around 0. We use the topological gap protocol (TGP)14 to select an in-plane field B∥ and a wire plunger gate voltage VWP1 range (indicated, respectively, in Fig. 1a,c) for our measurements, as discussed in Section 4 of the Supplementary Information. The readout system parameters that we achieve are not strongly dependent on these values. For measurement A1 of device A, the relevant regime is B∥ ≈ 1.8 T and VWP1 ≈ −1.832 V.

For appropriately tuned quantum dot plungers, in particular for VQD2 close to resonance, the measured \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) record exhibits switches between two capacitance values that differ by a ΔCQ(Bx) that oscillates as a function of Bx. At some Bx, there are no visible switches, as in Fig. 3a, so ΔCQ(Bx) vanishes. At generic Bx, there is a clear random telegraph signal (RTS), which is shown in Fig. 3d for the Bx that corresponds to maximal ΔCQ(Bx). From a histogram of all \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) observed within this time trace, we extract an achieved SNR of 5.01 in 90 μs (Fig. 3e,f) or, equivalently, an SNR of 1 in 3.6 μs (see Section 3.3 of the Supplementary Information). As demonstrated in Fig. 3g, the intervals between switches follow an exponential distribution with a characteristic time τRTS ≈ 2 ms. By plotting histograms of the \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) time traces as a function of Bx, as shown in Fig. 3h, we observe a Bx-dependent bimodal distribution of \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) values with peaks separated by ΔCQ(Bx). The oscillation period of ΔCQ(Bx) is 1.9 ± 0.1 mT, which is consistent with the expected flux of h/2e through the interference loop in this device geometry. We interpret the RTS in CQ as originating from switches of the fermion parity in the wire; see Section 7.3 of the Supplementary Information for details.

Measurements in device A (measurement A1) in the (B∥, VWP1) parameter regime identified through the tune-up procedure discussed in the main text and Section 4 of the Supplementary Information; specifically, VWP1 = −1.8314 V and B∥ = 1.8 T. The raw rf signal has been converted to complex \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) by the method described in Section 3.1 of the Supplementary Information. a,d, Time traces at Bx values corresponding to minimal (panel a) and maximal (panel d) values of ΔCQ for a fixed choice of VQD2 close to charge degeneracy. b,e, Histograms of complex \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) for the time trace shown in panels a and d. c,f, Histograms of the real part \({\rm{Re}}{\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) with Gaussian fits for an extraction of the SNR = δ/(σ1 + σ2) = 5.01, the details of which are given in Section 3.3 of the Supplementary Information. g, Histogram of dwell times aggregated over all values of Bx, in which the signal shows bimodality. Fitting to an exponential shows that the up and down dwell times agree to within the standard error on the fits: 2.05 ± 0.07 ms and 2.02 ± 0.07 ms, respectively. h, Histogram of \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) values as a function of Bx, showing clear bimodality that is flux-dependent with period h/2e. The vertical arrows indicate the Bx values at which the time traces in panels a and d were taken. i, Kurtosis in the measured quantum capacitance, \(K(\text{Re}{\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}})\), of dot 2 as a function of Bx (which controls Φ) and ΔVQD2, the change in dot plunger gate voltage from the starting point of the scan (which controls the dot 2 detuning). The dashed red rectangle indicates the ΔVQD2 value at which the data in the other panels were taken.

The visibility and phase of the oscillations vary between successive charge transitions in dot 2. We illustrate this by showing the kurtosis K(CQ) (which detects bimodality; see Section 3.2 of the Supplementary Information) of the \({\widetilde{C}}_{{\rm{Q}}}\) time traces for several different charge transitions in Fig. 3i. A similar difference in the visibility of flux-induced oscillations across different charge transitions was recently observed in a double quantum dot interferometer experiment47. In Section 6 of the Supplementary Information, we discuss oscillations with different periods that are observed at other points in the parameter space of the device.

