In November, I was privileged to deliver the inaugural Tamar Frankel Lecture at Boston University Law School. Professor Frankel is a trailblazer in corporate governance and fiduciary law, and it was wonderful to see that this lecture series has been established in her name.

Below is the text of my remarks on November 24:

Edit: Now there’s video – this is the Youtube link.

So, I want to begin by adding my voice to the chorus of praise for Professor Frankel’s work. She is a legend in this field, and I cannot tell you how honored I am to have been invited to kick off this series.

You know, the school advertised this lecture on LinkedIn, and her former students flooded the comments section with praise, a lot of which was words to the effect of, she somehow made securitization interesting!

Which is funny but for real, for those of us in the business space, it’s very much what we aspire to. What I will aspire to in this talk!

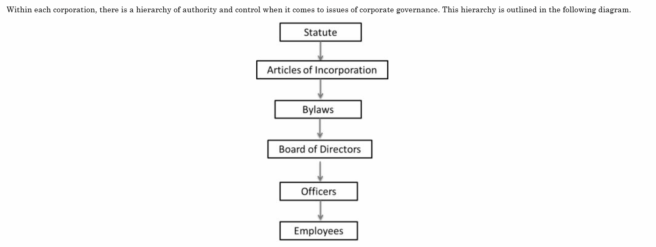

Which is called Corporate Governance Authoritarianism, and I’ll kick it off by pointing to this slide.

I’ve only got like two slides, by the way, so you’re going to be staring at this one for a while.

But this slide is a screenshot from the casebook I use in my introductory Business Associations class.

And I like to show it to students and ask them – what’s missing from this chart?

Shareholders! There are no shareholders on this chart. Which for me is actually an illustration of one of the fundamental problems in corporate law – where do the shareholders go? Where do they belong on the chart?

Why does this question matter?

I mean, we know why it matters if you’re a member of the board of directors.

We even know why it matters if you hold shares.

But most people aren’t on corporate boards, and in America, around 40% of adults don’t own stock – not even indirectly, like through a mutual fund.

So why does this question – where do the stockholders go? – matter to everyone, whether they’re a stockholder or not, whether they’re a board member or not?

Well, let’s think about a few corporations that are household names.

Facebook – now Meta, but I still call it Facebook – has 3 billion monthly users globally and is the primary source of internet access in many parts of the world.

Amazon Web Services powers 76 million websites, and not long ago, it experienced a brief outage that took down Venmo, Snapchat, Roblox, and – you’re welcome – Canvas at universities across America.

Walmart serves 255 million customers every week, and is the sole grocery store in many parts of the country.

My point is, in our society, corporations are major sources of power. Corporate managers – whoever sits at the top of the corporate pyramid – they will decide how billions or trillions of dollars of capital will be deployed across the globe. They will direct armies of labor provided by employees and contractors; their resources exceed those of many governments.

When corporate power is deployed in prosocial ways, we get fantastic innovations. We get the iPhone, and cures for Covid, and Reese’s Oreo cookies, and the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Investors earn enough for a comfortable retirement, employees are able to advance in their jobs, send their kids to school, buy their dream house.

But when that power is deployed in antisocial ways, well. We get cars that explode, or airplanes that fall out of the sky, or AI induced psychosis.

But critically, even the most prosocial corporations in the world will still leave some people better off than others, some people with more wealth than others, some people with more resources than others.

Ultimately, these decisions, who does well, and who does poorly, those are left to corporate managers.

Which means, everyone in our society is ultimately affected by those decisions. And so, the internal processes for making those decisions – they also affect everyone, whether or not they’re actually a shareholder and whether or not they’re actually a board member.

So that’s why it matters, how these decisions are made.

So how are these decisions made?

Well, to begin, when someone wants to create a corporation, they first have to seek a charter from a state. Any state, they can pick any state they want, even if they don’t have any operations there. That state’s law will then set the ground rules for how the board can exercise its authority.

