Sign up for the daily CJR newsletter.

This piece was first published in French by Médianes, a media outlet, studio, and network dedicated to independent journalism in Europe. Translated and adapted by the Médianes team.

Media independence is no longer just a matter of editorial or financial autonomy—it’s also technological. As trust between major tech platforms and the press continues to erode, European newsrooms are starting to look differently at the tools they use every day.

X and Facebook, once seen as indispensable for audience reach, have largely turned away from news. Google, still the primary traffic driver for most publishers, keeps changing the rules of its search engine and now floods it with generative AI, threatening a source of visibility that remains vital for many outlets.

These shifts have led journalists to question not only their dependence on social platforms, but also the very foundations of their newsroom infrastructure: text editors, messaging apps, and data management systems. Behind those familiar tools lie very real dependencies: commercial logic, opaque rules, and political biases over which editors have no control. As some US tech executives publicly court Donald Trump in anticipation of political shifts, reliance on Californian tools feels increasingly risky. Many media organizations fear that their technology stack could become a Trojan horse, a subtle but powerful channel for outside influence and pressure.

Across Europe, such concerns are feeding into a broader movement for digital sovereignty, the idea that societies should retain control over the technologies that shape their public sphere. Some newsrooms have been acting on this principle for years.

Coherence down to the code

For Médor, an investigative magazine based in Belgium, technological independence has been a founding principle. “The question came up right away,” recalls Alexandre Leray, one of its cofounders. Launched nearly ten years ago as a cooperative of nineteen members, Médor was designed to represent the entire chain of magazine production within its founding team, from journalists and editors to designers and developers.

As a graphic designer, Leray helped shape a publication that would be deeply rooted in Belgian identity, from story topics to typography inspired by local heritage, and even the tools used to produce it. A member of Open Source Publishing, a Brussels-based collective founded in 2006 to promote the use of free and open-source software in design, Leray brought that philosophy straight into Médor. “How do you make a Belgian magazine using Californian software?” he asks.

Since then, Médor has made technological autonomy a cornerstone of its identity. The magazine announced it would leave Meta’s platforms (Facebook and Instagram) by the end of 2025, having already quit X. Internally, the team uses Nextcloud, a self-hosted open-source cloud system, as its main workspace. This decision even shapes the choice of file formats for compatibility reasons, encouraging open-source alternatives such as Etherpad instead of Google Docs for collaborative editing.

Technology in the service of sustainability

Across the border in France, the independent environmental-news outlet Reporterre has followed a similar path. Technological independence has been part of this French ecological outlet’s DNA since it was founded, in 2007. “Would you mind if we use Jitsi for the call?” asks Florent Triquet in an email before the interview, referring to an open-source video-conferencing tool. “When I arrived, some people still used Google Meet out of habit. We suggested Jitsi, and now almost everyone uses it,” says Triquet, the outlet’s Web developer.

That approach extends across Reporterre’s toolkit: no Google Docs, but CryptPad or Framadoc for collaborative work; no Word or PowerPoint, but LibreOffice; and a website built on SPIP, an open-source content management system originally developed by contributors to Le Monde diplomatique, a French monthly known for its critical, anti-globalization stance.

“These choices,” says Triquet, “are consistent with Reporterre’s values.” They also provide a measure of protection: “These tools can become instruments of coercion in the hands of states or corporations who might decide that Reporterre’s message bothers them a bit too much. From there, cutting off access to certain services could happen very quickly.” Those fears are not abstract. Recently, Microsoft deactivated the email account of the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court following sanctions by the Trump administration. For a newsroom dedicated to environmental issues, technological independence also ties into sustainability. Reporterre’s team mostly runs Linux, a lighter open-source operating system that extends the life of older computers, reducing e-waste and countering planned obsolescence.

Pragmatic sovereignty

At Contexte, a Paris- and Brussels-based media outlet specializing in European public policy and legislative news, the question of digital sovereignty has also become relevant. “We’re proudly Eurocentric,” says Clovis Picard, the outlet’s product and technical director. “It makes sense for us to be less dependent on US interests, especially given political developments there.” He acknowledges that a full transition to alternative tools “won’t happen overnight,” but the newsroom keeps these concerns in mind and evaluates tools on a case-by-case basis. “We’re not dogmatic, we’re pragmatic,” he says. “Do we want more sovereignty over our productivity tools? Probably, yes. But then we have to analyze at what cost.”