We support this interpretation by reproducing our results with quantum dynamics simulations that incorporate rf drive power, charge noise and temperature. To build intuition for those simulations, we use an idealized model (see Section 2.2 of the Supplementary Information) subject to the following assumptions (which we will later relax): the wire is in the topological phase and there are no sub-gap states other than the MZMs; the charging energy and level spacing in the dots are much greater than the temperature; dots 1 and 3 are sufficiently detuned that their influence is fully encapsulated in the effective couplings tL and tR to MZMs at the ends of the wire (see Fig. 1a); and the drive frequency and power are both negligible. In this limit, the quantum capacitance as a function of the total fermion parity in the quantum dot–wire system, Z, is given by

$$\begin{array}{l}{C}_{{\rm{Q}}}(Z\,,\phi )\,=\,\frac{2{e}^{2}{\alpha }^{2}| {t}_{{\rm{C}}}(Z\,,\phi ){| }^{2}}{{[{({E}_{{\rm{D}}}+2Z{E}_{{\rm{M}}})}^{2}+4| {t}_{{\rm{C}}}(Z,\phi ){| }^{2}]}^{3/2}}\\ \,\,\,\,\,\times \,\tanh \left(\frac{\sqrt{{({E}_{{\rm{D}}}+2Z{E}_{{\rm{M}}})}^{2}+4| {t}_{{\rm{C}}}(Z\,,\phi ){| }^{2}}}{2{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}\right),\end{array}$$

(1)

in which ED is the detuning from the charge-degeneracy point, α is the lever arm of the plunger gate to the dot, EM is the MZM energy splitting and T is the temperature. The net effective tunnelling that results from the interference between different trajectories from the dot to the MZMs and back, tC(Z, ϕ), is

$$| {t}_{{\rm{C}}}(Z\,,\phi ){| }^{2}=| {t}_{{\rm{L}}}{| }^{2}+| {t}_{{\rm{R}}}{| }^{2}+2Z| {t}_{{\rm{L}}}| | {t}_{{\rm{R}}}| \sin \phi .$$

(2)

Here ϕ is the phase difference between tL and tR, which is controlled by the magnetic flux Φ through the interference loop created by the dot, the wire and the tunnelling paths between them according to ϕ = 2πΦ/Φ0 + ϕ0, in which Φ0 = h/e and ϕ0 is a flux-independent offset. To capture the extent to which CQ can be used to discriminate between Z = ±1, it is convenient to introduce

$$\Delta {C}_{{\rm{Q}}}(\phi )=| {C}_{{\rm{Q}}}(Z=1,\phi )-{C}_{{\rm{Q}}}(Z=-1,\phi )| .$$

(3)

The interferometer must be well balanced tL ≈ tR for ΔCQ to be large according to equation (1). When EM = 0, ΔCQ exhibits maxima along the ED = 0 line, with flux periodicity h/2e.

