Introduction

Cognitive development is profoundly influenced by rearing conditions. For instance, after Donald O. Hebb’s early discovery that domestic rats performed better in problem-solving tests than rats raised in laboratory cages1, numerous studies have employed environmental enrichment (EE) to study the impact of a stimulating setting on cognitive development2. Prolonged exposure to EE, which typically includes opportunity for physical exercise, exploration of novel objects and increased social interactions, has been shown to improve memory in various hippocampal-dependent tasks both in wild type animals and in a range of models of neuronal dysfunction, including brain injury, Huntington’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease and intellectual disability disorders3,4,5,6,7,8. Investigation of the underlying cellular and synaptic mechanisms revealed that EE stimulates neurogenesis9,10,11 and increases spine density, dendritic length and dendritic complexity in hippocampus and cortex regions3,7,12. Conversely, an impoverished environment (IE), conceived as individual housing with no exposure to stimulating objects, has been used to model psychiatric disorders in rodents13,14,15, and leads to cognitive impairments, decreased dendritic length and spine density, and defects in glutamatergic transmission16,17,18,19.

The application of EE as a potential intervention for a broad range of human traits20,21, from neurodevelopmental disorders in children22 to cognitive decline in the elderly23, has sparked significant interest in understanding the molecular mechanisms by which housing conditions influence cognition. Transcriptional and epigenetic processes, which are well-established mediators between environmental factors and the genome24,25, play a crucial role in synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory26,27,28,29. These mechanisms are therefore appealing candidates for translating the impact of rearing conditions into cognitive outcomes. However, genome-wide studies on cortical and hippocampal neurons following EE have identified relatively few consistent changes in gene expression30,31,32,33. The molecular study of IE has received far less attention, leaving the genomic modifications induced by IE largely unexplored. A comprehensive understanding of the epigenetic and transcriptional programs driving environment-induced changes in neuronal plasticity and behavior could be crucial for developing new therapeutic strategies that mimic EE or correct IE-related deficits. Yet, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Since cellular heterogeneity in nervous tissue may obscure subtle changes induced by environmental conditions, strategies that mitigate cellular heterogeneity would significantly enhance the sensitivity and specificity of epigenomic and transcriptional analyses, offering unprecedented insights.

In this study, we exposed female mice to EE and IE during the juvenile period to investigate how rearing conditions influence cognitive abilities and to map the associated transcriptional and chromatin changes in the two main hippocampal neuron types: CA1 pyramidal and DG granule neurons. Our behavioral experiments revealed opposite and durable effects on the animals’ cognitive abilities, while the multiomic analysis identified activity-regulated AP-1 as a central player, activated by EE and inhibited by IE, leading to the cell type-specific modulation of synaptic target genes critical for memory functions.

Results

Bidirectional regulation of cognitive capacities by rearing conditions

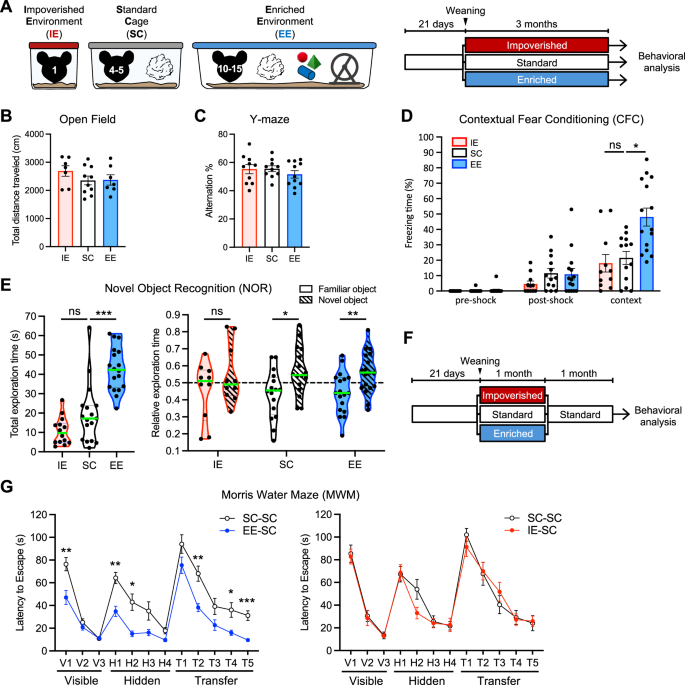

To investigate the impact of EE on cognitive functions, we developed a paradigm in which a large cohort of 3-week-old C57BL6/J female mice was weaned and housed together in an ample space with opportunities for voluntary exercise, social interaction and exploration of novel objects, where toys and running wheels were changed every two weeks. In parallel, to investigate the impact of social isolation and IE, 3-week-old female mice were weaned and housed individually in small cages, shielded from acoustic, visual, and social stimuli. After 3 months, we compared the performance of the EE and IE cohorts and their littermates housed in standard cages (SC; 4-5 mice per cage) (Fig. 1A).

A Experimental design. At weaning (P21), littermate WT female mice were randomly distributed in impoverished (IE, red), standard (SC, white), or enriched (EE, blue) environment for three months before behavioral analysis. B Total distance traveled in the Open Field test. Mean ± SEM is shown. IE, n = 7 mice per group; SC, n = 10; EE, n = 7. No statistically significant differences comparing EE vs SC and IE vs SC by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. C Alternation percentage in the Y-maze. Mean ± SEM is shown. IE, n = 10; SC, n = 10; EE, n = 11. No statistically significant differences comparing EE vs SC and IE vs SC by Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. D. Contextual Fear Conditioning. The freezing time before the shock, after the shock, and during the context session was measured. Mean ± SEM is shown. IE, n = 11; SC, n = 13; EE, n = 15. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test comparing EE vs SC (*p = 0.0111) and IE vs SC (ns, not significant). E Novel Object Recognition. The total time spent exploring the identical objects during the training (left) and the relative time spent exploring the familiar and the novel object during the test session (right) are shown. The green horizontal line across the violin plot represents the median. IE, n = 14; SC, n = 17; EE, n = 18. Mice with a total exploration time inferior to 5 s during the training or the test were excluded from the analysis of the relative exploration time. Total exploration time, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test comparing EE vs SC (***p = 0.0004) and IE vs SC (ns). Relative exploration time, Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test comparing familiar and novel object: IE, ns; SC, *p = 0.0168; EE, **p = 0.0050. F Experimental design. At weaning (P21), littermate female mice were randomly distributed in impoverished (IE-SC, red), standard (SC-SC, white), or enriched (EE-SC, blue) environment for one month, and were then kept in standard environment for one additional month before behavioral analysis. G Morris Water Maze. The latency to reach the platform as an indicator of spatial memory was measured for EE-SC vs SC-SC (left) and IE-SC vs SC-SC (right). Mean ± SEM is shown. EE-SC vs SC-SC: SC-SC, n = 14; EE-SC, n = 15. IE-SC vs SC-SC: SC-SC, n = 10; IE-SC, n = 11. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with the Geisser-Greenhouse correction for multiple comparisons. EE-SC vs SC-SC, visible phase: day, ****p < 0.0001, rearing conditions, ***p = 0.0006. EE-SC vs SC-SC, hidden and transfer phase: day, ****p < 0.0001, rearing conditions, ****p < 0.0001. EE-SC vs SC-SC: V1, **p = 0.0031; H1, **p = 0.0019; H2, **p = 0.0101; T2, **p = 0.0041; T4, *p = 0.0439; T5, ***p = 0.0010. IE-SC vs SC-SC, visible, hidden and transfer phase: day, ****p < 0.0001, rearing conditions, not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

First, we examined mice basal exploratory activity in an open field (OF) test and did not find any significant change either in the total distance traveled, nor in the time spent in the center and the periphery of the arena (Fig. 1B and Supp. Fig. S1A). Exploration of a Y-maze did not reveal significant differences either (Fig. 1C and Supp. Fig. S1B). Long-term memory was analyzed in a contextual fear conditioning (CFC) task in which the mice received a single foot-shock. EE mice froze significantly longer during recall, indicating better contextual memory in line with previous studies6, while IE mice behaved similarly to SC mice (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, training in a Novel Object Recognition (NOR) task revealed that EE mice spent more time exploring the objects, while IE mice displayed a trend towards reduced exploration (Fig. 1E, left). Both SC and EE mice dedicated more time to explore the novel object in the test session, while IE mice could not discriminate between the familiar and novel object, suggesting impaired recognition memory (Fig. 1E, right, and Supp. Fig. S1C).

To evaluate the persistence of cognitive changes induced by rearing conditions, we examined the performance of EE and IE mice after being returned to SC one month prior to behavioral assessment (henceforth referred to as EE-SC, IE-SC and SC-SC) (Fig. 1F). Given that spatial navigation is known to improve following EE5,7,34, we first assessed the mice using the Morris Water Maze (WMW) test. EE-SC mice demonstrated superior learning compared to the SC-SC group, whereas IE-SC mice did not differ significantly from their controls (Fig. 1G and Supp. Fig. S1D). EE-SC and SC-SC mice swam at comparable speed (Supp. Fig. S1E), and rearing conditions did not affect forelimb strength (Supp. Fig. S1F), suggesting that the reduced latency of the EE-SC group likely reflects improved spatial learning rather than enhanced swimming abilities or physical strength. In the CFC task, EE-SC mice also exhibited significantly stronger associative memory compared to their SC-SC littermates, while IE-SC mice performed similarly to the SC-SC group (Supp. Fig. S1G). Similarly, in a working memory task conducted using the radial maze, EE-SC mice outperformed their SC-SC littermates, while IE-SC mice showed a greater number of errors (Supp. Fig. S1H).

In summary, our findings reveal that experiencing IE, and especially EE, during the juvenile period exerts a lasting impact on hippocampal-dependent memory processes, highlighting the potential existence of enduring molecular changes in hippocampal neurons.

