Introduction

The aphorism “A man can never step into the same river twice” speaks to the ever-changing nature of the world. Making sense of this dynamic reality requires the ability to generalize; that is, to extract knowledge from past experiences and apply it to new, unseen futures. Effective generalization remarkably improves the capacity of intelligent agents to adapt to rapid changes. For example, consider a child learning to ride a bike. She makes numerous attempts, falling and adjusting her balance through trial and error. Once bike riding is mastered, the child can then generalize those balancing skills to ride a scooter, allowing her to quickly master the scooter without having to learn from scratch. Given its importance to adaptive learning, generalization has been the focus of study in both cognitive neuroscience1,2,3 and machine learning4,5,6.

Recent research illustrates that representation learning is one of the cornerstones that support generalization7,8,9. Representation learning involves the transformation of raw environmental stimuli or events into robust abstract states (“state abstraction”), which summarize underlying patterns and regularities in the raw data. For example, riding a bike and scooter may be conceptually abstracted into one activity, enabling a child to realize they can transfer balancing skills previously learned from riding a bicycle to a scooter. In addition, effective representations can detect and extract a subset of the most informative and rewarding features within environments (“rewarding feature extraction”). For instance, although bicycles and scooters have distinct designs, their shared feature of having two wheels requires similar balancing skills. Historically, there has been a gap in the theoretical and comprehensive understanding of how to constitute effective representations. Bridging this gap and developing algorithms that learn generalizable representations has become a central pursuit in recent research on human cognitive neuroscience9,10,11,12 and artificial intelligence7,13,14,15,16.

This paper focuses on understanding how humans learn effective representations that enhance their generalization abilities. One influential framework for understanding human behavioral learning is reinforcement learning (RL), which views intelligent behavior as seeking to maximize expected reward17,18. This framework provides a normative understanding of a spectrum of human learning processes19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and offers theories on the underlying neural mechanisms27,28,29,30. However, by itself, the traditional RL framework provides very limited insights into human representation learning and generalization10,20,31,32,33. The framework often assumes a predefined, fixed set of task representations on which learning can operate directly, without the need for additional representation learning17. However, in real-world decision-making, humans are not provided with predefined representations. Instead, they must infer these representations from complex and dynamic environmental observations.

Here, we propose augmenting the classical RL theory to incorporate the principle of efficient coding34: while maximizing reward, intelligent agents should use the simplest necessary representations. The origin of this approach lies in the basic fact that the human brain, as a biological information processing system, possesses finite cognitive resources35. The idea of efficient use of cognitive resources has had profound impacts across many domains in psychology and neuroscience, including perception36,37,38, working memory39,40, perceptual-based generalization3, and motor control41. Furthermore, our approach aligns with Botvinick’s42 proposal that the efficient coding principle can be instrumental in understanding the representation of problems in learning and decision-making. Our work extends their proposal by concretely operationalizing efficient coding using information theory, providing a calculable measure within the RL framework, and validating this idea on human data.

Critically, our proposed approach suggests that, driven by the principle of efficient coding, an intelligent agent can autonomously learn appropriate simplified representations, which enables both state abstraction and the extraction of rewarding features, naturally resulting in generalization. To validate these predictions, we designed two experiments focusing on learning and generalization. Participants first learned a set of stimulus-action associations and were then tested on their ability to generalize to a new set of associations they had not encountered before. The first experiment investigates the emergence of state abstraction, while the second explores the extraction of rewarding features. Human participants displayed strong generalization abilities in both experiments, correctly responding to new associations without additional training. We developed a principled model based on efficient coding and demonstrated its capacity to achieve human-level generalization performance in both experiments—performance that classical RL models have not accomplished. These findings lead us to conclude that generalization is an inherent outcome of efficient coding. Given humans’ remarkable capacity for generalization, we assert that the classical RL objective augmented with efficient coding and reward maximization presents a more comprehensive computational objective for human learning.

Results

Humans exhibit two types of generalizations: perceptual-based and functional-based generalizations. Perceptual-based generalization occurs when two stimuli share a similar appearance1,38,39. Functional-based generalization, in contrast, occurs between stimuli that have similar functions (e.g. linked to the same actions), even when they do not look alike2,43,44,45,46. The latter type of generalization is more complex because it necessitates the acquisition of unseen environmental statistics before it can occur.

To investigate both types of generalization, we leveraged the acquired equivalence paradigm2,43,44. This experimental framework first links two visually distinct stimuli with identical actions, then assesses the increase in generalization between these stimuli based on their shared actions. This approach effectively establishes the functional similarity between the two stimuli, enabling a controlled experimental investigation into participants’ ability of functional-based generalization.

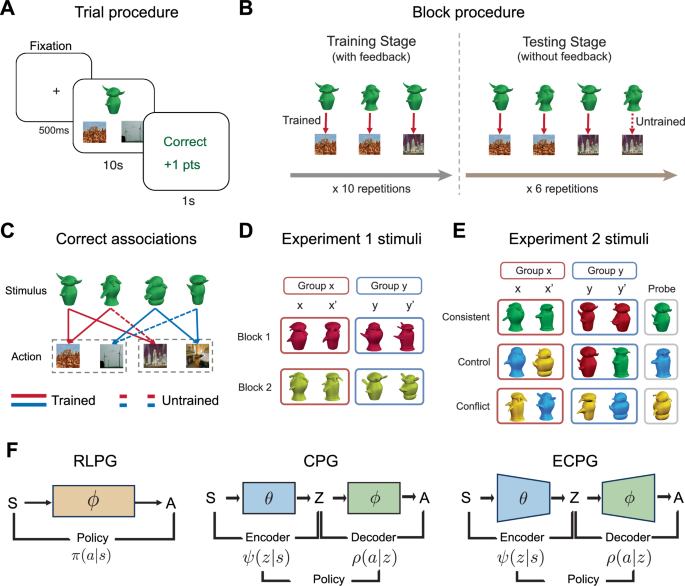

Specifically, participants performed a two-stage task. In each trial, participants were shown an alien (stimulus \(s\)) and were told that different aliens preferred to visit different locations. For a given stimulus, participants were required to choose one of two places (action \(a\)) that they believed the alien would prefer to visit (Fig. 1A). During the training stage, participants were trained on six stimulus-action associations, each repeated ten times to learn the equivalence between stimuli based on their associated actions (Figs. 1B and 1C). For example, if aliens s1 and s2 both preferred to visit a desert (a1) rather than a forest (a2), then they are equivalent and the psychological similarity of the two aliens may increase. During the training stage, participants received feedback (reward \(r\), taking a value of either 0 or 1) after every choice.

The alien stimuli were used with modifications with permission from Isabel Gauthier and Michael Tarr. Please cite85,86 as the original sources. The scene stimuli were adopted without modifications from Zhou et al.87. A One trial consists of three screens: a 500-ms fixation screen, a 10-s response screen, and a 1-s feedback screen. Each response screen displays an alien stimulus, as well as two location pictures representing different actions. B One block contains two stages. The training stage trains three associations with feedback. The testing stage tests an untrained association (dashed line) in addition to the three trained associations without feedback. C One block contains two groups, each with two stimuli. The incorrect actions of one group correspond to the correct actions of the other. The structure of the stimuli is not disclosed to participants. D Stimuli used in Experiment 1 are designed to be the same color but with different shapes and appendages to control for perceptual similarity. The four stimuli are referred to as \(x,\,{x}^{{\prime} },{y},{y}^{\prime}\), with \(x\) and \(x^{\prime}\) associating with the same actions, as do \(y\) and \(y^{\prime}\). E Stimuli used in Experiment 2. Each block contains a different type of perceptual similarity. F The model architectures. The classical reinforcement learning policy gradient (RLPG) model learns a policy that maps from stimuli \(s\) to a distribution of action \(a\). Due to the introduction of representation \(r\), the policies of the cascade policy gradient (CPG) and the efficient coding policy gradient (ECPG) model are broken into an encoder \(\psi\) and decoder \(\rho\). The ECPG and CPG model have the same architecture except that the ECPG model optimizes to use simpler representations \(z\).

In the testing stage, participants were tested on eight associations: the six trained associations plus two untrained associations that were not presented in the training stage. The untrained associations were used to evaluate people’s generalization performance. For example, if the participant learned during the training stage that \({s}_{1}\) and \({s}_{2}\) were similar to each other (had similar preferences), then participants might generalize other preferences from \({s}_{1}\) to \({s}_{2}\), even though no feedback was given about those preferences. No feedback was provided during the testing stage, and each association was repeated six times.

To quantify human generalization ability, we calculate the “untrained accuracy”, which is the response accuracy for the untrained associations that were not presented during training. The higher the untrained accuracy, the better a participant’s generalization ability. Similarly, “trained accuracy”—the response accuracy for trained associations that were presented in the training stage—serves as a measure of human learning performance. Both metrics are crucial and will be used extensively throughout this paper.

All data were collected online via Amazon Mechanical Turk.