Now, among the 50 states, there are variations, but one general rule is that, legally, corporations are run by their board of directors. Or – more typically in a public company – the board oversees corporate affairs on a high level, and then they hire corporate officers, like the Chief Executive Officer and the Chief Financial Officer – to run the company on a day to day basis. So, the board selects and oversees the top officers, and the top officers run the company.

To get the ball rolling, of course, they need investors, who contribute capital. Those are the shareholders, and their money is used to finance the company’s growth. To rent office space, buy equipment, hire employees. The shareholders can expect that if the company does well, they’ll receive a portion of the profits, which is why they invest in the first place.

The board and top officers are, collectively, the corporate managers, and they have relatively uncabined discretion to decide how to allocate the corporation’s resources. Whether to build or close a plant, or hire employees or lay them off, whether to pay profits out to investors or reinvest them in the firm. As a formal matter, when they make these choices, they have a duty to act in the best interests of the corporation and its stockholders – they have to act with care, and they have to act with loyalty. But as a practical matter, even if they make controversial decisions, money losing decisions, they are immune from any kind of legal liability.

That’s because of a principle known as the business judgment rule. For the vast majority of corporate decisions, even if they seem unethical, or short sighted, or incompetent, or stupid – the business judgment rule provides that courts will not second guess how the board chooses to run the company, and any shareholder lawsuit is doomed to fail.

For sure, I’m exaggerating – somewhat. There are going to be some constraints. At bare minimum, the corporation will be subject to various laws that mandate or prohibit certain conduct. And boards have to be concerned with profits, because if stock prices fall, at the very least, future shareholders will think twice about investing.

Still, corporate boards – a relatively small handful of people- maybe 10 or 12 in the largest companies, plus a few top officers – ultimately have an extraordinary amount of discretion to decide how other people’s money is going to be used, even when those decisions have global consequences.

But there is one natural source of constraint on board action – and that’s the shareholders themselves. Shareholders have almost no formal authority to interfere with board decisions; if there’s one universal truth in every state’s corporate law, it’s that the directors, not the shareholders, are tasked with running the company. And, due to the business judgment rule, shareholders cannot sue over board decisions that they dislike or that have bad outcomes.

But shareholders do get to vote on a very small number of corporate matters. And the most important thing they vote on is, the directors themselves. The board is elected by the shareholders in the first instance, and so, shareholders can replace directors who they feel are not performing their jobs adequately.

The power of that vote, though – the ability of shareholders to in fact make a difference through their voting power – has varied quite a bit over time.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries are when we first saw the rise of truly giant corporations, that dominated entire industries. Country-spanning companies headed by names like Rockefeller, Carnegie, and J Pierpont Morgan – the gilded age moguls who would later be derided as “princes of property” by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

And after World War I, mom and pop investors – ordinary people, the legal term is retail investors – poured money in public stocks. Shareholding quickly became widespread, in what has been described as a great shift of corporate finance from Wall Street to Main Street.

But at that time, a lot of the stock available to the public carried no votes at all. Voting shares were held by a small group of insiders.

And even when the general public held voting shares, corporate insiders were able to manipulate the votes through their power to collect proxies. Since it was infeasible for most shareholders to physically attend annual shareholder meetings – which might have been held clear across the country – shareholders voted by proxy, meaning, they’d fill out a ballot to be voted on their behalf by a designee at the shareholder meeting. Corporate managers were often in control of how proxies were distributed and collected, and used unscrupulous means to ensure that proxies were voted in their favor.

As a practical matter, then, mom and pop investors had very little say in the conduct of companies that depended on their capital.

The abysmal state of shareholder voting was viewed as a democratic affront, prompting outcry throughout the 1920s, until the system came to a thundering crash in 1929.

After the Crash and the Great Depression, dual class share systems – where corporations issued high vote shares to insiders, and low vote shares to everyone else – fell out of favor and were largely banned by the New York Stock Exchange.

