Main

Ribose and 2-deoxyribose are key sugar constituents of nucleic acids in terrestrial biology (RNA and DNA), which record genetic information and translate it to form proteins that work as the primary catalyst for most biological reactions. Ribose is regarded as a particularly important molecule for the origin of life because RNA may have been a crucial step in the early evolution of life as gene carriers and enzymes1,2,3. Glucose, a sugar molecule, is a ubiquitous energy source and critical component of catabolic pathways, notably glycolysis, the pentose phosphate pathway and the Entner–Doudoroff pathway. Because glycolysis is the common catabolic pathway for nearly all organisms, including aerobic and anaerobic microorganisms, it is regarded as a primitive catabolic pathway4. Thus, the origins and distributions of these sugars in extraterrestrial materials have been investigated to understand the potential for extraterrestrial habitability and exogenous contributions to the early Earth’s prebiotic organic inventory that led to the emergence of life5,6,7.

Meteorites contain diverse organic compounds, including the building blocks of life, such as amino acids, nucleobases, sugars and related compounds6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Dihydroxyacetone, a triose (three-carbon sugar), was found in the Mighei-type (CM) carbonaceous chondrites Murchison and Murray6. Ribose and other pentoses (five-carbon sugars) were found in Murchison and the Renazzo-type (CR) carbonaceous chondrite NWA 8017. Although the carbon isotope compositions of the ribose and pentoses in Murchison and NWA 801 indicate an extraterrestrial origin7, meteorites experience uncontrolled exposure to the biosphere and terrestrial weathering before collection, and they usually have unknown solar system origin. In addition, because terrestrial organisms can grow on meteorites13, if such organisms selectively use 13C-enriched molecules among many others, the heavy carbon isotopic compositions of sugars and other organic molecules previously measured in meteorites may not be proof of an entirely extraterrestrial source.

The OSIRIS-REx mission delivered 121.6 g of regolith (unconsolidated granular material) collected from Bennu to Earth on 24 September 2023, under carefully controlled conditions14. The samples were curated under high-purity N2 at NASA’s Johnson Space Center15. Early studies showed that Bennu has similar mineralogical and elemental characteristics to Ivuna-type (CI) carbonaceous chondrites; is enriched in carbon and nitrogen compared to most meteorites, but resembles ungrouped carbonaceous chondrites; and experienced extensive aqueous alteration14,16. The Bennu samples analysed to date contain soluble organic compounds, including amino acids, amines, carboxylic acids, aldehydes, nucleobases, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and a diverse mixture of soluble molecules composed of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur17. We took advantage of this pristine asteroidal material to search for extraterrestrial bio-essential sugars.

Detection of Bennu sugars

Using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and GC–tandem MS (GC-MS/MS), we searched for sugars in an acid and water extract of a 603.4-mg aliquot (sample ID OREX-800107-108) of homogenized powder made from crushing an aggregate (unsorted) Bennu sample (OREX-800107-0; Methods, Extended Data Fig. 1). The acid extraction was conducted to avoid potential sugar formation and degradation because these reactions are limited in low pH18,19,20.

