Introduction

Predicting the reactants of organic reactions and planning retrosynthetic routes are fundamental problems in chemistry. On the basis of well-established knowledge from organic chemistry, experienced chemists can design routes for synthesizing target molecules possessing desired properties. However, retrosynthesis planning is still a challenging problem because of the huge chemical space1,2 of possible reactants and insufficient understanding of chemical reaction mechanisms. In recent decades, computer-aided synthesis-planning methods have developed in tandem with artificial intelligence (AI) and have assisted chemists in programming synthetic routes3,4,5,6.

Currently, retrosynthesis models are divided into template-based methods, semi-template-based methods, and template-free methods. Early retrosynthesis research focused on template-based models, which rely on reaction templates that describe reaction rules based on core units of chemical reactions. Models identify appropriate product-based reaction centers and match them with existing templates, ultimately retracing reactants and reagents. For instance, Segler et al.7 focused on correlations among molecular functional groups and built the first template-based deep learning model. GLN8 combined reaction templates and graph embeddings, resulting in high prediction accuracy. Recently, RetroComposer9 has been proposed to compose templates from basic building blocks extracted from training templates rather than only directly selecting from training templates, which achieved the state-of-the-art (SOTA) in the template-based models. Despite their abilities to interpret predicted reactions, template-based methods are restricted to the templates upon which they rely on10. Because the template library covers limited reactions, resulting in poor generalization and poor scalability11.

To avoid the limitations of the template library, semi-template-based methods, which predict reactants through intermediates or synthons, have been proposed. Specifically, reaction centers are first identified using a graph neural network to yield synthons, from which reactants are subsequently generated through semi-template-based models. Template redundancy can be minimized by retaining only the essential chemical knowledge, as many semi-templates are reduplicative. Gao et al.12 developed SemiRetro, the first semi-template framework boosting deep retrosynthesis prediction model. Zhong et al.13 introduced Graph2Edits, an end-to-end model that integrates two-stage procedures of semi-template-based methods into a unified learning framework. Notably, Graph2Edits not only enhances the applicability for handling some complex reactions but also improving the interpretability of the model’s predictions. Although semi-template-based methods have shown promise in accurately predicting retrosynthesis tasks, their handling of multicenter reactions is difficult.

In contrast to template- and semi-template-based methods, template-free methods directly generate potential reactants according to input products. Meanwhile, no expert knowledge is required at the inference stage. Liu et al.14 proposed the first template-free method, seq2seq, possessing an encoder-decoder architecture, including long short-term memory cells15, which treated retrosynthesis as a machine translation task by representing molecules as simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings16. Afterwards, Zheng et al.17 proposed SCROP to solve invalid output SMILES strings by integrating a grammar corrector into Transformer. However, several studies suggest that SMILES representation overlooks structural information in molecules and reactions. Compared with linear representations, graphic representations possess better interpretability. Therefore, Graph2SMILES18 integrates a sequential graphic encoder with a Transformer decoder to convert molecular graphs into SMILES sequences. To address the challenge for explaining deep learning methods, Wang et al.19 established RetroExplainer, enabling the quantitative interpretation of retrosynthesis planning by formulating retrosynthesis tasks as molecular assembly processes. Yao et al.10 focused on vital 2D molecular information and proposed NAG2G, which combined molecular graphics and 3D conformations to retain molecular details and incorporated atomic mapping between products and reactants through node alignment. In recent years, with the emergence of attention mechanisms20 and the advancement of natural language processing (NLP) models, template-free methods have attracted increasing attention.

In previous studies, researchers have faced limitations because of the constraints of the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) datasets21. The researchers have employed various strategies, including considering energy and chemical bond changes in chemical reactions within the model. However, the Top-1 accuracies of these models remained limited to approximately 55% probably because of insufficient available training data. Even the largest available database, USPTO-FULL, only contains about two million datapoints. In this study, we aim to leverage large language models (LLMs)22 trained on large-scale data to overcome the challenges posed by data bottlenecks. Using this approach, the model is expected to autonomously acquires chemical knowledge from large-scale data. In deep learning, researchers have recently explored using generated synthetic data23,24,25 to solve the problem of data scarcity. Although the quality of synthetic data may be slightly inferior to that of real-world data, it remains a feasible alternative for pre-training LLMs. Inspired by this, we developed a model for retrosynthesis planning, which facilitates the direct acquisition of chemical knowledge from extensive synthetic data, without the need for expert knowledge input, by treating SMILES notation as a linguistic representation. Notably, beyond the impact of data, reinforcement learning (RL)26,27 has been instrumental in advancing the performance of LLMs, serving as a pivotal factor in their success. To align LLMs to human preferences, RL from human feedback (RLHF)28,29,30 has been proposed and applied to numerous widely used LLMs, such as ChatGPT31, LaMDA32, and LLaMA233. Nevertheless, RLHF is resource-intensive and depends heavily on high-quality human preference labels. In response, Bai et al.34,35,36 introduced reinforcement learning from AI feedback (RLAIF), a novel approach that utilizes AI-generated feedback as a substitute for human labels. By leveraging AI-driven evaluations, RLAIF presents a promising and efficient alternative for training synthesis-planning LLMs37.

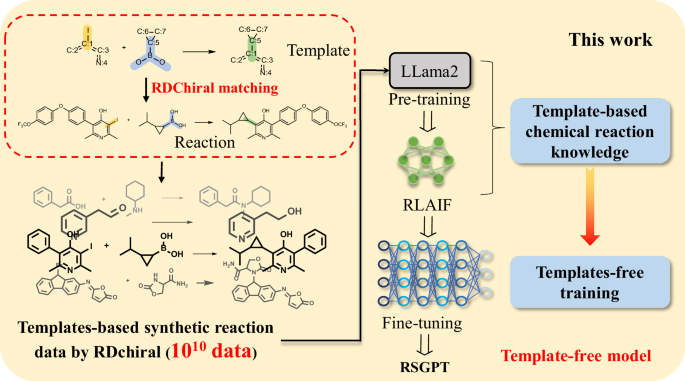

Herein, we proposed Retro Synthesis Generative Pre-Trained Transformer (RSGPT), a retrosynthesis planning model, leveraging the architecture of LLaMA2. Inspired by LLM training, the RSGPT training strategy was divided into pre-training, RLAIF, and fine-tuning stages. The RDChiral reverse synthesis template extraction algorithm38 was firstly used to generate chemical reaction data. This approach facilitates the precise alignment of the reaction center of an existing template with that of a synthon in a fragment library, subsequently enabling the generation of the complete reaction product—resulting in over 10 billion reaction data entries. Subsequently, the model was pre-trained using large-scale synthetic data to enhance the acquisition of chemical reaction knowledge through RSGPT. During RLAIF, RSGPT-generated reactants and templates based on given products. Then, RDChiral was employed to validate the rationality of the generated reactants and templates, with feedback provided to the model through a reward mechanism, enabling the model to elucidate the relationship among products, reactants, and templates. Finally, RSGPT was fine-tuned using specifically designated datasets to optimize its performance for predicting particular reaction categories (Fig. 1).

In this work, we generated 10 billion reactions using RDChiral38, followed by pre-training based on Llama233 architecture to enhance the acquisition of chemical reaction knowledge and used reinforcement learning from artificial intelligence feedback (RLAIF) to elucidate the relationships among products, reactants, and templates, rendering RSGPT as a template-free model.

We evaluated our method for generating synthetic data, and the tree maps (TMAPs)39 reveal that the generated reaction data not only encompass the existing chemical space of USPTO datasets but also venture into previously unexplored regions. This exploration substantially enhances retrosynthesis prediction accuracy. RSGPT, which was fine-tuned using USPTO-50k, USPTO-MIT, and USPTO-FULL datasets, predicts reactions more accurately than baseline models. In particular, RSGPT achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 63.4% for the USPTO-50k dataset, substantially outperforming previous models, which is considered the result of training based on a large volume of chemical reaction data. To further understand the contribution of each component in our training strategy, we conducted ablation studies by systematically removing specific parts of the training strategies to assess their impacts on the performance of our model. Additionally, RSGPT demonstrates strong performance in predicting single-step reactions, and when integrated with planning, it holds significant potential for identifying multi-step synthetic planning. Most importantly, RSGPT offers innovative insights and has the potential to scale across diverse chemical spaces in various scenarios.