Congress passed the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 which, among other things, gave the Securities and Exchange Commission the ability to regulate proxy voting. As one judge later put it, “It was the intent of Congress to require fair opportunity for the operation of corporate suffrage. The control of great corporations by a very few persons was the abuse at which Congress struck.”

But this didn’t exactly mean that shareholder power was now ascendant, because even with a norm of single class shares – so that every share carried the same number of votes – and even after curbing how insiders exploited the proxy voting system, ultimately, public shareholders were atomized. Each individual shareholder held only a small amount of stock, which made it difficult for them to organize and force management to address their concerns.

Some shareholders made the effort. In the 1930s and 1940s, a shareholder activist named Lewis Gilbert campaigned to expand shareholder rights. In the 50s, women shareholders organized to try to force companies to include women on their boards. In the 60s, Ralph Nader organized “Campaign GM” to persuade shareholders to vote for greater social responsibility at General Motors.

But these campaigns were largely unsuccessful. Boards viewed these corporate gadflies as annoyances, but not as real threats to their authority.

But matters did not rest there.

For many years, the largest corporations had been offering pension funds to their workers as part of their employment benefits. Traditionally, these funds invested only in bonds, or only in the stock of the company offering the plan. But in 1950, as part of a deal with the United Autoworkers, General Motors developed a new innovation: It would offer a pension plan that invested in a wide variety of corporate stocks, under professional management.

The notion caught on, and by 1974, pension plans held 30% of the stock in American companies. On top of that, in 1978, section 401(k) was added to the tax code. Section 401(k) encouraged employers to create retirement plans that invested a portion of employee salaries into diversified mutual funds.

The result was a de-retailization of the shareholder base, meaning, ordinary mom and pop investors stopped buying individual stocks and instead gained access to the market through giant institutional investors, pension funds and mutual funds, which themselves invest on behalf of their beneficiaries.

When the first federal securities law was adopted in 1933, institutions owned less than 9 percent of publicly traded stock. By 1980, institutions held 35% of publicly traded stock, and that number was rapidly increasing. The largest institutions held significant blocks of stock in multiple companies – 5%, 10% blocks – in some instances. By now, it’s about 70% institutional, by the way.

So these new shareholders – professionalized, wealthy, and concentrated – had pull with corporate management. Management had to listen to them. And the SEC encouraged shareholder oversight by requiring companies to disclose more information on director backgrounds and qualifications.

Now, then, in the 1980s, perhaps for the first time since the rise of the giant corporations at the turn of the century, shareholders held sufficiently concentrated power to pose a real challenge to corporate boards.

That power was most evident in the context of corporate takeovers. Buyout shops like KKR, Carlyle, and Blackstone would identify underperforming companies, buy up their shares, and take them over. Institutional shareholders endorsed these strategies, and so this period witnessed epic battles between incumbent management and corporate raiders.

Boards fought back by lobbying for legal protections. But, because federal law had only enhanced shareholder power, corporate boards turned to the states where their firms were incorporated. One by one, they persuaded state legislatures, and state courts, to give them fairly broad powers to block buyout shops from accumulating shares without board permission. That way, they could prevent acquirers from building up a control block and unilaterally voting them out.

So, dissident shareholders shifted tactics. Now limited in their ability to simply buy up a majority of shares, they instead would buy minority stakes – under 10% – and urge other shareholders to vote with them to install new directors. These activist attacks could be successful, again, because the investor base increasingly consisted of a relatively small number of large institutions under professional management, making it easier to gather shareholder support. The SEC helped matters along by revising its proxy rules again, this time to make it easier for shareholders to communicate with each other.

Additionally, the SEC adopted new rules that made clear institutional shareholders had a fiduciary obligation to vote their shares in their clients’ best interest, and they’d have to disclose the voting policies they adopted to meet that obligation.

