Graffiti Pier in Philadelphia, Photo by John Kidwell

I’m on a train in the French countryside. Sitting directly across from me is my brother Jim. We pass a centuries-old cottage in the middle of a field. The side of the cottage facing us features two words, each pitifully rendered in spray-paint on weathered stone. Before he settled down and started a family, Jim was once an extremely prolific graffiti artist whose work can still be viewed all over the post-industrial ruins of St. Louis City. He says that in the United States, you don’t normally see graffiti out in the country. It’s sort of an unwritten rule: writers don’t paint outside of metropolitan areas. I nod in agreement, adding that using historical structures as your canvas is… offensive isn’t the word… inappropriate? Jim agrees, and the conversation ends there.

Jim started doing graffiti when he was sixteen or seventeen. I can’t remember the precise year, but I’m sure he does; the way graffiti writers talk about the thrill of going out in the middle of the night to paint, I imagine the first time is not unlike losing your virginity—something one simply doesn’t forget. Jim started by driving with his high school buddies to St. Louis’ downtown flood wall, a remnant of the Flood of ’93 repurposed as a legal canvas for graffiti writers. Before long he graduated to bombing buildings, bridges, train cars, anything within the city limits. Jim worked jobs at gas stations and coffee shops and restaurants to afford a steady supply of spray paint and markers. Everything was his canvas, including the walls of his basement room, which he decorated with an all-caps SCAM, later painted over with his second and permanent anonym.

I think the reason my parents allowed him to spray-paint their basement is that they wanted to encourage any legal alternative to climbing city walls in the middle of the night. They’d lend Jim the family station wagon on the condition that he only go to the flood wall, knowing full well he would probably go someplace else, likely somewhere dangerous. As Jim got deeper into the graffiti lifestyle and eventually joined a crew, he grew more brazen. When we’d all go out to dinner as a family, I’d go to the bathroom and notice that he’d tagged the stall with a marker, or on the ride home, he’d nudge my arm and point to a billboard or a bridge and there it was: a massive, vibrant mural in all caps. A single word divorced from all meaning save for that of its inscription.

Which is not to say that I think graffiti is simple or easy. It takes enormous discipline for a writer to not only stick to one word but risk their lives for it. Right after I say that I find the graffiti on the old abandoned cottage inappropriate, I feel an instant pang of regret, like I’ve only just realized I sold out.

I wonder if Jim feels the same. I don’t think to ask him.

Important questions to consider when writing about graffiti: what do we mean when we use the word graffiti? What is graffiti? What isn’t graffiti? Is there a difference between good and bad graffiti? If so, what’s good and what’s bad? Is graffiti immoral or unethical? To what extent do morals and ethics matter when appraising a work of art? Should art be property? Should anything be property? What is property? What is art? What is beauty?

Graffiti is art.

This seems like a no-brainer, but there are people out there who truly believe that the vandalistic nature of graffiti negates any possible artistic merit. Though my appreciation for graffiti is not unconditional, I tend to take the opposite stance: graffiti’s transgressive qualities only enhance its aesthetic value. It’s art that bursts the seams, demanding that the world bend to it and not the other way around, refusing to comply with the arbitrary bounds of property law—those meaningless slips of paper meant to legally confer ownership of land, buildings, bridges, trains, and anything else that might serve as the artist’s canvas.

Still, I question how much beauty I see in this poor little cottage, which disappears from our view as quickly as it enters. Who would bomb a building like that? I imagine it’s young people. If I were a teenager in rural France with even a passing interest in graffiti, I probably wouldn’t hesitate to practice on even older relics. The targets of provincial graffiti aren’t all historic either. Bridges, utility boxes, road signs—nothing is safe. Graffiti written in a foreign language feels more abstract, the words somehow even more divorced from their meanings, since you’re never entirely confident of their meanings in the first place. In that sense, it’s a purer graffiti, because it all but forces you to approach it as a work of visual art rather than a work of logos. What does CLAS mean? Or ELOS? I don’t know, but check out those serifs—so wide and chunky, they almost look like little sidewalks.

