Linux - Recreating old problems with new tools

Updated: September 5, 2025

The Year of the Linux (desktop). Can it happen? Will it happen? For about two decades, the Linux desktop market share hovered around the magical underdog figure of about 1%. No matter what the Tux folks did, the needle wouldn't budge. More recently, there's been some growth in the desktop share. This is primarily thanks to Steam and their hard work on the Proton compatibility layer, which lets you play Windows games as if natively on Linux. As a result, with that one major obstacle removed, more and more people are slowly, gradually switching to Linux. My own journey shows some rather nice results. It would seem we have finally turned a page.

Alas, just as we've reached some small level of stability, some small level of progress, there's a good chance all of this effort will have been in vain. What do I mean by this? Well, the Linux world is fragmenting once more, on several levels. Rather than consolidate powers, or at least, not add more chaos into an already chaotic market, we shall now see a proliferation of new package formats, new distributions, new everything. This repeating of history comes at the most inopportune moment, and jeopardizes the Linux success story.

Note: This image was taken from Wikimedia, by Serge Ouachee, licensed CC BY-SA 3.0.

Atomicity, you keep using that word

In the recent years, there's been an explosion of new, exotic Linux distributions. What do they have in common? The concept of so-called atomicity. In other words, your system is this "untouchable" partition, outside of the (easy) grasp of the user, coincidentally the actual OWNER of the device. The system updates wholly, fully, swapping its old root with a new root during an update. As a user, you can only install userspace programs or apps, which you lease from online stores. The old concept of handling libraries and packages does not feature in this design.

On paper, this sounds interesting, because:

- You would have robust security.

- You can take advantage of new packaging formats - AppImage, Flatpak or snap.

- You can use online stores, and we know this seems to work well in the iOS and Android space.

- You gain traction and popularity and success.

On paper ...

Here we go again

I decided to write today's article because I'm seeing a recurrence of an old, familiar issue that's plagued the Linux desktop since its inception. The ACTUAL reason why Linux hasn't made it big.

Productization.

The Linux desktop isn't a product. Not even a collection of products. Even the most mature distros are projects at best, assembled haphazardly from a thousand disparate components, with little to no integration, or if there's one, it may be broken come a new low-QA update.

The problem of productization is not a technological one. Never was and never will be.

But the Linux people, time and time again, are trying to solve it with technology - because they are primarily software people who seem the world through the software prism. Insert Dave Chapelle's Old Solutions Require New Problems meme. Or something.

Why atomicity is the wrong thing at the wrong time, and then some

OK, let's talk about some real (technological) problems in the Linux world:

- Package management is tricky.

- Support for commercial software is tricky.

- Linux stores are barely adequate, and their security is ... so so.

- The Linux desktop is not a product.

Package management

Linux is heavily fragmented, with about at least active 300 distributions competing for the tiny 1% market. This is beyond any overkill in any sense. To make things worse, there are multiple software packaging formats, multiple software management tools, both CLI and GUI, multiple desktop environments, multiple everything. This makes Linux extremely hostile to productization, on a purely technological level. After all, if a company wants to target "Linux", what do they do?

The answer is, focus on the big names, and ignore everything else. This is why 99% of all Linux commercial software is packaged either for Red Hat (rpm) or Debian (deb), tested on Gnome, maybe KDE, and everything else is out of the picture. The same situation we had in the year 2000. Nothing has changed in 25 years. The proliferation of distributions did not help. Quite the opposite.

But you could say, what if we narrowed things down? Ah, you see, even in each of these sub-groups, there's tons of fragmentation! There are 50 Debian-based distros alone! Even if you take the big, most popular Debian-based one, Ubuntu, it, too, has tons of offspring. The Ubuntu family features some 7-8 official and community flavors, plus countless spins and forks. So, when a software company wants to target even a small portion of the Linux market, they still need to make further compromises. Hence, Debian = Ubuntu, and that's about it. In fact, due to Ubuntu's popularity, it's actually Ubuntu = deb.

Ah, so Ubuntu. But take Ubuntu version n and version n-1, and quite often, you won't be able to run any one piece of software without recompiling the code for the particular platform!