Those amendments fueled the rise of proxy advisors – firms that specialize in advising institutional shareholders on how to vote the thousands of proxies they may receive every year. Proxy advisors help streamline the voting process for institutional shareholders, making it easier for them to consolidate around a single position. And, critically, they often recommend that shareholders vote against management. For example, they might recommend in favor of activists who are promoting their own director candidates, or against a deal that the board wants shareholders to approve. And – and this is the part that management really resents – they sometimes recommend that shareholders vote down proposed executive pay packages. Scholars have found that a proxy advisor recommendation this way or that way can shift up to 10% of the votes, so they have a real impact.

Now, not every dissident shareholder runs a contest to replace board members. Some shareholders seek to influence the board by sponsoring resolutions requesting board action on particular topics. Like, Resolved: The shareholders of Company X request that the Board do Y. That kind of thing.

These shareholder proposals can cover all kinds of topics – for example, they’re frequently used to reform corporate governance. Like, in companies where the Chief Executive Officer is also the Chair of the Board of directors, shareholders might ask to separate these roles.

But shareholder proposals are usually associated with attempts to make companies more socially responsible. For example, in 1951, shareholders sought a vote on whether Greyhound Bus Lines should desegregate the buses.

In the 1960s shareholders sought a vote on whether Dow Chemical should stop manufacturing napalm for use in the Vietnam War.

In 1992, shareholders sought a vote on whether Cracker Barrel should stop discriminating against gay employees.

But the difficulty with shareholder proposals, from a procedural point of view, is figuring out how to get them voted in the first place. Traditionally, a shareholder might attend the annual shareholder meeting, and then from the floor offer a resolution for all shareholders to vote on.

But today, as I said, everything is proxy voting. Meaning, shareholders are so dispersed, most don’t actually go to the shareholder meeting. Instead, they vote in advance by filling out a proxy ballot. By the time a shareholder meeting takes place, most of the votes have already been cast.

Which means, if a shareholder goes to the meeting with a new proposal to offer from the floor, it’s too late, most of their fellow shareholders aren’t attending the meeting in person and have already cast their ballots.

Well, the SEC knows about this problem, so way back in 1940, it began to require that corporations include shareholder proposals on those proxy ballots that are circulated in advance, so that all shareholders have a chance to vote on them.

But, even with those rules in place, for a very long time, these proposals were not very successful. Historically, they have garnered very low levels of support.

But once again, as the shareholder base consolidated, something shifted. Large asset managers began to support some proposals. They voted in favor of resolutions for more board diversity. They voted for boards to prepare for climate change. At Sturm Ruger, shareholders voted for the board to report on gun safety.

This relatively recent success may again, be traced to the concentrated power of an institutional shareholder base, newly encouraged by the SEC to focus on their fiduciary duties when voting their shares, and assisted by the recommendations of proxy advisors.

So shareholder proposals have become a significant way for shareholders to signal discontent to corporate boards, and pressure boards to change direction.

Notably, the various levers of shareholder power work in tandem. Most shareholder proposals are nonbinding; meaning, they usually request board action but don’t demand it, largely because – as I said, under state law – boards are in charge of running the company. Shareholders can’t really demand anything; they can only ask.

But if boards ignore a successful shareholder proposal, then in the next board election, the proxy advisor will step in, and maybe recommend that shareholders reject a particular director candidate.

In other words, the power of proxy advisors, coupled with the shareholder proposal mechanism, has given shareholders more practical control over board decisionmaking than might otherwise exist.

Now, one way a board might try to escape this kind of pressure – control the votes!

During the 80s, when boards first found themselves under attack, they pushed to lift the New York Stock Exchange’s ban on dual class share structures, so that they could create high voting shares that would be allocated to their allies. They didn’t succeed – entirely. The New York Stock Exchange did lift its ban on dual class shares, but the new rule across all exchanges became that companies could go public initially with dual class structures – high vote shares for insiders, low vote shares for the public – companies can now go public that way, but the rule became that they couldn’t switch to a dual class share structure once they were already publicly traded.

That didn’t help existing boards defend against contests for control in the 80s, so the matter lay dormant for a while until companies like Google and Facebook made their public debut with dual class shares, giving their founders outsized voting power within the company.

