Are Fund Managers Asleep at the Wheel?

Introduction

In 2015, As You Sow embarked on a mission to identify and report on the most overpaid CEOs of the S&P 500 and whether or not pension funds and financial managers held companies accountable for such excessive compensation. At the time, we found that far too many funds and managers were rubber stamps for these excesses.

This 2019 study is the fifth report of our research results. During these five years, what has changed? Quite a bit, and not enough. Significantly, more large shareholders are voting against more CEO pay packages. Those who are not are more isolated and defensive.

Companies have responded to this shareholder opposition. A February 2019 Equilar analysis, Companies Shift CEO Pay Mix Following Multiple Say on Pay Failures, found that “The average CEO total compensation at companies that failed Say on Pay (shareholder votes) decreased significantly from 2011 to 2017, a total of 44.9% over that time frame.”1

Yet overall CEO pay continues to increase. According to Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) the average pay for a CEO in the S&P 500 grew from $11.5 million in 2013 to $13.6 million in 2017. An analysis by the Economic Policy Institute, which includes the cashing in of stock options, found that “in 2017 the average CEO of the 350 largest firms in the U.S. received $18.9 million in compensation, a 17.6 percent increase over 2016.”2

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which became effective in 2018, has been called a giveaway to corporations, which used their huge tax savings to buy back their own stock instead of creating more jobs or raising worker pay ($4,000 a year was promised), as supporters claimed would happen. However, the law produced a positive change with respect to executive compensation. It eliminated the loophole for executive “performance-based pay” in section 162m of the tax code that was used to get around the $1 million cap on the amount of executive compensation that corporations could deduct from their taxes. Many experts believe this “performance pay” loophole from 1990s tax legislation was a factor in the spiraling increase of CEO pay that followed.

Thanks to the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial reform bill, shareholders gained access to new information this year. Companies must now disclose the ratio of pay between the CEO and the company’s median employee, shining a brighter light on how high CEO pay has become. This new information can also be used in other ways. As discussed in the pay ratio section of this report, the city of Portland, Oregon was the first to introduce a corporation tax rate based on this ratio.

This change happened amidst growing acceptance that there are financial reasons to be concerned about economic inequality. In October 2018, the UN Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) published a critical report, “Why and how investors can respond to income inequality.” In the foreword, UN PRI CEO Fiona Reynolds writes: “Institutional investors have increasingly begun to realize that inequality has the potential to negatively impact institutional investors’ portfolios, increase financial and social system level instability; lower output and slow economic growth; and contribute to the rise of nationalistic populism and tendencies toward isolationism and protectionism.”3

As Bloomberg columnist Nir Kaissar noted in a recent editorial, “As the grim pay disclosures pile up year after year, the backlash against the corporate elite will intensify. If corporate boards can’t find a better balance in their pay structure, outside forces will, and at a potentially far greater cost to companies and their shareholders.” Bloomberg’s Alicia Ritcey and Jenn Zhao compiled the CEO-to-worker compensation ratios for companies in the Russell 1000 Index and found that “the median employee compensation for 104 of the companies is below the federal poverty level of $25,750 for a family of four. That’s the number below which workers are eligible for government assistance.”4

Opposition to high CEO pay has risen, and more companies have seen their CEO pay packages receive less and less support from their shareholders. European funds and U.S. public pension funds have made their opposition to a broken system clear. In this year’s report we pay special attention to those funds with the greatest change in voting practices on the issue of CEO pay as well as highlight some of the reasons that have led to more shareholder votes against those pay packages.

Methodology

HIP Investor regression we’ve used every year that computes excess CEO pay assuming such pay is related to total shareholder return (TSR). The second ranking identified the companies where the most shares were voted against the CEO pay package. These two rankings were weighted 2:1, with the regression analysis being the majority. We then excluded those CEOs whose total disclosed compensation (TDC) was in the lowest third of all the S&P 500 CEO pay packages. The full list of the 100 most overpaid CEOs using this methodology is found in Appendix A. The regression analysis of predicted and excess pay performed by HIP Investor is found in Appendix C, and its methodology is more fully explained there.

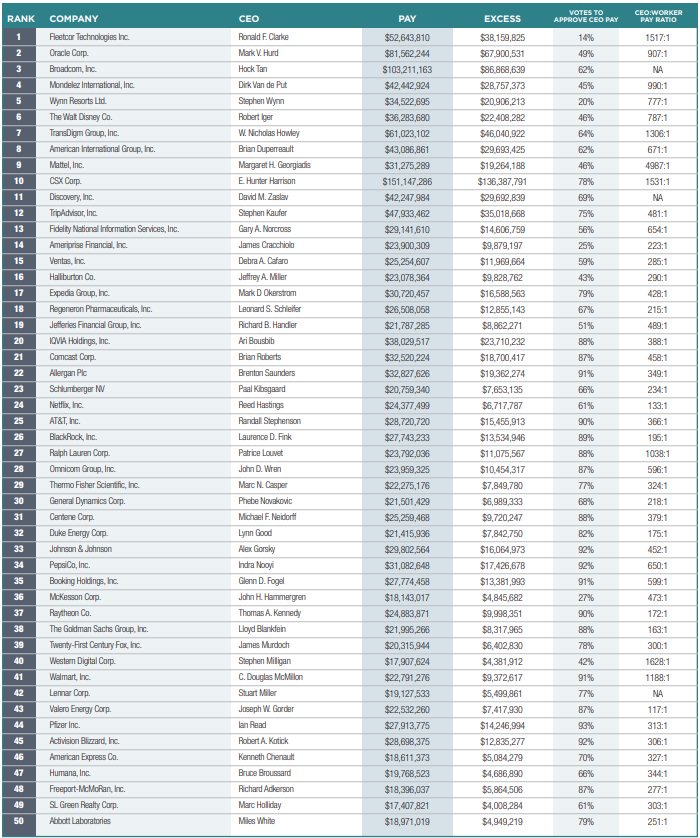

Figure 1 (below) lists the 25 most overpaid CEOs, identifying the company, the CEO and his pay as reported at the annual shareholder meeting, and the pay of the company’s median employee. Two companies – Comcast and Oracle – have now placed in the top 25 every year. Four companies – Discovery Communications, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Walt Disney, and Wynn Resorts – have each appeared the list this year for the second year in a row.

Highlight the titles in any column to sort numerically or alphabetically.

Rank |

Company Name |

CEO |

CEO Pay |

Median employee pay |

Pay Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Fleetcor Technologies Inc | Ronald F. Clarke | $52,643,810 | $34,700 |

1517 |

2 |

Oracle Corp.* | Mark V. Hurd/Safra Catz | $81,562,244 | $89,887 |

907 |

3 |

Broadcom, Inc. | Hock Tan | $103,211,163 | NA |

NA |

4 |

Mondelez International, Inc. | Dirk Van de Put | $42,442,924 | $42,893 |

990 |

5 |

Wynn Resorts Ltd. | Stephen Wynn | $34,522,695 | $44,437 |

777 |

6 |

The Walt Disney Co.* | Robert Iger | $36,283,680 | $46,127 |

787 |

7 |

TransDigm Group, Inc.* | W. Nicholas Howley | $61,023,102 | $46,742 |

1306 |

8 |

American International Group, Inc. | Brian Duperreault | $43,086,861 | $64,186 |

671 |

9 |

Mattel, Inc. | Margaret H. Georgiadis | $31,275,289 | $6,271 |

4987 |

10 |

CSX Corp. | E. Hunter Harrison | $151,147,286 | $98,697 |

1531 |

11 |

Discovery, Inc.* | David M. Zaslav | $42,247,984 | $80,858 |

522 |

12 |

TripAdvisor, Inc. | Stephen Kaufer | $47,933,462 | $99,643 |

481 |

13 |

Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. | Gary A. Norcross | $29,141,610 | $44,556 |

654 |

14 |

Ameriprise Financial, Inc. | James Cracchiolo | $23,900,309 | $107,082 |

223 |

15 |

Ventas, Inc. | Debra A. Cafaro | $25,254,607 | $88,630 |

285 |

16 |

Halliburton Co. | Jeffrey A. Miller | $23,078,364 | $79,636 |

290 |

17 |

Expedia Group, Inc. | Mark D Okerstrom | $30,720,457 | $71,696 |

428 |

18 |

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Leonard S. Schleifer | $26,508,058 | $123,418 |

215 |

19 |

Jefferies Financial Group, Inc. | Richard B. Handler | $21,787,285 | $44,584 |

489 |

20 |

IQVIA Holdings, Inc. | Ari Bousbib | $38,029,517 | $97,997 |

388 |

21 |

Comcast Corp. | Brian Roberts | $32,520,224 | $71,006 |

458 |

22 |

Allergan Plc | Brenton Saunders | $32,827,626 | $94,064 |

349 |

23 |

Schlumberger NV | Paal Kibsgaard | $20,759,340 | $88,604 |

234 |

24 |

Netflix, Inc. | Reed Hastings | $24,377,499 | $183,304 |

133 |

25 |

AT&T, Inc. | Randall Stephenson | $28,720,720 | $78,437 |

366 |

Policies and Explanations for Votes Against CEO Pay Packages

The most common reason cited to vote against pay packages is that they are not strongly connected to performance, but disclosure failures and other issues also factor heavily. Here is some specific language — collected from guidelines or disclosure on particular votes — that illustrates reasons for opposition. (Further information on sources available upon request.) All of these are explanations for why a fund may, or may already have, voted against pay packages.

Pay disconnected from performance; excessive potential pay; peer issues. Funds have policies that vote against:

CEO pay plans that have no absolute limit on the amount of some or all of various bonus payments;

CEO pay plans that have discretionary payments;

Some or all of CEO pay awards vest automatically as time passes instead requiring the meeting of some performance requirement at each vesting point;

Any performance requirement that allows vesting when performance is below the median of peers;

Any payment in the form of stock options.

Failure of adequate disclosure:

The short-term incentive program or long-term incentive program thresholds and maximums are not sufficiently disclosed;

No identifiable limit for each of the different components within the policy.

Insufficient long-term emphasis and risk mitigation practices:

Long-term incentive plans with performance cycles shorter than 3 years;

The absence of clawbacks of variable remuneration;

Insufficient holding period requirements.

