Imagine the world as you know it. Now, add 10 million people who care about birds. Did your world just get a little brighter?

More from the Report

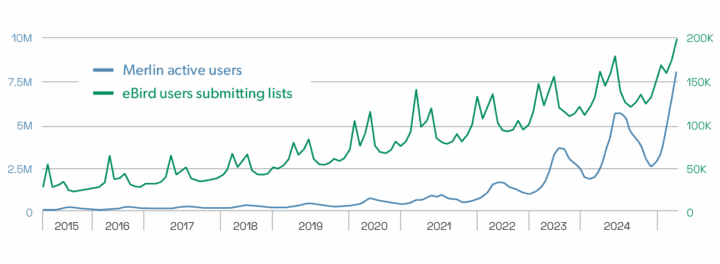

Ten million. It’s an astronomical number. And yet that is exactly what Merlin, the free bird ID app developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, has accomplished since launching in 2014. Ten million active users the world over, from experts in the field to neophytes who let the app run in the background during their morning routine—and they’re turning enthusiasm and newfound joy into participatory science that helps protect birds and biodiversity.

From Serbia: “It is my honor and pleasure that 165 of my photos were used to train Merlin to identify birds.”

From Costa Rica: “Great for beginners. It motivates you to keep expanding your life list.”

From India: “The app is so user-friendly…you can know about a lot of birds around you based on the pictures and their calls.”

From the U.S.: “My four-year-old daughter and I were using Merlin to identify about 12 birds in our backyard. My daughter said to me, Daddy, your phone is magical. I’ve been programming for over 40 years. Merlin amazes me too.”

So how is it that millions of people now hold this magic in their pockets? To satisfy that question, we have to go back nearly two decades when the Lab’s idea for a bird ID app first hatched.

An Origin Story That Almost Wasn’t

The year was 2008 and the Cornell Lab wanted to expand the capability of its online guide, All About Birds. According to Miyoko Chu, senior director of Science Communications at the Lab, users wanted more than the site could provide. “When we looked at analytics, we saw a lot of people typing in phrases like little brown bird. It became clear they were trying to use our website as a bird ID tool.”

When we looked at analytics, we saw a lot of people typing in phrases like little brown bird. It became clear they were trying to use our website as a bird ID tool.

Miyoko Chu

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Lab didn’t have capacity to reimagine All About Birds. These were the early days of broad-based artificial intelligence, so the team brainstormed a game of 20 questions that would utilize machine learning to produce a positive bird ID and proposed it to the National Science Foundation. “The heart of the proposal,” says Miyoko, “was the power of a bird’s name. If you see something and you don’t know its name, it’s really hard to learn more. But as soon as you can call it a Yellow Warbler, you’ve got all the information in the world at your fingertips.”

After winning the NSF grant, the team needed to figure out how to teach the machine-learning model how to identify birds. Jessie Barry, who now leads the Merlin program through the Lab’s Macaulay Library, cites AI as the reason the project was funded, but concedes that the initial machine-learning task didn’t work all that well. “We didn’t have enough data,” says Jessie. Meanwhile, the team discovered a faster solution: the power of eBird data.

In the early 2010s, eBird, the Lab’s worldwide bird observation platform, was taking off. Tens of thousands of birdwatchers had already contributed millions of sightings, and their observations added two crucial factors: time of year and location. This meant that instead of trying to guess among, say, 800 species, eBird could help narrow it down to the few dozen species a person would most likely see. With just three more questions, it presented an answer. With time and location in hand, the team was able to compress the initial 20 questions into a simple five-question rubric to identify birds.

Halfway through development, the team met another “grant”—Grant Van Horn, an undergrad at UCSD knocking on doors and looking for professors to work with. He had joined Caltech’s Visipedia project aimed at training computers to recognize objects in photos, using machine learning. To source the photos, they looked to Flickr, the world’s largest photo-sharing site at the time. According to Grant, “Flickr’s top photos of the day were some landscapes, a few portraits of people, and, inevitably, birds.”

The question quickly became: Can we train a computer to recognize all these bird photos?

“The Visipedia team had scraped the web to build this dataset,” says Jessie, “but many of the birds were misidentified.” In a spirit of sharing and collaboration, the teams partnered to build a robust and accurate archive of images. As Jessie remembers it, “We approached a bunch of friends to get their photos off Flickr as a way to build the dataset.” By 2010, they’d collected enough images to have a basic working model. According to Jessie, “We were thinking, okay, 25% of the time, maybe this pre-Merlin system could identify a bird accurately.”

