Introduction

Sleep is a fundamental and evolutionarily conserved behavioral state prevalent across the animal kingdom, ranging from cnidarians to insects and mammals, suggesting that sleep is a Cambrian metazoan adaptation1,2,3,4,5,6. Sleep deprivation (SD) and disturbances are associated with increased risks for health decline in bilaterian animals7,8. The roles of sleep range from cellular repair and energy restoration to synaptic plasticity9,10,11,12. Nevertheless, the evolution of sleep came with major fitness compromises, such as reduced awareness of the environment and vulnerability to predation, and the fundamental conserved cellular functions of sleep remain elusive1,2,13.

Sleep is defined by behavioral criteria and neuronal activity patterns. In most non-mammalian animals, sleep is characterized solely by distinct behavioral criteria, including consolidated periods of behavioral immobility accompanied by an increased arousal threshold in response to external stimuli and species-specific postures1,2,14,15. Sleep is regulated by the circadian process, which determines sleep timing, and by the homeostatic process, which compensates for SD. The presence of sleep and these regulatory processes in basal and derived nocturnal and diurnal species suggests a common evolutionary origin of sleep regulation16,17.

Sleep plays a critical role in the maintenance of genomic integrity: it reduces DNA damage, which accumulates during wakefulness in neurons of flies, fish, and mice18,19,20,21. The causes of DNA damage are diverse and include the solar ultraviolet (UV) radiation, the activity of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the inadvertent action of nuclear enzymes, and neuronal activity20,22,23. The non-dividing and irreplaceable mature excitable neurons may be particularly vulnerable to sleep loss. This cell type evolutionarily emerged in basal metazoans24 and may require sleep to facilitate cellular maintenance. Indeed, sleep-like behavior has recently been observed in two diurnal cnidarians, the upside-down jellyfish Cassiopea and Hydra vulgaris (H. vulgaris)3,4, suggesting that the development of simple nerve nets in cnidarians25,26 coincided with the emergence of sleep.

Cnidarians represent one of the most ancient animal lineages possessing neurons, which extend neurites throughout the endodermal and ectodermal layers, and contain conserved neurotransmitters and neuropeptides27,28. The jellyfish Cassiopea, which lives in obligate symbiosis with photosynthetic dinoflagellates, exhibits rhythmic daily activity that peaks during the day4. In contrast, the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis (N. vectensis), which lacks symbiotic eukaryotes, is considered nocturnal29,30. However, sleep architecture has not been empirically defined in Cassiopea, and sleep has not been characterized in N. vectensis. Thus, the mechanisms that drove the evolution of sleep in these model animals are unknown.

To dissect the origin of animal sleep and its core cellular drivers, we defined and analyzed sleep architecture in Cassiopea andromeda (C. andromeda) and N. vectensis. We found that the light/dark cycle and homeostatic pressure are the primary regulators of sleep in the diurnal C. andromeda, whereas the circadian clock and homeostatic drive are the predominant regulators of sleep in the crepuscular (active at dusk) N. vectensis. Notably, the results demonstrated that the capacity of sleep to relieve neuronal DNA damage is an ancestral trait shared by both symbiotic diurnal and non-symbiotic crepuscular cnidarians. We suggest that sleep may have evolved to enable consolidated periods of neural maintenance.

Results

Characterization of sleep in C. andromeda under controlled conditions and in their natural habitat

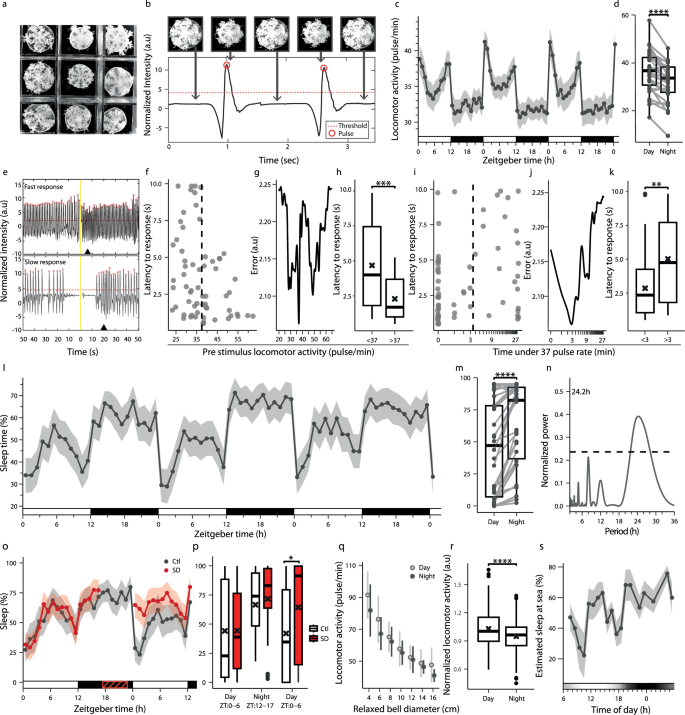

In Cassiopea, a sleep-like state has been characterized by monitoring the rate of pulsation activity of the jellyfish umbrella, which reduces during the night4. To quantify sleep, it is essential to determine the threshold of the pulsation frequency, which can differentiate sleep from wake behavior. An infrared (IR) camera was used to track the simultaneous behavior of multiple C. andromeda during the day and night (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Movie 1). Pulsation events were determined by monitoring the changes in pixel intensity, which reflected expansion and contraction of the C. andromeda bell diameter (Fig. 1b). Consistent with its diurnal nature, locomotor activity consistently reduced during the night in C. andromeda under 12 h light:12 h dark (LD) conditions with a mean pulsation rate of 36.4 ± 1.6 and 31.9 ± 1.4 pulses/min during the day and night, respectively (mean ± SEM; Fig. 1c, d). The constant pulsing behavior31 precluded the use of quiescence to define sleep in C. andromeda. To identify the arousal threshold distinguishing sleep from wake in C. andromeda, we applied a brief light stimulus at night and measured the response latency (Fig. 1e). A threshold-based optimization algorithm was used to determine the optimal behavioral parameters to distinguish between slow and fast responses (Fig. 1g, j). We found that C. andromeda, which pulsed fewer than 37 times per minute (Fig. 1f–h) for more than 3 min (Fig. 1i–k) were slower to respond to the stimulus. Thus, this threshold was used to characterize sleep in C. andromeda. Applying this criterion revealed that the average sleep time increased during the night (63.7%) compared to the day (45.3%) under LD in C. andromeda (Fig. 1l, m). Notably, similar to findings in primates and flies32,33, a midday nap was also observed in C. andromeda (Fig. 1l). The daily average sleep time rhythm was 24.2 h (Fig. 1n). However, rhythmic locomotor activity was abolished under constant darkness (DD) and robustly dampened under constant light (LL) conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d). Moreover, under forced desynchrony conditions (6 h L:6 h D:6 h L:6 h D, LDLD), the animals showed a 12.1 h rhythm of locomotor activity (Supplementary Fig. 1e–g). These findings showed that sleep is primarily driven by the light/dark cycle in C. andromeda. To determine whether sleep in C. andromeda is regulated by a homeostatic process, we sleep-deprived the animals for 6 h (ZT17-ZT23) using computer-controlled alternating repeated water turbulence at night (Supplementary Movie 2). Following SD, C. andromeda displayed sleep rebound, i.e., sleep-deprived animals slept 1.5-fold more than control animals during the day (Fig. 1o, p). In contrast, SD during the active period (ZT5-11) did not induce sleep rebound (Supplementary Fig. 1k, l). These findings show that sleep is regulated by light and homeostatic drive in the diurnal symbiotic C. andromeda.

a Behavioral recording setup. b Pulsations detected from normalized pixel-intensity change. A pulse event (red circle) is defined when the signal crosses the threshold (red dashed line). c Rhythmic pulsation activity over 72 h under LD. d Average pulsation rate under LD (n = 30; ****p < 0.0001). e Examples of fast (top) and slow (bottom) behavioral responses to light stimulation (yellow line). Black triangles mark response to stimulus. f Response latencies versus pre-stimulus pulsation activity. The vertical dashed line (determined from g) separates two distinct behavioral responses. g Classification error across pulsation rates. The minimum defines the optimal threshold (37 pulses/min) separating fast and slow responses. h Average latency in animals above vs. below this threshold (n = 27; ***p < 0.001). i Response latencies plotted against the time spent below 37 pulses/min before stimulus onset. The vertical dashed line (determined from j) separates two distinct behavioral responses. j Classification error across durations spent below 37 pulses/min. The minimum defines the optimal threshold (3 min) separating fast and slow responses. k Average latency in animals below vs. above the 3 min (n = 27; **p < 0.01). l Percent sleep over 72 h under LD. m Average sleep time under LD (n = 30; ****p < 0.0001). n LSP-based periodicity detection of the average sleep time in (l). o Sleep percentages in Ctl (n = 14) and SD (n = 18) animals under LD. p Average sleep percentage for Ctl and SD during day and night pre-SD and day post-SD (Ctl: n = 14, SD: n = 18; *p < 0.05). q Locomotor activity as a function of bell diameter in wild Cassiopea at Key Largo, FL (n = 662; ρ = −0.75, ****p < 0.0001, Spearman). r Average normalized activity per bell diameter group in day/night (****p < 0.0001). s Model-based prediction of 24 h sleep duration in wild Cassiopea. The horizontal grayscale bar represents gradual light changes during the field experiment. Boxplots show median (center line), interquartile range (box), and minima/maxima (whiskers); individual data connected in (d, m); mean (black cross) in (h, k, p, r). Data in (c, l, o, s) are presented as mean ± SEM. White, black, and red horizontal lines represent periods of light, dark, and SD. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (one-tailed) for (d, m). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (one-tailed) for (h, k, r). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (two-tailed) for (p). LSP periodicity detection with p < 0.01 (n).

