What if there were a straightforward and relatively inexpensive way to lower the incidence of heart failure (HF), renal disease, stroke, and cognitive impairment? Cardiologist Bertram Pitt, MD, said there is: test for aldosterone.

“If we could get better at testing for aldosterone and treating people with high aldosterone-renin ratio or low renin levels, we would have a much lower incidence of these conditions,” Pitt told Medscape Medical News. “We’re talking about saving millions of people and many millions of dollars, yet we’re just not doing too much about it.”

Pitt, a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is a pioneer in aldosterone research. At 93, he remains actively involved in the field — and in getting the word out about the significance of this often-overlooked hormone.

“Despite all the evidence we have on aldosterone dysregulation in disease, very few clinicians are measuring aldosterone-renin ratios,” he said.

When Aldosterone Goes Awry

Aldosterone is a mineralocorticoid hormone produced in the adrenal glands and its secretion is stimulated by the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) pathway. After binding to mineralocorticoid receptors, primarily in the kidneys, it promotes reabsorption of urinary sodium, raising intravascular volume and blood pressure.

When in balance, the substance plays key roles in regulating blood pressure, electrolytes, and fluid homeostasis. However, excess aldosterone — or aldosteronism — is more common than previously believed.

Excess aldosterone expands plasma volume, leading to hypertension, even when the RAAS pathway is suppressed with antihypertensive drugs like angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Elevated aldosterone with suppressed plasma renin activity is the cause behind about 30% of cases of resistant hypertension. Primary aldosteronism is present in about 10% of people with hypertension, many of whom are asymptomatic.

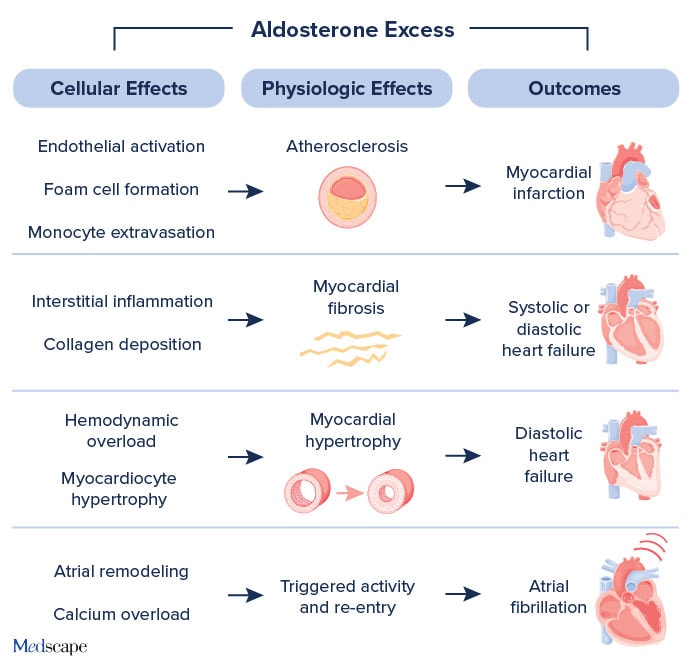

Beyond the RAAS pathway, chronic excess circulating aldosterone promotes inflammation and fibrosis of the heart, vasculature, and kidneys, leading to end-organ damage — often independent of its effects on blood pressure. The results: coronary artery disease, left ventricular hypertrophy, HF, and atrial fibrillation (Figure 1).

Testing Is Underutilized

A new 2025 guideline from the Endocrine Society recommends measuring serum aldosterone and the aldosterone-renin ratio in all patients with newly diagnosed hypertension to detect primary aldosteronism. Aldosteronism is defined as serum aldosterone > 20 ng/dL or an aldosterone-renin ratio ≥ 20:1.

According to Pitt, aldosterone levels should also be checked in any patient with:

- uncontrolled hypertension;

- significant variability in blood pressure, which is a sign of increased aldosterone activation;

- nondipping nocturnal hypertension;

- salt-sensitive hypertension; or

- concomitant hypertension and obesity because this accounts for 65%-78% of primary hypertension cases.

