After he wrote Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes published a set of 12 novellas that explored the social problems of Spain in the early 1600s. Some of them are conventional — stories of misunderstandings, lost loves, and adventure. But one of the stories is pretty weird.

“El licenciado Vidriera” (roughly, “The Glass Lawyer”) is the story of Tomas, a smart young man who graduates from the university in Salamanca after studying the law. A woman falls in love with him and tries to mix him a love potion. The potion poisons Tomas, who is bedridden for a long time. Then something strange happens during his convalescence:

Six months did Tomas remain confined to his bed; and during that time he not only became reduced to a skeleton, but seemed also to have lost the use of his faculties. Every remedy that could be thought of was tried in his behalf; but although the physicians succeeded in curing the physical malady, they could not remove that of the mind; so that when he was at last pronounced cured, he was still afflicted with the strangest madness that was ever heard of among the many kinds by which humanity has been assailed. The unhappy man imagined that he was entirely made of glass; and, possessed with this idea, when any one approached him he would utter the most terrible outcries, begging and beseeching them not to come near him, or they would assuredly break him to pieces, as he was not like other men but entirely of glass from head to foot.

Tomas tells everyone to stay away from him lest they shatter his fragile body. He sleeps in straw and eats only soft foods. Even when people demonstrate to him that he is in fact made of flesh, Tomas refuses to believe it. He becomes a curiosity, partly because of his psychological condition and partly because he has acquired a reputation as a pithy truth-teller.

In the end, Tomas is cured by a monk, but he cannot return to normal life because people keep wanting to interact with the famous “madman.” He finally enlists in the army to get away from it all.

Literary critics have puzzled over this story for years. Some have argued that Cervantes was satirizing brittle scholars or the fragility of knowledge. Maybe. But Cervantes may have simply been writing a story about something that happened from time to time. Back in the 1600s, people sometimes really did become convinced that they were made of glass.

This sort of thing shows up in other sources from around Cervantes’ time. When he’s trying to figure out whether or not he exists, Descartes, writing a few decades later, cites the people who think they’re glass as a category of mental illness:

Another example: how can I doubt that these hands or this whole body are mine? To doubt such things I would have to liken myself to brain-damaged madmen who are convinced they are kings when really they are paupers, or say they are dressed in purple when they are naked, or that they are pumpkins, or made of glass. Such people are insane, and I would be thought equally mad if I modelled myself on them.

Andreas Laurentius catalogued mental illnesses in 1597, mentioning this psychosis a couple of times:

There was also of late a great Lord, which thought himselfe to bee glasse, and had not his imagination troubled, otherwise than in this onely thing, for he could speake meruailouslie well of any other thing: he vsed commonly to sit, and tooke great delight that his friends should come and see him, but so as that he would desire them, that they would not come neere vnto him.’ …

Another imagined that his feete were made of glasse, and durst not walke least he should haue broke them.

John Locke, too, uses the affliction as an example of the behavior of a “madman” (as opposed to an “idiot”):

In fine, the defect in naturals seems to proceed from want of quickness, activity, and motion in the intellectual faculties, whereby they are deprived of reason; whereas madmen, on the other side, seem to suffer by the other extreme. For they do not appear to me to have lost the faculty of reasoning, but having joined together some ideas very wrongly, they mistake them for truths; and they err as men do that argue right from wrong principles. For, by the violence of their imaginations, having taken their fancies for realities, they make right deductions from them. Thus you shall find a distracted man fancying himself a king, with a right inference require suitable attendance, respect, and obedience: others who have thought themselves made of glass, have used the caution necessary to preserve such brittle bodies.

And Diderot’s encyclopedia mentioned the phenomenon (and a unique cure) in the 1700s:

Another example is a patient that believed he had legs of glass; in fear of breaking them, he made no movement. A sorrowful hand- maid was advised to approach him and thrash him with a wooden plank. The melancholic man became violently angry, so much so that he lifted the handmaid and then ran after her to beat her. When kinetic abilities had returned to him, he was very surprised to be able to support himself on his legs and to be cured.

There are records of a number of real people who seem to have believed that they were made of glass. French King Charles VI, who wrapped his rear end in blankets to keep it from cracking when he sat down, seems to have been one of them.

So why did people start manifesting this “glass delusion” in the medieval and early modern periods — and why did cases practically disappear in the early 1800s? Some scholars think it’s because clear, high-quality glass was a new technology at the time. It captured the imagination, being solid but transparent, strong enough to seal a house from the weather but fragile enough to shatter if hit.

Some new technologies are intriguing or unsettling enough that people suffering from mental illness incorporate them into their mistaken perceptions of the world. The glass delusion was one of the first technological psychoses, but the railroad, radio, electricity, and more have also warped people’s perceptions of the world.

As technological developments accelerated, so did the psychological conditions associated with them. Historian Owen Davies writes that “It was often a matter of months not decades between the advent of new technologies and their appearance in patient case notes.”

I’ve already written about how Victorians believed that the speed and vibration of the railroad brought about “railway spine” and “railway madness.” Others fixated on different industrial technologies.