In comparison, take any which Windows exe file, and it will run on pretty much any version of Windows. I still have software from early 2000s running on Windows 10/11 without any modifications whatsoever. There's no such thing, not even remotely close, for the vast, vast majority of Linux software, free, paid, commercial or otherwise. The market just got smaller and even less lucrative. You're targeting 1% of the 1%, unless you're willing to recompile 43 times.

Package management, redux

This fragmentation has led to the birth of the likes of AppImage, Flatpak and snap. Security got into the equation retroactively, as it could be conveniently added into the model, but we shall discuss it a bit later. All right. So yes, now, instead of seventy formats, you only have three. Success.

Well, not really.

- Sure, the new formats do simplify distribution, to some extent. If you build a snap, then you have access to about 40 distributions, out of the box, versions notwithstanding. Sounds good. The problem is, the ecosystem isn't as robust as it sounds. For example, due to the massive architectural differences among distros, if you install the snap infrastructure on one or the other, you might not get the results you expect.

- AppImages may not run, sometimes due to libc, sometimes due to fuse. Technobabble for the common user.

- Flatpaks can work, but what's your source of truth? There are multiple Flatpak remotes.

- The coincidental addition of the security model (sandboxing) to snaps and Flatpaks has also introduced problems with theming, icons, file format association, and such. In other words, a software vendor may approach these new formats with enthusiasm, expecting them to provide uniform, consistent results across the entire supported base of distros. Alas, in reality, this is not the case. Since companies cannot rely on 100% fidelity and repeatability of results for their programs, they may choose not to use the new formats.

- The worst part is, the new formats are NOT compatible with the old ones. Of course. So if you want to use snaps or Flatpaks, you must ADD to your operating system. Instead of having just one package manager like zypper or apt, both the command-line utility and the equivalent GUI store, now you have two, maybe three competing software tools. This adds complexity and overhead.

- Now, distros become these hybrid animals, with even less quality and consistency than before.

And, still, there's no productization.

Then, there's the matter of trust (and security). More on this soon.

Support for commercial software

It's quite simple really. When a company sells its products, beyond pure profit, it wants its products to work well, reliably. Thus, they test for hardware and software compatibility. But what happens when:

- You cannot guarantee hardware?

- You cannot guarantee software?

- You cannot sell your product?

This is the Linux desktop. A company creates a product, and it tests it this or that way. Then, even if it manages to sell it, miraculously, for and on Linux, the company has no guarantee when or how their program will be used, and whether the underlying hardware will do the job, if the drivers are all cushty, and such.

And remember, even if ALL of the Linux desktop distributions miraculously united overnight, it's still a market of about 1% (or a bit more, recently). All things being equal, a sale in Linux translates to 99 sales on other desktops. But then, let's not forget all the different desktop environments, kernels, incompatible versions, problems with the new packaging formats, and so forth. But let's be generous. Let's briefly ignore the format issues.

A shop without windows ...

Lots of Linux distributions feature GUI software managers. They call them stores a-la Play Store, of course. But they are not stores, nor do they behave like any. First, you can buy stuff in the stores. Today, there isn't a single implementation of a Linux store that allows people to seamlessly purchase software. Most stores only offer zero-cost "free" applications and programs. If you're thinking Steam or similar, nope, there ain't no equivalent in the Linux space.

Thus, even if the packaging format approach helps some with reduced software distribution overhead, companies still have no real financial incentive to participate in the Linux desktop space, because they wouldn't be making any money, even if they can relatively easily "sell" their digital wares in the Linux "stores".

Online stores are supposed to give the user an "experience". I'm jaded, I hate the concept, but I understand that's how the common brain works. Fighting it is not going to change the world. If Linux distributions choose to "offer" their users graphical software managers or stores or whatever, then, they need to abide by the rules of the masses, and make these stores accessible to the ordinary human.

That doesn't mean extra trash like ads and such, but the shopping experience needs to be easy, simple, accessible. Without paid software, without the whole framework of convenience, the model deters ordinary users and provides no benefit to the seasoned geek. Only derision.

All of these are fundamental issues that have plagued the Linux desktop since day one.

The would-be solution? Alas, not what you expect, I'm afraid ...

Solution!!! The "Google" approach!