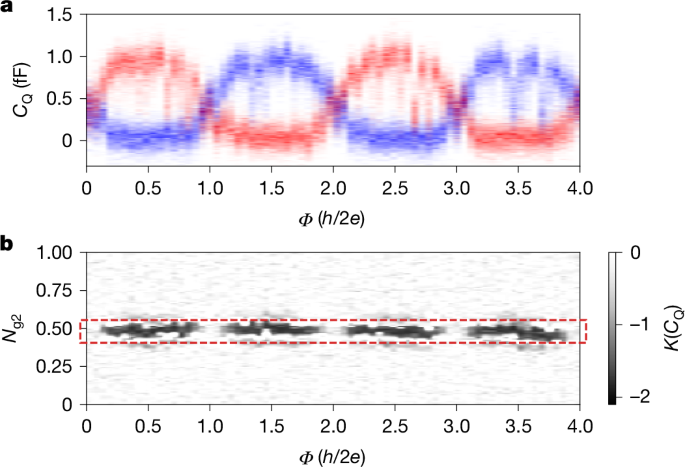

For detailed comparison with experiments, we use the methods discussed in Sections 2.4 and 2.5 of the Supplementary Information to simulate a more complete model of the device and readout chain that includes the full triple-dot system, incoherent coupling to the environment (using parameters inferred from separate measurements; see Sections 9 and 10 of the Supplementary Information) and measurement backaction. Crucially, this approach allows us to incorporate different noise sources in a systematic and quantitative way without any free parameters. The simulated dynamical CQ, defined in Section 2.3 of the Supplementary Information, is shown in Fig. 4. The CQ histograms in Fig. 4a reveal two h/e-periodic branches (one shown in red and the other in blue), associated with the two parities of the coupled system. If the fermion parity Z were perfectly conserved, then the device would remain in one of the two parity eigenstates and the Φ dependence would follow either the blue or the red trace in Fig. 4a. However, Z should fluctuate on a timescale given by the quasiparticle poisoning time τqpp. Hence, in traces over times longer than τqpp, a bimodal distribution of CQ values is expected, that is, both the blue and red traces in Fig. 4a. Consequently, the kurtosis K(CQ) exhibits minima at which ΔCQ is peaked, as shown in Fig. 4b, and time traces taken at these points will exhibit a telegraph signal composed of switches between the values CQ(1, ϕ) and CQ(−1, ϕ). Comparing Fig. 4 with Fig. 3h,i, we find good overall agreement of both the histograms and the kurtosis. We find a maximum ΔCQ(Φ) ≈ 1 fF, which is consistent with our measurements in Fig. 3. This agreement extends to other parameter regimes, such as when the interferometer is poorly balanced or the splitting EM is sizeable, as discussed in Section 6 of the Supplementary Information.

Simulated dynamical CQ as a function of magnetic flux and dot 2 gate offset charge Ng2, including the effects of charge and readout noise, as well as non-zero temperature, drive power and frequency, per the discussion in the text. a, Histogram of the two parity sectors for fixed Ng2 = 0.49. Here we used tm1 = tm2 = 6 μeV, t12 = t23 = 8 μeV, EC1 = 140 μeV, EC2 = 45 μeV, EC3 = 100 μeV, Ng1 = Ng3 = 0.3, T = 50 mK and EM = 0. b, Kurtosis of CQ(t) as a function of Ng2 and flux through the loop. The middle of the dashed red rectangle indicates the Ng2 value used for the linecut in panel a.

A second measurement of device A and a measurement of a second device (device B) give results in qualitative agreement with those of measurement A1, demonstrating the reproducibility of the observed phenomena (Section 5 of the Supplementary Information). We have tested our interpretation by: (1) disconnecting the dots from the wire; (2) measuring at fields of 0.8 T below the region identified by TGP; (3) intentionally injecting quasiparticles into the superconductor and observing the effect on τRTS; and (4) comparing the quasiparticle density measured in a separate test structure with that inferred according to the hypothesis that τqpp = τRTS ≈ 2 ms (Section 7 of the Supplementary Information).

By extending the model introduced above, we have analysed the quasi-MZM scenario discussed in previous works37,38,39,48. We introduce an extra pair of ‘hidden’ Majorana modes that are weakly coupled to each other and to the visible MZMs, which themselves are coupled to quantum dots 1 and 3. Together, the hidden and visible MZMs form a trivial low-energy state at each end of the wire. This scenario can occur in the trivial phase, in which it requires some fine-tuning to make the couplings small. In Section 2.7 of the Supplementary Information, we show that the hidden Majorana modes suppress ΔCQ owing to fast fermion tunnelling between them and the visible MZMs. This effect completely washes out the flux-dependent bimodality unless the coupling between the ‘hidden’ Majorana modes and the visible MZMs is less than 1 neV or the hidden Majorana modes are effectively gapped out, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Discussion and outlook

We have presented dispersive gate-sensing measurements of the quantum capacitance in InAs–Al hybrid devices using a system architecture that can be adapted to other materials platforms49,50. After tuning the nanowire density and in-plane magnetic field into the parameter regime identified by the TGP14 and balancing the interferometer formed by the nanowire and the quantum dots, we observed a flux-dependent bimodal RTS in the quantum capacitance, which we interpret as switches of the parity of a fermionic state in the wire. We have fit these data to a model in which the fermion parity is associated with two MZMs localized at the opposite ends of a 1DTS and find good agreement. These measurements do not, by themselves, determine whether the low-energy states detected by interferometry are topological. However, our data tightly constrain the allowable energy splittings in models of trivial Andreev states.

In conclusion, our findings represent substantial progress towards the realization of a topological qubit based on measurement-only operations. Single-shot fermion parity measurements are a key requirement for a Majorana-based topological quantum computation architecture.