The justification was, these tech companies needed space to invest in long term research and development, and therefore needed to defend against activists who wanted to see immediate profits.

That kicked off a trend for tech companies, Silicon Valley companies, going public while retaining founder control. Not all of them, but a lot of them, like Palantir, like Snap, like Robinhood, like Coinbase.

Other companies might have a single class share structure, but go public with one or two large blockholders, who hold 40% of the stock and therefore also have the voting power to defeat challengers.

But even that, it turned out, didn’t insulate boards from shareholder challenge – largely because of Delaware.

Delaware, essentially for historical reasons, is the most popular state for incorporating public companies. And, as I said, under state corporate governance law – which is usually Delaware law – boards have nearly complete discretion to make decisions about how to run their companies.

Nearly complete. The big exception, especially in Delaware, comes when a board operates under a conflict of interest. When the board makes a decision that will enrich themselves, at the expense of the shareholders, at that point, if a shareholder sues, courts will apply special scrutiny to ensure the deal was entirely fair to shareholders.

Now, if the board isn’t completely conflicted – like, say, let’s say only one member has a conflict, the rest don’t – boards can avoid that kind of scrutiny by leaving it only to the unconflicted members to decide whether to make an investment or take a particular course of action. If an independent member of the board makes the call, so the conflicted member isn’t the final decisionmaker, Delaware will once again defer to board judgment.

But controlling shareholders are treated differently than ordinary board members. Controlling shareholder conflicts are also scrutinized closely by courts, if a shareholder sues.

But unlike with board conflicts, Delaware did not allow controlling shareholder conflicts to be cured by letting independent board members approve the transaction. Because even ostensibly independent board members may feel beholden to a controlling shareholder – someone who can decide unilaterally whether they keep their job.

The upshot being, situations involving controlling shareholder conflicts, unlike board level conflicts, were being closely policed by Delaware courts.

And over time, Delaware came to take a very broad view as to what counts as a conflict, meriting this special scrutiny.

For example, recently, Facebook got into trouble with the FTC for violating users’ privacy. The FTC wanted to fine Facebook, and also fine Mark Zuckerberg personally, over these privacy violations. And, apparently, Facebook ultimately agreed to pay the FTC a larger fine than originally proposed, on the condition that Mark Zuckerberg would be personally spared. In other words, shareholder money was used to pay off the FTC in order to protect the controlling shareholder, Mark Zuckerberg.

That was the kind of thing that a Delaware court said represented a conflict, that the public shareholders could sue over. That case settled, for $190 million.

And Delaware defined control broadly too – even minority shareholders with large holdings might be deemed controllers, which meant, their conflicted transactions would be overseen by the Delaware courts. For example, as you’ve probably heard, a Delaware court invalidated Elon Musk’s $56 billion pay package at Tesla. The court held that Elon Musk was a controlling shareholder even though he had only 20% of Tesla’s shares, because, along with his voting power, he also had a lot of personal influence over Tesla’s board.

The upshot was, all these companies sought to evade shareholder pressure by going public with controlling shareholders, or large blockholders – only to run smack into the Delaware judiciary, which kept upping the level of scrutiny they’d apply to business decisions that involved controlling shareholder conflicts.

Now, I don’t want to overstate – corporate boards have had, and continue to have, a terrific amount of power to control corporate resources. Most shareholder lawsuits continued to be unsuccessful.

But between the voting power of institutional shareholders, and the oversight of the Delaware courts, public company boards found themselves under more pressure, and required to meet more demands from conflicting sets of shareholders, than ever before.

That’s the path we’ve been on since the 80s. The solution we’ve come up with to the problem we’ve been grappling with since the late 19th century: What do we do about the enormous amount of economic power wielded by the very small handful of people who control these vast corporations.

The solution we settled on was – create giant shareholders, and empower them to push back on boards.

But.

If the story of the past 35 years has been increasing exercise of shareholder power, the story of the last two or three has been a rather dramatic swing in the opposite direction.