I’m not an art critic, and as I type this, I feel like a bit of a fraud. I worry this reads like Matt Dillon in There’s Something About Mary, when he’s pretending to be an architect: Try to visualize the graffiti as a whole, to see it in its natural state, in its totalitarianism. Modern graffiti writers don’t have to worry about appearing verbose or pretentious, because they only need one word, which they can pick more or less at random. The word’s meaning should be, if not incidental, at least not the primary criterion for consideration. It should be about four or five letters, though suffixes and other forms of elongation aren’t necessarily discouraged in the appropriate context. The letters should pop: Ts like creeping anthropomorphic trees of black and white cartoons; Rs that buckle under the weight of their thick counters; sharpened As, Ms, Ns, Vs, Ws, and Zs, so menacing, always threatening to slice right through the other letters.

Whatever word one chooses, it should remain anonymous, which may be what most impresses me about graffiti: artists put themselves in insanely unsafe situations, risking arrest or worse, with the full knowledge that the glory of their accomplishments will remain mostly private, limited to the people they’re willing to let in on their secret. I can see what might’ve initially drawn Jim to graffiti: every graffiti artist is a superhero. Their work is, by nature, uncredited. It’s surely no coincidence that graffiti artists wear masks while they paint.

A vague memory, sometime 2002, 2008: my mom is dressed in all black, having just returned from a burial where, right across the funeral home’s tiny parking lot, in clear view of the attendees, my brother’s nom de plume was prominently displayed. She’s pissed, but behind whatever anger she’s feeling, I detect some pride as well. My son: the artist. You can’t walk a block in this city without seeing something of his.

Graffiti is vandalism.

Another no brainer. Graffiti is against the law almost everywhere. From the standpoint of deterrence, graffiti laws make sense, since the logical endpoint of unconditional legalization is a series of paint-plastered communities. Moreover, removing the element of risk from graffiti typically results in art that’s less practiced, less considered, less creative with its surroundings. Like the rules of the haiku, the constraints of graffiti—the hiding, the limited time, the need to do it at night—liberate the artist, and without these constraints, the art invariably suffers.

From a moral standpoint, the criminalization of graffiti is outrageous and indefensible. In Missouri, where Jim did most of his work, property damage crimes are divided into first and second degree offenses. First degree property offenses are confined to instances where the cost of repair exceeds $750. Second degree offenses are any other property crimes. First degree offenses are felonies and second degree offenses are misdemeanors; determining which classification applies is ultimately left to the discretion of the prosecutor. A repeat or particularly egregious offender could easily get slapped with a felony, and though I’m told it’s rare, jail time isn’t out of the question.

In researching Missouri and St. Louis property laws, two interesting things jump out: First, St. Louis City Ordinance #66934 prohibits not just “placing graffiti upon any public or private property within the City of St. Louis”, but also makes it illegal to “maintain graffiti that has been placed upon, or allow graffiti to remain upon, any surface within that person’s control, possession or ownership when the graffiti is visible from a public street, public alley, other public right-of-way and other public property.” This means that if a homeowner gets cited for displaying graffiti that someone else is responsible for, they are legally required to remove it at their own expense. Second, in 2017, the Missouri property damage laws (both first and second degree) were updated to include higher penalties for instances in which “the victim was intentionally targeted as a law enforcement officer… or the victim is targeted because he or she is a relative within the second degree of consanguinity or affinity to a law enforcement officer.” This amendment is part of a larger pattern of legislation in the US to punish anyone who challenges the police, even nonviolently—a disconcerting trend which also includes legislation to make the police a protected class under the Hate Crimes Prevention Act (already successfully passed in Louisiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Utah).

If you look past all the dubious arguments about aesthetic continuity and the reduction of blight, graffiti laws mostly boil down to outrage over perceived disrespect—for the prescribed order and presentation of public space, for property rights (except the right to address the defacement of said property in your own time), and perhaps most crucially, for the authority of the property owner. What graffiti’s most vehement opponents fail to understand is that it is often a direct reaction to the hallowed status of the property owner. As one anonymous gang leader noted in a 1979 New York Times article, “Graffiti writing is a way of gaining status in a society where to own property is to have an identity.” With the rate of homelessness at a record high, the resentment of (and rebellion against) private property should come as no surprise. Homelessness is a symptom of larger societal failures, while graffiti serves as both a commentary on and resistance to those same failures, which begs the question: is graffiti just one more example of art unfairly shouldering the blame for society’s ills? Do we all have a little paint on our hands?