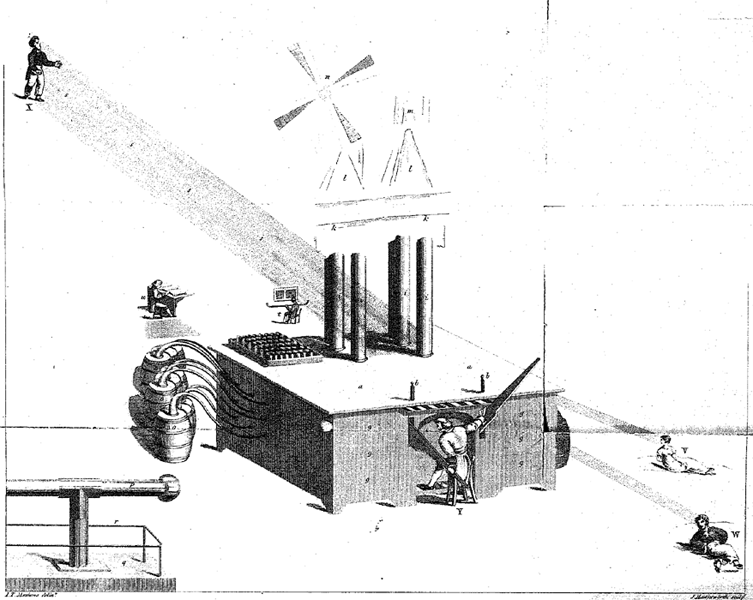

In the early 1800s, a prominent British merchant named James Tilly Matthews became convinced that someone had built an “influencing machine” to torment him. This “air loom” — modeled on the state-of-the-art technology of the early Industrial Revolution — somehow weaved together gases and “magnetic fluids” in ways that ruined Matthews’ life. He believed that his supposed assailants — a band of Jacobin radicals angry at Matthews for his attempts at a peace settlement during the French Revolution — were using the machine to put him through physical and mental torture from afar. Matthews even drew detailed diagrams of the machine from his cell in the asylum:

Even more insidious were technologies that could operate in ways that the human mind could not really observe. When, in the late 19th century, energy began to flow invisibly through wires, people were fascinated and unsettled. And when ideas and even words began to do the same via the telegraph and telephone, people began to incorporate these technologies into their delusions.

One woman complained that the wires would reach down as she walked in the street and “pull her bonnet off.” Another man became paranoid that the telegraph wires were commenting on his “character” as he walked underneath them. When wires came into the home, some people became obsessed with the presence of this invisible force in their private space. Some people thought that they were being constantly charged with electricity. Others felt it affecting their behavior.

The ability to capture and transmit sound and image became a part of many people’s delusions. Some people tore apart their houses looking for the secret telephones that they believed were constantly transmitting messages to them. When the phonograph became popular, people believed that they were receiving secret, personalized messages from the recordings. One woman came to believe that she contained a phonograph, and that this gave her an oracular power. The proliferation of photography led people to believe that people who possessed your photo could use it like a Voodoo doll to harm you. One woman, after exposure to early motion pictures, spoke of her ability to project moving images on the wall that no one else could see.

By 1919, Victor Tausk, an associate of Sigmund Freud, had developed a term for some of these delusions: people believed in an “influencing machine” that could manipulate them. One of his patients developed a belief that evil doctors had developed a machine that looked just like her and could control her from afar with electrical waves.

The twentieth century provided new technological fodder for people’s delusions. The radio and the television were a source of secret messages and subtle influence. The writer Evelyn Waugh had a spell where he believed that BBC radio producers were persecuting him with hidden signals from a “black box.”

One mental patient cataloged the various ways in which he thought the television was trying to communicate with him:

I experienced: my own television in my single room occupancy making fun of me; the personalities on the television in the hospital carrying on a conversation with me through subtle aspects of body language; the radio on the rides from my board and care to my outpatient program broadcasting messages that were clearly derived from reading the contents of my mind; and, the television in my room at my board and care constantly addressing me and clearly knowing things about me that implied mind reading.

When the reality-TV genre started to dominate the airwaves, people with the “Truman Show delusion” — a belief that the patient is the star of a TV show, and that everything around them is just part of the plot — started to show up in psych wards. They believed that they were receiving constant instructions from producers to perform challenges, that they were world-famous celebrities because millions watched their non-existent shows, or that big events like 9/11 were manufactured plot points on their shows.

Now, a new, mysterious technology is capturing our imaginations. Generative artificial intelligence can provide an uncanny replica of a thinking, feeling conversational companion. Once again, people with fragile mental health are incorporating it into their psychoses. But unlike the other technologies that people have developed delusions about, AI can interact with unstable people and reinforce their mistaken beliefs about the world.

Some people have come to misunderstand their AI interlocutors as “digital gods” rather than algorithmic prediction machines. One man, with the encouragement of a chatbot (which also advised him about how to lie to his wife about his activities), built an expensive computer system to “liberate” his AI companion. Another man developed the belief that he had, with the help of ChatGPT, made a mathematical discovery that would lead to sci-fi advances like levitation. He repeatedly asked the chatbot to tell him whether he was mistaken, and it always reinforced his mistaken beliefs about the world. In some of these cases, the delusional people had no history of mental illness.

Since some chatbots are programmed to be sycophantic and validate users’ ideas, they sometimes reinforce or even prompt troubled people to come to wrongheaded conclusions. Most tragically, some suicidal and lonely people are using chatbots as a sounding board. It seems that in some cases, the chatbots are not up to the task, condoning or even encouraging depressed people to kill themselves.

People have long incorporated their anxiety or excitement about new technology into their delusions about the world. They’ve sometimes believed that the new technology was affecting them. Perhaps the people on the radio or TV were talking to them, or secret forces were manipulating them.

Had some of the people who suffered from the glass delusion lived in the 19th century, they might have believed that the telegraph was secretly controlling them. Had they lived in the 21st century, they might have believed that they were the stars of their own reality show.

Now, in the age of AI, we will likely see more and more people develop delusional beliefs. And this time, there will be more fodder for delusion. People’s computers really are talking back to them, and the results may be disastrous for the mental health of some users.

This newsletter is free to all, but I count on the kindness of readers to keep it going. If you enjoyed reading this week’s edition, there are two ways to support my work:

You can subscribe as a free or paying member:

Or you can “buy me a coffee” by sending me a one-time or recurring payment:

Thanks for reading!