What annoys me beyond belief is the fact so many (younger) companies and their developers seem sooooo fixated on Google (and similar "newer" businesses) as the holy grail of success. They all see the modern-era giants as next-gen companies that have succeeded in the world of legacy giants, by offering a brand new, fresh approach to ... well, everything.

This is totally inaccurate, of course, but the belief is there.

And so, in the Linux world, in a rather unimaginative fashion, the nerds look at the big names and their tech stack, and assume that IF THEY COPY THE STACK THEY WILL ALSO COPY THE SUCCESS. Again, a total fallacy, proven a thousand times over in the past two decades, and yet, the nerds keep on insisting, as if the third or the seventh attempt at the same will yield miraculous results.

It's utterly, utterly simple:

- Google has created the Chromebook.

- It runs Chrome OS.

- It's a Linux-based operating system, under the hood.

- It has an "atomic" model. The system is read-only, and you can only touch applications. This makes it ideal for public spaces like libraries, kiosks or schools, where you can quickly and effectively restore the system base. This does not make for a good general desktop computing model, mind.

- The user interacts with the system using (Web) app, through the Google ecospace.

- Since Google has a powerful online store, boom, it's all there.

The big problem is, the Linux folks only see the end result. They don't ask WHY Google's model is so successful. And that's all that matters in this story, and why we're in yet another cycle of fragmentation.

Okay, why is Google so big?

It's quite simple. Luck, timing, lots and lots of investment, focus on the data. Google didn't go after hardware until it had a huge chunk of the digital market under its proverbial belt. It didn't attempt mobile until it was sure it could OFFER the users an ecospace of dopamine and brittle joy. It had MONEY to compensate for mistakes, money to buy out competition, money to do tons and tons of research and exploration.

Above all, we have survivorship bias. At any point in time, look at whatever 100 companies freshly out of IPO, VC incubators, startups, you name it, and project 10-15 years into the future, I guarantee you won't be able to tell which among the 100 will become the new giant. You don't know, and neither do professional investors who do this for a living. Google succeeded, and we're blind to the dozens if not thousands of Googlesque companies that no longer exist, and no one remembers anymore.

For that matter, even Google doesn't know what Google will do! Look at the graveyard of discontinued Google products. Just study something like Stadia and compare it to GeForce Now, for instance. What happens to Google Lens? Like any big company, it throws money at the wall, checks what sticks, it tries and tries endlessly, has the wallet to absorb it all when most things naturally fail. Evolution, pure and simple, digital style. What matters is that projects that do succeed eclipse all the failures.

Linux people seem to forget this critical detail. Indeed, let's go back to the Linux software ...

Not all Stores are made equal

To highlight why technology and software are 100% IRRELEVANT to success, here's a wee breakdown:

- Microsoft Windows rules the desktop. Microsoft failed in the mobile space time and time again.

- Microsoft Store for Windows is barely used, despite having the backing of a trillion-dollar giant.

- Linux barely has any traction in the desktop space, but it dominates the server world.

- At the same time, Android is Linux-based, and it's the most successful mobile operating system.

- Apple's operating systems are based on UNIX, and they have achieved moderate market share, but Apple has enormous market success, beyond the actual percentage of devices and systems out there.

If you look at what unifies all these different components, it's nothing. You have a mix of C, C++, C#, Java, different kernel architectures, different packaging formats, different compilers, different everything. Not one tool here is a guarantee of success. Software is 100% interchangeable. Whatever model you select, you may or may not make it big.

Linux stores, what Linux stores?

Tragically, even before Android or iOS or anyone else had stores, the Linux desktop had its own. These had all sorts of names and incarnations. Effectively, they were just graphical management tools for command-line utilities that allowed Linux systems to install software. Even so, they offered something that did not exist, not even in the Microsoft desktop world. You could type a name of a program in a search box, and you would install it from online archives or repositories of this or that distro. Quickly. Safely.

