Figma is committed to building a secure and seamless environment for our users and employees. As part of this mission, we recently scaled Santa, an open-source binary authorization tool, across all Figma laptops.

One of the biggest objections to binary authorization tooling is that it can be very disruptive for employees. We had those concerns, too. Here’s how we use Santa to strengthen our endpoint security while ensuring Figmates can stay in the flow of their work and access all the tools they need every day. We’ll cover how we got started with Santa, tips for building a data-driven ruleset using monitoring mode, how to give users self-service tools to get unblocked, and the staged rollout plan that helped us avoid disruptions.

To learn more about how we design our corporate security with the user experience in mind, check out our article on Figma’s modern endpoint strategy.

Malware on endpoint devices is a common entry point for cyberattacks, often serving as the first step in large-scale data breaches. Binary authorization is a process that restricts devices to running only approved applications. It doesn’t cover non-binary code, like scripts, extensions, or plugins that an allowed binary can run, so it’s only one part of a layered security approach. But binary authorization significantly reduces the attack surface, because security teams only need to vet, harden, and monitor applications within the allowed set.

Santa is a macOS security tool originally developed by Google that enables binary authorization. You can use Santa in either monitoring mode, where it passively records data about binaries, or lockdown mode, where it applies a set of allowlist rules.

It’s worth noting that Santa also supports file access authorization (FAA), restricting access to specific files and ensuring that only approved applications or processes can interact with them. We’ve leveraged this to secure browser cookies on Figma laptops—a prime target for attackers. By locking down cookie access to only the browser application, we significantly reduce the risk of credential theft, even from scripts attempting unauthorized access.

Since it has essentially zero impact on users’ workflows, we implemented FAA first to get an early win. Once Santa was deployed to Figma’s fleet for FAA, we took the next step: turning on Santa in monitoring mode to inform our plans around binary authorization.

Santa’s allowlist supports multiple rule types:

Binary: Use a binary’s hash (SHA-256) for precise control. Any tampering of the binary on disk invalidates the rule.

TeamID: Permit all binaries signed by an Apple developer team (e.g., Google’s EQHXZ8M8AV).

SigningID: Allow binaries signed by a specific developer signing identity (e.g., EQHXZ8M8AV:com.google.Chrome).

Compiler/Transitive: Automatically allow binaries created by specified compilers, ideal for development environments.

PathRegex: Allow or block based on file paths. Use sparingly due to bypass risks.

Laying the foundation: Santa in monitoring mode

We were initially unsure whether we could roll out binary authorization with minimal disruption to Figmates. So we started by deploying Santa in monitoring mode across our fleet. This allowed us to collect data on every binary execution without blocking anything. The insights were invaluable, revealing patterns in how our team used software and helping us craft a tailored allowlist.

We started with SigningID and TeamID rules, which leverage Apple’s developer certificates to identify trusted applications and publishers. By creating rules for our Figma-approved applications (e.g., Zoom, Slack, Chrome, Notion, and GitHub), we were able to cover the majority of binary executions on Figma devices. Encouraged, we analyzed the remaining data to refine our allowlist and prepare for lockdown mode, where unapproved binaries would be blocked.

TeamID vs. SigningID: Navigating the tradeoffs

Building our global allowlist revealed nuanced tradeoffs, particularly when choosing between TeamID and SigningID rules. TeamID rules, which permit all binaries signed by a developer’s Apple Developer Team ID, simplify management for applications with multiple Signing IDs—common in apps with separate executables for main binaries, helper tools, or update mechanisms. Maintaining individual SigningID rules for each component can be labor intensive and risks missing when updates introduce new Signing IDs.

However, TeamID rules are inherently broad because they correspond to an entire company. For example, allowing LogMeIn, Inc.’s Team ID (GFNFVT632V) for GoTo Meeting would also permit LogMeIn Rescue, a remote access tool. SigningID rules offer precision, ensuring only specific application identities are allowed.

Our approach to balancing this tension was to default to SigningID rules, reserving TeamID rules for highly trusted developers with suites of apps we wanted to allow or complex apps where managing multiple Signing IDs was impractical. To mitigate Team ID risks, we implemented a more rigorous review process for new TeamID rules, analyzing the developer’s application portfolio to ensure no unintended binaries were allowed.