Graffiti is protest.

France loves to protest. In fact, this is my first visit to the country in which I have not witnessed some form of public demonstration. When my family and I land at Charles de Gaulle Airport, the Paris Summer Olympics are just a few weeks away. I expect there to be lots of resistance within the city, but I don’t see a single sign. Even the activists here must prioritize their annual vacances.

France also loves rules. I’m pretty sure this goes hand in hand with its love of protest. France has rules about everything, especially wine: how many branches are allowed per grapevine, how many stems are allowed per branch, how much distilled alcohol vineyards are required to produce per harvest, what can and can’t be called Champagne or Bordeaux. Cheese also has a lot of rules attached to it—about when to serve it and how to cut it and in what order to eat it. When the French care about something, rules tend to follow. Maybe it’s a Catholic thing.

While French property laws are strict, Paris offers at least nine public walls where graffiti is permitted. It’s unclear if these sanctuary sites were established in response to an increase in graffiti or for other reasons. If they were meant to discourage graffiti elsewhere, it doesn’t seem to have worked. The city is covered in spray paint, more so than St. Louis or Baltimore or even New York. I’ll be the first to admit that the graffiti in Paris is excellent, probably as good as any city in the US. I wonder if this has to do with the Parisian penchant for protest, and if the relationship between French protest and French graffiti might be symbiotic. To be a graffiti artist means committing to something bigger than just yourself, not just your art but Art—art as life, art as air, art as an all-encompassing philosophy, art just for the fuck of it—and to protest is to practice similar commitment on separate but parallel terms. Though their aims are entirely different, art and protest cannot be severed from one another. They are the old couple going down with the ship in Titanic, forever entwined in ecstatic embrace.

Later, I’m humbled to discover that some of the earliest known ‘graffiti’ is in a cave in Lascaux, France. Thousands of years old. Maybe that’s why French graffiti’s so good: millennia of practice.

