I am an addict. No joke.

After a full workday of writing code, I come home and hack on side projects. It's not healthy and I’m the first to acknowledge it. This is a real addiction, but is not taken seriously since its seen as “one of the good ones”.

What’s changed recently isn’t how much I build, but how I build.

For builders, there is that dopamine hit when many hours of effort turns into something that works. But now those hours can be compressed into minutes with almost no effort. All the dopamine you could ever want. Dangerous.

But I’m not here to talk about addiction.

Waiting used to be optional

Discovering Linux and open source was a revelation to me when I was younger. The idea that almost all of the world’s software was freely available, constantly improving, and instantly accessible felt unreal. Even utopian.

My father was an architect. He would spend months, sometimes years, designing buildings, and only much later see the result. I couldn’t imagine waiting that long to experience the payoff of my work.

I see a similar dynamic with my kids. They build and rebuild the same LEGO sets, but the desire for the next thing is always there. Once you’ve assembled everything you own, you have to wait, or save, before you can build something new.

Software removed waiting. The internet was an endless playground of toys to try. That immediacy shaped how I learned, how I worked, and what I found satisfying.

New builders, new entry points

That same removal of waiting hasn’t just changed how experienced programmers work, it has lowered the barrier for who gets to build at all.

One of the great things LLMs have done is empower non-developers. People can now build tools for their own needs without years of training, and you don't need to be a super nerd like me.

I love seeing what this new community has come up with, even if that accessibility may not last for ever.

The journey is shrinking

For me, programming used to be mostly about the journey. I would make incremental changes, hit dead ends, rethink abstractions, and slowly converge on something solid. Programmers love to solve puzzles.

Lately, I spend more time adjusting test methodologies and iterating on design documents with an LLM than writing code directly. The destination is cheap, so the journey matters less. That’s especially tempting for things I’ve built so many times before (auth flows, CRUD APIs, server caching, etc).

Models today can readily implement complex end-to-end features in no time. I recently wanted to add a text to speech flow to my reader app. After a few minutes of design discussion, Opus produced a complete, working flow with widgets, real time feedback, and graceful degradation. In the past, this would have taken most of a day to code.

The cracks show up elsewhere. Testing remains uneven. It has improved a lot, but still tends to optimize for code coverage with weak assertions rather than meaningful tests. It will even rewrite tests with inverted assertions just to make them pass against new code. Weird behavior, but newer models will certainly fix these issue shortly.

Keeping things DRY is another persistent struggle. Even frontier models still lose the big picture when working on specific features. When a core function should be shared across the codebase and I ask for updates, the LLM often duplicates the logic and tweaks it in only one place. No amount of rule setting seems to prevent this, and the weak testing (see above) is quite good at letting these issues go unnoticed until too late.

I get more done, but I spend less time thinking in code. That tradeoff shows up again and again as I look at what this kind of productivity does to how I work.

Making beautiful code or an elegant abstraction

As the journey compresses and more of the work happens at a distance, something else quietly erodes alongside it: the attention we once paid to the shape and feel of the code itself.

I have tried being very descriptive to the LLMs about how I want my code to be written, but it can only get you so far. And why bother? The better these tools get, the less time I spend actually looking at the code itself.

You can spend a lot of time curating you Claude hooks, skills, etc. But these are just stopgaps while the models improve with each release. In a few months' time no one will be context hacking as these models get smarter than us seasoned engineers.

At the time of this writing I am using Opus 4.5 and it needs dramatically less handholding then its predecessors.

Productivity and its cost

I’ve shipped more side projects in the last couple of years than ever before. I don’t even write ideas down anymore. I just spin up a discussion with Claude Web and pick it up later on my phone when walking the dog.

That acceleration has pushed me toward building more feature-complete apps. On a recent project, I was so satisfied with the LLM performance that I had it translate the entire application into multiple languages. I am the only user. I only speak one language.

The downside is cognitive. When you have a cloud of minions waiting to execute your every command, downtime can feel outright senseless. Managing parallel agents and half-started ideas takes real mental space. Productivity becomes something you have to manage, not just enjoy.

This kind of productivity has a different cost profile than manual work.

Any developer who’s become a manager knows the feeling: distance from the code reshapes how you think. I’m learning new skills, but spending less time in syntax and implementation can feel like a kind of intellectual atrophy. Fewer sharp edges, less resistance. At the same time, this new over-productivity feels almost greedy.

Innovation for humans?

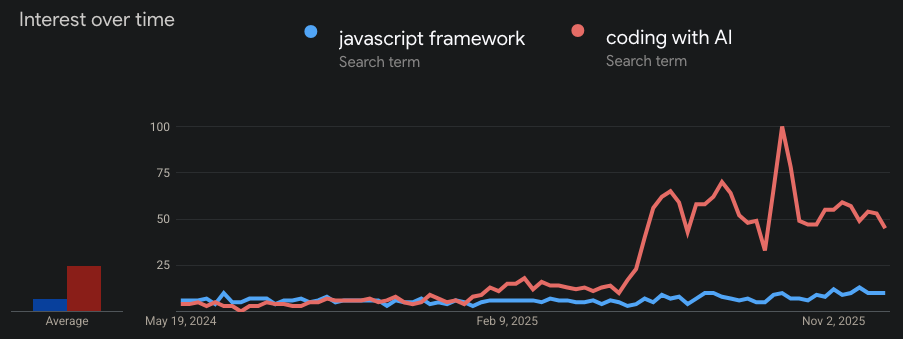

I feel less excited by new languages or frameworks than I used to, possibly because I spend less time reading and writing code directly. If humans stop being the primary audience, it’s unclear what happens to ergonomics, fun, or beauty as code design goals.

It is funny to think future advanced AI may still be programming on ancient 21st century technology, happily solving everything with pseudocode instead of ever needing a Python 4.

What language innovations do I see these days? LLM focused ones that center on using string compression to deal with limited context windows. I don't find this terribly interesting, but this is early days for these languages.

I think LLMs would do better creating their own i-code that makes the most sense to them. Maybe its all Sanskrit and emoji. Who knows.

At some point, LLMs became generally good enough at writing programs. For many tasks we have surpassed that.

Early in your career, it’s natural to obsess over unnecessary details. naming, structure, theoretical purity. Over time, you learn a different lesson: most of the code you write will be replaced in a year or two anyway. Given that reality, “good enough” isn’t a failure of standards; it’s an acknowledgment of impermanence.

What's next for us?

There have always been programming hobbyists who don't do it for their job. They are in the minority, but probably not for long.

I have been very lucky to have a career where I get paid for doing what I love. And it's truly been an honor to work at interesting companies, with great missions, and some brilliant people. These days at work I am getting pull requests from non-technical coworkers.

Sure, the product manager can't run our stack, but he can fire off an agent to make changes to widgets or even vibe code a whole new product idea. And why not? Much of this is boiler plate grunt work we would rather not do anyway.

There will be professional programmers for a while yet, but fewer and fewer will be needed or employable.

What a blow it will be when it is taken away from us. I guess we will join the other droves of white collar workers being forced into an early retirement. Even if my run of making a living from it has run its course, I'll still be coding away. And I'll still be addicted.