Modeling human behavior at the computational level

David Marr47 famously argued that the human brain can be understood at three levels: the computational level, which defines the goals to be achieved; the algorithmic level, which details the specific algorithms the human brain used to reach these goals; and the implementational level, which describes how these algorithms are physically realized. In psychology and cognitive science, researchers often build models at the algorithmic level. They typically postulate specific cognitive mechanisms within the human brain, describe these mechanisms using computer programs, and demonstrate their explanatory power over human behavioral data45,46,48.

However, the question of whether the human brain reconstructs efficient representations for task stimuli is situated at the computational level. Therefore, we need to construct models at this same level. In concrete, we formalized our hypotheses—with or without efficient coding—as distinct computational goals, each addressed using the simplest possible algorithm. Unlike algorithmic-level models, computational-level models do not presume specific mechanisms; Instead, these mechanisms naturally emerge during the process of achieving the defined computational goal. Thus, computational-level models not only explain human behaviors but also shed light on the potential cognitive mechanisms underlying these behaviors, thereby demonstrating superior explanatory power over algorithmic-level models.

We built three computational-level models. First, we established a classical RL baseline, named Reinforcement Learning Policy Gradient (RLPG; see Fig. 1F and “Method-Models-RLPG”), which assumes that humans do not learn simplified representations. The computational goal is formulated as follows:

$$\max_\pi {E}_{\pi }\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]$$

(1)

where \(\pi ({a|s})\) is a policy that maps a stimulus, \(s\), to a distribution of actions, \(a\). On each trial, an agent had to choose between two possible actions, each with a 50% chance of being correct. Prior to making a decision, the agent was expected to have a baseline reward expectation of \(b\) = 0.5. This baseline was used to evaluate the “goodness” of the actual reward received. A reward was considered positive if it exceeded the agent’s expectation, otherwise negative. The RLPG model interpreted human behavior as involving the search for the policy that yielded the greatest reward (above the baseline) in the process of interacting with the environment.

Second, we developed an Efficient Coding Policy Gradient model (ECPG; Fig. 1F and “Method-Models-ECPG”), which posits that humans learn simpler representations through efficient coding. The challenge in modeling this principle lies in defining the complexity (or simplicity) of representations. Recent studies on human perception have conceptualized perception as an information transmission process, where an encoder transmits environmental sensory signals (\(s\)) into internal representation (\(z\))3,39,40. These studies measure the complexity of representations by the amount of information transmitted by the encoder, quantified by the mutual information between stimuli and representations \({I}^{\psi }({S;Z})\). Based on these works, the computational goal of efficient coding is formalized as maximizing reward while minimizing the representation complexity,

$${\max}_{\psi,\rho}{E}_{\psi,\rho }\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]\,-\lambda {I}^{\psi }\left({S;Z}\right)$$

(2)

The critical parameter \(\lambda \ge 0\), referred to as the simplicity parameter, controls for the tradeoff between the classical RL objective and representation simplicity. When \(\lambda\) = 0, the agent does not compress stimuli representations for simplicity, and the efficient coding goal reduces to the RL goal. Conversely, as \(\lambda \to \infty\), the agent learns the simplest set of representations, encoding all stimuli into a single, identical representation. Therefore, the optimal \(\lambda\) should be a moderate value, balancing compressing without oversimplification. Due to the introduction of latent representation \(z\), the policy needs to be broken down into an encoder, \(\psi\), and a decoder, \(\rho\), which are simultaneously optimized according to Eq. 2 (Fig. 1F).

To test whether humans learn compact representations, the establishment of the RLPG and ECPG models would typically be sufficient, because the contrasting hypotheses they represent (RLPG stands for “No”, ECPG stands for “Yes”) together cover the entire hypothesis space. One concern, however, is that the introduction of the representation in ECPG has changed the model architecture, potentially introducing confounding factors. To control these confounders, we implemented a third model, Cascade Policy Gradient (CPG; “Method-Models-CPG”), which also supports the non-efficient coding hypothesis. The CPG is a special case of the ECPG model which sets the simplicity parameters to 0 (\(\lambda\) = 0 in Eq. 2) (Fig. 1F),

$${\max}_{\psi,\rho} {E}_{\psi,\rho }\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]$$

(3)

This model serves as an intermediary between the RLPG and ECPG models, optimizing for the classical RL objective while concurrently updating the representations.

To ensure that observed behavioral differences result only from optimizing different computational goals, we carefully controlled for all other model components. First, all three models address their computational goals using the same policy gradient approach, where models explicitly learn and maintain a parameterized policy17,49. The method was selected over the more commonly used value function approach in psychology and neuroscience because it introduces a minimum number of parameters, therefore better distilling the computational essence of each computational goal. Second, the three models were initialized to (nearly) the same state. Due to the distinct appearances of stimuli in the experiments, we pretrained the encoders of the CPG and ECPG models to achieve a 99% initial discrimination accuracy among the four stimuli (see “Method-Pretrain an encoder”). We chose a threshold of 99% instead of 100% for two reasons: first, to model the perceptual noise present in the human visual system, and second, to prevent gradient vanishing, which is an engineering concern. The RLPG model implicitly assumes perfect discrimination between stimuli and, therefore, does not require the same pretraining as others. Lastly, we used the same model fitting method for all three models, fitting the parameters to each participant separately using maximum-a-posteriori (MAP) estimation (“Method-Model fitting”), based on behavioral data from both the training and the testing stages.

In the following sections, we demonstrate that, at the computational level, only the ECPG model—which incorporates representation simplification—can qualitatively account for human generalization behaviors. We also compare the ECPG model to several published algorithmic-level models and show that, even without presuming any specific algorithmic details about cognitive mechanisms, the ECPG model surpasses models with handcrafted cognitive mechanisms in describing human behavior. Overall, our findings show that integrating efficient coding into the classical RL objective provides a more comprehensive computational framework for understanding human learning and generalization.

Abstract states inevitably merge in simplified representations, resulting in generalization

Experiment 1 studies human generalization using the standard acquired equivalence paradigm. In this setting, the four alien stimuli within each block share the same color but differ in shapes and appendages (Fig. 1D). This design allows us to specifically study functional-based generalization, because the perceptual features (color, shape, and appendage) provide no cues for generalization.

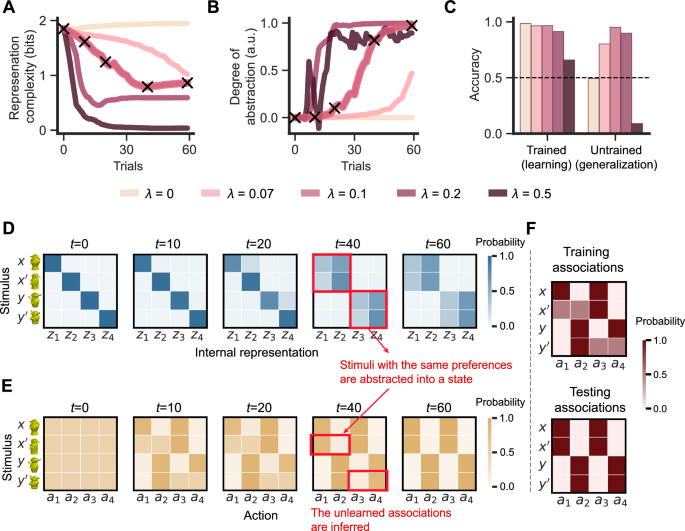

Why can humans generalize? The proposed efficient coding principle posits that, to achieve simplified representations, an agent must appropriately abstract environmental stimuli into robust latent states. Within each of these abstract states, the stimuli can then mutually generalize. To illustrate this, we simulated the ECPG model at different levels of simplicity, controlled by the parameter λ (0, 0.07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5), while keeping other parameters constant (See simulation details in “Method-Simulation”). Note that when \(\lambda\) = 0, the ECPG model reduces to the CPG model, which does not employ efficient coding.

The simulations first demonstrate that efficient coding drives state abstraction. As shown in Fig. 2A (\(\lambda\) = 0.1), representation complexity decreases significantly from the beginning of training (t = 0) to the end (t = 60). This representation simplification significantly affects the model’s internal representations (\(\lambda\) = 0.1). Before training, when representations are complex, each stimulus is encoded in an unstructured way, with a one-to-one correspondence in representation space (Fig. 2D, t = 0). Driven by efficient coding, the ECPG model compresses representations, discarding redundant information and mapping stimuli associated with the same actions into similar representations, forming abstract states (Fig. 2D, t > 20, red arrows). We quantify the degree of the state abstraction using the Silhouette score50, which measures an object’s (\(x\)) similarity to its own latent state (\(x^{\prime}\)) relative to other states (\(y\) and \(y^{\prime}\)). A score close to 0 indicates poor abstraction, while a score close to 1 indicates strong abstraction—stimuli within each abstract state (\(x\) and \(x^{\prime}\)) are encoded similarly and associate with each other, while stimuli across abstract states (\(x\) and \(y\)) remain distinct. Figure 2B (\(\lambda\) = 0.1) shows the Silhouette score increasing from 0 toward 1, indicating emergence of stable, meaningful abstract states from the initially unstructured set of representations. The stimuli shared the same preferences became associated with each other.