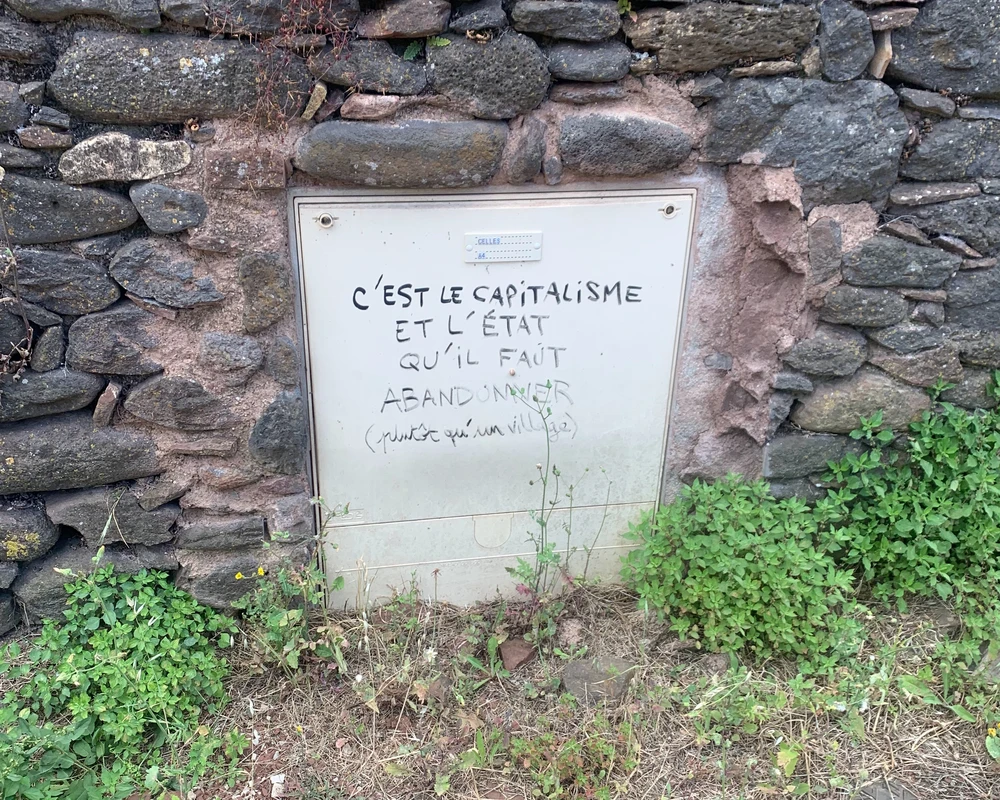

I’m still not all that impressed with the rural graffiti, though. I continue to question whether it’s appropriate in this setting. Even if it’s not a grave nuisance, I wonder if it’s perhaps a bit distasteful. I’m on the fence as we ride out to the ghost town of Celles, which sits right along the northern tip of Lac du Salagou. The town was abandoned in the mid-1960s for a dam that never happened and has remained unaltered ever since. It feels like it takes forever to get to Celles, winding up and down the hillsides around the lake, doing our best to follow the GPS map but still making a couple of bad turns that prolong our drive. When we finally arrive, it’s still a good fifteen-minute walk into “town”—limited to a handful of dilapidated buildings whose interiors are closed off from the public. There is one building that appears to be in decent shape, with actual glass windows, but it’s hard to see what the inside looks like in the bright sun. Almost all the buildings are marked with graffiti. I promised myself at the start of this vacation that I would stay in the moment and not take photos, but touring the ghost town, I make an exception for graffiti. There’s TEAZ in giant graded blue capitals, with little white clouds in the dark portion, the corner of the T partially missing after a wall collapse. There’s a faded orange Dest; I like the big cartoon D, the way the top part of the loop juts out the back like the blade of a tomahawk. There’s a boarded-up window with a little blue alien holding up his hands, as though pressed against a windowpane, opening his mouth and sticking out his tongue. On a utility box: a character shaped like a gravestone, dimpled smile, small catenaries for eyes, and a tiny baseball cap, just above the top of the head, as if flying off midair.

Then, behind one of the buildings, on another utility box that has been implanted into the wall of this centuries-old structure, in slightly faded black permanent marker: C’EST LE CAPITALISME ET L’ETAT QU’IL FAUT ABANDONNER. (It’s capitalism and the state that must be abandoned.) Parenthesized below in cursive: plutôt qu’un village (rather than a village). This is unlike the other graffiti I see in Celles. Aside from the obvious differences—multiple words, zero attention to presentation except for the switch from capital letters to lower-case cursive—this piece makes a markedly different impression on me than the others. It’s low, not in an obvious space, sort of like the ghost village of Celles itself, almost begging to be ignored. Unlike the rest of the graffiti I see in the town, it comments on its surroundings—not coyly, like the alien in the window or the happy little gravestone, but directly, firmly, in plain language that will not confuse anyone with a basic understanding of French. My initial reaction is cynicism: what kind of visitor sees this and has their mind blown by it? But as I stare at it for a few minutes, it dawns on me that blowing minds isn’t the point. This is a protest. It may be small and hard to see, and it’ll probably fade completely in a couple years’ time, but it’s still a protest. And if it doesn’t blow anyone’s mind, it still reaches me on some distant wavelength. After all, I’m still thinking about it. The little protest that could.