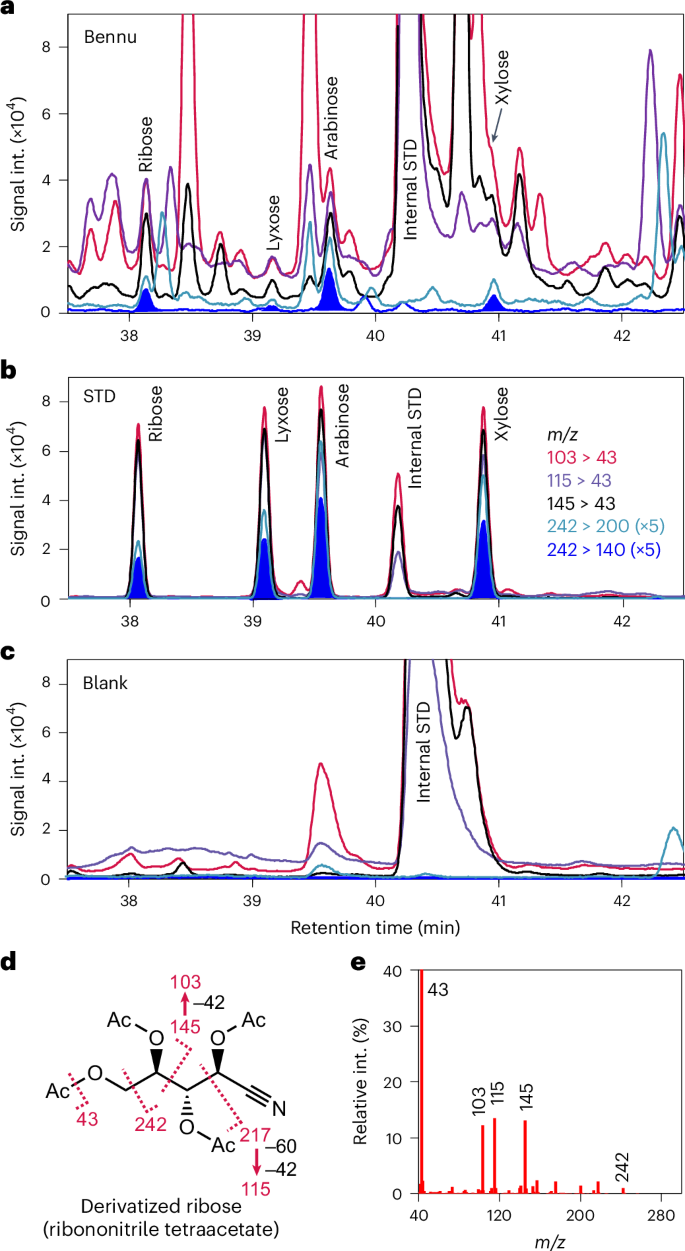

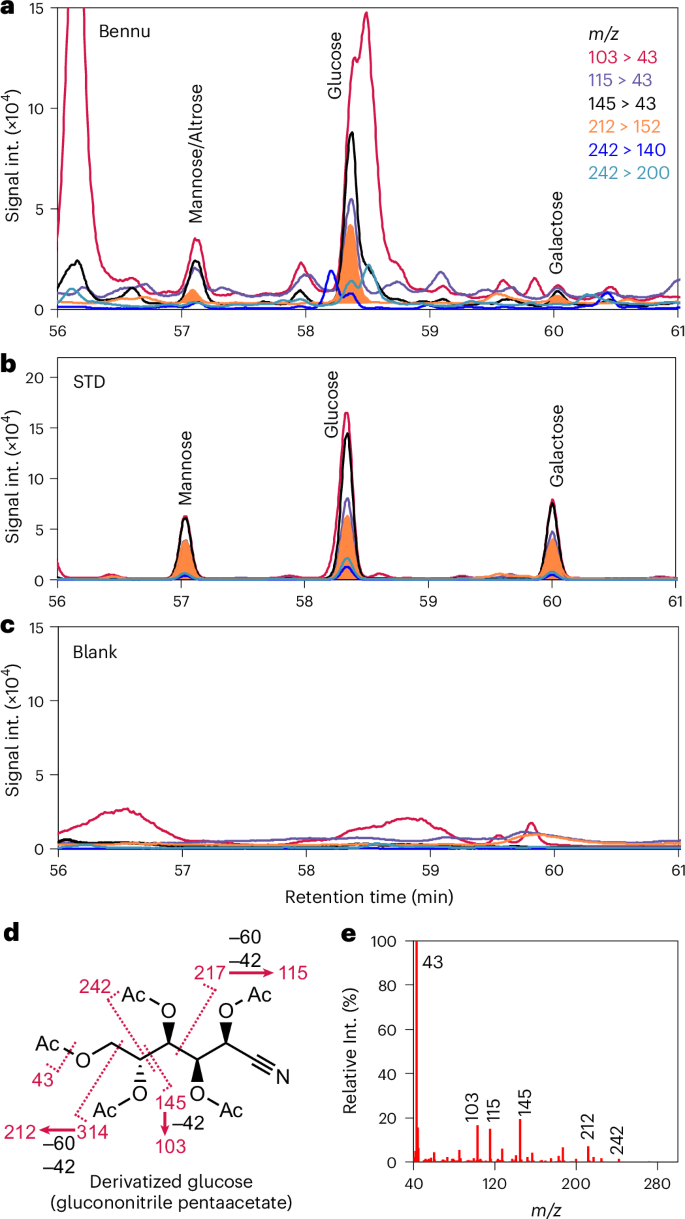

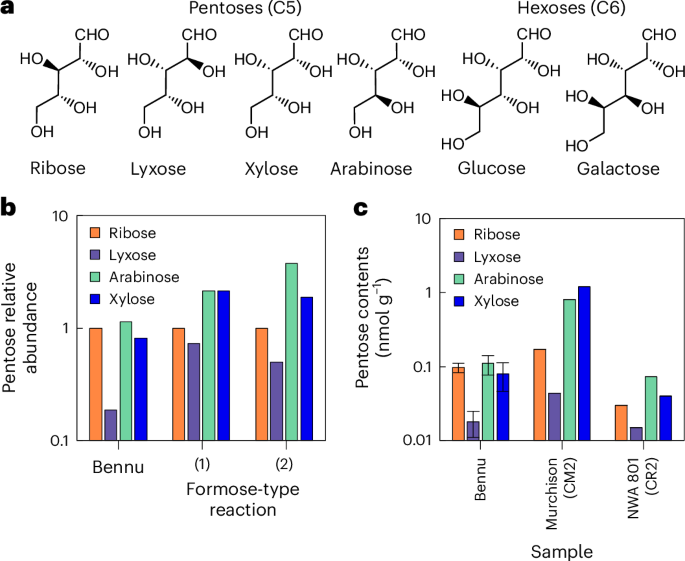

The Bennu extract shows several identical GC-MS/MS peaks to the investigated sugars in all the characteristic fragment masses of the derivatized sugars (Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Figs. 2 and 3). We detected all four aldopentoses—ribose, lyxose, xylose and arabinose—and two aldohexoses, glucose and galactose (Fig. 3a). These identifications were confirmed using a different GC-MS system and a different separation column (Extended Data Figs. 4–6). The abundances of ribose, lyxose, arabinose and xylose were 0.097 ± 0.014, 0.018 ± 0.007, 0.11 ± 0.03 and 0.079 ± 0.033 nmol g−1, respectively (Table 1). Glucose had the highest concentration of the sugars at 0.35 ± 0.05 nmol g−1, whereas galactose was 0.014 ± 0.004 nmol g−1 (Table 1).

a, Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) chromatograms of derivatized pentose fragments in the Bennu extract using a DB-17ms column. b, MRM chromatograms of derivatized pentose standards. c, MRM chromatograms of SiO2 blank. d, Fragmentation of electron ionization (EI) of derivatized ribose (ribononitrile tetraacetate). e, EI fragment spectrum of derivatized ribose. Collision-induced dissociations of the EI fragments are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2. Only the presence of peaks for all five transitions with consistent intensity ratios to standards leads to a confident detection. The additional peaks observed are derived from co-eluting compounds. The co-eluting compounds least influenced the mass transition of m/z 242 to 140. Signal Int., signal intensity; STD, standard.

a, MRM chromatograms of derivatized hexose fragments in the Bennu extract using a DB-17ms column. b, MRM chromatograms of derivatized hexose standards. c, MRM chromatograms of SiO2 blank. d, Fragmentation of EI of derivatized glucose (glucononitrile pentaacetate). e, EI fragment spectrum of derivatized glucose. Collision-induced dissociations of the EI fragments are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3. Only the presence of peaks of all six transitions with consistent intensity ratios to standards leads to a confident detection. The additional peaks observed are derived from co-eluting compounds. The co-eluting compounds least influenced the mass transition of m/z 212 to 152.

a, Identified sugars. b, Relative abundances of pentoses in Bennu and formose-type reaction products. Formose-type reaction product (1) is from formaldehyde and glycolaldehyde in an alkaline solution for 360 min (ref. 7) and (2) is from the reaction of formaldehyde with olivine in a neutral solution for 7 days (FO7)23. c, Abundances of pentoses in the Bennu sample and meteorites7. Data for the Bennu sugars present mean values ± standard deviation in triplicate measurements. The analytical errors for the meteorites were not reported7.

The characteristic fragment masses of hexoses also have peaks indicative of the two other hexoses (mannose and altrose), but these identifications are not definitive. Thus, we do not assert the detection of these sugars and only report their upper limits: mannose, <0.05 nmol g−1; altrose, <0.1 nmol g−1.

Small amounts of sugar alcohols, xylitol (0.005 nmol g−1) and arabitol (0.002 nmol g−1), were also detected (Extended Data Fig. 7). We also searched for other sugars and related compounds, including sugar acids that have previously been reported in meteorites6,21: 2-deoxyribose, threose, erythrose, ribulose, xylulose and branched aldopentoses ((2 R,3S)-2,3,4-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)butanal and (2S,3S)-2,3,4-trihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)butanal) (Table 1). All of them were below the analytical detection limit.

We considered the possibility that contamination by biological organic compounds could have affected our findings. Contamination is a well-documented challenge in meteoritics because even well-preserved and well-handled meteorites were exposed to uncontrolled terrestrial environments before collection. However, the returned samples of Bennu have not experienced such exposure. The chiral amino acids in a recently analysed Bennu aggregate sample were racemic (d = l) or nearly so17, indicating no measurable biological contamination, which would have resulted in a higher abundance of l- relative to d-amino acids. Furthermore, the SiO2 procedural blank (Methods) is free from sugar contamination (Figs. 1 and 2), confirming that the Bennu sample was not contaminated during analytical processing.

The abundances of the biologically important sugars in the Bennu sample (glucose, arabinose, ribose and xylose) might nevertheless suggest the possibility of contamination. However, glucose, arabinose and xylose are relatively stable18,19. The higher thermal stability and lower reactivity of glucose among the aldoses, characterized by a more than one order of magnitude lower reaction rate than that of ribose, is particularly compelling. Thus, the relatively high abundances of these sugars in the Bennu sample are reasonable.

Ribose, though, is not a chemically stable sugar. The reason for its relatively high abundance in the Bennu sample is not immediately apparent, but laboratory simulations of interstellar and asteroidal sugar synthesis22,23 have shown ribose as one of the abundant pentoses, similar to arabinose and xylose. Thus, the observed abundances in the Bennu sample are not inconsistent with abiotic synthesis (Fig. 3b).

The higher abundance of larger sugars compared to smaller sugars, such as hexoses compared to tetroses, is the inverse of the typical distribution of soluble organic compounds, including amino acids, carboxylic acids and amines, in meteorites and other asteroid samples10,17,24,25. However, the higher abundance of larger sugars in Bennu is consistent with a transient state of sugar-forming reactions seen in laboratory experiments of aldehyde reactions, including a reaction simulating asteroidal environments, in which larger sugars form by successively consuming smaller sugars23.

The total abundance of the detected sugars (0.668 nmol g−1) is about 1 mol% of the total abundance of amino acids measured previously in Bennu samples (70 nmol g−1) (ref. 17). Given the low abundances of sugars, high abundances of interfering molecules and sample mass available for this study, stable isotopic and enantiomeric measurements of the sugars were not possible.