To generalize the sleep criteria found in the laboratory to Cassiopea’s natural habitat, we monitored the pulsation behavior of wild animals (Supplementary Fig. 1 m) during day and night ( ~ 15 h L: ~9 h D) in shallow water adjacent to the seashore of Key Largo, FL. The findings revealed a strong negative association between the size of Cassiopea and their pulsation rate (Fig. 1q). We therefore normalized the average activity according to the size of each group and showed elevated activity during the day at the sea (Fig. 1r and Supplementary Fig. 1n). Notably, the pulsation threshold used to detect sleep under controlled laboratory conditions (37 pulses/min, Fig. 1f–h) closely matched the average daytime pulse rate observed in the lab (36.4 pulses/min, Fig. 1d). Given this similarity, we approximated the sleep threshold in the field by the average daytime pulse rate, adjusted according to the bell diameter, as a proxy to differentiate sleeping and awake animals. Utilizing this model, we found that the sleep architecture of Cassiopea is similar in the laboratory and the sea. In their natural habitat, the animals primarily sleep at night and nap during midday (Fig. 1s). These results enable the quantification of sleep in various sizes of Cassiopea living in the laboratory and in their natural habitat at sea.

Circadian and homeostatic control of sleep in the crepuscular N. vectensis

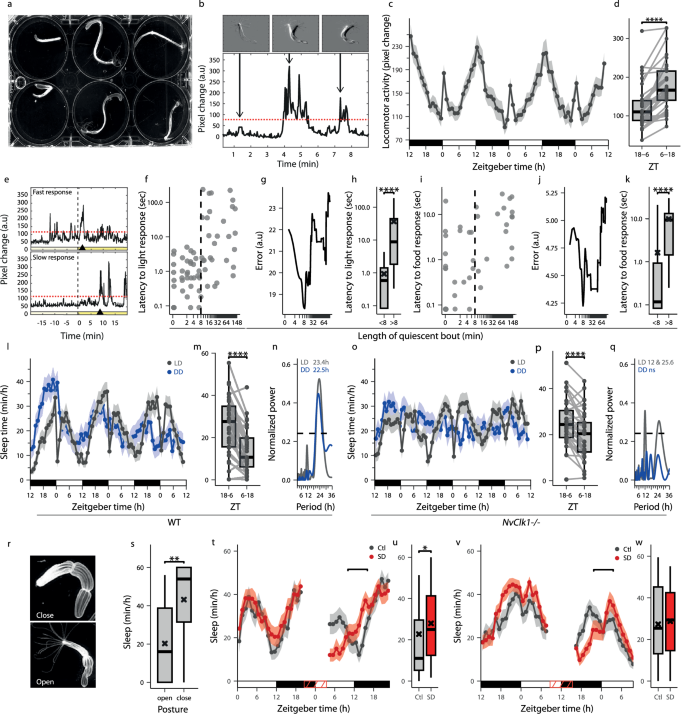

Although rhythmic locomotor activity has been described in N. vectensis29,30,34, sleep was not characterized in sea anemones, including N. vectensis. To detect the state of sleep, we used an IR camera and monitored the behavior of 18 N. vectensis placed individually in three 6-well plate arenas (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Movie 3). We quantified the levels of movement by calculating pixel change above a quiescence threshold, which was set based on MgCl2-paralyzed animals (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). We analyzed 6 h bins (Supplementary Fig. 4) but chose 12 h windows (ZT18-6 and ZT6-18) because they encompass the full crepuscular (i.e., active at dusk) behavioral pattern and align with the 12 h light/dark periods used for C. andromeda (Fig. 1m), facilitating cross-species statistics. In contrast to C. andromeda, under LD, N. vectensis showed rhythmic locomotor activity (Fig. 2c), which increased between ZT6-ZT18 and decreased between ZT18-ZT6 (Fig. 2d). These results indicate that N. vectensis is a crepuscular animal. Notably, the exposure to a sudden artificial dark-to-light transition transiently induced locomotor activity (ZT0-2, Fig. 2c). This robust response to light was used as a stimulus to identify increased arousal threshold in sleeping animals. During daytime (ZT2), N. vectensis was exposed to various light intensities and showed a negative correlation between the light intensity and response latency (Fig. 2e and Supplementary Fig. 2f–k). Using the intermediate-intensity light stimulus and optimization algorithm (Fig. 2g), we found a slower response in N. vectensis individuals that were quiescent for more than 8 min prior to the light stimulus (Fig. 2f–h). To validate this arousal threshold, we tested the response to an additional sensory stimulus, i.e., a food cue. Similar to the response to light (Fig. 2f-h), quiescence lasting at least 8 min resulted in a slower response and could differentiate sleep from quiet wakefulness (Fig. 2i–k). Thus, we defined sleep in N. vectensis as a quiescence state of at least 8 min, which is associated with reversible behavior and increased arousal threshold.

a Behavioral recording setup. b Normalized pixel change was used to quantify movement. Red dotted line indicates the movement threshold. Top images and arrows illustrate pixel change below (left) and above (center, right) the threshold. c Rhythmic locomotor activity during 72 h under LD. d Average locomotor activity during rest (ZT18-6) and active (ZT6-18) periods (n = 33; ****p < 0.0001). e Examples of fast (top) and slow (bottom) responses to light stimulation (yellow line). f Response latency versus quiescent bout duration before light stimulation. The dashed vertical line (determined from g) separates two behavioral responses. g Classification error across quiescence durations. The minimum defines the optimal threshold (8 min) separating fast and slow responses. h Average response latency for animals quiescent less vs. more than 8 min before stimulation (n = 72; ****p < 0.0001). i Response latency versus quiescent bout duration before food stimulation. The dashed vertical line (determined from j) separates two behavioral responses. j Classification error across quiescence durations. The minimum defines the optimal threshold (8 min) separating fast and slow responses. k Average response latency for animals quiescent less vs. more than 8 min before food stimulation (n = 53; ****p < 0.0001). l Sleep time during 72 h under LD (n = 33) and DD (n = 24) in WT N. vectensis. m Average sleep time during ZT18-6 vs. ZT6-18 under LD (n = 33; ****p < 0.0001). n LSP analysis of sleep under LD and DD. o Sleep time during 72 h under LD (n = 34) and DD (n = 26) in NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis. p Average sleep time during ZT18-6 and ZT6-18 under LD (n = 34; ****p < 0.0001). q LSP analysis of sleep under LD and DD. r Open and closed tentacle posture. s Average sleep time for open or closed posture (n = 33; **p < 0.01). t Sleep time in Ctl (n = 22) and SD (n = 24) animals before and after SD (ZT20-ZT4). u Average sleep time in Ctl and SD animals at ZT10-16 (Ctl: n = 22, SD: n = 24; *p < 0.05). v Sleep time in Ctl (n = 24) and SD (n = 28) animals before and after SD (ZT8-ZT16). w Average sleep time in Ctl and SD animals at ZT22-ZT4 (Ctl: n = 24, SD: n = 28). Boxplots show median (center line), interquartile range (box), and minima/maxima (whiskers); individual data connected in (d, m, p); mean (black cross) in (h, k, s, u, w). Data in (c, l, o, t, v) are presented as mean ± SEM. White, black, and red horizontal lines represent periods of light, dark, and SD, respectively. Wilcoxon signed-rank test (one-tailed) for (d, m, p). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (one-tailed) for (h, k, s, u, w). LSP analysis with p < 0.01 if period indicated. p > 0.05 if ns (n, q).

This characterization of sleep enabled us to convert mobility data to sleep time (Supplementary Fig. 2a-e). The crepuscular N. vectensis showed rhythmic locomotor activity and an average sleep duration of 25 ± 2.3 min during ZT18-ZT6 and 14 ± 1.8 min during ZT6-ZT18, with a sleep period of 23.4 h under LD conditions (mean ± SEM). Similarly, the rhythmic sleep period was 22.5 h under DD (Fig. 2l-n, Supplementary Fig. 3a, b), suggesting that sleep is regulated by the circadian clock in N. vectensis. To further differentiate between light- and circadian-regulation of sleep, we monitored sleep under forced desynchrony (LDLD). While the rhythmic period of locomotor activity was 22.2 h and controlled by the clock, sleep period was 11.7 h (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f, i, j). These results suggest that although sleep is primarily regulated by the circadian clock it can also be modulated by light in N. vectensis. To understand the hierarchy of light- and intrinsic clock-regulation of sleep, we monitored sleep in NvClkΔ mutant34 (NvClkΔ/Δ) N. vectensis. NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis showed bimodal sleep/wake rhythms (periods of 12.25 h and 25.24 h) under LD and this rhythm was abolished under DD (Fig. 2o–q, Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). Under LDLD, the sleep/wake cycle followed the 6 h alternating light/dark rhythm (Supplementary Fig.3k, l). These findings demonstrate that the transcription factor NvClk is essential for maintaining clock-controlled sleep in N. vectensis. To further characterize sleep, we examined species-specific association with posture. Sleep time was monitored in animals displaying closed or open tentacles (Fig. 2r). Although close or open tentacle posture did not strictly differentiate sleep from wake state; i.e. animals with closed tentacles can be awake and vice versa, the closed tentacle N. vectensis slept 2.1-fold more than open tentacles N. vectensis at the peak of the sleep period (ZT23, Fig. 2s). To test whether homeostatic process regulates sleep, we sleep-deprived the N. vectensis for 8 h during sleep period (ZT20-ZT4) using gradual and gentle water exchange once per hour (Supplementary Movie 4). Following SD, sleep-deprived animals slept 1.24-fold more than control animals (Fig. 2t, u), indicating a homeostatic sleep drive. In contrast, control SD during the activity period (ZT8-ZT16) did not induce a sleep rebound (Fig. 2v, w). Altogether, while sleep can be modulated by light, a combination of circadian and homeostatic processes are the primary regulators of sleep in the crepuscular N. vectensis.