Because while all this was happening in the public markets – shareholders gradually gaining more power, and making more demands of boards – it was a completely different story in the private markets.

As I said, in response to the 1929 market crash, Congress created the federal securities laws. These laws were intended to ensure that if companies sought capital from a large number of investors – from the general public – they would be required to make various disclosures.

Beginning in the 1990s, Congress and the SEC became persuaded that when a company only sells stock to sophisticated investors – like these new wealthy institutions – there is no need for disclosure. These investors can bargain with corporate managers for the information they need.

So, the securities laws were changed to make it far easier for companies to raise enormous amounts of capital without ever going public.

Startups – once again, mainly in the tech industry – found that they could stay private indefinitely, raising all the money they needed from a handful of wealthy institutions. Which meant their only disclosure obligations were whatever these investors demanded – which it turns out, often wasn’t much – and that information could be kept confidential from the general public.

Without public trading and public disclosure, these firms removed themselves from the pressure of public markets entirely. Well-heeled investors competed for the opportunity to invest in “hot” startups, and founders discovered they could choose who’d they’d allow to invest. They’d choose their own investors.

That meant, of course, that investors who developed a reputation for being quarrelsome or interfering with management prerogatives would be iced out – not just of one private company, but from every private company, all private company opportunities across the board.

As a practical matter, then, company founders, and their early investor backers, exercised unchallenged authority over their firms, even as their companies grew larger and more important.

Think of companies like SpaceX, Anthropic, OpenAI, Polymarket – these companies are household names, they are incredibly important systemically, and they periodically raise billions of dollars of investment funding. But their shares aren’t traded; they contractually restrict how their shares can be sold and who they be sold to. Meaning, the corporate managers have absolutely no fear of activist attacks. No one’s going to buy their shares and agitate for change. They don’t have to worry about lawsuits in Delaware; none of their investors will risk getting a reputation for causing trouble.

Because they operate out of the public eye and without the oversight of the court system, these massive private companies were able to develop their own governance practices. Founders, and early investors, instead of just electing board members and letting boards run companies, would actually enter into contracts that gave different investors very specific rights. Like, an investor might be able to approve or reject a CEO candidate. Or approve or reject merger proposals, or proposals to expand the board of directors. With these shareholder agreements in place, as a practical matter, it would be founders and venture capital backers who would make critical decisions about how to run the company, not the board members elected by the shareholders.

Many of these private companies failed, of course, and quietly disappeared – but when they didn’t, they could be wildly successful.

And when these companies did, eventually, go public, they might have these shareholder agreements – contracts that gave specific insiders the right to control company decisions – regardless of what the board members wanted, regardless of how the public shareholders voted.

And honestly, the sense I get is, a certain mindset was created, in this private company space. A mindset that accountability only inhibits action. That building a successful firm means centralizing power in a singular founder, and that any procedures that inhibit that founder’s ability to act represent a drag on profit-seeking or – worse – a drag on that founder’s ability to effectuate his singular vision.

This community – the community of private investors, venture capital, private equity, Silicon Valley – they contributed a lot Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. And almost immediately after his election, the federal government began rewriting rules in ways that limit shareholder voice.

For example, right out of the gate the SEC issued new guidance concerning whether large institutional investors would be deemed “active” or “passive.”

It sounds technical but it’s actually very important.

Investors who take large stakes in companies are legally categorized as either active or passive. Active means you’ve invested for the purpose of influencing management, and if you’re active, you’re subject to a very onerous public disclosure regime.

The very largest investors, like mutual fund complexes that invest most of America’s 401(k) money, they depend on being categorized as passive, because they are so big that it would be nearly impossible to meet the disclosure requirements. They literally could not meet the reporting requirements applicable to active investors.

For a very long time, the SEC treated the ordinary exercise of shareholder rights – say, discussing executive pay with management, or discussing corporate social responsibility matters – as appropriate for passive investors. Meaning, the large mutual funds could engage with companies on these topics.