Data availability

The datasets associated with the figures in this paper are available at Zenodo51 (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14804379). Further data from devices A and B demonstrating the functionality of this device architecture for fermion parity measurements (namely, quantum dot charging energies and level spacings, inter-dot couplings, dot–wire couplings and wire plunger gates) are available from the corresponding author on request.

Code availability

The source code that performs the analysis and generates the figures in this paper are available at our public GitHub repository at github.com/microsoft/azure-quantum-parity-readout.

References

Bonderson, P., Freedman, M. & Nayak, C. Measurement-only topological quantum computation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 010501 (2008).

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys.-Usp. 44, 131 (2001).

Lutchyn, R. M., Sau, J. D. & Das Sarma, S. Majorana fermions and a topological phase transition in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 077001 (2010).

Oreg, Y., Refael, G. & von Oppen, F. Helical liquids and Majorana bound states in quantum wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 177002 (2010).

Karzig, T. et al. Scalable designs for quasiparticle-poisoning-protected topological quantum computation with Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 95, 235305 (2017).

Akhmerov, A. R., Nilsson, J. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Electrically detected interferometry of Majorana fermions in a topological insulator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 216404 (2009).

Fu, L. & Kane, C. L. Probing neutral Majorana fermion edge modes with charge transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 216403 (2009).

Fu, L. Electron teleportation via Majorana bound states in a mesoscopic superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 056402 (2010).

Houzet, M., Meyer, J. S., Badiane, D. M. & Glazman, L. I. Dynamics of Majorana states in a topological Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 046401 (2013).

Plugge, S. et al. Roadmap to Majorana surface codes. Phys. Rev. B 94, 174514 (2016).

Vijay, S., Hsieh, T. H. & Fu, L. Majorana fermion surface code for universal quantum computation. Phys. Rev. X 5, 041038 (2015).

Nichele, F. et al. Scaling of Majorana zero-bias conductance peaks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 136803 (2017).

Suominen, H. J. et al. Zero-energy modes from coalescing Andreev states in a two-dimensional semiconductor-superconductor hybrid platform. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 176805 (2017).

Aghaee, M. et al. InAs-Al hybrid devices passing the topological gap protocol. Phys. Rev. B 107, 245423 (2023).

Kitaev, A. Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 303, 2–30 (2003).

Freedman, M. H. P/NP, and the quantum field computer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 98–101 (1998).

ADS MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M. & Das Sarma, S. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 1083–1159 (2008).

Hastings, M. B. & Haah, J. Dynamically generated logical qubits. Quantum 5, 564 (2021).

Paetznick, A. et al. Performance of planar Floquet codes with Majorana-based qubits. PRX Quantum 4, 010310 (2023).

Grans-Samuelsson, L. et al. Improved pairwise measurement-based surface code. Quantum 8, 1429 (2024).

Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M. & Cleland, A. N. Surface codes: towards practical large-scale quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 86, 032324 (2012).

Preskill, J. Quantum computing in the NISQ era and beyond. Quantum 2, 79 (2018).

Gidney, C. & Ekerå, M. How to factor 2048 bit RSA integers in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits. Quantum 5, 433 (2021).

Beverland, M. E. et al. Assessing requirements to scale to practical quantum advantage. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.07629 (2022).

Sau, J. D., Clarke, D. J. & Tewari, S. Controlling non-Abelian statistics of Majorana fermions in semiconductor nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 84, 094505 (2011).

van Heck, B., Akhmerov, A. R., Hassler, F., Burrello, M. & Beenakker, C. W. J. Coulomb-assisted braiding of Majorana fermions in a Josephson junction array. New J. Phys. 14, 035019 (2012).

Fidkowski, L., Lutchyn, R. M., Nayak, C. & Fisher, M. P. A. Majorana zero modes in one-dimensional quantum wires without long-ranged superconducting order. Phys. Rev. B 84, 195436 (2011).

Whiticar, A. M. et al. Coherent transport through a Majorana island in an Aharonov–Bohm interferometer. Nat. Commun. 11, 3212 (2020).

Plugge, S., Rasmussen, A., Egger, R. & Flensberg, K. Majorana box qubits. New J. Phys. 19, 012001 (2017).

Steiner, J. F. & von Oppen, F. Readout of Majorana qubits. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 033255 (2020).

Khindanov, A., Pikulin, D. & Karzig, T. Visibility of noisy quantum dot-based measurements of Majorana qubits. SciPost Phys. 10, 127 (2021).