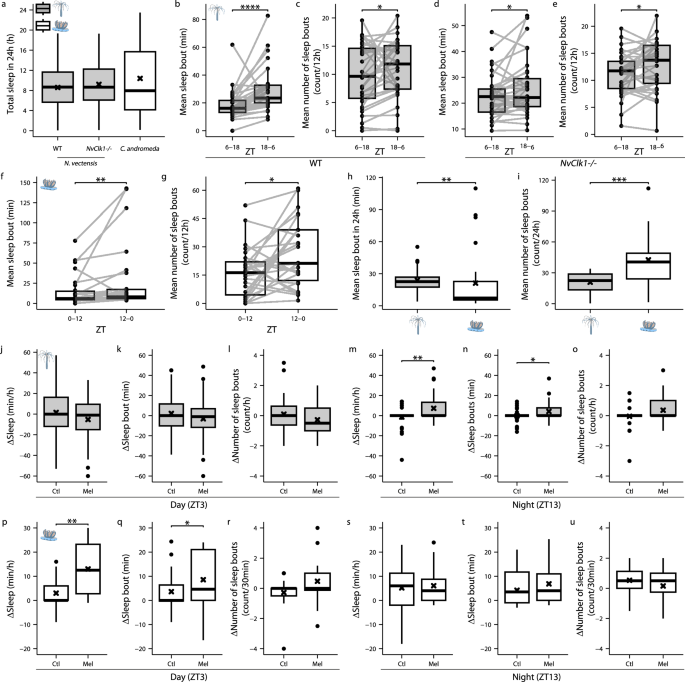

Inter-species comparison of sleep architecture revealed that melatonin consolidates sleep independently of the animal chronotype

The establishment of sleep criteria in two cnidarians, which sleep at different times of the day, enabled us to study species-specific changes in sleep architecture and regulatory mechanisms. The analysis of sleep time revealed nocturnal sleep in C. andromeda, and a crepuscular rhythmic sleep/wake cycle in WT N. vectensis, which was abolished in NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis under constant conditions (Fig. 2). However, total sleep time over 24 h was similar in C. andromeda, WT and NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis (Fig. 3a). To determine sleep patterns, we quantified the length and number of sleep bouts during the sleep and wake periods of each species. We found longer sleep bout durations and a higher number of sleep bouts at ZT18-6 compared to ZT6-18, under LD, in both WT (Fig. 3b, c) and NvClkΔ/Δ (Fig. 3d, e) N. vectensis. Similarly, under LD conditions, sleep bout length and the number of sleep bouts increased during the night (ZT12-0) in the diurnal C. andromeda (Fig. 3f, g). Inter-species comparison of sleep architecture revealed that although total sleep time was similar (Fig. 3a), the average sleep bout length was shorter by 2.8 min (Fig. 3h), and the mean number of sleep bouts was approximately two-fold higher (Fig. 3i) in C. andromeda compared to N. vectensis. These results show that, like humans, both cnidarian species spend approximately one-third of their lives sleeping (Fig. 3a). However, sleep is more consolidated in N. vectensis, i.e., longer and less fragmented sleep bouts, compared to C. andromeda.

a Total sleep time during 24 h in WT, NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis (gray) and C. andromeda (white) (n: N. vectensis: WT = 33, NvClkΔ/Δ=34, C. andromeda = 26). b Mean sleep bout length in WT N. vectensis (n = 33; ****p < 0.0001) during the wake (ZT6-18) and sleep (ZT18-6) periods. c Mean number of sleep bouts in WT N. vectensis (n = 33; *p < 0.05) during the wake (ZT6-18) and sleep (ZT18-6) periods. d Mean sleep bout length in NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis (n = 34; *p < 0.05) during the wake (ZT6-18) and sleep (ZT18-6) periods. e Mean number of sleep bouts in NvClkΔ/Δ N. vectensis (n = 34; *p < 0.05) during the wake (ZT6-18) and sleep (ZT18-6) periods. f Mean sleep bout length in C. andromeda during the wake (ZT0-12) and sleep (ZT12-0) periods (n = 26; **p < 0.01). g Mean number of sleep bouts in C. andromeda during the wake (ZT0-12) and sleep (ZT12-0) periods (n = 26; *p < 0.05). h Mean sleep bout length over 24 h in WT N. vectensis (gray) and C. andromeda (white) (n: N. vectensis: WT = 33, C. andromeda = 26; **p < 0.01). i Mean number of sleep bouts over 24 h in WT N. vectensis (gray) and C. andromeda (white) (n: N. vectensis: WT = 33, C. andromeda = 26; ***p < 0.001). j–u The changes in sleep architecture post melatonin (Mel; 100 mM) or ethanol control (Ctl). N. vectensis (Ctl; n = 36, Mel; n = 36) treated at ZT3 (sleep phase): (j–l). N. vectensis (Ctl; n = 36, Mel; n = 36) treated at ZT13 (wake phase): (m–o). C. andromeda (Ctl; n = 16, Mel; n = 16) treated at ZT3 (wake phase): (p–r). C. andromeda (Ctl; n = 16, Mel; n = 16) treated at ZT13 (sleep phase): (s–u). Significance level in (m) and (p) represents **p < 0.01 and in (n) and (q) *p < 0.05. Boxplots show median (center line), interquartile range (box), minima/maxima (whiskers); mean (black cross) in (a,h–u); individual data connected in (b–g). Wilcoxon signed-rank test (one-tailed) for (b-g). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (two-tailed) for (a,h–i). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (one-tailed) for (j–u).

The presence of circadian and homeostatic regulation of sleep in cnidarians suggests a common neuroregulatory mechanism. The melatonin hormone is secreted from the pineal gland during the night and mediates rhythmic daily physiological and behavioral processes in vertebrates35,36. However, its role in invertebrates remains poorly understood37,38. We tested the effect of melatonin on sleep in the diurnal C. andromeda and crepuscular N. vectensis. While melatonin treatment did not affect sleep during the rest periods of N. vectensis (ZT3) and C. andromeda (ZT13) (Fig. 3j–l, s–u), sleep time, sleep bout duration, and the number of sleep bouts increased during the active phase in both N. vectensis (ZT13) and C. andromeda (ZT3) (Fig. 3m–o, p–r). These results suggest an evolutionarily conserved role of melatonin in sleep regulation across animals with different chronotypes.

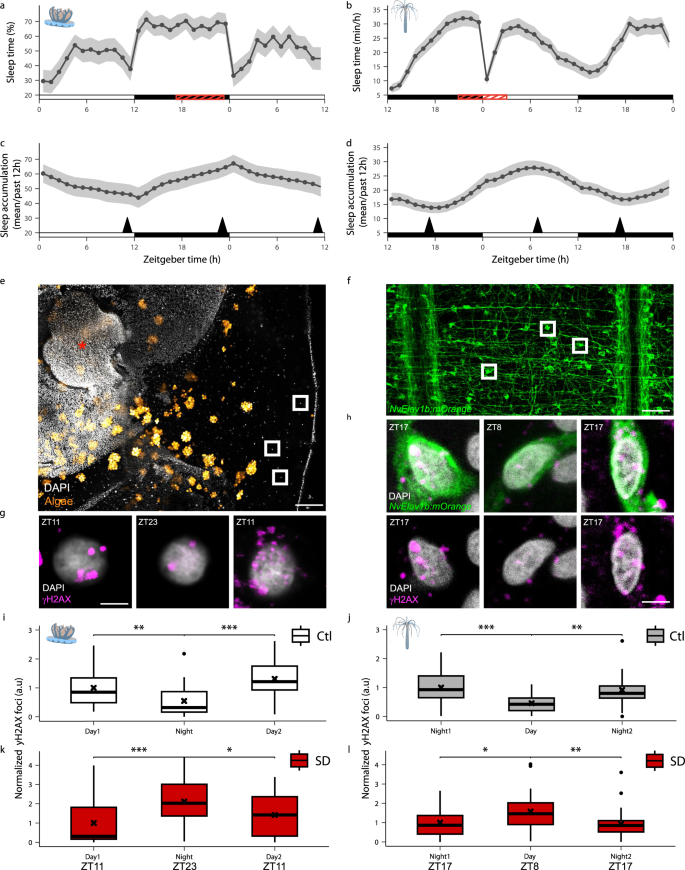

Sleep relieves the accumulation of DNA damage in both diurnal and crepuscular cnidarians

The presence of sleep in cnidarians indicates that sleep evolved independently of the brain. Studies in fish have shown that sleep decreases DNA damage and is essential for the health of single, non-dividing neurons18,19. To investigate cellular factors that might have driven the evolutionary emergence of sleep in cnidarians, we monitored DNA damage levels in single cells of N. vectensis and C. andromeda during the sleep/wake cycle and following SD (Fig. 4a–d). We hypothesized that DNA damage would peak and decline following extended wake and sleep, respectively. To identify the time points of maximal and minimal sleep pressure, we calculated the average sleep time over the past 12 h that preceded each time point. Both C. andromeda and N. vectensis were sampled at the end of their wake (ZT11 and ZT17) and sleep (ZT23 and ZT8) phases (Fig. 4a, b), where wake and sleep accumulation peaked (Fig. 4c, d). DNA damage was quantified using immunohistochemical assays with an antibody against the phosphorylated histone H2AX (γH2AX), a well-established biomarker of cellular response to DNA damage39. The number of nuclear γH2AX foci was quantified in the neuron-enriched mesogleal surface of the peri-rhopalial tissue40, located adjacent to individual rhopalium of C. andromeda (Fig. 4e, g), and in mOrangeCAAX-positive neurons of transgenic tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX)27 N. vectensis (Fig. 4f, h). Under LD, the number of γH2AX foci increased at the end of the wakefulness period in C. andromeda (ZT11) and N. vectensis (ZT17) and reduced at the end of the sleep period in C. andromeda (ZT23) and N. vectensis (ZT8) (Fig. 4i, j). The opposite timing of DNA damage reduction between C. andromeda and N. vectensis was aligned with their species-specific chronotype and daily timing of sleep. To determine the effect of homeostatic sleep pressure, C. andromeda and N. vectensis were sleep-deprived for 6 h (ZT17-ZT23) and 8 h (ZT20-ZT4), respectively. Following SD, the number of γH2AX foci increased in C. andromeda (ZT23) and N. vectensis (ZT8) and subsequently decreased to baseline levels following sleep recovery in both species (Fig. 4k, l). These results demonstrate that DNA damage accumulates during wakefulness and decreases during sleep in both diurnal and crepuscular cnidarians. Furthermore, these findings suggest that decreasing DNA damage during sleep is an evolutionarily conserved cellular function that may have contributed to the emergence of sleep in early metazoans.

