This is the fourth post in a series led by Zach Rausch to figure out the international scope of the youth mental health crisis. (See parts one, two, and three.) We find a surprising pattern within Europe that sheds light on the causes of the crisis.

Here at After Babel, we have systematically documented substantial increases in rates of adolescent depression, anxiety, self-harm, and suicide since 2010. We first showed extensive increases in the U.S., and then across the Anglosphere (U.S., UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand). We showed similar rises in the five Nordic nations (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Iceland). We have also examined changes in suicide rates across nations. In the five Anglosphere countries, rates of adolescent female suicide were relatively steady before 2010.1 Afterward, their rates began to rise, reaching levels higher than those of any previous generation when they were young. Today, we look at all of Europe.

There are still researchers who are skeptical that an international youth mental health crisis broke out in the early 2010s. In a previous post, Zach showed that one reason for this disagreement lies in a widely used international database—the Global Burden of Disease—which tries to estimate rates of mental illness in all countries, including countries that do not collect mental health data. He showed that the GBD systematically underestimates rates of youth mental illness in countries that have robust national mental health data. In fact, it almost entirely misses the spike in countries where a clear spike is found in their own datasets.

A second reason for disagreement comes from researchers (using other databases) who agree that youth mental health may have gotten worse in the countries we have explored, but it did not get worse in many other nations—including places where smartphones proliferated and kids had easy access to social media (one of the core causal factors we believe has driven the crisis).

For example, in a recent post, one researcher argued—citing a study of adolescents from 36 European nations using the Health Behavior in School-Age Children Study (HBSC)—that youth mental health problems “did not increase by anything close to the degree it did in the United States.” Regarding youth suicide trends, the author plotted EU data (27 European countries together) using the Eurostat database and found that “There was no increase in the suicide rate among… all 27 countries of the European Union (EU) taken as a whole…”2

Here is a figure from that post which plots the EU youth suicide trends alongside U.S. trends, showing a small decline in youth suicide in the EU (the black line).

Figure 1. Suicide trends in the U.S. and the European Union. Plotted by Peter Gray, in his Substack post, Multiple Causes of Increase in Teen Suicide Since 2010.

These European trends seem to contradict the core theory that we have been developing at After Babel and in The Anxious Generation: That the adolescent mental health crisis is a result of the transformation of childhood from one that was play-based into one that was phone-based with the peak years of change between 2010 and 2015.3 Are these critiques valid?

In this post, we argue that the skeptics are correct to note that mental health trends vary by nation, but incorrect to conclude that there is little evidence of an international crisis, or that the international trends refute our causal theory. We show that combining trends for girls and boys together hides the fact that there is much stronger evidence of a mental health crisis for girls. We also show that combining all countries of Europe together hides the fact that there is a mental health crisis in the least religious (and most individualistic) countries, which includes, especially, the historically Protestant countries.

When we take these points into consideration, we find that both datasets—the HBSC and Eurostat—reveal the same mental health crisis that we have found in the Anglosphere: worsening adolescent mental health that begins in the early 2010s, especially among girls, and especially among girls in the most individualistic and wealthy nations. But a surprising finding also emerged: Across both datasets, among the most important variables relating to regional variation in youth mental health was the rapid decline in religious life that has happened to various degrees across Europe.

In this post, we will examine European youth mental health data and look at psychological distress trends across 33 different European nations using the HBSC from 2002 through 2018. We will then look at how those distress trends relate to measures of GDP per capita, individualism, and religiosity. We then use the same approach to examine European youth suicide trends in 28 different European nations.

The core argument we make in this post can be summed up like this: Adolescent mental health began to decline across Europe in the early 2010s, with girls and Western European teens hit the hardest. Underlying these regional changes is a story about how adolescents from wealthy, individualistic, and secular nations were less tightly bound into strong communities and therefore more vulnerable to the harms of the new phone-based childhood that emerged in the early 2010s.

(For the sake of length, we do not show all statistical analyses done for this post or the mental health trends for specific European nations. However, you can view these data and graphs in the supplement document for this post, along with Zach’s spreadsheets—HBSC and Eurostat—and his datasets for analysis.)

