Iain Morris, International Editor, Light Reading

August 22, 2025

7 Min Read

![]()

(Source: Pitinan Piyavatin/Alamy Stock Photo)

Offloading cognitive effort to ChatGPT or a similar application is extremely bad for the brain. Who knew? It should have been obvious to anyone who's realized that lounging around all day is bad for the body, or that no one became good at anything by not doing it. But it took two separate research projects, one by Microsoft and Carnegie Mellon University and the other by MIT, to establish that overreliance on generative artificial intelligence (GenAI), as the madmen of Big Tech call it, turns you into a technologically lobotomized ape.

It now appears to be even more damaging than all that, according to Mustafa Suleyman, the head of AI for Microsoft and the author of the portentously titled The Coming Wave (spoiler alert, AI is going to be seriously disruptive, writes man who stands to earn millions from serious AI disruption). If you've not heard of what Suleyman and others are describing as "AI psychosis," it is a new ailment whose sufferers are convinced AI is sentient. In a case of life imitating art, some people have apparently grown emotionally attached to the machine voices emanating from their phones and even, like Joaquin Phoenix in the movie Her, fallen in love with their chatbots.

AI psychosis is feasibly a natural consequence of the cognitive decline researchers observed in heavy users of ChatGPT, much as the onset of lung cancer is for the coughing yet dedicated smoker. In defense of the afflicted, it has been encouraged by two years of insane industry babble about what is basically just a very sophisticated search engine, the progeny of the pattern recognition system that Google's founders worked on in the late nineties.

Scaremongering headlines about job losses and murderous robots have probably contributed to AI psychosis. Hardly any commentator has even objected to the marketing of the technology under the AI banner. Yet backers have had to invent the new label of artificial general intelligence (AGI) to describe what AI was supposed to be until ChatGPT came along.

Meanwhile, the world mercifully looks no closer to AGI. It is impossible to see how a superior intelligence that outperforms the smartest humans on all fronts could be a positive for the planet's dominant species, but that hasn't stopped Sam Altman and other latter-day Frankensteins from trying to create one. The highly anticipated GPT-5 has fallen scandalously short of expectations and is merely an incremental improvement on GPT-4 rather than some AGI-like breakthrough. Building even bigger large language models (LLMs) and more powerful graphical processing units (GPUs) hasn't been fruitful and probably never will be thanks to the law of diminishing returns.

GPT-5 also looks as rubbish as its predecessors. Richard Windsor of Radio Free Mobile set it two illustrative tasks – first, "draw a picture of a person writing with their left hand," and second, "draw a picture of a person holding a sign saying AGI is imminent. Circle all of the vowels." The resulting images, shown in his blog, feature a right-handed scribe and a man holding an "AGI is imminent" sign with two circled consonants. It offers proof, writes Windsor, that the generative AI tool "still demonstrates no understanding of causality."

What AI-related job cuts?

But in the absence of any other game changer for their business, telcos still sound captivated by AI, shoehorning it into any gaps they can find. No announcement seems complete without a reference to the technology and its supposed benefits, which remain largely invisible to outsiders. It has neither spurred revenue growth nor boosted profitability, and it has certainly not given telcos an array of new services to sell.

AI has had an impact on networks mainly by generating additional traffic in and between the data centers training LLMs, which looks good for vendors of data center connectivity products like Arista, Ciena, Cisco, DriveNets, Juniper (now owned by HPE) and Nokia. Radio access network (RAN) vendors like Ericsson pray to Loki or some other mischief-making deity that it will eventually have the same impact on 5G traffic, as well. Few are convinced, and the effect of that would be to squeeze telco margins, forcing operators to spend more on 5G infrastructure when there is no obvious prospect of higher sales.