CA1 and DG excitatory neurons exhibit distinct transcriptional and chromatin profiles

The chromatin of CA1 pyramidal neurons and DG granule neurons, the two main neuronal populations in the hippocampus with fundamental yet distinct roles in memory formation35,36, are likely depository for environment-induced molecular changes that influences neuronal responsiveness and hippocampal circuits functioning. To investigate if EE and IE trigger changes in the transcriptome and chromatin of these neurons, we generated mice in which the nuclear envelope of forebrain excitatory neurons is fluorescently tagged with the fusion protein SUN1-GFP upon tamoxifen (TMX) injection (Fig. 2A; hereafter referred to as Sun1-GFP mice). This labeling strategy enabled efficient isolation of these neuronal nuclei from CA1 and DG regions through fluorescence-activated nuclear sorting (FANS) (Supp. Fig. S2A) for subsequent transcriptional and epigenomic analyses29.

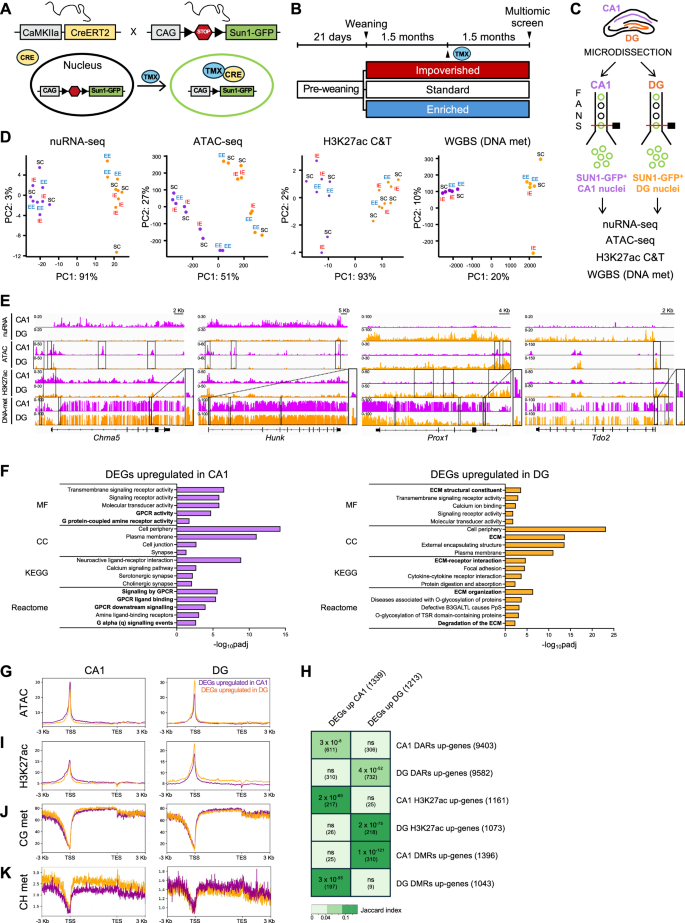

A Genetic strategy for the conditional expression of Sun1-GFP in forebrain excitatory neurons. B At weaning (P21), Sun1-GFP female mice were randomly distributed in enriched (EE, blue), standard (SC, white) or impoverished (IE, red) environment for 3 months. At 1.5 month, mice were administered TMX. C Experimental design. SUN1-GFP+ nuclei were isolated by FANS from manually dissected CA1 and DG regions for downstream multiomic analysis. D PCA of nuRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac CUT&TAG and WGBS DNA methylation profiles of CA1 and DG SUN1-GFP+ neurons. nuRNA-seq, ATAC-seq: n = 3 samples per region per rearing condition. H3K27ac CUT&TAG: CA1 SC, CA1 IE, DG IE, n = 3 samples; CA1 EE, n = 2; DG EE, n = 2; DG SC, n = 4. WGBS DNA methylation: n = 2 samples per region per rearing condition. E Snapshot of nuRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac and DNA methylation genomic profiles of Chrna5, Hunk (CA1 pyramidal neurons markers), Prox1 and Tdo2 (DG granule neurons marker) genes in CA1 (violet) and DG (orange) samples from SC mice. DNA methylation is represented as the percentage of methylation at a given position. DARs, differential H3K27ac peaks and DMRs are highlighted by rectangles. Zoomed-in panels displaying DNA methylation profiles of the boxed regions are shown on the right. F Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the upregulated DEGs in CA1 (left) and DG (right) excitatory neurons. Fisher’s one-tailed test with g: SCS (Set Counts and Sizes) correction for multiple comparisons. The 4-5 significant GO terms with higher -log10padj for Molecular Function (MF), Cellular Component (CC), KEGG pathway and Reactome pathway are shown. The minimum number of genes in a statistically significant GO group is 4, and among those displayed in the figure, it is 10. GO terms related to GPCR signaling and ECM are highlighted in bold for CA1 and DG, respectively. G Density distribution of ATAC reads across the DEGs up-regulated in CA1 and DG. H Matrix illustrating the overlap between the genes significantly up-regulated in CA1 or DG neurons, and the genes associated with DARs, H3K27ac peaks and DMRs significantly increased in CA1 or DG neurons. The Jaccard index and the number of shared genes for each comparison, in brackets, are indicated. I Density distribution of H3K27ac reads across the DEGs up-regulated in CA1 and DG. J,K Percentage of cytosine methylation within CG context (J) and CH context (K) across the DEGs up-regulated in CA1 and DG.

Sun1-GFP mice were housed in IE, SC or EE starting at 3-weeks of age, and after 6 weeks, TMX was administered to trigger SUN1-GFP expression (Fig. 2B). After 6 additional weeks in their respective environments, the mice were euthanized, CA1 and DG hippocampal layers were microdissected, and the tissues dissociated and subjected to FANS for multiomic analysis (Fig. 2C). RT-qPCR assays of specific markers of DG (Tdo2, Dsp) and CA1 (Ccn3)37 confirmed the efficiency and precision of the hippocampal subregions microdissection (Supp. Fig. S2B).

Transcriptional changes were assessed using nuRNA-seq, providing insights into gene expression dynamics. Chromatin accessibility was evaluated through ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin coupled to sequencing), which allowed for the identification of regulatory elements and potential changes in the epigenetic landscape. Histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) was investigated using CUT&TAG38, a targeted approach to detect modifications associated with active enhancers and promoters, linking chromatin state to transcriptional activity. DNA methylation patterns were examined via low-input whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to further identify changes in the epigenetic state influencing gene regulation. This multiomic strategy provided a robust framework for unraveling the interplay between housing conditions, gene expression and chromatin modifications. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed a clear separation between CA1 (violet) and DG (orange) samples in all four genomic screens, while we did not observe any obvious clustering of the samples according to environmental conditions (Fig. 2D).

As a first step in our analyses, we compared CA1 and DG neurons in SC conditions to identify fundamental differences in their transcriptomic and chromatin profiles, before assessing how environmental perturbations modify these cell-type specific programs. nuRNA-seq identified 2552 differentially expressed genes (DEGs; padj <0.05 and ∣log2FC(CA1/DG)∣ > 1), with 1339 genes up-regulated in CA1 and 1,213 genes up-regulated in DG (Supp. Fig. S3A and Supp. Data 1). DEGs included well-known markers of CA1 pyramidal neurons, such as Chrna5 and Hunk, and DG granule neurons, such as Prox1 and Tdo2 (Fig. 2E). GO analysis revealed profound differences between the two neuronal types in terms of cell adhesion molecules and intracellular signaling. In particular, multiple G-protein-coupled (Gprc6A, Gpr101, Gpr139, Gpr26, Gpr161, Gpr3), serotoninergic (Htr1b, Htr2c, Htr5b, Htr1f), and cholinergic (Chrm2, Chrm3, Chrm5, Chrna4) receptors were found up-regulated in CA1 neurons, while extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins were highly overrepresented in DG neurons, including members of laminin (Lama1, Lama2, Lama5), collagen (Col1a1, Col1a2, Col3a1, Col4a5, Col4a6, Col5a3, Col12a1, Col13a1, Col15a1, Col27a1) and ADAMTS (short for a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs) families (Adamts3, Adamts12, Adamts15, Adamts17, Adamts18, Adamtsl2) (Fig. 2F and Supp. Data 2). These broad transcriptomic differences likely underlie the distinct synaptic features and functional specialization of CA1 and DG excitatory neurons35,39.

ATAC-seq peaks were overrepresented in gene bodies and promoters, in line with the association of open chromatin with transcribed genes (Supp. Fig. S3B). Comparative analysis identified 39,084 differentially accessible regions (DARs; padj <0.01 and log2FC(CA1/DG) > 1) between CA1 and DG samples in the SC condition, with 20,465 regions more accessible in CA1 and 18,619 regions more accessible in DG (Supp. Fig. S3D and Supp. Data 3). Chromatin opening is a well-established feature of actively transcribed genes. In agreement, CA1 pyramidal neurons displayed higher accessibility across CA1 up-regulated genes than DG up-regulated genes, and vice versa for DG granule neurons (Fig. 2E, G and Supp. Fig. S3C). Furthermore, the genes annotated to DARs augmented in a specific cell-type showed a highly significant overlap with the DEGs upregulated in the same neuronal type (Fig. 2H).

Similar to ATAC-seq, CUT&Tag profiling of H3K27ac revealed peak enrichment at promoters and gene bodies, consistent with its association with active transcription (Supp. Fig. S3B). When comparing H3K27ac profiles between CA1 SC and DG SC samples, 2426 and 1765 peaks were retrieved as significantly increased in CA1 or DG neurons, respectively (padj <0.05 and log2FC(CA1/DG) > 1) (Supp. Fig. S3E and Supp. Data 4). Like chromatin accessibility, H3K27ac levels at CA1 up-regulated genes were higher than DG up-regulated genes in CA1 pyramidal neurons, and vice versa for DG granule neurons (Fig. 2E, I). Coherently, the genes annotated to H3K27ac peaks that increased in one cell-type largely overlapped with the DEGs upregulated in the same neuronal population (Fig. 2H). Overall, we found widespread changes in chromatin accessibility and H3K27 acetylation between pyramidal and granule neurons, which positively correlate with their cell-type specific transcriptional signatures, consistent with the established association of these chromatin features with active gene expression.