We began our exploration of European mental health trends using the Health Behavior in School-Age Children Study (HBSC), a multinational survey that has tracked the physical and mental well-being of thousands of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-old adolescents since 2002 from 51 countries.4 To help analyze this data, we teamed up with Thomas Potrebny, from the Western Norway University of Applied Science who has been studying European youth mental health trends for years.

We used a measure of high psychological distress from the HBSC that includes four items that tap different symptoms of psychological distress: feeling low, feeling nervous, feeling irritable, and having sleep difficulties. Respondents rated how often they felt these four symptoms over the last six months (1: Every day, 2: More than once/week; 3, About every week; 4, Every month; 5, Rarely or never). We operationalized high psychological distress as having three or more of the four psychological ailments every day or more than once a week over the last six months.

Using this measure, we computed the average psychological distress score in each country, for girls and for boys separately, in each of the 5 survey years. This gave us two new datasets (one for girls, one for boys), each with 33 rows (one for each country), which facilitated the various cross-country comparisons that we report below.5 We weight each country equally, despite their population differences, because we see each country as a separate case study, each able to contribute information. We always analyze girls and boys separately because we are focused on two questions: Are girls doing worse (or better) since 2010? And are boys doing worse (or better) since 2010? Using these two datasets, we found that the percentage of European 11-15-year-olds with high psychological distress was relatively steady until 2010. And then, as in the Anglo nations, we see an elbow in the curve for the girls.6

Figure 2. Percent of European students who experienced three or more psychological distress symptoms in the last week for at least six months. The percent change compares the average 2002-2010 scores with 2018 scores.7 Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018.8 (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points)9

Knowing that there is likely much variation within Europe, we segmented our analyses using relevant European divisions that could identify variation in adolescent health outcomes: (1) Region (Eastern vs. Western Europe), (2) wealth (defined in this post as GDP per capita), (3) individualism, (4) and religiosity.10

Using the same measure of high psychological distress, we reanalyzed the data breaking nations into Western and Eastern Europe.11 Figure 3 shows that before 2010, rates of distress were generally steady, and higher among Eastern European youth compared to their peers in Western Europe. But beginning in 2010, rates of distress for all teens across Europe began to rise, with the sharpest increase among girls in Western European nations.

Figure 3. Percent of students who experienced three or more psychological distress symptoms in the last week for at least six months by Eastern vs. Western Europe, split by sex. The percent change compares average 2002-2010 scores with 2018 scores. Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points)

Many studies have shown that higher GDP per capita is associated with greater well-being. But many of these studies focus on adults, not on adolescents. What is the impact of wealth on the changes in youth mental health? Are adolescents in wealthier countries buffered, or protected from whatever it is that changed in the early 2010s? Or is it the case that youth in wealthier countries were somehow more exposed, which could explain why it was Western Europe, rather than Eastern Europe, where rates rose fastest.

To answer these questions, we downloaded data on 2014 national GDP per capita from The World Bank (for 33 European nations) and divided those nations into high-wealth nations (top 11 nations) and low-wealth nations (bottom 11 nations).12 We then plotted average psychological distress scores for high- and low-wealth nations from 2002 through 2018 split by sex, which you can see in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Changes in psychological distress categorized by high vs. low GDP per capita, split by sex. The percent change compares the average 2002-2010 scores with 2018 scores. Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points) and The World Bank.

There are two key trends to take note of in the figure above. The first is that high-wealth nations consistently have lower rates of psychological distress compared to lower-wealth nations, consistent with previous findings. The second is that young people in high-wealth nations had higher rates of increase in psychological distress after 2010. The increase was particularly large for girls in the wealthiest nations. Something happened in the early 2010s that had a particularly devastating impact on girls in wealthier countries.13

We also examined a second potential economic moderator: income inequality, which is associated with a variety of social pathologies. Are adolescents from more equal nations mentally healthier? Did low income inequality buffer or protect young people from whatever it is that happened in the early 2010s?