A–E are generated by averaging over 400 simulations. A Representation complexity \({I}^{\psi }({S;Z})\) throughout the training process. The cross makers at t = 0, 10, 20, 40, 60 indicate the trials that are sampled for detailed analysis. B Throughout the training process, the effectiveness of state abstraction is measured by the silhouette score. C The proportion of correct responses for associations that were presented (trained) and not presented (untrained) during the training stage reflects learning and generalization performance, respectively. This figure includes only data from the testing stage. Dashed lines represent the 50% chance level. D Encoders \(\psi ({z|s})\) with \(\lambda\) = 0.1 at the sampled training trials. An encoder maps a stimulus \(s\in \{x,{x}^{{\prime} },x,y^{\prime} \}\) to a distribution of internal representations \({z}_{1}\) - \({z}_{4}\). Each row stands for a categorical distribution that sums to 1. Darker shades indicate higher probability values. See Supplementary Note 1.2 for encoders for other \(\lambda s\). E Policies \(\pi ({a|s})\) with \(\lambda\) = 0.1 at the sampled training trials. A policy maps a stimulus \(s\in \{x,{x}^{{\prime} },x,y^{\prime} \}\) to a distribution of actions \({a}_{1}\) - \({a}_{4}\). In each row, actions (\({a}_{1}\), \({a}_{2}\)) and (\({a}_{3}\), \({a}_{4}\)) form a probability distribution. See Supplementary Note 1.2 for policies for other \(\lambda s\). F Predefined correct associations in the training and testing stages. The dark tiles indicate the correct associations, and the pink tiles stand for the associations not shown to the participants.

We further show that stimuli within the same abstract state can generalize to each other. After abstract states stabilize (t > 40), the model begins to decode policies from the structured representations, and changes in representation complexity become more nuanced (Fig. 2A, \(\lambda\) = 0.1). Policies decoded from stimuli within the same abstract state are similar (Fig. 2E, red arrows), illustrating the ECPG model’s ability to generalize from training to testing associations. This is reflected by the model’s significantly above-chance untrained accuracy (Fig. 2C, \(\lambda\) = 0.1), despite being exposed to only a subset of the associations during training (Fig. 2F). Similar results can be observed when \(\lambda\) is set to 0.2 (Supplementary Note 1.2).

Note that the degree of state abstraction is critical; both insufficient and excessive abstraction impair generalization. As \(\lambda\) increases, the model prioritizes representation simplification over reward maximization, resulting in more intense and rapid abstraction (Fig. 2A). For lower \(\lambda\) (0 or 0.07), the ECPG model becomes more reward-focused and exhibits little or no reduction in representation complexity (Fig. 2A, \(\lambda\) = 0.07 and 0). The insufficient compression prevents the model from associating stimuli that share the same actions, leading to a failure in state abstraction (Fig. 2B, \(\lambda\) = 0.07 and 0) and, consequently, compromised generalization performance (Fig. 2C, \(\lambda\) = 0.07 and 0). Conversely, overly compressed representations (Fig. 2A, \(\lambda\) = 0.5) tend to oversimplify abstraction, assigning all stimuli to a single internal state. This results in significant reward loss and unstable state abstraction, as reflected by the oscillating Silhouette score (Fig. 2B, \(\lambda\) = 0.5). Such oversimplified abstraction can be detrimental to both generalization and learning performance (Fig. 2C, \(\lambda\) = 0.5).

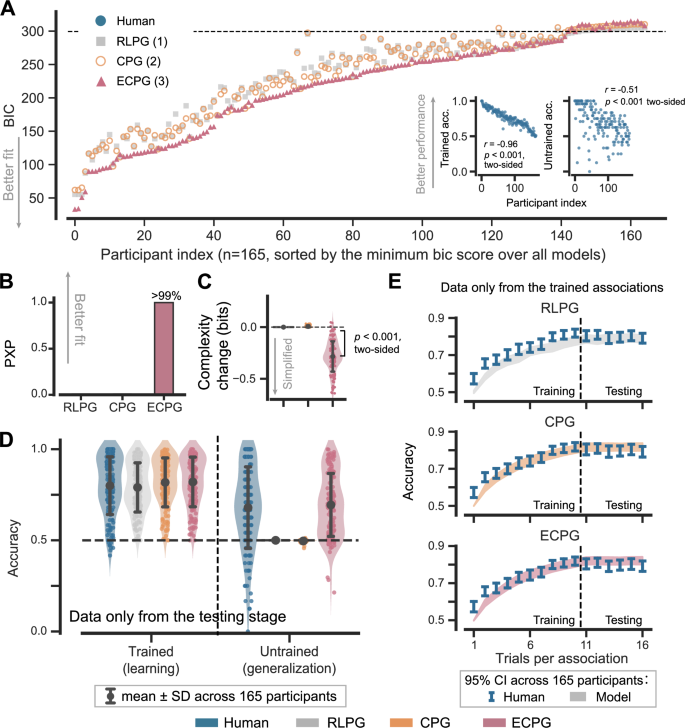

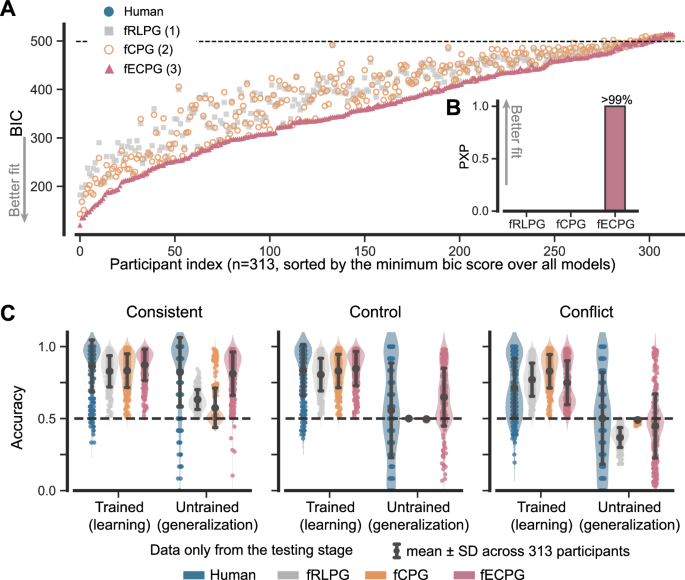

So far, our theoretical framework has outlined how efficient coding could result in functional-based generalization. To verify whether these principles in humans, we collected behavioral data from 165 participants performing two blocks of the standard acquired equivalence task. We fitted all three models to the data and evaluated them using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The ECPG model best described the majority of participants (Fig. 3A), with a stronger advantage in the testing stage, where generalization occurs (Table 1). Some participants’ behaviors were poorly captured by the ECPG model, primarily due to their low effort, which resulted in poor learning (Pearson’s r(165) = −0.96, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.97, −0.94]) and generalization performance (Pearson’s r(165) = −0.52, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.63, −0.40]). We also conducted a Bayesian group-level comparison and reported the protected exceedance probability (PXP)—the probability that a model accounts for the data better than the others, beyond the chance level (the log model evidence was estimated using the BIC)51. As expected, the ECPG model again was ranked first among the three models (PXP > 0.999; Fig. 1B). These findings underscore the unique capability of the ECPG model in capturing human learning and generalization performance.

Models were fit to all behavioral data of each participant in both training and testing stages. A Models’ Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each participant. The RLPG model has 1 parameter, the CPG model has 2 parameters, and the ECPG model has 3 parameters. Also, see Table 1 for the exact value. B Protected exceedance probability (PXP) tallies for each model. C Change in representation complexity after training. Scatterplot data located above the horizontal dashed line indicate representation expansion, while those below the line indicate representation compression. The RLPG model assumes that environmental stimuli are always perfectly reconstructed and, therefore, yield no change in complexity. Error bars reflect the mean ± standard deviation (SD) across 165 valid participants. D Proportion of correct responses for trained and untrained associations in the testing stage, representing learning and generalization performance, respectively. Only data from the testing stage is included. The dashed lines indicate the 50% chance level. Error bars reflect the mean ± SD across 165 valid participants. E Proportion of correct responses over the number of trials for each association. The dashed line splits the experiment into two stages: on the left is the training stage, and on the right is the testing stage. Data from untrained associations is excluded from this learning curve analysis. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the mean across 165 human participants, while the shaded areas represent the 95% CI of the mean for the corresponding model simulations.

To show that only the ECPG model learns simplified representations, we computed the change in representation complexity during training, which was quantified as the difference in the mutual information \({I}^{\psi }({S;Z})\) before and after training (Fig. 3C). The ECPG model successfully reduced complexity, indicating that it learned simplified representations as expected. In contrast, the two control models did not compress their representations. Furthermore, we examined the simplicity parameter \(\lambda\) of the ECPG model and found it to be significantly greater than 0 (two-sided t(164) = 4.29, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.33, 95% CI = [0.11, 0.29]) (see Supplementary Note 1.1 for model parameters). This finding suggests that the representation simplification plays an important role in capturing human behaviors.

Human participants generalized effectively. Despite receiving no training, the untrained accuracy for human participants is significantly greater than the 50% chance level, though slightly lower than trained accuracy (Fig. 3D, blue). This observation, consistent with many prior studies2,43,44, indicates that human participants effectively generalized from prior learning. The ECPG model closely captures this generalization phenomenon, whereas the two control models cannot generalize at all, with the untrained accuracy remaining at the 50% chance level (Fig. 3D, gray and orange). More importantly, the ECPG model’s strong performance in capturing human generalization did not compromise its explanatory power for human learning behavior. It offers a description as precise as that of the two control models concerning the human learning curve throughout the training stage (Fig. 3E).