a,b Average sleep time during 36 h under LD in C. andromeda (a) and N. vectensis (b). White, black, and red horizontal bars represent light, dark, and SD periods, respectively (C. andromeda: ZT17-23, N. vectensis: ZT20-ZT4). c, d Sleep time accumulation of the previous 12 h (sliding average) in C. andromeda (c) and N. vectensis (d) during 36 h under LD. Black arrowheads indicate sampling time for the DNA damage assay presented in (i–l). e Confocal z-projection of a C. andromeda rhopalium and adjacent peri-rhopalial tissue. White squares mark representative single nucleus in the mesoglea. Red asterisk indicates rhopalium. Scale bar 150 μm. f Confocal z-projection showing the mOrange-positive endodermal nervous system in tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX) N. vectensis. White squares mark representative single neurons. Scale bar 100 μm. g Representative images of cells in the peri-rhopalial tissue of C. andromeda sampled at ZT11, ZT23, and the following day (Day2 ZT11). Nucleus stained by DAPI (gray), and γH2AX foci (magenta) are stained using immunohistochemistry. Scale bar 4 μm. h Representative images of γH2AX staining (magenta) in mOrange-positive neurons (green) of tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX) N. vectensis sampled at ZT17, ZT8, and the following night (Night2 ZT17). Nucleus stained by DAPI (gray). Scale bar 2 μm. i, k Normalized number of γH2AX foci per nucleus of control and sleep-deprived C. andromeda under LD. i Control: Day1 (n = 24, 1.00 ± 0.64), Night (n = 22, 0.55 ± 0.55), Day2 (n = 26, 1.31 ± 0.63). k Sleep-deprived: Day1 (n = 27, 1.00 ± 1.09), Night (n = 31, 2.11 ± 1.13), Day2 (n = 28, 1.42 ± 1.12). Values are mean ± s.d. (n=rhopalia from 8-10 animals per time point). j, l Normalized number of γH2AX foci per nucleus of control and sleep-deprived N. vectensis under LD. j Control: Night1 (n = 19, 1.00 ± 0.52), Day (n = 19, 0.46 ± 0.30), Night2 (n = 15, 0.92 ± 0.64). l Sleep-deprived: Night1 (n = 24, 1.00 ± 0.75), Day (n = 26, 1.57 ± 1.02), Night2 (n = 25, 0.92 ± 0.80). Values are mean ± s.d. (n=animals). Data in (a–d) are presented as mean ± SEM. Boxplots show median (center line), interquartile range (box), minima/maxima (whiskers), and mean (black cross) in (i–l). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (two-tailed) for (i–l). Significance level in (i–l) represents *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

DNA damage increases sleep pressure in C. andromeda and N. vectensis

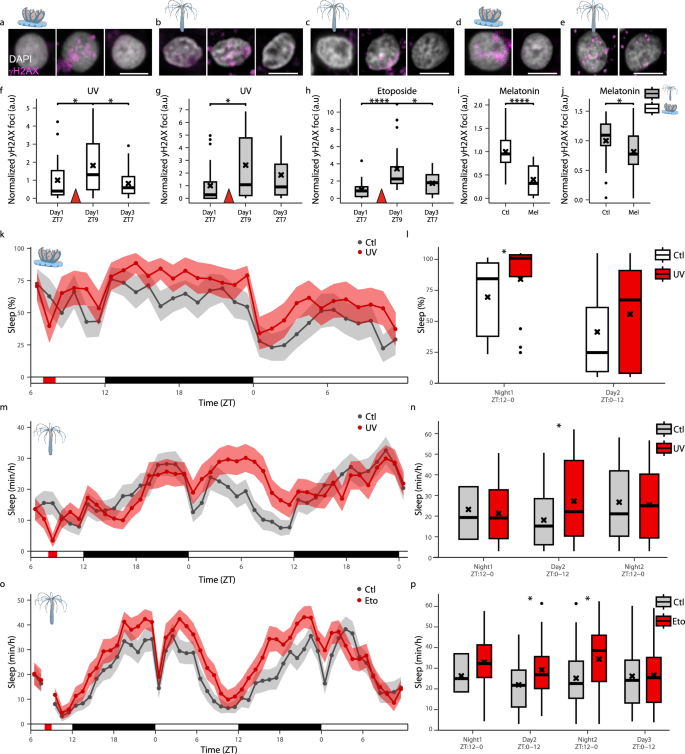

The correlation between sleep drive and cellular stress (Fig. 4) raised the possibility that environmental and intrinsic factors, disrupting DNA integrity, promote sleep in cnidarians. UV radiation is a potent DNA damage agent and an ancient pervasive atmospheric stressor impacting marine invertebrates41,42,43. To determine the effect of UV radiation on DNA damage and sleep, we exposed C. andromeda and N. vectensis to 15 min and 60 min, respectively, of UVB radiation44 (312 nm) during the day (ZT8). In C. andromeda and N. vectensis, the number of γH2AX foci increased one hour after UV exposure (Fig. 5a, b, f, g). Subsequently, nighttime and daytime sleep increased in C. andromeda (Fig. 5k, l) and N. vectensis (Fig. 5m, n), respectively. Notably, following sleep recovery, the animals remained viable, and two days later, the levels of DNA damage reduced in C. andromeda (Fig. 5a, b, f, g). These results suggest that UV-mediated induction of DNA damage increases sleep pressure. Since UVB may also affect the behavior of cnidarians in alternative pathways45, we treated N. vectensis with the mutagenic compound Etoposide46. While UVB induces oxidative stress and damage to DNA bases, Etoposide inhibits the topoisomerase II enzyme and stabilizes DNA double-strand break formation. Similar to the effect of UV, Etoposide treatment abruptly increased the number of γH2AX foci (Fig. 5c, h). The animals then increased sleep during the following day and night (Fig. 5o, p), and DNA damage was reduced (Fig. 5c, h). Consistent with these findings, melatonin treatment, which promoted sleep during the species-specific active phase in both N. vectensis (ZT13) and C. andromeda (ZT3) (Fig. 3m, p), reduced γH2AX foci levels in both species (Fig. 5d, e, i, j). Together, these results show bidirectional interactions between sleep and DNA damage in early divergent lineage. Moreover, these inter-species comparative findings suggest that environmental factors, such as UV radiation and soluble mutagenic compounds, which can induce DNA damage and cellular stress, may have contributed to the evolutionary emergence of sleep in cnidarians.

a–e Representative images of γH2AX staining (magenta) in cells (DAPI, gray) of C. andromeda (a, d; scale bar 4 μm) and N. vectensis (b, c, e; scale bar 3 μm) treated with UV (a, b), Etoposide (Eto, c), and melatonin (d, e; Mel). f–h Normalized number of γH2AX foci per nucleus at ZT7 (Baseline), ZT9 (1 h post-treatment), and ZT7 (48 h post-treatment) after UV (f, g) or Eto (h) treatments, in C. andromeda (f) and N. vectensis (g, h). f Red triangle represents the end of the UV treatment (15 min post ZT7). (g, h) Red triangle represents the end of the UV and Eto treatments (ZT8). (f) C. andromeda UV: ZT7 (n = 23, 1.00 ± 1.18), ZT9 (n = 24, 1.81 ± 1.56), Day3 ZT7 (n = 22, 0.82 ± 0.78), *p < 0.05. g N. vectensis UV: ZT7 (n = 27, 1.00 ± 1.55), ZT9 (n = 27, 2.62 ± 2.73), Day3 ZT7 (n = 21, 1.85 ± 2.16), *p < 0.05. h N. vectensis Eto: ZT7 (n = 22, 1.00 ± 1.02), ZT9 (n = 24, 3.42 ± 2.92), Day3 ZT7 (n = 22, 1.74 ± 1.35), *p < 0.05 and ****p < 0.0001. i, j Normalized number of γH2AX foci per nucleus at ZT6 (i) and ZT16 (j). i C. andromeda (melatonin): Control (Ctl) (n = 24, 1.00 ± 0.37), Mel (n = 24, 0.40 ± 0.34), ****p < 0.0001. j N. vectensis (melatonin): Ctl (n = 22, 1.00 ± 0.39), Mel (n = 23, 0.81 ± 0.39), *p < 0.05. (k-p) Average sleep in C. andromeda (k, l; Ctl; n = 13, UV; n = 13; *p < 0.05) and N. vectensis (m–p); UV experiment: Ctl; n = 35, UV; n = 31, *p < 0.05; Eto experiment: Ctl; n = 24, Eto; n = 24, *p < 0.05) before and after UV exposure (k, m) or Eto treatment (o). The average sleep in UV-exposed (l, n) and Eto-treated (p) C. andromeda (l) and N. vectensis (n, p). White, black, and red horizontal lines represent periods of light, dark, and periods of UV exposure (k, m) or Eto treatment (o). Boxplots show median (center line), interquartile range (box), minima/maxima (whiskers), and mean (black cross) in (f–j, l, n, p). Data in (k, m, o) are presented as mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (two-tailed) for (f–h). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (one-tailed) for (i, j). Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon (one-tailed) for (l, n, p). Values are mean ± s.d. C. andromeda: n=rhopalia from 11 animals per time point (f) and 8 animals per melatonin group (i); n=animals (k, l). N. vectensis: n=animals.