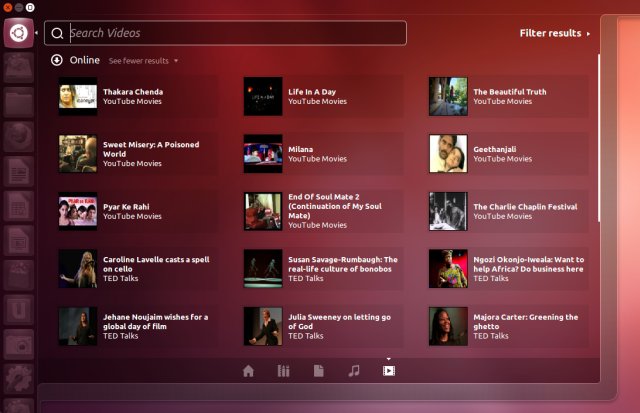

Then, Ubuntu came along and revolutionized the desktop. It allowed you to buy online content. Actually buy. You could stream videos and songs, buy software from its Store, everything that people take for granted today, Ubuntu did that more than a decade ago. You could open Ubuntu Software Center, search for free and paid software, even proprietary content, complete with screenshots and ratings and reviews. The screenshots below are from my happy and glowing review of Ubuntu 12.04 Precise Pangolin, released in 2012. Yes, 13 years ago.

The Linux desktop has regressed since. Yes, regressed!

- Today, there are no proper Linux stores. There are some, which we will discuss shortly, but they don't really offer any of the integration the old tool did. What we have today is the cheap copy of what Android/iOS are doing, minus all the things that make those stores so popular.

- Canonical has its Snap Store. It's not bad, and it's closer to a real commercial model than any other, but it still lacks a thousand things that ordinary people require. The non-Ubuntu distributions can make use of the community-led Flatpak stores, like Flathub. This one, too, lacks proper paid software support to be interesting.

- The "community" has community stores. In a typical Linux fashion, there isn't one. Flathub is the de facto Flatpak store. But then, until recently, Fedora had its own Fedora Flatpak store, which it preferred over Flathub. It may still be around, dunno. So if you were to search for a package, you could end up with two almost identical results, from two different online sources. Confusing, unnecessary.

- Community stores have no viable long-term commercial model. At the moment, they are backed up by sponsorship from various Linux-friendly entities. But if you're looking for a straightforward one-two hierarchy, there isn't one.

Let me explain in more detail:

- Canonical has somewhat curtailed its own growth by imposing certain restrictions on its own store. It seems to be trying to appease both the commercial world and the community world, but these two opposites cannot be easily reconciled. In other words, with the Snap Store being closed source, there's hesitation in the Linux community on relying on Canonical (vendor lock in). Also, the Snap Store "favors" the Ubuntu ecosystem. But then, it's an actual store with an actual company, a legal entity, behind it.

- The community stores, of which the Flathub is the chief and most popular one (but not the only one), are more open and easier to configure, but they also bring in lots of uncertainty into the mix. For an online store to be useful, it must be trusted. If it cannot be trusted, it's no different or better than going around the Web, randomly downloading software.

