It was a sunny mid-March morning in 2022 when Alek Schott headed home to Houston from Carrizo Springs, near the Mexico border. He had just finished a training for his pipeline supply company and dropped a carpool colleague off at the local Holiday Inn where she’d stayed the previous night. He turned on his dash camera and started driving.

About an hour into the trip, a Bexar County sheriff’s deputy parked on the east side of Interstate 35 flipped on his lights and followed Schott’s truck to the shoulder. He’d seen the pickup drift over the yellow line, he explained, a violation of state traffic laws.

Driver Alek Schott steps out of his car at the request of a Bexar County sheriff's deputy during a 2022 traffic stop.

Court recordsWhat Schott, who has no criminal history, couldn’t have known is that he had been tagged as a potential lawbreaker by a vast and mysterious surveillance system along the South Texas region’s roadways. A network of cameras scanning license plates of passing vehicles had crunched the data in real time and determined that the details of his trip — a quick excursion to the border with a woman dropped off at a hotel — suggested smuggling behavior.

Article continues below this ad

The information was relayed over an anonymous WhatsApp chat group to Bexar County deputies. Their role was to wait for Schott to drive by, then find a way to stop him and look inside his vehicle.

When Deputy Joel Babb asked if he could search the truck, Schott declined — his legal right. So Babb summoned a drug dog, which happened to be waiting nearby. The dog “alerted,” signaling he’d sniffed contraband, giving the police the legal right to search anyway.

Interdiction deputies were suspicious from the start.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Article continues below this ad

After more than an hour, nothing was found — although one deputy still reported seeing a “very, very, very, very little amount” of drugs in the truck.

Police promote interdiction — using traffic stops to investigate more serious crimes — as a way to interrupt criminal activity rather than simply respond to it. Over the past 100 years, Americans inconvenienced by searches have accepted the tactic as an acceptable cost of public safety.

Yet statistically interdiction teams have not been good at predicting who is committing a crime. Research has found most discretionary searches turn up nothing. Of those that do, the contraband found often is so inconsequential that charges are never filed.

A Houston Chronicle analysis of traffic stop data for Texas law enforcement agencies shows the Bexar County Sheriff's Office self-reported finding contraband in 70% of total searches — a rate much higher than that of nearly every other large police, sheriff's and constable's office in the state. Yet those "hits" also resulted in an arrest far less frequently than in those other jurisdictions.

Bexar County’s interdiction team also was so unsuccessful that Sheriff Javier Salazar joked about it. According to court documents, while the team made hundreds of stops, “I would rib them about not being very effective at drug interdiction, not finding drugs very often,” he recently testified.

Article continues below this ad

Relieved to be released with only a warning, drivers rarely complain. Schott, however, sued.

Bexar County did not respond to interview requests, but in the past has declined to discuss the case, citing the ongoing litigation. In court filings, its lawyers have defended Schott’s stop and search as legal and its deputies behavior as largely appropriate. Babb testified that he acted according to his training.

Videos from every party involved, as well as text and WhatsApp exchanges, emails and internal reports, have been entered into evidence in the case, which remains pending. Taken together, they provide a rare inside look that illustrates nearly everything critics say is wrong with the practice of stopping and searching motorists.

“Deputy Babb made up a violation,” Schott’s attorney, Christie Hebert, said at a hearing at the San Antonio federal courthouse last month. Then, “the deputy found nothing in Alek’s truck. That’s because they usually find nothing.”

Article continues below this ad

The intelligence

Schott was told he was stopped because he drifted outside his lane. But that was only the method police used to pull him over.

Deputies acknowledged they were looking for Schott's pickup before they stopped him.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Bexar County sheriff’s deputies acknowledged waiting for Schott’s black pickup to drive by after receiving an intelligence report via an anonymous WhatsApp chat that flagged his travel pattern as suspicious.

Deputy Joel Babb references a mysterious WhatsApp group.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Article continues below this ad

The thread was called the Northwest Highway Group, they testified. It provided real-time alerts to police departments farther away from the border.

The Bexar deputies couldn’t identify anyone in the group or where the information came from, other than they understood it was generated by a team working out of a dedicated intelligence facility.

The WhatsApp thread disseminated real-time intelligence about suspicious vehicles.

Court records

“Their job is to sit in fusion centers and actually watch travel patterns on the highway, being LPR (license plate reader) reads and whatever other cool stuff they have that I don't know what it is,” Babb said in a deposition.