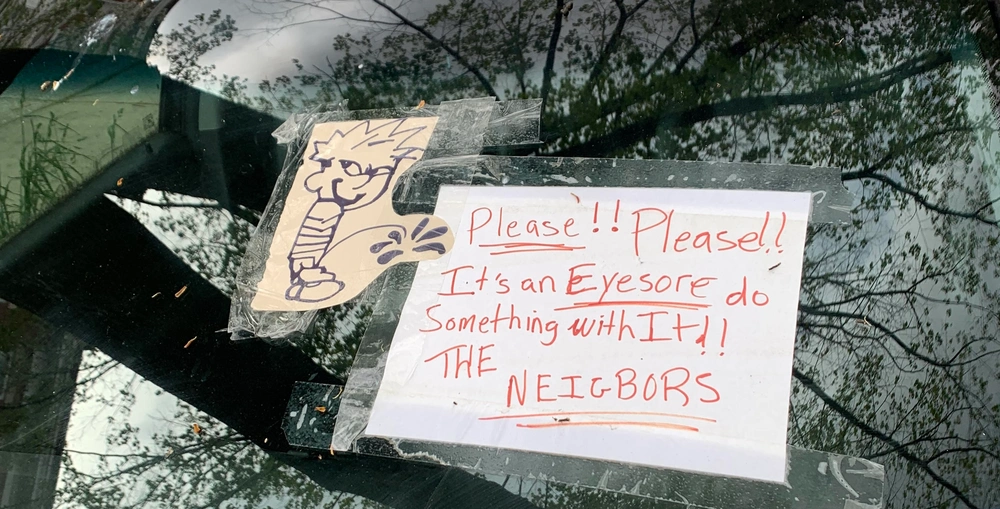

The protest of graffiti does not need to be grand or overtly political. Case in point: it’s April 2020, only about five or six weeks into quarantine. Since I’m not venturing out of the house much, my car has been parked on the street with a flat tire since the pandemic started. In the early days of a global pandemic, this does not seem like an urgent problem, but as I head down my block on the way to the grocery store one Saturday—remember those first few months of the pandemic when going to the grocery store was basically the only thing there was to do?—I notice a sign on my car, written in red ink on a sheet of plain white paper, affixed to my windshield with thick strips of clear packaging tape:

Please!! Please!!

It’s an Eyesore do

something with It!

THE NEIGBORS

I’m more amused than upset. I tell my girlfriend Caitlin about it, and we giddily speculate about the author’s identity. Caitlin wonders if it might be the work of some annoying thirty-somethings a few houses away, but I’m pretty sure it’s the old busybody who lives further down the block—the one whose advancing age is at odds with his affinity for cutoff jeans, who always says hi and, if you don’t reciprocate loudly enough, repeats HI! He’s exactly the kind of person who would do something like this.

A lightbulb appears above my head, and I dig up an old sketch pad. Turning to a clean sheet, I take about twenty minutes or so to freestyle a rendition of the iconic Pissing Calvin in permanent marker: looking over his shoulder, mischievous grin on his face, pants around his ankles, while a curved line shoots out from the other side of his bare ass, forming an arch before splashing into a collection of large, hastily inked cartoon piss drops. Not my best work, but it’ll do.

I take Pissing Calvin outside with a roll of Scotch tape and post it to my windshield, aligned with the neighbors’ note so that the piss splash is right between Please and It’s. I’m happy with my little protest, so I snap a photo and post it to Instagram. The comments are a mix of amusement, disbelief, and outrage—but mainly amusement: “Amazing”; “WTF. F them”; “Hahahahahahaha the only good Pissing Calvin I’ve ever seen”; “who tf puts tape on another person’s car”; “Neigbors.”

A day or two later, I find another note taped above the old one:

Piss on you when

Your car gets TOWED

The Neighbors

You have no RESPECT

Marveling at my neighbor’s latest offering, whose syntax and random capitalizations feel vaguely Trumpian, I consider how long I might keep this going, imagining an extended volley of notes and sketches that eventually papers over my entire windshield. Except I kind of want to use my car again. I tape one final note to the car, which I don’t think to record for posterity but is something to the effect of: Oh my God, chill out! I’m going to get the tire replaced later this week. Please relax, and do not tape any more notes to my car. Seriously, who does that?

I make good on my promise and get the tire replaced, and the matter is put to rest. I continue to see the suspect. One day, while washing my car for the first time in maybe a year—which includes scrubbing away the adhesive residue that he left on my windshield—the neighbor passes by in his cutoffs and tells me I missed a spot. I know it’s a joke, but I glare at him anyway, trying to make him feel as uncomfortable as possible. Attempting to smooth things over, he says that he used to wash cars for a living. I ignore him and continue my work.