DNA methylation analysis using WGBS revealed even more numerous differences between the two cell types, identifying 91,987 and 82,159 differentially methylated regions (DMRs; FDR < 0.01 and methylation difference > 25%) with higher methylation levels in CA1 and DG neurons, respectively (Supp. Fig. S3F and Supp. Data 5). Promoter DNA methylation is typically associated with gene repression, whereas the effects of gene body methylation on transcription are more complex40. In dividing cells, gene body DNA methylation correlates with gene expression; however, in non-dividing cells such as neurons, it does not correlate with active transcription41,42. We found that genes upregulated in CA1 exhibited regions with lower CG and CH methylation level in the chromatin of CA1 pyramidal neurons across both the promoter and gene body compared to genes upregulated in DG. Conversely, in DG granule neurons, lower DNA methylation levels were observed in the gene bodies of DG-upregulated genes (Fig. 2E, J, K). Consistent with this, and in contrast to genes annotated to ATAC and H3K27ac peaks, the genes associated with DMRs that augmented in one neuronal type significantly overlapped with DEGs upregulated in the other cell type (Fig. 2H). Taken together, our data show that CA1 and DG excitatory neurons exhibit extensive differences in DNA methylation profiles, which inversely correlate with their unique transcriptional programs, indicating a repressive role for this chromatin mark in regulating neuron type-specific gene expression.

To further explore the relationship among chromatin features within each cell type, we categorized differential ATAC-seq peaks between pyramidal and granule neurons as either proximal (<2 kb) or distal (>2 kb) to the nearest TSS and analyzed H3K27ac and DNA methylation profiles across these regions (Supp. Fig. S3G). For all three marks, the profiles were similar between TSS-proximal and -distal regions, suggesting that comparable chromatin processes operate in both contexts. However, we observed marked differences between CA1 and DG neurons in the correlation pattern among chromatin features. In DG neurons, regions with increased chromatin accessibility showed sustained H3K27ac enrichment and reduced DNA methylation, whereas this pattern was much less pronounced in CA1 neurons. These findings suggest a tighter coupling of chromatin features in DG granule neurons than in CA1 pyramidal neurons, pointing to distinct epigenetic mechanisms or greater chromatin heterogeneity in the latter population.

To better understand how the distinct chromatin profiles of CA1 and DG excitatory neurons result into cell-type specific transcriptional programs, we classified all the accessible regions identified by ATAC-seq in the two cell types into promoters or enhancers, based on the presence or absence, respectively, of the epigenetic mark histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) as determined by ChIP-seq analysis of hippocampal excitatory neurons43. Our analysis determined 20,606 promoters and 138,191 enhancers in CA1 pyramidal neurons, and 19,039 promoters and 103,699 enhancers in DG granule neurons (Supp. Fig. S4A). Remarkably, a substantial fraction of promoters and enhancers were exclusive to one cell-type or the other, with 40% of pyramidal neuron enhancers (over 55,000 regions) which were absent in granule neurons, denoting extensive differences in chromatin regulatory landscapes between the two populations (Supp. Fig. S4B). The genes associated to these cell-type exclusive promoters and enhancers largely overlapped with DEGs upregulated in the respective neuronal populations, suggesting that they play a crucial role in shaping the distinct transcriptional profiles of CA1 and DG neurons (Supp. Fig. S4C). Additionally, DMRs with increased DNA methylation in one cell type were enriched in enhancers exclusive to the other, further supporting the repressive role of DNA methylation (Supp. Fig. S4D).

Altogether, our genomic analyses revealed profound differences in the transcriptional and chromatin profiles of the two main neuronal populations in the hippocampus. Furthermore, the strong correlation between transcriptomic and chromatin profiles within each cell population demonstrates the robustness and cell-type specificity of our datasets.

Intrinsic differences in activity-driven transcription between pyramidal and granule neurons

To understand how TFs operate differently in CA1 and DG regulatory regions, we performed a TF footprint analysis of our ATAC-seq dataset within promoters and enhancers shared by CA1 and DG excitatory neurons (p < 0.05 and binding differential score >0.25 or <−0.25). The analysis revealed that the activity-dependent transcriptional complexes AP-1 and NEUROD44,45 exhibited stronger predicted binding to chromatin in pyramidal neurons compared to granule neurons, both within promoters and enhancers (Fig. 3A, B and Supp. Fig. S5A). These results suggest that CA1 neurons exhibit distinct responses to synaptic activation compared to DG neurons, with activity-induced signaling pathways being more strongly activated in CA1 neurons under standard conditions, likely reflecting higher baseline activity in pyramidal neurons.

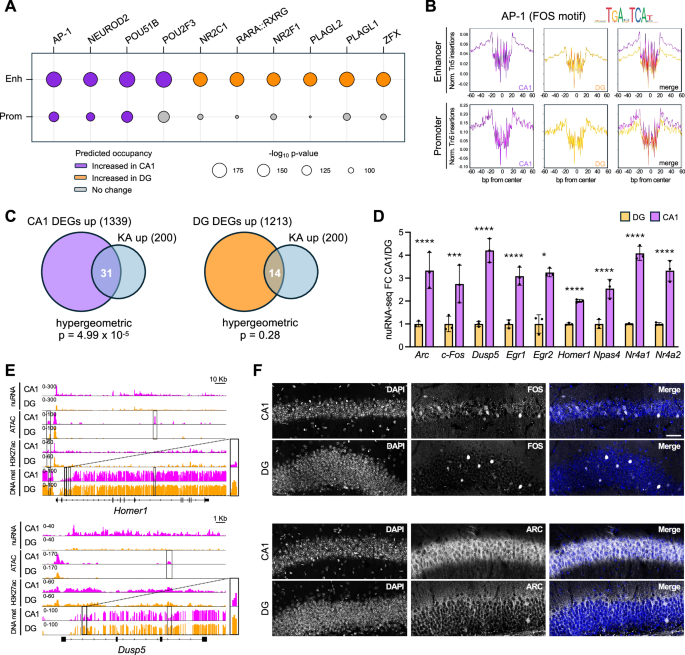

A TF binding prediction in enhancers and promoters comparing CA1 (violet) and DG (orange) excitatory neurons in SC conditions (p < 0.05 and binding differential score >0.25 or <−0.25; significance derived from the TOBIAS model). Circle size indicates motif enrichment p-value, and circle color refers to the predicted occupancy by the TFs. n = 3 samples per region. B Digital footprint for AP-1 (FOS motif) in enhancers (top) and promoters (bottom) comparing CA1 and DG excitatory neurons. Values correspond to normalized Tn5 insertions. C Venn diagrams showing the overlap between the DEGs up-regulated in CA1 (left) or DG (right) excitatory neurons and the 200 most up-regulated genes in response to KA treatment29. Cumulative hypergeometric probability is indicated. D Relative expression levels of a panel of IEGs in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons in SC conditions, as measured by nuRNA-seq. Data are expressed as fold change over DG neurons levels. Mean ± SD is shown. n = 3 samples per region. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test: Arc, Dusp5, Egr1, Homer1, Npas4, Nr4a1, Nr4a2 ****padj <0.0001; Fos, ***padj = 0.0003; Egr2, *padj = 0.0150. E Snapshot of nuRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac and DNA methylation genomic profiles of Homer1 (top) and Dusp5 (bottom) genes in CA1 (violet) and DG (orange) samples from SC mice. DNA methylation is represented as the percentage of methylation at a given position. DARs, differential H3K27ac peaks and DMRs are highlighted by rectangles. Zoomed-in panels displaying DNA methylation profiles of the boxed regions are shown on the right. F Representative immunostaining of FOS (top) and ARC (bottom) proteins in CA1 and DG coronal sections of SC mice. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 40 µm. The staining was repeated on n = 2 mice. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further investigate the regulation of activity-induced gene expression in the two cell types, we examined the levels of previously identified activity-induced genes29 within our datasets. Interestingly, a significant fraction of the top 200 induced genes was upregulated in CA1 neurons compared to DG neurons in SC (Fig. 3C), including classical inmediate early genes (IEGs) such as Arc, Fos, Dusp5, Egr1, Egr2, Homer1, Npas4, Nr4a1 and Nr4a2 (Fig. 3D). Some of these genes also displayed higher accessibility, increased H3K27ac levels and reduced DNA methylation in CA1 compared to DG (e.g., Homer1 and Dusp5, Fig. 3E). Since IEGs are induced in response to neuronal activity, our results suggest that a larger fraction of CA1 neurons are active in standard housing conditions compared to DG neurons.

Consistent with the multiomic analysis, immunostaining of hippocampal sections revealed a moderate but spread expression of FOS protein in CA1 pyramidal neurons, while only a few sparse granule neurons in the DG layer displayed detectable FOS levels (Fig. 3F, top). Similarly, ARC showed a stronger expression in CA1 compared to DG (Fig. 3F, bottom).

These findings align with differences observed during flow cytometry. While DG nuclei showed a narrow green fluorescence distribution across all conditions, CA1 SC samples displayed a bimodal signal distribution, which was shifted toward higher levels after EE (Supp. Fig. S6A, B). Sun1-GFP expression is driven by the chimeric CAG promoter that contains binding sites for activity-regulated transcription factors (TFs) like the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) and the activator protein 1 (AP-1)46. Consistently, Sun1-GFP transcripts were significantly increased in animals treated with the glutamate receptor agonist kainic acid (KA) compared to saline29 (Supp. Fig. S6C). Altogether, these results suggest that CA1 pyramidal neurons have a more sustained baseline activity than DG granule neurons, and that EE causes an increase in tonic activity-dependent transcription in CA1 neurons.

EE enhances and IE downregulates the activity-induced transcriptional program in hippocampal neurons

Next, we conducted a detailed analysis of the transcriptional and chromatin differences induced by rearing conditions in the two cell types. In the PCA of CA1 nuRNA-seq samples, the experimental groups did not cluster distinctly, although IE nuclei tended to separate from the other two conditions (Fig. 4A). Indeed, IE was the primary driver of the transcriptional changes, leading to the downregulation of most DEGs (Fig. 4B). Notably, nearly all DEGs were more strongly expressed in CA1 than DG in standard conditions. We identified 58 DEGs (padj <0.1; Supp. Data 6) which displayed a highly significant number of physical and functional interactions among them, including a group of 6 highly interconnected IEGs involved in transcriptional regulation (Supp. Fig. S7A). Remarkably, we noticed that numerous IEGs (Arc, Fos, Fosb, Egr1, Egr2, Npas4, 1700016p03rik) clustered together and were downregulated after IE and upregulated in response to EE (Fig. 4B, C). Consistent with flow cytometry findings, this evidence indicates that rearing conditions bidirectionally regulate the activity-dependent transcriptional program in CA1 pyramidal neurons.