To answer these questions, we used the GINI index, the commonly used measure of economic inequality that provides a score (“GINI coefficient”) for countries around the world. The GINI coefficient ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 indicating perfect equality and 1 indicating perfect inequality. Using the same process as we did for GDP per capita, we divided nations into high- and low-inequality countries (operationalized as the top third and bottom third of European countries on the GINI Index) and then plotted the average distress scores since 2002, split by sex.14 Figure 5 shows that countries with high economic inequality have higher levels of distress than low inequality countries, consistent with the idea that inequality has negative social effects. But just as we saw with GDP per capita, equality did not buffer or constrain the effects of whatever happened in the early 2010s. In fact, mental distress initially rose faster in the more equal nations than it did in the less equal nations, with the largest rise seen among girls in the more equal nations, especially the Nordic nations, along with Slovenia, Belgium, and The Netherlands.

Figure 5. Changes in psychological distress categorized by high vs. low economic inequality of each country, split by sex. Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points) and The World Bank.15

The GDP and GINI findings point to counterintuitive trends: since 2010, adolescent girls from wealthy and economically equal societies have seen the most rapid mental health deterioration. How do we explain these trends? There is little reason to think that increased wealth and decreased inequality are direct causes of a decline in mental health, so we need to look to other key variables that may interact with economic factors to explain this pattern of decline. We examined two cultural variables with many known social ramifications: individualism and religiosity. Based on the analysis we developed in The Anxious Generation, we had reason to believe that Emile Durkheim’s theory of suicide in Europe more than a century ago would still be relevant today: People who are tightly bound into their communities are protected from anomie and from suicide.

One well-identified pattern in cross-cultural research is that individualism and increased wealth tend to go together. The psychological dimension of individualism is central to the cross-cultural work of social psychologist Geert Hofstede, who described it as follows:

“Individualism… is the degree to which people in a society are integrated into groups. On the individualist side we find cultures in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after him/herself and his/her immediate family. On the collectivist side we find cultures in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, often extended families (with uncles, aunts, and grandparents) that continue protecting them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty, and oppose other ingroups.”

Defined this way, individualism is at the heart of more recent work by Michelle Gelfand, who contrasts the social dynamics of “loose” vs. “tight” societies.

In less affluent nations (and communities), individuals tend to focus less on personal identity and desires and are more likely to forgo their desires or projects for the sake of group cohesion (thus being less individualistic). This happens, in part, because individuals from lower-income nations are simply more dependent on their families and immediate community for their own survival (poorer nations also have less government support). This is not the case in wealthier nations. As day-to-day needs are readily met, financial security increases, leisure time increases, and as governments provide more support for individuals, it becomes easier to choose to separate oneself from the larger group that they were born into (thus being more individualistic).

This process of separation between self and group has a number of benefits but also comes with substantial risk. It allows for intellectual, religious, creative, sexual, and spiritual freedom, but it also increases the risk of becoming isolated, disconnected, and spiritually lost (without guidance, norms, support, or purpose). This separation also can impact group-level dynamics, with increasing individualism risking declines in trust and strong social ties within families and communities (which are critical for a play-based childhood).

Although individualism has been understood as a force that generally improves well-being by improving freedom, we believe this may have begun to change in the 2010s, especially among young people. In a rapidly transforming technological world that has amplified the importance of the self while greatly decreasing the time young people spend in face-to-face interaction with other people, individualism may actually exacerbate poor youth mental health.

To examine the relationship between individualism and youth mental health, we used updated versions of Hofstede’s individualism scores (scores range from 0-100, with high scores reflecting higher levels of individualism) for each European nation. We split these nations into “high” and “low” individualism countries (operationalized as the top third and bottom third of European countries on the Hofstede index) and then looked at HBSC psychological distress trends over time (split by sex).16

Figure 6 shows that adolescents from high individualism nations had slightly better mental health than those from lower individualism nations before 2010, but by 2018 that was no longer true.17 Distress rose faster and further in the individualist nations, especially for girls.

Figure 6. Changes in psychological distress by high vs. low individualism of each country, split by sex. Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points) and Hofstede Insights.

There is one more variable for us to consider, one which is often related to wealth and individualism, but is unique in its impact on youth mental health: religiosity.

Religiosity generally trends inversely with wealth and individualism: As wealth and individualism increase, religiosity tends to decrease. This is important because religiosity is among the most consistent and long-standing predictors of positive youth mental health, at least within the United States. (It is also a protective force that helps people maintain psychological health in times of change, stress, and despair. It has also been shown to be protective against internet addiction and internet gaming addiction).18 We thought that it was possible that a key reason why youth in wealthy and individualistic countries are struggling is because those nations have become highly unreligious (thus offering less protection from major societal shocks).