But in February of this year, after Trump took office, the SEC announced that even these kinds of engagements could transform a passive investor into an active one.

Tellingly, BlackRock and Vanguard immediately scaled back their meetings with corporate management – the latest figures show that their board engagements are down anywhere from 30 to 45%.

In other words, the largest investors in the world are beating a retreat from overseeing their portfolio companies.

But that’s not all.

The SEC has announced plans to limit how frequently public companies report their financial results. Ever since 1970, public companies have had to report on a quarterly basis. Now, it looks like it’s going to be semi-annually, every six months. Meaning, shareholders will get far fewer updates about corporate performance, and far fewer insights into the kinds of trends the company is experiencing and the actions being taken by boards. Which of course, limits shareholders’ ability to influence management decisions.

But that’s not all.

The Trump Administration has declared what I can only call an all out war on proxy advisors, the companies that provide research and guidance to help institutional investors decide how to vote.

Currently, two big companies – ISS and Glass Lewis – dominate the market for proxy advice, so the Federal Trade Commission is investigating them for antitrust violations. And – this was just announced last week – the Republican administration in Florida just filed a lawsuit against them for antitrust violations, and the Texas attorney general has an investigation under way.

Meanwhile, the Trump Administration is drafting executive orders that will limit how they can advise shareholders. And because both ISS and Glass Lewis happen to be owned by foreign parents – ISS is essentially owned by the German stock exchange, and Glass Lewis is owned by a Canadian firm – the administration is investigating whether they pose a threat to national security.

Let me say that again. The administration is investigating whether the Canadians pose a threat to national security.

But there’s more.

The SEC approved a new program at Exxon, which probably will become a model for other companies. Exxon was permitted to approach its retail investors – the maybe 25% of stockholders who are ordinary people – and ask them to preregister all of their proxy votes, every year, perpetually, to vote their shares with management.

Don’t get me wrong, retail investors can always drop out of the program if they like – they can sign up to automatically cast their votes with Exxon’s management, and then change their minds. But remember, historically, the problem with retail shareholders is, they tend not to pay attention to corporate votes at all. That’s why they’ve been so hard to organize, it’s why shareholder influence only became significant when retail investors began investing through vehicles like mutual funds. Exxon is betting that once retail shareholders opt-in to the program, they’ll never leave. So this way, Exxon’s board can bank a significant number of votes in advance that are guaranteed to always support them, no matter what challenges are mounted by other shareholders.

Retail investors who have other priorities – who maybe want to oppose management on issues like carbon emissions, or CEO pay – those investors won’t be able to bank votes. Only the ones who support Exxon’s board.

But there’s more.

One significant way that we enforce the disclosure requirements of the federal securities laws is through the securities class action. Shareholders can sue when a company issues false statements that ultimately result in shareholder losses. Class actions, which group all shareholder claims together, are a critical tool because securities fraud cases are very expensive to litigate. Just from an economic standpoint, they usually are only cost-effective to bring if you can consolidate all investor claims together.

The SEC recently announced that it would allow companies to require that any shareholder actions be brought in private arbitration, rather than a courtroom. And, these private arbitrations would have to be brought by investors individually. Which means, even if some small number of shareholders have losses worth litigating individually – that’s a big if! – their claims would be handled privately, the public would never know details of what was alleged or how the claims were resolved.

But it’s not clear that it’s legal for companies incorporated in Delaware to adopt these mandatory arbitration provisions, so Paul Atkins, the SEC Chair, recently urged a group of Delaware legislators to change their law.

And there’s still more –

Because Chair Atkins has also announced he’ll be limiting shareholders’ ability to offer shareholder proposals for inclusion on the corporate proxy. He’s already taken some administrative steps in this direction under SEC rules, and he simultaneously urged Delaware legislators, and Delaware courts, to bar shareholder proposals for Delaware firms.

What about Delaware by the way? Where is Delaware in all of this?

Well, remember those companies that went public with shareholder agreements, handing individual shareholders the right to overrule corporate boards and make governance decisions for the company?