Key Findings

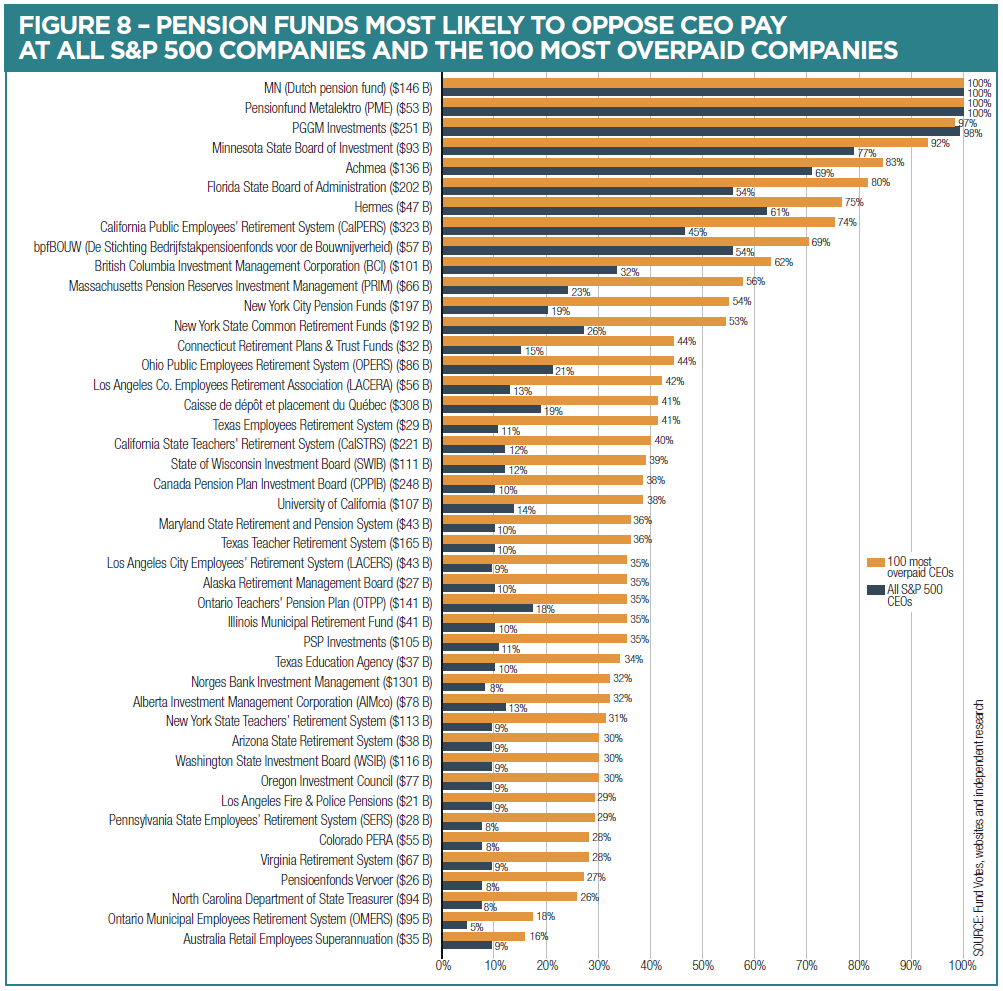

As in prior years, we note that pension funds give CEO pay packages more scrutiny and a greater level of opposition than financial manager controlled funds. Also, in general, European based investment funds vote against CEO pay packages at a greater rate than U.S. based ones.

Over the past five years the number of funds that have markedly increased their level of opposition to S&P 500 CEO pay packages has grown.

Several funds, with assets of over $100 billion each have more than doubled the number of CEO pay packages they vote against. The largest U.S. pension fund, California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS, with assets of over $350B) has increased the number of S&P 500 CEO pay packages that it voted against by a factor of almost eight. In 2013 CalPERS opposed only 6.4 percent of S&P 500 CEO pay packages, last year CalPERS opposed 45 percent of them. Figure 2, based on Proxy Insight data, shows funds with AUM over $90 billion in assets that voted against more than forty percent of the S&P 500 CEO pay packages. If the threshold of AUM of $1 billion is used, there were 87 funds that met the same criteria.

The number of S&P 500 companies where large numbers of shares were voted against the CEO pay package has increased.

While in the aggregate CEO pay packages still receive a large number of positive shareholder votes, that number is declining. In 2018 it declined to 90.4 percent—the lowest level since 2012. In 11 S&P 500 companies the number of positive votes was below 50 percent; in 35 S&P 500 companies, it was below 70 percent. Companies that received overwhelming shareholder opposition to the pay package of their CEO include Fleetcor Technologies, Wynn Resorts Ltd., Ameriprise Financial, and McKesson.

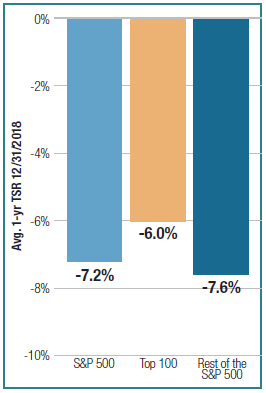

The companies with overpaid CEOs we identified in our first report have markedly underperformed the S&P 500.

Two years ago, we analyzed how these firms’ stock price performed since we originally identified their CEOs as overpaid. We found then that the 10 companies we identified as having the most overpaid CEOs, in aggregate, underperformed the S&P 500 index by an incredible 10.5 percentage points and actually destroyed shareholder value, with a negative 5.7 percent financial return. The trend continues to hold true as we measure performance to year-end 2018. Last year, these 10 firms again, in aggregate, dramatically underperformed the S&P 500 index, this time by an embarrassing 15.6 percentage points. In analyzing almost 4 years of returns for these 10 companies we find that they lag the S&P 500 by 14.3 percentage points, posting an overall loss in value of over 11 percent.

* First date w voting avilable 2014 **First data w voting available 2015 *** First data w voting available 2016

Two years ago, we analyzed how these firms’ stock price performed since we originally identified their CEOs as overpaid. We found then that the 10 companies we identified as having the most overpaid CEOs, in aggregate, underperformed the S&P 500 index by an incredible 10.5 percentage points and actually destroyed shareholder value, with a negative 5.7 percent financial return. The trend continues to hold true as we measure performance to year-end 2018. Last year, these 10 firms again, in aggregate, dramatically underperformed the S&P 500 index, this time by an embarrassing 15.6 percentage points. In analyzing almost 4 years of returns for these 10 companies we find that they lag the S&P 500 by 14.3 percentage points, posting an overall loss in value of over 11 percent.

If one were to exclude the votes of the three biggest asset managers in the world (Blackrock, Vanguard and State Street, all of which tend to vote to approve almost every CEO pay package presented to them), it would be even more obvious that the number of positive votes is going down dramatically. Together these three funds control between 15 percent and 20 percent of the shares at almost every single public company in America, and their refusal to vote against more than just a very, very few CEO pay packages stands out. A recent paper by Harvard Law School professors Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst analyzed these asset managers and found that they have strong incentives to under-invest in stewardship and defer excessively to the preferences and positions of corporate managers.5

PROXY ADVISOR VOTING RECOMMENDATIONS ON CEO PAY PACKAGES

Financial managers often rely on proxy advisors to evaluate CEO pay packages. The two largest advisors are Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis, but there are also several smaller advisors, such as Egan Jones, Segal Marco and PIRC. In 2018 lobbyists for big business attacked these firms suggesting that fund managers were blindly following their advice.

In fact, it appears that many funds that subscribe to ISS and Glass Lewis vote to approve numerous CEO pay packages that these advisory services advise to vote against. Proxy Insight, an independent data provider tracking the voting records and policies of more than 1,700 global investors, conducted an analysis 6 of investor voting correlation with recommendations from ISS and Glass Lewis and found “a clear divergence in actual voting behavior compared to proxy advisor vote recommendations.” (Proxy Insight filed this analysis as an SEC comment letter.) Specifically, Proxy Insight analyzed the voting of the largest 20 asset managers on CEO pay packages at S&P 1500 companies during the period July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2018. The analysis showed that when ISS and Glass Lewis recommended “against” a pay package, the correlation of voting with recommendations was low.

ISS recommended voting against 11.8 percent of the CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and 33 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. These percentages have been fairly unchanged year after year. These numbers are based on the default ISS “standard” policy. ISS also offers some specific ESG policies. This year the ISS SRI policy recommended against approximately 14 percent of these pay packages, and a policy tailored to Taft-Hartley pension plans, recommended against 24 percent. Many users of ISS proxy voting services take advantage of ISS’s ability to create additional custom policies. In the case of CEO pay these custom policies can produce substantial differences from the standard ISS recommendations.

ISS uses a quantitative degree-of-alignment scale to evaluate pay and performance. According to FAQs issued December 2018, ISS will “continue to explore the potential for future use of Economic Value Added (EVA) measures to add additional insight into a company's financial performance” and will display those measures in reports this year.7 Glass Lewis recommended shareholders vote against 9.5 percent of CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and 27 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. These figures are lower than they have been in previous years.

Glass Lewis recommended shareholders vote against 9.5 percent of CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and 27 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. These figures are lower than they have been in previous years.

Glass Lewis, which can also create custom policies, uses a model comparing CEO pay in relation to company peers, and company performance compared to peers, and awards letter grades between A and F. An “A” means that “the company’s percentile rank for executive compensation is significantly less than its percentile rank for company performance.”8

Egan-Jones Proxy Services recommended voting against approximately 30 percent of the CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and against 49 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. Egan-Jones reported to us that in five cases where they did vote in favor of the CEO pay vote, they had opposed stock award or omnibus plans at the same companies.

Segal Marco Advisors, which has one of the most rigorous analyses of CEO pay packages, recommended shareholders vote against 42 percent of CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and 70 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. Maureen O’Brien, vice president and director of corporate governance, notes that the Segal Marco Advisors cast votes for 84 funds that subscribe directly for proxy voting and corporate governance services and additional funds that receive consulting or discretionary services. When analyzing compensation, Segal Marco does a first screen to identify corporations with good financial performance and less-than-anticipated pay. Those companies generally receive a “yes” vote. Those that don’t fit in that category receive a secondary screening on a variety of pay practices (from accelerated vesting to gross-ups).