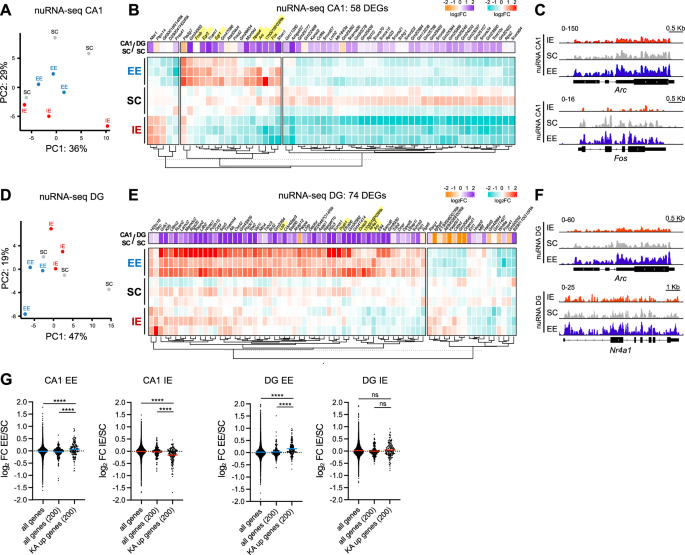

A PCA of nuRNA-seq profiles of CA1 neurons in IE, SC an EE conditions (n = 3 samples per rearing condition). B Heatmap of DEGs in nuRNA-seq profiles of CA1 neurons in IE, SC and EE conditions (LRT test, padj <0.1). The gene expression fold change of each gene in the CA1 SC vs DG SC comparison (Fig. 2) is also shown. IEGs are highlighted in yellow. C Snapshot of nuRNA-seq genomic profiles of Arc and Fos in CA1 samples in IE (red), SC (gray) and EE (blue) conditions. The merged profiles of three independent samples are shown. D PCA of nuRNA-seq profiles of DG neurons in IE, SC an EE conditions (n = 3 samples per rearing condition). E Heatmap of DEGs in nuRNA-seq profiles of DG neurons in IE, SC and EE conditions (LRT test, padj <0.1). The gene expression fold change of each gene in the CA1 SC vs DG SC comparison is also shown. IEGs are highlighted in yellow. F Snapshot of nuRNA-seq genomic profiles of Arc and Nr4a1 genes in DG samples in IE (red), SC (gray) and EE (blue) conditions. The merged profiles of three independent samples are shown. G The effect of EE and IE on the expression levels of the top 200 KA-induced genes in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons is shown. The log2FC of all detected genes and a randomly selected subset of 200 genes are also plotted as controls. The horizontal line across the violin plot represents the median. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test, ****p < 0.0001, ns not significant. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In DG granule neurons, PCA revealed slight segregation of EE samples, while IE and SC samples were intermingled (Fig. 4D). In agreement with this pattern, IE and SC displayed similar expression levels among the 74 DEGs identified (padj <0.1; Supp. Data 6 and Supp. Fig. S7B), while EE was responsible for most transcriptional changes, leading to the upregulation of the majority of the DEGs (Fig. 4E). Almost all DEGs were enriched in CA1 compared to DG, suggesting that EE induces a subset of the CA1 transcriptional program in DG granule neurons (Fig. 4E). Of the 74 DEGs identified in DG, only three overlapped with the DEGs in CA1, indicating that rearing conditions modulate distinct gene sets in pyramidal and granule neurons. However, we retrieved multiple IEGs (Arc, Nr4a1, Dusp5, Pcsk1, Lbh, 1700016p03rik) upregulated under the EE condition (Fig. 4E, F), demonstrating that EE enhances the activity-driven transcriptional program also in the DG.

Next, to analyze the global behavior of the activity-induced transcriptional program in response to environmental conditions, we examined the EE/SC and IE/SC fold-change of the 200 genes most strongly induced by KA in the hippocampus29. Remarkably, EE led to a significant up-regulation of the activity-induced gene program both in CA1 and in DG, while IE robustly downregulated this set of genes in the CA1 but had no apparent effect in the DG (Fig. 4G). In agreement, GSEA analysis of KA-induced genes revealed a strong enrichment of this gene set in EE compared to SC both for CA1 and DG neurons, and an enrichment in SC compared to IE exclusively in CA1 neurons (Supp. Fig. S7C). We also compared our nuRNA-seq data with four published transcriptomic profiles of different brain regions in response to EE (Supp. Fig. S7D)30,31,32,33. Most of the shared genes were IEGs, with Fosb being identified as an upregulated DEG in all the studies considered. Collectively, these findings strongly indicate that EE condition stimulates the activity-dependent transcriptional program in hippocampal excitatory neurons.

Altogether, our nuRNA-seq approach revealed that IE and EE exert opposite and cell-type specific effects on the transcriptional profiles of CA1 and DG excitatory neurons. While IE predominantly drives gene repression in CA1 pyramidal neurons, EE primarily promotes gene expression in DG granule neurons and, to a lesser degree, in CA1 pyramidal neurons, leading to the opposing modulation of activity-dependent genes in both cell types.

EE increases chromatin accessibility and modulates DNA methylation in a subset of granule neuron enhancers

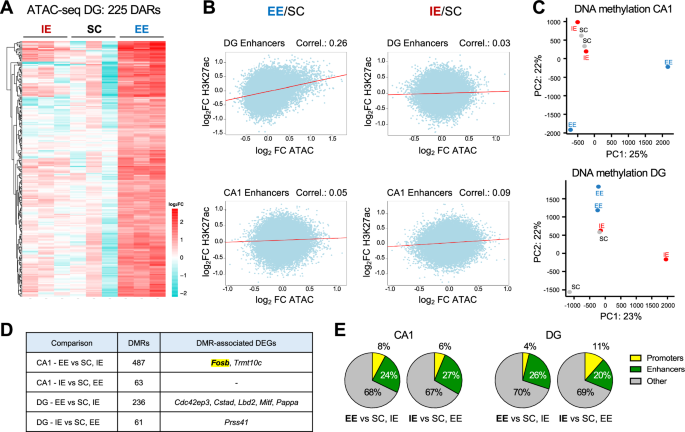

Regarding chromatin accessibility, our ATAC-seq analysis did not uncover any differentially accessible regions (DARs) among the three housing conditions in the CA1 samples, indicating that exposure to the different environments did not trigger strong changes in the chromatin of CA1 pyramidal neurons (Supp. Fig. S8A, left). Conversely, 225 DARs with increased accessibility in EE compared to SC and IE were identified in DG granule neurons (Fig. 5A, Supp. Fig. S8A, right, and Supp. Data 7). This finding is consistent with the evidence that most DEGs in DG neurons were up-regulated under EE (Fig. 4E). Notably, 221 out of 225 DARs were classified as enhancers in DG neurons. Since enhancers can regulate gene expression through long range interactions with promoters, this may account for the small overlap (three genes: Etl4, Ext1 and Asap1) between DEGs and the genes closest to the DARs.

A Heatmap of DARs in ATAC-seq profiles of DG SUN1-GFP+ neurons in IE, SC and EE conditions (padj <0.1). n = 3 samples per rearing condition. B Pearson correlation between the fold change in chromatin accessibility and the fold change in H3K27ac levels when comparing EE vs SC (left) and IE vs SC (right), within DG (top) and CA1 (bottom) excitatory neurons enhancers. C PCA of DNA methylation profiles of CA1 (top) and DG (bottom) SUN1-GFP+ neurons in IE, SC an EE conditions. n = 2 samples per region per rearing condition. D The number of DMRs and the associated DEGs for each comparison are shown. E Pie charts representing the fraction of DMRs overlapping with CA1 and DG promoters and enhancers for each comparison. DMRs not overlapping with either were classified as “others”.

In terms of histone acetylation, our analyses indicate that rearing conditions do not significantly affect H3K27ac profiles in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons. PCA of H3K27ac profiles obtained by CUT&TAG did not reveal a clear separation of the samples according to rearing conditions (Supp. Fig. S8B), and peak calling analysis did not identify any differential peak between environmental conditions for either of the hippocampal layers. We, however, found a positive correlation between the EE-induced changes in chromatin accessibility and H3K27ac levels within DG enhancers, but not when analyzing the IE-induced changes (Fig. 5B). This suggests that a gain in H3K27 acetylation accompanies the increase in enhancers accessibility triggered by EE in DG granule neurons.

Finally, PCA of DNA methylation profiles revealed that EE samples separated from IE and SC samples both in CA1 and DG neurons, suggesting that EE has a more pronounced impact on DNA methylation profiles (Fig. 5C). An initial screen comparing all three conditions identified a few hundred differential methylated regions (DMRs) between EE and SC, and fewer DMRs in the comparison of EI and SC, consistent with the PCA results (Supp. Fig. S8C and Supp. Data 8). To better highlight methylation changes associated with EE, we next compared EE with the pooled IE and SC samples, identifying 487 and 236 DMRs in CA1 and DG, respectively. Only ~60 DMRs were found when comparing IE against the combined SC and EE samples in both CA1 and DG (Fig. 5D and Supp. Data 8). Over 30% of the DMRs were found in promoters or enhancers, suggesting that the DNA methylation changes triggered by rearing conditions might affect gene regulation (Fig. 5E). However, like for DARs, the overlap between DMR-associated genes and DEGs was restricted to a few genes (Fig. 5D and Supp. Data 8). Remarkably, among these hits we identified a DMR located 6.7 kb upstream of Fosb gene in the chromatin of CA1 neurons, which showed lower DNA methylation levels after EE (Supp. Fig. S8D). Given the established role of promoter DNA methylation in gene repression, the DMR located in close proximity of Fosb TSS might potentially contribute to Fosb upregulation in CA1 neurons in response to EE.

In conclusion, our epigenetic study showed that EE increases the accessibility of a restricted subset of enhancers specifically in DG granule neurons and modifies DNA methylation profiles in regulatory regions of CA1 and DG excitatory neurons, including the Fosb promoter. In contrast, IE had reduced effects on chromatin occupancy and DNA methylation in both cell types.