Results

Synthetic data generated using RDChiral

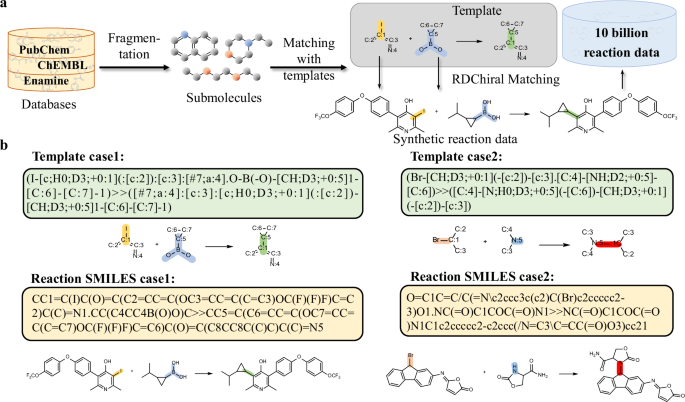

Inspired by the use of large-scale data for pre-training LLMs, we applied this strategy to RSGPT development. To meet the pre-training requirements of RSGPT, an open-source template database extracted using RDChiral was employed to generate synthetic data (Fig. 2a). BRICS method was used to cut the 78 million original molecules from PubChem40, ChEMBL41, and Enamine42 databases into fragments and obtain 2 million submolecules. Subsequently, the templates extracted from the USPTO-FULL dataset using the RDChiral reverse synthesis template extraction algorithm were collected. Then, submolecules were matched with templates’ reaction centers, and products were generated based on the corresponding templates. This method precisely aligned the reaction centers with those of synthons. Using this process, we obtained a total of 10,929,182,923 synthetic data entries. We aim to ensure the reasonableness of the generated data as much as possible through the templates extracted using RDChiral. To clearly visualize the generated reaction data, Fig. 2b shows a coupling and a nucleophilic substitution reaction. The resulting reactions both exhibit high degree of rationality. More examples of templates and corresponding generated reactions are available in Table S1.

a Method for generating synthetic data using RDChiral. Molecules from PubChem40, ChEMBL41, and Enamine42 were fragmented to submolecules. Submolecules were then matched with reaction centers of templates, as shown in the grey shaded part, and complete reactions were generated based on corresponding templates by concatenating reactants SMILES and products SMILES into a complete reaction text. b Examples of synthetic data. Case 1 is a coupling reaction, and Case 2 is a nucleophilic substitution reaction. The templates, reaction SMILES, and visualized reaction schemes for both examples are displayed.

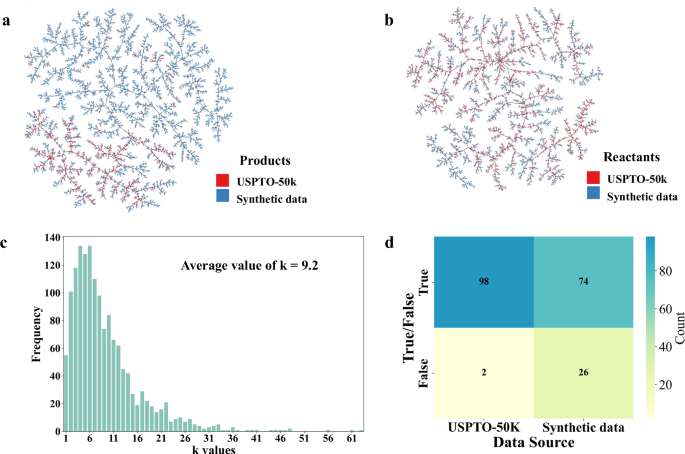

Since the template for the synthetic data is entirely derived from the USPTO dataset, it means that the synthetic data cannot include reaction types outside of those present in the USPTO dataset. However, it is inferred that the chemical spaces covered by the synthetic data and the USPTO-50k dataset are not identical. As shown in Fig. 3a, b, the chemical space distribution between the synthetic and real-world data was evaluated. To visualize the diversity, we generated TMAPs according to structural similarity, illustrating the diversity and distribution of reactions in the chemical space39. Products and reactants derived from the synthetic and USPTO-50k data were respectively sampled in the TMAPs. The products generated using RDChiral were more broadly distributed than those derived from the USPTO-50k dataset in the TMAP, while the distribution of the synthetic reactants closely resembled that of the synthetic reactants derived from the USPTO-50k dataset, indicating that the synthetic data exhibited a broader chemical space than the real-world data and allowing for the pre-training dataset to navigate reactions possessing different scaffolds or fragments. However, accurately quantifying the chemical reactions from the two data sources is extremely challenging. Hence, we present several examples of reactions from both USPTO-50k and the synthetic data to provide a more intuitive comparison (as shown in Figs. S1 and S2 and Supplementary Data 1, “USPTO-50k Examples” and Supplementary Data 2, “Synthetic Data Examples”). The chemical reactions in the synthetic data are more likely to encompass molecules with larger molecular weights or greater complexity, such as bicyclic or cage compounds.

a Reaction products were randomly selected to generate the Tree map (TMAP). Blue and red dots represent products from synthetic data and USPTO-50k51,60, respectively. b Reactants were randomly selected to generate the Tree map (TMAP). Blue and red dots represent products from synthetic data and USPTO-50k, respectively. c Distribution of k based on 1500 randomly selected synthetic data. Here, k represents the number of templates that can match a given set of reactants R. d Blind evaluation of the validity of 100 USPTO-50k data entries and 100 synthetic data entries by experts.

Meanwhile, a few synthetic data are indeed irrational. For instance, the generated reaction may contain multiple reaction centers or large sterically hindered groups. To assess the quality of the synthetic data, more in-depth evaluations were conducted. For a given set of reactants, there is usually a unique main product. Nevertheless, for a given reactant set, there are possible k templates that could have a match in the library. This indicate that the fraction of reasonable reactions in the synthetic dataset may be closer to 1/k. We collected 1500 sets of reactants, and the distribution of k values of them are demonstrated in Fig. 3c. The values of k are predominantly distributed within the range of 1–20, and the average value of k is 9.2, indicate that about 1/9 reactions in the synthetic data is reasonable. However, this statistic is too strict, as a given set of reactants may indeed yield different products under varying reaction conditions. Therefore, three chemical experts were invited to judge the validity of synthetic data based on more reasonable standards. A total of 100 reactions from the USPTO-50k database and 100 reactions derived from synthetic data were combined and shuffled. Three experts conducted a blind evaluation of each reaction, categorizing reasonable reactions as “True” and unreasonable reactions as “False” (as shown in Supplementary Data 3, “Experts Blind Evaluation” and Supplementary Data 4, “Baseline Negative Dataset”). The final determination of a reaction’s validity was made based on majority judgement among the experts. The proportion of reasonable reactions in the USPTO-50k dataset is 98%, whereas the proportion of reasonable reactions in the synthetic data is 74% (Fig. 3d). However, this is still considered acceptable in terms of the quality of the pre-training data.

To investigate whether synthetic data could lead to data leakage, a comparative analysis was also performed by matching the reactants in the synthetic data with those in the benchmark dataset. In single-reactant reactions, no reactant sets in the synthetic data are found to be identical to those in the USPTO-50k dataset. Additionally, in multi-reactant reactions, no completely consistent reactions have been found, and only 2064 synthons were matched with those in the USPTO-50k dataset, effectively avoiding the risk of data leakage.