Based on both quantitative and qualitative evidence, we conclude that humans’ ability to generalize originates from their computational goal of efficient coding. This process promotes the emergence of abstract latent states, which form the foundational basis for generalization.

Efficient coding automatically extracts rewarding features throughout learning simplified representations

Experiment 2 extended the standard paradigm to examine both functional-based and perceptual-based generalizations in humans. The experiment featured two primary modifications. First, we manipulated the stimuli’s perceptual cues--shape, color, and appendage--to ensure each feature provided a different amount of information about the environment’s rewards. We designed three experimental conditions, each with a distinct rewarding configuration (Fig. 1E):

-

In the consistent condition, the alien stimuli with the same color were associated with the same actions, making the color the most rewarding feature.

-

In the control condition, the colors of the stimuli were mutually different, and all features were equally rewarding. This condition, like Experiment 1, only tested the functional-based generalization and the state abstraction ability of an agent.

-

In the conflict condition, stimuli with the same color were associated with different actions, making shapes and appendages the rewarding features, while the color cue yielded a negative reward.

These three conditions also indicated three levels of difficulty in rewarding feature extraction. In the consistent and conflict condition, the four stimuli shared two colors, making color cues more frequent and salient. For example, while the “cylinder” shape was associated with rewards twice during training, the color “red” might have been rewarded four times. The consistent condition was the easiest because this salient feature yielded positive rewards, while the conflict condition was the most difficult because the agent needed to first suppress the color cue, the salient feature, before being able to detect rewarding ones.

The second primary modification in Experiment 2 was the incorporation of a probe stimulus during the testing stage; this stimulus was entirely new and had not been encountered during training. This probe was used to assess humans’ ability to extract informative and rewarding features at a behavioral level. A more detailed introduction to the use of this probe design follows below, along with the presentation of our model’s predictions. All other aspects of the experiment remained identical to those in Experiment 1.

We reused the three models in Experiment 1, only adding a feature embedding function to encode perceptual information. Each of the three visual features was encoded into a five-dimensional one-hot code, where each dimension indicated a specific feature value. For example, the shape “cylinder” was [1, 0, 0, 0, 0], the color “purple” was [1, 0, 0, 0, 0], and the color “yellow” was [0, 1, 0, 0, 0]. Each stimulus was represented by a combination of three such codes, concatenated into a 15-dimensional vector to form the model’s input. We refer to the models used in Experiment 2 as feature RLPG (fRLPG; “Method-Models-fRLPG”), feature CPG (fCPG; “Method-Models-fCPG”), and feature ECPG (fECPG; “Method-Models-fECPG”) models to highlight their integration of the feature embedding construct.

To evaluate the model’s feature extraction ability, we analyzed the importance assigned to each feature by perturbing one feature dimension and measuring changes in representations52,53. A larger change in the representations indicated a higher feature importance (see “Method-Perturbation-based feature importance”). Therefore, in this experiment, if a model consistently assigns more importance to the predefined rewarding perceptual cue across all three conditions, we conclude that this model can effectively detect and extract rewarding features.

Now that the stage is set, we can focus on answering three central research questions. First, does the principle of efficient coding drive a model to extract rewarding features? Second, if so, how can we validate that humans follow this principle in their learning processes? Third, how does the rewarding feature extraction interact with the state abstraction ability examined in Experiment 1?

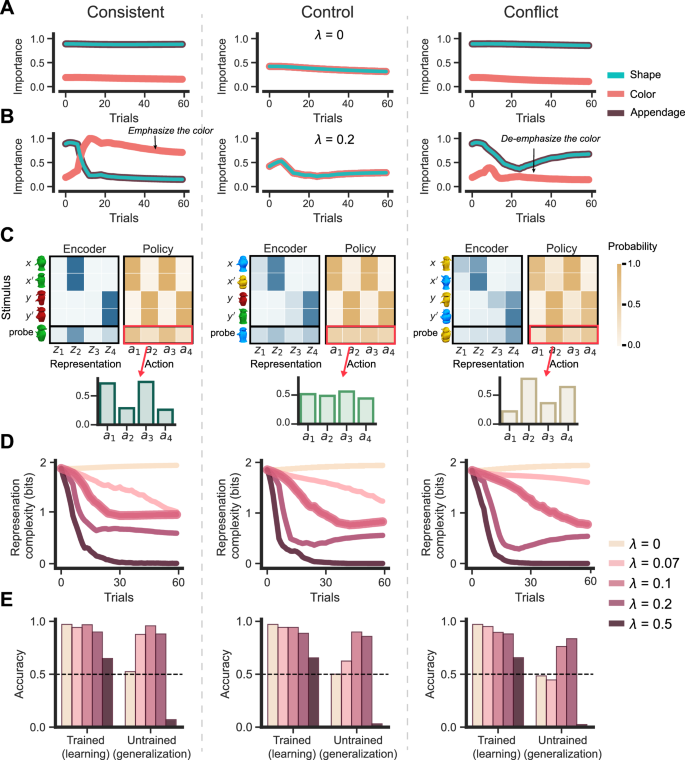

For the first question, we ran stimulations and showed that efficient coding does promote reward feature extraction. As designed in the experiment, color served as the rewarding feature in the consistent condition, while it yielded negative rewards in the conflict condition. Driven by the need for simpler representations—reflected in a focus on fewer features—the fECPG model (\(\lambda\) = 0.2) must selectively assign more importance to the color cue in the consistent case; and less importance when the color becomes unrewarding (Fig. 4B, consistent). Conversely, in the conflict condition, the model had to first deemphasize the salient cue color, due to its negative rewards, and then reallocate importance to the other features contributing to positive rewards (Fig. 4B, conflict). The demand for simplicity drives the model to focus on a subset of features, and the goal of maximizing reward ensures that these focused features must be rewarding. In contrast, a model without efficient coding (\(\lambda=0\)) cannot adaptively reallocate feature importance during its interaction with the environment. The model exhibits nearly the same feature importance assignment for both consistent and conflict cases (Fig. 4A), indicating its inability to detect rewarding information. It is worth noting that the fECPG model unintuitively predicts that shape and appendage are rewarding features before training. We believe this is caused by our simplistic approach to encoder initialization. We will further elaborate this point in the discussion section. However, this observation does not undermine our conclusion.

All panels are generated by averaging over 400 simulations. A Simulated feature importance along with training of the fECPG model with \(\lambda\) = 0, which collapses to the fCPG model. Note that the “shape” and “appendage” curves always overlap. B Simulated feature importance along with training of the fECPG model with \(\lambda\) = 0.2. C The predictive “probe” representation and policy of the fECPG agent (\(\lambda\) = 0.2) at the end of the training stage. An encoder maps a stimulus \(s\in \{x,{x}^{{\prime} },x,y^{\prime} \}\) to a distribution of internal representations \({z}_{1}\) - \({z}_{4}\), and a policy maps a stimulus \({s}\in \{x,{x}^{{\prime} },x,y^{\prime} \}\) to a distribution of internal representations \({a}_{1}\) - \({a}_{4}\). Darker tiles denote higher values. The policies for the control and conflict conditions are more stochastic than are those in the consistent condition. The predictive policies applied to the probe stimuli are visualized in both a heatmap and a bar plot. D Representation complexity throughout learning. E Learning and generalization performance for the fECPG model with different levels of simplicity, λ = 0, 07, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5.

To address the second question, we adopted a “probe” design. The probe stimulus, introduced only during the testing stage and not present in the training, was designed to always share the same color as stimulus \(x\) and the same shape as stimulus \(y^{\prime}\). In the consistent condition, where color was the most important feature, the probe stimulus should be perceived as similar to stimulus \(x\) (Fig. 4C, consistent, encoder), leading to a response that coincides with the one for stimulus \(x\) (Fig. 4C, consistent, policy). In this scenario, it is expected that human participants will demonstrate a higher preference for actions \({a}_{1}\) and \({a}_{3}\) when responding to the probe stimuli. Conversely, in the conflict condition where color was neglected, the probe stimulus should be perceived as more similar to stimulus \(y^{\prime}\) (Fig. 4C, conflict, encoder), which should be also reflected in the response (Fig. 4C, conflict, policy). Therefore, human participants would be likely to use \({a}_{2}\) and \({a}_{4}\). In the control condition, given the lack of a dominant rewarding feature, the response to the probe stimulus should not show a strong preference, being distributed between those for stimuli \(x\) and \(y^{\prime}\) (Fig. 4C, control, policy).

For the third question, we observed that the efficiency of rewarding feature extraction extends or shortens the time it takes to form stable abstract states, influencing the agent’s learning and generalization. In the consistent condition, the fECPG model rapidly identified the rewarding feature and formed stable abstract states (Fig. 4D, consistent), enabling a high degree of generalization (Fig. 4E, consistent). However, in the control condition, where no salient cue dominates, the model experienced a slower state abstraction process (Fig. 4D, control). In the conflict condition, the need to suppress color prolonged the time required to extract rewarding features, thereby further extending the state abstraction period (Fig. 4D, conflict). Consequently, the time available for policy decoding was reduced, resulting in poorer learning and generalization performance in the conflict case (Fig. 4E, control, conflict).