To explore the protective religious hypothesis, we used the Pew Research Center’s index of religiosity (which includes 28 of the European countries included in the HBSC) and broke the HBSC European countries into high and low-religiosity nations (operationalized as the top-third and bottom-third of European countries on the Pew Index of Religiosity).19 We then looked at the changes in psychological distress using the HBSC distress data. Note that Pew’s index defines religiosity as the degree to which individuals within a country: self-assess religion’s importance in their life, how often they attend religious services, their frequency of prayer, and their belief in God.

Figure 7 shows a close resemblance to the figures for individualism and GDP per capita, with pre-2010 rates being generally steady for girls and boys in low religiosity and post-2010 rates spiking upwards.20

Figure 7. Changes in psychological distress by high vs. low religiosity of each country, split by sex. Source: Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points) and and Pew’s Religiosity Index.21

Religiosity is a key variable in understanding changes in youth mental health over the last decade not only because it has protective effects for youth mental health, but also because rates of religiosity have been changing rapidly over the last few decades, and particularly since 2010, within the developed world. As former WHO researcher Colin Mathers explained in a recent essay, "The relatively small changes in the prevalence of religiosity at the global level over the last 40 years conceal quite substantial changes in developed countries and in former Soviet countries, in opposing directions.” Mathers shows that religiosity has actually been increasing since the 1990s in Eastern Europe, while rapidly declining in Western Europe, especially within historically protestant nations (See Figure 8, which shows changes in religiosity in the reformed West (protestant), Old West (catholic), and Orthodox East (Eastern Orthodox)).

Figure 8. The rise of atheism and the decline in religiosity in protestant reformed Europe (left), Catholic Western Europe (middle), and the inverse trends in Eastern Orthodox Europe. Source: Mathers (2021). (Note that a substantial portion of the decline in atheism in Eastern Europe in the 90s was due to the collapse of the USSR and the willingness to report one's true religious feelings. Nonetheless, the continued rise in religiosity since the 2010s cannot be explained by that earlier shift).