EE and IE opposingly modulate AP-1 activity and its downstream program in a cell-type specific manner

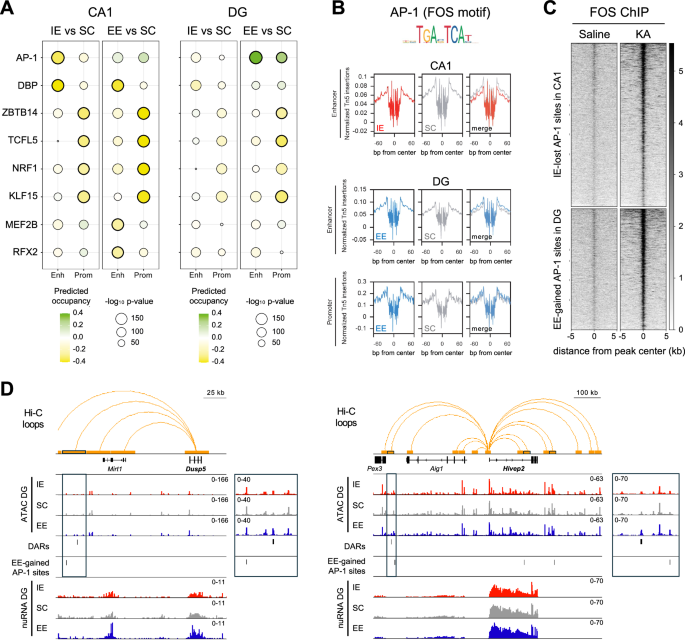

We next investigated whether rearing conditions alter chromatin occupancy by TFs in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons through footprinting analysis of our ATAC-seq dataset. Remarkably, in pyramidal neurons our screen revealed a decreased binding of the activity-induced AP-1 transcriptional complex at enhancer regions in the IE condition compared to SC (Fig. 6A, left, and Fig. 6B, top). Notably, we found 1676 enhancer regions predicted to be bound by AP-1 exclusively in SC, and not in IE. Since AP-1 regulates the transcription of key synaptic genes required for memory processes47,48, the reduced binding of AP-1 to CA1 enhancers regions in IE conditions might underlie the cognitive deficits associated with IE rearing. Importantly, we empirically confirmed that AP-1 binds at these genomic sites upon neuronal activation by performing ChIP-seq against FOS in hippocampal chromatin of mice treated with KA (Fig. 6C). Additionally, we also detected a decrease in Myocyte-enhancing factor 2 (MEF2) binding at enhancer regions after EE (Fig. 6A, left). MEF2 proteins are a family of evolutionarily conserved TFs with a distinctive role as memory constrainers49,50. Thus, the EE-induced decrease of MEF2 occupancy at CA1 enhancer regions might contribute to the cognitive improvement observed in EE-reared mice.

A TF binding prediction in enhancers and promoters comparing EE vs SC and IE vs SC in CA1 (left) and DG (right) excitatory neurons. The two TFs with the strongest binding change for each comparison are shown (p < 0.05 and binding differential score > 0.25 or < −0.25; significance derived from the TOBIAS model). Circle size indicates motif enrichment p-value, and circle color refers to the predicted occupancy by the TFs. Thick borders indicate statistical significance. n = 3 samples per region per rearing condition. B Digital footprint for AP-1 (FOS motif) in CA1 neuron enhancers comparing IE and SC (top) and in DG neuron enhancers and promoters (bottom) comparing EE and SC. Values correspond to normalized Tn5 insertions. C FOS ChIP-seq was performed on hippocampal chromatin obtained from mice treated with saline or KA 1 h. n = 3 mice per group. The heatmaps shows the read density in IE-lost AP-1 sites in CA1 enhancer regions and in EE-gained AP-1 sites in DG enhancer regions. D Hi-C contacts formed by DG DEGs Dusp5 and Hivep2 with regions showing environment-induced chromatin changes. The 25 kb regions containing DARs or EE-gained AP-1 binding sites are outlined with thicker borders. Merged nuRNA-seq and ATAC-seq profiles from three independent DG samples under IE (red), SC (gray) and EE (blue) conditions are also shown. Zoom-in panels display ATAC-seq profiles at the regions marked by rectangles.

In granule neurons, footprint analysis revealed an enrichment of AP-1 binding in both promoters and enhancers of DG neurons from EE mice (Fig. 6A, right, and Fig. 6B, bottom). In particular, 1,242 regions located in DG enhancers are occupied by AP-1 exclusively in the EE condition. FOS ChIP-seq validated these regions as bound by AP-1 after neuronal activation (Fig. 6C).

Taken together, our footprint analyses indicate that rearing the animals in EE stimulates AP-1 DNA-binding activity in DG granule cells, while IE condition leads to reduced AP-1 signaling in CA1 pyramidal neurons. Given the key role of AP-1 in the transcriptional control of synaptic genes, these results suggest that the beneficial and detrimental effects of EE and IE conditions, respectively, on memory capacities might rely on the opposite modulation of AP-1 activity by rearing conditions.

To test whether environmentally induced changes in AP-1 occupancy at enhancers could contribute to differential gene expression, we annotated the AP-1 binding sites with altered AP-1 occupancy to their closest gene. In CA1, the 1676 enhancers, which lose AP-1 binding with IE were linked to 1481 genes, while in DG, the 1242 enhancers which gained AP-1 occupancy under EE were annotated to 1092 genes. While only one CA1 DEG was associated to AP-1-losing enhancers, 10 of the 74 DG DEGs (hypergeometric p-value = 0.0098) were annotated to enhancers gaining AP-1 occupancy in DG neurons, further highlighting the role of AP-1 in regulating EE-driven gene expression in granule neurons.

To explore more deeply the regulatory impact of environment-induced chromatin changes, we leveraged a Hi-C dataset from hippocampal excitatory neurons29 to identify long-range interactions between DEGs and regions harboring chromatin alterations. We found that DG DEGs engaged in 470 chromatin loops, 16 of which contacted regions with DARs, DMRs, or AP-1-enriched enhancers under EE. Similarly, CA1 DEGs formed 243 loops, with five contacting regions bearing environment-induced epigenetic changes. Representative examples of such long-range interactions are illustrated in Fig. 6D. Overall, we could link approximately 30% of DG DEGs and 15% of CA1 DEGs to chromatin alterations, either through direct overlap, or via distal interactions (Supp. Fig. S8E and Supp. Data 9), supporting that epigenetic mechanisms contribute to gene expression regulation in response to environmental conditions.

Fos is required for EE-induced cognitive enhancement

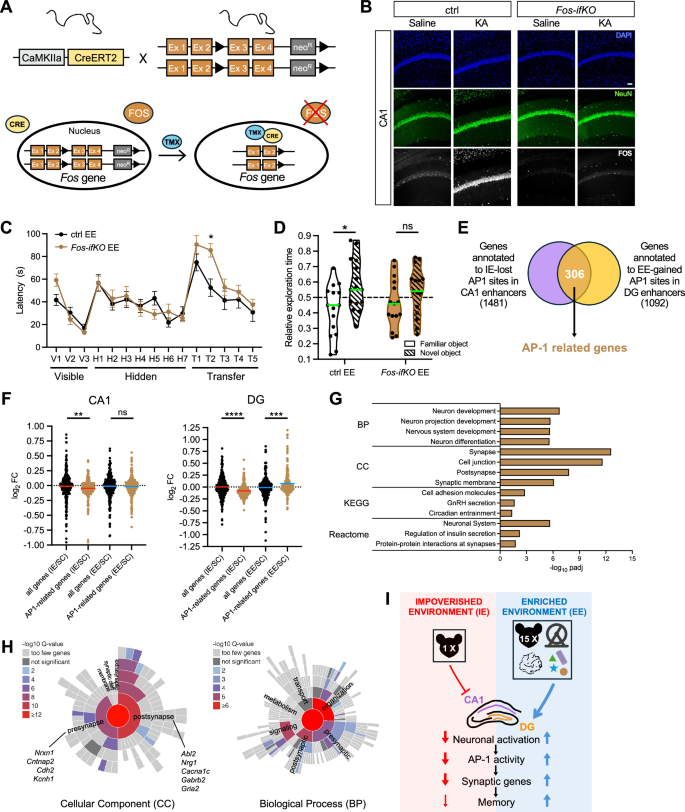

To test whether the AP-1 component FOS is required for mediating the environmental effects on cognition, we generated inducible, forebrain-specific knockout mice in which Fos is conditionally ablated in excitatory neurons (Fosf/f x pCamKIIα-CreERT2 mice administered with tamoxifen, hereafter referred to as Fos-ifKO mice) (Fig. 7A), and tested their performance in the MWM after EE rearing. Previous research has shown that mice lacking neuronal Fos can learn to localize the hidden platform in the MWM as efficiently as controls51. Also, multiple laboratories, including ours, have shown that EE improves spatial navigation in the MWM5,6,7,34 (Fig. 1G). However, the interaction between Fos deficiency and EE has not been tackled.