Discussion

Sleep is a vulnerable behavioral state, yet it is ubiquitous across animal species with a nervous system. This study proposes that sleep is an adaptive solution to the cellular cost of wakefulness. Wakefulness is associated with continuous sensory inputs and activity of irreplaceable neurons, enhanced cellular metabolism, and increased locomotion9,10,11,12. Particularly when combined with exposure to environmental mutagens, extended wakefulness can result in cellular stress. To investigate the evolution of sleep function, we characterized the sleep architecture of two cnidarians: the diurnal C. andromeda and crepuscular N. vectensis. Like humans, both species require a total of approximately 8 h of sleep per day. While sleep is regulated by homeostatic pressure in both species, it is also regulated by the light and the circadian clock in C. andromeda and N. vectensis, respectively. Despite their divergent chronotype, both natural and melatonin-induced sleep reduce DNA damage levels, which increase during wakefulness, in both species. The relationship between sleep and DNA damage is bidirectional, and the induction of DNA damage can promote sleep pressure. Altogether, these findings suggest that sleep evolved to support cellular maintenance and preserve genomic integrity in ancient cnidarians possessing a simple nervous system.

In mammals, electroencephalogram (EEG) patterns and behavioral criteria are used to define sleep47. In most non-mammalian vertebrates and invertebrates, EEG-based diagnostics are limited, making behavioral criteria the primary method for defining sleep1. Nevertheless, the behavioral sleep criteria have been supported by corresponding changes in neuronal activity in a few non-mammalian animals5,48,49. The recent identification of sleep-like behavior in cnidarians suggests that sleep predates the evolution of centralized nervous systems. Sleep-like states have been documented in Cassiopea4 and H. vulgaris3, and behavioral quiescence was observed in corals and box jellyfish in their natural habitat50,51,52. However, sleep had not previously been identified in the Anthozoans, and a specific arousal threshold was not determined in C. andromeda. Using arousal threshold experiments, we defined sleep as a minimum of 8 min of quiescence state in N. vectensis and 3 min under 37 pulses/min in C. andromeda. Although we observed a correlation between tentacle contraction and sleep in N. vectensis, both closed and open tentacle postures were observed during both sleep and wake states. In addition, C. andromeda maintained low but continuous pulsation activity while sleeping, supporting the idea that sleep cannot be defined solely by immobility or tentacle posture50,53. Likewise, migrating birds and marine mammals can sleep while moving, utilizing unihemispheric sleep54,55.

The quantitative measure of sleep enabled us to monitor sleep in the natural habitat, providing insights into how organisms regulate sleep under ecological conditions. In C. andromeda, we developed a predictive model for sleep duration across different organism sizes in wild populations inhabiting Key Largo, FL. These animals exhibited similar sleep duration and architecture as in controlled laboratory conditions, including short midday naps despite differences in salinity and temperature. These findings suggest that internal, species-specific cellular mechanisms shape the sleep pattern. Accordingly, we characterized the hierarchy of sleep regulatory mechanisms in two cnidarian species adapted to distinct ecological niches. Light and homeostatic drive were the predominant sleep regulatory processes in C. andromeda, while homeostatic drive and the circadian clock control sleep in N. vectensis. The light-dependence regulation may be attributed to the C. andromeda symbiosis with endosymbiotic dinoflagellates, because photosynthesis-driven byproducts, such as ROS, increase cellular stress, DNA damage56,57,58,59 and sleep pressure. The rhythmic activity of the symbiotic algae is likely physiologically deficient under constant light or dark conditions, potentially disrupting the light-dependent rhythmic sleep/wake cycle in C. andromeda. In contrast, the sleep/wake cycle is regulated by the clock even under constant environmental conditions in the non-symbiotic and crepuscular N. vectensis. Indeed, oxygen consumption, and possibly also ROS levels, are regulated by the circadian clock in N. vectensis60, supporting the idea that intrinsic molecular clocks control the timing of sleep in cnidarians lacking photosymbiosis.

The neuroendocrinological mechanisms that regulate sleep in cnidarians is unknown. We showed that despite their opposing chronotypes, melatonin treatment promoted sleep and reduced DNA damage levels in both species during their respective active phases, suggesting a conserved role for this hormone in sleep modulation. Future extended monitoring of sleep for several days may reveal an additional circadian phase-shifting effect of melatonin. Similarly, exogenous melatonin promoted sleep in diurnal species, such as zebrafish61, and reduces locomotor activity and increases sleep in nocturnal species, such as flatworms62 and mice63, respectively. Melatonin is secreted by the pineal gland and binds to melatonin receptors in vertebrates35,36. However, although endogenous melatonin production was demonstrated in basal metazoans64, the mechanism of action is less understood in invertebrates. In the roundworm C. elegans, melatonin activates a specific potassium channel65, and similar channels may play an evolutionarily conserved role in mediating the sleep effect of melatonin in cnidarians. Future research in cnidarians, including genetic manipulations, may determine the possible role of melatonin as an antioxidant, explain the mechanisms underlying its regulation and elucidate how pharmacological melatonin treatment contributes to sleep and DNA damage regulation in both nocturnal and diurnal animals.

In both C. andromeda and N. vectensis, we observed the accumulation of neuronal DNA damage during wakefulness, which was alleviated during sleep, whereas SD impaired this recovery process. These results in simple nerve nets support findings in other evolutionarily derived animals and humans18,20,21,66 and suggest that the balance between DNA damage and repair is insufficient during wakefulness, and sleep provides a consolidated period for efficient cellular maintenance in individual neurons. Across evolution, as the number of neurons and the complexity of neuronal networks increase67, sleep may have evolved to confine unsynchronized cellular maintenance, and coordinate neuronal activity and maintenance across interconnected circuits, ensuring functional stability.

Understanding which homeostatic internal and environmental factors drive sleep in basal animals could shed light on the evolutionary emergence of sleep behavior. In worms, flies, fish, and mice, sleep is necessary to recover from cellular stress, induced by factors such as ROS and UV light8,19,68,69. The symbiotic diurnal C. andromeda inhabits shallow tropical waters and are exposed to high levels of UV radiation70. In accordance, we found that UV exposure increased sleep pressure in C. andromeda. However, a similar effect was observed in the crepuscular N. vectensis, which inhabits estuarine environments with fluctuating light exposure, often burrowing in sediment during the day. Thus, we suggest that a downstream mechanism, i.e., UV-mediated DNA damage, is a homeostatic driver of sleep in cnidarians. Indeed, we showed that Etoposide, a pharmacological inducer of DNA damage, promoted sleep in N. vectensis, suggesting a positive correlation between DNA damage accumulation and sleep pressure across evolution. These findings are supported by our work in zebrafish showing that UV radiation, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of nuclear proteins, and neuronal activity can induce DNA damage and promote sleep18,19. Moreover, sleep-dependent reductions in DNA damage have been reported also in flies, mice, and humans20,21,71, and melatonin improved the repair of oxidative DNA damage in night shift workers66.

Cnidarians are emerging as genetically tractable, translucent models for studying evolutionary neuroscience26,72. We showed that sleep supports neuronal recovery in cnidarians. Beyond cellular repair, neuronal health is likely tied to additional sleep functions, such as learning and memory consolidation73. Associate learning has recently been demonstrated in N. vectensis and box jellyfish72,74, and future studies in cnidarians can elucidate how sleep optimizes cellular maintenance and consolidation of memory at the level of single cell within simple nerve nets of live animals. The molecular tools developed in our work and in other cnidarian studies75 offer a unique opportunity to identify conserved sleep-associated cellular markers, which could help characterize sleep at the cellular level. Since sleep has traditionally been classified based on movement and arousal thresholds in invertebrates, uncovering molecular signatures of sleep in cnidarians may help to characterize sleep in additional basal organisms, such as coral colonies, which consist of thousands of interconnected polyps. Whether coral polyps sleep simultaneously or in a coordinated alternating manner remains unknown, but studying their nerve net dynamics could provide clues about the evolutionary origins of local sleep regulation76. Moreover, considering that the interplay between the circadian clock and genomic stability has been shown in non-neuronal mammalian cultured cells, fungi and cyanobacteria77,78,79,80, sleep-like states may have preceded the evolution of neurons, originally evolved to support synchronized and consolidated periods of cellular maintenance.

Methods

C. andromeda and N. vectensishusbandry

C. andromeda jellyfish were initially collected from the Gulf of Eilat and later raised and reproduced in the laboratory. The animals were reared in artificial seawater (ASW, OmegaSea, 39-40 ppt) at a 24 °C–25 °C with a pH of 8.1–8.3. A water cooler and heater were used to maintain a constant temperature. A deuterium-depleted water (DDW) compensation system was used to maintain salinity levels. Animals were raised under a 12 h day/12 h night cycle (LD) using 2400 W Metal Halogen 14,000 K light sources providing approximately 100 PPFD at the animal level, located 20 cm above the water surface. The animals were housed and monitored in a 113-liter closed water system equipped with a waste filtration system and a protein skimmer. Waste products were kept close to 0 ppm ammonia, 0 ppb phosphorus, 0 ppm nitrite, and 0 ppm nitrate. C. Andromeda were fed daily with brine shrimp (Artemia nauplii) at noon. Animals with bell diameters of 5-7.5 cm, in a relaxed state, were randomly assigned to each experimental group. The C. Andromeda genotype was validated by sequencing the cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) gene81. Whole genomic DNA was extracted using the Minikit NucleoSPin tissue (NucleoSpin, REF 740952.50), and DNA fragment amplification was performed using the following degenerated primers: Forward: 5’-ACNAAYCAYAAAGATATHGG-3’, Reverse: 5’-TGGTGNGCYCANACNATRAANCC-3’.