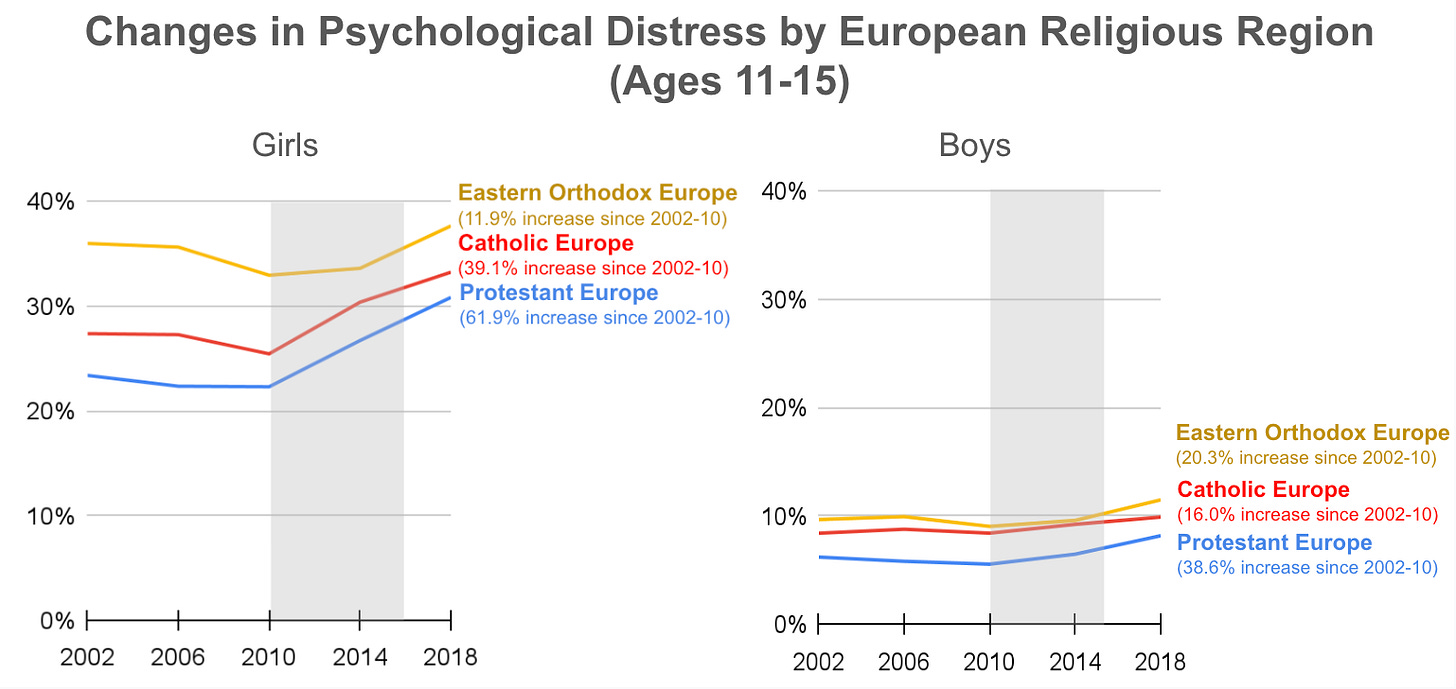

Because of these regional religiosity trends (with decreasing religiosity in the West and increasing Religiosity in the East), we graphed these three different religious regions within Europe with the changes in psychological distress since 2010, as you can see in Figure 9.22

Figure 9. Changes in psychological distress by religious region, split by sex. Rises are most rapid in the Protestant nations. Health Behavior in School-Age Children Survey, 2002-2018. (See Zach’s spreadsheet for data points).

Figure 9 reveals the largest increases in psychological distress were among adolescents in Protestant Europe, for boys as well as girls, compared to the other two religious zones.23 For girls in historically protestant nations, the increase was 62%, which is the largest increase anywhere in this report.

To put all of our findings from the HBSC together, we can say the following: Before 2010, rates of youth psychological distress were lower in nations that were wealthy, or individualistic, or less religious. But something happened in the early 2010s that caused rates of distress to rise faster in those nations than in nations that were less wealthy, more collectivist, or more religious, and this was always more true for girls than for boys.

Now, the HBSC is only one of the two data sources that we discussed at the beginning of the post. What about the second source data—Eurostat—which tracks changes in European youth suicide?

Because this post is already so long, we will go through these findings more quickly.

To analyze suicide trends among 15-19-year-olds, we pulled data from 28 European nations since 2011 using Eurostat, which derives its data from individual EU countries' medical certificates of death. Note that for suicide data broken down by sex, Eurostat only provided rates beginning in 2011, which does not allow us to compare trends before 2010.24 (Also note that this Eurostat dataset did not include data for six of the nations we covered in the HBSC: Ukraine, North Macedonia, Russia, Malta, Luxembourg, and Iceland.)

As we showed in our analysis of the HBSC, it is critical that we break down results by age, sex, and region, and that we consider cultural variation in levels of wealth, individualism, and religiosity. When analysts throw everything into the pot and look at all young people in Europe, they miss important populations that are experiencing a rise in suicide.

We first broke down the EU suicide rate trends by sex. Immediately, we can see that the story is different for boys and girls. Figure 10 shows that when we look at all European countries combined, suicide rates are declining for boys but rising for girls.

Figure 10. Suicide rates in 28 European countries. Rates are slightly rising for girls while declining for boys. Source: Eurostat.The percent change compares 2011-12 rates averaged with 2017 rates. (Spreadsheet).

Let’s break these results down further to see if suicide trends mirror the East-West differences found for psychological distress. Figure 11 shows that for boys, the answer is yes, but for girls, the differences are minimal. (See footnote for country inclusion criteria).25

Figure 11. Suicide trends since 2011, split by sex and European region. (data is merged into 3-year buckets to reduce spikiness and address low yearly base rates). The percent change compares 2011-13 rates with 2017-2019 rates. Source: Eurostat. (Spreadsheet).26

As seen above, suicide rates were declining for Eastern European males through the 2010s, while rates for Western boys generally remained level. The rates of suicide for girls, on the other hand, were generally similar across Eastern and Western Europe throughout the 2010s, with both showing small increases since 2011-13.