We also analysed the pH of hot-water extracts of homogenized Bennu powder (OREX-800107-106) and carbonaceous meteorites (Murchison, Murray and the CI Orgueil) to estimate the parent body pH conditions (Table 2). The pH values we found for Bennu (pH 8.23 ± 0.02) are higher than that of a hot-water extract of Ryugu (pH 3.95–4.19) in which many sulfate and organo-sulfates were contained26. The implied alkaline pH for Bennu’s parent body is consistent with the observation of evaporite minerals16 and the detection of NH3-bearing fluid inclusions27 in other Bennu samples.

Possible formation processes of sugars

Bennu’s large D and 15N enrichments14,17 indicate that its parent body accreted ices and organic matter from a reservoir(s) in the early outer solar system17. Laboratory simulations of ultraviolet and cosmic ray irradiation of an interstellar ice analogue made from methanol and water suggests that sugars, including ribose with larger amounts of smaller sugars such as glyceraldehyde, could have formed in the interstellar medium and the cold outer solar system, before asteroid accretion22,28,29. Formose-type reactions, in which formaldehyde reacts successively to form larger sugars via smaller sugars, have previously been proposed as a possible formation mechanism for sugars in asteroids and in the interstellar medium7,22,23,30. Aldehydes, the source materials of the formose reaction, have been found in interstellar space, comets, many carbonaceous meteorites and Bennu samples17,31,32,33. Aldehydes and small sugars can react with each other to form diverse larger sugars, including those found in Bennu, through the formose reaction in weakly acidic to alkaline fluids, as shown in laboratory simulations7,23,30,34. Veins of potential carbonates in boulders on Bennu observed by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft indicate a history of large-scale fluid activity35, and evaporites in Bennu samples point to past alkaline fluids rich in sodium, magnesium and calcium carbonate16. Calcium and magnesium ions are effective catalysts for sugar synthesis through the formose reaction34,36,37,38. Also, abundant phyllosilicate minerals in the Bennu samples are evidence of microscale ancient aqueous activity14. This geologic history, together with the weakly alkaline pH we measured (8.23 ± 0.02), suggests the plausibility of sugar synthesis through the formose reaction during aqueous processing in Bennu’s parent body.

The formose reaction is followed by several side reactions, including the synthesis of sugar acids and sugar alcohols, and the rearrangements between branched and linear sugars and aldoses and ketoses37,38,39,40. Sugar alcohols and sugar acids have been detected in some carbonaceous meteorites6,21. These compounds are generally formed through disproportionation of sugars via the Cannizzaro and cross-Cannizzaro reactions under highly alkaline solutions. Our detection of small amounts of sugar alcohols in the Bennu sample suggests that these side reactions may have occurred to a limited extent, although they probably did not dominate the prebiotic chemistry. Catalysts for the formose reaction, such as Ca2+, generally direct aldehydes toward sugar synthesis and suppress the Cannizzaro reaction38,39. Bennu’s mineralogy14,35 supports the presence of dissolved divalent cations (that is, Mg and Ca) in aqueous fluids on the parent asteroid.

Experimental studies of the formose reaction under short durations at room temperature have shown that the products contain abundant ketoses and branched sugars34,40, neither of which were detected in the Bennu sample. In contrast, longer-duration reactions at elevated temperatures, particularly with Ca2+ as a catalyst, favour the formation of linear aldopentoses over ketoses and branched sugars34. These findings highlight that the distribution of sugars in the formose reaction is highly sensitive to fluid chemistry and reaction duration38. Thus, further investigation is needed to constrain the specific reaction mechanisms and environmental conditions that led to the formation of asteroidal sugars.

The total abundance of pentoses we detected in the Bennu sample (0.36 nmol g−1) is comparatively low, about 16% of that in the Murchison meteorite (2.2 nmol g−1) (ref. 7) (Table 1 and Fig. 3c). A possible reason for this could be the relatively abundant ammonia in Bennu17: ammonia can react with aldehydes, including sugars, yielding a Schiff base, which could be converted into other molecules such as amino acids, amines and nitrogen heterocycles41,42,43,44,45. However, these compounds are also less abundant in Bennu samples17—about 30–50% of those in Murchison—suggesting additional reasons for the lower abundance of sugars.

The slightly more alkaline pH of the Bennu extract compared with carbonaceous meteorites (Table 2) could be related to Bennu’s ammonia enrichment and might indicate that the reactions between sugars and aldehydes progressed faster in Bennu’s parent asteroid, because alkaline pH substantially promotes these reactions34. Abundant evaporites, phyllosilicates and carbonates in the Bennu samples14,16 record more substantial aqueous processes in the parent asteroid of Bennu than that of Murchison. Thus, the progress of the reactions between sugars and aldehydes is a more probable reason for the lower abundance of sugars in Bennu. Because successive formaldehyde addition to existing small sugars forms new, larger sugars, pentoses and hexoses that existed before the asteroidal aqueous processing were most likely consumed in the reactions. We therefore propose that the detected Bennu sugars were formed by asteroidal processes acting on interstellar materials, rather than having been formed in interstellar environments and surviving the reactive asteroidal processes.

We did not find the DNA sugar, 2-deoxyribose, in the Bennu sample we analysed. 2-Deoxyribose and deoxy sugar derivatives were reported in a laboratory photochemical reaction in methanol-containing ice28 and a laboratory formose reaction23. The 2-deoxyribose has more than two orders of magnitude higher chemical reactivity than sugars detected in the Bennu sample19, yet this molecule has lower sensitivity to thermal decomposition, by a factor of 2.6, than ribose18. Thus, if 2-deoxyribose was formed before asteroid accretion and/or within the parent asteroid, the subsequent aqueous reactions most likely consumed this sugar by the reactions with other molecules. The high reactivity of 2-deoxyribose is also consistent with the limited formation of this sugar in a thermally driven formose reaction23.