PIRC, one of the largest proxy advisors in Europe, recommended voting against approximately 72 percent of the CEO pay packages at S&P 500 companies, and 90 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEOs.

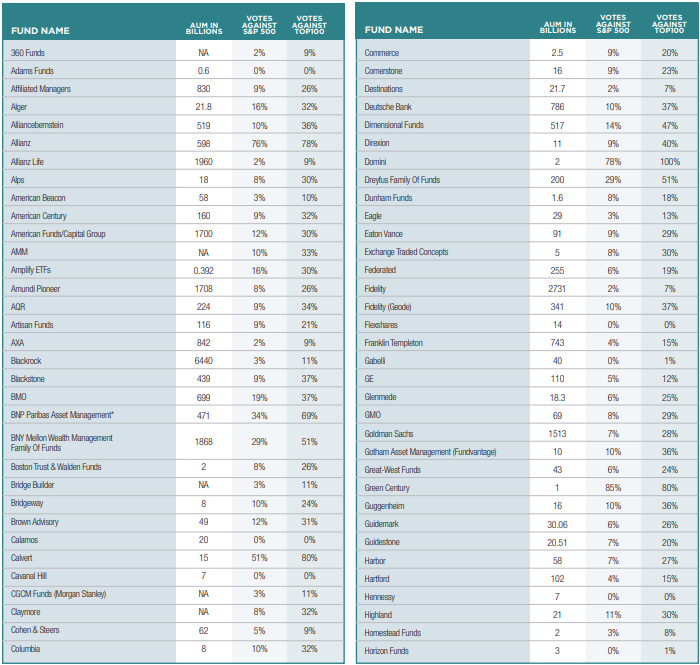

VOTES OF MANAGERS OF MUTUAL FUNDS AND ETFS

We have analyzed how the largest investors in S&P 500 companies, namely mutual funds, ETFs, and public pension funds, have voted their shares on the issue of CEO pay. This enables us to see which funds are exercising their fiduciary responsibility and which are acquiescing to management in squandering company resources.

The mutual fund section of the report was based on data provided by Morningstar Fund Votes database. An explanation of the Unique Vote count methodology they use can be found in Appendix D.

See Appendix D for a full list as well as an explanation of the methodology used in calculating votes. Assets Under Management (AUM) are from Proxy Insight, and taken from most recent data in ADV forms filed at the SEC.

One estimate found that as of Dec. 31, 2017, BlackRock, Vanguard, and SSGA held positions of more than $1 billion in 353, 427, and 242 S&P 500 companies, respectively9. Rick Warzman recently wrote in “When it comes to investment giants furthering social good, many see a disconnect between words and action” that “the investment giants all seem to be saying the right things” but their voting does not match. Warzman quotes long-time investor advocate Tim Smith who notes that, “Confidential dialogue is vitally important, but quiet conversation combined with . . . a proxy vote sends a much clearer and less ambiguous message.”10

An important paper by Harvard’s Lucian Bebchuk and Scott Hirst, “Index Funds and the Future of Corporate Governance: Theory, Evidence, and Policy”, examines the reluctance of Blackrock, Vanguard, and State Street to vote against management. The study demonstrates “that index funds managers have strong incentives to (i) under-invest in stewardship and (ii) defer excessively to the preferences and positions of corporate managers.”11 They claim that there is no financial incentive for these managers to engage in serious stewardship. In addition, they also claim that deferring to management “could also affect the private interests of the index fund manager.” The deference can spring from a “web of financially-significant business ties” (for example, managing a firm’s 401(k) plan), or from fear of public or political backlash.

The paper concludes with a number of potential reforms, one of which – bring transparency to private engagements – SSGA has already begun.

In a separate paper, Patrick Jahnke interviewed 29 individuals from 20 institutional investors (managing a combined $13.3 trillion) for his paper “Asset Manager Stewardship and the Tension Between Fiduciary Duty and Social License.” Jahnke notes that, in the past it had been a winning strategy to remain neutral, and “kept [large fund managers] out of the limelight and away from regulatory interest, while maximizing the potential client base.” However, he believes it is “doubtful that the same strategy will work in the future, now that asset managers have grown to such a size that they have become household names.” As Jahnke notes, “In a democratic capitalist society, failure to” maintain the “social license” or perceived legitimacy may result in consumer boycotts and “ultimately in calls for stricter regulation.”12

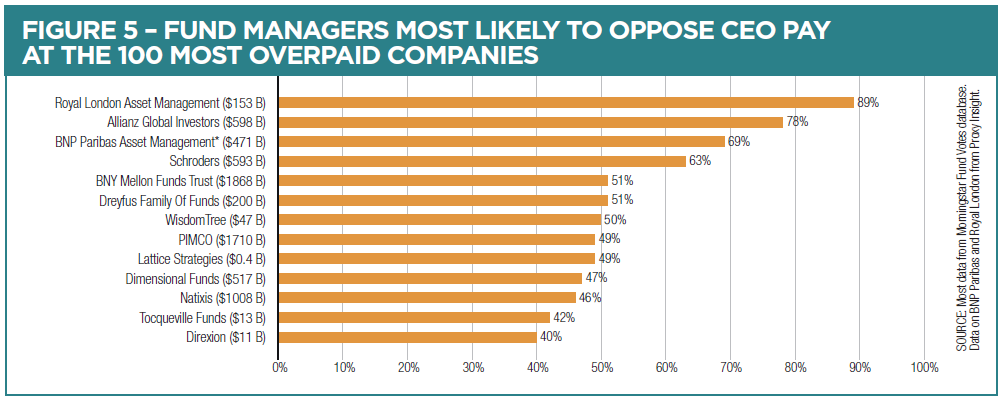

Despite this, Figure 5 shows more funds are voting against more packages. This year there were 87 funds that voted against more than half of the 100 overpaid CEOs.

Below we include profiles of a number of fund managers. We selected those to focus on based on a number of factors including fund practices, changes in guidelines or practices, responsiveness to outreach, and whether they had been profiled in prior years.

Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI) – AUM $786 billion

Aberdeen Standard voted against 33 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it held just of the 19 of the companies with 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages, and voted against 57 percent of them.

One of the largest changes in levels of voting opposition occurred because of an August 2017 merger between Standard Life and Aberdeen Asset Management, forming a new firm renamed Aberdeen Standard Investments (ASI). As its own company, as covered in last year’s report, Standard Life, which had approximately $384 billion in AUM, opposed only 9.4 percent of CEO pay packages in the S&P 500 in 2017. As part of this merger a new ASI custom policy was implemented for 2018, which included “amended … parameters applied to remuneration votes in North America,” according to a Jan. 17, 2018 email to As You Sow from Mike Everett, ESG Investment Director for ASI.

The votes of the newly merged company are similar to those of Aberdeen in prior years, but now represent approximately twice as many shares, and are much improved over the previous votes by Standard Life.

ASI also issues quarterly Global ESG Investment reports, which cover broad topics as well as details of engagement with specific companies. In its Quarter 3 2018 report, ASI discussed how companies should respond to failed CEO pay advisory votes in the context of one particular engagement. “We are increasingly concerned that, where companies receive high levels of dissent on advisory votes on pay, the only solution offered is more engagement with shareholders…Engagement alone is not enough.” writes Governance and Stewardship Director Deborah Gilshan in that report.13

Allianz Global Investors voted against 75 percent of the pay packages of S&P 500 companies; it voted against 77 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages, and it abstained on an additional 6 percent.14

AllianzGl Analyst Robbie Miles explained in a January 9, 2019 phone interview with As You Sow that, “We apply a corporate governance guideline globally.” The guidelines were completed with the engagement from the full staff, making used of the “thought, wisdom, and experience” of analysts from across the world. The process, according to Miles, was laborious, but left the firm with "confidence that we are representing the views of our fund investors."

"In the U.S. those guidelines are hard on remuneration, because we are taking the view that what is best at incentivizing a human being in Europe is probably what is best an incentivizing a human being in the U.S. or Asia as well," Miles said.

AllianzGl follows three primary beliefs regarding incentives:

- Incentives should be truly long-term, not inspiring tactical moves to boost quarterly earnings but planning for sustainable growth. In other words, a 12-month performance period or immediate vesting may inspire votes against;

- Incentives should be stretching. In many cases common metrics, targets, and thresholds are not suitably stretching. Stock options more often reflect changes in market than rewarding individual effort; and

- Quantum of pay should be in line with peers and performance.

Miles notes that the plans are looked at holistically, with factors ranging from stock ownership guidelines and clawbacks also considered. The AllianzGl Global Proxy Voting Guidelines provide detailed information on the fund’s voting.15

ISS generally does the voting for Allianz using a custom policy that AllianzGl developed with them. If a certain ownership threshold is exceeded, a nine-person ESG team from AllianzGl does additional analysis before the vote is cast.

BlackRock voted against 2.5 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 12 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

BlackRock's disclosure is substantially less useful than that of other funds. In "BlackRock Investment Stewardship Engagement Priorities for 2018," the fund says that it supports “compensation that promotes long-termism." In the paragraph that follows BlackRock mentions that it will "seek clarity," "we expect . . . justification," and "we may ask the board to explain."16

The explanations and justifications Blackrock receives from corporate representatives apparently satisfies it more than anyone else; Blackrock votes to approve more CEO pay packages than almost anyone else.

PIMCO voted against 17.5 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 50 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

This level of opposition represents a significant improvement from 2017, when PIMCO voted against only 1 percent of both the S&P 500 and the 100 most overpaid CEOs.

PIMCO responded to our inquiries noting that the fund used sub-advisors, and proxy voting was done by Parametric Portfolio Associates (PPA).

Seattle–based PPA is an asset manager that works with institutional and individual investors. It also sub-advises a number of mutual funds. These are reported on the respective NP-X filings for each fund, including some for those of parent company Eaton Vance.

Jennifer Sireklove, PPA Director of Responsible Investing, told As You Sow that a new process and structure around proxy voting went into effect in February 2018. The emphasis on more active voting is "tied to our overall thinking on responsible investing." PPA plans to expand its disclosure on its website in the coming year.