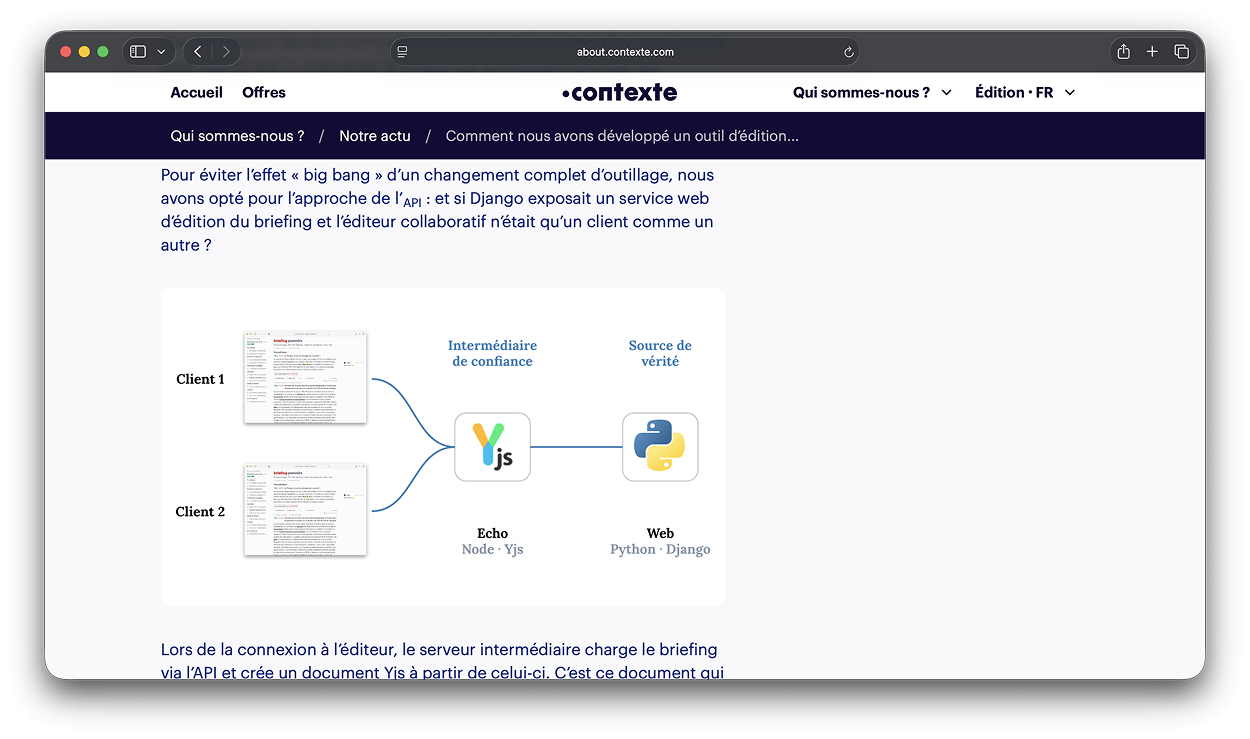

Beyond its newsroom operations, Contexte acts as a software publisher, having developed Scan, a legislative monitoring tool for its subscribers. In 2024, it launched Écho, an in-house collaborative editor that replaced Google Docs for its journalists.

The goal wasn’t necessarily to break free from Google, Picard explains, but to extend Contexte’s long-standing habit of internal development and technical control. Since its creation, the company has used Django, an open-source Web framework, instead of turnkey CMSes like Drupal or WordPress. A decade later, that culture endures. “For what’s most sensitive and most value-creating,” Picard says, “we want to control it as much as possible.” Every new hire receives training on Écho, product updates are presented to the newsroom, and all documentation is shared internally.

When design grows from technology

For Médor, creating its own tools is not only about independence, it’s also about aesthetics. “We realized that our tools would produce a different kind of graphic design,” Leray says. With both a print magazine and a website, Médor built a custom workflow that connects its Wagtail CMS (an open-source publishing platform based on Django) directly to its layout software, allowing content to be imported seamlessly from digital to print. This “Web to print” approach fosters a creative dialogue between digital and physical design, contributing to Médor’s distinctive visual identity and blurring the line between technology and editorial expression.

Learning, documenting, transmitting

Linux, LibreOffice, CryptPad—these names can sound intimidating to newcomers used to the comfort of Microsoft or Google ecosystems. But Triquet, of Reporterre, insists that even the most technophobic staff adapt quickly. “Some people now use terminal commands, something they’d never have imagined doing before,” he says with evident pride. This collective learning process helps journalists better understand their tools and take ownership of them. The same principle applies to freelancers and external collaborators, at least when possible. “If we join a project early enough, we push for open-source tools. If we arrive later, when switching becomes too complicated, we adapt,” Triquet says.

These technical choices raise the issue of transparency with audiences. At Contexte, Picard notes that while the outlet has “nothing to hide,” there hasn’t been much reader demand to know “how we build our newspaper.” For Médor, however, coherence is paramount. Financing companies that support political projects contrary to its values would feel hypocritical. “Readers who support us financially have a right to know their money is spent consistently,” Leray says. Leaving X or Instagram is visible to the public. Changing your office software is not. Yet these invisible shifts have tangible consequences for readers. For instance, the Médor uses Matomo instead of Google Analytics, an open-source alternative regarded as more respectful of user privacy and less intrusive. The choice is explicitly stated in its cookie banner.

Reporterre goes a step further, promoting digital literacy as part of its mission. “Media outlets have a role to play in educating people about ethical digital practices, the earlier the better,” Triquet says. When Reporterre left X, it published a guide encouraging readers to follow its RSS feeds, a decentralized, non-algorithmic way to stay informed.

Limits, but a clear vision

As coherent as these efforts may be, they remain exceptions in the media landscape. The few newsrooms exploring such changes often cite cost and complexity as major obstacles. “Migration costs are enormous. These are massive projects,” Picard says.

Contrary to popular belief, open-source is not synonymous with free. Médor recently announced that upgrading Odoo, one of its internal tools, came with a thirty-thousand-euro bill. At Reporterre, the team acknowledges both technical limitations and necessary compromises. They still use Slack for internal communication, and two newsroom computers still run Windows, one for administrative work, another for video editing, because some essential programs aren’t available on Linux. Médor likewise adapts when necessary. “We’ve worked with the same proofreader since our launch, and he uses a correction tool that only works with Microsoft Word,” Leray explains.

Writing scripts in CryptPad on a Linux laptop, only to post the final video on TikTok or Instagram—both owned by tech giants far from Europe’s ideals—might seem like a contradiction, even a futile effort. “We’re clearly in a gray zone,” Triquet admits. “We still use these platforms, but consciously, aware that they don’t reflect our values, while trying to move toward alternatives.” It is not resignation, but realism. Technological independence cannot be proclaimed. It has to be built, patiently, and over time.

Médianes, the studio, collaborated with Contexte in 2023 on its marketing and communications strategy.

Has America ever needed a media defender more than now? Help us by joining CJR today.