Implications for prebiotic chemistry

All five of the canonical nucleobases in DNA and RNA, and phosphate, were previously found in Bennu samples14,17. Our detection of ribose means that all the components of RNA are present in Bennu. The detection of ribose and non-detection of 2-deoxyribose further indicates that ribose may be much more prevalent than 2-deoxyribose in B-type carbonaceous asteroids. The RNA world hypothesis proposes that RNA was the first informational and catalytic polymer that led to the origin of life; later, the system was replaced by DNA and proteins through biological evolution1,2,3. This hypothesis is supported by the chemical and biological functions of RNA in life. The higher availability of ribose over 2-deoxyribose in a primitive asteroid provides additional support.

Hexoses were reported in meteorites in the 1960s46,47. However, these detections were highly uncertain given analytical issues and possible contamination, characterized by the highest abundance of sugars detected in an ordinary chondrite that is now known to contain almost no polar soluble organic compounds47. Hexoses have not been reported in any other extraterrestrial materials. Our confident detection in Bennu of abundant glucose—the hexose molecule that is life’s common energy source—and other hexoses indicates that they were present in the early solar system. Given that the fragments of carbonaceous asteroids appear to be widely distributed in the inner solar system, such asteroids or fragments of asteroids (for example, carbonaceous chondrites), would have provided glucose and other bio-essential sugars to broad areas of the inner solar system, together with nucleobases and protein-building amino acids17,24,25,48. Thus, all three crucial building blocks of life would have reached the prebiotic Earth and other potentially habitable planets.

Methods

Sample extraction and derivatization

The physical homogeneity of the powdered Bennu aliquot (OREX-800107-108; 603.4 mg) was verified by X-ray computed tomography50. The negligible effects of X-rays on sugars during the X-ray computed tomography imaging were previously verified using the Murchison meteorite51. All the extraction and purification steps were conducted in an ISO Class-5 clean bench. Sugars in the powdered Bennu aliquot were extracted into 15 ml of 2% HCl (TAMAPURE-AA10, Tama Chemicals) in a glass test tube with sonication for 30 min under a temperature less than 25 °C. The supernatant of the centrifuged solution was collected (480 × g, 45 min at 10 °C). This process was conducted five times. Sugars in the residue were further extracted with 15 ml water (TAMAPURE-AA, Tama Chemicals) three times. The supernatant was added to the HCl extract. All of the extract was evaporated under a vacuum with a rotary evaporator. Sugars in the residue were extracted into 10 ml of methanol five times (Q-Tof grade, Wako Pure Chemicals), and the methanol was removed under a vacuum with the rotary evaporator. The cation in the residue was removed with 40 ml of a cation exchange resin (AG50-X8 200–400 mesh, Bio-Rad). The resin was washed with 10% NH4OH (ultrapure grade, KANTO Chemical), 1 mol l−1 NaOH (ultrapure grade, KANTO Chemical), 1 mol l−1 HCl (TAMAPURE-AA, Tama Chemicals) and water (TAMAPURE-AA, Tama Chemicals) before the sample load. The sugar fraction was collected by washing the resin with 100 ml water. The resin with cations was further used for nucleobase analysis. The sugar fraction was dried under a vacuum. Ten percent of this fraction was used for nucleobase analysis. The other 90% was combined with an internal standard (2-deoxy-fluoro-glucose) and derivatized into aldonitrile acetate. A similar mass of silica powder from a thermally treated (500 °C overnight) synthetic SiO2 (600 mg; Isomass Analytics, 0.85–1.7 mm diameter chips) was used as the procedural blank material to assess the potential for contamination of the Bennu sample during sample powdering, extraction, derivatization and analysis. We used a well-characterized silica material as a control rather than a phyllosilicate mineral (such as serpentine found in Bennu) because SiO2 is stable at the 500 °C bakeout temperature used. Moreover, the synthetic SiO2 used is distinct from any minerals in Bennu, therefore any cross-contamination of particles that occurred during sample processing (note that the SiO2 and Bennu aggregate material were crushed in different quartz mortar and pestle sets on separate days to minimize this possibility) could be readily identified in the Bennu sample and the SiO2 control. The derivatization was reported elsewhere7. All sample handling was conducted with glassware thermally cleaned at 500 °C in air for 6 h before use.