Expanding our allowlist

When analyzing the remaining UNKNOWN events in monitoring mode (binaries that would be blocked in lockdown mode), we identified three main categories of findings:

- Binaries signed by an Apple Developer identity (“developer-signed”) for which we didn’t yet have a TeamID or SigningID rule

- Unsigned (including

adhocsigned) binaries built locally - Unsigned binaries from package managers or repositories (e.g., Homebrew, Terraform plugins, npm, GitHub releases)

To address these, we took a multi-pronged approach:

- Proactive review: We reviewed developer-signed applications installed on more than three devices, categorizing them into global allow rules or global block rules. For apps that didn’t fit into either category (for example, a personal finance app that didn’t have a business use, but would be OK to allow on a per-user basis), we decided to block the application initially, but allow the user to approve it in a self-service manner—more on this later!

- Compiler rules: We added rules for compilers to cover locally built binaries, ensuring developers could work uninterrupted.

- Package rules: Packages distributed through tools like Homebrew posed a challenge—updates would change a binary’s SHA-256 hash, triggering blocks. To solve this, we created a custom Package Rule system.

The Package Rule workflow

Our Package Rule system dynamically generates Binary (SHA-256) rules for packages from their official sources like Homebrew or GitHub. Here’s how it works:

- For each package, we define a Package rule with a

package_type(e.g.,homebrew) and identifier (e.g.,vim). These rules are defined in the same GitHub repository where we manage the rest of our Santa global rules and configuration as code. - A custom workflow fetches the latest SHA-256 hash from the official source or downloads the package to compute it.

- The workflow runs every 30 minutes on macOS runners to ensure rules stay current. It’s important here to use the same architecture that you support within your fleet—ARM, x86, or both—to get the correct SHA-256 values.

- New Binary rules are distributed to the fleet, preventing blocks when packages update.

Example Package rules:

JSON

[

{

package_type: "homebrew",

package: "vim",

},

{

package_type: "github",

package: "rust-lang/rust-analyzer",

}

]Minimizing disruption: A user-centric approach

As outlined in our previous post, security must balance protection with usability. Before proceeding with the rollout, we looked for ways to minimize disruptions for employees.

A sync server is used to programmatically update and distribute Santa rules and configuration to a fleet of devices. We built customizations on top of the open source sync server Rudolph.