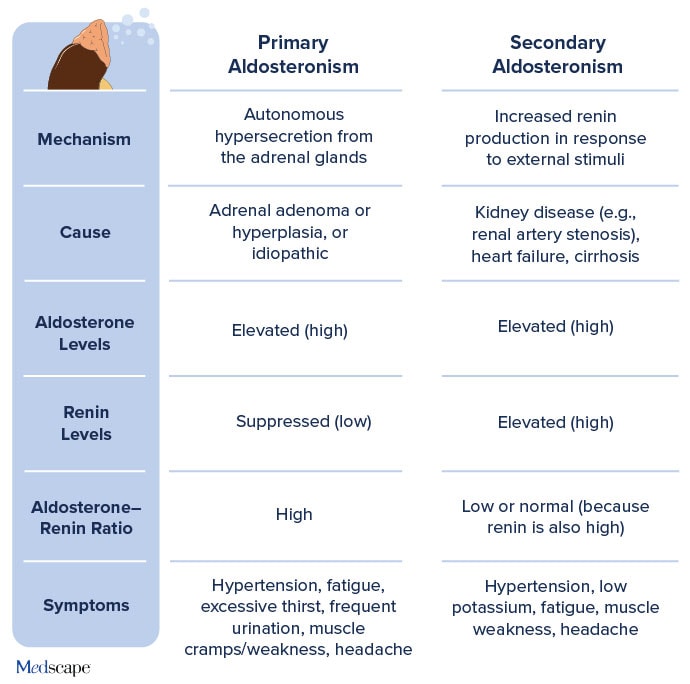

Clinicians should be aware of primary and secondary causes of aldosteronism, Pitt said. While aldosterone levels are high in both types, renin levels and the aldosterone-renin ratio differ between the two forms of the condition (Figure 2).

Some categories of patients warrant a closer look when interpreting aldosterone levels, Pitt said. In older people, for example, aldosterone levels may be normal or even decreased because of age-related declines in renin-angiotensin activity, while upregulation of mineralocorticoid receptors in vascular smooth muscle can increase receptor activity. This heightened activity can cause vascular inflammation despite normal aldosterone levels, he said.

What About Treatment?

“If a patient has excess aldosterone, it will be easier to control their hypertension by specifically targeting that mechanism,” Pitt said. That means using aldosterone receptor antagonists — now called mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs). The category includes the steroidal formulas spironolactone and eplerenone, and one nonsteroidal, finerenone.

Pitt was the lead investigator in the landmark RALES trial, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 1999, which enrolled 1663 patients with severe HF who were already on an ACE inhibitor, loop diuretic, and, in most cases, digoxin. Adding spironolactone to the regimen reduced the risk for death from any cause by 30%, a finding primarily driven by lower risks for dying from progressive HF or sudden death from cardiac causes.

A later study of the second-generation MRA eplerenone showed improved outcomes for patients with left ventricular dysfunction following a myocardial infarction. Dose-for-dose, eplerenone is less potent than spironolactone for lowering blood pressure, but the dose can be adjusted to achieve similar effects. Finerenone is also an option, although less affordable, Pitt noted.

Downsides of MRAs

While the data are strong for treating hypertension and reducing both HF and cardiovascular mortality, MRAs are not as widely prescribed as other drugs that act along the RAAS pathway, namely ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers.

Wider use of MRAs could make a big difference in cardiovascular outcomes, said Gregg Fonarow, MD, director of the Ahmanson-UCLA Cardiomyopathy Center and co-director of UCLA’s Preventative Cardiology Program. Over the years, Fonarow has advocated for increased use of MRAs for conditions like atrial fibrillation and heart failure.

“There’s a disconnect between the proven benefits of MRAs in randomized clinical trials, class I guideline recommendations, and their real-world use in clinical practice,” which is especially true for patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and post-myocardial infarction left ventricular dysfunction, Fonarow told Medscape Medical News.

The gap can be attributed to several factors, he said. “Many clinicians underestimate the role of aldosterone in myocardial fibrosis, vascular inflammation, and arrhythmogenesis. The RAAS system tends to be viewed through the lens of ACE inhibitors and ARBs [angiotensin receptor blockers], so MRAs are seen as adjunctive rather than foundational therapies.”

The combination of steroidal side effects like gynecomastia, fear of hyperkalemia, and the need for regular monitoring of serum potassium and renal function often relegate MRAs to the “maybe later” pile. These factors limit the use of MRAs, particularly in older adults and people with renal impairment, according to Fonarow.

“The need for potassium and renal function monitoring may deter use in busy outpatient settings or among clinicians who are unfamiliar with their nuances,” he said.

Fonarow also urges clinicians to consider other strategies for reducing the risk for hyperkalemia associated with MRAs. For instance, in some cases, a diuretic, an SGLT2 inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor can be used in place of an ACE inhibitor or ARB in patients with HF and chronic kidney disease.