That may sound petty, but is it any pettier than scolding someone anonymously via notes taped to their windshield? If anything angers me about the note incident, it’s that my neighbor was dishonest about his motives. It just so happened my car was parked in front of his house at the time, and his inability to park his minivan directly out front was obviously what started all this. If my busted Honda had been parked anywhere else on the block, I doubt it would have even come up. The issue was that my car was taking up public space that he believed, or at least wanted to believe, belonged to him.

This is all assuming I have the right person, which I might confirm or refute by simply confronting the individual and asking if he authored the notes. But I avoid any further confrontation, and when he says hi to me on the street, I meekly wave back and continue walking. Sometimes I miss our little back and forth, but so it goes. We’ll always have Pissing Calvin…

Stopping at McDonald’s on the way back from Celles, I mention to Jim and my sister Caroline that McDonald’s donates to the IDF. Not as a way of shaming anyone, but more like, Man, it sucks that you can hardly go anywhere or do anything without supporting genocide in one way or another. Driving away, I’m seized with shame, thinking about all the Palestinian people killed and starved and dislocated, imagining my whole family vaporized at the push of some vacant-eyed Israeli drone pilot’s button, wondering what it must be like to lose everything while I shove fucking French fries in my mouth.

On the way back to the Airbnb, the countryside graffiti looks different. The people riding these country roads can’t hope to completely escape the modern world in all its decay, blight, and neglect—all its ugliness, garishness, and artificiality. The graffiti forces them to look. It reminds them of where they really are—of who they really are.

And still, at the very same time, graffiti offers those same people a path forward, if they bother to look for it, as if to say:

Don’t look away!

Look at me, goddamnit!

I could be beautiful!

I am beautiful!

Graffiti is spectacle.

How else do I describe the angry Homer Simpson busting like Kong through the concrete sound wall across the highway—a trompe-l’œil the artist has rendered with a stunning level of verisimilitude—besides spectacular? The best graffiti makes you wonder how it was willed into existence. How does one create something so intricate and colorful? And so high off the ground! It can be easy to take for granted in a city like Paris, where graffiti is everywhere and has a way of blending into the background, but exiting the city, I see huge murals in the most precarious places, which require dangerous climbs onto tiny ledges, even rappelling. My mom says that’s the latest trend according to Jim. Graffiti writers wear harnesses and rope themselves down from rooftops to paint walls. My mom looks around at all the old Parisian buildings covered in graffiti and says it’s a real shame, covering such beautiful architecture with graffiti. I’m not sure I agree or disagree, so I just say yeah, I’ve been thinking a lot about that this past week.

What level of antiquity or historical weight must a structure attain such that using it for graffiti goes from an accepted everyday nuisance to a real shame? My garage in Baltimore is at least seventy years old, probably older, and the door was tagged somewhere around a decade ago. It’s still there, in black marker on white painted aluminum. I never cared enough to paint over it or remove it, and for the life of me, I still don’t know what it says. Is that a real shame? Or does the garage need to be at least a full century before the real shame sets in? When we see graffiti on a historic stone structure in the French country, is it any realer a shame than the highway from which we observe it, the roads that cut through lush hillsides like veins of tar? Is it any realer a shame than graffiti coating the walls of, say, a low-income housing project?

Graffiti is old.

Graffiti hasn’t always been so controversial. At a time when paper was extremely limited, graffiti proved to be a useful form of communication, with public walls serving as a sort of proto-civilized social media for denser populations. In Ancient Rome, for example, graffiti was used for practical, religious, and political purposes (memorably spoofed in Monty Python’s Life of Brian). Some Ancient Roman graffiti bear striking similarities to what one might find in today’s bathroom stalls, as was the case with one recently uncovered inscription: Secundinus cacator, which roughly translates to “Secundinus, the shitter.” It wasn’t until 1851 that the word graffito was even coined, in reference to the walls of Pompeii. From early cave paintings to Kilroy Was Here, graffiti was fair game, and only relatively recently has the word become synonymous with defacement and vandalism. It would seem logical to assume that graffiti’s transgressive and unremunerative nature automatically places it in opposition to the status quo, but is that truly the case?