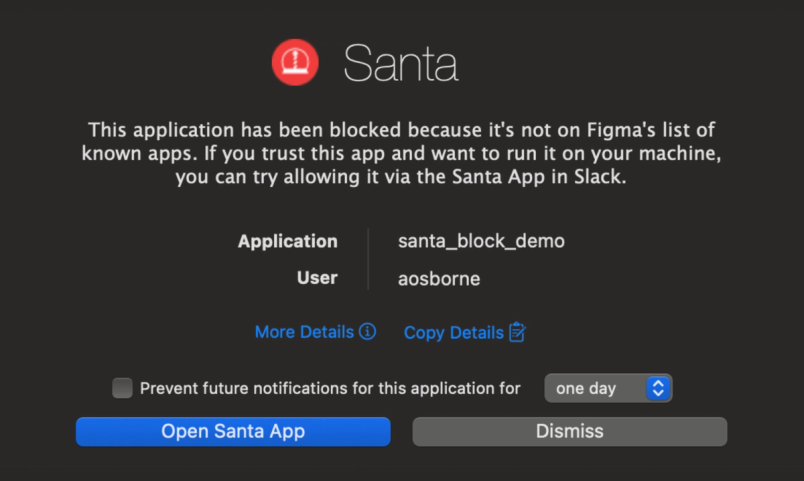

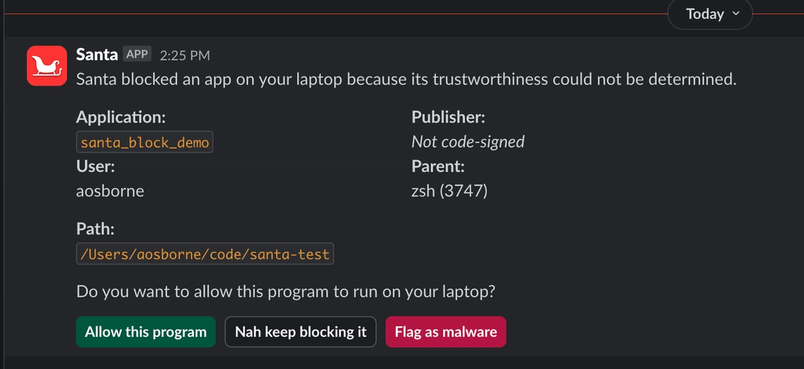

Due to our work developing an allowlist in monitoring mode, we believed that blocked binaries should be rare. But when a binary is blocked, users need a fast, intuitive way to resolve the issue. Instead of customizing Santa’s client-side GUI, we leveraged our Enterprise Slack—accessible exclusively on Figma-managed devices—as our primary interface.

When Santa blocks an application, the sync server receives the block event and checks the binary against malware databases (e.g., ReversingLabs) and other risk and policy indicators.

Our custom Santa Slack app also offers flexibility to impose stricter policies as needed, e.g., for users whose roles make them more likely to be targeted by attackers.

If those checks pass, the user receives a Slack message via our custom Santa app, offering options to either approve the application (which creates a machine-specific rule), do nothing, or flag it as malware.

If the app fails our checks, the user is notified that it was blocked, with the option to follow up with the security team if needed.

Ensuring fast rule sync

To ensure approvals take effect quickly, we faced a challenge: Santa’s default sync interval (60 seconds) was too slow, leading to repeated blocks. Google’s internal solution for Santa at the time used Firebase Cloud Messaging, but this wasn’t publicly available. As a workaround, we developed a package that can trigger the santactl sync command on a device via an API call to our MDM server, allowing the device to retrieve the new self-approved rules. This reduced the time from approval to rule enforcement to around three seconds.

Limits on self-approved applications

While Santa’s self-service flow empowers users to approve new applications, we maintain other limits on these self-approved applications to ensure meaningful security outcomes, particularly around macOS TCC (Transparency, Consent, and Control) permissions. If an application requests sensitive permissions like Accessibility or Full Disk Access, our endpoint security system (built on osquery) automatically detects and unsets the new permission until the security team reviews it.

After review, we update Santa’s rules and our application permission allowlist. We may decide to globally block an application due to the new permissions it requests—these cases, while rare, will require users to follow up with the security team for approval.

Rolling out Santa: A phased approach

Communication was key to a successful rollout. At a company all-hands, we presented real-world examples of breaches caused by endpoint malware, explained why Santa mattered, and discussed how to handle blocks.

We also knew some users might encounter excessive blocks during the rollout, so we built an escape hatch. Using the Slack command /santa disable, users could temporarily switch their machine to monitoring mode. This allowed us to investigate and resolve issues without disrupting workflows.

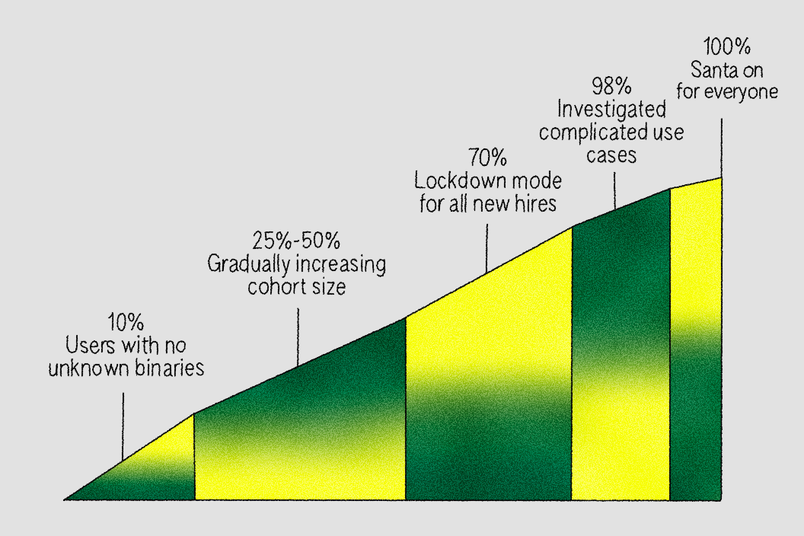

We rolled out lockdown mode in phases, across a total timeframe of around three months:

- 10% cohort: We started with users who had zero unknown binaries in the past month.