Janvier, C. et al. Coherent manipulation of Andreev states in superconducting atomic contacts. Science 349, 1199–1202 (2015).

Hays, M. et al. Direct microwave measurement of Andreev-bound-state dynamics in a semiconductor-nanowire Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 047001 (2018).

Hays, M. et al. Coherent manipulation of an Andreev spin qubit. Science 373, 430–433 (2021).

Wesdorp, J. J. et al. Dynamical polarization of the fermion parity in a nanowire Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 117001 (2023).

Elfeky, B. H. et al. Evolution of 4π-periodic supercurrent in the presence of an in-plane magnetic field. ACS Nano 17, 4650–4658 (2023).

Kells, G., Meidan, D. & Brouwer, P. W. Near-zero-energy end states in topologically trivial spin-orbit coupled superconducting nanowires with a smooth confinement. Phys. Rev. B 86, 100503 (2012).

Liu, C.-X., Sau, J. D., Stanescu, T. D. & Das Sarma, S. Andreev bound states versus Majorana bound states in quantum dot-nanowire-superconductor hybrid structures: trivial versus topological zero-bias conductance peaks. Phys. Rev. B 96, 075161 (2017).

Vuik, A., Nijholt, B., Akhmerov, A. R. & Wimmer, M. Reproducing topological properties with quasi-Majorana states. SciPost Phys. 7, 061 (2019).

Valentini, M. et al. Nontopological zero-bias peaks in full-shell nanowires induced by flux-tunable Andreev states. Science 373, 82–88 (2021).

Vijay, S. & Fu, L. Physical implementation of a Majorana fermion surface code for fault-tolerant quantum computation. Phys. Scr. 2016, 014002 (2016).

Vijay, S. & Fu, L. Teleportation-based quantum information processing with Majorana zero modes. Phys. Rev. B 94, 235446 (2016).

Hornibrook, J. M. et al. Frequency multiplexing for readout of spin qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 103108 (2014).

Clarke, D. J. Experimentally accessible topological quality factor for wires with zero energy modes. Phys. Rev. B 96, 201109 (2017).

Prada, E., Aguado, R. & San-Jose, P. Measuring Majorana nonlocality and spin structure with a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 96, 085418 (2017).

Deng, M. T. et al. Majorana bound state in a coupled quantum-dot hybrid-nanowire system. Science 354, 1557–1562 (2016).

Proskoet, C. G. et al. Flux-tunable hybridization in a double quantum dot interferometer. SciPost Phys. 17, 074 (2024).

Prada, E., San-Jose, P. & Aguado, R. Transport spectroscopy of NS nanowire junctions with Majorana fermions. Phys. Rev. B 86, 180503 (2012).

Bonderson, P., Nayak, C., Reilly, D., Young, A. F. & Zaletel, M. Scalable designs for topological quantum computation. U.S. patent 11,751,493 B2 (2023).

ten Haaf, S. L. D. et al. A two-site Kitaev chain in a two-dimensional electron gas. Nature 630, 329–334 (2024).

Microsoft (United States). Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs-Al hybrid devices. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14804379 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank H. Beidenkopf, S. Das Sarma, L. Glazman, B. Halperin, A. Kou, K. Moler, W. Pfaff and M. Rudner for discussions. We thank E. Lee and T. Ingalls for assistance with the figures. We are grateful for the contributions of A. Dokania, A. Efimovskaya, L. Johansson and A. Mullally at an early stage of this project. We have benefited from interactions with P. Accisano, P. Bonderson, J. Borovsky, T. Brown, G. Campbell, S. Chakravarthi, K. Das, N. Dick, R. Gatta, H. Gavranovic, M. Goulding, J. Knoblauch, S. Jablonski, S. Kimes, J. Kuesel, J. Mattinson, A. Moini, T. Noonan, D. O. Fernandez Pons, L. Sanderson, M. P. da Silva, P. Strøm-Hansen, S. Suzuki, M. Turner, R. Yu and A. Zimmerman.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Hao Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Microsoft Azure Quantum., Aghaee, M., Alcaraz Ramirez, A. et al. Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs–Al hybrid devices. Nature 638, 651–655 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08445-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08445-2