Notably, in addition to providing a publicly available template database, RDChiral can be used to extract reaction templates for specific reactions, rendering it as a generalizable method. The collection of demand reactions, subsequent extraction of corresponding templates, and generation of synthetic data comprise a strategy that could be widely applied for generating synthetic data in molecular transformation-related fields.

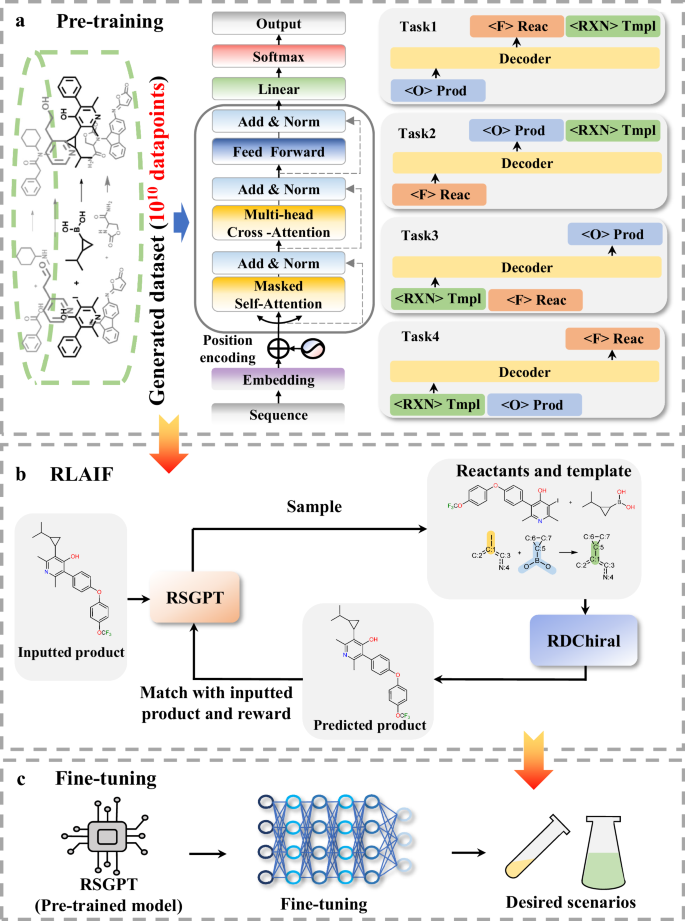

Workflow of RSGPT

For the training of our proposed model, RSGPT integrates pre-training, RLAIF, and fine-tuning training stages. LLaMA2 was employed to pre-train the model and learn chemical reaction information from large-scale synthetic data. Subsequently, RLAIF further aids the model in comprehending the relationship among reactants, products, and templates through feedback. Notably, templates were used at the pre-training and RLAIF stages to provide the model with a more comprehensive understanding of chemical reactions and are fundamental to the RLAIF. In the subsequent fine-tuning stage and inference module, we did not perform template matching on the products or provide any atomic mapping information. Finally, RSGPT could be fine-tuned using specific datasets to adapt to the corresponding chemical reaction space. The training process is shown in Fig. 4.

a Pre-training strategy of RSGPT. The RSGPT architecture is the transformer decoder, and four tasks were designed to capture the relationships among products, reactants, and templates. Task 1: The model is trained to predict reactants and templates based on the products; Task 2: The model is trained to predict products and templates and templates based on the reactants; Task 3: The model is trained to predict products based on templates and reactants; Task 4: The model is trained to predict reactants based on templates and products. b reinforcement learning from artificial intelligence feedback (RLAIF) strategy of RSGPT. RDChiral38 was employed to achieve feedback by validating whether the predicted reactants and templates could infer the given products. c RSGPT fine-tuning strategy. The model could be fine-tuned to adapt to specific reactions or substance transformations.

Pre-training: During pre-training, the predictions of the mutual conversion among the reactants, products, and templates were defined as four self-supervised learning tasks, enabling the model to thoroughly learn chemical reactions. Overall, these four tasks are defined as follows:

(1) The model is trained to generate reactants based on the given products and further outputs corresponding templates through autoregression;

(2) In contrast to task (1), the model is trained to predict products from reactants and subsequently generate templates;

(3) The model is trained to output products based on template and reactant conditions;

(4) The model is trained utilizing templates and products as inputs to predict reactants.

In this stage, the model is trained on a dataset of one billion chemical reactions to acquire chemical knowledge, which constitutes the core factor contributing to the strong performance in the subsequent evaluations.

RLAIF: Training language models using RL enables the optimization of complex sequence objectives, which has been proven to contribute to the success of modern LLMs. In this study, RDChiral was employed to automatically generate RL feedback by validating whether the predicted reactants and templates can infer given products. This approach was designed to enable the model to learn the relationships among products, reactants, and templates, thereby intelligently acquiring chemical knowledge. Through this method, the model was anticipated to infer products using a template-free method. Similar to task (1) during pre-training, the model was trained to sequentially generate reactants and templates from given products. Meanwhile, RDChiral was employed to backtrack products according to chemical reaction rules and RSGPT-generated reactants and templates. The backtracked and original input products were used for matching and scoring, with the results provided as the model’s feedback. If the match was successful, namely, the backtracked and original input products were identical, a score of 1 was assigned; otherwise, a score of 0 was assigned.

Fine-tuning: RSGPT was fine-tuned using different datasets to adapt to the corresponding chemical reaction space in different scenarios. At this stage, the model was only trained to output reactants on the basis of products in the training set. We selected USPTO-50k, USPTO-MIT, and USPTO-FULL, and benchmarked our model to baselines in the subsequent study.

Performance comparison on USPTO benchmark datasets

To assess the capabilities of our proposed RSGPT model for retrosynthesis planning, we applied the Top-k accuracy, which is the percentage of cases in the test set where the ground truth is included among the Top-k predicted candidates, as the main evaluation metric. To comprehensively evaluate the performance of RSGPT, we compared it against those of recent baseline approaches, including template-based, template-free, and semi-template-based methods.

As shown in Table 1, RSGPT demonstrates SOTA performance on the USPTO-50k dataset with reaction class unknown. Specifically, when the reaction class is unknown, our model achieves Top-1 and -10 accuracies of 63.4% and 93.0%, respectively, surpassing those of all the existing template-free methods. Furthermore, our model outperforms template- and semi-template-based methods, which are generally perceived to outperform template-free methods. For instance, RSGPT is more accurate than previous SOTA models R-SMILES43 and EditRetro by margins of 7.1% and 2.6% for Top-1 accuracies, respectively. To ensure a fair comparison with EditRetro, a similar 20-fold augmentation44,45 was applied to both the training and test sets. With 20-fold augmentation, RSGPT achieved a Top-1 accuracy of 77.0%, substantially outperforming EditRetro. In addition, when the reaction class was known, RSGPT’s Top-1 accuracy improved by 72.8% compared to those situations where the reaction class was unknown (Table 2). Proportion of ten types of reactions in the USPTO-50k dataset is shown in Fig. S3, and detailed Top-1 accuracies for different reaction classes derived from the USPTO-50k test set are presented in Fig. S4. The results indicate that RSGPT possesses high prediction accuracies for “acylation and related processes”, “reductions” and “protections” reactions, with Top-1 accuracies of 77.8%, 78.6%, and 77.9%, respectively. However, RSGPT’s accuracy in predicting “C–C bond formation” reactions are comparatively lower, with a Top-1 accuracy of merely 60.1%. Although “C–C bond formation” reactions account for 16.5% of all the reactions in the training set of USPTO-50k, which is a considerable proportion, this class of reactions frequently involves complex scaffold changes, which decrease the Top-1 accuracy. Meanwhile, on USPTO-50k test set, RSGPT demonstrates a high SMILES validity rate, with the Top-10 SMILES validity rate reaching 97.7% (Table S2). Furthermore, the average tanimoto similarity coefficient between its Top-1 output and the ground truth is as high as 0.840 (Table S3).