To validate these model predictions, we collected behavioral data from 313 participants who each completed three task blocks corresponding to consistent, control, and conflict conditions. We fit all three feature-based models and found that both BIC and PXP preferred the fECPG model as the best model for capturing human behavioral data, consistent with the findings from Experiment 1 (Fig. 5A, B and Table 2).

Models were fit to all behavioral data of each participant in both training and testing stages. A Models’ Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each participant. The fRLPG model has 1 parameter, the fCPG model has 2 parameters, and the fECPG model has 3 parameters. The BICs for a fully random policy are represented by dashed lines. Participants with lower BIC scores generally exhibit better learning and generalization performance. See Table 2 for the exact value. B Protected exceedance probability (PXP) tallies for each model. C Learning and generalization performance of human participants and models for each experimental condition. Dashed lines indicate the 50% chance level. Only data from the testing stage is included in the analysis. Error bars reflect the mean ± SD across 313 valid participants.

More importantly, as the principle of efficient coding predicts, human participants exhibit different levels of generalization across experimental conditions. They achieved high untrained accuracy in the consistent condition, lower in the control condition, and lowest in the conflict condition (Fig. 5C, blue). Beyond the overall trend, humans’ generalization behaviors are also characterized by high variability. Some participants generalized effectively across all conditions, while others always negatively transferred their knowledge. This variability is also accurately captured by the fECPG model (Fig. 5C, red), but not by the two classical RL models without efficient coding (Fig. 5C, gray and orange).

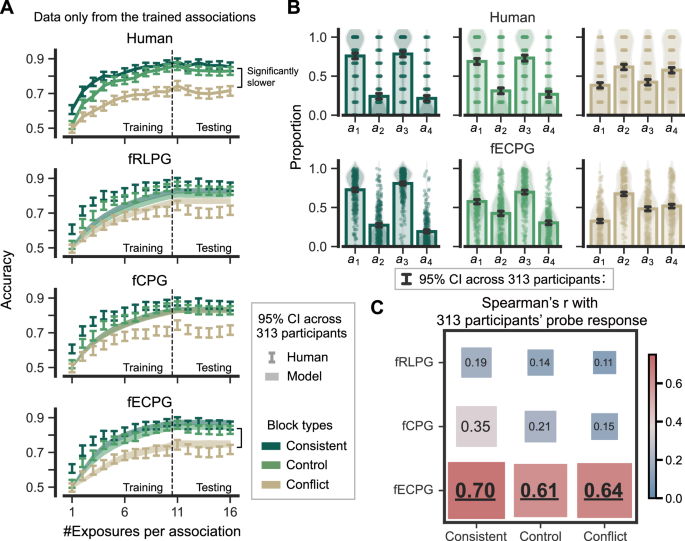

To our surprise, the ECPG model shows a significant advantage in predicting human learning performance—an area where classical RL models have traditionally been preferred. Participants demonstrated a more rapid improvement in the consistent condition than in the control and conflict conditions. Specifically, the learning curve in the conflict condition was markedly slower when compared to the other conditions. Only the fECPG model captured the significantly slower trend (Fig. 6A).

Models were fit to all behavioral data of each participant in both training and testing stages. A Proportion of correct responses over the number of times that each association is shown. Dashed lines split the experiment into training and testing stages. The analysis excludes responses to the untrained associations and the probe stimulus. Error bars represent the 95% CI of the mean across 165 human participants, while the shaded areas represent the 95% CI of the mean for the corresponding model simulations. B Humans and the fECPG model respond to the probe stimuli. Error bars indicate the 95% confidence interval for the mean estimate. C Correlation between model predictions and human responses to probe stimuli. The annotated value represents Spearman’s correlation coefficient under different experimental conditions. The bold values highlight the highest correlation under each specific learning condition.

The probe design further validated the human participant’s ability to extract rewarding features as predicted by the efficient coding principle. Human participants’ responses to the probe stimuli were consistent with the fECPG model predictions (Fig. 6B, C; Spearman’s r > 0.60, p < 0.001 for all conditions; see “Method-Correlation between humans’ and models’ probe response” for the correlation calculation). In contrast, models without efficient coding, fRLPG and fCPG, failed to replicate such behavioral patterns (see Supplementary Note 1.5 for their probe responses), exhibiting significantly weaker correlations with human behavioral data (Fig. 6C).

It is important to note that there is a discrepancy between our prediction and human behavior in the control condition. Human participants were likely to use the policy of stimulus \(x\) rather than a random policy in response to the probe. This phenomenon could have arisen from two potential factors. First, during training, the experiment might not have adequately balanced the presentation frequency of the stimuli. Participants learned two associations with stimulus \(x\) and one with stimulus \(y^{\prime}\) (with the other association tested in the testing stage), which implies that stimulus \(x\) was shown twice as frequently as was stimulus \(y^{\prime}\). Consequently, participants might have adaptively adjusted their encoding and decision-making on these statistics and placed more attention on stimulus \(x\). Second, the color feature might have been inherently more salient to humans. When the three features were equally informative, participants may have naturally prioritized the color feature. However, this gap does not undermine our conclusion that the fECPG model best captures human participants’ responses to the probe stimulus.

All evidence leads to one conclusion: during learning, humans strive to distill representations into their simplest and most essential forms. Driven by this goal, humans learn representations using a small subset of rewarding features within their environments. They further simplify these representations by abstracting them into compact, lower-dimensional internal states, which naturally leads to generalization.

The human brain optimizes efficient coding to enhance learning and generalization

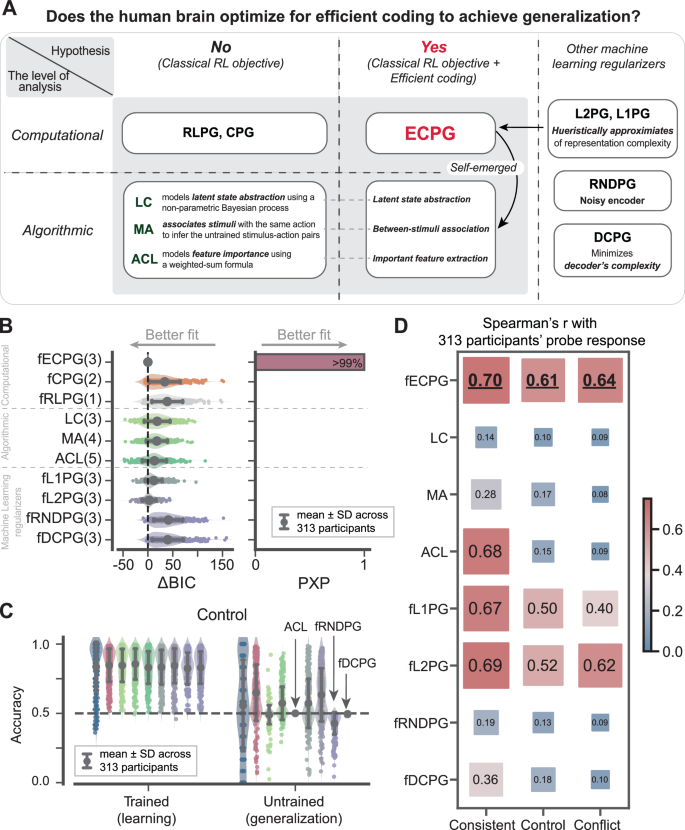

A potential argument is that the classical RL objective is still sufficient to explain human behavior once it is augmented with cognitive mechanisms at the algorithmic level. We oppose this view for two reasons. First, a range of current algorithmic-level models fail to capture human behaviors as effectively as the ECPG model (as detailed below). Second, the mechanisms embedded in these models inherently simplify representations, essentially pursuing efficient coding.

We developed and compared three algorithmic-level models (Fig. 7A). The first model, the Latent Cause model45,46,54,55 (LC; “Method-Models-LC”) employs a hierarchical nonparametric Bayesian process to simulate human state abstraction. During the learning period, the LC model categorizes observed stimuli into latent clusters and learns the decision policy for these clusters. The second model, called the Memory-Association model (MA; “Method-Models-MA”), memorizes all stimuli and their preferred actions, establishing associations between stimuli that share the same actions. These associations facilitate the inference of correct actions in untrained tasks, thereby enabling generalization. The third model, Attention at Choice and Learning48,56,57 (ACL; “Method-Models-ACL”) learns the value of each feature and calculates the feature importance based on these values. The model uses a linearly weighted feature value for decision-making. Notably, the LC and MA models emphasize state abstraction ability, whereas the ACL model is designed to extract and prioritize rewarding features. Both abilities could emerge by optimizing for the efficient coding goal, but in a different computational formulation.