Identification and quantification

The derivatized sample was dissolved in 100 μl of 50% hexane and 50% ethyl acetate. The identification of sugars was conducted with GC-MS/MS (GCMS-TQ8040, SHIMADZU) and GC-MS (5977B, Agilent) using two different separation columns (DB-17 ms and DB-5 ms, Agilent). For the GC-MS/MS, 5 μl of the sample was injected into the inlet at 250 °C with splitless mode. The temperatures of the transfer line and the ion source were 250 and 200 °C, respectively. For the GC-MS, 5 μl of the sample was injected into the inlet (CIS4, GERSTEL) with solvent vent mode of Programmable Temperature Vaporization. The Programmable Temperature Vaporization inlet was initially at 10 °C for 1 min, followed by the ramp up at 12 °C s−1 to 300 °C and kept for 10 min. The temperatures of the transfer line, ion source and quadrupole were 300, 230 and 150 °C, respectively. The separation with the DB-17ms column (60-m length, 0.25-mm inner diameter, 0.25-μm film thick) was conducted with a He column flow rate of 0.8 ml min−1. The column oven, initially at 50 °C for 2 min, was ramped up to 122 °C at the rate of 15 °C min−1, kept for 5 min, ramped up to 160 °C at the rate of 5 °C min−1, ramped up to 195 °C at the rate of 3 °C/ min−1, kept for 15 min and finally ramped up to 270 °C at the rate of 1.5 °C min−1. The separation with the DB-5 ms column (30-m length, 0.25-mm inner diameter, 0.25-μm film thick) was conducted with a total He flow rate of 18.2 ml min−1 and a column flow rate of 1.2 ml min−1. The column oven, initially at 50 °C, was ramped up to 100 °C at the rate of 10 °C min−1, 170 °C at the rate of 3 °C min−1, 220 °C at the rate of 1.5 °C min−1 and 300 °C for 10 min at the rate of 40 °C min−1. The retention time was calibrated with the internal standard. The quantification of the detected sugars was conducted using the same external standard and an internal standard (2-deoxy-fluoro-glucose). All these sugars were absent in the procedural blank (Figs. 1 and 2 and Extended Data Figs. 4–6).

We investigated the mass chromatograms of characteristic fragment ions of target sugars at the calibrated retention times corresponding to the sugars. Several fragment chromatograms are disturbed by co-eluting compounds. We identified the compounds based on the following criteria: (1) each of the five key fragments has a peak at the same retention times corresponding to pentose standards and each of the six fragments for the hexose standards, (2) the relative abundance of the fragments are also consistent with the standard, considering the interference by partly overlapping near peaks and background increase for specific chromatograms. When one of the chromatograms has a retention time that differs by more than 0.05 min, we exclude the identification. The abundance was calculated based on a peak area among the key fragment multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) chromatograms (that is, mass transitions of m/z 242 > 140 for pentoses and m/z 121 > 152 for hexoses. These fragment chromatograms have not been interfered with by co-eluting peaks. The peak identification was further confirmed by the analysis of a spiked sample with standards. The spiking experiment was conducted using the original Bennu sample and standard, approximately ten months after the extraction and derivatization. The sample and the standard were dried and stored at −80 °C until the second analysis. Although the peak intensity was reduced to approximately 50% from the original analysis, peaks still have sufficient intensities (Extended Data Fig. 8).

pH Measurement

We performed the hot-water extraction based on a previously published method (105 °C, 20 h) (ref. 24). Then, we conducted small-scale pH measurements ( <7 μl) of the hot-water extract (49.7 mg of OREX-800107-106) at 21.5 °C (within ± 0.1 °C in ambient atmosphere) by using a LAQUA F-73 instrument (HORIBA Advanced Techno Co. Ltd.) with a pH electrode (model 0040-10D), as reported in a previous study26. A three-point calibration was performed with phosphate standard solutions of pH 4.01 and 6.86 (certificate) and a tetraborate standard solution of pH 9.18 (Kanto Chemical Co. Inc.). All pH measurement scans were statically performed at least 200 times for each measurement (~1 Hz) (Extended Data Fig. 9). We also represent the pH measurement of the procedure blank with 49.1 mg of SiO2. We also measured the pH profiles for similar extracts of representative carbonaceous meteorites (that is, Murchison, Murray and Orgueil) as references. The Murchison extract was prepared by ref. 24, and the extracts of Murray and Orgueil were prepared by ref. 49.

Data availability

The instrument data products underlying the findings of this work are available via astromat.org at the DOIs listed in Supplementary Table 1.

References

Joyce, G. F. RNA evolution and the origins of life. Nature 338, 217–224 (1989).

Dworkin, J. P., Lazcano, A. & Miller, S. L. The roads to and from the RNA world. J. Theor. Biol. 222, 127–134 (2003).

Orgel, L. E. Prebiotic chemistry and the origin of the RNA world. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39, 99–123 (2004).

Chandel, N. S. Glycolysis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 13, a040535 (2021).

Hollis, J. M., Lovas, F. J. & Jewell, P. R. Interstellar glycolaldehyde: the first sugar. Astrophys. J. Lett. 540, L107 (2000).

Cooper, G. et al. Carbonaceous meteorites as a source of sugar-related organic compounds for the early Earth. Nature 414, 879–883 (2001).

Furukawa, Y. et al. Extraterrestrial ribose and other sugars in primitive meteorites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 24440–24445 (2019).

Martins, Z. et al. Extraterrestrial nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 270, 130–136 (2008).

Callahan, M. P. et al. Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13995–13998 (2011).

Glavin, D. P., Callahan, M. P., Dworkin, J. P. & Elsila, J. E. The effects of parent body processes on amino acids in carbonaceous chondrites. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 45, 1948–1972 (2011).

Oba, Y. et al. Identifying the wide diversity of extraterrestrial purine and pyrimidine nucleobases in carbonaceous meteorites. Nat. Commun. 13, 2008 (2022).