Formed after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, fusion centers are federally recognized, state-run intelligence-gathering hubs where police from local, state and federal organizations team up to gather and distribute intelligence. Texas boasts eight of the secretive facilities, more than any other state. In court filings, Bexar County said the Schott intelligence came from “the Laredo Fusion Center” — a location not on any official list.

Members of the San Antonio Police Department describe their work at the Southwest Texas Fusion Center.

Promotional video, SAPD

Much fusion work involves merging and analyzing information gathered from various sources that collect information about civilians, according to Sarah Brayne, a Stanford University professor who has studied the centers. Many of their tools were developed for the military to conduct counter-terrorism work but have filtered down to law enforcement.

One common — and growing — set of surveillance data is from automatic license plate readers, which identify vehicles that drive past. Pairing the readings with artificial intelligence to collect even more information about drivers was field-tested by a coalition of Texas sheriffs.

Police cars often carry LPRs. Testimony in Schott’s case revealed where other cameras are placed to help law enforcement create detailed maps of individual motorist behavior.

“A lot of times at those mile markers, that's usually where LPRs are located,” Babb said. “You know those boxes that are on the highway where they, you pass and it shows the speed you're going? Those boxes also have license plate readers on them. So every time you pass one of those, your vehicle is also getting your picture taken and its license plate to show you're in that area.”

The WhatsApp report on Schott included more than just his route. “What it came down to was he left Houston with a female passenger,” Babb said. “He ended up going all the way to Carrizo Springs. What I was told was that he dropped a female off at a hotel.”

Asked how police knew that, Babb couldn’t say. “Homeland Security, DEA, everybody's there,” he said. “And they have a lot bigger toys than an LPR.”

The stop

Schott steps out of his car.

Court records

Interdiction flips traditional police work on its head. Instead of seeking a suspect who committed a particular crime, stop-and-searches identify a suspect and then look for the broken law.

To initiate the process, police require some legal reason to stop a vehicle. Transportation codes provide ample opportunity for so-called pretextual stops. The Texas version runs 3,000 pages.

“The beautiful thing about the Texas traffic code,” Babb testified, “is there's thousands of things you can stop a vehicle for.” That includes infractions like speeding, but also non-public safety violations such as a dirty license plate, too-tinted windows and an expired registration.

Driving outside the marked lane was a common choice for Bexar County’s interdiction officers. In recent years, the two-member team accounted for nearly a third of all lane violation citations issued by the sheriff’s department, Schott’s attorneys calculated.

Babb begins his questioning.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Yet deputies have struggled to prove Schott actually broke the law they said he did.

Records show Babb switched off his dash camera moments before Schott drove past; the only official record of the violation was his visual recollection. Babb turned his camera back on soon after the search, records show, a pattern for which he was later fired – and which the interdiction team apparently was known for within the agency.

“Bet ur dashcam didn’t catch it,” a sergeant texted a team member. “Sounds right for interdiction deputies.”