To demonstrate the generalization of RSGPT, we further evaluated its performance on the USPTO-MIT and USPTO-FULL datasets. As shown in Table 3, RSGPT also exhibited the best capabilities across all the metrics, including Top-1, -3, -5, and -10 accuracies for the USPTO-MIT dataset. RSGPT surpassed the runner-up model R-SMILES by margins of 3.6%, 7.9%, 5.5%, and 3.8% for Top-1, -3, -5, and -10 accuracies, respectively, and showed similar results for the USPTO-FULL dataset. Because the USPTO-FULL dataset is noisier than the clean USPTO-50k dataset, although RSGPT’s Top-1 accuracy decreased to 59.2%, RSGPT still outperformed the other baseline models.

During the evaluation, the model remarkably performed without relying on atomic mapping or any template information, suggesting that RSGPT’s behavior is attributed to the model learning characteristics from a wide range of chemical reactions during pre-training based on ten billion data.

Ablation study for interpretating

Here, the ablation study was conducted on USPTO-50k dataset to investigate the influences of each RSGPT training component, including pre-training, RLAIF, and data augmentation, on ablation (Table 4).

First, we comprehensively compared the impacts of pre-training and RLAIF on the Top-k accuracies (k = 1, 3, 5, and 10) of the RSGPT. Notably, during pre-training and RLAIF in ablation study, no data augmentation was employed, and in both the training and test sets, SMILES strings were represented using canonical SMILES. The results indicated that RSGPT’s prediction accuracy was optimized during both pre-training and RLAIF, achieving Top-1, -3, -5, and -10 accuracies of 63.4%, 84.2%, 89.2%, and 93.0%, respectively. RLAIF removal slightly decreased the accuracies by varying degrees ranging from 0.1% to 4.2%. Meanwhile, the gap between the Top-1 and -10 accuracies substantially increased to 33.0%, indicating that RLAIF-free training substantially decreased the reasonableness of the results behind the rank-1 output and RSGPT successfully learned the chemical knowledge from templates during RLAIF and was effectively applied to the template-free method. Furthermore, when the model was trained directly using the USPTO-50k training set while utilizing neither pre-training nor RLAIF, the accuracy substantially decreased, with the Top-1 accuracy dropping to only 26.4%. We inferred that the low accuracy was contributed to the removement of the atomic mapping information from original dataset. As shown in Fig. S5, when the model was trained using the USPTO-50k dataset that included atomic mapping, the Top-1 accuracy increased to 37.6%. While incorporating atomic mapping enhances accuracy, we recognize that this approach poses a risk of information leakage. These results suggest that pre-training is crucial for enhancing our model’s performance. Pre-training using a synthetic dataset containing 10 billion chemical reactions enables RSGPT to grasp the characteristics of chemical reactions and develop an understanding of the expansive chemical reaction space, which is the basis of its strong performance.

Next, we improved the RSGPT’s learning capacity and generalizability while minimizing the canonical SMILES dependence. Inspired by the work of Tetko et al.44 and Han et al.45, we augmented the SMILES data in the USPTO-50k dataset. During data augmentation, pre-training and RLAIF strategies were both employed. We implemented two distinct augmentation approaches. First, 20-fold augmentation was applied to the SMILES in the training set, covering both products and reactants. Alternatively, augmentation was implemented to the SMILES in both the training and test sets: 20-fold augmentation was applied to the SMILES in the training set, and five, ten, and 20-fold augmentations were applied to the SMILES in the test set. For nonaugmented data, a singular canonical SMILES representation was utilized for each item in the reactions. During the reasoning process with augmentation applied to the test set, Average Cumulative Log Probability based on Beam Search was utilized. (Fig. S6) Table 4 reveals that the accuracy decreased when augmentation was merely applied to the training set, with the Top-1 accuracy dropping to 55.1%, which is expected, as the training set comprises numerous noncanonical SMILES, there is a disparity in the canonical SMILES input during the model inference. When applying 20-fold augmentation to both product and reactant data, the prediction accuracy substantially improved, achieving Top-1, -3, -5, −10 accuracies of 77.0%, 90.9%, 94.3%, and 96.7%, respectively. Furthermore, accuracies exhibit clear saturation characteristics as the augmentation parameter n increases from 10 to 20. Consequently, although compared to recent baseline models, RSGPT have already achieved SOTA performance, the accuracy could be further enhanced by augmenting both products and reactants.

Analysis of single-step prediction cases

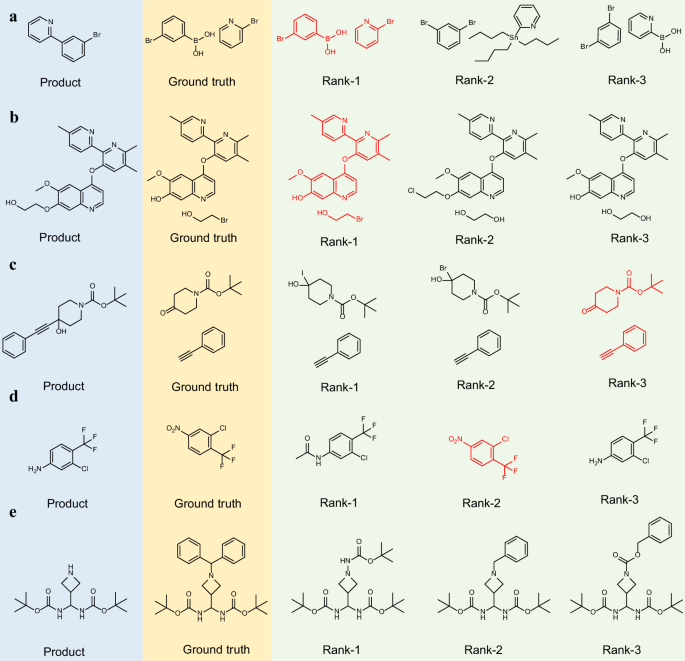

To intuitively understand retrosynthesis predictions, we visually analyzed two randomly selected molecules derived from the USPTO-50k test set and the Top-3 RSGPT predictions.

As shown in Fig. 5a, the first example showcases the synthesis of 2-(3-bromophenyl)pyridine. The reaction site is located at the chemical bond between two aromatic rings. The rank-1 prediction precisely matches the ground truth, identifying the reaction as a Suzuki coupling reaction46. Similarly, the rank-2 and -3 predictions describe Stille47 and Suzuki couplings involving the m-dibromobenzene reactant, respectively. The second example, depicted in Fig. 5b, concerns the synthesis of an ether. The rank-1 prediction correctly identifies this as Williamson ether synthesis, which is consistent with the ground truth. The rank-2 prediction is inaccurate, while the rank-3 prediction proposes ether bond formation via two hydroxyl groups, which is considered as a plausible reaction. Another nucleophilic substitution reaction is shown in Fig. 5c, RSGPT predicted three sets of reactants, all associated with substitution reactions. The ground truth corresponds to the rank-3 prediction. Figure 5d illustrates a nitro group reduction. The second model-predicted result aligns with the ground truth. Notably, in this example, the rank-3 predicted reactant is identical to the product, which is attributed to the chaotic outputs of the NLP model—a recognized limitation of our approach. The final example involves a deprotection reaction (Fig. 5e). Unlike the benzhydryl protecting group used in the ground truth, our model predicts more commonly used Boc, benzyl, and Cbz protecting groups. The Boc group does not address selectivity issues, whereas the benzyl and Cbz groups are considered as reasonable alternatives.

a Suzuki coupling; b Williamson ether synthesis; c Nucleophilic substitution; d Reduction; e Deprotection. The blue background in the diagram represents the product structure, while the yellow background corresponds to the reactant structure serving as the ground truth. The green background illustrates the top-three predicted results generated by RSGPT. Output structures consistent with the ground truth are marked in red.