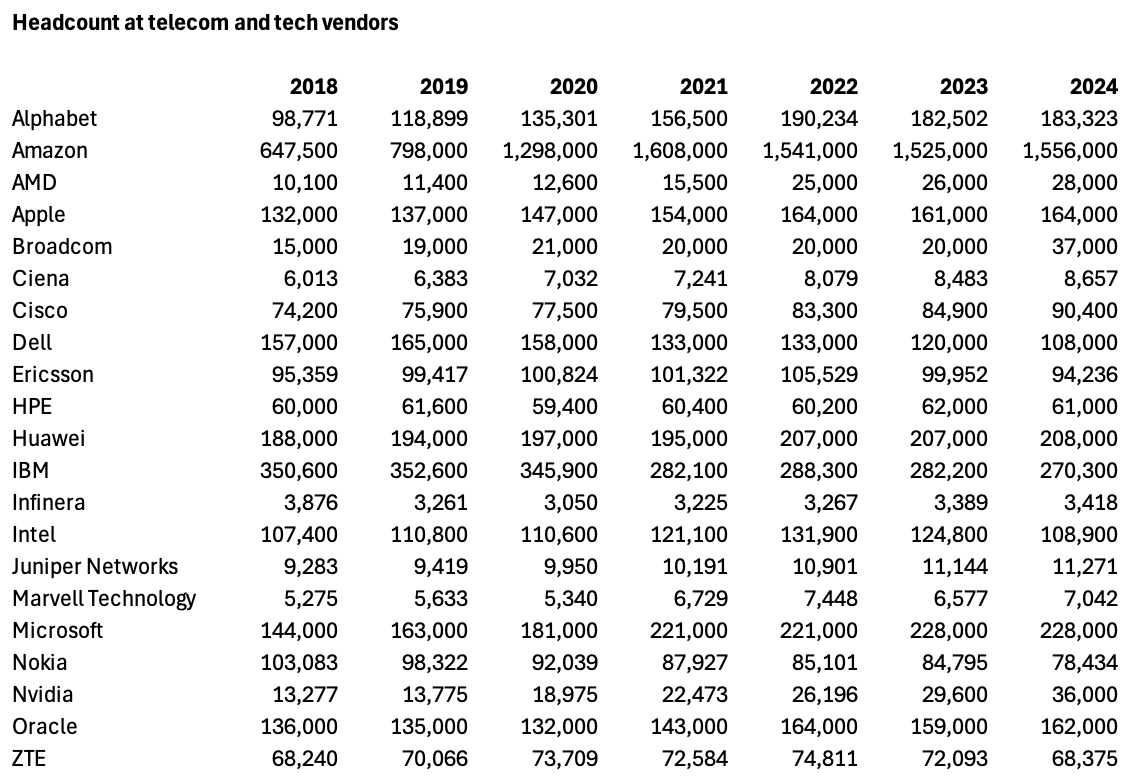

Every week seems to bring another news story about telecom and tech-sector layoffs linked to AI. Yet most are extremely misleading. Even the tech giants perceived to be emptying their buildings of staff and installing AI everywhere employ far more people than they did just a few years ago. Microsoft's workforce grew from 144,000 people in 2018 to 228,000 last year. Alphabet, Google's parent, finished 2024 with 183,323 employees, up from 98,771 six years ago. Amazon's workforce has grown 2.4 times over this period, to an astonishing 1.556 million people – making it bigger than the population of Estonia, although not South Korea, as Google's Gemini chatbot wrongly deduced when tested by Light Reading (see below).

The job cuts that have happened in the community of telecom and tech vendors have so far had little if anything to do with AI. Instead, they have either been concentrated in a few sub-sectors that have suffered a downturn (like 5G) or struck companies in crisis. The workforce at Nokia, which has lost market share in a shrinking 5G sector, withered by almost 25,000 employees between 2018 and 2024, for instance.

Meanwhile, ailing chipmaker Intel cut 23,000 jobs between 2022 and 2024, about 17% of the total, and aims to finish this year with 75,000 employees, implying another 34,000 will vanish in 2025. IBM's shrinkage was a result of spinning off Kyndryl, its managed services business. Excluding Amazon, with its giant workforce, the companies examined by Light Reading collectively gained almost 179,000 employees between 2018 and 2024. Chip designers AMD and Nvidia have nearly trebled in size.

(Source: annual reports, SEC filings)

Fewer diggers required

This is a markedly different story from the one Light Reading has documented in the telco world for years. The 20 Tier 1 operators this publication regularly tracks have slashed combined headcount by more than 348,000 jobs since 2018, about 20% of that year's total. They show no sign of stopping.

But most cuts are a result of divestiture, outsourcing, routine efficiency measures and earlier forms of automation unrelated to AI. In the UK, BT expects to cut up to 55,000 jobs by 2030 compared with 2023, about 42% of its workforce, not because of AI but as fewer people are needed for a nationwide fiber rollout that will be nearing completion. What's more, fewer industry jobs were cut in the two years after ChatGPT's launch than in the two years leading up to it. The reduction totals about 95,600 for 2023 and 2024, compared with more than 150,000 for 2021 and 2022.

Technology executives within telcos would undoubtedly reject the argument that AI is useless. The standard retort is that telcos would not be able to operate such complex networks with so many parameters if they did not have access to the latest AI tools. But many of these fault-finding, predictive maintenance and intent-based networking technologies existed long before ChatGPT surfaced. They have nothing in common with the popular conception of AI and properly fall under the umbrella of data analytics, or perhaps machine learning. Ever since the invention of the wheel, technology has helped people to reduce manual effort. That does not qualify it as artificially intelligent.

Telecom's love affair with AI probably won't end soon, but the shine seems to be wearing off the label. As reported by Telecoms.com, Light Reading's sister publication, tech stocks fell this week after the disappointment of the just-released GPT-5. And a new report from MIT included a troubling assessment for AI's salesmen. "Despite $30–40 billion in enterprise investment into GenAI, this report uncovers a surprising result in that 95% of organizations are getting zero return," reads the opening sentence of its executive summary. That doesn't sound very smart at all.

About the Author

International Editor, Light Reading

Iain Morris joined Light Reading as News Editor at the start of 2015 -- and we mean, right at the start. His friends and family were still singing Auld Lang Syne as Iain started sourcing New Year's Eve UK mobile network congestion statistics. Prior to boosting Light Reading's UK-based editorial team numbers (he is based in London, south of the river), Iain was a successful freelance writer and editor who had been covering the telecoms sector for the past 15 years. His work has appeared in publications including The Economist (classy!) and The Observer, besides a variety of trade and business journals. He was previously the lead telecoms analyst for the Economist Intelligence Unit, and before that worked as a features editor at Telecommunications magazine. Iain started out in telecoms as an editor at consulting and market-research company Analysys (now Analysys Mason).