SSGA voted against 4 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies and abstained on an additional 2.5 percent; it votedagainst 16 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages, and abstained on an additional 6 percent.

SSGA uses its proxy voting guidelines and proprietary compensation screens to identify companies with which there are pay concerns. SSGA reports that screened companies are then "reviewed manually by the Asset Stewardship Team to reach a vote decision. The team reviews over 1,400 pay votes annually."

In April 2018, SSGA announced a policy change with a document titled, “Transparency in Pay Evaluation: Adoption of Abstain as a Vote Option on Management Compensation Resolutions.” This codified and explained its new policy of abstaining, rather than its previous policy of voting for, the CEO pay package that State Street had serious reservations about.17

Rakhi Kumar, head of SSGA's Investment Stewardship Team in a November 2018 interview told the Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation that the level of "unqualified support for pay proposals has fallen in general. Overall unqualified support from a global perspective fell from 83 to 78 percent. In the U.S. there were 2,300 executive compensation votes—of that, 59 total votes (2.5 percent) were abstains compared to 139 votes 'against' (6 percent)."18

Unlike similar reports issued by peers, SSGAs 2017 Stewardship report names names and lists companies that have adopted specific reforms. For example, "VeriFone Systems, Inc., and Exelon Corporation acted to improve their compensation structure by eliminating upward discretion in payouts and placing a cap on long performance plan awards in the event of negative absolute total shareholder return (TSR)." SSGA also notes that total CEO compensation at Honeywell has been reduced over time, in part due to SSGA’s engagement.19

Vanguard voted against 3.5 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 14 percent of the 100 overpaid CEO pay packages.

This represents a small upward trend. Two years ago, Vanguard voted against only 1.3 percent of the S&P 500. Vanguard’s votes do not appear to represent the view of Vanguard's founder, recently deceased John Bogle, who wrote, "CEO compensation is seriously out of line, and too often has provided excessive and unreliable lottery-type rewards based on evanescent stock prices rather than durable intrinsic corporate value."20

In its Annual Stewardship Report, Vanguard did identify executive compensation as one of its four areas of concern, yet it rarely votes against CEO pay packages. According to the report, "We discussed executive compensation in about half our engagements. The alignment of pay with relative performance and the magnitude of total compensation were prominent themes in our discussions on this topic." The report goes on to describe seven specific engagements – without naming the companies involved – including two where the fund voted against the packages.

Vanguard, the report continued, "voted against 318 compensation committee members for failing to act on compensation matters in response to shareholder feedback."21

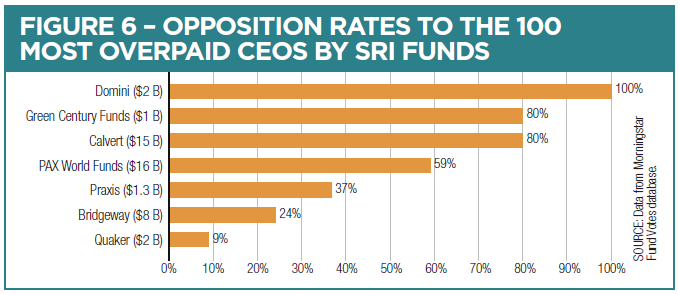

Socially Responsible Investing Funds

Many individuals who wish to align their investments – and the shareholder proxy voting of their investments – with their values opt to invest in socially responsible investing (SRI) funds.

As can be seen in Figure 6, some SRI funds are now more likely to vote against excessive pay packages. Notably, Green Century funds formerly had a policy to abstain from all votes on CEO compensation. In its 2018 guidelines that policy changed. The guidelines now read “Green Century will also vote in favor of ‘say on pay’ resolutions for compensation packages that are sustainable and equitable.”22 This year, that policy resulted in opposing 80 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

Praxis has informed As You Sow that its policy on voting on compensation proposals is under review in preparation for the 2019 proxy season.

Trillium does not appear on the chart this year because it held fewer than 10 of the 100 most overpaid CEOs. However, it voted against pay at all of them, as well as at all of the 46 S&P 500 companies in its portfolio.

VOTES BY PENSION FUNDS

As Figure 7 illustrates, pension funds typically have a higher level of opposition to overpaid CEOs than mutual funds.

California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) – AUM $351 billion AUM

CalPERS voted against 45.4 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 73 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

This represented a marked improvement. Last year CalPERS voted against only 17 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 and 53 percent of the overpaid CEO pay packages.

The improvement came from a policy change reported in Pension & Investments, which noted "In 2018, CalPERS officials increased their level of scrutiny when reviewing a company's pay and performance practices, casting a wider net of company plans it would oppose and including more factors such as CEO pay ratio information."23 Simiso Nzima, CalPERS's investment director of global equity governance, explained in multiple interviews that the primary issue was pay beyond what was merited for performance. Specifically, Nzima told Chief Investment Officer,24 "If the CEO pay is going up and the return to shareholders is not, then we do not support that."

Florida State Board of Administration – AUM $203 billion

The Florida State Board of Administration (FSBA) voted against 54.4 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 79.8 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

In each year of our report, FSBA has been one of the pension funds that voted against the highest number of overpaid CEO pay packages. FSBA receives reports from both Glass Lewis and ISS, as well as data from Meridian and other advisors, and analyzes the data to make decisions in-house.

In an Oct. 31, 2018 email to As You Sow, Tracy Stewart, senior corporate governance analyst at FSBA, said many of the votes against are based on a lack of adequate disclosure of metrics, thresholds and targets. "Our voting policy does not support a compensation program unless we understand how it is incentivizing performance, and we approve of the metrics, thresholds, and targets used," Stewart said. "Disclosure of metrics as well as targets and thresholds is an important part of our voting decisions, because we don't approve things we don’t understand, and you can't understand what you don't know."

For example, FSBA would likely vote against a plan that "discloses a metric such as EPS [earnings per share], but the threshold and targets the plan uses are far below any recent performance by the company and have been at the same level for years, without discussion or justification." Stewart points out, "If we vote against one program for disclosing inappropriately low targets, we can't and shouldn't support another program that doesn’t disclose them at all."

This emphasis of disclosure of targets came up repeatedly, with multiple funds. "It isn't enough for a company to provide the metrics they use; we need to know levels of thresholds and targets as well," Stewart said. "We need to see the company is using an objective program that focuses executives in advance on the right measures of performance and uses tough but fair performance requirements."

Los Angeles County Employees Retirement Association (LACERA) – AUM $56 billion

LACERA voted against 13 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 42 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

According to the fund's Proxy Voting Results and Trends25 report for fiscal Year 2018, overall level of support for CEO pay packages decreased from 86 percent in 2016 to 75 percent in 2018, due to a "move to custom policy with emphasis on pay-forperformance."

Votes are cast in adherence to LACERA’s Corporate Governance Principles adopted in February 2018.26 Each of the principles (accountability, integrity, aligned interest, transparency and prudent risk mitigation) has implications for compensation analyses. LACERA is also moving from comingled funds to separately managed accounts where they will maintain voting authority, which will sharply increase LACERA’s proxy voting activity.

New York State Common Retirement Fund – $192 billion AUM

New York State voted against 26 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500; it voted against 53 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages. This represents the continuation of a trend of increasing opposition. Last year the fund opposed pay at only 17.5 percent of S&P 500 companies.

In addition to improving its voting practices, New York State, under the leadership of New York State Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli, has filed shareholder resolutions and negotiated with companies to “reexamine their CEO and executive pay and adopt policies that take into account the compensation of the rest of their workforces.” In December 2018, the New York State Common Retirement Fund announced it had reached agreements with Microsoft Corp., CVS Health Corp., Macy's Inc., The TJX Companies Inc., and Salesforce.com and withdrew its shareholder resolutions with the companies. "We are encouraging companies to adopt policies that take their entire workforce into consideration rather than setting CEO pay solely by benchmarking it against other CEOs," noted DiNapoli in a press release.27

Pennsylvania State Employees’ Retirement System (PSERS) – AUM $28 billion

Pennsylvania SERS voted against 7.6 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 29 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

While very low, PSERS's recent performance represents a steep increase from the prior year, when it voted in favor of every CEO pay package. Following that disclosure in our report, an investigation was conducted. Pamela Hiles, acting director of communications and policy for PSERS, told the Council of Institutional Investors, "ISS indicated that due to an internal miscommunication within the ISS team, it incorrectly executed say-on -pay votes on SERS' behalf" In addition, CII noted, "an additional layer of review and sign-off has been added to the controls ISS currently has in place and the proxy advisor and PSERS have quarterly calls to review the proxy votes."28

State of Rhode Island – AUM $8 billion

Rhode Island voted against 14 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies over the past proxy season; it voted against 36 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

Since taking office in 2015, State Treasurer Seth Magaziner has been focused on "working to encourage companies to adopt responsible business practices, so that they are sustainable for years to come." He moved the state’s proxy voting decisions in house, rather than deferring to recommendations from an advisory service.29 Opposition votes are likely to be much higher in the upcoming proxy season. In September 2018, Rhode Island adopted new guidelines. On CEO pay, the fund included somewhat standard language regarding the analysis: "Vote against management say on pay proposals where there is a misalignment between CEO pay and company performance; the company maintains problematic pay practices; the board exhibits a significant level of poor communication and responsiveness to shareholders or if the board has failed to demonstrate good stewardship of investors’ interests regarding executive compensation practices." It included a specific matrix as well, noting that votes will be cast against packages in which:

- CEO pays is above 75th percentile of peers and company performance is below peer median;

- Performance-based pay is less than 50 percent of CEO compensation;

- CEO pay exceeds 4 times named executive officer (NEO)pay;

- Potential dilution from equity-based incentives exceeds 4 percent of shares outstanding.30

State Board of Investments of Minnesota (SBI) – AUM $93 billion

Minnesota's SBI voted against 77.4 percent of pay packages of the S&P 500 companies; it voted against 91.7 percent of the 100 most overpaid CEO pay packages.