Multi-step retrosynthesis planning using RSGPT

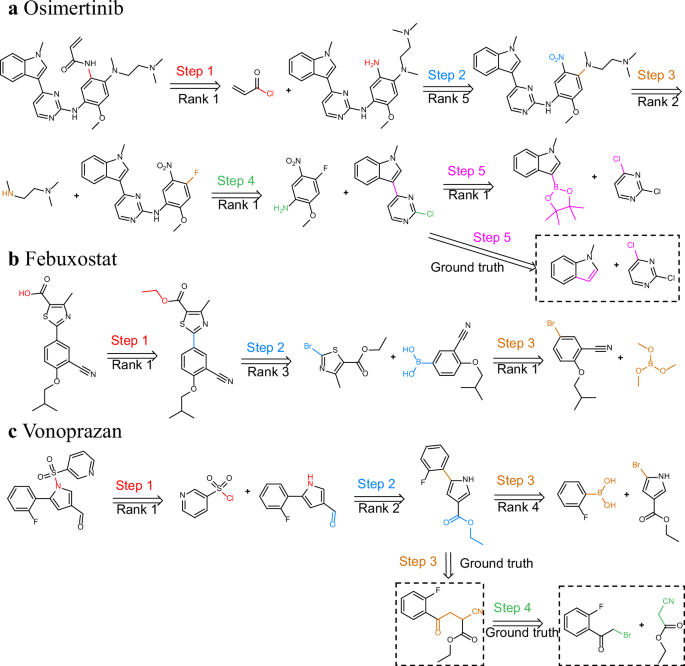

To validate RSGPT’s applicability in synthesis planning, we further expanded single-step predictions to multi-step retrosynthesis predictions. Notably, although RSGPT was originally designed for single-step reaction predictions rather than automated multi-step completions, it extends to multi-step reactions by sequentially predicting each single-step reaction.

The first example is Osimertinib48, an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor approved in 2014 for clinically treating non-small cell lung cancer. As shown in Fig. 6a, RSGPT successfully predicted a five-step synthesis, similar to the synthetic route detailed in the literature, tracing the synthetic route from commercially accessible reactants to the target molecule. The predicted reverse synthesis begins with an acylation reaction ranked as the top prediction, followed by nitro group reduction in the second step. Subsequently, a nucleophilic substitution with trimethylethane-1,2-diamine as the nucleophile was correctly identified, ranking second. In the fourth step, another nucleophilic substitution was accurately predicted as the top choice. For the final step, the highest-ranked prediction was Suzuki coupling rather than Friedel-Crafts arylation, which was also considered as a rational alternative.

a Third-generation EGFR inhibitor osimertinib. b Xanthine oxidase inhibitor Febuxostat. c Potassium-competitive acid blocker Vonoprazan. Reaction centers are distinguished by distinct colors, and atomic and bond transformations are illustrated at each reaction step.

The second example is Febuxostat49, a medication for treating gout that selectively inhibits xanthine oxidase (Fig. 6b). Our model identified carboxylic acid ester hydrolysis as the first step, ranking it as the top prediction. Afterwards, the key Suzuki coupling was accurately predicted. Finally, 3-cyano-4-isobutoxyphenyl boronic acid was obtained from the reaction between trimethyl borate and 5-bromo-2-isobutoxybenzonitrile.

The third example is Vonoprazan50, a potassium-competitive acid blocker for treating gastric and duodenal ulcers. The synthesis planning suggested by our model is shown in Fig. 6c. For the first step, RSGPT predicted a sulfonylation reaction, which is consistent with literature reports. The second step involves a reduction from an ester to an aldehyde. Unlike the ground truth, the model bypasses the synthesis of the pyrrole ring and instead predicts that ethyl 5-(2-fluorophenyl)-pyrrole-3-carboxylate is produced by coupling 2-fluorophenyl boronic acid and ethyl 5-bromo-pyrrole-3-carboxylate.

Discussion

In this study, we introduced RSGPT, a GPT model equipped with an LLama2 architecture, using a template-free method for retrosynthesis planning. Reactions were represented using SMILES strings treated as sequences in natural language. In contrast to previous template-free methods, RSGPT incorporated LLM strategies, encompassing pre-training, RLAIF, and fine-tuning. To meet the demand for substantial pre-training data, an ingenious approach was employed to generate 10 billion reactions by matching molecules with templates using RDChiral, allowing for the synthetic reaction data to adapt to chemical reaction principles, which is a crucial highlight of this study. Through the synthetic data generated using this method, RSGPT learned the characteristics of chemical reactions and the vast chemical reaction space containing diverse structures. Meanwhile, the introduction of RLAIF enabled the further elucidation of the relationship between reactions and templates, allowing for RSGPT to generate more potential reactant combinations.

Evaluations on the benchmark USPTO-50k dataset showed that RSGPT achieves promising performance with a 63.4% Top-1 accuracy. Furthermore, we evaluated our method on the USPTO-MIT and USPTO-FULL datasets, where it possessed Top-1 accuracies of 63.9% and 59.2%, respectively, demonstrating the marvelous performance and generalization of RSGPT for different datasets. Ablation studies revealed the contributions of various components, including training strategies and data augmentation, underlining the practical application potential of the RSGPT approach. A further case study revealed that RSGPT accurately predicted the multi-step retrosynthesis planning of clinical drugs, indicating its practical utility and highlighting its potential to advance development of retrosynthesis models.

Overall, this work presents the following contributions:

(1) We established a RSGPT model, which possesses an accuracy superior to those of baseline methods;

(2) RSGPT learned the rules of chemical reactions directly from large-scale reaction data without relying on any input from established chemical knowledge;

(3) We used templates to construct synthetic datasets, satisfying the high-volume data requirements of LLMs;

(4) We selected the open-source template library offered by RDChiral, as outlined in Coley’s research. Nevertheless, the templates are not restricted to specific libraries, and RDChiral could derive reaction templates from particular reactions, rendering it as a generalizable method. By gathering desired reactions, extracting templates, and generating synthetic data, the process allows for remarkable scalability in training models for large-scale chemical reactions;

(5) During synthetic data generation, our approach strictly follows chemical reaction template rules and constraints.

The RSGPT model can advance research in the total synthesis of natural products, elucidation of biosynthetic pathways, and design of metal chelates. Although these fields lack large-scale data, the RDChiral-based synthetic data generator offers a feasible alternative solution. This workflow provides application potential in multiple important chemistry-related fields.

Although RSGPT has shown promising performance, this study still has several limitations that hinder the further improvement of model’s efficiency. Primarily, a more advanced method is required for generating synthetic data. Despite the availability of numerous reaction items from existing methods, the data quality must still be improved. Meanwhile, the RDChiral method used for synthesizing reaction data is only applicable to chemical reactions involving 1 to 3 reactants. Second, RSGPT-generated reactants are not chemically explainable, obfuscating the prediction process. Finally, our RSGPT model has not yet accounted for reaction conditions and other factors such as solvent. By addressing these limitations, RSGPT could further advance researches of retrosynthesis models and enable its widespread application in various domains involving substances transformations. Meanwhile, the incorporation of a broader range of reaction data spanning a more-extensive chemical space would facilitate intelligent retrosynthetic prediction advancement.

Methods

Generation of synthetic data

An open-source template database extracted using RDChiral was employed to generate synthetic data. Reactions were extracted by mining text from United States patents published between 1976 and 2016. The reactions are available as SMILES, where data on 77,028,926, 834,004, and 731,408 original molecules were collected from the PubChem, ChEMBL, and Enamine databases, respectively. BRICS algorithm of RDKit (version 2022.9.5) was used to divide the original molecules into 2,022,796 unique fragments, and hydrogen atoms were added to the submolecules, which were then matched with template reaction centers, and products were generated based on the corresponding templates. Specifically, each submolecule in the library was employed to verify if it matched the template’s reaction center. The appropriate fragments, including the corresponding reaction center, were selected to form a complete reaction SMILES. Using this process, we obtained a total of 10,929,182,923 synthetic data entries. In addition, we thoroughly examined the synthetic reaction data to ensure that the generated data did not overlap with the USPTO-50k, USPTO-MIT, and USPTO-FULL test datasets.