As with the HBSC findings, we looked at rate changes across countries divided by GDP per capita, individualism, and religious groupings.27 Figure 12 shows changes in suicide by high- and low-wealth nations.28 Changes in suicide rates were minimal, except that the rate for boys in low wealth nations declined.

Figure 12. Suicide trends since 2011 in High and Low Wealth nations, split by sex. (data is merged into 3-year buckets to reduce spikiness and address low year-to-year base rates). The percent change compares 2011-13 rates with 2017-2019 rates. Source: Eurostat. (Spreadsheet)

Changes in suicide become more apparent when we look at trends by high- and low-individualistic nations. Figure 13 reveals that suicide has been rising for girls from high individualistic nations, and declining for girls in countries that are less individualistic.

Figure 13. Suicide trends since 2011, split by sex and Individualism. (data is merged into 3-year buckets to reduce spikiness and address low yearly base rates). The percent change compares 2011-13 rates with 2017-2019 rates. Source: Eurostat. (Spreadsheet)

Figure 14 shows it was specifically the historically protestant nations where suicide rates among adolescents (especially girls) have risen the most since the early 2010s.

Figure 14. Suicide trends since 2011 in Protestant, Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Europe, split by sex. (data is merged into 3-year buckets to reduce spikiness and address low year-to-year base rates). The percent change compares 2011-13 rates with 2017-2019 rates. Source: Eurostat.29 (Spreadsheet)

In sum, the suicide data tells a similar story to the HBSC: In both cases, rates of European youth suicide rose for girls in the 2010s, especially within individualistic and historically protestant nations.

A final point to note is that the protective religious effects show up within nations too, not just between them. For example, less religious teens in the U.S. have been hit harder by the mental health crisis since 2010 than their more religious peers. Figure 15 shows this clearly. It plots the degree to which U.S. 12th graders—split by gender and religiosity30—agree with the following statements: I feel I do not have much to be proud of, Sometimes I think I am no good at all, I feel that I can't do anything right, and I feel that my life is not very useful.

Figure 15. Self-derogation trends by sex and religiosity, averaging four items from the Monitoring the Future study. The scale runs from 1 (strongly disagree with each statement) to 5 (strongly agree). Source: Monitoring the Future, 2-year buckets. (see Zach’s spreadsheet) Note that the sample sizes were smaller than usual in 2020 and 2021 (and were during COVID).

Before 2010, non-religious teens were only slightly more likely to endorse these self-derogating beliefs. Beginning in the 2010s, American teens became more likely to agree with all four of these statements, but it was the non-religious teens who adopted those beliefs the most. It is important to note that the rise in distress among religious girls in the late 2010s was primarily among religious liberal girls, not religious conservative girls, an important interaction with politics that Jon has discussed in other posts.

In 1897, Emile Durkheim published one of the foundational works of sociology, a book titled Suicide. In the book, he explained that suicide rates should be understood as sociological facts in their own right, rather than just as manifestations of individual psychology. He showed that rates go up and down as a function of social forces that bind groups of individuals together, or that make such binding less likely. Durkheim found that protestant communities had higher suicide rates than did Catholic and Jewish communities, and he argued this was largely due to the fact that individuals in protestant nations were more socially detached, individualized, and free to make their own choices. This left them more vulnerable to anomie, or normlessness.31

Durkheim’s findings can help explain what has happened to the mental health of young people across the Western world since the early 2010s. As young people traded in their flip phones for smartphones and moved their social lives largely away from (already weakened) real-world communities and into chaotic virtual online networks full of loosely connected disembodied users, those who made the move most fully found that their sense of self, community, and meaning-in-life collapsed. Those who were more firmly rooted in mixed-age real-world communities of family, neighborhood, and religion had some protection from this transformation.

We see this pattern across many data sources: In the United States, right around 2012, young people’s feelings of self-loathing, loneliness, and meaninglessness surged upward, especially among the girls who were the least religious and most liberal. And it was the least religious and most liberal girls who embraced the phone-based childhood most rapidly and fully, with 30% of American secular liberal girls spending more than twenty hours a week on social media in 2017, while only 20% of religious conservative girls reported spending that much time. It was generally the wealthy, secular, and individualistic nations that were the first to give children smartphones with social media and high-speed data plans. They were the first countries where young children were able to access the internet anytime, anywhere, with minimal constraints.