The State Board of Investments of Minnesota (SBI) votes proxies for Minnesota State Retirement System (MSRS), Public Employees Retirement Association (PERA), and Teachers Retirement, based on the guidance of a four-person proxy committee made up of one individual each from the offices of the governor, secretary of state, attorney general, state auditor. The group is interested in promoting compensation plans that align management and shareholders. The biggest drivers of votes against CEO pay packages are low performance grades, poor disclosure practices, excise tax gross ups and single trigger change-in-control provisions. Like other funds, SBI votes against any plans that receive D or F pay for performance grades from Glass Lewis. For funds with C grades, they vote against in several circumstances:

- Total compensation to CEO is four times more than the average NEO;

- Excessive NEO compensation compared to its Peer Group;

- Poor company performance compared to its competitors;

- Poor disclosure of compensation practices

Pension funds that approve most CEO pay packages:

Employee Retirement System of Georgia (ERSG)

The trustees of the ERSG adopted has a policy to “vote and execute all voting proxies in support of management” with an exception if the Chief Investment Officer and the Co-Chief Investment Officer of the Division of Investment Services believe that “such a vote would be detrimental to the best interests or rights of the Retirement System.” According to data collected by Proxy Insight, the fund voted against only one of the overpaid CEOs: Verizon.31

Pension funds with lots of External Managers and many Comingled funds

Far more common than funds with explicit guidelines to routinely support management are funds that delegate their voting responsibilities to external managers, without providing directions on voting matters. In some cases, a fund may have just four or five managers for U.S. public equities. In other cases, it is more complex. One fund told us it had “contracts with 14 external investment advisors who managed 22 portfolios that comprised 77.3 percent of the U.S. Public Equity portfolio.”

Thus, we (and they) are unable to create assessments on how their shares are voted on the CEO pay or any other issue. As we’ve noted before, many financial fund managers are more inclined than the pension funds themselves to approve expensive CEO pay packages. While there are some managers that have significant levels of opposition, those tend not to be the ones that these pension funds use. In fact, BlackRock is by far the most common external money manager.

Examples of public funds that use external managers, often with comingled funds, include:

The State of Missouri delegates to individual investment managers the responsibility for voting proxies in the best interests of the members of the system’s members. According to the PSRS/PEERS of Missouri Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, the largest fund manager for large-cap equity is BlackRock.32

Iowa Public Employees Retirement Systems uses comingled funds at BlackRock and Mellon Capital Management, which vote quite differently. It has separate accounts at Columbia, J.P Morgan, Panagora Asset and Wellington Management. In all cases managers are allowed to vote proxies according to their own policies.

Voting for Idaho Public Employees Retirement Systems is handled externally by the following managers: Peregrine, Tukman, and MCM.

Nevada Public Employees Retirement Systems has assets with Alliance Bernstein and BlackRock, who have different voting records, and smaller percentages with two others funds.

PAY RATIO DISCLOSURE

When shareholders were evaluating compensation packages in spring 2018, they had a new piece of information: the ratio of the pay of the CEO to the pay of the corporation’s median worker. This was due to the implementation of a much-delayed provision of the Dodd-Frank Act that recently took effect.

The AFL-CIO has been tracking these ratios as they appear in company proxy statements. The average of these CEO pay to median worker pay ratios as of Sep. 5, 2018 was approximately 273:1. This contrasts sharply with around the world as reported in a BBC article. In the United Kingdom — the only other non-U.S. country besides India where CEOs make more than 200 times their employees — the ratio is estimated at 201:1. In the Netherlands the ratio is 171:1; in Switzerland it is 152:1. In Germany, where workers are represented on boards of directors, it is 136:1.33

This information can be quite illustrative of pay practices at particular companies. For example, we learned this year that the median employee at Walmart, which has appeared on our overpaid CEO list for several years, was paid $19,177, and the pay ratio of the CEO to median worker was 1,188:1.

On the other hand, Costco’s median employee was paid $38,810, and the CEO’s pay, while in the multi-millions, is much lower than at Walmart. The Costco CEO to median worker pay ratio was 191:1, one fifth of the ratio at Walmart.

While we did not include pay ratio as a criterion in identifying overpaid CEOs, we did find a predictable correlation between our list of overpaid CEOs and the pay ratio. The median pay ratio for the S&P 500 is 142:1, while the median for companies on As You Sow’s list of the 100 most overpaid CEOs is over twice as much, namely 300:1. In comparing our overpaid list to pay ratio data collected by the AFL-CIO, we found that the vast majority of the companies we identified were in the highest quartile of pay ratios.

It is not clear how funds will use this information. As Jocelyn Brown, senior investment manager at RPMI Railpen, told us, “On pay ratios, we recognize it is early days, and, like many others, we would be cautious of putting too much focus on a single number without seeing how it compares to peers and changes over time.”

Établissement de Retraite Additionnelle de la Fonction Publique (ERAFP), the asset manager for France’s public pension fund, does have a rule on pay ratios, as described in the UN PRI report: “ERAFP has set a ‘socially acceptable maximum amount of total remuneration,’ inclusive of salary, benefits, options, bonus shares, and top-up pension plan contributions, at ‘100 times the minimum salary in force in the country in which the company’s registered office is located.’”34

We expect any policies on using pay ratio as a criterion in voting on pay packages to evolve slowly over time. It is likely, however, that the newly disclosed number will soon be one of many factors shareholders consider when voting on the CEO pay package.

Pay ratio information is also being used in taxation. The city of Portland, Oregon “levies a 10 percent surtax on firms that surpass [a ratio of 100:1]. It rises to 25 percent on firms with pay gaps exceeding 250 to 1.” Similar pay gap tax bills have been introduced in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Rhode Island. On the federal level Representative Mark DeSaulnier (D-CA), has proposed similar legislation.35

CONCLUSION

Addressing the Council of Institutional Investors meeting in fall 2018, Carol Bowie, who for years led the compensation analysis team at ISS, said, “The key to moderating and controlling CEO pay is investors. They are really the only solution.”

She’s right.

In the five years As You Sow has been publishing this report, our research has increasingly demonstrated that all investors, from managers of the largest asset funds to the individuals contributing to a public pension or a 401(k) plan, can play a critical role in the effort to reverse the practices that have allowed CEO compensation packages to rise unabated — often without any nexus to corporate performance.

As we’ve noted in this report, the UN PRI and other studies have shown why shareholder engagement matters. “Voting against excessive pay proposals offers a tool that investors can use to intervene when proposed compensation appears to be out of line with their interests or with a sense of appropriateness.”36

In this report we’ve showcased how investors have taken a stance to moderate the excesses of CEO pay, highlighting corporate behaviors that have most frequently triggered votes against irresponsible compensation packages. Fund managers have a fiduciary obligation to consider these practices when deciding whether to support specific compensation packages. By connecting questionable corporate tactics and “no” votes on CEO compensation, this report can serve as a roadmap for institutional investors to consider revisiting their guidelines to, as PRI puts it, “reframe how CEO compensation is incentivized.”37

But the right — and responsibility — to be a watchdog does not rest with the funds alone. All shareholders can and must hold their funds accountable to ensure that corporations they entrust with their money are acting as proper stewards of their investments.

Every investor has a role to play. Union leaders should speak to their fund trustees. Teachers should contact funds such as TIAA/Nuveen; state and local government employees should reach out to their employers and their pension funds. Individual investors concerned about votes can offer feedback to their money managers; they may also choose to move their retirement accounts to social investment funds (and, in the process, let prior funds know they’re doing so, and why).

We concluded our 2018 study by urging shareholders to have their voices heard. We’re pleased to say that this advice is beginning to take hold — progress is evident in this 2019 report. But there is a long way to go.

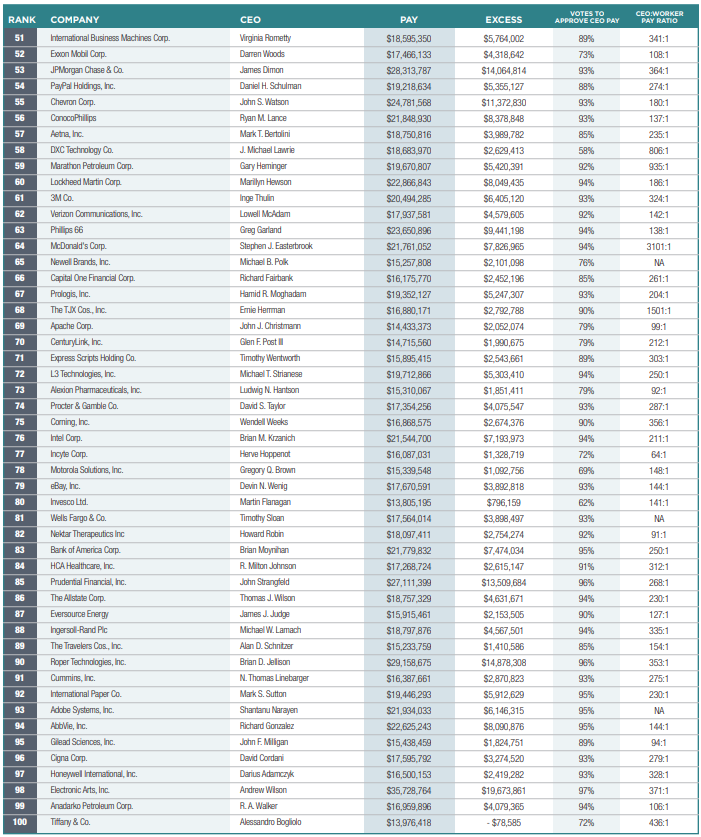

APPENDIX A – THE 100 MOST OVERPAID CEOs

Highlight the titles in any column to sort numerically or alphabetically.