Benchmark datasets and data preprocessing

To assess the performance of the RSGPT model, the USPTO-50k, USPTO-MIT, and USPTO-FULL benchmark datasets were chosen because they encompass a wide range of chemical reactions, allowing for a thorough evaluation of RSGPT’s capabilities in retrosynthesis prediction. The high-quality USPTO-50k dataset comprised approximately 50,000 reactions sourced from the US patent literature. To confirm the generalizability of RSGPT, we additionally included the USPTO-MIT and USPTO-FULL datasets, which encompass more chemical reactions. For a fair comparison, we used the same version and splits as those used in previous work. The USPTO-50k and USPTO-FULL datasets were provided by Yan et al.51 The USPTO-MIT dataset was provided by Chen et al.52 and Yan et al.51 The USPTO-50k, USPTO-MIT, and USPTO-FULL datasets were divided into 40/5/5 K, 400/40/30 K, and 800/100/100 K training/validation/test sets, respectively.

Additionally, to avoid data leakages due to the atomic mapping algorithm, we removed the atomic mapping and converted the strings to canonical SMILES, ensuring that the reaction centers’ positions were not concentrated at the first position of the atomic arrangement. Meanwhile, reactions containing no products or just single ions reactants were removed from the datasets. Additionally, reactants containing individual heavy atoms were excluded from the reaction.

When the reaction class included, two related tokens were added to the reaction equation. One is the prompt token <class>, representing the reaction class known; the other is a chemical reaction category label ranging from 1 to 10, which corresponds to ten different types of chemical reactions.

Distinct data augmentation approaches were used. First, 20-fold augmentation was applied to the SMILES in the training set, covering both products and reactants. Alternatively, 20-fold augmentation was implemented for SMILES in both the training and test sets, involving augmentation of both products and reactants in the training set while exclusively augmenting products within the test set. For 20-fold augmentation, the canonical SMILES was presented as multiple SMILES strings rooted at different atoms in each molecule using RDKit (Landrum, G. A.). Therefore, the SMILES in the training set are represented by one canonical SMILES reaction and nineteen noncanonical SMILES reactions. Similarly, the products in the test set are represented by one canonical SMILES and nineteen noncanonical SMILES.

Problem formulation

In this paper, our objective is to systematically investigate the pivoting of pre-trained models toward knowledge-intensive domains. The training comprised a knowledge injection phase using template-based synthetic data to enrich the language model and a subsequent adjustment phase using specific real inversely synthesized data to align the model with the distribution of real retrosynthesis scenarios.

Model architecture and configurations

Our model is built upon LLaMA2, a transformer architecture–based decoder-only LLM. Similar to other transformer-based LLMs, LLaMA2 comprises an embedding layer, multiple transformer blocks, and a language model head while incorporating prenormalization, SwiGLU activation, and rotary embeddings53. LLaMA2 was employed as the RSGPT model architecture with 3,227,570,176 parameters. For vocabulary tokenization, byte pair encoding (BPE)54, a subword segmentation algorithm that effectively addresses the issues of out-of-vocabulary words and the data sparsity in NLP, was used. In language modeling, BPE enhances the vocabulary by allowing for the representation of rare and compound words as sequences of more frequent subword units, not only improving the handling of rich morphological language structures but also contributing to more efficient neural network training by reducing the vocabulary’s complexity and size. Overall, BPE strikes a balance between character- and word-level tokenizations, enabling more efficient training for retrosynthesis predictions by avoiding unnecessary vocabulary tokens.

For the pre-training model, we employed a 24-layer LLaMA2 architecture comprising 2,048 hidden-layer dimensions and a backbone comprising 32 attention heads. To ensure robust convergence, we utilized the cosine annealing algorithm55 to dynamically adjust the optimization learning rate from 0 to 1 × 10−4. The parameters were optimized using AdamW56. During pre-training, the batch size hyperparameter was set at 4 (where 20 data samples were concatenated to 1 data). Training spanned 62 epochs across 8 A100 GPUs with DeepSpeed57. For fine-tuning, because of the consistent data structure, we directly applied the cosine annealing algorithm at a final learning rate of 1 × 10−5 over five epochs. RL employed settings identical to those of the fine-tuning phase.

At the training stage, assuming that the text input is a sequence of tokens, e.g., X = {x1, x2,…, xN}, where each xi is a text token, and N is the total sequence length, the training objective is to minimize the autoregressive loss, with the major difference being whether to compute the loss of the entire sequence or only a subsequence.

Pre-training module

For knowledge injection, the default autoregressive loss was simply minimized, and all the SMILES in the chemical knowledge could be used for the model to accumulate chemical knowledge SMILES strings, which are formulated as follows:

$${{{\rm{L}}}}\left(\Phi \right)=-\sum \log \Phi ({u}_{i}|{u}_{ < i}),$$

(1)

where \({u}_{ < i}\) indicates the tokens appearing before index i, and \(\varPhi\) represents the model’s parameters.

We pre-trained the RSGPT model using the standard causal language modeling (CLM) task53. When provided with an input token sequence, X = (x0, x1, x2,…, xn), the model was trained to autoregressively predict the subsequent token (xi). Mathematically, the objective was to minimize the negative log-likelihood given by

$${{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{CLM}}}}}(\Phi )={{{\rm{E}}}}_{x\sim {D}_{{{{\rm{PT}}}}}}\left[-{\sum}_{i}\log ({{{\rm{P}}}}({x}_{i}|{x}_{0},{x}_{1},...,{x}_{i-1};\Phi ))\right],$$

(2)

where \(\Phi\) represents the model’s parameters, DPT is the synthetic pre-training data, \({x}_{i}\) is the token to be predicted, and x0, x1, …, xi-1 represent the context.

Supervised fine-tuning module

Pre-trained language models often do not follow user commands and frequently generate unexpected content because the language modeling objective in Eq. (2) focuses on predicting the next token rather than “answering questions as instructed.” To align the behavior of the language model with our intent in reverse composition, fine-tuning can be employed to explicitly train the model to follow instructions.

At this stage, the token sequence is further split into instruction I (representing the given products or reactants) and response R (the model’s output) as follows:

$${{{\rm{L}}}}(\Phi )=-{\sum} _{{u}_{i}\in {{{\rm{R}}}}}\log \varPhi ({u}_{i}|{u}_{ < i},I),$$

(3)

For fine-tuning and inference, we adopted Stanford Alpaca templates, and the input sequence could be expressed as follows:

Below is an instruction for four task description:

Task1:

### Instruction:

<Isyn> <O>products

### Response:

<F>reactants <RXN>templates

Task2:

### Instruction:

<Syn> <F>reactants

### Response:

<O>products <RXN>templates

Task3:

### Instruction:

<Syn> <RXN>templates <F>reactants

### Response:

<O>products

Task4:

### Instruction:

<Syn> <RXN>templates <O>products

### Response:

<F>reactants

where <Isyn> and <Syn> are prompt tokens that remind the model that “this task is a retrosynthesis task” or “this task is a synthesis task”. <RXN>, <O>, and <F> are prompt tokens that represent the templates, products, and reactants, respectively. The templates, products, and reactants in the Stanford Alpaca templates are SMILES chunk tokens.

The loss is only calculated based on the “<O> or <F>” part of the input sequence and can be expressed as follows:

$${{{{\rm{L}}}}}_{{{{\rm{SFT}}}}}\left(\Phi \right)={{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{{\rm{x}}}}}\sim {D}_{{{{\rm{SFT}}}}}\left[-{\sum}_{{{i}}\in \left\{ < {{{\rm{O}}}} > {{{\rm{or}}}} < {{{\rm{F}}}} > \right\}}\log \left({{{\rm{P}}}}\left({x}_{i} | {x}_{0},{x}_{1},...,{x}_{i-1};\varPhi \right)\right)\right]$$

(4)

where \(\Phi\) represents the model’s parameters, DSFT is the synthetic data, \({x}_{i}\) is the token to be predicted for the products or reactants, and \({x}_{0}\), \({x}_{1}\), \(...\), \({x}_{i-1}\) represent the context.