A Genetic strategy for the conditional ablation of Fos gene in forebrain excitatory neurons. B Representative immunostaining of FOS protein in CA1 coronal sections from control and Fos-ifKO mice treated with saline or KA 1 h. Neuronal nuclei were identified by NeuN staining. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. Scale bar, 50 µm. n = 2 mice per group. C Morris Water Maze. The latency to reach the platform was measured for EE-raised ctrl and Fos ifKO mice. Mean ± SEM is shown. n = 14 mice per group. Repeated measures two-way ANOVA with the Geisser-Greenhouse correction for multiple comparisons. Visible and hidden phase: day, ****p < 0.0001, genotype not significant. Transfer phase: day, ****p < 0.0001, genotype, p = 0.0575, R2, *p = 0.0114. D Novel Object Recognition. The relative time spent exploring the familiar and the novel object are shown. The green horizontal line across the violin plot represents the median. n = 15 mice per group. Two-tailed Mann-Whitney test comparing familiar vs novel object: ctrl EE, *p < 0.0202; Fos ifKO EE, ns. E Venn diagrams showing the overlap between the genes annotated to the IE-lost AP-1 sites in CA1 enhancers (violet), and the genes annotated to the EE-gained AP-1 sites in DG enhancers (orange). F The effect of EE and IE on the expression levels of the 306 AP-1 related genes in CA1 (left) and DG (right) excitatory neurons is shown. The fold change of a same-sized randomly selected subset of genes is plotted as a control. The horizontal line across the violin plot represents the median. n = 3 samples per rearing condition. Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. CA1 IE/SC, **p = 0.0080; CA1 EE/SC, ns, not significant; DG IE/SC, ****p < 0.0001; DG EE/SC, ***p = 0.0004. G GO enrichment analysis of the 306 AP-1 related genes. Fisher’s one-tailed test with g: SCS (Set Counts and Sizes) correction for multiple comparisons, padj <0.05. The 3-4 significant GO terms with higher -log10padj for Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), KEGG pathway and Reactome pathway are shown. The minimum number of genes in a statistically significant GO group is 5, and among those displayed in the figure, it is 7. H SynGO analysis of Cellular Component (left) and Biological Process (right) for the 306 AP-1 related genes. Fisher’s one-tailed test with False Discovery Rate correction for multiple comparisons, q-value < 0.01. The minimum number of genes in a statistically significant group is 3. Examples of genes which have associated with defects in learning and memory or to ASD (SFARI database) are shown. I Working model. EE and IE opposingly modulate the activity-dependent AP-1 pathway in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons in a cell-type specific manner, leading to the transcriptional regulation of AP-1 target genes critical for synaptic function and plasticity, and thus contributing to the opposite effects of EE and IE on memory abilities. The relatively milder impact of IE compared to EE is represented by thinner arrows in the model. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Efficient Fos knock-out in the large majority of CA1 and DG neurons was confirmed by RT-qPCR and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 7B and Supp. Fig. S9A, B). Female Fos-ifKO mice were housed in EE conditions during the first 3 months after weaning, before testing their cognitive abilities in the MWM task. Female littermates lacking the CreERT2 transgene, and thus retaining Fos expression after tamoxifen injections were also reared in EE cages and served as control. Fos deletion did not prevent mice from learning the task, although it significantly affected performance during the transfer phase. Fos-ifKO mice matched control performance in visible and hidden phases but showed longer latencies after platform relocation, indicating reduced cognitive flexibility under EE conditions (Fig. 7C and Supp. Fig. S9C, D). Additionally, Fos-ifKO animals showed a modest but significant memory impairment in the NOR assay compared to controls (Fig. 7D and Supp. Fig. S9E). These results support the conclusion that the AP-1 complex plays a role in mediating the beneficial effect of EE on cognitive abilities.

AP-1 contributes to the regulation of a second wave of activity-driven transcription, affecting genes encoding synaptic effector proteins45. To identify candidate target genes which might mediate AP-1 effect on memory capacities, we focused on the genes annotated to CA1 enhancers that lose AP-1 occupancy after IE, and to DG enhancers, which gain AP-1 binding under EE, as determined in our footprint analysis. The intersection of these two gene sets identified 306 genes associated to enhancers whose AP-1 occupancy is strongly sensitive to environmental conditions, both in CA1 and in DG neurons (Fig. 7E and Supp. Data 10). Remarkably, the average expression of these 306 AP-1-related genes was decreased by IE both in CA1 and in DG neurons and increased by EE in DG neurons (Fig. 7F), suggesting that AP-1 binding at enhancers contributes to transcriptional regulation in response to environmental conditions. These AP-1-related genes significantly overlap with AP-1-regulated genes identified in the triple conditional knockout mouse of Fos, Fosb and Junb in response to kainate treatment52 (Supp. Fig. S9F), which further supports their classification as AP-1-regulated genes. GO analysis of the 306 AP-1 related genes revealed significant enrichment in multiple terms related to synapses (Fig. 7G), with over one fifth of the genes annotated as synaptic genes in the manually curated SynGO database (Fig. 7H and Supp. Data 10). Network analysis using STRING53 (enrichment p-value < 10−16) indicated that the proteins coded by AP-1-related genes exhibited physical or functional interactions significantly higher than chance, supporting the hypothesis that they participate in common synaptic processes.

Genetic alterations in numerous AP-1-regulated genes have been associated with defects in learning and memory in both human and animal studies, such as Csmd154, Cacna1c55, Cntnap256, Nrxn157, Abl258, Nrg159, and Mef2c49,50. Remarkably, according to the SFARI database60, 64 of the 306 AP-1 related genes have been associated to autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (Supp. Data 10), suggesting that rearing conditions may influence the expression of genes critical for intellectual and social abilities through AP-1 signaling.

These findings underscore the critical role of AP-1 bridging environmental influences during the juvenile period to transcriptional regulation of synaptic genes and highlight potential therapeutic targets for enhancing cognitive function and addressing neurodevelopmental disorders.

Discussion

Our experiments demonstrate that rearing mice in EE or IE during the juvenile period has lasting effects on cognitive function. Several weeks after being returned to standard cages, EE-SC mice continued to exhibit improved associative learning and spatial memory, indicating a persistent impact of early-life exposure to EE. Components of enrichment, such as social interaction, voluntary exercise, and object stimulation, have each been shown to independently influence cognitive performance61,62,63. While our study was designed to evaluate their combined effect, future work could dissect the specific contribution of each factor.

Conversely, IE and IE-SC mice performed worse than their respective control littermates in several tasks but showed overall a more limited and task-specific impact on cognitive functions. This aligns with previous studies reporting variable effects of early-life social isolation on learning and memory64,65,66,67. The limited effect of IE could be attributed to the fact that SC is already a relatively impoverished environment. While EE provides increased exploration, novelty, physical activity and social interactions, IE differs from SC mainly in the absence of social contacts. Thus, behavioral differences between IE and SC are likely to be less pronounced than between EE and SC.

It is also important to note that our study was conducted exclusively in female mice, as frequent aggressive encounters among males in the EE condition or in regrouped mice after social isolation (IE-SC group) posed a potential confound. In addition, restricting the study to a single sex reduced inter-individual variability and increased our ability to detect subtle environment-driven effects. Fluctuations in sex hormone levels are known to dynamically influence chromatin accessibility and synaptic gene expression in the hippocampus68, impacting hippocampal structure69, spine density70, neurotransmission71, and associated cognitive functions72. Since estrogenic cycle stage was not monitored in our mice cohorts, we cannot exclude its contribution to the variability in molecular and behavioural outcomes. Furthermore, potential interactions with tamoxifen—a selective estrogen receptor modulator known to affect neuronal gene expression (86)73—may have introduced a minor additional source of variability. Future studies using male mice will help determine the extent to which the mechanisms described are sex-specific.

What underlies the long-lasting behavioural effects of rearing conditions at the molecular level? In this study, we purified the nuclei of hippocampal excitatory neurons from female mice housed in EE, IE, and standard conditions and profiled their transcriptional and epigenetic signatures to identify molecular changes underlying the effects of early post-weaning environmental conditions on cognitive functions. Our multiomic analysis identified a set of synaptic genes regulated by the transcription factor AP-1 in CA1 and DG excitatory neurons in response to housing conditions. Notably, EE enhanced, whereas IE suppressed, neuronal activation and downstream AP-1 pathway activity in a cell-type-specific manner. This differential regulation of AP-1 target genes, critical for synaptic function and plasticity, contributes to the opposing effects of EE and IE on cognitive abilities (Fig. 7I).

Cell type-specific transcriptional and chromatin signatures of rearing conditions

While previous studies highlighted gene expression differences in pyramidal and granule neurons37, our work provides a comprehensive and integrated analysis of transcriptional and epigenetic profiles in these two important neuronal populations. Comparison of CA1 and DG samples from control mice revealed significant and correlated differences in gene expression, chromatin accessibility, histone acetylation, and DNA methylation between these two neuronal types. The distinct chromatin profiles confer each neuronal type with a unique set of enhancers, which shapes its specific transcriptome. These datasets serve as a valuable resource for the neuroscience community, enabling the computational deconvolution of whole-hippocampus genomic data.

Notably, CA1 neurons exhibited higher expression of activity-dependent transcriptional programs compared to DG neurons. This aligns with the evidence that activity-driven gene expression is cell-type specific74,75,76,77, and with the different basal expression levels of IEGs such as Arc and Fos observed across hippocampal layers (Fig. 3F, see also refs. 78,79), reflecting the higher tonic activity of CA1 neurons relative to sparsely active DG neurons. These differences in gene expression likely contribute to the distinct activation dynamics, plasticity mechanisms, and mnemonic functions of pyramidal and granule cells. CA1 pyramidal neurons are highly excitable, with lower action potential thresholds, higher firing rates, and a well-defined afterhyperpolarization (AHP) that supports spike-frequency adaptation. In contrast, DG granule neurons, which exhibit higher input resistance, lower excitability, and require stronger inputs to reach firing thresholds35,39,80, generate sparse and temporally precise spiking that is critical for pattern separation and filtering noisy inputs81,82. These differences underscore the complementary roles of CA1 and DG neurons in hippocampal circuits, with environmental conditions during rearing further amplifying these distinguishing features.

Gene sets regulated by EE and IE were largely distinct in CA1 and DG neurons. DG granule neurons responded primarily to EE, which promoted gene expression, while CA1 pyramidal neurons were more sensitive to IE, which induced gene repression. Moreover, our nuRNA-seq screen revealed bidirectional modulation of activity-dependent gene programs: EE enhanced IEG expression in both DG and CA1, whereas IE suppressed IEG expression in CA1. Chromatin configuration also differed between the conditions. EE increased chromatin accessibility in a subset of DG enhancers, while IE had negligible effects. Additionally, EE induced hundreds of DMRs in both CA1 and DG neurons, with over 30% located in promoters or enhancers, suggesting roles in gene regulation and aligning with previous reports of EE-driven DNA methylation changes in hippocampal neuronal genes83. However, we observed limited overlap between DEGs and genes near DARs or DMRs. One possible explanation is that these epigenetic modifications establish a permissive or primed chromatin state at regulatory elements, influencing the transcriptional responsiveness of target genes to future stimuli, rather than altering their basal expression. In addition, enhancers bearing such chromatin changes could regulate distant genes through long-range genomic interactions. In line with this hypothesis, integration of our datasets with Hi-C data from hippocampal excitatory neurons revealed multiple chromatin loops connecting chromatin changes with DEGs, supporting a potential role of epigenetic mechanisms in shaping gene expression through long-range interactions in response to rearing conditions.