A couple of years ago, a Delaware court held that they violated Delaware law. Because if there’s anything that Delaware law requires, it’s that boards, elected by shareholders, hold the ultimate authority in the company.

That decision angered a lot of venture capital and private equity firms, who rely on shareholder agreements, and they threatened to move their corporations to other states. Because remember, no one is required to incorporate in Delaware. You can choose any state you like.

The Delaware legislature responded within months by amending its corporate law to authorize the use of shareholder agreements to displace board governance.

But the protests continued. Corporate boards and controlling shareholders insisted that Delaware law had become too constraining. So, the Delaware legislature – in consultation with top Facebook executives – once again amended its law, this time to get rid of all those strict limits that the courts had placed on controlling shareholders.

In other words, the mechanisms that enabled the rise of the institutional investor as a counterweight to insider control of our largest avatars of economic power are unraveling.

So, that’s where we are. That’s where we seem to be going.

That said, I want to take a step back and think about the story I’ve just been telling.

I’m talking about challenges to corporate boards that are instigated by shareholders.

And notwithstanding things like shareholder proposals over gun safety, shareholders by and large care about money. That’s what they care about – earning a financial return.

Especially institutional shareholders, because most institutional shareholders have fiduciary obligations to maximize wealth for their natural person beneficiaries.

So if we’re worried about the kind of economic power that corporate boards wield, we may not exactly think it’s a great improvement to have massive profit-seeking institutional shareholders push for more influence.

Those takeovers in the 1980s? They usually resulted in a lot of worker layoffs, and a lot of corporate bankruptcies.

Those dissident shareholders who take small stakes and push to replace corporate boards? Usually, they advocate for cost savings that harm employees – like, reducing employer contributions to employee retirement plans and pension funds.

Increased shareholder influence may not exactly be the solution to corporate power that we’re looking for, is what I’m saying.

But what’s also true is that this system creates a kind of division of authority, a separation of powers, within corporate governance. Boards know they are being scrutinized and evaluated by others; they can’t act entirely according to their own impulses.

They have to make public disclosures explaining themselves to shareholders. And those disclosures aren’t just available to investors – now they’re available to the general public, reporters, activists, employees, regulators – all of these different actors are given more insight into corporate operations. And that public disclosure creates entry points that the general public can use to lobby for change.

Judicial decisions – the kind that might be reduced if securities claims are shunted into private arbitration, the kind that are reduced now that Delaware has loosened its standards for addressing controller conflicts – those also provide an obvious mechanism of public accountability. Courts articulate standards of conduct for boards, and impose penalties if they fail to meet them. And of course, the mere fact of a public trial, regardless of outcome, surfaces additional information about how boards operate that can then create a basis for public activism.

It also matters, I think, if we limit private enforcement rights, so that the law – like the federal securities laws – can only be enforced by state actors, like the SEC.

Because when only state actors have the right to sue over lawbreaking – well, state actors can be captured. They can choose to enforce the law only against their enemies, and let the violations of their friends skate by. The state can consolidate its own power by promising a lenient enforcement regime only for those who don’t offer any opposition. They can’t do that when private shareholders have powerful enforcement rights – the state can’t reward allies with leniency.

That said, at this particular moment, our legal systems seem to be shifting. The ethos across the board seems to be that powerful men should not be accountable to the public. That the public is not entitled to information about power is being exercised. That extraordinary men should be able to enact their vision without any kind of procedural constraint.

In 1910, speaking of the giant corporations of the era, Woodrow Wilson said that “Modern democratic society cannot afford to constitute its economic undertakings upon the monarchist or aristocratic principle.”

That may have been the sentiment at the end of the Gilded Age; it remains to be seen whether it still holds today.

Thank you, and I look forward to your comments.

And another thing. In this week’s Shareholder Primacy podcast, me and Mike Levin talk about recommended reading material for activists or the activist-curious. Here at Apple, here at Spotify, and here at YouTube.