RLAIF module

Our language model was further trained following the RL method. The aim of RLAIF, an emerging approach combining RL with feedback generated by AI systems to improve the performance and alignment of models with human preferences, is to enhance molecule generation efficiency by guiding the model to adhere to templates and leveraging the pretrained language model as an optimizing policy. In this framework, the model generates outputs, which are then evaluated based on an RDChiral algorithm. The received feedback is utilized to adjust the model’s parameters, enabling it to learn from both its successes and failures in a more guided manner. RLAIF aims to fine-tune the model’s behavior by actively incorporating feedback loops prioritizing chemical reaction rules. This method addresses the limitations of traditional supervised learning by enabling models to adapt dynamically to varying chemical reactions and preferences, ultimately enhancing their robustness and applicability in real-world scenarios.

At this stage, we optimized the following objective:

$$\frac{\arg \max }{{{\uppi }}}\,{{{{\rm{E}}}}}_{{{p}}\sim {{D}},{{g}} \sim {{\uppi }}}[{{{\rm{R}}}}(g|p)]$$

(5)

We iteratively improved the policy by sampling p prompts from our dataset D and g generations from the policy (π) by employing the proximal policy optimization (PPO) algorithm and loss function.

During optimization, the final reward function is expressed as follows:

$${{{\rm{R}}}}({{g}}|{{p}})={\widetilde{{{{\rm{R}}}}}}_{{{\rm{c}}}}({{g}}|{{p}}){-} {{{\upbeta }}{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{{{{\rm{KL}}}}}({\uppi }_{\uptheta }({{g}}|{{p}})||{{{\uppi }}}_{0}({{g}}|{{p}})),$$

(6)

By sampling p prompts from dataset D and generating g outputs sampled from policy πθ, we iteratively improved the policy by employing the PPO algorithm and a specific loss function. During optimization, the final reward function includes a penalty term, such as that in Eq. (6), for deviations from the original policy (π0). Consistent with observations from other studies, this constraint is very beneficial for training stability. Rc = Rs + Rh, representing the sum of the effectiveness (Rs) and adherence to the Rh template’s reward models, was defined, and the model evaluated whether the generated responses were chemically reasonable and complied with the chemical reaction template’s rules, respectively.

Augmentation of test set

During the reasoning process with augmentation applied to the test set, Average Cumulative Log Probability based on Beam Search was utilized. Specifically, when n-fold test augmentation was employed to compute Top-k accuracy, the computational procedure involves three stages: (1) Prediction Generation: For each test case, RSGPT produces n groups of predictions. (2) Beam Search Execution: For each prediction group, beam search is configured with a specified beam size to generate beam size-dependent candidates. These candidates are then individually sorted within their respective groups using the Average Cumulative Log Probability scores. (3) Top-k Aggregation: Sequentially collect Top-1, Top-2,…, predictions from all n groups until the accumulated candidates surpass the target k. These candidates are re-ranked globally, and the Top-k highest-scoring predictions are selected as the final outputs. The Top-k accuracy is subsequently calculated based on this refined set.

At each step of the expansion process, the model predicts the next possible token for the current sequence and provides the probability distribution for each token. In the beam search process, a set of multiple candidate sequences is generated, each with a corresponding cumulative log probability score. If the original sequence is S (reparents the context \({x}_{1}\), \({x}_{2}\), \(...\), \({x}_{t}\)) and its cumulative log probability score is \({{\rm{L}}}\left(S\right)\), then when attempting to extend it with a new token \({x}_{t}\), the score of the new sequence S’ is as follows:

$${{{\rm{L}}}}({{S}}^{\prime})={{{\rm{L}}}}({{S}})+\frac{1}{{{{\rm{T}}}}}\log ({{{\rm{P}}}}({{{x}}}_{{{t}}}|{{{x}}}_{1},{{{x}}}_{2},\ldots {{{x}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}})),$$

(7)

The sum of the logarithmic probabilities equals the logarithm of the cumulative probability of the entire sequence, as follows:

$$\log {{{\rm{P}}}}({{{x}}}_{1},{{{x}}}_{2},\ldots {{{x}}}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}})={\sum }_{{{i}}=1}^{t}\log {{{\rm{p}}}}({x}_{i}|{x}_{1},{x}_{2},\ldots {x}_{{{{\rm{t}}}}}),$$

(8)

The higher this probability, the greater the model’s confidence in the text. During outputting process, results with higher cumulative logarithmic probabilities are assigned higher ranks.

Tree maps

To visualize the chemical space of reactants and analyze the similarity between different SMILES strings, the TMAP (Tree map) algorithm (version 1.2.1), which leverages locality-sensitive hashing (LSH) forests and Minimum Hashing Fingerprint (MHFP) encodings were employed. The process began with the preparation of two sets of SMILES strings: one set representing reactants from the USPTO dataset, and the other set representing reactants from synthetic data. These sets were combined into a single list, and numeric labels were assigned to distinguish the two datasets. Each SMILES string was encoded into an MHFP fingerprint using the MHFP encoder with a permutation length of 512. The resulting fingerprints were stored as TMAP. An LSH forest was then initialized with the same permutation length to maintain consistency with the MHFP fingerprints. The coordinates for the TMAP layout were computed from the LSH forest, which produces a 2D embedding of the chemical space. In this embedding, molecules with similar fingerprints are positioned closer together, while dissimilar molecules are spaced farther apart, enabling a clear comparison of their respective chemical spaces.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. USPTO datasets, the weight files of RSGPT, the results of augmentation test and the data for synthetic data the generation in this study were uploaded to Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15304009)58. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code of this work and associated trained models are available at https://github.com/jogjogee/RSGPT59.

References

Tibo, A., He, J., Janet, J. P., Nittinger, E. & Engkvist, O. Exhaustive local chemical space exploration using a transformer model. Nat. Commun. 15, 7315 (2024).

Bagal, V., Aggarwal, R., Vinod, P. K. & Priyakumar, U. D. MolGPT: molecular generation using a transformer-decoder model. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 2064–2076 (2021).

Corey, E. J., Long, A. K. & Rubenstein, S. D. Computer-assisted analysis in organic synthesis. Science 228, 408–418 (1985).

Corey, E. J. & Wipke, W. T. Computer-assisted design of complex organic syntheses. Science 166, 178–192 (1969).

Han, Y. et al. Computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) and machine learning: optimizing chemical reaction conditions. Chemistry 30, e202401626 (2024).

Szymkuć, S. et al. Computer-assisted synthetic planning: the end of the beginning. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 5904–5937 (2016).

Segler, M. H. S., Preuss, M. & Waller, M. P. Planning chemical syntheses with deep neural networks and symbolic AI. Nature 555, 604–610 (2018).

Dai, H., Li, C., Coley, C., Dai, B. & Song, L. Retrosynthesis prediction with conditional graph logic network. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 32, 8870–8880 (2019).

Yan, C., Zhao, P., Lu, C., Yu, Y. & Huang, J. RetroComposer: composing templates for template-based retrosynthesis prediction. Biomolecules 12, 1325–1339 (2022).

Yao, L. et al. Node-aligned graph-to-graph: elevating template-free deep learning approaches in single-step retrosynthesis. JACS Au 4, 992–1003 (2024).

Dong, J., Zhao, M., Liu, Y., Su, Y. & Zeng, X. Deep learning in retrosynthesis planning: datasets, models and tools. Brief. Bioinform. 23, 1–15 (2022).

Gao, Z., Tan, C., Wu, L. & Li, S. Z. SemiRetro: semi-template framework boosts deep retrosynthesis prediction. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2202.08205 (2022).

Zhong, W., Yang, Z. & Chen, C. Y.-C. Retrosynthesis prediction using an end-to-end graph generative architecture for molecular graph editing. Nat. Commun. 14, 3009 (2023).