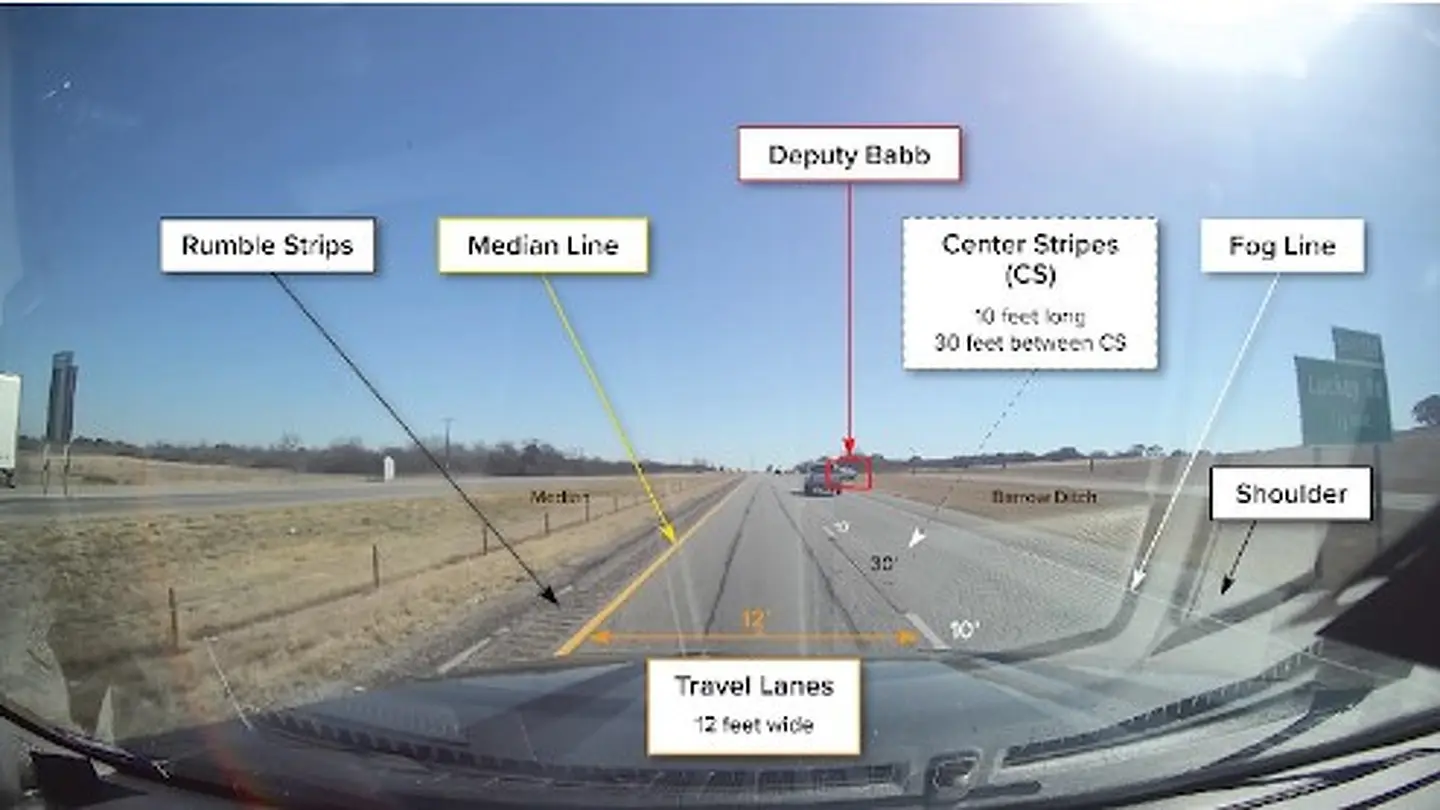

Schott, by comparison, had his own camera running when Babb pulled him over. His footage appears to show no obvious drifting. No rumble-strips sounds are heard.

Schott passes Babb, who was parked along Interstate 35.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

An expert hired by Schott’s legal team analyzed the recording, as well as the site where the stop occurred and Babb’s vantage.

An expert analyzed the deputy’s line of sight.

Court records

“As Mr. Schott’s truck approached Deputy Babb’s position, Deputy Babb could not have seen if the left wheels of Mr. Schott’s truck hit or minorly crossed the yellow line from his vantage point,” he concluded.

The interrogation

Police must clear several legal hurdles before searching a car. Schott’s stop illustrates how easily interdiction teams can overcome them.

The deputy's questions indicated the stop was about more than a lane violation.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Prolonging a traffic stop past the time it takes to issue a citation or warning requires officers to establish “reasonable suspicion” that something illegal might be going on. The factors must be specific, but the phrase still has plenty of wiggle room. Suspicious behavior cited by police in court cases has included signs such as looking at — or away from — an officer; inconsistent details in a story; a clean — or dirty — car; speeding — or carefully driving the speed limit; appearing unusually anxious — or unusually calm.

Babb’s first move was to direct Schott to sit in the sheriff's department vehicle while the warning was processed, instead of remaining in his pickup.

That allowed the deputy a chance to set up his body camera on the dash and grill him.

Deputy Babb's questions quickly become more pointed.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

A common shortcut to bypassing the legal tests required to search a vehicle is to simply ask the driver for permission.

Many searches occur after police simply ask permission.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

So-called “consent searches” make up the majority of police intrusions, said Derek Epp, an associate professor at the University of Texas-Austin who studies stop-and-search operations. Many people don’t know they can refuse.

Epp’s work also has shown consent searches are inefficient. “The departments that are doing more are not finding more contraband or crime,” he said. When counties such as Hidalgo and Starr dramatically increased the number of consent searches at the start of Texas’s border crackdown, for example, he found their hit rate — the times they found contraband as a percentage of the searches — plummeted.