- 25%, 50%, and 70% cohorts: We gradually included users with fewer than 10 unique unknown binaries, addressing issues as they arose, and enabling lockdown mode for all new hires when we reached the 70% mark. The final 30% included engineers and data scientists, and because of the tools they use, creating rules for these groups was more difficult. As one example, Anaconda signs each Python binary locally with

codesignad-hoc signing in the user workspace, generating unique hashes per machine. Options like a Compiler rule forcodesignor a PathRegex rule for the Python binary’s install path were more permissive than we wanted fleet wide. We addressed this by enhancing our sync server to support group-based rule sets, scoping permissive Compiler or PathRegex rules to specific groups needing these tools.

Figma’s Endpoint Security Baseline (ESB) is a set of security controls that keep corporate devices secure. ESB enforces security policies, preventing out-of-compliance devices from accessing internal systems.

- 98% cohort: Having onboarded most of the company, we paused for a month to investigate machines left with more than 10 unknown binaries and those that used the

/santa disableescape hatch, adding global, group, or machine-specific rules as needed. - 100% cohort: Once we hit 100%, we retired the

/santa disablecommand and made lockdown mode part of our Endpoint Security Baseline.

Santa in action, one year later

After over a year in lockdown mode, here’s what Santa looks like at Figma:

- 100% fleet coverage: All laptops in lockdown mode

- Global allowlist: ~150 rules (e.g., Slack, Zoom, Chrome) using Signing ID and Team ID

- Global blocklist: ~50 rules, including software like unapproved remote access tools

- Package rules: ~80,000 Binary rules generated from our ~200 Package rules

- Compiler rules: ~10, supporting developer workflows

- PathRegex rules: ~50, tightly scoped to minimize risks but used expediently for rollout; we aim to reduce these over time

- Personal rules: Median of 3 per user

- P95 blocks per week: Steady state of 3–4, with over 90% resolved via self-service

We’ve had to navigate a few roadbumps along the way. For one, as Package rules grew to ~80,000 Binary rules, initial sync times for new machines reached several minutes, occasionally causing connection drops mid-sync. This left devices with incomplete rule sets, blocking apps that should be allowed.

We mitigated this by adding static allowlist rules in the configuration for critical applications (e.g., MDM, Chrome, Slack, and Zoom), ensuring functionality regardless of sync state. Over time, we’ll continue to improve Package rule maintenance, with work planned to expire rules for older package versions and improve sync performance.

One of our pain points with Santa has been a particular edge case for Compiler rules in the case of using go run during local development (detailed in this GitHub issue). In short, Compiler rules work when using go build and then running the binary created as a result; but using go run to compile and execute the binary immediately creates a race condition where Santa isn’t able to create a Binary rule for the compiled binary before it’s executed, resulting in a block for the user. We’ve worked around the issue by updating scripts to avoid go run or adding PathRegex rules for now.

Key takeaways for your Santa rollout

If you’re considering a binary authorization rollout with UX as a priority, here’s what we learned:

- Include an escape hatch: Allow users to switch to monitoring mode during the rollout to derisk disruptions.

- Automate package updates: Build a workflow like our Package Rule system or manage package versions centrally to handle frequent updates.

- Avoid path-based rules: Opt for Compiler or Package rules whenever possible, and when using path-based rules, scope them tightly to specific paths and only the machines that require them.

- Monitor and alert: Proactively track block events (e.g., more than three blocks per day) with alerts to assist users before issues escalate. Monitor rule counts to ensure devices sync all rules, preventing incomplete sets that cause unexpected blocks. Alert on sync failures to detect machines not connecting to the sync server, ensuring the self-service approval flow remains functional.

- Stage changes with pilot groups: Santa version updates or major configuration changes can disrupt users. Mitigate risks by testing these changes with a small pilot group first. Our pilot approach has repeatedly caught potential issues early.

Rolling out binary authorization across Figma’s fleet was a significant step in strengthening our endpoint security. By combining data-driven rule creation, automated workflows, and a user-friendly self-service model, we achieved robust protection with minimal disruption. We hope our journey inspires others to explore binary authorization as a powerful tool for securing their fleets.