N. vectensis were raised in ASW (OmegaSea, 12ppt) in a closed system at 17 °C under constant darkness and fed daily with Artemia nauplii at noon. Spawning of gametes and fertilization was performed according to established protocol82. In brief, the temperature was raised to 25 °C for 9 h, and males and females were exposed to strong white light. 3 h later, oocytes were mixed with sperm to enable fertilization. To genotype NvClkΔ mutant and WT N. vectensis, genomic DNA was extracted using the Minikit NucleoSPin tissue (NucleoSpin, REF 740952.50). A fragment of the NvClk gene was amplified using the following primers: forward 5’-ACCCCACTGAGTGACCTCTT-3’ and reverse 5’-ATACGCCTGCGCTATACACC-3’. The PCR products were then loaded on a 3% Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) agarose gel supplemented with GelStar Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). The genotype of each animal was determined based on the size of the PCR products: NvClkΔ/Δ - 120 bp; WT - 100 bp. The gel-based genotyping was confirmed by sequencing in selected animals.

Behavioral tracking and analysis of C. andromeda

Two modular water systems (Aquazone Ltd, Israel) were designed to monitor the behavior of 9 or 16 jellyfish simultaneously while maintaining controlled light, temperature, and salinity conditions. The systems consisted of 9 or 16 clear perspex chambers of 10 x 10 x 10 cm or 7 x 7 x 10 cm for individual jellyfish, respectively (Fig. 1a). These apparatuses were kept inside a 55 x 50 x 30 cm tank, connected to a waste filtration system, a protein skimmer, a water heater, and a DDW water compensation system. C. andromeda were kept under 12 h of light (five 50 W LED lights providing 100–200 PPFD at the animal level) and 12 h of darkness (LD) and constantly illuminated with low-intensity IR LED lights. Prior to each experiment, C. andromeda were acclimated in the recording system, one individual per chamber, for 2-3 days. An IR camera (Dahua Technology, Hangzhou, China) with an IR filter was used to record mp4 videos at resolution of 1920 × 1200 and 20 frames per second (fps). The mp4 videos were converted to avi files using the FFmpeg software (FFmpeg, Irvington, NJ, USA). MATLAB Version: 9.8.0 (R2020a)83 and a lab-made script were used to determine pulsation behavior. The change in the average pixel intensity was measured for each frame, producing a pulse trace. A rectangular region of interest (ROI) was selected for each jellyfish. The smoothed average pixel intensity was calculated using a Gaussian moving window and was subtracted from the data to control for low-frequency oscillations of the data. Pulsation events were counted using the peak of the pulse trace (Fig. 1b), and the mean activity was analyzed during the first 20 min of each hour along day and night. Sleep architecture was analyzed using the full duration of the first 24 h of the video recording to ensure the continuity of the data. Jellyfish that changed their horizontal to a vertical position or anomalous animals exhibiting pulsing behavior three standard deviations below or above the mean were excluded. The oscillation frequencies were evaluated based on the average values of each experiment using the Lomb-Scargle Periodogram (LSP) from the ‘Lomb’ library84 on R85 with a p < 0.01 threshold. To assess the change in arousal threshold, the jellyfish were stimulated repeatedly every hour at night (ZT13-ZT19) using a 1 s 100–200 PPFD light pulse. A response was defined as a reduction of 2 standard deviations in the inter-pulse intervals (IPI) compared to the distribution of IPIs before the stimulation, within a time window of 10 s after the stimulus. A threshold-based optimization algorithm was used to determine the optimal behavioral parameters to distinguish between slow and fast responses (i.e., elevated arousal threshold; Fig. 1g, j). For each candidate threshold (e.g., pulsation rate), responses were split into two groups: below and above the threshold. We then summed all Euclidean distances of these responses from the mean value of their respective groups (i.e., error value). Thus, the behavioral value that optimally divided a group of fast responses and slow responses results in the lowest error value. In SD experiments, the animals were stimulated repeatedly with a gentle water pulse using thin tubes connected to a water pump and a computer clock. These 10 min pulses of water were applied every 10 min for 6 h at ZT17-ZT23. Field experiments were conducted in May in the native habitat of Cassiopea at Key Largo, FL. Light intensities ranged between 400-1500 PPFD at a depth of 0.3–1.5 m at the peak of the day, salinity was 31.5 ppt and Temperature was 26.8 °C. The pulsation rate was monitored manually by counting the number of pulses per minute every hour in 30–40 animals during the day and night (total of 662 animals). Subsequently, the diameter of the relaxed bell of each individual was measured.

Behavioral tracking and analysis of N. vectensis

Locomotor activity of individual N. vectensis was monitored using a custom-made temperature-controlled (20 °C) water system equipped with an IR camera (Dahua, Binjiang District, Hangzhou, China). Animals of similar size (1-2 cm), genetic background, and age were distributed individually into wells of four six-well plates (Fig. 2a) and were subject to alternating white light Illumination with intensity of 17 PPFD (Sylvania Lightning Solution, Wilmington, MA, USA). MATLAB script was generated based on H. vulgaris sleep tracking methodology3 to analyze the locomotor activity and sleep. We measured changes in the pixel value between two consecutive frames at 5 s intervals (Supplementary Fig. 2a-e). Noise was reduced by subtracting the minimum pixel change of the individual. To set the minimum threshold of locomotor activity, pixel changes of MgCl2-treated paralyzed animals were quantified. These changes were considered immobility. The ratio of frames with detectable movements was calculated in a 1 min bin (i.e., fraction movement) and defined as quiescence if movement was not detected in more than 50% of the frames per 1 min bin (i.e., fraction movement<0.5). To assess the change in arousal threshold, the polyps were stimulated with either light or food. Polyps were stimulated with three different light intensities ( + 5, +50, +500 PPFD, above the 17 PPFD baseline) during the day (ZT10) for 30 min (Supplementary Fig. 2f–k). Food stimulation was performed by application of “Reef Energy Plus” solution (Red Sea, Israel). A response-to-stimulus was defined as 30 s of continuous movement above the threshold. A threshold-based optimization algorithm was used to determine the optimal behavioral parameters to distinguish between slow and fast responses (i.e., elevated arousal threshold; Fig. 2g, j) as is described for C. andromeda. Sleep durations were summed in hourly bins, and the average and standard errors were calculated for all tested animals. Since N. vectensis showed crepuscular behavior (i.e., active at dusk), we used a data-driven approach to define sleep (ZT18-6) and wake (ZT6-18) periods in a 12 h time window. Sleep architecture data were analyzed using continuous 60 h movies starting at ZT18. In SD experiments, the animals were stimulated by gentle water exchange once per hour during their peak of sleep period (ZT20-ZT4) and peak of activity period (ZT8-ZT16; Supplementary Movie 4) and sleep was monitored before and after the SD. The oscillation frequencies were evaluated based on the average values of each experiment using Fourier analysis-based software LSP with a p < 0.01 threshold. Open or closed posture was manually annotated from a single video frame. Animals were categorized based on the number of tentacles deployed outside of their body. Animals that showed at least two visible tentacles were classified as ‘open’.

Melatonin treatments in C. andromeda and N. vectensis

For both sleep and DNA damage assays, animals were first habituated. Specifically, C. andromeda and N. vectensis were entrained and maintained in the behavioral systems described above for 72 h under LD conditions. In the C. andromeda system, water circulation was terminated one hour prior to melatonin treatment due to the high volume of constant water exchange in the system. Both species were treated with either 100 μM melatonin (diluted in ethanol) or ethanol for control, at ZT3 and ZT13. These time points were selected to correspond to their respective periods of sleep (ZT3 for N. vectensis, ZT13 for C. andromeda) and wakefulness (ZT13 for N. vectensis, ZT3 for C. andromeda) for both species. In C. andromeda, behavior was recorded 30 min before and during melatonin administration. In N. vectensis, behavior was recorded 60 min before and during melatonin treatment. The delta effect (Fig. 3j–u) was calculated by subtracting the mean post-treatment values from the mean pre-treatment values of either melatonin or ethanol treatment. In DNA damage quantification assays, animals were treated with melatonin for 3 h, starting at ZT13 for N. vectensis and ZT3 for C. andromeda at their respective wake period, and were then fixed in 4% PFA. For N. vectensis, the upper body column was mounted on a slide, and cells in the epithelium layer (ectodermis) were imaged. For C. andromeda, three independent rhopalia were dissected from each animal (total of eight animals per Ctl and Mel groups) and DNA damage was quantified in cells located in the mesogleal surface of the peri-rhopalial tissue adjacent to each rhopalium.

Irradiation of UV in C. andromeda and N. vectensis

For both sleep and DNA damage assays, animals were first habituated. Specifically, C. andromeda and N. vectensis were entrained and maintained in the behavioral systems described above for 72 h under LD conditions. A dark plastic barrier divided and isolated UV-treated animals from controls in the behavioral monitoring systems. For C. andromeda, sleep was recorded for 30 h; for N. vectensis, 42 h. At ZT8, half of the animals were exposed to 312 nm UVB (Spectroline® E-Series UV lamp, 20 cm above the animals): 15 min in C. andromeda and 1 h in N. vectensis. To quantify DNA damage, at each time point, UV-treated and control C. andromeda and N. vectensis were fixed in 4% PFA before (ZT7), 1 h (ZT9), and two days (ZT7 Day3) following the UV irradiation. All UV assays were performed in two independent experiments for both species. For N. vectensis, the upper body column was mounted on a slide, and the cells in the epithelium layer (ectodermis) were imaged. For C. andromeda, 2–3 rhopalia were dissected from each animal (11 animals per time point; ZT7, ZT9, ZT7 Day3) and DNA damage was quantified in cells located in the mesogleal surface of the peri-rhopalial tissue adjacent to each rhopalium.