Changes in AP-1 activity reflect neuroadaptation to rearing conditions

Our cell-type specific multiomic analysis identified only a few hundred genes and regulatory regions affected by housing conditions during the juvenile period, consistent with previous studies showing that EE impacts specific loci32,33. Several biological factors and methodological limitations may underlie the modest number of environment-induced molecular changes we identified. First, based on our observation that EE and IE modulate activity-dependent transcriptional programs, environment-induced molecular changes might occur predominantly in discrete ensembles of activated hippocampal neurons. These subtler, ensemble-specific changes are likely masked in bulk analyses of the entire excitatory neuron population. Second, whereas the separation of pyramidal and granule neurons has likely improved the resolution of our screening compared to previous studies, we did not account for gene expression heterogeneity across the dorsoventral axes of the hippocampus37, which might have masked subtle differences. Third, it is worth emphasizing that we assessed long-term genomic changes resulting from a prolonged, non-pharmacological intervention, during which animals had ample time for neuroadaptation along individual trajectories. Consistent with this view, previous studies reported that exposure to EE increases inter-individual variability11,84.

Despite these limitations, our analysis identified the activity-dependent TF AP-1 and its downstream transcriptional network as the primary signaling axis responding to rearing conditions in hippocampal neurons. Multiple findings support this conclusion. First, TF footprint analysis showed that EE increases AP-1 binding at regulatory regions in the DG, while IE reduces it in CA1 enhancers. Sparse Fos expression in DG granule cells may enhance the detection of EE-induced AP-1 activation, whereas weak basal Fos expression in CA1 pyramidal neurons facilitates detecting reduced AP-1 activity with IE. Second, over 300 genes associated with AP-1-regulated enhancers were identified, with their collective expression increased under EE and decreased under IE. These genes are enriched in synaptic functions, suggesting that AP-1 modulates their levels to support synaptic changes driven by rearing conditions. Third, both Fos and Fosb, key AP-1 components, were significantly regulated by environmental conditions in CA1 pyramidal neurons, in line with previous reports30,85. A DMR in the proximity of Fosb TSS showed reduced DNA methylation in EE-raised mice, suggesting a potential chromatin mechanism contributing to Fosb upregulation, consistent with evidence linking DNA demethylation to the expression of activity-regulated genes86. Our findings thereby position AP-1 as a driver of hippocampal circuit adaptation to EE and IE, impacting memory performance. Different subunits can be part of the AP-1 dimeric complex (JUN, JUNB, JUND, FOS, FOSB, FOSL1, FOSL2)87, and this functional redundancy has complicated loss-of-function studies88,89, as targeting individual components does not fully disrupt AP-1 activity. Only the simultaneous deletion of three AP-1 subunits in CA1 neurons has been shown to impair spatial memory in the MWM, in standard conditions45. Remarkably, despite this redundancy, deleting Fos in excitatory neurons partially impaired memory performance under EE, underscoring AP-1 role in orchestrating activity-dependent gene expression45,79,90 that supports cognitive enhancement. Future studies should also explore the impact of Fosb ablation on EE-induced effects since this subunit emerged in our screen as the most sensitive AP-1 component responding to EE. This finding is consistent with earlier observations on this TF. For instance, ΔFOSB, a truncated product of the Fosb gene, is induced in the hippocampus by environmental novelty and long-term exercise, modulates spine density in the CA1, and is required for hippocampal-dependent learning and memory91,92. Unlike other proteins in the FOS family that are rapidly but transiently induced in response to various stimuli, ΔFOSB gradually accumulates during stimulation and remains in the brain for weeks due to its exceptional stability93,94. This property may allow ΔFOSB to drive transcriptional changes that persist well beyond the removal of the initial stimulus, making it an ideal candidate to mediate the long-term consequences of rearing conditions on cognition.

Altogether, our multiomic approach revealed that rearing conditions modify the expression levels, DNA-binding activity and downstream transcriptional effects of AP-1. By demonstrating the lasting benefits of EE on memory, our findings support the translational potential of interventions combining physical exercise, cognitive stimulation, and social interaction as non-pharmacological therapies to counter cognitive impairment or decline20,22. Developing compounds that enhance AP-1 activity, thereby enabling coordinated modulation of downstream target genes, might also offers therapeutic potential to boost EE-based interventions aimed at mitigating cognitive decline.

Methods

Mouse strains and treatments

Mice were kept in a controlled environment with a constant temperature (23 °C) and humidity (40–60%), on 12 h light/dark cycles, with food and water ad libitum. They were maintained in a sterile room located within the Animal House at the Instituto de Neurociencias (CSIC-UMH). All animal experiments were performed in agreement with Spanish and European regulations and received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Dirección General de Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca from Generalitat Valenciana, protocols 2017/VSC/PEA/00233, 2021/VSC/PEA/0206, 2022/VSC/PEA/0235, and 2023/VSC/PEA/0177). All experiments were performed on female mice due to frequent fights between males in EE conditions and the difficulty of regrouping male mice after EE or IE. For EE, large cohorts of 10–15 3-week-old C57BL6/J female mice were housed together for 3 months in an ample cage (60 × 140 × 22 cm) with nesting material, wheels, tunnels and various toys of different shape and texture, which were changed every two weeks. For IE, 3-week-old C57BL6/J female mice were housed individually for 3 months in a small cage (10 × 20 × 12 cm) without nesting material and placed inside a special armchair, shielding them from social, acoustic and visual stimuli. Female mice kept in SC were raised in group of 4-5 mice per cage, with nesting material. The pCamKIIα-CreERT2 mouse strain95 (from EMMA, EM:02125) was crossed with the pCAG-[STOP]-Sun1-GFP mouse line96,97 (stock #021039 from Jackson Laboratory) to label the nuclei of forebrain principal neurons with the nuclear envelope protein SUN1 fused with the reporter GFP, in a tamoxifen-dependent manner (pCamKIIα-CreERT2 x pCAG-[STOP]-Sun1-GFP). To remove the STOP cassette and enable Sun1-GFP expression, pCamKIIα-CreERT2 x pCAG-[STOP]-Sun1-GFP mice received 5 intragastrical administrations of tamoxifen (Sigma Aldrich, 20 mg/mL dissolved in corn oil) orally every other day. To delete Fos gene in forebrain excitatory neurons, a mouse carrying floxed Fos alleles (f/f-Fos; strain B6;129-Fostm1Mxu/Mmjax from Jackson Laboratory)98 was crossed with the pCamKIIα-CreERT2 line to obtain mice homozygotes for the floxed Fos allele and carrying one copy of the inducible CreERT2 transgene. 3-week-old female mice were transferred to EE cages for 3 months and received 5 intragastrical administrations of tamoxifen every other day starting from P21. The following primers were used for genotyping: pCamKIIα-CreERT2 (GGTTCTCCGTTTGCACTCAGGA, CTGCATGCACGGGACAGCTCT, GCTTGCAGGTACAGGAGGTAGT), pCAG-[STOP]-Sun1-GFP (GCACTTGCTCTCCCAAAGTC, CATAGTCTAACTCGCGACACTG, GTTATGTAACGCGGAACTCC), Fosf/f (GAAGGGACGCTACTGACTGC, TAGCAGGGGAACAAAGAAGC). For KA experiments, mice were administered with 25 mg/Kg KA (or an equal volume of saline for controls) through intraperitoneal injection 1 h before being euthanized.

Behavioral tests

All behavioral tests were performed during the light cycle. The mice were allowed to habituate to the behavioral room for at least 45 min before each test. Behavioral equipment was cleaned with 70% ethanol after each test session to avoid olfactory cues. Mice behavior was monitored by the video tracking system SMART (Panlab S.L. Barcelona, Spain). To minimize potential effects of prior test history on behavioral responses, the tasks were performed in an order generally considered to progress form least to most invasive (Open Field, Y-maze, Novel Object Recognition, Radial Maze, Contextual Fear Conditioning, Morris Water Maze), with at least one week interval between each test. One cohort of EE/SC/IE mice was used for Open Field, Y-maze, Novel Object Recognition and Contextual Fear Conditioning. A second cohort of EE/SC/IE mice was used for Novel Object Recognition and Contextual Fear Conditioning. Two cohorts of EE-SC/SC-SC mice were used for Radial maze, Contextual Fear Conditioning and Morris Water Maze. Two additional cohorts of IE-SC/SC-SC mice were used for Radial maze, Contextual Fear Conditioning and Morris Water Maze.

The OF test was conducted in a 40 × 40 × 50 cm arena of white acrylic glass. Mice were placed individually in the centre of the arena and allowed to freely explore it for 10 min. The distance run in the centre and the periphery of the arena, the total distance traveled, and the average speed were analyzed using the Mouse Behavioral Analysis Toolbox (MouBeAT)99 for ImageJ.

The Y-maze was performed in a Y-shaped maze of white transparent Plexiglas. Mice were placed individually in the centre of the maze and allowed to freely explore the arms for 6 min. An entry in an arm occurs when all four limbs of the mouse are within an arm. The sequence of entries in the arms was manually scored. An alternation is defined as three consecutive entries into the three different arms. The alternation percentage was calculated with the following formula: n. of alternations * 100/ n. of entries −2.

For CFC protocol, mice were placed in a fear conditioning chamber (Panlab S.L., Barcelona, Spain) equipped with an electrified grid. In the conditioning session, mice were allowed to explore the fear conditioning chamber for 2 min before receiving a single 0.4 mA, 2 s footshock, and then remained in the chamber for 1 additional minute. The time animals remained still (freezing) before and after the footshock was registered through a piezoelectric sensor located at the bottom of the fear box, using the Freezing software (Panlab S.L.; Supp. Fig. S1G) or, in more recent experiments, with Pacwin v. 2.0.07 (Panlab Harvard Apparatus; Fig. 1D). 24 h later, for the recall session, mice were returned to the same chamber for 3 min, and their freezing behavior was measured.