A An overview of models across hierarchical levels. The central research question explores whether the human brain optimizes for efficient coding to enhance generalization. At the computational level, the ECPG model affirms this hypothesis (“Yes”), whereas the RLPG and CPG models represent the opposing viewpoint (“No”). These models collectively represent the entire hypothesis space at the computational level. Below this, the ECPG model is contrasted with various algorithmic-level models (LC, MA, ACL), each designed with specific cognitive mechanisms. Additionally, the ECPG model is compared against several common machine learning regularizers (L2PG, L1PG, DCPG) that also aim to reduce model complexity, but through different methods. B Model comparisons for all models in terms of BIC and PXP in Experiment 2. Error bars reflect the mean ± SD across 313 participants. Refer to Supplementary Note 1.3 for the model comparison in Experiment 1. Additionally, see Supplementary Note 3 for an analysis of why other models perform worse in fitting. C Learning and generalization performances across all models in the control case of Experiment 2. Error bars reflect the mean ± SD across 313 participants. See Supplementary Note 1.4 for generalizations in other conditions. D Correlation between model predictions and human responses to probe stimuli at different experimental conditions. See Supplementary Note 1.5 for the bar plots. The bold values highlight the highest correlation under each specific learning condition.

We tested these algorithmic-level models on Experiment 2, with a focus on two qualitative metrics: generalization in the control case to examine their latent cause abstraction ability (Fig. 7C) and response to probe stimuli to evaluate their rewarding feature extraction (Fig. 7D). All three models underperformed the fECPG model in terms of BIC and PXP (Fig. 7B, Table 2). The LC and MA models failed to account for human responses to probe stimuli (Fig. 7D) due to lacking feature extraction mechanism. The ACL model struggled with generalizing in the control case (Fig. 7C) as well as extracting rewarding features in both the control and conflict cases (Fig. 7D), because its feature importance calculations cannot deemphasize the negatively-rewarded feature effectively (see Supplementary Note 3.2 for further discussion). These results underscore the superior performance of the fECPG model, a computational-level model, in modeling human behaviors and support our hypothesis that human participants learn simplified representations when maximizing rewards.

From a machine learning perspective, the fECPG model proposed here defines a regularized optimization objective. This raises a final question: can the efficient-coding term be substituted by other commonly used machine learning regularizers? We implemented an L1-Norm Policy Gradient (L1PG; “Method-Models-L1PG, L2PG, and DCPG”) and an L2-Norm Policy Gradient (L2PG), incorporating L1 or L2 norms as heuristic approximations for representation complexity. While the L1PG model underperformed, the L2PG model showed comparable performance to fECPG (Fig. 7B, C, and D). Although a substantial portion ( ~ 36%) of participants were better described by the L2PG model, these participants displayed distinct behavioral dynamics: compared to participants better captured by the fECPG model, they tended to learn more slowly and showed weaker generalization (see Supplementary Note 3.3 for further details). This suggests that the ECPG model has a unique capability in capturing humans’ fast learning and strong generalization patterns. For completeness, we also tested a Random Regularizer Policy Gradient (RNDPG; “Method-Models-RNDPG”), which injects noise into the encoder weights58, as well as a Decoder Complexity Policy Gradient (DCPG), which constrains decoder complexity. However, both models failed to generalize in the control condition or extracting rewarding features (Fig. 7B, C, D).

Finally, we validated our conclusions by performing a model recovery analysis to test our ability to differentiate between models (Supplementary Note 1.6). Importantly, we found that the ECPG model can be uniquely distinguished from the other models. The low false positive rate (with other models unlikely to be misidentified as ECPG) indicates that the ECPG model’s superior performance over the control models is not due to its expressiveness but to its accurate description of human behavior. Thus, these findings support our conclusion that the ECPG model, with its efficient coding-augmented RL objective, best accounts for human learning and generalization.

Discussion

The classical RL framework has limitations in terms of its ability to explain human representation learning and generalization. In this paper, we proposed augmenting the classical RL objective with the efficient coding principle: an intelligent agent should distill the simplest necessary representations that enable it to achieve its behavioral objectives. A computational-level model derived from the revised framework (Efficient Coding Policy Gradient; ECPG), predicts that an intelligent agent automatically learns to construct representations with a small set of rewarding features with the environment. These representations are further simplified by abstracting them into compact, lower-dimensional internal states, which naturally results in generalization. These predictions were validated in two behavioral experiments, where the ECPG model consistently provided a more accurate description of human behavior than two classical RL models without efficient coding as well as several published human representation learning models. These findings indicate that efficient coding offers a more suitable computational objective in understanding human behavior.

In this paper, we examine whether the classical RL objective alone, or in combination with efficient coding, better aligns with Marr’s computational level in explaining human behavior. A potential critique of our approach in section “The human brain optimizes efficient coding to enhance learning and generalization” is the lack of comparison with an alternative model capable of generalizing without representation simplification. However, we found no such model in the existing literature. This absence reflects the historical context of the acquired equivalence paradigm on which our study builds. Although generalization within this paradigm has long been documented59, previous explanations—including categorization60, stimulus association2, and selective attention61—are all encompassed by our efficient coding framework. In other words, algorithmic models based on selective attention, for example, inherently implement mechanisms predicted by the computational-level goal of efficient coding.

Previous research using the acquired equivalence paradigm has demonstrated that people with schizophrenia62,63, mild Alzheimer’s disease64, hippocampal atrophy43, and Parkinson’s disease43 exhibit dysfunction in performing acquired equivalence task. Despite these findings, the neurocognitive mechanisms underlying these impairments remain incomplete understanding. The ECPG model, which provides a detailed computational representation of human learning and generalization within this paradigm, may offer a framework for investigating the cognitive and neural processes underlying these cognitive anomalies. However, this potential application of the ECPG model remains untested and requires empirical validation through experimental studies.

Beyond serving as a better empirical model for human learning, the proposed computational objective could potentially represent a rational strategy (specifically, a resource-rational strategy; see below) for humans. The classical RL objective was designed to maximize expected reward in narrowly defined settings, where agents focus on learning a single, well-defined task17. However, humans live in more complex and dynamic real-world environments, where decision-making requires agents to generalize effectively from past experiences to earn rewards in unseen scenarios. Moreover, the human brain is innately capacity-constrained35; it has inherent limitations in processing and storing information, which requires the efficient use of cognitive resources. Therefore, learning simpler representations that facilitate generalization is a crucial component in the pursuit of maximizing reward in real-world decision-making. We believe that this insight can also improve learning and generalization in artificial intelligence operating under real-world conditions.

The idea of linking RL to efficient coding has been applied to understand learning and generalization in various contexts22,42,65,66,67,68,69. For example, this approach has been shown to better explain monkeys’ neural activity in frontal areas65, humans’ risky choice behavior67, and meta-level generalization between tasks66. Here, we present a specific formalization of efficient coding using information-theoretic measures. We demonstrate that this approach provides a better empirical description of both human learning and generalization behaviors compared to several alternatives.

Our study also helps bridge the gap between representation learning in the human brain and machine learning. In cognitive science, researchers have applied latent cause clustering (LC) and Association-Choice Learning (ACL) models to understand a variety of phenomena9. Latent cause clustering can explain Pavlovian conditioning and extinction55, memory modification54, social classification70, and functional-based generalization45,46,71. Selective attention, on the other hand, has been used to explain concept formation72, the evolution of beliefs73, and has received neural evidence from eye-tracking and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) studies48,56. In machine learning, researchers have focused on how information-theoretic regularizers facilitate an artificial agent performing complex cognitive tasks. For example, information-theoretic regularizers may help an agent learn robust state abstractions that enhance learning speed74,75,76 and form a simple but informative world model77,78. Our study demonstrates that in a simple cognitive task, both mechanisms serve the unified objective of minimizing representation complexity, guided by an information-theoretic regularizer. This finding facilitates communication between the two fields and contributes to a unified research framework for understanding both machine and human intelligence. Building on this line of thought, we plan to extend the current framework in future research to more complex task settings, such as multi-step Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), and explore whether complex human behaviors like planning and multi-task learning align with the predictions of information-theoretic regularizers within machine learning.

Recent research has suggested that human intelligence is more accurately described by the principle of resource-rationality79,80 than by the classical notion of rationality81. The resource-rationality principle emphasizes the need to consider computational costs in the pursuit of maximum reward, building on the classical notion of rationality. The combination of efficient coding and reward maximization principles applied in this study encapsulates the idea of resource-rationality, with reward maximization representing the notion of rationality and representation complexity representing computational costs. The basic idea is that information transmission in the brain incurs significant metabolic costs, thus minimizing representation complexity (a quantification of average information transmitted into the brain) serves as a reasonable proxy to minimize computational costs82. Notably, while numerous studies have employed resource-rationality to explain deviations from pure rationality in human behavior38,83,84, our research further emphasizes the advantages conferred by the principle, particularly in accounting for state abstraction, rewarding feature extraction, and generalization.

Methods

Ethics statement

Participants gave informed consent. The experimental protocol was approved by the University Committee on Activities involving Human Subjects at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (IRB-2055). Our experiment did not collect any demographical information from participants, including gender.

Materials

The experiments were designed based on the paradigm of acquired equivalence (AE)2,43,44. The experiment included two types of pictures: alien and scene. For the alien pictures, we utilized the “greebles” stimuli reported by Gauthier and Tarr85,86 (http://www.tarrlab.org/). The original greeble stimuli are purple. We created several new variants by modifying their color. Regarding the scene pictures, we sampled from the “Places205” picture database, as reported in Zhou et al.87 (http://places.csail.mit.edu/downloadData.html).