Evidence gathered for Schott’s case appears to show the same pattern for the Bexar County Sheriff’s Office. “Over the past two years, the percentage of BCSO traffic stops that include searches has increased while the number of searches where contraband was discovered has decreased,” his lawsuit complaint charged.

Schott declined the search request. That meant Babb had to identify a legal reason to continue the operation.

The deputy described it in his deposition: Schott seemed anxious. When Babb approached the truck, for example, he raised his hands above the wheel. Also, “he was breathing hard. His chest was rising and falling. More so than the average person.” And, of course, there was the tip off from the WhatsApp group.

The traffic stop transitions into an investigation.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

The Texas Commission on Law Enforcement, which licenses Texas police, doesn’t require recruits to train on interdiction tactics. But there is a cottage industry of private training in which instructors combine their in-the-field experience with armchair psychology. Unlike some states, Texas does not require its state licensing agency to review and approve such programs.

In depositions, Bexar County’s interdiction team members cited several courses they had attended — “Evading Honesty” to develop “real-time detection skills for verbal and nonverbal deception,” for example, and “Vehicle Selection.”

The latter is put on by a large company called Street Cop. In 2023, the New Jersey comptroller’s office issued a critical report on the company's content after auditing a conference numerous New Jersey police agencies attended. A follow-up report this year found the state had spent $1 million on the company’s trainings over two years.

“Instructors at the Conference promoted the use of unconstitutional policing tactics for motor vehicle stops,” the report concluded. It cited instructors explaining how they had pulled over motorists for no legal reason, improperly prolonged traffic stops and conducted apparently illegal searches.

Excerpt from a 'Street Cop' training video that was sharply criticized by New Jersey officials.

New Jersey Office of the State Comptroller

In response to the comptroller’s findings, Street Cop founder Dennis Benigno described the instruction as “standard fare” and said he stood by the training.

The K-9 unit

Having identified the reasonable suspicion to prolong Schott’s stop, Babb’s next step was to meet the legal threshold for searching the truck — “probable cause” to suspect a crime. With no obvious sign of illegal activity, the deputy summoned the drug dog.

Babb calls for a K-9 unit.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

K-9 handler Dep. Martin Molina said he was nearby and on his way. A second interdiction deputy drove 90 mph to get to Schott’s truck within minutes, according to court documents.

The dog, Max, circled Shott’s truck. Molina said Max alerted on the driver’s side door.

The K-9 signals the presence of drugs at the driver's side door.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

But had Max really smelled drugs?