Another breakthrough came when the team realized they could build out Macaulay’s image archive by enabling eBirders to upload photos directly into the Macaulay Library as a part of their checklists. It has become a virtuous cycle; as birders share more images, the results get more accurate. Today, Macaulay’s archive is an asset that simply can’t be replicated anywhere else. On average, eBird users contribute an image every two seconds, and the accuracy of Merlin’s visual ID hovers around 98%.

“By the way,” Miyoko adds, “this was almost not funded. Some of the NSF reviewers were quite skeptical, asking, How is this teaching anyone? It’s basically doing all the work for people, you’re just giving them the answer.”

What impact would this new app have on the world of birding? Or, for that matter, on how people learn?

Launch

Where did the name Merlin come from? Miyoko remembers flipping through names of birds and coming to rest on the Merlin, a falcon that is both small and fierce. Merlin populations declined in the 20th century due to DDT and other pesticides, but bounced back once those were banned. Of course, Merlin also refers to the mythical sorcerer in King Arthur’s court. “We’d always talked about it being this magical experience where you would be so surprised that this name could pop up and give you the answer you were looking for,” says Miyoko. The team rallied around the name and began making final preparations for the app’s release.

On average, eBird users contribute an image every two seconds, and the accuracy of Merlin’s visual ID hovers around 98%.

With the NSF grant nearing its end, a fork in the road came when it was time to decide what to charge for Merlin. Alex Chang, who was leading the team’s web communications, says, “At that time, companies were selling their apps for $1, and it was moving toward $2.” But the Lab wanted to build a community, not just revenue. So Alex, who was also pursuing an MBA at Cornell at the time, wrote a business case showing that it was more valuable to offer Merlin for free in exchange for an email address.

That decision led to far more downloads, including in countries where any fee might be a significant barrier. It also gave the Lab a channel to connect with its users. Today, Merlin is at the heart of rapid growth in the number of participants and supporters of Lab programs, which has helped transform the scale of the Lab’s global conservation work. Merlin has become the Lab’s front door.

The app launched in 2014 with the ability to ID 285 species—just the most common backyard birds in North America—using the five-question rubric Jessie’s team developed (the photo ID capabilities launched two years later). In 2015, Drew Weber joined the team to broaden Merlin’s geographic footprint. Drew is now the project manager on the Merlin team, and has helped expand Merlin to include 11,000 species, nearly every known bird in the world. When he comes through customs after an international birding trip, the agents get excited when he tells them what he does for a living. “We love Merlin,” they say.

“Merlin is a wide funnel that brings people into the world of birds,” Drew says. “Some of those folks are going to download eBird and start collecting data. Some of them are going to start caring about birds and give money to protect their habitats. But for many others, Merlin simply lets them start to recognize and enjoy the birds around them in a way that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.”

Susan Fox Rogers, author of Learning the Birds, agrees. “Merlin changed everything. This is something to celebrate in every possible way.” Susan started birding at age 49. “When I first went out, I couldn’t do it by myself. I needed the John Burroughs club, I needed to get to a baseline. It took two or three years, maybe 20 trips.” It used to be that to become an expert, you had to learn from another expert. But for millions of learners of all ages, Merlin has become their mentor.

But there was another quest on the horizon—one for the “holy grail,” as the Lab’s former executive director John W. Fitzpatrick puts it. For decades, the Lab had been trying to crack tech’s ability to identify birds by sound. Could Merlin become the “Shazam for birds”?

The Tipping Point: Sound ID

In many ways, it’s an unfair comparison: Shazam is an app trained to recognize the one true signature of a pop song in the swirl of a crowded room. Birds are different. They have more than one call. Songs differ slightly each time they’re sung. And even members of the same species can develop distinct dialects region to region. Add to that the sound of wind. Traffic. Your shoes crunching the forest floor. Or what about sound dampeners, like buildings and trees? Not to mention the songs of other birds.

If we get to the point where one in 20 people in the U.S. is engaged with birds when a local land trust reaches out, they’re going to be more ready to hear those messages.