Koga, T., Takano, Y., Oba, Y., Naraoka, H. & Ohkouchi, N. Abundant extraterrestrial purine nucleobases in the Murchison meteorite: implications for a unified mechanism for purine synthesis in carbonaceous chondrite parent bodies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 365, 253–265 (2024).

Waajen, A. C., Lima, C., Goodacre, R. & Cockell, C. S. Life on Earth can grow on extraterrestrial organic carbon. Sci. Rep. 14, 3691 (2024).

Lauretta, D. S. et al. Asteroid (101955) Bennu in the laboratory: properties of the sample collected by OSIRIS-REx. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 2453–2486 (2024).

Righter, K. et al. Curation planning and facilities for asteroid Bennu samples returned by the OSIRIS-REx mission. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 58, 572–590 (2023).

McCoy, T. J. et al. An evaporite sequence from ancient brine recorded in Bennu samples. Nature 637, 1072–1077 (2025).

Glavin, D. P. et al. Abundant ammonia and nitrogen-rich soluble organic matter in samples from asteroid (101955) Bennu. Nat. Astron. 9, 199–210 (2025).

Larralde, R., Robertson, M. P. & Miller, S. L. Rates of decomposition of ribose and other sugars: implications for chemical evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 8158–8160 (1995).

Dworkin, J. P. & Miller, S. L. A kinetic estimate of the free aldehyde content of aldoses. Carbohydr. Res. 329, 359–365 (2000).

Yi, R. et al. Erythrose and threose: carbonyl migrations, epimerizations, aldol, and oxidative fragmentation reactions under plausible prebiotic conditions. Chem. A Eur. J. 29, e202202816 (2023).

Cooper, G. & Rios, A. C. Enantiomer excesses of rare and common sugar derivatives in carbonaceous meteorites. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E3322–E3331 (2016).

Meinert, C. et al. Ribose and related sugars from ultraviolet irradiation of interstellar ice analogs. Science 352, 208–212 (2016).

Vinogradoff, V. et al. Olivine-catalyzed glycolaldehyde and sugar synthesis under aqueous conditions: application to prebiotic chemistry. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 626, 118558 (2024).

Naraoka, H. et al. Soluble organic molecules in samples of the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Science 379, eabn9033 (2023).

Parker, E. T. et al. Extraterrestrial amino acids and amines identified in asteroid Ryugu samples returned by the Hayabusa2 mission. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 347, 42–57 (2023).

Yoshimura, T. et al. Chemical evolution of primordial salts and organic sulfur molecules in the asteroid 162173 Ryugu. Nat. Commun. 14, 5284 (2023).

Prince, B. S. et al. Natural liquid cells: nanoscale fluid inclusions in asteroid samples. Microsc. Microanal. 31, ozaf048.751 (2025).

Nuevo, M., Cooper, G. & Sandford, S. A. Deoxyribose and deoxysugar derivatives from photoprocessed astrophysical ice analogues and comparison to meteorites. Nat. Commun. 9, 10 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Ionizing radiation exposure on Arrokoth shapes a sugar world. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2320215121 (2024).

Abe, S., Yoda, I., Kobayashi, K. & Kebukawa, Y. Gamma-ray-induced synthesis of sugars in meteorite parent bodies. ACS Earth Space Chem. 8, 1737–1744 (2024).

Milam, S. N. et al. Formaldehyde in comets C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp), C/2002 T7 (LINEAR), and C/2001 Q4 (NEAT): investigating the cometary origin of H2CO. Astrophys. J. 649, 1169–1177 (2006).

Jes, K. J. et al. Detection of the simplest sugar, glycolaldehyde, in a solar-type protostar with ALMA. Astrophys. J. Lett. 757, L4 (2012).

Aponte, J. C., Whitaker, D., Powner, M. W., Elsila, J. E. & Dworkin, J. P. Analyses of aliphatic aldehydes and ketones in carbonaceous chondrites. ACS Earth Space Chem. 3, 463–472 (2019).

Ono, C. et al. Abiotic ribose synthesis under aqueous environments with various chemical conditions. Astrobiology 24, 489–497 (2024).

Kaplan, H. H. et al. Bright carbonate veins on asteroid (101955) Bennu: implications for aqueous alteration history. Science 370, eabc3557 (2020).

Shigemasa, Y., Fujitani, T., Sakazawa, C. & Matsuura, T. Formose reactions 3. Evaluation of various factors affecting formose reaction. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 50, 1527–1531 (1977).

Kim, H.-J. et al. Synthesis of carbohydrates in mineral-guided prebiotic cycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 9457–9468 (2011).

Robinson, W. E., Daines, E., van Duppen, P., de Jong, T. & Huck, W. T. S. Environmental conditions drive self-organization of reaction pathways in a prebiotic reaction network. Nat. Chem. 14, 623–631 (2022).

Tambawala, H. & Weiss, A. H. Homogeneously catalyzed formaldehyde condensation to carbohydrates: II. instabilities and Cannizzaro effects. J. Catal. 26, 388–400 (1972).

Sutton, S. M., Pulletikurti, S., Lin, H., Krishnamurthy, R. & Liotta, C. L. Abiotic aldol reactions of formaldehyde with ketoses and aldoses—implications for the prebiotic synthesis of sugars by the formose reaction. Preprint at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5055161 (2024).