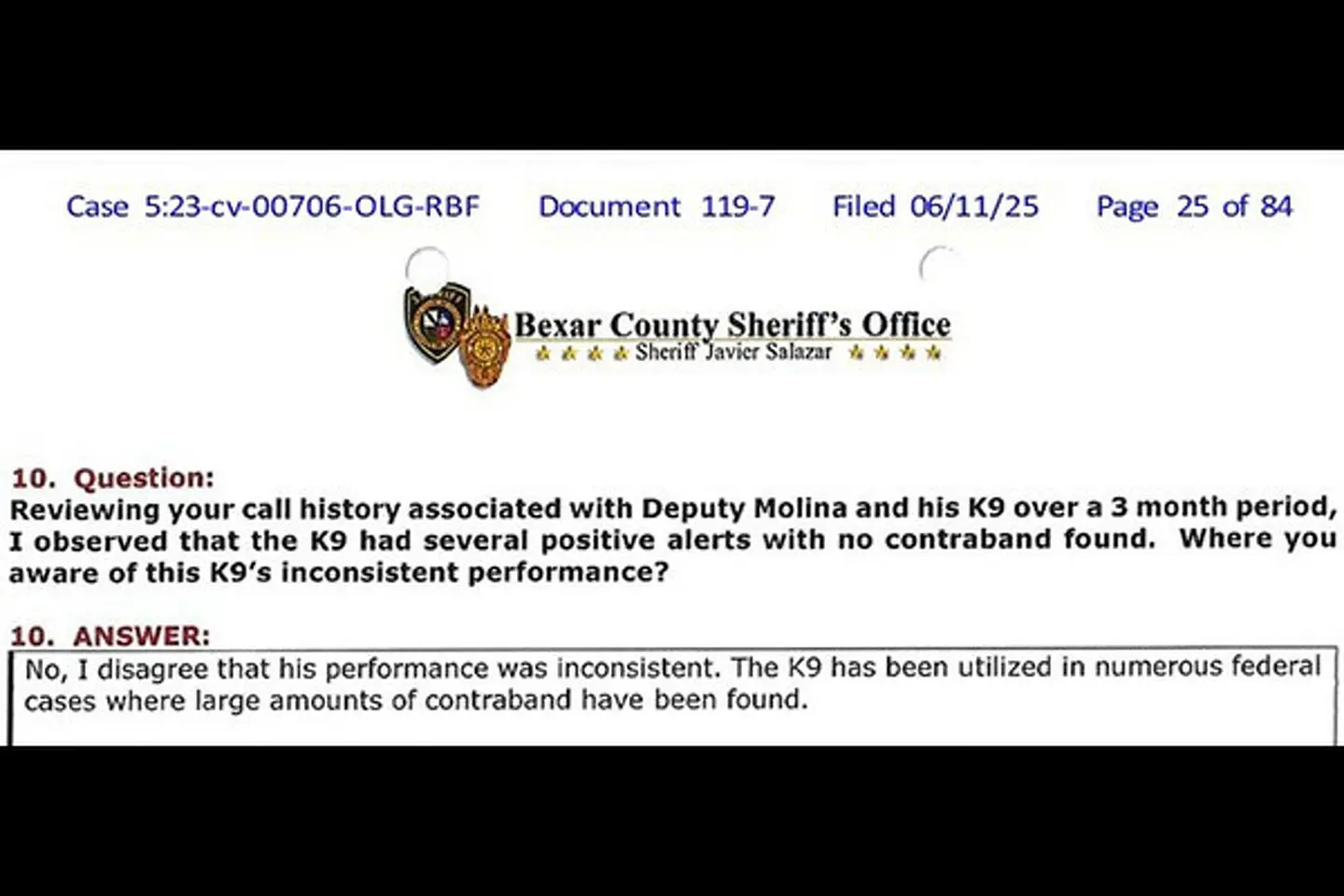

According to Bexar County’s testimony, Max was extremely reliable, with police finding contraband 90% of the time he alerted on a vehicle. A subsequent internal investigation into Schott’s stop, however, was less complimentary.

Bexar County sheriff's internal affairs document.

Court records

One possible reason: In his complaint, Schott alleged Max was trained to be rewarded simply for alerting on vehicles, rather than when drugs were found: “Molina, unlike other K-9 officers, manipulated Max’s reward structure so that Max would be cued to alert on cars regardless of whether drugs were present.” Molina has denied it.

There is also reason to question Max’s stats. Even when documents showed deputies had uncovered no contraband in a search after the dog alerted, Molina often wrote in his K-9 reports that he had found “trace” amounts of drugs, according to internal records entered into evidence in Schott’s case.

In other words, “Molina’s reports made it appear as if drugs were found nearly every time Max alerted,” Schott’s complaint alleges.

Molina also reported seeing specks of marijuana leaves in Schott’s truck — although he never mentioned anything during the search, according to his body camera footage. He never collected them or conducted any tests, he said in his deposition.

According to his testimony and video time stamps, here is when Molina said he spotted “very little small crumbs … specks” of marijuana in Schott’s vehicle:

A deputy said this is where he noticed drugs in Schott's truck.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

In his deposition, Molina defended all his trace drug observations during searches as accurate.

The search

Max’s alert qualified as “probable cause,” giving deputies legal permission to search Schott’s truck. Based on Babb’s reading of Schott’s body language after hearing the news, they were optimistic.

Deputies expressed confidence after the K-9 alert.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Three deputies rummaged through Schott’s truck — moving his children’s car seats, pushing aside diapers, opening his personal bags, pulling out the contents of his glovebox and center console. Deputy Joe Gereb, another interdiction team member, flagged “suspicious” signs of drug couriering in the truck bed and engine compartment.

Deputies didn't just look inside the car.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

But after more than an hour of being detained, questioned and searched on the side of the interstate, Schott’s truck was pronounced clean and he was released. Babb apologized for the inconvenience.

After finding no contraband, deputies acknowledged they seldom did.

Bexar County Sheriff's Office

Bexar County later sent Schott a check for $7,268.46 to cover damage to his truck during the search.

Deputy data editor Caroline Ghisolfi contributed reporting.