In the main experiment blocks, aliens and scenes were organized into sets. Each set comprised four alien stimuli (\(x\), \(x^{\prime}\), \(y\), \(y^{\prime}\)) and four scenes (\({a}_{1}\), \({a}_{2}\), \({a}_{3}\), \({a}_{4}\)), resulting in eight unique associations per set. Six of these associations were trained during the association stage, while all eight were tested in the testing stage. It is important to note that the stimuli in the AE task are defined to be “superficially dissimilar”. In our experiment, the greeble stimuli within a block were required to have the same color but exhibit mutually different shapes and appendages. There was no correlation between the alien’s shape (the configuration of its appendages) and the correct response.

Experiments

Experiment 1

We recruited 302 participants from Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk)88. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. All participants gave informed consent before starting the experiment. Each participant completed two practice blocks. To ensure a comprehensive understanding of the experiment, participants were required to achieve at least 70% accuracy in the second practice block to progress to the main experimental stage. Those who did not meet this criterion were allowed to repeat the second practice block until they achieved the necessary performance level; otherwise, they could not proceed to the main experiment. Participants received a base payment of $2 plus a bonus of up to $3 based on their response accuracy in this 20-minute experiment.

This project aimed to study generalization within the learning process, meaning participants who did not learn were outside the scope of this study. Consequently, we excluded 137 participants who failed a screening criterion (average accuracy lower than 60% for the last 24 trials, equating to 4 repetitions, in the training stage). All analyzes in Experiment 1 were conducted with the remaining 165 qualified participants.

The experiment consisted of two types of trials: training and testing. Each training trial comprised three screens. Following a 500 ms fixation screen, the trial presented an alien stimulus in the upper middle of the screen, along with photographs of scenes, offering one correct and one incorrect choice. Participants were instructed, “Which scene is associated with this alien?” and asked to respond by pressing the “F” or “J” key. These choices’ left-right order was counterbalanced across trials. The stimulus screen remained visible for ten seconds, followed by a one-second feedback screen displaying either “Correct! You got 1 point.” or “Incorrect! You got 0 point”. The test stage trials were identical, except that no feedback was provided after responses. In the testing stage, the experiment was directed to the next fixation screen following the participant’s response or after a maximum duration of ten seconds.

Experiment 1 included two experimental blocks. Each block consisted of a training stage, during which participants learned the stimulus-action associations, and a testing stage, during which participants were tested on the learned associations as well as an untrained generalization probe (the dashed associations). The training stage involved each association being trained ten times with feedback, resulting in 6 (associations) × 10 (repetitions) = 60 training trials. The testing stage tested both the trained and untrained associations six times, resulting in 8 (associations) × 6 (repetitions) = 48 testing trials. Participants were explicitly informed of the transition between the two experimental stages, and they were also reminded to keep and reapply their training experiences to achieve better performance.

Before the main blocks, each participant was required to complete two practice blocks. The first practice block contained a simple trial-and-error learning task, where participants were trained to learn the correct answer through feedback. They were asked to correctly associate \(x-{a}_{1}\) and \(y-{a}_{2}\) without being asked to build any between-stimuli equivalence. This block provided a gentle introduction to the experiment, with ten trials and unlimited response time. The primary goal of the first practice was to familiarize participants with the trial-and-error training process. The second practice served as a quiz. This block included a simplified version of the main training stage, where participants were presented with four stimuli but only required to choose from two actions. It contained 4 (associations) × 10 (repetitions) = 40 training trials. Participants needed to achieve 70% accuracy to pass the quiz; otherwise, they were required to repeat the second practice block before progressing to the main experimental blocks. The practice blocks were designed to help participants learn to establish between-stimuli equivalence in preparation for the main experimental blocks and used similar materials as the main blocks.

Experiment 2

We recruited 497 participants from MTurk. No statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. All participants gave informed consent prior to the experiment. Each participant completed two practice blocks. To ensure full understanding of the experiment, they needed to achieve at least 70% accuracy in the second practice block to proceed to the main experimental stage. Those who did not meet this criterion were given the opportunity to repeat the second practice block until they reached the required accuracy. All participants received a $3 base payment plus up to a $4.5 bonus based on their response accuracy in this 30-minute experiment.

We filtered the participants’ data using the same screening criterion as in Experiment 1. A total of 184 participants were excluded because they did not achieve an average accuracy of 60% for the last 24 trials (equivalent to 4 repetitions) in the training stage. All analyzes in Experiment 2 were conducted with the remaining 313 qualified participants.

Note that Experiment 2 included twice as many qualified participants as Experiment 1. This is because each participant in Experiment 1 completed two identical experimental blocks, while in Experiment 2, participants completed three different blocks, each corresponding to a different experimental condition. To ensure that each condition in Experiment 2 had a comparable amount of data to Experiment 1, we increased participant enrollment.

After completing the same practice blocks as in Experiment 1, participants were required to complete three main experimental blocks: a consistent block, a control block, and a conflict block. The sequence of these blocks was counterbalanced among participants. The three blocks were almost identical; the only difference lay in the stimuli’s appearance.

Within each block, participants were required to complete a 60-trial training stage, which was the same as in Experiment 1. They then entered the testing stage, where they had to respond to eight regular testing associations plus an additional probe stimulus. Consequently, the testing stage comprised 9 (associations) × 6 (repetitions) = 54 trials.

The remaining details of Experiment 2 were identical to Experiment 1. Note that, unlike the untrained associations, we did not predefine a correct answer for the probe stimulus. We simply record participants’ responses and hope to uncover which feature people were attending to by analyzing the response distribution.

Models

To set the stage, we first formalize a dynamic decision process in the AE paradigm. For consistency, we adopt a notation system similar to that used in the experimental paradigm.

We refer to a participant or decision maker as an agent. In each trial \(t\), an agent is presented with an alien stimulus \({s}_{t}\) from the set \(\{x,\,{x}^{{\prime} },{y},{y}^{\prime} \}\). The agent’s task is to select an action, specifically a scene picture \({a}_{t}\), from the set \(\{{a}_{1},\,{a}_{2},\,{a}_{3},\,{a}_{4}\}\), with the objective of maximizing the reward \(r({s}_{t},{a}_{t})\) based on the feedback received. The subscript \(t\) denotes the variable at a particular trial. Both the stimulus \(S\) and action \(A\) are defined as categorical variables.

RLPG: reinforcement learning policy gradient

RLPG is a computational level model. The goal of the RLPG model is to identify a policy \(\pi\) that optimizes the classical RL goal.

$${{\max }_{\pi }}{{E}_\pi} \left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)\right]$$

(4)

In the AE experiment, an agent was required to choose from two possible actions; before receiving any feedback, each action had a 50% chance of being correct. The agent should have had a baseline estimation of reward, denoted as \(b\), prior to making a decision. An action is considered positive when it yields a reward higher than the baseline and negative when the reward is lower. We revised Eq. 4 to include this baseline reward estimation \(b\),

$${{\max }_{\pi }} \, {{E}_{\pi }}\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]$$

(5)

The formula indicates that the RL baseline learns to adjust the policy π(a|s) to maximize received reward subtracted by the baseline r(st,at)-b. The reward subtracted by the baseline is commonly called advantage in the machine learning community. In this AE task, we assumed \(b\) = 0.5, corresponding to an expected reward of 0.5 (reward of 1 with 50% probability).

The objective function can theoretically be tackled by any RL algorithm, but we have chosen a particular approach for its simplicity: the policy gradient method. We assume the policy follows a parameterized softmax distribution, transforming the optimization problem into a parameter search:

$$\pi \left(a | {s;}\phi \right)=\frac{\exp \left[\phi \left(s,a\right)\right]}{{\sum }_{{a}^{{\prime} }}\exp \left[\phi \left(s,{a}^{{\prime} }\right)\right]}$$

(6)

where \(\phi\) denotes the parameters of the policy. Here, \(\phi\) is a 4-by-4 table (4 stimuli by 4 action). See Supplementary Note 2.1 for a graphical illustration of the model architecture. For simplicity, we will denote this softmax formula as \({{{\rm{softmax}}}}(\phi (s,a)).\)

Let \(J\left(\phi \right)={\max }_{\phi }E\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]\), then the policy parameters were updated based on the gradient of the objective function \({\nabla }_{\phi }J(\phi )\),

$$\phi \left(s,a\right)=\phi \left(s,a\right)+{\alpha }_{\pi }{\nabla }_{\phi } \, J\left(\phi \right)\left(s,a\right)$$

(7)

where \({\alpha }_{\pi }\ge 0\) is the learning rate of policy \(\pi\). This policy learning rate is the only parameter in the RL baseline model. The policy parameters \(\phi\) were initialized to 0 before the experiment. Equation 7 updates the policy via its gradient, which gives the name “policy gradient”. We have derived the analytical gradient for both models and verified the derivation using pyTorch package89. See supplementary material for detailed derivation. The RLPG model features a single parameter: the policy’s learning rate, \({\alpha }_{\pi }\).