Rank |

Company |

CEO |

Pay |

Excess |

Votes to Approve CEO Pay |

CEO:Worker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Fleetcor Technologies Inc | Ronald F. Clarke | 52,643,810 |

38,159,825 |

14% |

1517 |

2 |

Oracle Corp. | Mark V. Hurd/Safra Catz | 81,562,244 |

67,900,531 |

49% |

907 |

3 |

Broadcom, Inc. | Hock Tan | 103,211,163 |

86,868,639 |

62% |

NA |

4 |

Mondelez International, Inc. | Dirk Van de Put | 42,442,924 |

28,757,373 |

45% |

990 |

5 |

Wynn Resorts Ltd. | Stephen Wynn | 34,522,695 |

20,906,213 |

20% |

777 |

6 |

The Walt Disney Co. | Robert Iger | 36,283,680 |

22,408,282 |

46% |

787 |

7 |

TransDigm Group, Inc. | W. Nicholas Howley | 61,023,102 |

46,040,922 |

64% |

1306 |

8 |

American International Group, Inc. | Brian Duperreault | 43,086,861 |

29,693,425 |

62% |

671 |

9 |

Mattel, Inc. | Margaret H. Georgiadis | 31,275,289 |

19,264,188 |

46% |

4987 |

10 |

CSX Corp. | E. Hunter Harrison | 151,147,286 |

136,387,791 |

78% |

1531 |

11 |

Discovery, Inc. | David M. Zaslav | 42,247,984 |

29,692,839 |

69% |

NA |

12 |

TripAdvisor, Inc. | Stephen Kaufer | 47,933,462 |

35,018,668 |

75% |

481 |

13 |

Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. | Gary A. Norcross | 29,141,610 |

14,606,759 |

56% |

654 |

14 |

Ameriprise Financial, Inc. | James Cracchiolo | 23,900,309 |

9,879,197 |

25% |

223 |

15 |

Ventas, Inc. | Debra A. Cafaro | 25,254,607 |

11,969,664 |

59% |

285 |

16 |

Halliburton Co. | Jeffrey A. Miller | 23,078,364 |

9,828,762 |

43% |

290 |

17 |

Expedia Group, Inc. | Mark D Okerstrom | 30,720,457 |

16,588,563 |

79% |

428 |

18 |

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Leonard S. Schleifer | 26,508,058 |

12,855,143 |

67% |

215 |

19 |

Jefferies Financial Group, Inc. | Richard B. Handler | 21,787,285 |

8,862,271 |

51% |

489 |

20 |

IQVIA Holdings, Inc. | Ari Bousbib | 38,029,517 |

23,710,232 |

88% |

388 |

21 |

Comcast Corp. | Brian Roberts | 32,520,224 |

18,700,417 |

87% |

458 |

22 |

Allergan Plc | Brenton Saunders | 32,827,626 |

19,362,274 |

91% |

349 |

23 |

Schlumberger NV | Paal Kibsgaard | 20,759,340 |

7,653,135 |

66% |

234 |

24 |

Netflix, Inc. | Reed Hastings | 24,377,499 |

6,717,787 |

61% |

133 |

25 |

AT&T, Inc. | Randall Stephenson | 28,720,720 |

15,455,913 |

90% |

366 |

26 |

BlackRock, Inc. | Laurence D. Fink | 27,743,233 |

13,534,946 |

89% |

195 |

27 |

Ralph Lauren Corp. | Patrice Louvet | 23,792,036 |

11,075,567 |

88% |

1038 |

28 |

Omnicom Group, Inc. | John D. Wren | 23,959,325 |

10,454,317 |

87% |

596 |

29 |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. | Marc N. Casper | 22,275,176 |

7,849,780 |

77% |

324 |

30 |

General Dynamics Corp. | Phebe Novakovic | 21,501,429 |

6,989,333 |

68% |

218 |

31 |

Centene Corp. | Michael F. Neidorff | 25,259,468 |

9,720,247 |

88% |

379 |

32 |

Duke Energy Corp. | Lynn Good | 21,415,936 |

7,842,750 |

82% |

175 |

33 |

Johnson & Johnson | Alex Gorsky | 29,802,564 |

16,064,973 |

92% |

452 |

34 |

PepsiCo, Inc. | Indra Nooyi | 31,082,648 |

17,426,678 |

92% |

650 |

35 |

Booking Holdings, Inc. | Glenn D. Fogel | 27,774,458 |

13,381,993 |

91% |

599 |

36 |

McKesson Corp. | John H. Hammergren | 18,143,017 |

4,845,682 |

27% |

473 |

37 |

Raytheon Co. | Thomas A. Kennedy | 24,883,871 |

9,998,351 |

90% |

172 |

38 |

The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. | Lloyd Blankfein | 21,995,266 |

8,317,965 |

88% |

163 |

39 |

Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. | James Murdoch | 20,315,944 |

6,402,830 |

78% |

300 |

40 |

Western Digital Corp. | Stephen Milligan | 17,907,624 |

4,381,912 |

42% |

1628 |

41 |

Walmart, Inc. | C. Douglas McMillon | 22,791,276 |

9,372,617 |

91% |

1188 |

42 |

Lennar Corp. | Stuart Miller | 19,127,533 |

5,499,861 |

77% |

NA |

43 |

Valero Energy Corp. | Joseph W. Gorder | 22,532,260 |

7,417,930 |

87% |

117 |

44 |

Pfizer Inc. | Ian Read | 27,913,775 |

14,246,994 |

93% |

313 |

45 |

Activision Blizzard, Inc. | Robert A. Kotick | 28,698,375 |

12,835,277 |

92% |

306 |

46 |

American Express Co. | Kenneth Chenault | 18,611,373 |

5,084,279 |

70% |

327 |

47 |

Humana, Inc. | Bruce Broussard | 19,768,523 |

4,686,890 |

66% |

344 |

48 |

Freeport-McMoRan, Inc. | Richard Adkerson | 18,396,037 |

5,864,506 |

87% |

277 |

49 |

SL Green Realty Corp. | Marc Holliday | 17,407,821 |

4,008,284 |

61% |

303 |

50 |

Abbott Laboratories | Miles White | 18,971,019 |

4,949,219 |

79% |

251 |

51 |

International Business Machines Corp. | Virginia Rometty | 18,595,350 |

5,764,002 |

89% |

341 |

52 |

Exxon Mobil Corp. | Darren Woods | 17,466,133 |

4,318,642 |

73% |

108 |

53 |

JPMorgan Chase & Co. | James Dimon | 28,313,787 |

14,064,814 |

93% |

364 |

54 |

PayPal Holdings, Inc. | Daniel H. Schulman | 19,218,634 |

5,355,127 |

88% |

274 |

55 |

Chevron Corp. | John S. Watson | 24,781,568 |

11,372,830 |

93% |

180 |

56 |

ConocoPhillips | Ryan M. Lance | 21,848,930 |

8,378,848 |

93% |

137 |

57 |

Aetna, Inc. | Mark T. Bertolini | 18,750,816 |

3,989,782 |

85% |

235 |

58 |

DXC Technology Co. | J. Michael Lawrie | 18,683,970 |

2,629,413 |

58% |

806 |

59 |

Marathon Petroleum Corp. | Gary Heminger | 19,670,807 |

5,420,391 |

92% |

935 |

60 |

Lockheed Martin Corp. | Marillyn Hewson | 22,866,843 |

8,049,435 |

94% |

186 |

61 |

3M Co. | Inge Thulin | 20,494,285 |

6,405,120 |

93% |

324 |

62 |

Verizon Communications, Inc. | Lowell McAdam | 17,937,581 |

4,579,605 |

92% |

142 |

63 |

Phillips 66 | Greg Garland | 23,650,896 |

9,441,198 |

94% |

138 |

64 |

McDonald's Corp. | Stephen J. Easterbrook | 21,761,052 |

7,826,965 |

94% |

3101 |

65 |

Newell Brands, Inc. | Michael B. Polk | 15,257,808 |

2,101,098 |

76% |

NA |

66 |

Capital One Financial Corp. | Richard Fairbank | 16,175,770 |

2,452,196 |

85% |

261 |

67 |

Prologis, Inc. | Hamid R. Moghadam | 19,352,127 |

5,247,307 |

93% |

204 |

68 |

The TJX Cos., Inc. | Ernie Herrman | 16,880,171 |

2,792,788 |

90% |

1501 |

69 |

Apache Corp. | John J. Christmann | 14,433,373 |

2,052,074 |

79% |

99 |

70 |

CenturyLink, Inc. | Glen F. Post III | 14,715,560 |

1,990,675 |

79% |

212 |

71 |

Express Scripts Holding Co. | Timothy Wentworth | 15,895,415 |

2,543,661 |

89% |

303 |

72 |

L3 Technologies, Inc. | Michael T. Strianese | 19,712,866 |

5,303,410 |

94% |

250 |

73 |

Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Ludwig N. Hantson | 15,310,067 |