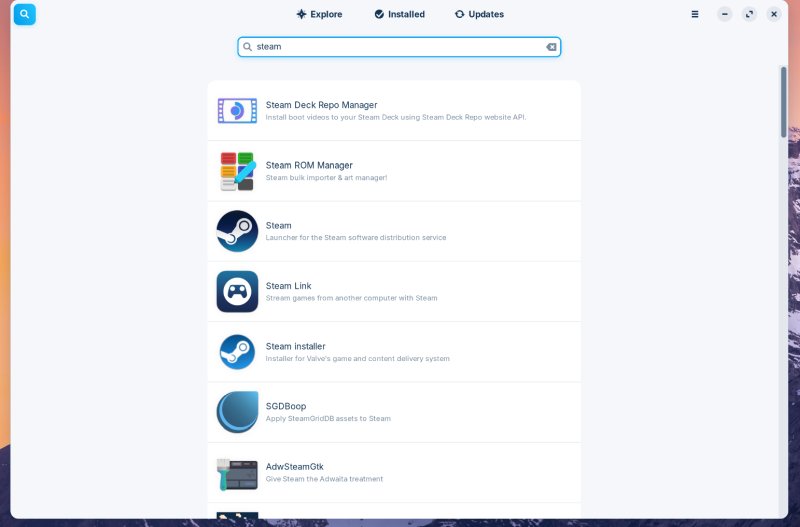

- As I've outlined in my openSUSE Tumbleweed review, my Fedora 41 Kinoite review, my Zorin OS 17.3 review, you could end up searching for various programs, the software frontends may serve various results, but these could actually be community-packaged bundles, not the official programs. In particular, in the Zorin review, a search for Steam returned two Steams, with the official one in the fifth place, and the unofficial one shown higher up, in the third place. Neither featured in the top spot as you'd expect, or as the only viable answer to a rather unambiguous query. Likewise, in my Wayland vs X11 benchmark article, toward the end, I showed you what happens when you search for Chrome. Even though Fedora 42 ships with the official Chrome repo, the software frontend does not show it all, and it instead offers the user a community-packaged wrapper for the browser from Flathub. To make things even worse, in another incident also quite recently, the Arch Linux AUR has been hit by malicious software, twice. In both cases, we're talking about unofficial browser packages. From a security perspective, this is 100x worse than distro archives. Atomic distros all aim toward stores, not archives.

- If you're an end user, you really have very little incentive using these stores, unless they shown only VERIFIED PACKAGES, made by their official vendors. Some software frontends allow you to configure this. Once you filter out the community contributions, you often end with a small selection of programs, all of which are cost-free, that is you can install them without any payment, because these Linux stores do not support payment processing the way say Play Store or Steam does.

- On the other hand, as an end user, you might as well continue using software from repository

archives, as they usually end up with some level of vetting (but this is no guarantee, either). You

can also manually configure packages. For example, grab Chrome from Google, grab Steam from Valve,

etc. This way, you have more control, and more security. More cumbersome, yes. But then, the

solutions are made for the nerds anyway, so why bother with unnecessary overhead?

All of these are paradoxes that Atomic distros don't solve. Quite the opposite:

- The Linux community dislikes the vendor lock in model, but the new atomic distributions heavily limit what the user can do! You have TPM, Secure Boot, read-only partitions, etc. All of these sounds draconian and you would expect them from Microsoft and their beloved Windows 11, not from "open" Linux. I know the concept of a system I cannot change makes me not want to use it. Simple.

- Special twist: lots of Linux distributions no longer build for 32-bit architecture. There's also been some utterly, utterly pointless talk about culling 32-bit libraries. Whenever I hear this argument, I realize just how user-unfriendly the Linux ecosystem is. HINT: Most games on Steam are 32-bit, as is the client itself. Removing support for the 32-bit stuff would effectively kill the Linux gaming world.

- The community-led stores have no "face" so to speak. Who do you "blame" if something goes wrong? This is why the Snap Store, despite its various deficiencies, is still the most reasonable choice, the same way the old Ubuntu Software Center was the most reasonable store choice 10-15 years ago.

- Atomic distros dispense with the DIY model. You are now at the "mercy" of your online store, probably a community store. But it's quite possible the software you need isn't there. You can no longer install a deb or rpm package, you must use the Flatpak (or the snap), but there's only an unverified package in place. What now?

- In many ways, going atomic means you lose freedom and gain ... well, nothing. You end up using a machine that is locked down like a Chromebook. And to what effect? What does this give you? All of the vendor lock in of Google and none of the benefits. Wunderbar.

On top of all that ... fragmentation!

To make things worse, the Linux community isn't working on ONE a-la Chromebook. Nope. Fedora has its own flavors, SUSE has its own, Canonical is working on its own, and more recently Gnome and KDE are developing their own. Don't forget the Wayland vs X11 self-destruction tragedy. Once again, like in the early 2000s, for every little disagreement, you have a forking in the road, and a whole new project starts, despite the fact it's 95% identical to the rest, and will be developed to only 80% completion.

AND NONE OF THESE ATOMIC DISTROS SOLVE THE CORE PROBLEMS OF THE LINUX DESKTOP!

- Paid software? Still not there.

- If a company wants to "put" its wares in a store, where do they go? Which of the dozen places do they choose?

- Without 100% tight hardware integration, atomic distros will be like classic distros, only harder to debug and will waste more bandwidth updating their overly large images. Again, it's the "young" approach, the frivolous assumption that everything can be done the "Google" way, or that disk space and bandwidth are cheap. Even if they are, there's no reason to do things badly.