In the context of the neglected, often boarded-up city properties that serve as its primary targets, graffiti may preserve the status quo on some level. It’s the spoonful of sugar that helps blight go down a little easier: isn’t that cute, a little cartoon character climbing out of the smashed window, how adorable—just watch out for that needle there by your foot, honey. However, neglect is only part of the equation. One person’s harmless visual distraction is another person’s proof of a neighborhood in decline, turning decoration into further justification for erasure. When plans to restore blighted areas pose even the slightest challenge, demolishing historic buildings is standard practice, and graffiti only strengthens the case for condemning beautiful, still-viable structures and replacing them with architectural monstrosities.

Nevertheless, I have a hard time balancing the premise that graffiti serves the authoritarian status quo with the overwhelming sense that it does just the opposite—that it serves to highlight the status quo’s resounding failure. When the graffiti artist bombs a rich or gentrified area, the message is:

Fuck your property values

Fuck your condo association

Fuck your lofts and your juice bars

Here’s some art

You’re welcome

When a graffiti artist bombs an abandoned house, the message is basically the same except inverted:

Fuck your car

In which you drive past me day after day

With nary a glance from your highway and

Oh yeah—fuck your highway too

Here’s some art

You’re welcome

Graffiti is art criticism.

From an earlier version of this essay, titled “Painting of a DJ at Turntables (sold at Target)”:

This painting approximates graffiti art, a tradition that exists as 1) a graphic extension of a given environment, and 2) a subversion of/rebellion against the ordered aesthetic of that environment. I’ve always felt ambivalent about graffiti (or “street art,” a sanitized euphemism) going on display in galleries: on one hand, it gives the artists a chance to make a living on their art; on the other hand, it takes something that is supposed to exist in the wild and tames it, forces it inside a box. To see what might lend some beauty to the side of a cargo train trapped on a three by four-foot canvas is like seeing a tiger in a cage. It’s heartbreaking … When my brother started going out at all hours of the night to paint dilapidated buildings in downtown St. Louis as a teenager, I doubt he ever really thought it would bring him riches. I think he just thought that doing graffiti was fun and exciting and a little dangerous, which is probably still how he feels. When people try to make money off graffiti, it feels desperate, and that desperation bleeds into the images themselves. When I see graffiti art on a canvas or adorning the interior walls of a craft brewery or some taxpayer-funded “creative hub,” I don’t see anything fun or exciting or dangerous. I see a Sprite commercial.

The morning after I return from France, I start working on this essay in its present form, and after a few hours of writing on my bed—God, I missed my bed—I go for a short drive. Not anywhere in particular, just riding Cathedral Street downtown before heading back up Charles Street. At North Avenue, I pass the giant billboard that stands over Larry Hogan’s former gubernatorial campaign office. The billboard has taken on many faces during its lifespan, their shifting expressions a perpetual tug of war between its renters and graffiti artists. The earliest incarnation I can recall was just after Freddie Gray was killed. It said WHO EVER DIED FROM A ROUGH RIDE. Then below, in much smaller letters: THE WHOLE DAMN SYSTEM. That stayed up for a long time, but eventually it got replaced with something else, something not particularly memorable, possibly another campaign ad, and eventually that came down and got replaced by DEFUND BPD, in reference to Baltimore’s Police Department.