1,851,411 |

79% |

92 |

74 |

Procter & Gamble Co. | David S. Taylor | 17,354,256 |

4,075,547 |

93% |

287 |

75 |

Corning, Inc. | Wendell Weeks | 16,868,575 |

2,674,376 |

90% |

356 |

76 |

Intel Corp. | Brian M. Krzanich | 21,544,700 |

7,193,973 |

94% |

211 |

77 |

Incyte Corp. | Herve Hoppenot | 16,087,031 |

1,328,719 |

72% |

64 |

78 |

Motorola Solutions, Inc. | Gregory Q. Brown | 15,339,548 |

1,092,756 |

69% |

148 |

79 |

eBay, Inc. | Devin N. Wenig | 17,670,591 |

3,892,818 |

93% |

144 |

80 |

Invesco Ltd. | Martin Flanagan | 13,805,195 |

796,159 |

62% |

141 |

81 |

Wells Fargo & Co. | Timothy Sloan | 17,564,014 |

3,898,497 |

93% |

NA |

82 |

Nektar Therapeutics Inc | Howard Robin | 18,097,411 |

2,754,274 |

92% |

91 |

83 |

Bank of America Corp. | Brian Moynihan | 21,779,832 |

7,474,034 |

95% |

250 |

84 |

HCA Healthcare, Inc. | R. Milton Johnson | 17,268,724 |

2,615,147 |

91% |

312 |

85 |

Prudential Financial, Inc. | John Strangfeld | 27,111,399 |

13,509,684 |

96% |

268 |

86 |

The Allstate Corp. | Thomas J. Wilson | 18,757,329 |

4,631,671 |

94% |

230 |

87 |

Eversource Energy | James J. Judge | 15,915,461 |

2,153,505 |

90% |

127 |

88 |

Ingersoll-Rand Plc | Michael W. Lamach | 18,797,876 |

4,567,501 |

94% |

335 |

89 |

The Travelers Cos., Inc. | Alan D. Schnitzer | 15,233,759 |

1,410,586 |

85% |

154 |

90 |

Roper Technologies, Inc. | Brian D. Jellison | 29,158,675 |

14,878,308 |

96% |

353 |

91 |

Cummins, Inc. | N. Thomas Linebarger | 16,387,661 |

2,870,823 |

93% |

275 |

92 |

International Paper Co. | Mark S. Sutton | 19,446,293 |

5,912,629 |

95% |

230 |

93 |

Adobe Systems, Inc. | Shantanu Narayen | 21,934,033 |

6,146,315 |

95% |

NA |

94 |

AbbVie, Inc. | Richard Gonzalez | 22,625,243 |

8,090,876 |

95% |

144 |

95 |

Gilead Sciences, Inc. | John F. Milligan | 15,438,459 |

1,824,751 |

89% |

94 |

96 |

Cigna Corp. | David Cordani | 17,595,792 |

3,274,520 |

93% |

279 |

97 |

Honeywell International, Inc. | Darius Adamczyk | 16,500,153 |

2,419,282 |

93% |

328 |

98 |

Electronic Arts, Inc. | Andrew Wilson | 35,728,764 |

19,673,861 |

97% |

371 |

99 |

Anadarko Petroleum Corp. | R. A. Walker | 16,959,896 |

4,079,365 |

94% |

106 |

100 |

Tiffany & Co. | Alessandro Bogliolo | 13,976,418 |

-78,585 |

72% |

436 |

NOTE: Due to timing of the SEC rule implementation, some of the companies on the above list were not required to include pay ratio data in the proxy statement covered by this report. If so, we have used pay ratio data that has since been released. These companies are marked with an *. Also, for the purposes of this report, we considered the disclosed pay of the highest paid CEO if there was a CEO change during the year covered.

Appendix B – S&P 500 Companies with Most Shareholder Votes Against CEO Pay

This table shows the 100 companies where the most shareholder votes were cast against the CEO pay package. Vote data from Morningstar Fund Votes database; Compensation data from ISS. These are ranked by level of opposition. The votes are not binding.

Highlight the titles in any column to sort numerically or alphabetically.