Koga, T. & Naraoka, H. Synthesis of amino acids from aldehydes and ammonia: implications for organic reactions in carbonaceous chondrite parent bodies. ACS Earth Space Chem. 6, 1311–1320 (2022).

Kebukawa, Y., Chan, Q. H. S., Tachibana, S., Kobayashi, K. & Zolensky, M. E. One-pot synthesis of amino acid precursors with insoluble organic matter in planetesimals with aqueous activity. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602093 (2017).

Vinogradoff, V. et al. Impact of phyllosilicates on amino acid formation under asteroidal conditions. ACS Earth Space Chem. 4, 1398–1407 (2020).

Furukawa, Y., Iwasa, Y. & Chikaraishi, Y. Synthesis of 13C-enriched amino acids with 13C-depleted insoluble organic matter in a formose-type reaction in the early solar system. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd3575 (2021).

Hirakawa, Y., Okamura, H., Nagatsugi, F., Kakegawa, T. & Furukawa, Y. One-pot synthesis of non-canonical ribonucleosides and their precursors from aldehydes and ammonia under prebiotic Earth conditions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 389, 239–248 (2025).

Degens, E. T. & Bajor, M. Amino acids and sugars in the bruderheim and Murray meteorite. Naturwissenschaften 49, 605–606 (1962).

Kaplan, I. R., Degens, E. T. & Reuter, J. H. Organic compounds in stony meteorites. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 27, 805–834 (1963).

Oba, Y. et al. Uracil in the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Nat. Commun. 14, 1292 (2023).

Takano, Y. et al. Primordial aqueous alteration recorded in water-soluble organic molecules from the carbonaceous asteroid (162173) Ryugu. Nat. Commun. 15, 5708 (2024).

Glavin, D. P. et al. The homogenization and sub-division of a large aggregate sample from asteroid Bennu for coordinated analyses. In 56th Lunar and Planetary Science 1079 (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2025).

Glavin, D. P. et al. Investigating the impact of X-ray computed tomography imaging on soluble organic matter in the Murchison meteorite: implications for Bennu sample analyses. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 59, 105–133 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by NASA under award NNH09ZDA007O and contract NNM10AA11C issued through the New Frontiers Program. We acknowledge the entire OSIRIS-REx team for enabling the return and analysis of samples from asteroid Bennu. We thank the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) for the support of our analyses. This work is supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) under KAKENHI 18H03728 and 22H00165 (Y.F.). We thank the members of the Central Laboratory of Teikyo University for their support in performing the GC-MS/MS analysis. The small-scale pH measurement was conducted by the official collaboration agreement through the joint research project with JAMSTEC (Y.T.), HORIBA Advanced Techno Co. Ltd. (T.Y.) and HORIBA Techno Service Co. Ltd. (S.T.). We thank K. Kuwamoto and A. Hamada (HORIBA Advanced Techno) for the technical support of this measurement. The method development was partly supported by JSPS under KAKENHI 21KK0062 (Y.T.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Claude Geffroy-Rodier, Cornelia Meinert and Christian Potiszil for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alison Hunt, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 2 Collision-induced dissociation (CID) ions from characteristic EI fragments of standard ribononitrile acetate in GC-MS/MS.

a, CID spectrum of the m/z 115 ion. b, CID spectrum of the m/z 145 ion. c, CID spectrum of the m/z 103 ion. d, EI spectrum of ribononitrile acetate. e, CID spectrum of the m/z 242 ion at a lower collision energy. f, CID spectrum of the m/z 242 ion at a higher collision energy. Precursor ions are shown in bold black, and the product ions measured for MRM are shown in bold red. CE: collision energy (Volts). Other aldopentoses produce identical EI and CID ions.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CID of characteristic electron ionization (EI) fragments of standard glucononitrile acetate in GC-MS/MS.

a, CID spectrum of the m/z 115 ion. b, CID spectrum of the m/z 145 ion. c, CID spectrum of the m/z 103 ion. d, EI spectrum of glucononitrile acetate. e, CID spectrum of the m/z 212 ion. f, CID spectrum of the m/z 242 ion at a lower collision energy. g, CID spectrum of the m/z 242 ion at a higher collision energy. Precursor ions are shown in bold black, and the product ions measured for MRM are shown in bold red. CE: collision energy (Volts). Other aldohexoses produce identical EI and CID ions.

Extended Data Fig. 4 GC-MS/MS analysis of hexoses in Bennu (sample OREX-800107-108) with DB-5ms column.

a, Mass chromatograms of the Bennu sample. b, Mass chromatograms of hexose standards. c, Mass chromatograms of SiO2 blank (procedural blank).

Extended Data Fig. 5 GC-MS analysis of pentoses in Bennu (sample OREX-800107-108) with DB-17ms column.

a, Mass chromatograms of the Bennu sample. b, Mass chromatograms of pentose standards. c, Mass chromatograms of SiO2 blank (procedural blank).

Extended Data Fig. 6 GC-MS analysis of hexoses in Bennu (sample OREX-800107-108) with DB-17ms column.

a, Mass chromatograms of the Bennu sample. b, Mass chromatograms of hexose standards. c, Mass chromatograms of SiO2 blank (procedural blank).

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Furukawa, Y., Sunami, S., Takano, Y. et al. Bio-essential sugars in samples from asteroid Bennu. Nat. Geosci. (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01838-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01838-6