- COMMENT

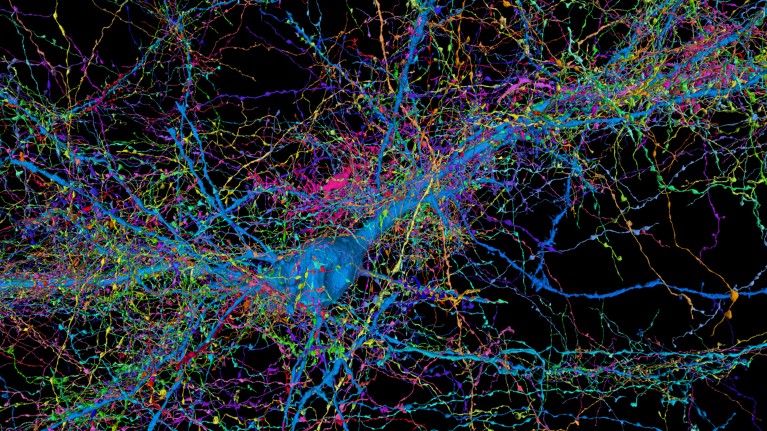

Early machine-learning systems were inspired by neural networks — now AI might allow neuroscientists to get to grips with the brain’s unique complexities.

By

-

Viren Jain

-

Viren Jain is a senior staff research scientist at Google Research, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California, and leads the Connectomics at Google team.

-

A reconstruction of incoming connections to a single human neuron, called a pyramidal cell. Credit: A. Shapson-Coe, M. Januszewski, D. Berger, A. Pope, V. Jain & J. Lichtman

Can a computer be programmed to simulate a brain? It’s a question mathematicians, theoreticians and experimentalists have long been asking — whether spurred by a desire to create artificial intelligence (AI) or by the idea that a complex system such as the brain can be understood only when mathematics or a computer can reproduce its behaviour. To try to answer it, investigators have been developing simplified models of brain neural networks since the 1940s1. In fact, today’s explosion in machine learning can be traced back to early work inspired by biological systems.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

from$1.95

to$39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 623, 247-250 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03426-3

References

McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115–133 (1943).

Jefferis, G., Collinson, L., Bosch, C., Costa, M. & Schlegel, P. Scaling up Connectomics (Wellcome, 2023).

Cook, S. J. et al. Nature 571, 63–71 (2019).

Winding, M. et al. Science 379, eadd9330 (2023).

Dorkenwald, S. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.27.546656 (2023).

De Ceglia, R. et al. Nature 622, 120–129 (2023).

Schretter, C. E. et al. eLife 9, e58942 (2020).

Wilson, R. I. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 46, 403–423 (2023).

Wanner, A. A. & Friedrich, R. W. Nature Neurosci. 23, 433–442 (2020).

Vishwanathan, A. et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.28.359620 (2020).

Petrucco, L. et al. Nature Neurosci. 26, 765–773 (2023).

Chen, X. et al. Neuron 100, 876–890 (2018).

Takemura, S.-Y. et al. Nature 500, 175–181 (2013).

Kilman, V. L. & Marder, E. J. Comp. Neurol. 374, 362–375 (1996).

Bargmann, C. I. & Marder, E. Nature Methods 10, 483–490 (2013).

Lam, R. et al. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.12794 (2023).

Espeholt, L. et al. Nature Commun. 13, 5145 (2022).

Witvliet, D. et al. Nature 596, 257–261 (2021).

Haspel, G. et al. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.06578 (2023).

Frégnac, Y. & Laurent, G. Nature 513, 27–29 (2014).

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Gigantic map of fly brain is a first for a complex animal

Gigantic map of fly brain is a first for a complex animal

This is the largest map of the human brain ever made

This is the largest map of the human brain ever made

How the world’s biggest brain maps could transform neuroscience

How the world’s biggest brain maps could transform neuroscience