My sense is that if I drew a Venn diagram of graffiti’s biggest opponents and those driven apoplectic by the abolish/defund movement, it would basically be a circle. The kind of people who hate graffiti need the police to be their enforcers. Here in Baltimore, defunding the police is not just a pipe dream for leftists, unlikely though it may be. In the wake of Freddie Gray, the Gun Trace Task Force scandal, and the millions of taxpayer dollars spent settling police brutality lawsuits, Baltimore is desperate for any alternative to its current model of policing. In a 2020 survey, 57 percent of respondents stated that they were very dissatisfied with the Baltimore Police Department, with a total of 64 percent responding negatively to the question; only 4 percent said they were very satisfied, with a total of 16 percent responding positively. Of the 711 respondents from a 2023 poll, 75 percent were in favor of allocating funds from the police to social, mental health, and drug treatment programs (though, curiously, 48 percent of respondents in the same survey said funding for the police should be increased, with only 16 percent saying it should be decreased). Unsurprisingly, a more recent report also shows major discrepancies between black and white Baltimoreans’ experiences with the police: “There was a significant strong relationship between the race/ethnicity one identified as, within the purposive sample, and their feelings of safety in Baltimore city and their observation of BPD using verbally abusive language towards civilians.”

When I see DEFUND BPD hovering above North Avenue in enormous, spray-painted letters, I don’t see the opinion of one idealistic graffiti artist; I see someone expressing an increasingly common sentiment. I detected a similarly popular opinion early in the pandemic, after a campaign billboard for interim mayor Bernard Young replaced DEFUND BPD, when an artist—possibly the same one who did DEFUND BPD, as the letters looked very similar—covered over the text with a giant CANCEL RENT, making it appear as though the demand was coming from Mayor Young himself. Unsurprisingly, Young’s office saw to power-washing the billboard as quickly as it could, and it remained graffiti-free until late 2023, when a large FREE PALESTINE appeared. In the wake of October 7, as the Israeli government escalated its extermination of Palestinians, this wasn’t just some trendy slogan for a cause celèbre but, rather, a desperate plea to anyone who would listen. Yet just as suddenly as FREE PALESTINE materialized, it was replaced by the billboard’s most hideous manifestation: a graffiti-style mural that reads INSPIRE CREATIVITY.

INSPIRE CREATIVITY is the quintessence of Sprite commercial shit, co-opting the visual trademarks of a wild and rebellious artform—linked letters, little glimmers of reflected light in the corners of certain letters, arrows pointing in every direction—toward something anodyne, sanitized, and commercial. I have no idea who put up INSPIRE CREATIVITY, but considering its size and detail, I assume it was officially sanctioned—likely part of the ongoing effort to revitalize North Avenue, whose stubborn reputation for crime, homelessness, and blight has been a major obstacle for its slowly diminishing storefronts and restaurants. Not long after INSPIRE CREATIVITY was finished, an amendment appeared just below CREATIVITY: Oh and… FREE PALESTINE!!!! The first time I drove by it, I laughed out loud. I think it was the Oh and… that got me—how the artist didn’t even try to conceal their contempt for the shitty mural they were defacing. All graffiti is art criticism, due to its relationship with architecture and sculpture and so many other elements of the urban environment that fit under the broad umbrella of Art, but this was different—its critique more pointed, direct, even personal (which, according to the most annoying people on the planet, is always political). Similar to the anti-capitalist graffiti in Celles, this was the rare piece that channeled all the energy that might normally go into a work of graffiti—all the attention to layers and color and arrows and linked letters with the little glimmers of light in the corners—into a concise political critique, punctuated by quadruple exclamation points, like it was screaming at the previous muralist:

This shit doesn’t fool me!

How stupid do you think I am?

Not that stupid

Oh, and… FREE PALESTINE!!!

Graffiti is poetry.

When I send an early draft of this essay to a friend, she asks why the voice of graffiti is written in verse. I tell her that I didn’t have any specific design when I wrote it that way. It just felt right. Only in retrospect do I realize the obvious reason for using verse instead of prose: graffiti is poetry. I don’t mean that graffiti is literal verse, nor is it poetry in the way people say Terrence Malick movies are poetry; it’s closer to what Lou Reed referred to as “a spirit of pure poetry,” this idea that art, literature, performance, nature, music—all the beautiful things that give our lives meaning—are each part of a whole, residing under the same roof, in much the same way that the state, the police, the corporations and the condo associations and the lady who posts on Nextdoor about homeless people also live under the same roof.

What would a world without graffiti look like? Better question: what would a world without the need for graffiti look like?