But perhaps as important as the quantity of time spent on devices (because many teens from more collectivistic nations now use these devices extensively) is the way that these devices and platforms are being used. In collectivistic nations, smartphones and social media use are more likely to be driven by group-focused motivations such as connecting and building relationships with known friends and family (e.g., spending more time using direct messaging apps). In individualistic nations, smartphones and social media are more likely to be used for self-focused motivations, such as promoting oneself and distinguishing oneself from others, with large quantities of shallower connections (e.g., spending more time on social media platforms). In other words, teens from individualistic nations are more likely to use their smartphones in ways that may lead them to feel more separated and disconnected from others.32

Before the 2010s, most young people from highly individualistic and secular societies were doing well, in terms of mental health, and generally better than those from more collectivist and religious societies. But in the early 2010s, adolescents from these same countries began to wither, while those from less individualistic and more religious societies were less impacted. The NYT columnist Ross Douthat described this transformation of the Western world well when he said,

What looked stable and successful 15 years ago now looks more like a hollowed-out tree standing only because the winds were mild, and waiting for the iPhone to be swung, gleaming, like an ax.

We can think of the 2010s as the period in which teens across the world were suddenly thrust into a world of technologically induced anomie.33 Young people in more collectivistic and religious communities and nations were somewhat more firmly rooted in real-world relationships and were therefore somewhat protected from the meaning-destroying elements of the change. In contrast, in the Anglo countries, the Nordic countries, and in the other formerly Protestant countries of continental Europe, young people were freer to move more of their lives online and onto performative social media platforms, and their mental health suffered more as a result.

The skeptics, whose positions we discussed at the beginning of this post, are correct to point out that youth mental health trends vary around the world. It is simply not the case that every country in Europe is experiencing a youth mental health crisis. But they are incorrect to go a step further and say that this variation refutes the smartphone and social media theory. In fact, variance is exactly what we should expect. We are arguably undergoing the largest and most rapid transformation of childhood in human history, and it is not surprising that the countries that place more importance on real-world groups and obligations have offered more protection for their children.

On self-reporting differences: There are important national and regional differences in the willingness to talk about or report mental health challenges. However, it is important to note that it was the teens from poorer, more religious, and less individualistic nations who generally reported the worst mental health before 2010. The lack of change in these countries since 2010 is unlikely to be because of an unwillingness to report poor mental health outcomes.

As you can see in the supplement for this post, there is extensive variation in well-being and suicide in each nation that cannot be explained by the variables discussed in this post. There are many other factors that contribute to the mental health of young people within and between nations. For example, although the Nordic nations are secular, wealthy, and individualistic, not all show the same suicide rises that we see in other secular, wealthy, and individualistic nations. This may be due to their free and high-quality healthcare systems, high levels of social trust, limited access to lethal means for suicide, and a variety of other institutional, cultural, and social factors.

It is possible that the mental health of adolescents from less wealthy Eastern European nations will worsen in the ways that we have seen across the Anglosphere and Western Europe. It is possible that it is simply taking longer for some countries to fully adopt the phone-based childhood. This is an important question to keep in mind and something to keep track of as we continue to gather data in the coming years.

A key argument in The Anxious Generation is that the loss of the play-based childhood is as important to understanding youth mental health today as is its replacement: the phone-based childhood. In this post, we did not discuss how childhood independence, risky play, and parental overprotection vary across nations. It is likely that societies that still promote childhood independence are doing better than those that do not, even if they have generally high access to smartphones and social media. It is a difficult variable to capture across nations, and we plan to examine this more deeply in future posts.

The variation we saw in this post could also be related to the adoption of the three great untruths, as Jon discussed in a previous post, showing that liberal teens have been hit hardest by the mental health crisis. It is possible that disempowering ideas spread throughout the Western developed world and hit girls from secular, individualistic, and wealthy nations the hardest. There is evidence that young women have become much more liberal across nations since the 2010s. If this hypothesis is true, it would not refute the role of smartphones and social media. Without them, these ideas would not have been able to spread at the rate and scale they did. It is also important to note that social media incentivizes moral outrage, negativity, self-focus, tribalism, and identitarianism—the exact forces behind the three great untruths.

Let us know what you think in the comments. What do you think we are wrong about? What are we missing?