Etoposide treatment in N. vectensis

N. vectensis were habituated for 72 h and entrained to LD cycle in six-well plates. Sleep was recorded during 54 h. At ZT8, half of the animals were treated with 10 μm Etoposide (E1383, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and half with control 0.01% DMSO. To quantify DNA damage, at each time point, Etoposide-treated and control animals were fixed in 4% PFA before (ZT7), 1 h (ZT9), and two days (ZT7 Day3) following the treatment. Etoposide assays were performed in two independent experiments. The upper body column was mounted on a slide, and cells located in the epithelium layer (ectodermis) were imaged.

DNA damage dynamics under LD and SD conditions in C. andromeda and N. vectensis

In both species, animals were habituated in their video monitoring system for 72 h and entrained to an LD cycle. SD was applied as described above. To quantify DNA damage, animals were fixed in 4% PFA at each time point. All LD and SD assays were performed in three independent experiments for both species. For N. vectensis, the upper body column of transgenic tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX)+/- animal was mounted on a slide, and neurons in the epithelium layer (ectodermis) were imaged. DNA damage quantification analyses were performed in mOrangeCAAX-positive neurons at ZT17, ZT8, and ZT17 Day 2. For C. andromeda, 2-4 rhopalia were dissected from each animal (8-10 animals per time point; ZT11, ZT23, and ZT11 Day 2) and DNA damage was quantified in cells located on the mesogleal surface of the peri-rhopalial tissue adjacent to each rhopalium.

Immunohistochemistry assays in C. andromeda and N. vectensis

tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX)+/- and wild type N. vectensis were fixed overnight in 4% PFA in 2XPBS at 4 °C and washed with PBS. The umbrella tissues of C. andromeda surrounding the rhopalium were sampled and fixed for 5 min in 2% PFA in ASW at room temperature, followed by a 6 h fixation in 4% PFA in PBS at 4 °C and washed with PBS. For both species, the tissues were incubated with 2 μg/mL protein kinase (PK) for 10 min, then washed in PBS + 0.1% Triton 3 x 15 min, blocked with 10% fetal bovine serum with 1% DMSO, and diluted in PBS + 0.1% Triton for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, in N. vectensis, tissues were incubated with a primary antibody: rabbit anti-γH2AX (GTX127342, GeneTex, Irvine, CA, USA) 1:200 dilution and antiDsRED (Living Colors® mCherry Monoclonal mouse Antibody, Clontech, Cat# 632543) 1:200 dilution in blocking buffer for 72 h at 4 °C, while in C. andromeda, tissues were incubated with the rabbit anti-γH2AX 1:200 dilution. Then, for both species, samples were washed in PBS + 0.1% Triton 3 x 15 min. N. vectensis were incubated for 1 h with a goat polyclonal secondary anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 646 nm, 2 mg/ml, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488 nm, 2 mg/ml, Invitrogen) and with DAPI at 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer at room temperature. C. andromeda were incubated for 1 h with anti-mouse IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488 nm, 2 mg/ml, Invitrogen) and with DAPI at 1:1000 dilution in blocking buffer at room temperature. Next, both species were washed in PBS + 0.1% Triton 3 x 15 min and the slides were mounted and prepared for imaging and cellular quantification.

Confocal microscope imaging

All imaging experiments were conducted on fixed dissected tissue mounted on slides in glycerol for both species. Imaging was performed using a Zeiss LSM880 inverted and a LSM980 upright confocal/two-photon microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with ×63, 1.4 NA objective. γH2AX puncta were automatically counted using an ImageJ macro code utilizing the Analyze Particles built-in ImageJ plugin (NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, USA), within DAPI-based ROIs to focus on nuclear signal. Between 10-100 cells were analyzed in each C. andromeda rhopalia and N. vectensis. In addition to DAPI and γH2AX signal, a third channel was used to detect the fluorophore mOrange expressed in the nervous system of tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX) N. vectensis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data behind the main and Supplementary Figs. are provided in the GitHib repository https://github.com/amirharduf/FFDB_Sleep. Large raw video datasets are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

Custom codes used for analysis are available on GitHub https://github.com/amirharduf/FFDB_Sleep.

References

Keene, A. C. & Duboue, E. R. The origins and evolution of sleep. J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb159533 (2018).

Anafi, R. C., Kayser, M. S. & Raizen, D. M. Exploring phylogeny to find the function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20, 109–116 (2019).

Kanaya, H. J. et al. A sleep-like state in Hydra unravels conserved sleep mechanisms during the evolutionary development of the central nervous system. Sci. Adv. 6, eabb9415 (2020).

Nath, R. D. et al. The Jellyfish cassiopea exhibits a sleep-like state. Curr. Biol. 27, 2984–2990 (2017).

Pophale, A. et al. Wake-like skin patterning and neural activity during octopus sleep. Nature 619, 129–134 (2023).

Moon, J., Caron, J.-B. & Moysiuk, J. A macroscopic free-swimming medusa from the middle Cambrian Burgess Shale. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 290, 20222490 (2023).

Krause, A. J. et al. The sleep-deprived human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 404–418 (2017).

Vaccaro, A. et al. Sleep loss can cause death through accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the gut. Cell 181, 1307–1328.e15 (2020).

Coulson, R. L., Mourrain, P. & Wang, G. X. Sleep deficiency as a driver of cellular stress and damage in neurological disorders. Sleep. Med Rev. 63, 101616 (2022).

Benington, J. H. & Heller, H. C. Restoration of brain energy metabolism as the function of sleep. Prog. Neurobiol. 45, 347–360 (1995).

Seibt, J. & Frank, M. G. Primed to sleep: the dynamics of synaptic plasticity across brain states. Front Syst. Neurosci. 13, 2 (2019).

Singh, P. & Donlea, J. M. Bidirectional regulation of sleep and synapse pruning after neural injury. Curr. Biol. 30, 1063–1076.e3 (2020).

Thimgan, M. S., Duntley, S. P. & Shaw, P. J. Changes in gene expression with sleep. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 7, S26–S27 (2011).

Ungurean, G., van der Meij, J., Rattenborg, N. C. & Lesku, J. A. Evolution and plasticity of sleep. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 15, 111–119 (2020).

Zada, D. & Appelbaum, L. Chapter 9 - Behavioral criteria and techniques to define sleep in zebrafish. in Behavioral and Neural Genetics of Zebrafish (ed. Gerlai, R. T.) 141–153 (Academic Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-817528-6.00009-7.

Miyazaki, S., Liu, C.-Y. & Hayashi, Y. Sleep in vertebrate and invertebrate animals, and insights into the function and evolution of sleep. Neurosci. Res 118, 3–12 (2017).

Zeitzer, J. M. The neurobiological underpinning of the circadian wake signal. Biochem Pharm. 191, 114386 (2021).

Zada, D., Bronshtein, I., Lerer-Goldshtein, T., Garini, Y. & Appelbaum, L. Sleep increases chromosome dynamics to enable reduction of accumulating DNA damage in single neurons. Nat. Commun. 10, 895 (2019).

Zada, D. et al. Parp1 promotes sleep, which enhances DNA repair in neurons. Mol. Cell 81, 4979–4993 (2021).

Suberbielle, E. et al. Physiologic brain activity causes DNA double-strand breaks in neurons, with exacerbation by amyloid-β. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 613–621 (2013).

Bellesi, M., Bushey, D., Chini, M., Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Contribution of sleep to the repair of neuronal DNA double-strand breaks: evidence from flies and mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 36804 (2016).

Cadet, J. & Wagner, J. R. DNA base damage by reactive oxygen species, oxidizing agents, and UV radiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a012559 (2013).

Lieber, M. R. The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 79, 181–211 (2010).

Arendt, D., Bertucci, P. Y., Achim, K. & Musser, J. M. Evolution of neuronal types and families. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 56, 144–152 (2019).

Watanabe, H., Fujisawa, T. & Holstein, T. W. Cnidarians and the evolutionary origin of the nervous system. Dev. Growth Differ. 51, 167–183 (2009).

Bosch, T. C. G. et al. Back to the basics: cnidarians start to fire. Trends Neurosci. 40, 92–105 (2017).

Nakanishi, N., Renfer, E., Technau, U. & Rentzsch, F. Nervous systems of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis are generated by ectoderm and endoderm and shaped by distinct mechanisms. Development 139, 347–357 (2012).

Sprecher, S. G. Neural cell type diversity in cnidaria. Front Neurosci. 16, 909400 (2022).

Hendricks, W. D., Byrum, C. A. & Meyer-Bernstein, E. L. Characterization of circadian behavior in the starlet sea anemone, Nematostella vectensis. PLoS One 7, e46843 (2012).

Oren, M. et al. Profiling molecular and behavioral circadian rhythms in the non-symbiotic sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Sci. Rep. 5, 11418 (2015).

Ohdera, A. H. et al. Upside-down but headed in the right direction: review of the highly versatile cassiopea xamachana system. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, 35 (2018).

Yang, Y. & Edery, I. Daywake, an anti-siesta gene linked to a splicing-based thermostat from an adjoining clock gene. Curr. Biol. 29, 1728–1734 (2019).

Ashbury, A. M. et al. Wild orangutans maintain sleep homeostasis through napping, counterbalancing socio-ecological factors that interfere with their sleep. SSRN Scholarly Paper at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5131665 (2025).