Rank |

Company |

CEO |

Votes Against |

Pay |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

Fleetcor Technologies Inc |

Ronald F. Clarke |

86% |

$52,643,810 |

|

2 |

Wynn Resorts Ltd. |

Stephen Wynn |

80% |

$34,522,695 |

|

3 |

Ameriprise Financial, Inc. |

James Cracchiolo |

75% |

$23,900,309 |

|

4 |

McKesson Corp. |

John H. Hammergren |

73% |

$18,143,017 |

|

5 |

Western Digital Corp. |

Stephen Milligan |

58% |

$17,907,624 |

|

6 |

Halliburton Co. |

Jeffrey A. Miller |

57% |

$23,078,364 |

|

7 |

Mondelez International, Inc. |

Dirk Van de Put |

55% |

$42,442,924 |

|

8 |

The Walt Disney Co. |

Robert Iger |

55% |

$36,283,680 |

|

9 |

Mattel, Inc. |

Margaret H. Georgiadis |

54% |

$31,275,289 |

|

10 |

Oracle Corp. |

Mark V. Hurd |

51% |

$81,562,244 |

|

11 |

Jefferies Financial Group, Inc. |

Richard B. Handler |

49% |

$21,787,285 |

|

12 |

Envision Healthcare Corp. |

Christopher A. Holden |

48% |

$7,323,638 |

|

13 |

Johnson Controls International Plc |

George Oliver |

45% |

$12,592,505 |

|

14 |

Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. |

Gary A. Norcross |

44% |

$29,141,610 |

|

15 |

DXC Technology Co. |

J. Michael Lawrie |

42% |

$18,683,970 |

|

16 |

Ventas, Inc. |

Debra A. Cafaro |

41% |

$25,254,607 |

|

17 |

FLIR Systems, Inc. |

James J. Cannon |

40% |

$8,985,273 |

|

18 |

SL Green Realty Corp. |

Marc Holliday |

39% |

$17,407,821 |

|

19 |

Netflix, Inc. |

Reed Hastings |

39% |

$24,377,499 |

|

20 |

Invesco Ltd. |

Martin Flanagan |

38% |

$13,805,195 |

|

21 |

American International Group, Inc. |

Brian Duperreault |

38% |

$43,086,861 |

|

22 |

Broadcom, Inc. |

Hock Tan |

38% |

$103,211,163 |

|

23 |

FMC Corp. |

Pierre Brondeau |

38% |

$13,011,873 |

|

24 |

Harley-Davidson, Inc. |

Matthew Levatich |

37% |

$11,116,676 |

|

25 |

TransDigm Group, Inc. |

W. Nicholas Howley |

36% |

$61,023,102 |

|

26 |

Mylan NV |

Heather Bresch |

34% |

$12,744,397 |

|

27 |

Schlumberger NV |

Paal Kibsgaard |

34% |

$20,759,340 |

|

28 |

Humana, Inc. |

Bruce Broussard |

34% |

$19,768,523 |

|

29 |

Synchrony Financial |

Margaret M. Keane |

34% |

$13,525,503 |

|

30 |

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

Leonard S. Schleifer |

33% |

$26,508,058 |

|

31 |

Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings Ltd. |

Frank Del Rio |

32% |

$10,494,213 |

|

32 |

General Dynamics Corp. |

Phebe Novakovic |

32% |

$21,501,429 |

|

33 |

Ball Corp. |

John Hayes |

31% |

$12,932,654 |

|

34 |

Discovery, Inc. |

David M. Zaslav |

31% |

$42,247,984 |

|

35 |

Motorola Solutions, Inc. |

Gregory Q. Brown |

31% |

$15,339,548 |

|

36 |

Charter Communications, Inc. |

Thomas M. Rutledge |

30% |

$7,813,316 |

|

37 |

American Express Co. |

Kenneth Chenault |

30% |

$18,611,373 |

|

38 |

Incyte Corp. |

Herve Hoppenot |

28% |

$16,087,031 |

|

39 |

Tiffany & Co. |

Alessandro Bogliolo |

28% |

$13,976,418 |

|

40 |

Exxon Mobil Corp. |

Darren Woods |

27% |

$17,466,133 |

|

41 |

Hologic, Inc. |

Stephen MacMillan |

26% |

$11,204,908 |

|

42 |

TechnipFMC Plc |

Douglas J. Pferdehirt |

26% |

$12,688,100 |

|

43 |

Sealed Air Corp. |

Jerome A. Peribere |

26% |

$10,888,951 |

|

44 |

TripAdvisor, Inc. |

Stephen Kaufer |

25% |

$47,933,462 |

|

45 |

Alphabet, Inc. |

Sundar Pichai |

25% |

$1,333,557 |

|

46 |

Newell Brands, Inc. |

Michael B. Polk |

24% |

$15,257,808 |

|

47 |

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. |

Marc N. Casper |

23% |

$22,275,176 |

|

48 |

Lennar Corp. |

Stuart Miller |

23% |

$19,127,533 |

|

49 |

CSX Corp. |

E. Hunter Harrison |

22% |

$151,147,286 |

|

50 |

Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. |

James Murdoch |

22% |

$20,315,944 |

|

51 |

Expedia Group, Inc. |

Mark D Okerstrom |

21% |

$30,720,457 |

|

52 |

Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. |

Ludwig N. Hantson |

21% |

$15,310,067 |

|

53 |

Apache Corp. |

John J. Christmann |

21% |

$14,433,373 |

|

54 |

Abbott Laboratories |

Miles White |

21% |

$18,971,019 |

|

55 |

Martin Marietta Materials, Inc. |

C. Howard Nye |

21% |

$8,989,165 |

|

56 |

CenturyLink, Inc. |

Glen F. Post III |

21% |

$14,715,560 |

|

57 |

CF Industries Holdings, Inc. |

W. Anthony Will |

21% |

$9,462,015 |

|

58 |

Duke Energy Corp. |

Lynn Good |

18% |

$21,415,936 |

|

59 |

Aon Plc |

Gregory C. Case |

17% |

$14,609,682 |

|

60 |

Waters Corp. |

Christopher O'Connell |

17% |

$7,599,988 |

|

61 |

Nielsen Holdings Plc |

Dwight M. Barns |

16% |

$10,202,194 |

|

62 |

UDR, Inc. |

Thomas W. Toomey |

16% |

$7,780,919 |

|

63 |

QUALCOMM, Inc. |

Steven Mollenkopf |

15% |

$11,591,310 |

|

64 |

The Travelers Cos., Inc. |

Alan D. Schnitzer |

15% |

$15,233,759 |

|

65 |

Aetna, Inc. |

Mark T. Bertolini |

15% |

$18,750,816 |

|

66 |

Capital One Financial Corp. |

Richard Fairbank |

15% |

$16,175,770 |

|

67 |

Monster Beverage Corp. |

Rodney Cyril Sacks |

15% |

$12,505,080 |

|

68 |

Equifax, Inc. |

Paulino do Rego Barros Jr. |

15% |

$3,724,434 |

|

69 |

Advance Auto Parts, Inc. |

Thomas R. Greco |

14% |

$6,127,997 |

|

70 |

Vornado Realty Trust |

Steven Roth |

14% |

$10,467,517 |

|

71 |

Willis Towers Watson Plc |

John J. Haley |

13% |

$4,071,068 |

|

72 |

Comcast Corp. |

Brian Roberts |

13% |

$32,520,224 |

|

73 |

F5 Networks, Inc. |

Francois Locoh-Donou |

13% |

$11,892,265 |

|

74 |

Freeport-McMoRan, Inc. |

Richard Adkerson |

13% |

$18,396,037 |

|

75 |

Symantec Corp. |

Gregory S. Clark |

13% |

$6,059,752 |

|

76 |

Valero Energy Corp. |

Joseph W. Gorder |

13% |

$22,532,260 |

|

77 |

Omnicom Group, Inc. |

John D. Wren |

13% |

$23,959,325 |

|

78 |

Qorvo, Inc. |

Robert A. Bruggeworth |

13% |

$6,941,777 |

|

79 |

Ralph Lauren Corp. |

Patrice Louvet |

12% |

$23,792,036 |

|

80 |

The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

Lloyd Blankfein |

12% |

$21,995,266 |

|

81 |

IQVIA Holdings, Inc. |

Ari Bousbib |

12% |

$38,029,517 |

|

82 |

Centene Corp. |

Michael F. Neidorff |

12% |

$25,259,468 |

|

83 |

Kohl's Corp. |

Kevin Mansell |

12% |

$11,339,206 |

|

84 |

PayPal Holdings, Inc. |

Daniel H. Schulman |

12% |

$19,218,634 |

|

85 |

C.H. Robinson Worldwide, Inc. |

John P. Wiehoff |

12% |

$6,834,187 |

|

86 |

Express Scripts Holding Co. |

Timothy Wentworth |

11% |

$15,895,415 |

|

87 |

Macerich Co. |

Arthur M. Coppola |

11% |

$12,834,624 |

|

88 |

International Business Machines Corp. |

Virginia Rometty |

11% |

$18,595,350 |

|

89 |

MGM Resorts International |

James Joseph Murren |

11% |

$14,579,720 |

|

90 |

Gilead Sciences, Inc. |

John F. Milligan |

11% |

$15,438,459 |

|

91 |

Loews Corp. |

James S. Tisch |

11% |

$6,527,773 |

|

92 |

BlackRock, Inc. |

Laurence D. Fink |

11% |

$27,743,233 |

|

93 |

The TJX Cos., Inc. |

Ernie Herrman |

10% |

$16,880,171 |

|

94 |

Snap-On, Inc. |

Nicholas Pinchuk |

10% |

$10,030,633 |

|

95 |

Stericycle, Inc. |

Charles A. Alutto |

10% |

$3,815,641 |

|

96 |

Gartner, Inc. |

Eugene A. Hall |

10% |

$11,874,230 |

|

97 |

Quest Diagnostics, Inc. |

Stephen H. Rusckowski |

10% |

$10,348,018 |

|

98 |

Raytheon Co. |

Thomas A. Kennedy |

10% |

$24,883,871 |

|

99 |

Eversource Energy |

James J. Judge |

10% |

$15,915,461 |

|

100 |

AT&T, Inc. |

Randall Stephenson |

10% |

$28,720,720 |

|

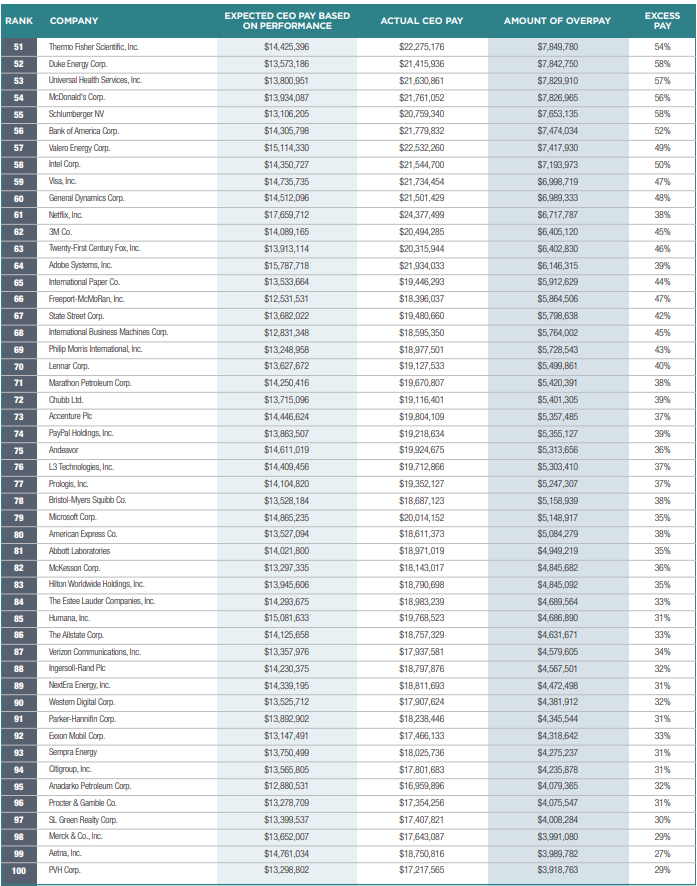

APPENDIX C – HIP INVESTOR REGRESSION ANALYSIS

This table lists Overpaid CEOs, as calculated by the HIP Investor regression analysis, seeking to link CEO pay amount to company financial performance.

Although we, like many other analysts, find very weak links between pay amounts and company financial performance, the usual justification for high executive pay is that they are connected to enhanced profits and above-average capital appreciation for the shareholders who foot the bill. If we grant the assumption that pay should be determined by performance, and then use a basic statistical technique to map actual performance outcomes to predicted levels of pay relative to those outcomes, we can then see how much the CEO pay package exceeded such a prediction. Those with highest excess are ranked in the table below – and constitute this list of Overpaid CEOs of the S&P 500.

Executive pay data series included:

Raw data: Simply looking at every ISS-identified executive's pay package, in each year, as a single data point value – including pay, bonus, stock grants and stock options – to be paired with financial performance for that year.

The series is supplemented using a Thomson Reuters Asset4 data set that captures the single largest pay package for each (company, year) pair. If ISS did not report a CEO for a given pair, and that pair was available in the Asset4 series, the Asset4 data were included. Where ISS identifies multiple co-CEOs who split the job (like Oracle), their pay packages are added together. Once the full set of pay packages is assembled, each (company, year) value is paired with the performance for that year, and this full set is used for the regression.

Each type of executive pay could be reported in any year analyzed from 2007-2018, though not every company was reported for every year.

Financial performance series included:

Return on invested capital (ROIC — cash flow available to pay both debt and equity capital owners, adjusted for tax effects, divided by the total value of that capital). ROIC is sourced from Thomson Reuters WorldScope, which sources data from companies’ annual reports and investor filings.

Total return (capital gains and dividends) on the company’s primary equity. This is calculated from the Thomson Reuters DataStream Return Index series, using trailing periods behind Jun. 30 of the year of the pay package as identified by ISS (or matching the year for the supplementary largest package data from Asset4). Both performance factors were calculated across one-year, three-year, and five-year windows, trailing behind each possible pay year. Thus, data was considered as far back as 2002 (for the five-year window trailing pay data from 2007).

Highlight the titles in any column to sort numerically or alphabetically.

Rank |

Company |

Expected CEO Pay Based on Performance |

Actual CEO Pay |

Amount of Overpay |

Excess Pay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

CSX Corp. | $14,759,495 |

$151,147,286 |

$136,387,791 |

924% |

2 |

Broadcom, Inc. | $16,342,524 |

$103,211,163 |

$86,868,639 |

532% |

3 |

Oracle Corp. | $13,661,713 |

$81,562,244 |

$67,900,531 |

497% |

4 |

CBS Corp. | $13,311,377 |

$69,332,723 |

$56,021,346 |

421% |

5 |

TransDigm Group, Inc. | $14,982,180 |

$61,023,102 |

$46,040,922 |

307% |

6 |

Fleetcor Technologies Inc | $14,483,985 |

$52,643,810 |

$38,159,825 |

263% |

7 |

TripAdvisor, Inc. | $12,914,794 |

$47,933,462 |

$35,018,668 |

271% |

8 |

American International Group, Inc. | $13,393,436 |

$43,086,861 |

$29,693,425 |

222% |

9 |

Discovery, Inc. | $12,555,145 |

$42,247,984 |

$29,692,839 |

236% |

10 |

Mondelez International, Inc. | $13,685,551 |

$42,442,924 |

$28,757,373 |

210% |

11 |

IQVIA Holdings, Inc. | $14,319,285 |

$38,029,517 |

$23,710,232 |

166% |

12 |

The Walt Disney Co. | $13,875,398 |

$36,283,680 |

$22,408,282 |

161% |

13 |

Wynn Resorts Ltd. | $13,616,482 |

$34,522,695 |

$20,906,213 |

154% |

14 |

Electronic Arts, Inc. | $16,054,903 |

$35,728,764 |

$19,673,861 |

123% |

15 |

Allergan Plc | $13,465,352 |

$32,827,626 |

$19,362,274 |

144% |

16 |

Mattel, Inc. | $12,011,101 |

$31,275,289 |

$19,264,188 |

160% |

17 |

Comcast Corp. | $13,819,807 |

$32,520,224 |

$18,700,417 |

135% |

18 |

PepsiCo, Inc. | $13,655,970 |

$31,082,648 |

$17,426,678 |

128% |

19 |

Expedia Group, Inc. | $14,131,894 |

$30,720,457 |

$16,588,563 |

117% |

20 |

Johnson & Johnson | $13,737,591 |

$29,802,564 |

$16,064,973 |

117% |

21 |

AT&T, Inc. | $13,264,807 |

$28,720,720 |

$15,455,913 |

117% |

22 |

Roper Technologies, Inc. | $14,280,367 |

$29,158,675 |

$14,878,308 |

104% |

23 |

Fidelity National Information Services, Inc. | $14,534,851 |

$29,141,610 |

$14,606,759 |

100% |

24 |

Pfizer Inc. | $13,666,781 |

$27,913,775 |

$14,246,994 |

104% |

25 |

JPMorgan Chase & Co. | $14,248,973 |

$28,313,787 |

$14,064,814 |

99% |

26 |

BlackRock, Inc. | $14,208,287 |

$27,743,233 |

$13,534,946 |

95% |

27 |

Prudential Financial, Inc. | $13,601,715 |

$27,111,399 |

$13,509,684 |

99% |

28 |

Booking Holdings, Inc. | $14,392,465 |

$27,774,458 |

$13,381,993 |

93% |

29 |

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | $13,652,915 |

$26,508,058 |

$12,855,143 |

94% |

30 |

Activision Blizzard, Inc. | $15,863,098 |

$28,698,375 |

$12,835,277 |

81% |

31 |

Ventas, Inc. | $13,284,943 |

$25,254,607 |

$11,969,664 |

90% |

32 |