- Without commercial backing, these atomic distros will merely be projects like all others before, usually abandoned after a while, when the developers get bored and move onto something else.

- There's no QA. The quality of the Linux desktop is meh. Not only done, the already poor QA will get even poorer, because instead of say focusing on the desktop environment or a handful of distros, the teams working on atomic systems will shift part of their effort there. It's slicing the cake even thinner.

- There's no documentation, or there's some, usually out of date by years.

- Product? Nope. There ain't.

Note: This image was taken from Wikimedia, licensed CC BY-SA 2.0.

In a way, each distro, each Linux enclave is a company, a company of 200-300 people where 280 people are missing. You ONLY have the software development department, and everyone is doing what they want, like it's the best college party. In some cases, there's 10 developers, in another there's 100, but even in the best case, the core team is tiny, highly vulnerable to changes, and there's still 10x more people missing, like accountants, artists, product managers, many other functions that are critical to making a complete product.

What you have is more software "games" for the sake of it, none of which, I repeat, none of which solve the core problem of productization.

- Making something look like a product does not make it a product.

- This is what software developers don't understand.

- This is why software developers must not be allowed to make products.

- Indeed, the only thing that unifies all Linux technologies is their un-product-driven, software-focused development, which is why the Linux desktop has never gained major market share.

Gloom and doom

It's not all completely lost. And you may say: Dedo, ordinary would actually prefer a simple no-frills desktop that they don't need to tinker with. Dedo, the vendors would be more likely to target Linux if there was a sane and tight baseline.

Exactly! But, that's the thing:

- Common people don't care about technological implementations of software. Indeed, those ought to be the LAST step in the process, but in the Linux world, they are always the FIRST step and often the ONLY step. The concept of "atomic" or whatever shouldn't be around until there's a clear definition of the product. And then, and only then should the best technology be selected. Not the other way around.

- What do you solve? How do atomic distros help? Do they make apps work better in Linux? Nope.

And this is where the story should start. Programs. How to make sure the common user can do what they want to do. At the moment, or rather, for the past 25 years, this has been the primary blocker for adopting Linux for mainstream users. Games and programs. Steam is making a revolution here, games wise. On the commercial side of things? There's little progress. The chicken and the egg problem.

Therefore, before there can be any distro that will make it big, there needs to be a complete set of programs. Free, paid, capable. In this regard, Gnome and KDE have more of a chance than other Linux entities, because they both maintain their own stack of programs. For the latter, I remember once counting about 170 programs and games. for instance, if all these can be made part of whatever the future ecosystem of a future KDE distro would look like, then awesome.

However, if you have a tiny repo with "just" the KDE software, for instance, you don't really need any fancy stores. Sure, for other software, of course, but if the idea is to have a tight, clean system, the tooling is all in the place already. There's no need to reinvent the platform. This brings us to the actual commercial software out there, which people use, mostly on Windows. It's not about finding the equivalent tooling - it's about using that very same tooling. This is what the Linux stack software cannot fix.

The apps will always remain the weakest link. The availability thereof, the quality thereof. The Linux desktop needs to be an ecosystem that people can use. Only then can it succeed, and the actual mechanism will not really matter. Microsoft never had a store until Windows 8. That didn't stop it. What it did have was the superb Win32 framework of programs, and backward compatibility. Grab you exe, and forget about it.

Microsoft has a Store now, and no one uses it. Why? Again, the modern apps nonsense. RT, UWP, whatever they're called, they are cumbersome to use and deploy, so why would anyone bother if you can have simple exe and msi files to do all your bidding? Why use a crappy store that wants you to sign in with your "online" account when you can go to whatever site, download the installer and move on?

The Linux people should learn from this example. If it's possible to create programs + store in one go, great. If not, there needs to be a foundation on how to accomplish that. The fragmentation is the enemy. Sure, it's partially solved by using Flatpaks and snaps, but then it will be again unsolved by having 50 atomic distros that each do things ever so slightly differently, uniquely, selfishly. Once more, the Linux world will become fragmented and not very lucrative. Throw in the hardware wrench, and there's no hope.