As Jessie Barry remembers it, “When the pandemic hit in 2020, we saw [the number of] Merlin users go through the roof. So many people were watching birds, sometimes for the first time. It was a dream come true: The world is paying attention to birds. What can we do with this opportunity?”

While attending an audio workshop in New York City with Jessie, Grant Van Horn was inspired by presentations that included spectrograms. “What struck me,” says Grant, “was that we were looking at photos of audio. I thought, Wait, they just take their audio and make a picture? I’m a computer vision researcher, I can absolutely work with that!”

The timing was right: eBird had just begun accepting audio uploads in 2015. That meant Grant had five years’ worth of recordings to experiment with. “Someone told me Merlin’s photo ID couldn’t distinguish between the Alder and the Willow Flycatchers. I wasn’t really a birder before all this, so I asked my colleagues how you’d tell them apart in real life and they told me they’d listen to the vocalizations.”

So like the presenters at the audio conference, Grant made pictures. Specifically, he took 30 audio clips apiece for both flycatcher species and rendered spectrograms. Just as he’d trained Merlin’s algorithms to recognize images of birds, Grant now used the same technology to recognize images of their sounds. “The computer was perfect. It’s like, 100% accuracy.”

To make Sound ID feel miraculous, Merlin needs to bank at least 100 clean recordings of every call for each species. To achieve this, around 350 experts annotate thousands upon thousands of spectrograms made from recordings submitted by people from all over the world. These annotators painstakingly draw and label boxes around individual calls in the spectrograms, helping to train and improve Merlin.

Jessie was anxious to get this capability into the hands of people while birds still held their attention, so Sound ID was launched in June 2021. According to Drew Weber, “Each spring, we see a massive uptake. That year we had a double bump in downloads: May for migration and June for Sound ID.”

“When we first started,” says Alex Chang, “we got to number four in the app store’s reference category, and we thought, There’s no way we can beat the Bible, right? Like, how do you beat the Bible? But I guess Sound ID was the answer to that, because we got to number one.”

“Sound ID put Merlin on the map,” says Drew. “It’s in the mainstream conversation now. Sarah Jessica Parker posted about it on Instagram. Sam Darnold, the Seattle Seahawks quarterback, has talked about it at press conferences. Sound ID was a game changer.”

Tuning In at Scale

Imagine the world as you know it. Now, add 100 million people who care about birds. Add one billion. These numbers may seem improbable, but Merlin’s growth continues to accelerate. This past spring, American usage of Merlin was up 40% over last year. Europe was up 70% over the same period, and there’s double-digit growth in Africa and Asia as well.

“We have a long runway on these projects,” says Jessie Barry. “We’re building out Sound ID in South America, in Africa, really building a global team. We try to look a few years down the road for new opportunities, but right now we’re seeing big returns on the Lab’s mission—connecting people to birds is squarely what Merlin is able to do.”

How has this marriage of science and tech captivated so many people? “I think you can go all the way back to Arthur Allen and Peter Paul Kellogg,” Jessie continues. “Arthur Allen founded the Lab. Peter Paul Kellogg was an electrical engineer. Together they figured out how to record the first bird sounds in North America in 1929. So in some way, that combination of engineering and ornithology that built Merlin goes back to the Lab’s origin story.”

In Silent Spring, Rachel Carson’s landmark book about the environmental destruction caused by DDT and other pesticides, she pointed to the “silencing of birds.” What if spring comes and no birds sing? Of course, this formulation only works if people are listening.

With Merlin, more than 10 million people are tuning into the world around them. “I think we’re just starting to feel the scale of a community,” says Jessie. “If we get to the point where one in 20 people in the U.S. is engaged with birds when, say, a local land trust reaches out, they’re going to be more ready to hear those messages.”

Already there are signs that the next generation of birders is more conservation-minded. Less focused on personal lists, today’s birders see birds as neighbors. They’re asking questions about what birds need to thrive and what they can do to help. Susan Fox Rogers puts it this way: “If more people are using Merlin, then more people are thinking about birds. You can’t protect something unless you know it. You can’t love something unless you know it.”

Top banner photo credits: Tiktok photos courtesy @theylovefrioo, @nonbinarying, @badgerlandbirding. Additional photos by Gerrit Vyn, Ian Davies, Rachel Philipson. Lilac-breasted Roller by Andrew Spencer / Macaulay Library, Common Yellowthroat by Brad Imhoff / Macaulay Library. Back to top.