For novel object recognition (NOR), habituation and testing took place in 40 × 40 × 50 cm white acrylic glass boxes. In a pilot experiment, mice were exposed for 5 min to different couples of plastic objects to select two that fulfilled the following conditions: mice had to show interest for both objects, with no overt intrinsic preference for one object compared to the other. In the two first days of the test, mice were habituated to the test cage for 5 min. On the training session (day 3), the animals were exposed for 5 min to two identical objects (familiar objects) placed on the opposite sides of the box. 24 h later, for the test session (day 4), the mice were exposed for 5 min to the familiar object and to a novel object. Object exploration was defined as approaching and sniffing the object or touching it with the forepaws. The time spent by the animals in investigating each object was manually scored from video recordings by an observer blind to the animal genotype. Mice with a total exploration time inferior to 5 s during the training or the test were excluded from the relative exploration time and discrimination index analyses. The discrimination index was calculated with the formula (TNOVEL − TFAMILIAR) / (TNOVEL + TFAMILIAR), where TNOVEL = time exploring the novel object, TFAMILIAR = time exploring the familiar object. Eight-arm radial maze test was performed as previously described100. Briefly, the test was conducted using an apparatus with eight equally spaced arms, each containing a food well at the end. The maze was placed in a soundproof room with external visual cues. Before testing, mice were food-deprived to 80–85% of their initial body weight to enhance motivation for food rewards. During pretraining, mice explored the maze freely and learned to retrieve single pellets from each arm. In the acquisition phase, all arms were baited, and mice had 25 min to collect all eight pellets. Trials ended when all pellets were consumed or time expired. The number of errors, i.e., the number of times a mouse re-enters an arm it has already visited and collected the reward from, was recorded.

Morris water maze test (MWM) was performed within a circular tank with a diameter of 170 cm, which was filled with non-toxic white paint. During the initial three days of the test, referred to as visible phase (V1—V3), a 10 cm diameter platform with a black flag was provided, and mice were trained to locate it in order to exit the water. From days four to seven, known as the hidden phase (H1–H4), the platform was submerged beneath the water surface in the centre of the target quadrant, and external cues were placed on the walls of the room. Subsequently, during days eight to twelve, referred to as the transfer phase (T1–T5), the platform was relocated to a new position, requiring the animals to learn its new location to be able to exit from the water. Each day, every mouse underwent four trials, with inter-trial intervals lasting from 30 to 60 min. The trials continued until the mouse reached the platform or for a maximum of 2 min. If the mice did not find the platform after 2 min, they were gently guided to it. Mice were returned to their cages only after staying on the platform for at least 10 s. 1-min memory retention probe trials (PT), conducted without the platform, were used to assess memory performance at the end of the hidden (PT2) and transfer phases (PT3).

Forelimb grip strength was assessed using a Grip Strength Meter (Ugo Basile, 47105/47106). Mice were allowed to grasp a horizontal metal bar with their forepaws and were gently pulled backward by the tail until they released the grid. The peak force (in grams) exerted before release was recorded. Each animal was tested in four consecutive trials, and the average of the two highest values was used for analysis.

CA1 and DG microdissection and Fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS)

Mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation and the CA1 and DG hippocampal layers were microdissected as previously described101. Briefly, brains were removed from the skull and bisected along the longitudinal fissure of the cerebrum. Then, the olfactory bulbs and cerebellum were removed. Positioning the cerebral hemisphere upwards allowed for the removal of the diencephalon (thalamus and hypothalamus) under a dissection microscope, thereby exposing the medial side of the hippocampus. Hippocampus boundaries were separated from the entorhinal cortex and, subsequently, CA3, CA1 and DG were brought into view. CA3 was initially removed, leaving the remaining DG and CA1 regions to be carefully separated along the septo-temporal axis of the hippocampus. All steps were performed at 4 °C unless indicated otherwise. The accuracy of the dissection was evaluated by RT-qPCR of CA1- and DG-specific markers. Tissues microdissected from 2 to 3 animals were pooled into a single sample. After tissue dissociation, nuclei were extracted by mechanical homogenization using a 2 ml Dounce homogenizer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 500 μl of Nuclei Extraction Buffer (NEB; Sucrose 250 mM, KCl 25 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, HEPES-KOH pH 7.8 20 mM, IGEPAL CA-630 0.5%, spermine 0.2 mM, spermidine 0.5 mM, and 1X proteinase inhibitors (cOmplete EDTA-free, Roche)). Tissues from 3 mice were pooled in each sample, having a total volume of 1.5 ml NEB containing the nuclei for each hippocampal layer. Samples were filtered in a 35 μm mesh capped tube and incubated with 0.01 mM DAPI for 10 min in darkness in a rotator. Nuclei isolation was accomplished by the preparation of a gradient of different densities in which nuclei stay in the interphase. Nuclei were diluted in Optiprep density gradient medium (1114542, Proteogenix) to a final concentration of 22% Optiprep. For the density gradient, 44% Optiprep was added to a centrifuge tube followed by 22% Optiprep containing the nuclei. Additional 22% Optiprep was added until the tube was filled. After centrifugation at 4000 g for 23 min, the phase containing the nuclei was collected in a new tube containing Nuclei Incubation Buffer (NIB: sucrose 340 mM, KCl 25 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, HEPES-KOH pH 7.8 20 mM, spermine 0.2 mM, spermidine 0.5 mM, 1X proteinase inhibitors, newborn calf serum 5%). Sorting of SUN1-GFP+ nuclei was performed in a flow-cytometer FACS Aria III (BD Bioscience) in collaboration with the Omics facility at the Instituto de Neurociencias. Sorted nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation (1000 g, 7 min, 4 °C) and destined to nuRNA-seq, ATAC-seq, H3K27ac CUT&TAG or DNA methylation assays. For each CA1 and DG sample, 75,000 SUN1-GFP+ nuclei were used for ATAC-seq, and underwent tagmentation and DNA purification before storage at −20 °C, whereas the remaining nuclei (approx. 700,000–1,000,000) were mixed with TRI-reagent (Merck) and stored at −80 °C for nuRNA-seq. Different groups of mice were used to obtain SUN1-GFP+ nuclei for H3K27ac CUT&TAG (150,000 and 200,000 nuclei per CA1 and DG sample, respectively) and WGBS (500,000 and 900,000 nuclei per CA1 and DG sample, respectively).

RNA extraction, retrotranscription and RT-qPCR

Mice were euthanized via cervical dislocation, and the CA1 and DG hippocampal layers or the whole hippocampus were dissected from the brain. All steps were performed at 4 °C unless indicated otherwise. RNA extraction was performed using TRI-reagent (Merck) as recommended by the manufacturer. After treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen) for 30 min at 25 °C to eliminate genomic DNA, RNA was precipitated with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol. RNA concentration was measured using NanoDropOne (Themo Scientific). RNA was retrotranscribed to cDNA using the RevertAid First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific) and analyzed by RT-qPCR with PyroTaq EvaGreen (Cultek) in a QuantStudio 3 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The following primers were used: Dsp (F: GCTGAAGAACACTCTAGCCCA, R: ACTGCTGTTTCCTCTGAGACA), Tdo2 (F: TTTATGGGCACTCTGCTT, R: GGCTCTGTTTACACCAGTTTGAG), Ccn3 (F: GTCACCAACAGGAATCGCCAGT, R: TACCTTGTCTGTTACTTCCTC), Fos (F: GCTTCCCAGAGGAGATGTCTGT, R: GCAGACCTCCAGTCAAATCCA). Gapdh was used as a reference gene (F: CATGGACTGTGGTCATGAGCC, R: CTTCACCACCATGGAGAAGGC).

nuRNA-seq

RNA was extracted from SUN1-GFP+ nuclei with TRI-reagent (Merck) as described for the RT-qPCR. rRNA depletion libraries were prepared (TruSeq Stranded Total RNA, Illumina), and single-end 50 bp sequencing was conducted in a HiSeq 2500 apparatus (Illumina). Fastq files quality was analyzed by FastQC (v0.11.9)102 and adapters were trimmed using TrimGalore (v0.39)103. The reads obtained were aligned to the GRCm38.100 mouse genome (mm10) using STAR (v2.7.9a)104. Mitochondrial reads and reads with mapq <30 were eliminated using Samtools (v1.13)105. The total number of reads sequenced and the percentage of aligned reads for each sample are illustrated in Supp. Data 11. The data analysis was conducted with custom R scripts (v4.1.0, 2021), Rsubreads (v2.6.4)106 and Mus_musculus.GRCm38.100.gtf annotation data. For differential expression analysis of the rearing effects in each neuronal type, likelihood rate test (LRT) was performed using DESeq2 (v1.32.0)107 including all the rearing conditions, which were normalized within the same DESeq2 object. Since our ‘full’ model only has one factor (rearing condition), the ‘reduced’ model was just the intercept (~1). Significant differences were considered if p adj <0.1. For heatmaps, the log2FC for each replicate was calculated over the mean of the normalized counts of the SC replicates. To generate BigWigs, Deeptools (v3.5.1)108 was used. For CA1 vs DG comparison, only the SC groups from both neuronal types were used. GO analysis was performed with gProfiler109 (Fisher’s one-tailed test with g: SCS (Set Counts and Sizes) correction for multiple comparisons, padj <0.05) and SynGO110 (Fisher’s one-tailed test with False Discovery Rate correction for multiple comparisons, q-value < 0.01). For Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)111, the complete gene list detected by nuRNA-seq in CA1 or DG was ranked by log2FC * -log10p-value. As a gene set, the 200 genes most strongly up-regulated in the hippocampus after kainate treatment were used29. Protein network analysis was performed with STRING53 taking into account textmining, experiments and databases as interaction sources. gProfiler, SynGO and STRING analysis were performed after conversion of the mouse genes to their human homologs using SynGO ID conversion tool.

For the evaluation of GFP expression in KA-treated mice, all the nuRNAseq dataset from29 were used to obtain the sfGFP sequence using velvet (v1.2.10)112 and it was introduced as an additional chromosome into the mouse reference genome mm10. nuRNA-seq reads in vehicle and after 1 h of KA injection were aligned to this new reference genome using STAR (v2.6.1a). Reads were then filtered for mapq >30 using Samtools (v1.9), then counts were calculated with Rsubread (v2.4.3) for the reference Mus Musculus.GRCm38.99.gtf where the sfGFP was included. The differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (v1.30.1).

ATAC-seq