Aguillon, R. et al. CLOCK evolved in cnidaria to synchronize internal rhythms with diel environmental cues. eLife 12, RP89499 (2024).

Arendt, J. & Aulinas, A. Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin. in Endotext (eds Feingold, K. R. et al.) (MDText.com, Inc., 2000).

Appelbaum, L. et al. Sleep-wake regulation and hypocretin-melatonin interaction in zebrafish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 21942–21947 (2009).

Vivien-Roels, B. & Pévet, P. Melatonin: presence and formation in invertebrates. Experientia 49, 642–647 (1993).

Zhao, D. et al. Melatonin synthesis and function: evolutionary history in animals and plants. Front Endocrinol. 10, 249 (2019).

Turinetto, V. & Giachino, C. Multiple facets of histone variant H2AX: a DNA double-strand-break marker with several biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2489–2498 (2015).

Satterlie, R. A. & Eichinger, J. M. Organization of the ectodermal nervous structures in jellyfish: scyphomedusae. Biol. Bull. 226, 29–40 (2014).

Svanfeldt, K., Lundqvist, L., Rabinowitz, C., Sköld, H. N. & Rinkevich, B. Repair of UV-induced DNA damage in shallow water colonial marine species. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 452, 40–46 (2014).

Ben-Zvi, O., Eyal, G. & Loya, Y. Response of fluorescence morphs of the mesophotic coral Euphyllia paradivisa to ultra-violet radiation. Sci. Rep. 9, 5245 (2019).

Downie, A. T., Cramp, R. L. & Franklin, C. E. The interactive impacts of a constant reef stressor, ultraviolet radiation, with environmental stressors on coral physiology. Sci. Total Environ. 907, 168066 (2024).

Khan, A. Q., Travers, J. B. & Kemp, M. G. Roles of UVA radiation and DNA damage responses in melanoma pathogenesis. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 59, 438–460 (2018).

Lilly, E., Muscala, M., Sharkey, C. R. & McCulloch, K. J. Larval swimming in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis is sensitive to a broad light spectrum and exhibits a wavelength-dependent behavioral switch. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11222 (2024).

Le, T. T. et al. Etoposide promotes DNA loop trapping and barrier formation by topoisomerase II. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 641–650 (2023).

Yamazaki, R. et al. Evolutionary origin of distinct NREM and REM sleep. Front. Psychol. 11, 567618 (2020).

Tainton-Heap, L. A. L. et al. A paradoxical kind of sleep in drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 31, 578–590 (2021).

Leung, L. C. et al. Neural signatures of sleep in zebrafish. Nature 571, 198–204 (2019).

Kremien, M., Shavit, U., Mass, T. & Genin, A. Benefit of pulsation in soft corals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 8978–8983 (2013).

Garm, A., Bielecki, J., Petie, R. & Nilsson, D.-E. Opposite patterns of diurnal activity in the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora and Copula sivickisi. Biol. Bull. 222, 35–45 (2012).

Seymour, J. E., Carrette, T. J. & Sutherland, P. A. Do box jellyfish sleep at night? Med. J. Aust. 181, 707 (2004).

Sorek, M. et al. Setting the pace: host rhythmic behaviour and gene expression patterns in the facultatively symbiotic cnidarian Aiptasia are determined largely by Symbiodinium. Microbiome 6, 83 (2018).

Rattenborg, N. C. Diverse sleep strategies at sea. Science 381, 486–487 (2023).

Rattenborg, N. C. et al. Evidence that birds sleep in mid-flight. Nat. Commun. 7, 12468 (2016).

Gupta, S. C. et al. Chlorpyrifos induces apoptosis and DNA damage in Drosophila through generation of reactive oxygen species. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 73, 1415–1423 (2010).

Rowe, L. A., Degtyareva, N. & Doetsch, P. DNA damage-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 1167–1177 (2008).

Yu, Y., Cui, Y., Niedernhofer, L. & Wang, Y. Occurrence, biological consequences, and human health relevance of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 29, 2008–2039 (2016).

Nugnes, R., Russo, C., Orlo, E., Lavorgna, M. & Isidori, M. Imidacloprid: Comparative toxicity, DNA damage, ROS production and risk assessment for aquatic non-target organisms. Environmental pollution https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2022.120682 (2022).

Maas, A. E., Jones, I. T., Reitzel, A. M. & Tarrant, A. M. Daily cycle in oxygen consumption by the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis Stephenson. Biol. Open 5, 161–164 (2016).

Zhdanova, I. V., Wang, S. Y., Leclair, O. U. & Danilova, N. P. Melatonin promotes sleep-like state in zebrafish. Brain Res. 903, 263–268 (2001).

Omond, S. et al. Inactivity Is nycthemeral, endogenously generated, homeostatically regulated, and melatonin modulated in a free-living platyhelminth flatworm. Sleep 40, 124 (2017).

Kim, P. et al. Melatonin’s role in the timing of sleep onset is conserved in nocturnal mice. npj Biol. Timing Sleep. 1, 13 (2024).

Roopin, M. & Levy, O. Temporal and histological evaluation of melatonin patterns in a ‘basal’ metazoan. J. Pineal Res 53, 259–269 (2012).

Niu, L. et al. Melatonin promotes sleep by activating the BK channel in C. elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 25128–25137 (2020).

Zanif, U. et al. Melatonin supplementation and oxidative DNA damage repair capacity among night shift workers: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Occup Environ Med https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2024-109824 (2025).

Arendt, D. The evolutionary assembly of neuronal machinery. Curr. Biol. 30, R603–R616 (2020).

Kempf, A., Song, S. M., Talbot, C. B. & Miesenböck, G. A potassium channel β-subunit couples mitochondrial electron transport to sleep. Nature 568, 230–234 (2019).

DeBardeleben, H. K., Lopes, L. E., Nessel, M. P. & Raizen, D. M. Stress-Induced Sleep After Exposure to Ultraviolet Light Is Promoted by p53 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 207, 571–582 (2017).

Thé, J. et al. Understanding cassiopea andromeda (Scyphozoa) invasiveness in different habitats: a multiple biomarker comparison. Water 15, 2599 (2023).

Cheung, V., Yuen, V. M., Wong, G. T. C. & Choi, S. W. The effect of sleep deprivation and disruption on DNA damage and health of doctors. Anaesthesia 74, 434–440 (2019).

Botton-Amiot, G., Martinez, P. & Sprecher, S. G. Associative learning in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2220685120 (2023).

Donlea, J. M. Roles for sleep in memory: insights from the fly. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 54, 120–126 (2019).

Bielecki, J., Dam Nielsen, S. K., Nachman, G. & Garm, A. Associative learning in the box jellyfish Tripedalia cystophora. Curr. Biol. 33, 4150–4159.e5 (2023).

Paix, A. et al. Endogenous tagging of multiple cellular components in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2215958120 (2023).

Krueger, J. M., Nguyen, J. T., Dykstra-Aiello, C. J. & Taishi, P. Local sleep. Sleep. Med Rev. 43, 14–21 (2019).

Pregueiro, A. M., Liu, Q., Baker, C. L., Dunlap, J. C. & Loros, J. J. The neurospora checkpoint kinase 2: a regulatory link between the circadian and cell cycles. Science 313, 644–649 (2006).

Liao, Y. & Rust, M. J. The circadian clock ensures successful DNA replication in cyanobacteria. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 118, 516118 (2021).

Gamsby, J. J., Loros, J. J. & Dunlap, J. C. A phylogenetically conserved DNA damage response resets the circadian clock. J. Biol. Rhythms 24, 193–202 (2009).

Oklejewicz, M. et al. Phase resetting of the mammalian circadian clock by DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 18, 286–291 (2008).

Lawley, J. W. et al. Box Jellyfish alatina alata has a circumtropical distribution. Biol. Bull. 231, 152–169 (2016).

Genikhovich, G. & Technau, U. Induction of spawning in the starlet sea anemone Nematostella vectensis, in vitro fertilization of gametes, and dejellying of zygotes. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2009, pdb.prot5281 (2009).

MATLAB. (The MathWorks Inc., 2020).

Ruf, T. The Lomb-Scargle periodogram in biological rhythm research: analysis of incomplete and unequally spaced time-series. Biol. Rhythm Res. 30, 178–201 (1999).

R Core Team. R: a language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Roni Turgeman and Noa Maor for their assistance with N. vectensis maintenance, and Yael Laure for English editing. We thank to Julia Sharabany for technical assistance, and to Gil Koplovitz (IUI, Israel) for donating the C. andromeda picture in the sea. We also thank Prof. Tamar Lotan (University of Haifa, Israel) for donating the tg(-2.4NvElav1b:mOrangeCAAX) N. vectensis, which was generated by the lab of Prof. Fabian Rentzsch (University of Bergen, Norway). We would like to thank the organizers of the 5th Annual International Cassiopea Conference, Key Largo, Florida (2022), and the staff of the Key Largo Marine Research Laboratory for their generous support and for hosting the field experiments. In addition, we thank the team at the Cell and Tissue Imaging Platform - PICT-IBiSA (member of France–Bioimaging -ANR-24-INBS-0005 FBI BIOGEN) of Institut Curie for helping with imaging assays. The research was funded by the German Israeli Foundation Nexus (grant no. G-1566-413.13/2023 to LA and OL), the Israel Science Foundation (ISF, grant no. 961/19 and 1214/24 to LA), and the Moore Foundation (grant no. 4598 to OL). Raphaël Aguillon post-doctoral fellowship was supported by the Azrieli Foundation.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.”

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aguillon, R., Harduf, A., Sagi, D. et al. DNA damage modulates sleep drive in basal cnidarians with divergent chronotypes. Nat Commun 17, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67400-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67400-5