Money

The only way to break this vicious cycle is money. Companies that sell software have no desire to participate because Linux offers no commercial desktop model. No profit, no participation. This is THE PROBLEM. Until it's fixed, there won't be any redemption. Thus, the starting point is making a paid software store, which can sell everything and anything in every territory. At the moment, as an actual business entity, Canonical has the highest probability of success, should it embrace the opportunity. Gnome and KDE might also manage, if they play their cards right. Ideally, the Linux world would want to "help" Canonical succeed. Ah!

Regardless of how this gets done (if at all), without a seamless shopping experience, nothing will change. And even then, even once the tools are in place, the fragmentation will still remain the enemy. If there are too many stores, even if they all sell the same stuff, the companies may get wary, and choose to stay away. Look at the gaming space. There are tons of stores, all right. But ultimately, it's Steam first and foremost, and then a few others, all of which are orders of magnitude smaller and less influential. Technically, the entire gaming world has come down to one store that offers a full, seamless gaming experience. But it actually does that.

What we have in the Linux space is ... a competition (of egos) on who gets to have the BEST store. It's the same with distros, music players, office suites, etc. Even though there's no real commercial pressure as the vast majority of Linux tools are free, open source or both, everyone is still fighting as if they are the bittermost rivals, because they want to be the top dog.

Following a well-established tradition, it's not likely any distro will ever cede ground. Have you ever seen distros actually unite, combine forces? It's always fragmentation. So now, instead of fighting over the combo of kernel + package format + desktop environment, the fight will become atomic implementation + package format + desktop environment. Nothing changes.

Worse yet, years will be spent delivering new, buggy, unproven solutions that may one day reach maturity and stability, if ever. Meanwhile, the existing distros and tools will be neglected, just as Linux is starting to gain actual momentum. It will be brilliantly executed self-sabotage, subconsciously, of course.

Linux does not need atomicity. It needs quality. It needs more quality control and testing. Waaaaay more. It needs less development. Waaaaay less. There ought to be 10x fewer programmers and 10x more testers, including people from outside the tech world. There needs to be awesome documentation, and up-to-date documentation, but that's boring. It's easier to grab a new SDK and play with it.

Conclusion

There you go. An essay from your favorite curmudgeon. You think I'm wrong or old-fashioned or something. Now, scroll back up, and read my linked 2009 article on how to gain Linux market share. Yes, read that piece. See what I had to say 16 years back, and tell me I'm wrong. Or actually realize that the very stuff I had talked about back then is what needs to be done to get Linux moving in the right direction. Self-flattery aside, money is the secret sauce. The "magic" that made Google succeed, technology notwithstanding.

For Linux to get any sort of traction, it needs paid stores. Proper stores. Not community goodwill. Hard-cash stores. This sounds brutal, but it's the only thing that matters in the big world. If companies think they can make easy money, they will develop in ADA and FORTRAN for all they care. That sweet store is the entry point. The look and feel of the operating system is the last point. It's not too late to change direction. We've had atomic distros only for a few years now. We should stop before there are 300 of those. And trust me, no one needs another bucket of half-baked, for-developers, dark-themed systems that completely miss what an operating system ought to be. Along the way, there's no reason to antagonize nerds, either. At least for now, Linux actually gives them a controllable platform to do their nerdy stuff. They sure don't need another TPM-loving nonsense. They can have that from Microsoft, Google and Apple, today.

How will this be accomplished? Ah. Well, the deadlock needs to be broken. Someone needs to blink first. Someone needs to yield. Not likely to ever happen. In my view, the Snap Store is probably the best choice at the moment. By best, I mean the least bad, although all Linux stores and store lookalikes are light years away from being useful. Also, I cannot see a reality where the community concedes "defeat". Thus, unless some unforeseen miracle happens, things will stay the same for quite a while. Whatever happens, atomicity isn't the answer. It's merely a boring technical detail, not any better or worse than a dozen other implementations. But it will bring noise and instability into the Linux desktop, and dilute already diluted resources.

Just as Linux was starting to make some small sense, it's self-destruction, once again. Wayland, X11, new package formats, and now, we will have crippled half-functioning read-only systems added into the mix. Whatever happens, there must be no stability at any cost. The neverending tragedy called the Linux desktop.

Cheers.