There are two remarks related to this simple model. First, though not explicitly shown, the RLPG assumes a perfect representation that fully reconstructs the stimulus. If we construct a model that explicitly includes the representation \(z\) and assume that each stimulus \(s\) deterministically maps to a unique representation \(z\), the model nevertheless collapses to the RLPG model described above. Second, the RLPG model introduced in this study behaves similarly to the classic Q-learning model which is extensively used in psychology25. The most significant advantage of RLPG is its simplicity. The model has a single learning rate parameter, simultaneously approximating the effects of both the “learning rate” and “inverse temperature” parameters in the classic model. This allows for a more effective distillation of the computational essence underlying representation compression.

ECPG: efficient coding policy gradient

The ECPG model is designed with a dual computational goal: to maximize reward while minimizing representation complexity.

$${{\max }_{\psi,\rho }} \, {E}_{\psi,\rho }\left[r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right]-\lambda {I}^{\psi }\left({S;Z}\right)$$

(8)

The parameter \(\lambda \ge 0\), referred to as the simplicity parameter, controls for the tradeoff between the classical RL objective and representation simplicity. When \(\lambda=0\), the agent does not compress stimuli representations for simplicity, focusing solely on reward maximization. Conversely, as \(\lambda \to \infty\), the agent learns the simplest set of representations, encoding all stimuli into a single, identical representation. Therefore, an optimal \(\lambda\) balances compression and oversimplification.

The introduction of latent representation \(z\) divides the policy into an encoder, \(\psi\), and a decoder, \(\rho\), both of which are optimized according to Eq. 8. Like the RLPG, we solve Eq. 8 using the policy gradient. Here, we considered a parameterized softmax encoder \(\psi ({z|s;}\theta )\) and a decoder ρ(a│z;ϕ). The encoder parameter θ is a 4-by-4 table (4 stimuli by 4 representations) and the decoder parameter \(\phi\) is also a 4-by-4 table (See Supplementary Note 2.3.3 for a graphical illustration of the model architecture). The policy \(\pi\) is derived from the combination of the encoder and decoder:

$$\pi \left({a}_{t} | {s}_{t}\right)={\sum }_{z}\phi \left(z | {s}_{t};\theta \right)\rho \left({a}_{t} | {z;}\phi \right)$$

(9)

We iteratively update the encoder and decoder to optimize Eq. 8 using the following scheme:

$$\left\{\begin{array}{c}{\max }_{\theta }J\left(\theta \right)={\max }_{\theta } {\sum} _{z}\psi \left(z | {s}_{t};\theta \right)\left[\rho \left({a}_{t} | z\right)\left(r\left({s}_{t} ; {a}_{t}\right)-b\right)-\lambda \log \frac{\psi \left(z | {s}_{t};\theta \right)}{p\left(z\right)}\,\right]\\ {\max }_{\phi }J\left(\phi \right)={\max }_{\phi }{\sum} _{z}\rho \left({a}_{t} | {z;}\phi \right)\left[\psi \left(z | {s}_{t}\right)\left(r\left({s}_{t},{a}_{t}\right)-b\right)\right] \hfill \\ p\left(z\right)={\sum} _{s}\psi \left(z | s\right)p\left(s\right) \hfill \end{array}\right.$$

(10)

Here, \(p(z)\) indicates the prior preference to the representation \(z\). The first two optimization problems were solved using gradient ascent with learning rate parameters, \({\alpha }_{\psi }\) and \({\alpha }_{\rho }\). The prior representation probability \(p(z)\) was updated according to the definition of marginal probability. In practice, we also experimented with updating the prior in the gradient formula but found it made no significant difference in modeling human behavior. Therefore, we adopted the current scheme to reduce the number of free parameters.

The initialization of the representation variable \(z\) is critical. In this article, \(z\) is a categorical variable that shares the same sample space as the stimulus. The encoder parameters \(\theta\) are initialized by passing the product of an identity matrix and an initial value through a softmax function,

$$\psi \left(z | {s;}{\theta }_{0}\right)={{{\rm{softmax}}}}\left({\theta }_{0}{{{\bf{I}}}}\left(s,z\right)\right)$$

(11)

where I is an identity indicator \({{{\bf{I}}}}\left(s,z\right)=1\,{{{\rm{if\,}}}}{z}=s\) \({{{\rm{otherwise}}}}\,0\). We pretrained the encoders to reach 99% discrimination accuracy by tuning the initial value \({\theta }_{0}\). The initial encoder in this case encoded stimuli almost orthogonally, reflecting the “superficially dissimilarity” in the definition of AE. See “Method-Pretrain an encoder” for more details.

In summary, the ECPG model has three parameters: an encoder learning rate \({\alpha }_{\psi }\), a decoder learning rate \({\alpha }_{\rho }\), a simplicity parameter \(\lambda\). The stimulus encoder parameters were initialized through pretraining, and the parameters of the decoder were initialized to 0.

The ECPG model’s encoder acts as a generative component, similar to the encoder in the beta variational autoencoder (\(\beta\)VAE) as described by Higgins et al.13 but with a categorical hidden layer instead of a continuous Gaussian distribution. This design facilitates the computation of mutual information and the quantification of representation complexity, building upon the work of Lu et al.90.

CPG: the intermediary model

The cascade policy gradient (CPG) model is a special case of the ECPG model, with the simplicity fixed at 0, \(\lambda=0\). Therefore, the model has only two parameters: the learning rate for the encoder \({\alpha }_{\psi }\) and the learning rate for the decoder \({\alpha }_{\rho }\).

fRLPG: the feature-based RLPG model

The feature-based models we developed are extensions of the models previously introduced. The primary difference lies in the incorporation of a feature embedding function \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) that maps a stimulus \(s\) onto a set of features \(f\). We crafted a feature embedding function to decompose a greeble stimulus into three distinct features: shape, color, and appendage, using “one-hot encoding” for clear differentiation. For instance, the color “purple” is represented as [1, 0, 0, 0, 0] and “yellow” as [0, 1, 0, 0, 0]. The feature function \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) each input stimulus with its one-hot code and concatenates these codes into a 15-dimensional vector \(f\), which serves as the model’s input (See Supplementary Fig. S7C).

We modified the policy of the fRLPG model to create a feature-based baseline RL model that does not compress stimuli. This model proposes that visual similarity alone could account for human generalization performance, without the need for a representation compression mechanism. With the feature embedding function \({{{\mathcal{F}}}}\) defined, the policy at trial \(t\) can be expressed as follows,

$$\pi \left(a | {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left({s}_{t}\right);\phi \right)={{{\rm{softmax}}}}\left(\phi \left({f}_{t},a\right)\right)$$

(12)

The parameter \(\phi\) now is a 15-by-4 table. As before, the parameter \(\phi\) was updated using the policy gradient method Eq. 7, and actions are selected by sampling from the softmax policy, Eq. 12. The model has one parameter, the learning rate of policy \({\alpha }_{\pi }\).

fECPG: the feature-based ECPG model

We modified the ECPG encoder to include the feature embedding function and preserved the previous ECPG decoder formulation (See Supplementary Fig. S7D),

$$\psi \left(z | {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left({s}_{t}\right);\theta \right)={{{\rm{softmax}}}}\left(\theta \left({f}_{t},z\right)\right)$$

(13)

The parameter \(\theta\) now is a 15-by-4 table. The decoder \(\rho ({a|z;}\phi )\) remains unchanged.

A new challenge we faced was initializing the encoder parameters for the feature-based model. The previous method, which relied on an identity matrix, was no longer suitable because stimuli with overlapping features naturally appear more similar. For instance, a purple greeble should be more similar to another purple greeble than to a yellow one.

To address this, we introduced a new initialization technique:

First, we measured the visual similarity between a stimulus \(s\) and all possible stimuli \(z\) (including stimuli \(s\) itself) by calculating the dot product of their feature embeddings,

$${{{\rm{sim}}}}\left({{s}},{{z}}\right)=\left\langle {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left(s\right),{{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left(z\right)\right\rangle \,\forall z\in \left\{x,{x}^{{\prime} },y,{y}^{{\prime} }\right\}$$

(14)

Second, we multiplied these similarity scores by a scalar \({\theta }_{0}\) and passed them through a softmax function to form the representation of stimuli \(s\),

$$\bar{\psi }\left(z | s\right)={{{\rm{softmax}}}}\left({\theta }_{0}{{{\rm{sim}}}}\left(s,z\right)\right)$$

(15)

As before, the initial value \({\theta }_{0}\) is tuned through pretraining. This value controls the perceived similarity between stimuli. When \({\theta }_{0}\) is small, stimuli with overlapping features look similar.

Finally, we used the representation \(\bar{\psi }\left(z,|,s\right)\) as supervised labels to train the model encoder \(\psi \left(z{{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left(s\right),\,\theta \right)\) by minimizing their cross-entropy loss

$${\min }_{\theta }-{\sum}_{z}\bar{\psi }\left(z | s\right)\log \psi \left(z | {{{\mathcal{F}}}}\left(s\right),\theta \right)$$

(16)

Once the training has converged, the encoder for the fECPG model is considered initialized. The subsequent learning and decision-making processes are consistent with the original ECPG model.