MRAs are underused despite clear guideline recommendations in certain patient groups, such as those with HFrEF or post-myocardial infarction left ventricular dysfunction, noted Fonarow, who is a co-author of the CHAMP-HF study and the American Heart Association’s Get with the Guidelines papers in HF and atrial fibrillation. “Even with clear indications, clinicians often default to beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors or ARBs, overlooking MRAs along with other guideline-directed therapies unless they’re prompted by severe symptoms or hospitalization,” he said.

Fonarow is also a senior author for studies evaluating quality improvement initiatives, such as IMPROVE-HF and the more recent IMPLEMENT-HF. “These studies have demonstrated that safe use of MRAs can be improved,” he said. “Our 2024 study achieved utilization rates of 80% or more among eligible patients with HFrEF.”

Enter Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitors

If lowering aldosterone levels is the goal, would it work better to block production of aldosterone itself? An investigational category of drugs, aldosterone synthase inhibitors, blocks this enzyme in the adrenal glands to stop aldosterone production at the source. Unlike MRAs, which block receptor binding, aldosterone synthase inhibitors reduce circulating aldosterone, mitigating some of the off-target effects.

In resistant hypertension, especially cases caused by primary aldosteronism, studies suggest that aldosterone synthase inhibitors like baxdrostat, lorundrostat, and dexfadrostat may provide superior blood pressure control without the side effects of MRAs. For example, a baxdrostat study published in October 2025 showed improved control of resistant and uncontrolled hypertension in patients already taking two or three other antihypertensives, including a diuretic.

In HF, aldosterone synthase inhibitors could complement or replace MRAs, especially in patients who are intolerant to spironolactone or eplerenone, Fonarow suggested. They may also have a role in cardiorenal syndromes. “By reducing aldosterone-driven fibrosis and sodium retention, aldosterone synthase inhibitors may benefit patients with comorbid renal and cardiac dysfunction,” he said.

“Aldosterone synthase inhibitors are better tolerated and much more specific [than MRAs], so in that sense they’re a great advance,” Pitt agreed. “But I don’t think we should be jumping up and down without further proof.”

Direct comparative studies between MRAs and aldosterone synthase inhibitors are lacking, he pointed out. “And while lowering blood pressure is important, what is more important is outcomes: preventing HF, renal disease, stroke, and cognitive impairment. We don’t have the data for these outcomes with aldosterone synthase inhibitors yet, and we don’t have any comparative data between MRAs and aldosterone synthase inhibitors.”

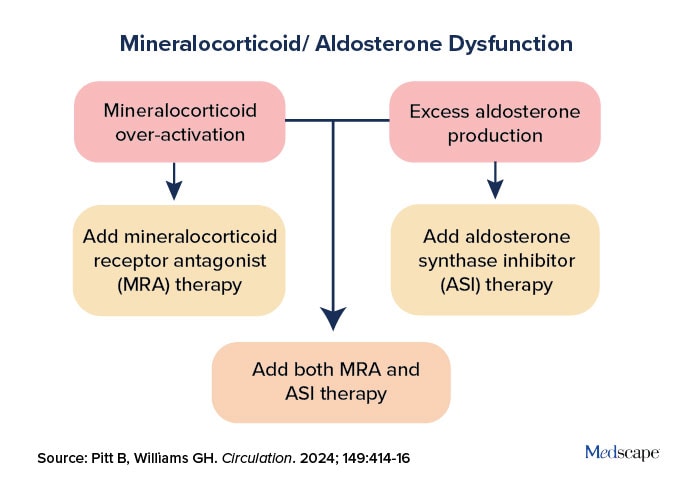

Ideally, both MRAs and aldosterone synthase inhibitors could be employed in a targeted manner to treat mineralocorticoid/aldosterone dysfunction (Figure 3). In a recent paper in Circulation comparing the two, Pitt concluded, “When the dust settles, it is likely that the outcome will be more collaborative than competitive.”

Both Pitt and Fonarow stress that more attention to aldosterone is warranted. Hypertension is the second-leading cause of HF, Pitt observed in a 2024 “call to action” paper. The bottom line in his call to action? “Broader consideration of aldosterone excess and earlier aldosterone-directed treatment can help substantially reduce the burden of HF caused by hypertension.”

Fonarow reported consulting for Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cytokinetics, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer. Pitt reported consulting for or stock holdings with Anacardia, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cereno Scientific, Corteria, G-3 Pharmaceuticals, KBP Biosciences, Lexicon, Proton Intel, Sarfez, SC Pharmaceuticals, SQ Innovation, and Sea Star Medical. He is on the data monitoring and safety board of Mineralys Therapeutics and has US patents related to aldosterone and histone modulating agents.