Liu, B. et al. Retrosynthetic reaction prediction using neural sequence-to-sequence models. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 1103–1113 (2017).

Hochreiter, S. Long Short-Term Memory (Neural Computation MIT-Press, 1997).

Weininger, D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. Introduction to methodology and encoding rules. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 28, 31–36 (1988).

Zheng, S., Rao, J., Zhang, Z., Xu, J. & Yang, Y. Predicting retrosynthetic reactions using self-corrected transformer neural networks. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 47–55 (2020).

Tu, Z. & Coley, C. W. Permutation invariant graph-to-sequence model for template-free retrosynthesis and reaction prediction. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 62, 3503–3513 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Retrosynthesis prediction with an interpretable deep-learning framework based on molecular assembly tasks. Nat. Commun. 14, 6155 (2023).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 30, 5998–6008 (2017).

Schneider, N., Lowe, D. M., Sayle, R. A., Tarselli, M. A. & Landrum, G. A. Big data from pharmaceutical patents: a computational analysis of medicinal chemists’ bread and butter. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4385–4402 (2016).

Thirunavukarasu, A. J. et al. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 29, 1930–1940 (2023).

Jordon, J. et al. Synthetic Data–what, why and how? Preprint at, https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.03257 (2022).

Tripathi, S. et al. In Learning to generate synthetic data via compositing, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 461–470 (2019).

Raghunathan, T. E. Synthetic data. Annu. Rev. Stat. Appl. 8, 129–140 (2021).

Li, Y. Deep reinforcement learning: an overview. Preprint at, https://arxiv.org/abs/1701.07274 (2017).

Kaelbling, L. P., Littman, M. L. & Moore, A. W. Reinforcement learning: a survey. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 4, 237–285 (1996).

Cui, G. et al. Ultrafeedback: Boosting language models with high-quality feedback. International Conference on Machine Learning (2023).

Wang, B. et al. Secrets of rlhf in large language models part ii: reward modeling. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.06080 (2024).

Zheng, R. et al. Secrets of rlhf in large language models part i: PPO. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.04964 (2023).

Radford, A. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training (2018).

Thoppilan, R. et al. Lamda: language models for dialog applications. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2201.08239 (2022).

Touvron, H. et al. Llama 2: open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.09288 (2023).

Li, A. et al. Hrlaif: improvements in helpfulness and harmlessness in open-domain reinforcement learning from AI feedback. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.08309 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. RLAIF vs. RLHF: Scaling reinforcement learning from human feedback with AI feedback. In Proc. 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2024).

Lee, H. et al. Rlaif: scaling reinforcement learning from human feedback with AI feedback. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.00267 (2023).

Sharma, A. et al. A critical evaluation of ai feedback for aligning large language models. Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst. 37, 29166–29190 (2024).

Coley, C. W., Green, W. H. & Jensen, K. F. RDChiral: an RDKit wrapper for handling stereochemistry in retrosynthetic template extraction and application. J. Chem. Inf. Model 59, 2529–2537 (2019).

Probst, D. & Reymond, J. L. Visualization of very large high-dimensional data sets as minimum spanning trees. J. Cheminform. 12, 12 (2020).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1388–d1395 (2021).

Mendez, D. et al. ChEMBL: towards direct deposition of bioassay data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D930–d940 (2019).

Shivanyuk, A. N. et al. Enamine real database: making chemical diversity real. Chem. Today 25, 58–59 (2007).

Zhong, Z. et al. Root-aligned SMILES: a tight representation for chemical reaction prediction. Chem. Sci. 13, 9023–9034 (2022).

Tetko, I. V., Karpov, P., Van Deursen, R. & Godin, G. State-of-the-art augmented NLP transformer models for direct and single-step retrosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 11, 5575 (2020).

Han, Y. et al. Retrosynthesis prediction with an iterative string editing model. Nat. Commun. 15, 6404 (2024).

Miyaura, N. & Suzuki, A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem. Rev. 95, 2457–2483 (1995).

Kosugi, M., Sasazawa, K., Shimizu, Y. & Migita, T. Reactions of allyltin compounds III. Allylation of aromatic halides with allyltributyltin in the presence of tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(o). Chem. Lett. 6, 301–302 (2006).

Finlay, M. R. et al. Discovery of a potent and selective EGFR inhibitor (AZD9291) of both sensitizing and T790M resistance mutations that spares the wild type form of the receptor. J. Med. Chem. 57, 8249–8267 (2014).

Cao, Q., Ma, X., Xiong, J. & Guo, P. The preparation of febuxostat by Suzuki reaction. Chin. J. N. Drugs 25, 1057–1060 (2016).

Arikawa, Y. et al. Discovery of a novel pyrrole derivative 1-[5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1H-pyrrol−3-yl]-N-methylmethanamine fumarate (TAK-438) as a potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB). J. Med. Chem. 55, 4446–4456 (2012).

Yan, C. et al. Retroxpert: decompose retrosynthesis prediction like a chemist. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 11248–11258 (2020).

Chen, S. & Jung, Y. Deep retrosynthetic reaction prediction using local reactivity and global attention. JACS Au. 1, 1612–1620 (2021).

Cui, Y., Yang, Z. & Yao, X. Efficient and effective text encoding for Chinese llama and alpaca. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08177 (2023).

Sennrich, R. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. In Proc. 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics 1, 1715–1725 (2015).

Loshchilov, I. Decoupled weight decay regularization. 7th International Conference on Learning Representations ICLR 1–18 (2019).

Loshchilov, I. & Hutter, F. Fixing weight decay regularization in Adam. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.05101 (2017).

Rasley, J., Rajbhandari, S., Ruwase, O. & He, Y. in DeepSpeed: System Optimizations Enable Training Deep Learning Models with Over 100 Billion Parameters Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining. 3505–3506 (2020).

Ya, D. et al. RSGPT: a generative transformer model for retrosynthesis planning pre-trained on ten billion datapoints. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15304009 (2025).

Ya, D. et al. RSGPT: a generative transformer model for retrosynthesis planning pre-trained on ten billion datapoints. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15336192 (2025).

Schneider, N., Stiefl, N. & Landrum, G. A. What’s what: the (Nearly) definitive guide to reaction role assignment. J. Chem. Inf. Model.56, 2336–2346 (2016).

Coley, C. W., Rogers, L., Green, W. H. & Jensen, K. F. Computer-assisted retrosynthesis based on molecular similarity. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 1237–1245 (2017).

Segler, M. H. S. & Waller, M. P. Neural-symbolic machine learning for retrosynthesis and reaction prediction. Chemistry 23, 5966–5971 (2017).

Shi, C., Xu, M., Guo, H., Zhang, M. & Tang, J. A graph to graphs framework for retrosynthesis prediction. In Proc. 37th International Conference on Machine Learning. 8818–8827 (PMLR, 2020).

Wang, X. et al. Retroprime: A diverse, plausible and transformer-based method for single-step retrosynthesis predictions. Chem. Eng. J. 420, 129845 (2021).

Chen, Z., Ayinde, O. R., Fuchs, J. R., Sun, H. & Ning, X. G(2)Retro as a two-step graph generative models for retrosynthesis prediction. Commun. Chem. 6, 102 (2023).

Sacha, M. et al. Molecule edit graph attention network: modeling chemical reactions as sequences of graph edits. J. Chem. Inf. Model 61, 3273–3284 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC no.82373718, X.W. (Xiaojian Wang)), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMs 2021-1-2M-028, X.W. (Xiaojian Wang)), and Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (No.006/2023/SKL, X.W. (Xiaojian Wang)). The computing resources were supported by biomedical high-performance computing platform, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. We thank Prof. Guang Li for his invaluable assistance in evaluating the rationality of the reactions.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Pawel Dabrowski-Tumanski, and Krzysztof Maziarz for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Deng, Y., Zhao, X., Sun, H. et al. RSGPT: a generative transformer model for retrosynthesis planning pre-trained on ten billion datapoints. Nat Commun 16, 7012 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62308-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62308-6